Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nheengatu language

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Nheengatu | |

|---|---|

| Modern Tupi, Amazonic Tupi | |

| Native to | Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela |

Native speakers | <10,000 (2025)[1] |

Tupian

| |

Early form | |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | São Gabriel da Cachoeira and Monsenhor Tabosa |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:yrl – Nhengatu [sic]kgm – Karipúna (retired) |

| Glottolog | nhen1239 |

| ELP | Nheengatú |

| |

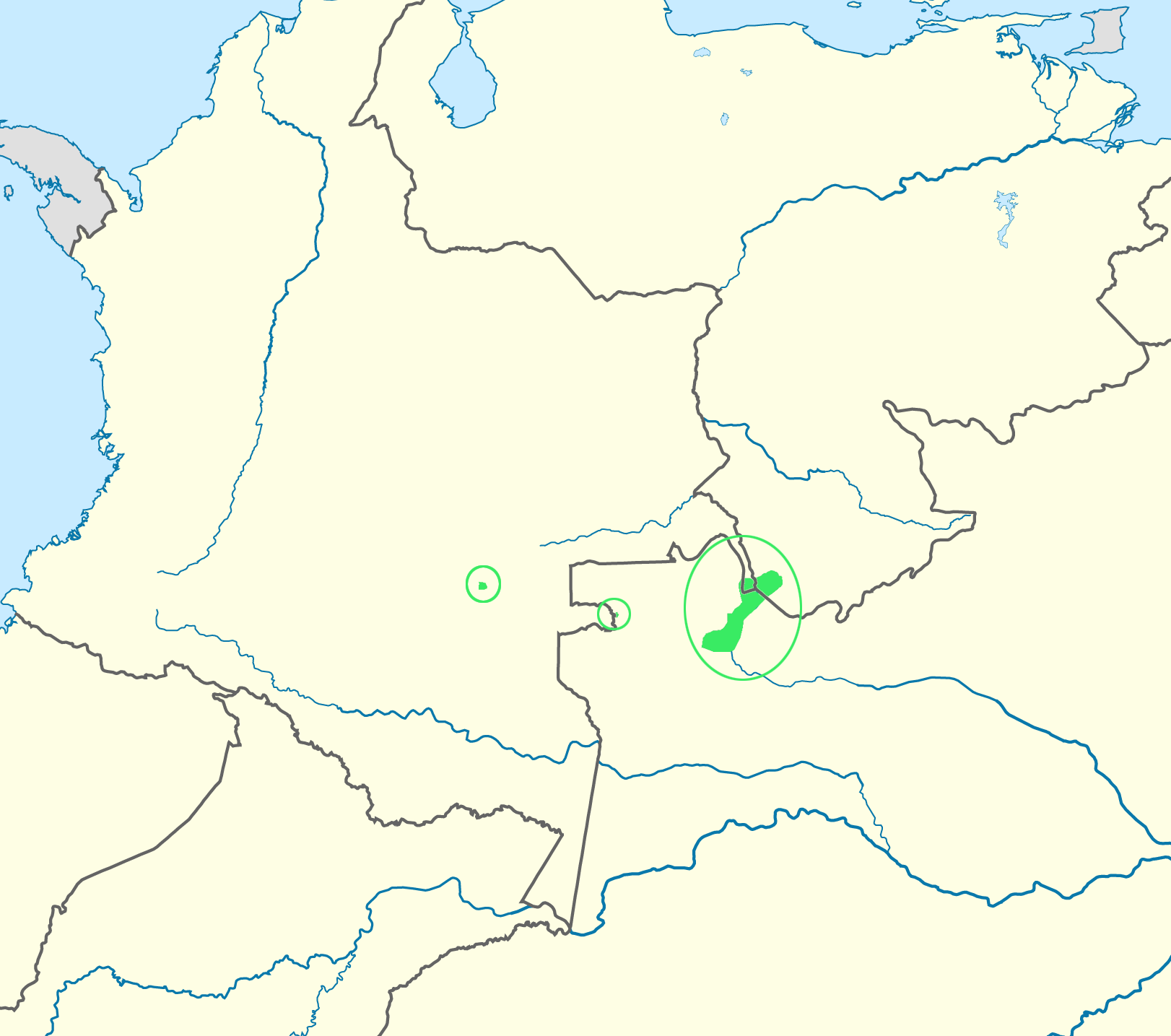

Nheengatu, also known as Modern Tupi[2] and Amazonic Tupi,[3] is a Tupi–Guarani language. It is spoken throughout the Rio Negro region among the Baniwa, Baré and Warekena peoples, mainly in the municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira and the state of Amazonas, Brazil.

