Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

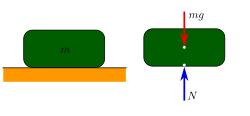

Weight

View on Wikipedia| Weight | |

|---|---|

A diagram explaining the mass and weight | |

Common symbols | |

| SI unit | newton (N) |

Other units | pound-force (lbf) |

| In SI base units | kg⋅m⋅s−2 |

| Extensive? | Yes |

| Intensive? | No |

| Conserved? | No |

Derivations from other quantities | |

| Dimension | |

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is a quantity associated with the gravitational force exerted on the object by other objects in its environment, although there is some variation and debate as to the exact definition.[1][2][3]

Some standard textbooks[4] define weight as a vector quantity, the gravitational force acting on the object. Others[5][6] define weight as a scalar quantity, the magnitude of the gravitational force. Yet others[7] define it as the magnitude of the reaction force exerted on a body by mechanisms that counteract the effects of gravity: the weight is the quantity that is measured by, for example, a spring scale. Thus, in a state of free fall, the weight would be zero. In this sense of weight, terrestrial objects can be weightless: so if one ignores air resistance, one could say the legendary apple falling from the tree[citation needed], on its way to meet the ground near Isaac Newton, was weightless.

The unit of measurement for weight is that of force, which in the International System of Units (SI) is the newton.[1] For example, an object with a mass of one kilogram has a weight of about 9.8 newtons on the surface of the Earth, and about one-sixth as much on the Moon. Although weight and mass are scientifically distinct quantities, the terms are often confused with each other in everyday use (e.g. comparing and converting force weight in pounds to mass in kilograms and vice versa).[8]

Further complications in elucidating the various concepts of weight have to do with the theory of relativity according to which gravity is modeled as a consequence of the curvature of spacetime. In the teaching community, a considerable debate has existed for over half a century on how to define weight for their students. The current situation is that a multiple set of concepts co-exist and find use in their various contexts.[2]

History

[edit]Discussion of the concepts of heaviness (weight) and lightness (levity) date back to the ancient Greek philosophers. These were typically viewed as inherent properties of objects. Plato described weight as the natural tendency of objects to seek their kin. To Aristotle, weight and levity represented the tendency to restore the natural order of the basic elements: air, earth, fire and water. He ascribed absolute weight to earth and absolute levity to fire. Archimedes saw weight as a quality opposed to buoyancy, with the conflict between the two determining if an object sinks or floats. The first operational definition of weight was given by Euclid, who defined weight as: "the heaviness or lightness of one thing, compared to another, as measured by a balance."[2] Operational balances (rather than definitions) had, however, been around much longer.[9]

According to Aristotle, weight was the direct cause of the falling motion of an object, the speed of the falling object was supposed to be directly proportionate to the weight of the object. As medieval scholars discovered that in practice the speed of a falling object increased with time, this prompted a change to the concept of weight to maintain this cause-effect relationship. Weight was split into a "still weight" or pondus, which remained constant, and the actual gravity or gravitas, which changed as the object fell. The concept of gravitas was eventually replaced by Jean Buridan's impetus, a precursor to momentum.[2]

The rise of the Copernican view of the world led to the resurgence of the Platonic idea that like objects attract but in the context of heavenly bodies. In the 17th century, Galileo made significant advances in the concept of weight. He proposed a way to measure the difference between the weight of a moving object and an object at rest. Ultimately, he concluded weight was proportionate to the amount of matter of an object, not the speed of motion as supposed by the Aristotelean view of physics.[2]

Newton

[edit]The introduction of Newton's laws of motion and the development of Newton's law of universal gravitation led to considerable further development of the concept of weight. Weight became fundamentally separate from mass. Mass was identified as a fundamental property of objects connected to their inertia, while weight became identified with the force of gravity on an object and therefore dependent on the context of the object. In particular, Newton considered weight to be relative to another object causing the gravitational pull, e.g. the weight of the Earth towards the Sun.[2]

Newton considered time and space to be absolute. This allowed him to consider concepts as true position and true velocity.[clarification needed] Newton also recognized that weight as measured by the action of weighing was affected by environmental factors such as buoyancy. He considered this a false weight induced by imperfect measurement conditions, for which he introduced the term apparent weight as compared to the true weight defined by gravity.[2]

Although Newtonian physics made a clear distinction between weight and mass, the term weight continued to be commonly used when people meant mass. This led the 3rd General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) of 1901 to officially declare "The word weight denotes a quantity of the same nature as a force: the weight of a body is the product of its mass and the acceleration due to gravity", thus distinguishing it from mass for official usage.

Relativity

[edit]In the 20th century, the Newtonian concepts of absolute time and space were challenged by relativity. Einstein's equivalence principle put all observers, moving or accelerating, on the same footing. This led to an ambiguity as to what exactly is meant by the force of gravity and weight. A scale in an accelerating elevator cannot be distinguished from a scale in a gravitational field. Gravitational force and weight thereby became essentially frame-dependent quantities. This prompted the abandonment of the concept as superfluous in the fundamental sciences such as physics and chemistry. Nonetheless, the concept remained important in the teaching of physics. The ambiguities introduced by relativity led, starting in the 1960s, to considerable debate in the teaching community as how to define weight for their students, choosing between a nominal definition of weight as the force due to gravity or an operational definition defined by the act of weighing.[2]

Definitions

[edit]Several definitions exist for weight, not all of which are equivalent.[3][10][11][12]

Gravitational definition

[edit]The most common definition of weight found in introductory physics textbooks defines weight as the force exerted on a body by gravity.[1][12] This is often expressed in the formula W = mg, where W is the weight, m the mass of the object, and g gravitational acceleration.

