Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nantwich

View on Wikipedia

Nantwich (/ˈnæntwɪtʃ/ NAN-twitch) is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It has among the highest concentrations of listed buildings in England, with notably good examples of Tudor and Georgian architecture. At the 2021 census, the parish had a population of 14,045 and the built up area had a population of 18,740.

Key Information

History

[edit]The origins of the settlement date to Roman times,[3] when salt from Nantwich was used by the Roman garrisons at Chester (Deva Victrix) and Stoke-on-Trent as a preservative and a condiment. Salt has been used in the production of Cheshire cheese and in the tanning industry, both products of the dairy industry based in the Cheshire Plain around the town. Nant comes from the Welsh for brook or stream. Wich and wych are names used to denote brine springs or wells. In 1194 there is a reference to the town as being called Nametwihc, which would indicate it was once the site of a pre-Roman Celtic nemeton or sacred grove.[4]

In the Domesday Book of 1086, Nantwich is recorded as having eight salt houses. It had a castle and was the capital of a barony of the earls of Chester, and of one of the seven hundreds of medieval Cheshire. Nantwich is one of the few places in Cheshire to be marked on the Gough Map, which dates from 1355 to 1366.[5] It was first recorded as an urban area at the time of the Norman Conquest, when the Normans burnt the town to the ground,[6] leaving only one building standing.

Nantwich Castle was built at the crossing of the Weaver before 1180, probably near where the Crown Inn now stands. Although nothing remains of the castle above ground, it affected the town's layout.[7][8] During the medieval period, Nantwich was the most important salt town and probably the second most important settlement in the county after Chester.[9][10] By the 14th century, it was holding a weekly cattle market at the end of what is now Beam Street, and it was also important for its tanning industry centred in Barker Street.[11]

A fire in December 1583 destroyed most of the town to the east of the Weaver.[12][13] Elizabeth I contributed funds to the town's rebuilding and made an England-wide appeal for support for the rebuilding fund which thereby received funds from many successful medieval towns, including Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk. The rebuilding occurred rapidly and followed the plan of the destroyed town.[14] Beam Street was so renamed to reflect the fact that timber (including wood from Delamere Forest) to rebuild the town was transported along it. A plaque marking the 400th anniversary of the fire and of Nantwich's rebuilding was unveiled by the Duke of Gloucester on 20 September 1984.[15]

From the time of the Henrician Reformation, the town had trouble finding good Protestant preachers. An example of the problem was Stephen Jerome, a puritanical preacher, who in 1625 nonetheless tried to rape one of his maidservants, Margaret Knowsley. Rumours of this spread across the town, eventually leading to Knowsley's imprisonment and public shaming in 1627. A few years later, Jerome went to Ireland to continue his preaching career.[16]

During the English Civil War Nantwich declared for Parliament and was besieged several times by Royalist forces. A final six-week siege was lifted after a Parliamentary victory in the Battle of Nantwich on 26 January 1644. This has been re-enacted as "Holly Holy Day" on every anniversary since 1973 by Sealed Knot, an educational charity. The name is taken from commemorative sprigs of holly worn by townsfolk in caps or on clothing in the years after the battle.[17]

The salt industry peaked in the mid-16th century, with about 400 salt houses in 1530, but had almost died out by the end of the 18th century; the last salt house closed in the mid-19th century.[18][19][20] Nikolaus Pevsner considered the salt-industry decline to have been critical in preserving the town's historic buildings.[18] The last tannery closed in 1974. The town's location on the London–Chester road meant that Nantwich began to serve the needs of travellers in medieval times.[9][21] This trade declined in the 19th century with the opening of Telford's road from London to Holyhead, which offered a faster route to Wales, and later with the Grand Junction Railway, which bypassed the town.[19]

Nantwich Mill

[edit]The presence of a watermill south of Nantwich Bridge was noted in 1228[22] and again about 1363,[23] through the cutting of a mill race or leat and creation of an upstream weir. The resulting Mill Island was ascribed to the 16th century,[22][23] possibly after the original mill was destroyed in the 1583 Great Fire of Nantwich.

In the mid-17th century, the mill was acquired by local landowners, the Cholmondeleys, who retained it until the 1840s.[22] Originally a corn mill, it became a cotton mill (Bott's Mill) from 1789 to 1874,[22][23][24] but reverted to being a corn mill and was recorded as such on the Ordnance Survey First Edition map of Nantwich in 1876.[23] A turbine was installed in about 1890 to replace the water wheel.[22]

The mill was demolished in the 1970s after a fire[22] and then landscaped, with further stabilisation of the mill foundations in 2008.[25] Today it forms part of a riverside park area. Proposals, so far unfollowed, have been made for small-scale hydropower generation using the mill race.[26][27] Nantwich Mill Hydro Generation Ltd was incorporated in April 2009, but dormant in December 2016.[28]

Brine baths

[edit]Nantwich's brine springs were used for spa or hydrotherapy purposes at two locations: the central Snow Hill swimming pool inaugurated in 1883,[23][29] where the open-air brine pool is still in use,[30] and the Brine Baths Hotel, standing in 70 acres (28 ha) of parkland south of the town from the 1890s to the mid-20th century.[31] The hotel was originally a mansion, Shrewbridge Hall,[23] built for Michael Bott (owner of Nantwich Mill) in 1828. It was bought by Nantwich Brine and Medicinal Baths Company in 1883, extended and opened as a hotel in 1893,[31] with "a well-appointed suite of brine and medicinal baths,"[32] – also described as the "strongest saline baths in the world".[31] These were used to treat patients with ailments that included gout, rheumatism, sciatica and neuritis, using two suites of baths.[33][34]

The hotel's grounds included gardens, tennis courts, a nine-hole golf course and a bowling green. The last survives today as the Nantwich Park Road Bowling Club founded in 1906.[35]

The hotel served as an auxiliary hospital during the First World War.[36] In the Second World War it became an army base and then accommodated WAAF personnel. It closed as a hotel in 1947 and in 1948 became a convalescent home for miners. In 1952 that closed and the building was unsuccessfully put up for sale and demolished in 1959.[32] The grounds were later developed for housing – the Brine Baths Estate[31] – and schools (Brine Leas School and Weaver Primary School).