Since 2002, it has been one of Amazonas's official languages,[4] along with Apurinã, Baniwa, Dessana, Kanamari, Marubo, Matis, Matses, Mawe, Mura, Tariana, Tikuna, Tukano, Waiwai, Waimiri, Yanomami, and Portuguese.[5] Outside of the Rio Negro region, the Nheengatu language has more dispersed speakers in the Baixo Amazonas region (in the state of Amazonas) among the Sateré-Mawé, Maraguá and Mura people. In the Baixo Tapajós and the state of Pará, it is being revitalized by the people of the region, such as the Borari and the Tupinambá,[6] and also among the riverside dwellers themselves.

According to Ethnologue, a 2005 study—not available on its website—estimated the number of Nheengatu speakers at around 19,600, though this figure is subject to debate. In 2025,[update] University of São Paulo (USP) professor Thomas Finbow estimated between 5,000 and 7,000 speakers in Brazil, and fewer than 10,000 globally including communities in Venezuela and Colombia.[1] Nheengatu is considered significant for the study of language change as one of the few Indigenous languages with a long documented history.[1] It is considered the most historically significant among the minority languages still spoken in Brazil.[7]

Glottonym

[edit]The language name derives from the words nhẽẽga (meaning "language" or "word") and katu (meaning "good").[3][8] Nheengatu is referred to by a wide variety of names in literature, including Nhengatu, Tupi Costeiro, Geral, Yeral (in Venezuela), Tupi Moderno,[9]: 13 Nyengato, Nyengatú, Waengatu, Neegatú, Is'engatu, Língua Brasílica, Tupi Amazônico[3], Ñe'engatú, Nhangatu, Inhangatu, Nenhengatu,[8] Yẽgatú, Nyenngatú, Tupi, and Lingua Geral. It is also commonly referred to as the Língua Geral Amazônica (LGA) in Brazil.

Classification

[edit]Nheengatu developed from the extinct Tupinamba language and belongs to the Tupi–Guarani branch of the Tupi language family.[10] The Tupi–Guarani language family is a large and diverse group of languages, including, for example, Xeta, Siriono, Arawete, Kaapor, Kamayura, Guaja, and Tapirape. Many of these languages differed years before the invasion of Portuguese colonizers to the territory now known as Brazil. Over time, the term "Tupinamba" was used to describe groups that were "linguistically and culturally related.”

Taking personal pronouns as an example, see a comparison between Brazilian Portuguese, Old Tupi, and Nheengatu:

| Portuguese | Ancient Tupi | Yẽgatu (Nheengatu from Rio Negro) |

Traditional Nheengatu |

Tapajoawaran Nheengatu | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | singular | eu | xe, ixé | se, ixé | çe, ixé | se, ixé | |

| plural | exclusive | nós | oré | ||||

| inclusive | îandé | yãné, yãdé | yãné, yãdé | yãné, yãdé | |||

| 2nd person | singular | tu | ne/nde, endé | ne, ῖdé | ne, ῖdé | ne, ῖdé | |

| plural | vós | pe, peẽ | pe, pẽye | pe, pẽnhé | pe, penhẽ | ||

| 3rd person | singular | ele, ela | i, a'e | i, ae | i, aé | i, aé | |

| plural | eles, elas | i, a'e | i/ta, aῖta | aῖtá | i/ta, aῖta | ||

Eduardo de Almeida Navarro, a Brazilian philologist specialized in Nheengatu, argues that with its current characteristics, Nheengatu would only have emerged in the 19th century, as a natural evolution of the Northern General Language (NGL).