In 1901, the 3rd General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) established this as their official definition of weight:

The word weight denotes a quantity of the same nature[Note 1] as a force: the weight of a body is the product of its mass and the acceleration due to gravity.

This resolution defines weight as a vector, since force is a vector quantity. However, some textbooks also take weight to be a scalar by defining:

The weight W of a body is equal to the magnitude Fg of the gravitational force on the body.[16]

The gravitational acceleration varies from place to place. Sometimes, it is simply taken to have a standard value of 9.80665 m/s2, which gives the standard weight.[14]

The force whose magnitude is equal to mg newtons is also known as the m kilogram weight (which term is abbreviated to kg-wt)[17]

Operational definition

[edit]In the operational definition, the weight of an object is the force measured by the operation of weighing it, which is the force it exerts on its support.[10] Since W is the downward force on the body by the centre of Earth and there is no acceleration in the body, there exists an opposite and equal force by the support on the body. It is equal to the force exerted by the body on its support because action and reaction have same numerical value and opposite direction. This can make a considerable difference, depending on the details; for example, an object in free fall exerts little if any force on its support, a situation that is commonly referred to as weightlessness. However, being in free fall does not affect the weight according to the gravitational definition. Therefore, the operational definition is sometimes refined by requiring that the object be at rest.[citation needed] However, this raises the issue of defining "at rest" (usually being at rest with respect to the Earth is implied by using standard gravity).[citation needed] In the operational definition, the weight of an object at rest on the surface of the Earth is lessened by the effect of the centrifugal force from the Earth's rotation.

The operational definition, as usually given, does not explicitly exclude the effects of buoyancy, which reduces the measured weight of an object when it is immersed in a fluid such as air or water. As a result, a floating balloon or an object floating in water might be said to have zero weight.

ISO definition

[edit]In the ISO International standard ISO 80000-4:2006,[18] describing the basic physical quantities and units in mechanics as a part of the International standard ISO/IEC 80000, the definition of weight is given as:

Definition

- ,

- where m is mass and g is local acceleration of free fall.

Remarks

- When the reference frame is Earth, this quantity comprises not only the local gravitational force, but also the local centrifugal force due to the rotation of the Earth, a force which varies with latitude.

- The effect of atmospheric buoyancy is excluded in the weight.

- In common parlance, the name "weight" continues to be used where "mass" is meant, but this practice is deprecated.

— ISO 80000-4 (2006)

The definition is dependent on the chosen frame of reference. When the chosen frame is co-moving with the object in question then this definition precisely agrees with the operational definition.[11] If the specified frame is the surface of the Earth, the weight according to the ISO and gravitational definitions differ only by the centrifugal effects due to the rotation of the Earth.

Apparent weight

[edit]In many real world situations the act of weighing may produce a result that differs from the ideal value provided by the definition used. This is usually referred to as the apparent weight of the object. For instance, when the gravitational definition of weight is used, the operational weight measured by an accelerating scale is often also referred to as the apparent weight.[19] A common example of this is the effect of buoyancy, when an object is immersed in a fluid the displacement of the fluid will cause an upward force on the object, making it appear lighter when weighed on a scale.[20] The apparent weight may be similarly affected by levitation and mechanical suspension.

Mass

[edit]

In modern scientific usage, weight and mass are fundamentally different quantities: mass is an intrinsic property of matter, whereas weight is a force that results from the action of gravity on matter: it measures how strongly the force of gravity pulls on that matter. However, in most practical everyday situations the word "weight" is used when, strictly, "mass" is meant.[8][21] For example, most people would say that an object "weighs one kilogram", even though the kilogram is a unit of mass.

The distinction between mass and weight is unimportant for many practical purposes because the strength of gravity does not vary too much on the surface of the Earth. In a uniform gravitational field, the gravitational force exerted on an object (its weight) is directly proportional to its mass. For example, object A weighs 10 times as much as object B, so therefore the mass of object A is 10 times greater than that of object B. This means that an object's mass can be measured indirectly by its weight, and so, for everyday purposes, weighing (using a weighing scale) is an entirely acceptable way of measuring mass. Similarly, a balance measures mass indirectly by comparing the weight of the measured item to that of an object(s) of known mass. Since the measured item and the comparison mass are in virtually the same location, so experiencing the same gravitational field, the effect of varying gravity does not affect the comparison or the resulting measurement.

