Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Moropus

View on Wikipedia

| Moropus Temporal range: Early-Middle Miocene,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Moropus elatus skeleton at the National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC | |

| |

| Reconstruction of the head of M. elatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | †Chalicotheriidae |

| Subfamily: | †Schizotheriinae |

| Genus: | †Moropus Marsh, 1877 |

| Type species | |

| Moropus distans Marsh, 1877

| |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Synonyms of M. elatus

| |

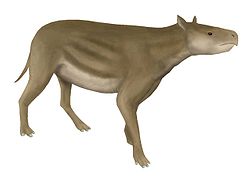

Moropus (meaning "slow foot")[2] is an extinct genus of large perissodactyl mammal in the chalicothere family. They were endemic to North America during the Miocene from ~20.4–13.6 Mya, existing for approximately 6.8 million years. Moropus belonged to the schizotheriine subfamily of chalicotheres, and has the best fossil record of any member of this group; numbers of individuals, including complete skeletons, have been found. The type species of Moropus, M. distans, was named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1877, alongside two other species, M. elatus and M. senex. Three more species have been named since. Others have been named, but have either been invalidated for one reason or another, or reclassified to other genera.

Among the largest chalicotheres, some specimens of Moropus stood 2.4 m (8 ft) at the shoulder. One specimen had an estimated body mass of 1,179 kg (2,599 lb). Its dental anatomy was similar to ruminants, suggesting a similar method of cropping vegetation. Retracted nasal bones suggest a long upper lip, and a wide gap between the lower incisors and cheek teeth, called a diastema, would provide room for a long tongue to extend from the mouth at an angle. Together, the upper lip and tongue may have been used to pull down vegetation. Though not as adept at bipedalism as the related Chalicotherium, it may nonetheless have reared up on two legs to browse on vegetation, using its claws to hook into the bark of a tree or using them to pull down leaves that would otherwise have been unreachable. Moropus may have been sexually dimorphic, with the males being larger than the females.

Taxonomy

[edit]Early history

[edit]The first of the remains currently assigned to Moropus was a partial right maxilla (YPM 10030), uncovered at some point prior to 1873. In that year, the specimen was described YPM 10030, initially mistakenly attributed to Lophiodon.[3] After its discovery, multiple more complete specimens were discovered in the Miocene strata of the John Day Fossil Beds of Oregon.[4] In 1877, Othniel Charles Marsh formally described the specimens, assigning to them the genus name Moropus. The type species of Moropus, M. distans, was based only on fragments of the hind foot.[4][5] Two other species, M. elatus and M. senex, were also described. At first, Marsh believed that Moropus belonged to the order Edentata, which historically included any mammal that lacked incisor teeth. Though he noted affinities with the African Ancylotherium, he opted to erect a new family, Moropodidae, to exclusively include Moropus.[5] In 1908, geologist and palaeontologist Erwin Hinckley Barbour noted that Moropus had occasionally been treated as a form intermediate between edendates and ungulates, though affirmed that it was definitely a true ungulate.[6]

In 1913, Olof August Peterson named a new species of Moropus, M. hollandi, from limb elements recovered in 1901, at first mistakenly assigned to M. elatus.[7] In a 1913 monograph on chalicothere taxonomy, Moropus in particular, Peterson and William Jacob Holland recognised two additional species, M. matthewi and M. merriami, and reassigned Moropus to Chalicotheriidae.[4]

Invalid or reassigned species

[edit]In 1892, Barbour came into possession of a partial mammal skeleton from the Agate Fossil Beds National Monument.[8] He assigned the specimen to Moropus, and named a new species, M. cooki (after Harold Cook, who discovered it) based on it. However, Peterson and Holland considered M. cooki a junior synonym of M. elatus.[4] In 1907, Holland named M. petersoni, also from the Agate Fossil Beds, after Peterson.[9] Later, in 1975, Margery Chalifoux Coombs suggested that M. petersoni was instead the same taxon as M. elatus, and that its differences could be explained through sexual dimorphism .[10] In 1935, Soviet palaeontologist K.K. Flerov named an Asian species of Moropus, "M." betpakdalensis from Kazakhstan.[11] This taxon has since been reassigned to a genus of its own, Borissiakia.[12] Another purported Asian Moropus, "M." huangheensis, has also been reassigned to Borissiakia.[13]