Comparisons between Tupi, Portuguese, and Nheengatu variants:

| English | Portuguese | Ancient Tupi | Yẽgatu (Nheengatu from Rio Negro) |

Traditional Nheengatu | Tapajoawaran Nheengatu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bird | pássaro | gûyrá | wira | wirá | wirá |

| man | homem | abá | apiawawa | apigá | apigá |

| woman | mulher | kunhã | kuyã | kunhã | kunhã |

| happiness | alegria | toryba | surisa | çuriçawa | surisawa |

| city | cidade | tabusu | tawasu | mairí | tawasú |

| hammock | rede | iny | makira | makira, gapõna | makina |

| water | água | 'y | ii | yy | i |

In addition to the previously mentioned general language of São Paulo, now extinct, Nheengatu is closely related to ancient Tupi, an extinct language, and to Guarani of Paraguay, which, far from being extinct, is the most spoken language in the country and one of its official languages. According to some sources,[which?] ancient Nheengatu and Guarani were mutually intelligible.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Belonging to the Tupi-Guarani linguistic family, Nheengatu emerged in the 18th century, descending from the now-extinct Amazonian Tupinambá, a regional Tupi variant that originated in the Odisseia Tupínambá. The exodus of that nation, fleeing from Portuguese invaders on the Bahia coast, entered the Amazon and settled first in Maranhão, and from there to the bay of Guajará (Belém), the mouth of the Tapajós river, to the Tupinambarana island (Parintins), between the borders of Pará and Amazonas. The language of the Tupinambás then, as it belongs to a feared and conquering people, became a lingua franca, which in contact with the conquered languages gained its differentiation, hence why the Arawak peoples of the Parintins region came to be called Tupinambaranas, among them, the maraguazes, the çapupés, the curiatós, the Parintins and the Sateré-Mawé themselves.

Already with the Amazon conquered by the Portuguese, a fact that occurred from 1600, and having established a colony at the beginning of the 17th century, the so-called state of Grão-Pará and Maranhão, whose capital Belém was named Cidade dos Tupinambás or Tupinãbá marií, Franciscan and Jesuit priests, aiming at catechism using that language, elaborated the grammar and their orthography, although Latinized, which resulted in the Northern General Language, or General Amazonian Language, (a name still used today), whose development took place parallel to that of São Paulo general language (extinct). Since then, Nheengatu has spread throughout the Amazon as an instrument of colonization, Portuguese domain and linguistic standardization, where many peoples started to have it as their main language at the expense of their own, as well as peoples like the Hanera, better known as Baré, who became Nheengatu speakers, which led to the extinction of their native language. The Maraguá people, themselves historical speakers of Nheengatu, recently sought to revitalize their own language; today they learn Maraguá alongside Nheengatu in local schools.

The number of speakers of other languages vastly outnumbered the Portuguese settlers in the Amazon, so much so that the Portuguese themselves adapted to the native language. "To speak or converse in the colony of Grão Pará, I had to use Nheengatu; if not, I would be talking to myself, since no one used Portuguese, except in the government palace in Belém and among the Portuguese themselves."[11][4]

The General Language was established as the official language from 1689 to 1727 in the Amazon (Grão Pará and Maranhão), but with the aim of deculturating the Amazon people, the Portuguese language was promoted, but without success. In the mid-18th century, the Amazon General Language (distinct from the São Paulo General Language, a similar variety used further south) was used throughout the colony. At this point, Tupinambá remained intact, but as a "liturgical language". The languages used in everyday life evolved drastically over the century due to contact with the language, with Tupinambá as the “language of rituals, and Amazonian General Language, the language of popular communication and therefore of religious instruction." Moore (2014) notes that by the mid-18th century, the Amazon and Tupinambá General Languages were already distinct. Until then, the original Tupinambá community was facing a decline, but other speaking communities were still required by Portuguese missionaries to learn the Tupinambá language. Efforts to communicate between communities resulted in the "corruption" of the Tupinambá language, hence the distinction between Tupinambá and the Amazonian general language.