Governance

[edit]

There are two tiers of local government covering Nantwich, at civil parish (town) and unitary authority level: Nantwich Town Council and Cheshire East Council. The town council is based at the Civic Hall on Market Street.[37] Parts of the built up area extend into neighbouring parishes, notably Stapeley and District to the south-east.[38]

For national elections, the town is mostly in the Crewe and Nantwich constituency, though some western parts are in the Chester South and Eddisbury constituency.[38] A Nantwich constituency covering the town and surrounding rural areas existed between 1955 and 1983.

Administrative history

[edit]Nantwich was anciently part of the parish of Acton.[39] Nantwich had a chapel of ease from at least the 12th century, which was rebuilt as the current St Mary's Church in the 14th century.[40] It is unclear exactly when Nantwich became a separate parish from Acton, although it was treated as a separate parish by 1677.[41]

The parish of Nantwich contained the townships of Alvaston, Leighton and Woolstanwood, as well as a Nantwich township covering the town itself and adjoining areas, plus western fringes of the township of Willaston.[42][43] From the 17th century onwards, parishes were gradually given various civil functions under the poor laws, in addition to their original ecclesiastical functions. In some cases, including Nantwich, the civil functions were exercised by each township separately rather than the parish as a whole. In 1866, the legal definition of 'parish' was changed to be the areas used for administering the poor laws, and so the townships also became civil parishes.[44]

In 1850, the Nantwich township was also made a local board district, administered by an elected local board. Such districts were reconstituted as urban districts under the Local Government Act 1894.[45] The urban district was enlarged in 1936, taking in areas from several neighbouring parishes.[46]

Nantwich Urban District Council moved its offices to Brookfield House on Shrewbridge Road in 1949.[47] It also built the Civic Hall on Market Street to serve as a public hall and entertainment venue, opening in 1951.[48][49] The town's previous main public hall had been the privately owned Town Hall beside Nantwich Bridge on the High Street, which was built in 1868 and closed by 1945; it was demolished in 1972.[50]

Nantwich Urban District was abolished in 1974 under the Local Government Act 1972. The area became part of the larger borough of Crewe and Nantwich, also covering the nearby town of Crewe and surrounding rural areas. The government originally proposed calling the new borough Crewe, but the shadow authority elected in 1973 to oversee the transition changed the name to 'Crewe and Nantwich' before the new arrangements came into effect.[51][52][53] A successor parish covering the area of the former Nantwich Urban District was created at the same time, with its parish council taking the name Nantwich Town Council.[54]

In 2009, Cheshire East Council was created, taking over the functions of Crewe and Nantwich Borough Council and Cheshire County Council, which were both abolished.[55]

Places of interest

[edit]

Nantwich has one of the county's largest collections of historic buildings, second only to Chester.[56] These cluster mainly in the town centre on Barker Street, Beam Street, Churchyard Side, High Street and Hospital Street, and extend across the Weaver on Welsh Row. Most are within the 38 hectares (94 acres) of conservation area, which broadly follows the bounds of the late medieval and early post-medieval town.[10][57]

The oldest listed building is the 14th-century St Mary's Church, which is listed Grade I. Two other listed buildings are known to predate the fire of 1583: Sweetbriar Hall and the Grade I-listed Churche's Mansion, both timber-framed Elizabethan mansion houses. A few years after the fire, William Camden described Nantwich as the "best built town in the county".[58] Particularly fine timber-framed buildings from the town's rebuilding include 46 High Street and the Grade I-listed Crown coaching inn. Many half-timbered buildings, such as 140–142 Hospital Street, have been concealed behind brick or rendering. Nantwich contains many Georgian town houses, good examples being Dysart Buildings, 9 Mill Street, Townwell House and 83 Welsh Row. Several examples of Victorian corporate architecture are listed, including the former District Bank by Alfred Waterhouse. The most recent listed building is 1–5 Pillory Street, a curved corner block in 17th-century French style, which dates from 1911. Most of the town's listed buildings were originally residential, but churches, chapels, public houses, schools, banks, almshouses and workhouses are represented. Unusual listed structures include a mounting block, twelve cast-iron bollards, a stone gateway, two garden walls and a summerhouse.

Dorfold Hall is a Grade I listed Jacobean mansion in the nearby village of Acton,[59] considered by Pevsner to be one of the two finest Jacobean houses in Cheshire.[60] Its grounds accommodate Nantwich Show each summer, including, until 2021, the International Cheese Awards.

Nantwich Museum, in Pillory Street, has galleries on the history of the town, including Roman salt-making, Tudor Nantwich's Great Fire, the Civil War Battle of Nantwich (1644) and the more recent shoe, clothing and local cheese-making industries. Hack Green Secret Nuclear Bunker, a few miles outside the town, is a once government-owned nuclear bunker, now a museum. Also in Pillory St is the 82-seat Nantwich Players Theatre, which puts on about five plays a year.[61]

The Nantwich Millennium Clock, located in Cocoa Yard between Pillory Street and Hospital Street, is an art installation with a free-standing mechanical clock inside a glass case. The clock was made by Paul Beckett around 2001 to celebrate the new millennium.[62]

The name of Jan Palach Avenue in the south of the town commemorates the self-immolation of a student in Czechoslovakia in 1969.

Geography

[edit]

Nantwich is on the Cheshire Plain, on the banks of the River Weaver. The Shropshire Union Canal runs to the west of the town on an embankment, crossing the Acton lane on the western boundary of the town via an iron aqueduct. There is a basin nearby which is a frequent mooring for visitors to the town. It joins the Llangollen Canal at Hurleston to the north. The town is some 4 miles (6.4 km) south-west of Crewe, 20 miles (32 km) miles south-east of Chester and 22 miles (35 km) east of Wrexham. The town is served by a by-pass to the north and west into which, directly or indirectly, the A51, A500, A529, A530 and A534 roads all feed.