The Earth's gravitational field is not uniform but can vary by as much as 0.5%[22] at different locations on Earth (see Earth's gravity). These variations alter the relationship between weight and mass, and must be taken into account in high-precision weight measurements that are intended to indirectly measure mass. Spring scales, which measure local weight, must be calibrated at the location at which the objects will be used to show this standard weight, to be legal for commerce.[citation needed]

This table shows the variation of acceleration due to gravity (and hence the variation of weight) at various locations on the Earth's surface.[23]

| Location | Latitude | m/s2 | Absolute difference from equator | Percentage difference from equator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equator | 0° | 9.7803 | 0.0000 | 0% |

| Sydney | 33°52′ S | 9.7968 | 0.0165 | 0.17% |

| Aberdeen | 57°9′ N | 9.8168 | 0.0365 | 0.37% |

| North Pole | 90° N | 9.8322 | 0.0519 | 0.53% |

The historical use of "weight" for "mass" also persists in some scientific terminology – for example, the chemical terms "atomic weight", "molecular weight", and "formula weight", can still be found rather than the preferred "atomic mass", etc.

In a different gravitational field, for example, on the surface of the Moon, an object can have a significantly different weight than on Earth. The gravity on the surface of the Moon is only about one-sixth as strong as on the surface of the Earth. A one-kilogram mass is still a one-kilogram mass (as mass is an intrinsic property of the object) but the downward force due to gravity, and therefore its weight, is only one-sixth of what the object would have on Earth. So a man of mass 180 pounds weighs only about 30 pounds-force when visiting the Moon.

SI units

[edit]In most modern scientific work, physical quantities are measured in SI units. The SI unit of weight is the same as that of force: the newton (N) – a derived unit which can also be expressed in SI base units as kg⋅m/s2 (kilograms times metres per second squared).[21]

In commercial and everyday use, the term "weight" is usually used to mean mass, and the verb "to weigh" means "to determine the mass of" or "to have a mass of". Used in this sense, the proper SI unit is the kilogram (kg).[21]

Pound and other non-SI units

[edit]In United States customary units, the pound can be either a unit of force or a unit of mass.[24] Related units used in some distinct, separate subsystems of units include the poundal and the slug. The poundal is defined as the force necessary to accelerate an object of one-pound mass at 1 ft/s2, and is equivalent to about 1/32.2 of a pound-force. The slug is defined as the amount of mass that accelerates at 1 ft/s2 when one pound-force is exerted on it, and is equivalent to about 32.2 pounds (mass).

The kilogram-force is a non-SI unit of force, defined as the force exerted by a one-kilogram mass in standard Earth gravity (equal to 9.80665 newtons exactly). The dyne is the cgs unit of force and is not a part of SI, while weights measured in the cgs unit of mass, the gram, remain a part of SI.

Sensation

[edit]The sensation of weight is caused by the force exerted by fluids in the vestibular system, a three-dimensional set of tubes in the inner ear.[dubious – discuss] It is actually the sensation of g-force, regardless of whether this is due to being stationary in the presence of gravity, or, if the person is in motion, the result of any other forces acting on the body such as in the case of acceleration or deceleration of a lift, or centrifugal forces when turning sharply.

Measuring

[edit]

Weight is commonly measured using one of two methods. A spring scale or hydraulic or pneumatic scale measures local weight, the local force of gravity on the object (strictly apparent weight force). Since the local force of gravity can vary by up to 0.5% at different locations, spring scales will measure slightly different weights for the same object (the same mass) at different locations. To standardize weights, scales are always calibrated to read the weight an object would have at a nominal standard gravity of 9.80665 m/s2 (approx. 32.174 ft/s2). However, this calibration is done at the factory. When the scale is moved to another location on Earth, the force of gravity will be different, causing a slight error. So to be highly accurate and legal for commerce, spring scales must be re-calibrated at the location at which they will be used.

A balance on the other hand, compares the weight of an unknown object in one scale pan to the weight of standard masses in the other, using a lever mechanism – a lever-balance. The standard masses are often referred to, non-technically, as "weights". Since any variations in gravity will act equally on the unknown and the known weights, a lever-balance will indicate the same value at any location on Earth. Therefore, balance "weights" are usually calibrated and marked in mass units, so the lever-balance measures mass by comparing the Earth's attraction on the unknown object and standard masses in the scale pans. In the absence of a gravitational field, away from planetary bodies (e.g. space), a lever-balance would not work, but on the Moon, for example, it would give the same reading as on Earth. Some balances are marked in weight units, but since the weights are calibrated at the factory for standard gravity, the balance will measure standard weight, i.e. what the object would weigh at standard gravity, not the actual local force of gravity on the object.

If the actual force of gravity on the object is needed, this can be calculated by multiplying the mass measured by the balance by the acceleration due to gravity – either standard gravity (for everyday work) or the precise local gravity (for precision work). Tables of the gravitational acceleration at different locations can be found on the web.

Gross weight is a term that is generally found in commerce or trade applications, and refers to the total weight of a product and its packaging. Conversely, net weight refers to the weight of the product alone, discounting the weight of its container or packaging; and tare weight is the weight of the packaging alone.