Nheengatu continued to evolve as it expanded into the Alto Rio Negro region. There was contact with other languages such as Marawá, Baníwa, Warekana, Tucano, and Dâw (Cabalzar; Ricardo 2006 in Cruz 2015).

The General Language evolved into two branches, the Northern General Language (Amazonian) and the Southern General Language (Paulista), which at its height became the dominant language of the vast Brazilian territory.

An anonymous manuscript from the 18th century is emblematically titled "Dictionary of the general language of Brazil, spoken in all the towns, places, and villages of this vast State, written in the city of Pará, year 1771".

If Nheengatu was the major obstacle for the cultural and linguistic domination of Portuguese in the region, the colonizers saw that it was necessary to take it away from the people and impose the Portuguese language, which at first was not successful since the general language was very well rooted both among indigenous people and in the speech of blacks and whites themselves. The language had its first ban on the part of the Portuguese government, during the administration of the Marquis of Pombal, who intended to impose the Portuguese language in the Amazon and make the names of places Portuguese. Hence, many places have their names changed from nheengatu to names of places and cities in Portugal, thus appearing names that today make up Amazonian municipalities such as Santarém, Aveiro, Barcelos, Belém, Óbidos, Faro, Alenquer, and Moz.

With the independence of Brazil in 1822, even though Grão-Pará (Amazon) is a separate Portuguese colony, its local rulers decided to integrate into the new country, which greatly displeased the inhabitants of indigenous origin, who were the majority of the people in general, This later led the Amazon to an independence revolution that lasted for 10 years.

The second ban on the language came right after this revolution, better known as Cabanagem or War of the Cabanos, and when the rebels were defeated (1860), the Brazilian government imposed a harsh persecution of the speakers of Nheengatu. Half of the male population of Grão-Pará (Amazon) was murdered and anyone who was caught speaking in Nheengatu was punished and if they were not contacted indigenous, they were baptized by priests and received their surnames on certificates, since the priests themselves were their godparents, this resulted in people of indigenous origin with Portuguese surnames without even being heirs to colonists. The imposition of the Portuguese language this time had an effect and with the advent of Portuguese schools, the population was shepherded to the new language.

Also in the 20th century, economic and political events like the Amazon Rubber Boom, which brought huge waves of government encouraged settlers from the Northeast to the Amazon, led to an increased Portuguese presence. This again forced indigenous peoples to move or be subjected to forced labor. The language was again influenced by the increased presence of Portuguese speakers.

Nheengatu remained mainly among the most distant inhabitants of the urban centers, in the families descended from the cabanos and among unconquered peoples. Furthermore, "tapuios" (ribeirinhos) kept their accent and part of their speech tied to their language. Until 1920 it was common for Nheengatu to be used in traditional commercial centers in Manaus, Santarém, Parintins, and Belém.

Current use

[edit]Nheengatu is spoken in the Alto Rio Negro region, in the state of Amazonas, in the Brazilian Amazon and in neighboring parts of Colombia and Venezuela. There are potentially as many as 19,000 Nheengatu speakers worldwide, according to Ethnologue (2005),[12] although some journalists have reported as many as 30,000.[13][14] Currently, it is still spoken by around 73.31% of the 29,900 inhabitants of São Gabriel da Cachoeira (IBGE 2000 Census), around 3,000 people in Colombia, and around 2,000 people in Venezuela, especially in Rio Negro river basin (Uaupés and Içana rivers).[12] Furthermore, it is the native language of the rural caboclo population of the area and is a common language of communication between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, or between Indigenous peoples of different languages. It is also an instrument of ethnic affirmation of Amazonian indigenous peoples who have lost their native languages, such as Barés, Arapaços, Baniuas, Uarequenas, and others.

Ethnologue rates Nheengatu as "changing" with a rating of 7 on the Gradual Intergenerational Interruption Scale (GIDS) (Simons and Fennig 2017). According to this scale, this classification suggests that "the population of children may use the language among themselves, but it is not being transmitted to children". According to the UNESCO Atlas of Endangered Languages of the World, Nheengatu is classified as "severely endangered".[15] The language has recently regained some recognition and prominence after being suppressed for many years.