Taxonomy

[edit]Chalicotheres are part of the order Perissodactyla, which includes modern equines, rhinoceroses, and tapirs, as well as extinct groups like brontotheres.[14][15] As the early evolution of perissodactyls is still unresolved, their closest relatives among other perissodactyl groups is obscure.[15] They are generally placed as part of the clade Ancylopoda alongside their close relatives Lophiodontidae. Many studies considered them as closer to Ceratomorpha (which includes tapirs and rhinoceroses) than Equoidea.[16][17] A 2004 cladistic study alternatively recovered Ancylopoda as sister to all modern perissodactyls (which includes Equoidea and Ceratomorpha), with the brontotheres basal to both.[18]

In their 1914 monograph on chalicotheres, Holland and Peterson listed three subfamilies: Moropodinae (Ancylotherium, Moropus, and Nestoritherium), Macrotheriinae (including Chalicotherium, Circotherium, and Macrotherium) and Schizotheriinae (Pernatherium and Schizotherium).[4] Macrotheriinae was subsequently synonymised with the existing Chalicotheriinae. Palaeontologist Arthur Smith Woodward, in 1925, concurred with the system used by Holland and Peterson, and only altered the placements of a few genera.[19] William Diller Matthew instead split chalicotheres into just two subfamilies, Chalicotheriinae and Eomoropinae. The former was divided into two clades based on whether their teeth were brachydont (short-crowned) or hypsodont (high-crowned): Moropus fell into the latter category.[20] In 1935, Edwin H. Colbert retained this system, though divided Chalicotheriinae into the tribes Chalicotheriini and Schizotheriini.[19] Currently, they are both treated as tribes,[12] and eomoropids have been removed from Chalicotheriidae entirely.[21][22] Moropus is currently classified under Schizotheriinae.[23]

Description

[edit]

Some species of Moropus, such as M. elatus, were among the largest chalicotheres,[5] standing about 2.4 m (8 ft) tall at the shoulder and with a body weight around the size of a large rhinoceros.[4] One Moropus specimen has an estimated body mass of 1,179 kg (2,599 lb).[24][25] Smaller specimens have been described as being about the size of a tapir.[4][26]

Skull

[edit]Moropus' skull was fairly small compared to its body.[27] It was narrow, and bore high nasal bones. The snout had a spoon-shaped tip, a characteristic common to selective browsers. It suggests the presence of mobile lips and possibly a long tongue.[27] William Berryman Scott suggested that the tongue may have been used in conjunction with the upper lip to pull down branches.[28] The lower incisors protruded forwards, and the premaxilla is toothless, similar to in modern ruminants. This would have formed a cropping mechanism for processing vegetation. There was a diastema (gap) separating the incisors from the cheek teeth, which would have allowed the tongue to extrude from the mouth.[27] The maxilla was similar to that of modern horses (Equus).[4] Some specimens (or species) Moropus did not have a sagittal crest,[6] while others did, even as juveniles.[4]

Dentition

[edit]Moropus had incisors only on the lower jaw.[29] The cheek teeth (the premolars and molars) were robust, covered in thick enamel, and strongly rooted. The first upper premolar is absent, like other chalicotheres. The second upper premolar was triangular, with the protocone and tritocone (cusps) having fused into a single structure, mostly comprising the former. The third upper premolar is more quadrate in shape, and has one tubercle rather than two. The fourth upper premolar is slightly larger but otherwise very similar.[4] The lower incisors, of which there were three on each side,[4] are procumbent (protruding), spatulate, and were separated from the cheek teeth by a long diastema.[29] The first upper molar is very enlarged, the second is one-fifth longer, and the third is only slightly larger. All three are roughly the same in terms of overall structure. The second lower premolar is highly reduced. Third is molariform (molar-like), in a similar fashion to the brontothere Megacerops. The first lower molar is considerably wider than the fourth lower premolar, though they are otherwise quite similar, with the exception that the hypoconid is more well-developed and the cingulum is less so. The second lower molar is longer, and has a more prominent cingulum. The third lower molar lacks its third lobe, similar to other chalicotheres.[4]

Postcranial skeleton

[edit]Moropus' neck was somewhat like that of a modern horse, albeit considerably stockier.[4] All of Moropus' cervical (neck) vertebrae were somewhat elongated, and the neck was long enough that, when drinking, Moropus would have to splay its forelimbs to reach the ground level, as in modern giraffes. This, and the fact that the dorsal musculature of the neck appears to have been stronger than the ventral musculature, suggest that Moropus held its neck obliquely upright.[27] As in other chalicotheres, Moropus differed from typical ungulates in having large claws, rather than hooves, on the feet. Three large, highly compressed claws were present on each of the front feet, supported inside by fissured bony phalanges. As with all schizotheriines, the articulation of the phalangeal (finger) bones shows that Moropus could retract its claws enough to walk smoothly with the front feet in a normal digitigrade stance, lifting the claws by hyperextension. Moropus was likely more heavily quadrupedal than Chalicotherium. However, while not as extreme as in Chalicotherium, Moropus' pelvis still bore some adaptations for bipedal stance, such as a long ischium, and changes in the structure of the hindfoot (i.e. the shortening and widening of the astragalus) to increase its weight-bearing capabilities without sacrificing limb length.[27]