Relative weights on the Earth and other celestial bodies

[edit]The table below shows comparative gravitational accelerations at the surface of the Sun, the Moon, and at each of the planets in the Solar System. The "surface" is taken to mean the cloud tops of the giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune). For the Sun, the surface is taken to mean the photosphere. The values in the table have not been de-rated for the centrifugal effect of planet rotation (and cloud-top wind speeds for the giant planets) and therefore, generally speaking, are similar to the actual gravity that would be experienced near the poles.

| Body | Multiple of Earth gravity |

Surface gravity m/s2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sun | 27.90 | 274.1 |

| Mercury | 0.3770 | 3.703 |

| Venus | 0.9032 | 8.872 |

| Earth | 1 (by definition) | 9.8226[25] |

| Moon | 0.1655 | 1.625 |

| Mars | 0.3895 | 3.728 |

| Jupiter | 2.640 | 25.93 |

| Saturn | 1.139 | 11.19 |

| Uranus | 0.917 | 9.01 |

| Neptune | 1.148 | 11.28 |

See also

[edit]- Human body weight – Person's mass or weight

- Specific weight – Weight per unit volume of a material

- Tare weight

- weight – Unit of weight the English unit

- List of weights

Notes

[edit]- ^ The phrase "quantity of the same nature" is a literal translation of the French phrase grandeur de la même nature. Although this is an authorized translation, VIM 3 of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures recommends translating grandeurs de même nature as quantities of the same kind.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Richard C. Morrison (1999). "Weight and gravity - the need for consistent definitions". The Physics Teacher. 37 (1): 51. Bibcode:1999PhTea..37...51M. doi:10.1119/1.880152.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Igal Galili (2001). "Weight versus gravitational force: historical and educational perspectives". International Journal of Science Education. 23 (10): 1073. Bibcode:2001IJSEd..23.1073G. doi:10.1080/09500690110038585. S2CID 11110675.

- ^ a b Gat, Uri (1988). "The weight of mass and the mess of weight". In Richard Alan Strehlow (ed.). Standardization of Technical Terminology: Principles and Practice – second volume. ASTM International. pp. 45–48. ISBN 978-0-8031-1183-7.

- ^ Knight, Randall D. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: a Strategic Approach. San Francisco, US: Addison–Wesley. pp. 100–101. ISBN 0-8053-8960-1.

- ^ Bauer, Wolfgang; Westfall, Gary D. (2011). University Physics with Modern Physics. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-07-336794-1.

- ^ Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics. US: Thompson. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-495-11245-7.

- ^ Hewitt, Paul G. (2001). Conceptual Physics. US: Addison–Wesley. pp. 159. ISBN 0-321-05202-1.

- ^ a b The National Standard of Canada, CAN/CSA-Z234.1-89 Canadian Metric Practice Guide, January 1989:

- 5.7.3 Considerable confusion exists in the use of the term "weight". In commercial and everyday use, the term "weight" nearly always means mass. In science and technology "weight" has primarily meant a force due to gravity. In scientific and technical work, the term "weight" should be replaced by the term "mass" or "force", depending on the application.

- 5.7.4 The use of the verb "to weigh" meaning "to determine the mass of", e.g., "I weighed this object and determined its mass to be 5 kg," is correct.

- ^ http://www.averyweigh-tronix.com/museum Archived 2013-02-28 at the Wayback Machine accessed 29 March 2013.

- ^ a b Allen L. King (1963). "Weight and weightlessness". American Journal of Physics. 30 (5): 387. Bibcode:1962AmJPh..30..387K. doi:10.1119/1.1942032.

- ^ a b A. P. French (1995). "On weightlessness". American Journal of Physics. 63 (2): 105–106. Bibcode:1995AmJPh..63..105F. doi:10.1119/1.17990.

- ^ a b Galili, I.; Lehavi, Y. (2003). "The importance of weightlessness and tides in teaching gravitation" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 71 (11): 1127–1135. Bibcode:2003AmJPh..71.1127G. doi:10.1119/1.1607336. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-01-16. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Working Group 2 of the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM/WG 2) (2008). International vocabulary of metrology – Basic and general concepts and associated terms (VIM) – Vocabulaire international de métrologie – Concepts fondamentaux et généraux et termes associés (VIM) (PDF) (JCGM 200:2008) (in English and French) (3rd ed.). BIPM. Note 3 to Section 1.2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Resolution of the 3rd meeting of the CGPM (1901)". BIPM.

- ^ David B. Newell; Eite Tiesinga, eds. (2019). The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (NIST Special publication 330, 2019 ed.). Gaithersburg, MD: NIST. p. 46.

- ^ Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; Walker, Jearl (2007). Fundamentals of Physics. Vol. 1 (8th ed.). Wiley. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-470-04473-5.

- ^ Chester, W. Mechanics. George Allen & Unwin. London. 1979. ISBN 0-04-510059-4. Section 3.2 at page 83.

- ^ ISO 80000-4:2006, Quantities and units - Part 4: Mechanics

- ^ Galili, Igal (1993). "Weight and gravity: teachers' ambiguity and students' confusion about the concepts". International Journal of Science Education. 15 (2): 149–162. Bibcode:1993IJSEd..15..149G. doi:10.1080/0950069930150204.

- ^ Bell, F. (1998). Principles of mechanics and biomechanics. Stanley Thornes Ltd. pp. 174–176. ISBN 978-0-7487-3332-3.

- ^ a b c A. Thompson & B. N. Taylor (March 3, 2010) [July 2, 2009]. "The NIST Guide for the use of the International System of Units, Section 8: Comments on Some Quantities and Their Units". Special Publication 811. NIST. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Hodgeman, Charles, ed. (1961). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (44th ed.). Cleveland, US: Chemical Rubber Publishing Co. pp. 3480–3485.