In December 2002, Nheengatu gained official language status alongside Portuguese in the municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira in accordance with local law 145/2002.[3] Now Nheengatu is one of the four official languages of the municipality.[16]

In 1998, University of São Paulo professor Eduardo de Almeida Navarro founded the Tupi Aqui organization dedicated to promoting the teaching of historical Tupi and Nheengatu in high schools in São Paulo and elsewhere in Brazil.[3] Professor Navarro wrote a textbook for teaching Nheengatu that Tupi Aqui makes available, along with other teaching materials, on a website hosted by the University of São Paulo.[17]

Revitalization efforts

[edit]In 2007, USP established the first Brazilian university chair dedicated to the study of Nheengatu. In 2012, the language was incorporated into the graduate program in translation studies. Consequently, in 2016 Graciliano Ramos's A terra dos meninos pelados was translated into Nheengatu.[18] Translations contribute to lexical revitalization; this translation of Ramos's work included linguistic and lexical research on Nheengatu, allowing for the use of obsolete words remembered only by the elders or already completely forgotten and replaced by borrowings from Portuguese,[19] although borrowings adopted more than a century ago—now fully integrated into the language's tradition—were also employed.[20] In 2017, The Little Prince was also translated as part of a master's dissertation supervised by USP professor Eduardo de Almeida Navarro. Likewise, in many instances the translation employed equivalent terms, adaptations, neologisms, and the revival of archaic words; for example, the tiger was replaced with yawareté-pinima (jaguar) and wheat with awatí (corn), and the very title revived an old expression which served "to connect a word that had fallen out of use with the naming of a character in the book who was mysterious and little known".[21]

In 2021, "Nheengatu App" was launched, becoming the first application for teaching an Indigenous language in Brazil. It teaches the Tapajoara variant of the language.[22] Its release was supported by the Aldir Blanc Law and the Secretariat of Culture of Pará.[22][23][24] According to its creator Suellen Tobler, the app was used in Indigenous schools in the Lower Tapajós region, and by September 2023 approximately 2,200 users had registered.[22] In March 2024, the project was presented at Campus Party Brasília.[22][24] Other Brazilian Indigenous groups showed interest in the initiative, and Tobler went on to co-author two other apps for teaching native Brazilian languages.[24]

In 2023, the Brazilian Constitution was translated into Nheengatu, marking the first time it was rendered into an Indigenous language—until then, it had been translated only into Spanish and English.[25][26][27] The translation was carried out by 15 bilingual Indigenous individuals from the Upper Negro River and Middle Tapajós regions,[a] through a project sponsored by the Supreme Federal Court (STF) and the National Council of Justice, within the framework of the United Nations's International Decade of Indigenous Languages.[25][27] They worked for at least three hours a day over the course of three months; project curator and then National Library president Marco Lucchesi stated the work was intense with specialists available around the clock to answer any questions.[28] Then STF president Rosa Weber attended the launch event in São Gabriel da Cachoeira[b] and stated Nheengatu was chosen because of its significance to the Amazon region.[27] Later, Weber presented a copy to Lucchesi at the National Library, the first time in 100 years that a head of the judiciary had visited it.[26][29]

Existing literature

[edit]Over the course of its evolution since its beginnings as Tupinambá, extensive research has been done on Nheengatu. There have been studies done at each phase of its evolution, but much has been focused on how aspects of Nheengatu, such as its grammar or phonology, have changed upon contact over the years. (Facundes et al. 1994 and Rodrigues 1958, 1986).

As mentioned earlier, the first documents that were produced were by Jesuit missionaries in the 16th and 17th centuries, such as Arte da Grammatica da Lingoa mais usada na costa do Brasil by Father José de Anchieta (1595) and Arte da Língua Brasilíca by Luis Figueira (1621). These were detailed grammars that served their religious purposes. Multiple dictionaries have also been written over the years (Mello 1967, Grenand and Epaminondas 1989, Barbosa 1951). More recently, Stradelli (2014) also published a Portuguese-Nheengatu dictionary.