The stretch of A534 from Nantwich to the Welsh border is seen as one of the ten worst stretches of road in England for road safety.[63]

The tower of St Mary's Church was the origin (meridian) of the 6-inch and 1:2500 Ordnance Survey maps of Cheshire.[64]

Public transport

[edit]Nantwich railway station is on the line between Crewe and Whitchurch, Shrewsbury and other towns along the Welsh border. It is served mainly by Transport for Wales trains running from Manchester Piccadilly and Crewe to Shrewsbury and onwards to stations in South Wales.

D&G Bus, Stagecoach and Mikro Coaches operate bus routes from Nantwich Bus Station and in and around Nantwich, some with funding from Cheshire East council.

Education

[edit]The town has eight primary schools (Highfields Community, Willaston Primary Academy, Millfields, Pear Tree, St Anne's (Catholic), Stapeley Broad Lane (Church of England), The Weaver and Nantwich Primary Academy) and two secondary schools, Brine Leas School and Malbank School and Sixth Form College. Reaseheath College runs further education and higher education courses in conjunction with Harper Adams University and the University of Chester. A sixth-form college at Brine Leas opened in September 2010.

For the London 2012 Olympic Games, Malbank School and Sixth Form College was nominated to represent the North West.

Sport

[edit]

The town's football club, Nantwich Town, competes in and in 2006 won the FA Vase. It plays at the Weaver Stadium, opened in 2007.[65]

Rugby union is played at two clubs. Crewe and Nantwich RUFC, founded in 1922, is based at Vagrants Sports Club in Newcastle Road, Willaston, and runs four senior teams including a ladies team; the first XV play in the Midlands 1 West (Level 6). It holds Club Mark and RFU Seal of Approval accreditations and has a mini and junior section of over 250 young people aged 5–18 taking part every Sunday, with a girls section. Acton Nomads RFC, founded in 2009, won the 2010 RFU Presidents XV "This is Rugby" Award;[66][67] it operates two senior sides.

In rugby league, Crewe & Nantwich Steamers play at the Barony Park, Nantwich, also the home ground for Acton Nomads RFC.

The town's cricket club in Whitehouse Lane won the ECB-accredited Cheshire County Premier League title in 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2018. It regularly hosts Cheshire Minor County cricket matches. Midway through the 2017 season, bowler Jimmy Warrington became the first player in the history of the Cheshire County Premier League to take 500 wickets.[68] In 2019, Nantwich reached the final of the ECB National Club Cricket Championship.[69] In the final, played at Lord's, it met Swardeston and lost by 53 runs.[70]

Media

[edit]The daily Sentinel, weekly Nantwich Chronicle and Crewe and Nantwich Guardian, and monthly Dabber cover the town.[71]

Local TV coverage is provided by BBC North West and ITV from the Winter Hill TV transmitter.

Radio stations for the Nantwich area include BBC Radio Stoke, Cheshire's Silk Radio from Macclesfield, Hits Radio Staffordshire & Cheshire and Greatest Hits Radio Staffordshire & Cheshire from Stoke-on-Trent, Crewe-based The Cat 107.9 community radio, and Nantwich-based online radio and networking organisation RedShift Radio.

The Nantwich News is a hyperlocal blog for local events and issues. The inNantwich website gives Nantwich information, including shops, firms, schools, wifi spots, car parking and toilets.

Events

[edit]Cheese awards

[edit]Until 2019, the annual International Cheese Awards were held in July each year during Nantwich Show, at the Dorfold Hall estate.[72][73] In 2021 it was announced the Awards would be moving to the Staffordshire Show Grounds and would no longer be part of the Nantwich Show event.[74]

Jazz and blues

[edit]Since 1996, Nantwich has hosted an annual Nantwich Jazz and Blues Festival over the Easter Bank Holiday weekend. Jazz and blues artists from around the country perform in pubs and venues.[75][76]

Food festival

[edit]The annual Nantwich Food Festival is held in the town centre on the first weekend of September. Re-established as a free-entry festival in 2010, it attracts numerous artisan producers from the local area and further afield, and offers chef demonstrations, family activities and entertainment. It draws some 30,000 visitors a year.[77]

Notable people

[edit]Public service

[edit]

- Sir Nicholas Colfox (flourished 1400, from Nantwich) was a medieval knight involved in the murder of Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester, uncle of King Richard II, in 1397.

- Blessed Thomas Holford (1541–1588), a Protestant schoolteacher, then a Catholic priest, was martyred in Clerkenwell and beatified in 1896.[78]

- Sir Roger Wilbraham (1553 in Nantwich – 1616), prominent English lawyer[79] and Solicitor-General for Ireland under Elizabeth I.

- Roger Mainwaring (died 1590), Elizabethan judge in Ireland, was born in Nantwich.[80]

- Sir Ranulph Crewe (1559 in Nantwich – 1646),[81] Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales.

- Sir William Brereton, 1st Baronet (1604–1661), author, and landowner; established his headquarters in Nantwich during the English Civil War in 1643.[82]

- Matthew Henry (1662–1714), a British nonconformist minister, died of apoplexy in Nantwich.[83]

- Hanmer Warrington (c. 1776 in Acton – 1847), British Army officer, became Consul General on the Barbary Coast for 32 years.

- John Eddowes Bowman the Elder (1785–1841), banker and naturalist.[84]

- George Latham (c. 1800 in Nantwich – 1871), architect and surveyor.