Palaeobiology

[edit]

Feeding and diet

[edit]The spoon-shaped snout tip of Moropus suggests that it was a browser.[27] It was suggested by William Diller Matthew that Moropus used its claws to dig for buried plant matter and water sources,[20] though as it did not live in an arid environment, this is unlikely.[27] Russian palaeontologist Alexey Borissiak suggested, based on Borissiakia from Kazakhstan, that schizotheriines may have fed bipedally, wedging their front claws into tree bark for support. The middle claw could be driven directly into the bark, while the first and third could be freely moved as necessary.[30] In 1943, Swiss palaeontologist Samuel Schaub suggested that the related Ancylotherium used its forelimbs to pull down vegetation,[31] much as in chalicotheriines.[27]

Sexual dimorphism

[edit]There has been some debate over whether Moropus was sexually dimorphic. The matter was discussed by Olof August Peterson and William Jacob Holland in their monograph, in reference to two different mature size groups that had been noted. The larger one was M. elatus, and the other was, at the time, considered M. petersoni. Larger individuals possessed small sagittal crests, whereas smaller individuals did not (and instead retained independent supraorbital ridges), though noted this could be due to sexual dimorphism. They supposed that, if they were females, the smaller specimens would have a larger pelvic cavity with larger foramina for blood supply, which is not observed. Based on the relative subtetly of these differences, which did not, to them, indicate sexual dimorphism, the smaller morph was decided to probably be separate, and Moropus petersoni was retained as a taxon.[4] However, Margery Chalifoux Coombs suggested that there was, in reality, no reason to assume that sexual dimorphism was absent, and opted to sink M. petersoni into M. elatus. She suggested that "M. petersoni", being smaller, may have represented the female of M. elatus. Further, she noted that there were cases of possible sexual dimorphism throughout Chalicotheriidae, and that there would be a strong precedent for it.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ "Moropus in the Paleobiology Database". Fossilworks. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Carlton, Robert L. (2018), Carlton, Robert L. (ed.), "M", A Concise Dictionary of Paleontology, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 165–184, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73055-4_13, ISBN 978-3-319-73055-4, retrieved 2025-01-11

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Leidy, Joseph (1873). Contributions to the extinct vertebrate fauna of the western territories. Washington: Govt. Print. Off.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Holland, William Jacob; Peterson, Olof August (1913). "The osteology of the Chalicotheroidea with special reference to a mounted skeleton of Moropus elatus Marsh, now installed in the Carnegie museum". Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum. 3 (2): 189––406. doi:10.5962/p.211102. hdl:2027/hvd.32044066256439.

- ^ a b c Marsh, Othniel Charles (1877). "Notice of Some New Vertebrate Fossils" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 81 (81): 249–256. Bibcode:1877AmJS...14..249M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-14.81.249.

- ^ a b Barbour, Erwin (1908-01-01). "The Skull of Moropus". Conservation and Survey Division.

- ^ Peterson, O. A. (1913-11-07). "A New Species of Moropus ( M. hollandi ) from the Base of the Middle Miocene of Western Nebraska". Science. 38 (984): 673–680. doi:10.1126/science.38.984.673.a. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17732680.

- ^ Cockerell, T. D. A. (1923). "Fossil Mammals at the Colorado Museum of Natural History". The Scientific Monthly. 17 (3): 271–277. ISSN 0096-3771. JSTOR 3693057.

- ^ Holland, W. J. (1908). "A New Species of the Genus Moropus". Science. 28 (727): 809–810. Bibcode:1908Sci....28..809H. doi:10.1126/science.28.727.809. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1634948. PMID 17780444.

- ^ a b Coombs, Margery Chalifoux (1975). "Sexual Dimorphism in Chalicotheres (Mammalia, Perissodactyla)". Systematic Zoology. 24 (1): 55–62. doi:10.2307/2412697. ISSN 0039-7989. JSTOR 2412697.

- ^ Flerov, K. K. (1938). "Remains of Ungulata from Betpak–dala". C. R. Acad. Sci. 21: 94–96.

- ^ a b Butler, Percy Milton (1965). "Fossil mammals of Africa No. 18: East African Miocene and Pleistocene chalicotheres". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Geology. 10: 163–237.