- ^ Clark, John B (1964). Physical and Mathematical Tables. Oliver and Boyd.

- ^ "Common Conversion Factors, Approximate Conversions from U.S. Customary Measures to Metric". NIST. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 13 January 2010. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ This value excludes the adjustment for centrifugal force due to Earth’s rotation and is therefore greater than the 9.80665 m/s2 value of standard gravity.

Weight

View on GrokipediaFundamental Concepts

Gravitational Definition

In physics, weight is defined as the gravitational force exerted on an object due to the attraction between its mass and the mass of a celestial body, such as Earth. This force arises from Newton's law of universal gravitation, which states that every particle in the universe attracts every other particle with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers. The magnitude of this force is given by the equation where is the universal gravitational constant (), is the mass of the attracting body (e.g., Earth), is the mass of the object, and is the distance between their centers.[3][4] Near the surface of Earth, this general expression simplifies to the weight of an object, expressed as , where is the local gravitational acceleration. The value of is derived by substituting Earth's mass (approximately ) and radius (approximately ) into the universal gravitation formula, yielding at standard sea level. This approximation holds because is nearly constant for objects on Earth's surface, making effectively uniform for most practical purposes, though it varies slightly with latitude and altitude.[2][5] As a force, weight is a vector quantity, with magnitude and direction pointing toward the center of the attracting body, perpendicular to the local surface in the absence of other influences. This downward orientation explains why objects fall toward Earth and why weight opposes upward forces in equilibrium scenarios. The gravitational definition of weight emerged as the foundational concept in classical physics through Isaac Newton's work in the late 17th century, particularly in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), where he unified terrestrial and celestial mechanics by positing gravity as a universal force. Prior to Newton, "weight" often referred interchangeably to mass or heaviness without a clear distinction from quantity of matter, but his formulation established weight explicitly as the measurable effect of gravitational attraction, influencing all subsequent mechanics until relativity.[6][7]Operational and ISO Definitions

In practical applications, the operational definition of weight is the magnitude of the force indicated by a weighing scale or balance when an object is at rest under the standard acceleration due to gravity, defined as . This reading represents the force required to support the object against gravity in a static equilibrium, ensuring reproducible measurements in engineering, manufacturing, and quality control contexts. Scales are calibrated to this standard value to account for variations in local gravity, providing a consistent operational measure expressed in newtons or, conventionally, converted to mass units via division by .[5] The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) formalizes weight in ISO 80000-4:2019 as a specific type of force, namely the weight force , given by , where is the mass of the body and is the local acceleration of free fall vector; its magnitude, denoted , has the SI unit of newton (N). For standardized purposes, ISO distinguishes the conventional weight as , using the fixed standard gravity to enable uniform comparisons independent of location. The acceleration g is the effective local acceleration of free fall, which includes the gravitational attraction and the centrifugal effect due to Earth's rotation. The standard explicitly excludes the effect of atmospheric buoyancy from the weight definition. In legal metrology, this definition supports distinctions between true gravitational force and practical force measurements, where weight is treated as a vector quantity aligned with the local plumb line but quantified under controlled conditions.[8] In trade and commerce, "standard weight" refers to the assigned conventional mass value of calibration artifacts, such as weights used to verify scales, which are calibrated to balance against reference standards in air under defined environmental conditions. These values are determined assuming a reference air density of 1.2 kg/m³ and a brass density of 8000 kg/m³ for the reference weight, effectively incorporating buoyancy effects into the conventional mass without altering the underlying force definition. The International Organization of Legal Metrology (OIML) aligns with ISO through Recommendation D 28, defining conventional mass as the numerical value of the result of weighing in air, equivalent to the mass of the reference weight that balances the object, thus facilitating accurate trade transactions while adhering to ISO's force-based framework.[9] For non-gravitational influences, ISO 80000-4 addresses weight determination in contexts like buoyancy through notes on measurement practices, stipulating that apparent forces from air displacement must be corrected when deriving true mass from scale readings to isolate the gravitational weight. Buoyancy corrections in air are applied using formulas that account for the densities of the object and calibration standard, such as the conventional mass (approximating for standard air density ), where is the object's density. This is critical in high-precision metrology, where uncorrected buoyancy can introduce relative errors up to about 0.1% for objects with densities near that of air (e.g., ).[10]Apparent Weight

Apparent weight refers to the normal force exerted by a supporting surface on an object or person, which can differ from the true gravitational weight due to the effects of acceleration in non-inertial reference frames. In such scenarios, the apparent weight is given by the equation , where is the mass, is the acceleration due to gravity, and is the acceleration of the frame relative to an inertial frame, taken positive in the upward direction.[11] This formulation arises from Newton's second law applied to the object in the accelerated frame, where the net force includes both gravity and the fictitious force due to acceleration.[12] A common example occurs in an elevator accelerating vertically. When the elevator accelerates upward with acceleration , the apparent weight increases, making the occupant feel heavier, as the normal force must provide the additional force to produce the net upward acceleration.[13] Conversely, during downward acceleration, such as when the elevator cable slows to stop, the apparent weight decreases. In free fall, where , the apparent weight becomes zero, resulting in weightlessness, as experienced by objects in orbit or during the drop phase of certain rides. Buoyancy in fluids further modifies apparent weight by introducing an upward buoyant force that opposes gravity. According to Archimedes' principle, the buoyant force equals the weight of the fluid displaced by the object, so the apparent weight is , where is the fluid density and is the submerged volume.[14] This reduction explains why submerged objects appear lighter when weighed on a scale in a fluid, a principle fundamental to hydrostatics and used in density measurements.[15] In aviation, apparent weight varies during maneuvers involving acceleration, such as turns or loops, where centripetal acceleration can multiply the effective gravitational force, leading to g-forces that increase the normal force on the pilot or passengers.[16] Similarly, in amusement rides like roller coasters, rapid changes in direction produce accelerations that alter apparent weight; at the bottom of a loop, upward acceleration increases it, while at the top, it may approach zero, simulating free fall.[17] These effects highlight how apparent weight depends on the dynamics of the supporting structure rather than gravity alone.Relation to Mass