- Eddowes Bowman (1810 in Nantwich – 1869), dissenting tutor[85]

- Thomas Egerton Hale (1832 in Nantwich – 1909), an assistant surgeon, awarded the Victoria Cross[86]

- Thomas Bower (1838–1919), English architect and surveyor, was based in Nantwich

- William Pickersgill (1861 in Nantwich – 1928) chief mechanical engineer of the Caledonian Railway to 1923[87]

- David Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty (1871 in Stapeley – 1936), Admiral of the Fleet

- Sir Andrew Witty (born 1964 in Nantwich), CEO of GlaxoSmithKline, went to Malbank School in Nantwich.

Politics

[edit]

- Roger Wilbraham (1743 in Nantwich – 1829), MP, antiquary, historian, published work on Cheshire dialects.[88]

- Clara Gilbert Cole (1868 in Nantwich – 1956), suffragist, socialist, pacifist, anarchist, poet, and pamphleteer.

- Robert Grant-Ferris, Baron Harvington (1907–1997), Deputy Speaker of the House of Commons 1970–1974, was MP for Nantwich, became Baron Harvington, of Nantwich.[89]

- Michael Winstanley, Baron Winstanley (1918–1993), Liberal MP for Cheadle 1966 to 1970 and for Hazel Grove in 1974[90]

- Gwyneth Dunwoody (1930–2008), British Labour Party politician from 1974 to her death in 2008[91] MP for Exeter 1966–70, and then for Crewe (later Crewe and Nantwich)

- Mike Wood (born 1946), Labour MP for Batley and Spen 1997 to 2015, went to school in Nantwich.[92]

- John Dwyer (born c. 1950), police officer, borough councillor, Assistant Chief Constable and then elected as Cheshire Police and Crime Commissioner[93]

- Laura Smith (born 1985) is a politician and a councillor for Crewe South since 2020. She was a Labour Party Member of Parliament for Crewe and Nantwich in 2017–2019.[94]

Science

[edit]

- John Gerard (1545 in Nantwich – 1612), botanist[95] and author of Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597)[96][97]

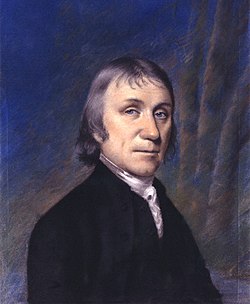

- Joseph Priestley (1733–1804), co-discoverer of oxygen, Nonconformist minister, lived in Nantwich, 1758–1761.[98]

- Sir William Bowman (1816 in Nantwich – 1892), surgeon, histologist, anatomist and ophthalmologist[99]

- Albert Thomas Price (1903 in Nantwich – 1978), geophysicist,[100] developed mathematical models on global electromagnetic induction.

- Sir Kenneth Mather (1911 in Nantwich – 1990) British geneticist and botanist

- Professor Stephen Eichhorn (born 1974 in Nantwich) British materials scientist, brought up locally

Arts

[edit]

- Isabella Whitney (born 1545 in Coole Pilate – 1577), said to be the first female poet and professional writer in England.

- Geoffrey Whitney (c. 1548 in Acton – c. 1601), poet, wrote Choice of Emblemes[101]

- Briget Paget (1570 in Nantwich – c.1647), Puritan, her husband John Paget's literary executor and editor.

- Joseph Partridge (1724–1796), waggoner, antiquary and historian, wrote the town's first history in 1774.[102]

- Peter Bayley (1779 in Nantwich – 1823), writer and poet[103]

- James Hall (1846–1914), lived in the town for 40 years and wrote its history.[104]

- Ida Shepley (1908–1975), a British actress and singer.

- Kim Woodburn (1942–2025), television personality, writer and former cleaner, lived in Nantwich.[105]

- Penny Jordan (1946–2011), writer of over 200 romance novels, died locally[106]

- Mārtiņš Rītiņš (1949 in Nantwich – 2022), Latvian chef, restaurateur, culinary TV presenter and author.

- Ben Miller (born 1966), actor, director and comedian, grew up in Nantwich.

- Thea Gilmore (born 1979), singer/songwriter, lives in Nantwich[107]

- AJ Pritchard (born 1994), ballroom and Latin dancer, featured on the BBC TV Strictly Come Dancing, went to school in Nantwich.[108]

- Blitz Kids (active 2006–2015) were an English alternative rock band originating in Nantwich and Crewe.

Sport

[edit]

- William Downes (1843 in Nantwich – 1896), a New Zealand cricketer

- A. N. Hornby (1847–1925), the first to captain England in both cricket and rugby; buried in Acton churchyard

- George Davenport (1860–1902), cricketer

- Harry Stafford (1869–1940), footballer,[109] played 273 games, became a hotelier in Canada.

- Ernest Piggott (1878–1967), jump racing jockey.

- William Anderson (1901–1983), ice hockey player, team bronze medallist at the 1924 Winter Olympics

- Alf Lythgoe (1907 in Nantwich – 1967), footballer, played 191 games for Stockport County and Huddersfield Town before becoming manager of non-League Altrincham.

- Dario Gradi, (born 1941), manager[110] of Crewe Alexandra (1983–2007 and 2009–2011), lives in Willaston.

- Steve Waddington (born 1956), former footballer, played 286 games, mainly for Walsall F.C.; son of former Stoke City manager, Tony Waddington

- Ashley Westwood (born 1990 in Nantwich), footballer played over 420 games in UK with Crewe, Aston Villa and Burnley[111]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Nantwich parish". City Population. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "Towns and cities, characteristics of built-up areas, England and Wales: Census 2021". Census 2021. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Cheshire Historic Towns Survey Nantwich Retrieved 24 December 2015 Archived 25 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ E. Ekwall, Concise Oxford Dictionary of Place-Names (Oxford) 1936, 320 col. a.

- ^ The Gough Map (interactive version) Archived 5 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 21 April 2008.

- ^ "Holly Holy Day Society website". Hollyholyday.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ McNeil Sale R; et al. (1978), Archaeology in Nantwich: Crown Car Park Excavations, Bemrose Press

- ^ Phillips & Phillips, eds, 2002, p. 32.