- ^ Li, Zhaoyu; Mörs, Thomas; Zhang, Yunxiang; Xie, Kun; Li, Yongxiang (2022-12-01). "New Material of Schizotheriine Chalicothere (Perissodactyla, Chalicotheriidae) from the Xianshuihe Formation (Early Miocene) of Lanzhou Basin, Northwest China". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 29 (4): 877–889. doi:10.1007/s10914-022-09619-3. ISSN 1573-7055.

- ^ Savage, RJG; Long, MR (1986). Mammal Evolution: an illustrated guide. New York: Facts on File. pp. 198–199. ISBN 0-8160-1194-X.

- ^ a b Holbrook, Luke T.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Emry, Robert J. (2004). "Skulls of the Eocene Perissodactyls (Mammalia) "Homogalax" and "Isectolophus"". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (4): 951–956. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0951:SOTEPM]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 4524789. S2CID 86289060.

- ^ Froehlich, David J. (1999). "Phylogenetic Systematics of Basal Perissodactyls". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19 (1): 140–159. Bibcode:1999JVPal..19..140F. doi:10.1080/02724634.1999.10011129. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 4523976.

- ^ Tsoukala, Evangelia (2022), Vlachos, Evangelos (ed.), "The Fossil Record of Chalicotheres (Mammalia: Perissodactyla: Chalicotheriidae) in Greece", Fossil Vertebrates of Greece Vol. 2, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 501–517, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-68442-6_15, ISBN 978-3-030-68441-9, retrieved 2024-08-22

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Hooker, J. J.; Dashzeveg, D. (2004). "The origin of chalicotheres (Perissodactyla, Mammalia)". Palaeontology. 47 (6): 1363–1386. Bibcode:2004Palgy..47.1363H. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00421.x. ISSN 1475-4983. S2CID 83720739.

- ^ a b Colbert, Edwin Harris; Brown, Barnum (1935). "Distributional and phylogenetic studies on Indian fossil mammals. 3, A classification of the Chalicotherioidea". American Museum Novitates (798).

- ^ a b Matthew, William Diller (1929). "Critical Observations Upon Siwalik Mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History: 516–524.

- ^ Holbrook, L (1999). "The Phylogeny and Classification of Tapiromorph Perissodactyls (Mammalia)" (PDF). Cladistics. 15 (3): 331–350. doi:10.1006/clad.1999.0107.

- ^ Missiaen, Pieter; Gingerich, Philip D. (2012). "New Early Eocene Tapiromorph Perissodactyls from the Ghazij Formation of Pakistan, with Implications for Mammalian Biochronology in Asia". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 57 (1): 21–34. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0093. hdl:1854/LU-3178691. ISSN 0567-7920.

- ^ Coombs, Margery C.; Hunt, Robert M.; Stepleton, Ellen; Albright, L. Barry; Fremd, Theodore J. (2001-08-22). "Stratigraphy, chronology, biogeography, and taxonomy of early Miocene small chalicotheres in North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (3): 607–620. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0607:SCBATO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Etienne, Cyril; Mallet, Christophe; Cornette, Raphaël; Houssaye, Alexandra (2020-03-28). "Influence of mass on tarsus shape variation: a morphometrical investigation among Rhinocerotidae (Mammalia: Perissodactyla)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 129 (4): 950–974. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blaa005. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ Damuth, John, ed. (2005). Body size in mammalian paleobiology: estimation and biological implications (1. paperb. version ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01933-0.

- ^ Marsh, Othniel Charles (1878). Introduction and succession of vertebrate life in America. An address delivered before the American association for the advancement of science, at Nashville, Tenn., August 30, 1877. New Haven, Conn: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, printers.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Coombs, Margery Chalifoux (1983). "Large Mammalian Clawed Herbivores: A Comparative Study". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 73 (7): 1–96. doi:10.2307/3137420. JSTOR 3137420.

- ^ Scott, William Berryman (1913). A history of land mammals in the Western Hemisphere; illustrated with 32 plates and more than 100 drawings. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ a b Coombs, Margery Chalifoux (1978). "A Premaxilla of Moropus elatus Marsh, and Evolution of Chalicotherioid Anterior Dentition". Journal of Paleontology. 52 (1): 118–121. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1303796.

- ^ Borissiak, Alexey A. (1945). "The chalicotheres as a biological type" (PDF). Am. J. Sci. 243 (12): 667–679. Bibcode:1945AmJS..243..667B. doi:10.2475/ajs.243.12.667. PMID 21004238.

- ^ Schaub, Samuel (1943). "Die Vorderextremitat von Ancylotherium pentelicum Gaudry und Lartet". Schweizerischen Palaeont. Abhandl. 64: 1–36.