Distinction Between Mass and Weight

Mass is a scalar quantity that represents the amount of matter in an object or the resistance of that object to changes in motion, known as inertia. In the International System of Units (SI), mass is measured in kilograms (kg), and it remains constant regardless of the object's location in the universe.[18][19] In contrast, weight is the gravitational force acting on an object's mass, which varies depending on the strength of the local gravitational field. For instance, an object with a given mass will have less weight on the Moon, where gravity is about one-sixth that of Earth's, compared to its weight on Earth.[20][19] This distinction arises because weight is a vector quantity, directed toward the center of the gravitational source, and its magnitude is determined by the product of the mass and the local acceleration due to gravity, expressed as , where is mass and is the gravitational acceleration.[21] While mass is an intrinsic property, weight is extrinsic and context-dependent, emphasizing that mass is the fundamental attribute from which weight derives.[22] Common misconceptions often blur this boundary, particularly in historical and educational contexts. Prior to Newtonian mechanics, "weight" was used interchangeably for both the quantity of matter and the downward force it experienced, leading to the erroneous view that mass and weight were identical.[23] In modern education, students frequently confuse the two, such as assuming weight is invariant or equating units like the pound-mass (a measure of mass) with the pound-force (a measure of force equivalent to the weight of one pound-mass under standard gravity).[24] These errors persist due to everyday language where "weight" colloquially means mass, but scientifically, they represent distinct physical concepts.[20]Units of Mass and Weight

In the International System of Units (SI), the base unit for mass is the kilogram (kg), defined by fixing the numerical value of the Planck constant to exactly when expressed in the unit , where the second and joule are defined previously.[25] The derived SI unit for weight, treated as a force, is the newton (N), defined as , representing the force required to accelerate a 1 kg mass by 1 m/s².[18] Non-SI units remain in widespread use, particularly in the United States customary and British imperial systems. For mass, the pound-mass (lbm or lbm) is common, defined exactly as . The corresponding unit for weight is the pound-force (lbf), defined as the force exerted by standard gravity on a 1 lbm mass, equivalent to approximately .[26] Other mass units include the avoirdupois ounce (oz), equal to lbm or exactly , and the stone (st), used primarily in the UK for human body weight and defined as 14 lbm or approximately .[27] The following table provides key conversion factors between SI and selected non-SI units for mass and weight:| Mass Unit | Symbol | Equivalent in kg | Weight Unit | Symbol | Equivalent in N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kilogram | kg | 1 | Newton | N | 1 |

| Pound-mass | lbm | 0.45359237 | Pound-force | lbf | 4.448222 |

| Ounce (avoirdupois) | oz | 0.028349523125 | - | - | - |

| Stone | st | 6.35029318 | - | - | - |

Historical Development

Newtonian Mechanics

Prior to Newton's work, the concept of weight was understood through Aristotelian physics, where heavy objects were thought to possess a natural tendency to move downward toward the center of the universe, their speed of fall proportional to their heaviness in a given medium.[29] This view treated weight as an intrinsic property driving natural motion, without reference to an underlying force or universal principle.[29] Isaac Newton's formulation of weight emerged from his synthesis of terrestrial and celestial mechanics, famously illustrated by the anecdote of an apple falling from a tree at Woolsthorpe Manor, which prompted him to consider why it fell toward Earth rather than ascending or deviating sideways.[30] Though this story, first recounted publicly by Voltaire over half a century after Newton's death, lacks direct confirmation from Newton himself, it symbolizes his insight into a unifying gravitational force.[30] In his seminal 1687 work, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Newton proposed the law of universal gravitation, stating that every particle attracts every other with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers: .[31] Applied to an object of mass near Earth's surface, this yields the weight as the gravitational force , where is the acceleration due to gravity, approximately , derived as with the gravitational constant, Earth's mass, and its radius.[32] Newton integrated this with his second law of motion, , positing that the net force on an object equals its mass times acceleration.[33] For a freely falling body near Earth, the gravitational force provides the acceleration , directly equating weight to and explaining why all objects fall at the same rate in vacuum, independent of mass.[33] He derived 's value by linking it to planetary motion, using Kepler's third law and centripetal acceleration for circular orbits to show that the same inverse-square force governs both apples and moons.[32] To measure , Newton conducted pendulum experiments, observing that the period of a simple pendulum relates to length and via , allowing computation of from precise timing and length measurements; he noted variations with latitude due to Earth's rotation and oblateness.[34] These experiments, detailed in Principia Book 3, confirmed the uniformity of gravitational acceleration across locations.[31]Relativistic Physics