- ^ a b Hewitt, 1967, p. 67.

- ^ a b Borough of Crewe & Nantwich: Nantwich Conservation Area: Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Review (January 2006).

- ^ Lake, 1983, pp. 3 and 30.

- ^ Lake, 1983, p. 67.

- ^ Beck, pp. 34–35 and 75–76.

- ^ Lake, 1983, pp. 76 and 91.

- ^ Photo: Great Fire of Nantwich – plaque. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Steve Hindle, "The shaming of Margaret Knowsley: gossip, gender and the experience of authority in early modern England", Continuity and Change 9 (1994), pp. 391–419.

- ^ Battle of Nantwich... and Holly Holy Day Archived 31 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Nantwich Museum, UK.

- ^ a b Pevsner & Hubbard, 1971, p. 12.

- ^ a b Lake, 1983, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Phillips and Phillips, eds, 2002, p. 66.

- ^ Lake, 1983, pp. 30–31 and 35.

- ^ a b c d e f "A Long History, 17 September 2015". Nantwich Mill. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Shaw, Mike; Clark, Jo (2002). Nantwich: Archaeological Assessment (PDF). Chester: Cheshire County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Wilkes, Sue. "Nantwich: A Town That's Worth Its Salt". TimeTravel-Britain.com. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Thompson, James. "Exciting project for mill site". A Dabber's Nantwich. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Cheshire East Local Development Framework: Nantwich Snapshot Report (PDF). Sandbach: Cheshire East Council. 2011. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Cheshire East Local Plan: Draft Nantwich Town Strategy Consultation. Sandbach: Cheshire East Council. 2012. p. 9. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Nantwich Mill Hydro Generation". Companies House. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Hall, James (1883). A history of the town and parish of Nantwich, or Wich-Malbank, in the county palatine of Chester. Nantwich: Johnson.

- ^ "Nantwich's famous outdoor Brine Pool re-opens this weekend". Nantwich News. 3 May 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ a b c d Pearson, Bill. "Brine Baths Hotel". Bill Pearson's Home Page. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Built for a bride". A Dabber's Nantwich. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Caption for Nantwich, Brine Baths Hotel 1898". Francis Frith. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Adams, Jane M. (2015). Healing with water: English spas and the water cure, 1840–1960. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719098062.

- ^ "About us: History". Nantwich Park Road Bowling Club. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "WW1 Great War Centenary – Auxiliary Hospitals". Geograph. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Contact". Nantwich Town Council. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ a b "Election Maps". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Nantwich Chapelry / Civil Parish". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Mary (Grade I) (1206059)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Ormerod, George (1882). History of Cheshire: Volume III. London: George Routledge and Sons. p. 443. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ Youngs, Frederic (1991). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England: Volume II. London: Royal Historical Society. p. 27. ISBN 0 86193 127 0.

- ^ Book of Reference to the Plan of the Parish of Nantwich. London: Ordnance Survey. 1877. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ Youngs, Frederic (1991). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England: Volume II, Northern England. London: Royal Historical Society. p. xv. ISBN 0861931270.

- ^ Kelly' Directory of Cheshire. 1914. p. 479. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Nantwich Urban District". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Brookfield House". Nantwich Museum. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Civic Hall". Nantwich Town Council. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "Civic Hall will give Nantwich a new social life". Nantwich Chronicle. 8 December 1951. p. 7. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "The Old Town Hall and Brine Baths". Hidden Nantwich. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ "The English Non-metropolitan Districts (Names) Order 1973", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1973/551, retrieved 5 September 2022

- ^ "New council asks for change of title". Crewe Chronicle. 6 December 1973. p. 8. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ "It's Crewe and Nantwich Council". Crewe Chronicle. 24 January 1974. p. 1. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

The Secretary of State for the Environment has consented to the name of Crewe District Council being changed to Crewe and Nantwich District Council...

- ^ "The Local Government (Successor Parishes) Order 1973", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 1973/1110

- ^ "The Cheshire (Structural Changes) Order 2008", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2008/634, retrieved 8 May 2024

- ^ Take a Closer Look at Nantwich (booklet), Crewe & Nantwich Borough Council

- ^ Borough of Crewe & Nantwich: Replacement Local Plan 2011: Insets: Town Centre, Acton, Aston, Audlem, Bridgemere School, Buerton, Hankelow, Marbury, Sound School, Worleston School, Wrenbury [1] Archived 8 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Hall, 1883, p. 255.

- ^ Historic England. "Dorfold Hall] (1312869)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ^ Pevsner, p. 22.

- ^ About Us, Nantwich Players Accessed 17 November 2010.

- ^ "Time is ticking again on Millennium Clock in Nantwich!". Nantwich News. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ Darroch, Gordon (18 February 2002). "Remote Highland highway 'most dangerous road'". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ "198 years and 153 meridians, 152 defunct" (PDF) [Charlesclosesociety.org. Retrieved 21 September 2018.]

- ^ "The Weaver Stadium". Nantwich Town F.C. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Cheshire Clubs win RFU Presidents Awards : Cheshire RFU". Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ [2][permanent dead link]

- ^ "October 2017 newsletter" (PDF). Cheshire County Cricket League. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Morse, Peter (2 September 2019). "Nantwich CC book 'once-in-a-lifetime' place in Lords national final". Cheshire Live. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Southwell, Connor (16 September 2019). "Swardeston beat Nantwich by 53 runs at Lord's in National Club County Championship Final". Eastern Daily Press. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "The Dabber – Nantwich's own free newspaper". Thedabber.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ "Home – International Cheese Awards". Internationalcheeseawards.co.uk.

- ^ "Nantwich Show". Nantwichshow.co.uk.

- ^ "Prestigious cheese awards moves to new venue for 2021". Speciality Food. 26 June 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Hilton, Rhiannon (7 March 2016). "Nantwich Jazz, Blues and Music Festival celebrates 20th year". Crewechronicle.co.uk.

