Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Neurocognition

View on Wikipedia| Neuropsychology |

|---|

|

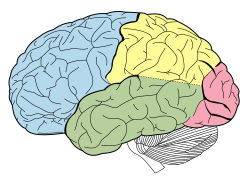

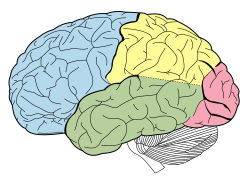

Neurocognitive functions are cognitive functions closely linked to the function of particular areas, neural pathways, or cortical networks in the brain, ultimately served by the substrate of the brain's neurological matrix (i.e. at the cellular and molecular level). Therefore, their understanding is closely linked to the practice of neuropsychology and cognitive neuroscience – two disciplines that broadly seek to understand how the structure and function of the brain relate to cognition and behaviour.[citation needed]

A neurocognitive deficit is a reduction or impairment of cognitive function in one of these areas, but particularly when physical changes can be seen to have occurred in the brain, such as aging related physiological changes or after neurological illness, mental illness, drug use, or brain injury.[1][2]

A clinical neuropsychologist may specialise in using neuropsychological tests to detect and understand such deficits, and may be involved in the rehabilitation of an affected person. The discipline that studies neurocognitive deficits to infer normal psychological function is called cognitive neuropsychology.

Etymology

[edit]The term neurocognitive is a recent addition to the nosology of clinical Psychiatry and Psychology. It was rarely used before the publication of the DSM-5, which updated the psychiatric classification of disorders listed in the "Delirium, Dementia, and Amnestic and Other Cognitive Disorders" chapter of the DSM-IV.[3] Following the 2013 publication of the DSM-5, the use of the term "neurocognitive" − increased steadily.[4]

Adding the prefix "neuro-" to the word "cognitive" is an example of pleonasm because analogous to expressions like "burning fire" and "black darkness", the prefix "neuro-" adds no further useful information to the term "cognitive". In the field of clinical neurology, clinicians continue using the simpler term "cognitive", due to the absence of evidence for human cognitive processes that do not involve the nervous system.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Cognition

- Cognitive neuropsychology

- Cognitive neuroscience

- Cognitive rehabilitation therapy

- Neurology

- Neuropsychology

- Neuropsychological test

- Neurotoxic

- Brain fog

- Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder

- Depersonalization

- Dementia

- Mild cognitive impairment

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Concussions in sport

References

[edit]- ^ Blazer, Dan (2013). "Commentary: Neurocognitive Disorders in DSM-5". American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (6): 585–587. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020179. PMID 23732964.

- ^ Torres, Callie (Oct 21, 2020). "Brain Fog - What are the symptoms, causes, treatments, and COVID 19 medical effects on brain health?". University of Medicine and Health Sciences in St. Kitts. Archived from the original on Oct 1, 2023.

- ^ Sachdev, PS; Blacker, D; Blazer, DG; Ganguli, M; Jeste, DV; Paulsen, JS; et al. (2014). "Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach" (PDF). Nat Rev Neurol. 10 (11): 634–42. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.181. PMID 25266297. S2CID 20635070.

- ^ "neurocognitive, dsm-5". Google Trends. Archived from the original on 30 Mar 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Green, K. J. (1998). Schizophrenia from a Neurocognitive Perspective. Boston, Allyn and Bacon.