In relativistic physics, the concept of weight is fundamentally reshaped by Einstein's equivalence principle, which posits that the effects of gravity are locally indistinguishable from those of acceleration in a non-inertial frame. This principle establishes the equivalence between gravitational mass—the property that determines the strength of gravitational attraction—and inertial mass—the property that resists changes in motion—implying that both respond identically to gravitational fields. As a result, weight measurements, which in classical terms rely on the gravitational force acting on mass, become tied to the observer's local frame, where the sensation of weight arises from the acceleration required to counteract free fall.[35][36] In general relativity, weight is interpreted as the proper acceleration experienced by an object deviating from geodesic motion in curved spacetime, rather than a simple force between masses. A geodesic represents the straightest possible path in spacetime, akin to free fall under gravity; thus, an object at rest on Earth's surface feels weight due to the upward proper acceleration provided by the ground, which prevents it from following this geodesic. Gravitational time dilation further complicates this, as clocks—and by extension, measurements of acceleration and weight—run slower in stronger gravitational fields, affecting the perceived duration and magnitude of weight in precise applications. This observer-dependent nature means that weight is not an absolute property but varies with the local metric of spacetime.[36] Key historical milestones underscore these relativistic redefinitions of weight and gravity. Albert Einstein published the field equations of general relativity on November 25, 1915, in the Proceedings of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, providing the mathematical framework for understanding gravity as spacetime curvature that influences weight through acceleration. The theory's prediction of light deflection by gravity was confirmed during the solar eclipse of May 29, 1919, by expeditions led by Arthur Eddington, which measured starlight bending near the Sun by approximately 1.75 arcseconds—twice the Newtonian value—validating the equivalence principle's implications for gravitational effects. Modern applications, such as the Global Positioning System (GPS), require relativistic corrections for gravitational time dilation; satellite clocks, orbiting in weaker gravity, run faster by about 45 microseconds per day compared to Earth-based clocks, necessitating adjustments to maintain positional accuracy within meters, as unaccounted effects would accumulate errors of kilometers daily.[37][38] Unlike the Newtonian view of weight as an absolute force determined solely by mass and gravitational field strength, the relativistic perspective renders weight observer-dependent, arising from local proper acceleration in curved spacetime and influenced by time dilation. Newtonian mechanics serves as the low-speed, weak-field limiting case of general relativity, accurately describing weight under everyday conditions on Earth.Measurement Techniques

Principles of Weighing

The principle of weighing using a balance relies on achieving mechanical equilibrium through equal torques about the fulcrum. In a beam balance, the torque due to the weight of the unknown mass at distance from the fulcrum balances the torque from a known mass at distance , expressed as , where is the local gravitational acceleration.[39] This relationship shows that the balance determines mass ratios directly, with canceling out, making the measurement independent of variations in gravitational field strength.[40] Spring scales operate on Hooke's law, which states that the restoring force of a spring is proportional to its displacement from equilibrium: , where is the spring constant. In weighing applications, the gravitational force stretches the spring by , and the scale is calibrated under standard (typically 9.80665 m/s²) to read the weight directly as a force or equivalent mass.[41]/07%3A_Strength_and_Elasticity_of_the_Body/7.05%3A_Measuring_Weight) This calibration assumes linear elasticity within the spring's operating range, though deviations occur at high loads. Accuracy in weighing is influenced by environmental and operational factors, including air currents that induce buoyancy or aerodynamic torques, temperature variations causing thermal expansion or contraction in scale components, and magnetic fields that exert forces on ferromagnetic materials in the device.[42] These effects can introduce systematic errors, necessitating controlled conditions such as draft shields and temperature-stable environments for precise measurements.[43] Gravimetric weighing principles involve direct measurement of mass via gravitational force comparison or transduction, providing high precision for solids and calibrated volumes through weight differences.[44] Apparent weight adjustments may account for buoyancy in these methods./08%3A_Gravimetric_Methods)Types of Weighing Devices