- ^ "The 23rd Nantwich Jazz Blues & Music Festival". Nantwichjazz.com. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Own site Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ Nine Martyrs of the Shrewsbury Diocese[permanent dead link] retrieved January 2018.

- ^ The History of Parliament Trust, WILBRAHAM, Sir Roger (1553–1616) retrieved January 2018.

- ^ Ball, F. Elrington The Judges in Ireland 1221–1921 London John Murray 1926

- ^ Rigg, James McMullen (1888). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 13. pp. 81–82.

- ^ The History of Parliament Trust, BRERETON, Sir William, 1st Bt. (1604–1661) retrieved January 2018.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 300.

- ^ Gordon, Alexander. . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 06. pp. 72–73.

- ^ Bowman, Henry (1886). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 06.

- ^ "Surgeon-Major Thomas Egerton Hale, V.C., C.B., M.D". British Medical Journal. 1 (2557): 57. 1910. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.2557.57-b. PMC 2330542.

- ^ "William Pickersgill". Steamindex.com. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ The History of Parliament Trust, WILBRAHAM, Roger (1743–1829) Retrieved January 2018.

- ^ "THE HOUSE OF COMMONS CONSTITUENCIES BEGINNING WITH "N"". Leighrayment.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Obituary: Lord Winstanley". Independent.co.uk. 18 July 1993. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Gwyneth Dunwoody, former MP, Crewe and Nantwich – TheyWorkForYou". TheyWorkForYou. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Mike Wood, former MP, Batley and Spen – TheyWorkForYou". TheyWorkForYou. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Conservative man Dwyer named as Cheshire's first police commissioner". Winsford Guardian. 16 November 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Laura Smith's Parliamentary career". www.parliament.uk.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 21. 1890.

- ^ ODNB: Marja Smolenaars, "Gerard, John (c. 1545–1612)" [3] Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 765.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). 1901.

- ^ "1979QJRAS..20..328 Page 328". Adsabs.harvard.edu. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 61. 1900.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 43. 1895.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 03. 1885.

- ^ Nantwich Museum: James Hall Archived 13 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine accessed 3 April 2013.

- ^ "Kim Woordburn: 'I never go looking for trouble, you know!'". 28 February 2017.

- ^ "Penny Jordan, author of 200 romance novels, dies at 65". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Thea Gilmore". Discogs. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Dallison, Jessica (25 November 2016). "Nantwich dance star AJ Pritchard talks about his Strictly experience". NantwichNews. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

AJ Pritchard spent most of his life craving TV fame. And the former Brine Leas pupil...

- ^ "Harry Stafford". MUFCInfo.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Dario Gradi – Latest Betting Odds – Soccer Base". Soccerbase.com. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Ashley R Westwood – Football Stats – Burnley – Age 28 – Soccer Base". Soccerbase.com. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

Bibliography

- J. Lake (1983), The Great Fire of Nantwich, Shiva Publishing, ISBN 0-906812-57-7

- G. Roberts (2011), Nantwich Life, MPire Books, ISBN 978-0-9547924-1-1

- G. Roberts (2013), Nantwich Life II, MPire Books, ISBN 978-0-9547924-2-8

External links

[edit] Media related to Nantwich at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nantwich at Wikimedia Commons- Nantwich Web Directory

Nantwich

View on GrokipediaHistory

Roman and Early Medieval Origins

Archaeological excavations at Kingsley Fields on the western outskirts of Nantwich in 2002 uncovered the most substantial evidence to date of a Roman-period settlement, dating to the 1st to 4th centuries AD, centered on salt production from local brine springs.[6] The site revealed a Roman road linking to broader networks, timber-built brine tanks—the finest preserved examples in Roman Britain—along with associated buildings, enclosures, a well, and infrastructure for brine collection, storage, and evaporation into salt.[6] Waterlogged conditions preserved organic materials, including structural timbers, while a small number of cremation burials indicated a modest community focused on this industrial activity, which supplied salt to Roman garrisons at sites like Chester and Stoke-on-Trent.[6][7] Following the Roman withdrawal around 410 AD, salt production continued in the early medieval period amid Anglo-Saxon settlement in the region, part of the Mercian kingdom.[8] The site's name, deriving from an Old English term denoting a salt-working settlement ("wic") associated with the nearby River Nant, reflects this economic continuity.[7] Limited archaeological evidence, such as sparse late Saxon pottery, suggests the urban core emerged in the 10th century as a specialized industrial center within the Acton parish chapelry, rather than as an ancient estate hub.[9] The Domesday Book of 1086 records Nantwich as a key salt-producing locale among Cheshire's "wiche" towns, with eight operational salthouses yielding significant revenue—valued at £21 in 1066 (tempore regis Edwardi)—through regulated tolls on salt sales and production boilings, which varied seasonally to meet demand for preservation, such as herring in autumn.[10][9] The settlement was demarcated by a stream and defensive ditch, with local officials enforcing penalties like fines or salt forfeitures for infractions, underscoring its administered economic role under royal and earldom oversight, though lacking a dedicated hundredal court (held instead at Warmundestrou).[9] This documentation highlights Nantwich's pre-Norman prominence in salt extraction, without evidence of Norse disruption seen elsewhere in Cheshire.[9]Salt Trade and Economic Foundations

Nantwich's salt production originated in the Roman period, during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, when brine from natural springs associated with the River Weaver was evaporated using lead pans to produce salt for local garrisons at Chester and Stoke-on-Trent.[1] [7] Archaeological evidence, including a Roman road at Reaseheath and remnants of potential salt works west of the Weaver, underscores the industry's early establishment, with salt serving essential roles in food preservation and as a condiment.[7] By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, Nantwich supported eight operational salt houses, reflecting its status as a key production center amid Cheshire's brine-rich geology formed from Triassic-era evaporites.[7] The town's name, deriving from elements meaning "salt town on the Weaver," highlights this foundational activity, which persisted through the medieval era using methods like storing brine in hollowed-out tree trunks known as "salt ships."[1] Production expanded significantly during the Tudor period, peaking in the late 16th century with 216 salt houses drawing brine from the communal "Old Biot" pit adjacent to the river, fueling economic growth through increased output and regional demand.[1] [7] Salt making involved boiling brine in iron pans over furnaces, initially fueled by wood and later by coal after access improved around 1636, enabling higher yields and broader market penetration.[11] By 1675, Nantwich output reached approximately 100 tons per week, supporting exports via packhorse to North Wales, Derbyshire, and northern England, while locally sustaining industries like Cheshire cheese production—requiring salt for coagulation and preservation—and leather tanning.[11] [7] This salt trade formed the bedrock of Nantwich's economy, generating wealth that financed urban development, trade infrastructure, and ancillary occupations, positioning the town as a vital node in pre-industrial England's preservation and commodity networks despite competition from coastal and other inland producers.[7] The industry's scale, evidenced by the proliferation of specialized "wych houses," underscores its causal role in attracting settlement, fostering self-sufficiency in dairy farming, and establishing Nantwich's reputation as a commercial hub in Cheshire's "salt towns."[1]Tudor Disasters and Reconstruction

The Great Fire of Nantwich began on December 10, 1583, when a brewer in the Waterlode area accidentally ignited a blaze that rapidly spread through the town's predominantly timber-framed structures.[12] The conflagration persisted for 20 days, ultimately destroying approximately 150 houses, inns, and other buildings, while rendering 900 residents homeless out of a pre-fire population of around 2,000.[12] [13] Despite the extensive destruction, which consumed most buildings on the eastern side of the River Weaver, only two fatalities were recorded, attributed in part to the efforts of St. Mary's Church in sheltering evacuees.[14] [15] The fire prompted a coordinated national relief effort, with Queen Elizabeth I contributing £1,000 toward reconstruction and authorizing timber supplies from the royal Delamere Forest to facilitate rebuilding with black-and-white timber-framed architecture characteristic of the era.[16] [17] Donations from across England supported the recovery, marking one of the earliest instances of widespread charitable response to an urban disaster in the realm.[18] Reconstruction efforts transformed Nantwich's urban landscape, replacing lost medieval structures with durable Tudor-style half-timbered buildings featuring wattle-and-daub infill, many of which survive today and contribute to the town's high concentration of listed historic properties.[19] Notable survivals from before the fire, such as Churche's Mansion constructed in the 1570s, underscore the selective devastation and subsequent emphasis on resilient framing techniques during the rebuild.[17] This post-fire renewal solidified Nantwich's reputation for salt-derived prosperity, as economic activities resumed amid the renewed infrastructure, setting the stage for its role in later historical events.[20]Civil War Significance

Nantwich served as a key Parliamentarian garrison in Cheshire during the First English Civil War, established in 1643 amid Royalist control of nearby Chester.[5][21] Its strategic value stemmed from its position on the River Weaver, facilitating supply lines and serving as a bulwark against Royalist advances from the Welsh borders and Chester, which was a major Royalist base under Lord Byron.[22][23] By late December 1643, Royalist forces under Sir William Brereton's regional command had isolated Nantwich, prompting a siege that intensified in January 1644 as Byron assembled around 3,000-4,000 troops to capture the town, the last significant Parliamentarian foothold in Cheshire.[24][25] The defenders, numbering about 2,000 under Colonel Robert Steele, endured harsh winter conditions, with the River Weaver freezing and allowing Royalist assaults, but held out through fortifications and local support.[26][27] On 25 January 1644, a Parliamentarian relief force of approximately 3,000-4,000 men, led by Sir Thomas Fairfax and including cavalry under George Monck, arrived from the west, forcing Byron to divide his army.[24][22] The ensuing battle, fought in snow-covered fields south and east of Nantwich, lasted about two hours and resulted in a decisive Parliamentarian victory, with Royalists suffering heavy casualties—estimated at 500 killed and many captured—while Fairfax reported minimal losses.[26][27] Byron retreated toward Chester, abandoning siege equipment and allowing the town to be relieved. The battle's significance lay in securing Parliamentarian dominance in Cheshire, disrupting Royalist supply routes to Wales and the north, and preventing a potential link-up with Scottish Covenanters or other allies.[22][28] It boosted Parliamentarian morale early in 1644, contributing to broader momentum toward the Battle of Marston Moor, while exposing Royalist overextension in the northwest; contemporaries noted it as a turning point that ended hopes of Royalist consolidation in the region.[24][29] Local commemorations, such as the annual "Holly Holy Day" reenactment, underscore its enduring role in Civil War memory.[30]Industrial Decline and Modern Transitions

The salt industry, which had dominated Nantwich's economy since medieval times, experienced a marked decline starting in the early 17th century, driven by competition from cheaper rock salt mining in nearby Northwich and Winsford, as well as frequent fires destroying wooden salt works and shifts in production methods favoring evaporated sea salt from elsewhere.[20] Records indicate 400 salt houses operating in 1530, reducing to 216 by 1605, and further to just one by the 1850s.[20] By the early 20th century, industrial salt production in the town had contracted to nine works from over 100 in the 13th century, reflecting broader inefficiencies in open-pan boiling techniques compared to underground mining.[31] This contraction forced economic diversification into ancillary trades like leather tanning, dyeing, and shoemaking, with the leather sector reaching its zenith in the 1860s when thousands of shoes were manufactured weekly for domestic and export markets.[32] However, these industries similarly faded amid rising overseas competition and mechanization elsewhere; the final tannery ceased operations in the mid-20th century, leaving Nantwich without dominant manufacturing bases akin to those in adjacent Crewe.[20] The relative absence of heavy industrialization—spared by the salt sector's early collapse—prevented widespread demolition for factories, thereby conserving the town's Tudor and Georgian architecture as a legacy of deindustrialization.[20] Post-1945, Nantwich transitioned toward a service-oriented economy, emphasizing retail, tourism, and professional services, bolstered by its preserved heritage drawing visitors and its role as a commuter hub to rail-linked Crewe and Manchester.[20] Dairy farming and cheesemaking persist as agricultural holdovers, but employment now skews toward wholesale, retail (around 14% of Cheshire East jobs), and knowledge-based sectors, with the town's independent shops and market supporting local commerce amid broader regional manufacturing contraction from overseas imports.[33][34] This shift aligns with Cheshire East's profile, where manufacturing accounts for 11.3% of jobs, down from historical peaks, yielding higher employment rates than regional averages at over 75% in recent years.[33][35]Geography and Environment