Mechanical scales represent some of the earliest and simplest forms of weighing devices, relying on levers, beams, and counterweights to achieve balance without electrical components.[45] Beam balances, such as the two-pan equal-arm type, consist of a central fulcrum with identical arms suspending pans on each end, where the object is weighed against known standard masses to establish equilibrium.[46] These suspended-pan designs, also known as even-balance scales, were refined over centuries for applications in trade and science, offering reliability in environments without power sources.[46] Platform scales, a variant of mechanical beam systems, feature a flat platform supported by levers and springs that transmit the load to a dial indicator, enabling the weighing of larger items like crates or produce up to several hundred kilograms.[47] The historical evolution of mechanical weighing devices traces back to ancient civilizations, with the steelyard—a single-beam lever scale with a fixed fulcrum, sliding counterweight, and hook for suspending the object—originating in the ancient Near East around 3000 BCE and widely used by the Romans as a portable and efficient tool for commerce across the empire from the 1st century BCE.[48] This design, which allowed weighing up to 100 kilograms or more by adjusting the poise along a graduated beam, influenced subsequent European scales and persisted in various forms until the 19th century.[49] Electronic weighing devices have largely supplanted mechanical ones in modern applications due to their precision and speed. A dynamic checkweigher is an automated machine designed to weigh products in motion on a conveyor belt, ensuring they fall within predefined weight tolerances. Unlike static scales, which require products to stop, dynamic models handle high throughput—up to hundreds of items per minute—making them ideal for fast-paced environments.[50] These devices primarily utilize load cells equipped with strain gauges to convert applied force into measurable electrical signals.[51] In these systems, strain gauges bonded to the load cell's structural element deform under weight, altering electrical resistance in a Wheatstone bridge circuit, which is then amplified and processed for output.[52] Digital readouts display the results instantly on LCD or LED screens, often with features like tare functions and data connectivity, supporting capacities from grams to tons in commercial settings.[51] For specialized needs, precision instruments extend the capabilities of both mechanical and electronic principles. Analytical balances, commonly used in laboratories, achieve resolutions as fine as 0.1 mg through enclosed chambers and electromagnetic force compensation in electronic models, ensuring minimal interference for weighing small samples like chemicals or pharmaceuticals up to 200 grams.[53] At the opposite end of the scale, industrial truck scales employ multiple high-capacity load cells—typically four to six, each rated 20 to 50 tons—mounted under a concrete or steel platform to weigh entire vehicles, facilitating logistics and compliance with transport regulations for loads exceeding 100 tons.[54] Advancements in precision have culminated in modern devices like quartz crystal microbalances, which use the piezoelectric properties of quartz resonators to detect mass changes at the nanogram level by monitoring shifts in resonant frequency, primarily for research in thin-film deposition and surface analysis.[55] These instruments, developed in the late 20th century, mark a shift from macroscopic mechanical systems to nanoscale electronic detection, calibrated against standard gravitational references for traceability.[55]Variations Across Environments

Weight on Earth

Weight on Earth varies primarily due to the planet's oblate spheroid shape, rotational effects, distance from the center of mass, and local geological density variations, leading to differences in the acceleration due to gravity, denoted as . These factors cause to range from approximately 9.780 m/s² at the equator to 9.832 m/s² at the poles, a variation of about 0.5% across the surface.[56][57] The primary latitudinal variation arises from Earth's oblateness—flattened at the poles and bulging at the equator due to centrifugal forces from rotation—and the direct centrifugal reduction in effective gravity. At the equator, the centrifugal acceleration reaches a maximum of about 0.033 m/s² outward, perpendicular to the axis of rotation, reducing the net by roughly 0.3%.[58] Combined with the greater distance from Earth's center at the equator (equatorial radius ~21 km larger than polar), this results in the minimum of 9.780 m/s², while the poles, lacking centrifugal effects and closer to the center, experience the maximum of 9.832 m/s².[56] Intermediate latitudes follow a sinusoidal pattern, with decreasing toward the equator and increasing toward the poles.[57] As altitude increases above sea level, decreases inversely with the square of the distance from Earth's center, following , where is the radial distance. For heights up to 10 km, this yields an approximate linear decrease of -0.003 m/s² per kilometer, such that at 10 km altitude is about 0.03 m/s² less than at sea level.[57] This effect is most relevant in aviation and mountaineering contexts, where the change remains small but measurable. Local gravitational anomalies, typically on the order of milligals (10^{-5} m/s²), arise from subsurface density variations due to geological features. For instance, regions with excess mass, such as dense ore deposits, produce positive anomalies, increasing locally. Mountain ranges like the Himalayas exhibit positive free-air anomalies due to the mass of the topography itself, which provides a local enhancement relative to a hypothetical flat surface at the same elevation. However, Bouguer anomalies, which correct for the mass of the overlying rock, are large and negative (e.g., -180 to -450 mGal over the Himalayas) because the mountains are isostatically compensated by lower-density crustal roots beneath them. Consequently, the net effective at mountain summits remains lower than at sea level due to the dominant effect of altitude. Sedimentary basins or low-density crustal features cause negative anomalies. These anomalies are mapped using gravimetry and inform geophysical surveys.[59][60]Weight on Other Celestial Bodies

The weight of an object on other celestial bodies is given by the Newtonian formula , where is the invariant mass of the object and is the local surface gravitational acceleration, which varies based on the body's mass and radius.[61] This contrasts with Earth's standard , providing a baseline for comparisons. On the Moon, surface gravity is approximately , resulting in an object's weight being about one-sixth of its Earth value.[62] Mars has a surface gravity of roughly , yielding a weight about 0.38 times that on Earth.[63] Jupiter's equatorial surface gravity is about , more than 2.5 times Earth's, though it decreases toward the poles due to the planet's rapid rotation.[63] Surface gravities for major solar system bodies are summarized below, with values relative to Earth for context:| Body | Surface Gravity (m/s²) | Relative to Earth |

|---|---|---|

| Moon | 1.62 | 0.165 |

| Mercury | 3.70 | 0.377 |

| Venus | 8.87 | 0.905 |

| Earth | 9.81 | 1.000 |

| Mars | 3.71 | 0.378 |

| Jupiter (equator) | 24.79 | 2.528 |

| Saturn (equator) | 10.44 | 1.065 |

| Uranus | 8.87 | 0.905 |

| Neptune | 11.15 | 1.137 |

| Pluto | 0.62 | 0.063 |