Topography and Location

Nantwich is located in Cheshire East unitary authority, within the ceremonial county of Cheshire, northwestern England, at coordinates 53°4′04″N 2°31′15″W.[36] The town occupies a position on the Cheshire Plain, a predominantly flat, low-elevation landscape formed by glacial and fluvial deposits, supporting extensive dairy farming and agriculture across the region.[37] Positioned approximately 4 miles (6 km) southwest of Crewe and 20 miles (32 km) southeast of Chester, Nantwich benefits from proximity to major transport routes while maintaining a rural setting.[38] Its elevation averages 40 metres (131 feet) above sea level, with surrounding terrain exhibiting gentle undulations typical of the plain, ranging from 31 to 70 metres in the immediate vicinity.[36] The River Weaver forms a key geographical feature, with Nantwich situated along its banks; the river's meandering course through the plain has shaped local hydrology, enabling navigation in lower reaches and contributing to periodic flooding events.[39] The Shropshire Union Canal extends westward of the town centre, enhancing the waterway network and historical connectivity in this part of Cheshire.[40]Hydrology and Environmental Features

The River Weaver, originating in the Peckforton Hills and flowing northwest through Nantwich before joining the Mersey, dominates the town's hydrology, providing primary drainage for the surrounding Cheshire Plain. This river, part of the Weaver-Gowy catchment characterized by intensive dairy farming upstream, has historically supported navigation and milling but also poses flood risks due to its meandering course and impermeable underlying clays that limit infiltration. In the 25-26 October 2019 event, prolonged heavy rainfall caused the Weaver to overtop banks in Nantwich, with flooding mechanisms including main river overflow and localized surface water ponding in low-lying areas adjacent to the channel, affecting residential and infrastructural zones.[41] [42] Subsurface hydrology features high groundwater tables, sustained by Triassic Mercia Mudstone Group rocks—predominantly red mudstones and sandstones with low permeability—that impede vertical drainage and promote lateral flow. Historical brine pumping for salt production, exploiting Permian and Triassic evaporite deposits up to 400 meters thick beneath the town, has induced subsidence and maintained saturated conditions, creating zones of waterlogged alluvial deposits 3-4 meters deep that preserve organic archaeological materials.[43] [44] Natural brine springs, remnants of ancient lagoonal environments from 220 million years ago, further influenced early water features, though extraction has depleted surface expressions while exacerbating karstic dissolution hazards like ground collapse. Environmental characteristics reflect the Cheshire Basin's low-relief topography, with flat, fertile plains underlain by salt karst prone to instability from dissolution, mitigated today through regulated pumping limits since the 19th-century subsidence crises. These geological traits support agriculture but constrain development, with waterlogged zones designated for archaeological protection under planning policies to prevent drainage-induced degradation. Broader ecological elements include riparian habitats along the Weaver fostering wetland species, though urban proximity limits biodiversity hotspots; conservation efforts prioritize integrated management of floodplains to balance hydrological function and habitat integrity amid climate-driven rainfall variability. [45] [41]Climate Data and Patterns

Nantwich exhibits a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb classification), characterized by mild temperatures year-round, moderate seasonal variations, and evenly distributed precipitation without extreme droughts or monsoonal influences.[46] This pattern aligns with broader northwest England conditions, influenced by Atlantic westerlies bringing consistent moisture and moderating extremes via proximity to the Irish Sea, approximately 40 km west.[47] Annual average temperatures hover around 9–10 °C, with summers rarely exceeding 25 °C and winters seldom dropping below freezing for prolonged periods.[48] Precipitation totals approximately 800–860 mm annually, occurring on about 140–150 days, predominantly as rain, though light snow or sleet features in 10–20 winter days per year.| Month | Avg. High (°C) | Avg. Low (°C) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 7 | 1 | 62 |

| February | 7 | 1 | 48 |

| March | 10 | 2 | 45 |

| April | 13 | 4 | 50 |

| May | 16 | 7 | 48 |

| June | 19 | 10 | 54 |

| July | 21 | 12 | 56 |

| August | 21 | 12 | 60 |

| September | 18 | 10 | 59 |

| October | 14 | 7 | 77 |

| November | 10 | 4 | 73 |

| December | 7 | 2 | 72 |

Demographics

Population Dynamics

The population of Nantwich parish has exhibited steady long-term growth since the early 19th century, driven initially by agricultural and salt-related economic activity, though rates have decelerated markedly in recent decades. In 1801, the parish recorded 3,463 residents; this rose to 5,579 by 1851, reflecting expansion tied to industrializing trade networks.[49] By 1901, the figure reached 7,722, and it continued to 8,843 in 1951, supported by post-war stability in market town functions.[49] The 2001 census marked 12,516 inhabitants, indicating a cumulative increase of over 260% from 1801 amid broader urbanization trends in Cheshire.[50][49]| Census Year | Parish Population |

|---|---|

| 1801 | 3,463 |

| 1851 | 5,579 |

| 1901 | 7,722 |

| 1951 | 8,843 |

| 2001 | 12,516 |

| 2011 | 13,964 |

| 2021 | 14,045 |