There have also been several linguistic studies of Nheengatu more recently, such as Borges (1991)’s thesis on Nheengatu phonology and Cruz (2011)’s detailed paper on the phonology and grammar of Nheengatu. She also studied the rise of number agreement in modern Nheengatu, by analyzing how grammaticalization occurred over the course of its evolution from Tupinambá (Cruz 2015). Cruz (2014) also studies reduplication in Nheengatu in detail, as well as morphological fission in bitransitive constructions. A proper textbook for the conducting of Nheengatu classes has also been written.[17] Lima and Sirvana (2017) provides a sociolinguistic study of Nheengatu in the Pisasu Sarusawa community of the Baré people, in Manaus, Amazonas.

In 2023, the Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil (Brazilian Constitution) promulgated in 1988, was translated into Nheengatu for the first time.[30]

Language documentation projects

[edit]Language documentation agencies (such as SOAS, Museu do Índio, Museu Goeldi and Dobes) are currently not engaged in any language documentation project for Nheengatu. However, research on Nheengatu by Moore (1994) was supported by Museu Goeldi and the Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq), and funded by the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas (SSILA) and the Inter-American Foundation. In this study, Moore focused on the effects of language contact, and how Nheengatu evolved over the years with the help of a Nheengatu-speaking informant. Moore (2014) urges for the "location and documentation of modern dialects of Nheengatu", due to their risk of becoming extinct.[10]

Ethnography

[edit]Anthropological research has been done on the changing cultural landscapes along the Amazon, as well as life of the Tupinambá people and their interactions with the Jesuits.[31] Floyd (2007) describes how populations navigate between their "traditional" and "acculturated" spheres.[32] Other studies have focused on the impact of urbanization on Indigenous populations in the Amazon (de Oliveira 2001).

Phonology

[edit]Consonants

[edit]Parentheses mark marginal phonemes occurring only in few words, or with otherwise unclear status.[10]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lab. | ||||||||

| Plosive | plain | p | t | (tʃ) | k | kʷ | (ʔ) | ||

| voiced | (b) | (ɡ) | |||||||

| prenasal | ᵐb | ⁿd | ᵑɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | s | ʃ | |||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

| Approximant | w | j | j̃ | ||||||

Vowels

[edit]| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ĩ | u ũ | |

| Mid | e ẽ | o õ | |

| Open | a ã |

Morphology

[edit]There are eight word classes in Nheengatu: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, postpositions, pronouns, demonstratives, and particles.[10] These eight word classes are also reflected in Cruz (2011)’s Fonologia e Gramática do Nheengatú. In her books, Cruz includes 5 chapters in the Morphology section that describes lexical classes, nominal, and verbal lexicogenesis, the structure of the noun phrase and grammatical structures. In the section on lexical classes, Cruz discusses personal pronominal prefixes, nouns, and their subclasses (including personal, anaphoric, and demonstrative pronouns as well as relative nouns), verbs and their subclasses (such as stative, transitive, and intransitive verbs), and adverbial expressions. The subsequent chapter on nominal lexicogenesis discusses endocentric derivation, nominalization, and nominal composition. Under verbal lexicogenesis in Chapter 7, Cruz covers valency, reduplication, and the borrowing of loanwords from Portuguese. The following chapter then discusses the distinction between particles and clitics, including examples and properties of each grammatical structure.

Pronouns

[edit]There are two types of pronouns in Nheengatu: personal or interrogative. Nheengatu follows the same pattern as Tupinambá, in that the same set of personal pronouns is adopted for the subject and object of a verb.[10]

| Singular | Sg Prefix | Plural | Pl Prefix | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | isé | se- | yãndé | yane- |

| 2 | ĩndé | ne- | pẽỹẽ | pe- |

| 3 | aʔé | i- s- |

aẽtá | ta- |

Examples of Personal Pronouns in use:

inde

2SG

re-kuntai

2sgA-speak

amu

other.entity

nheenga

language

"You speak another language."

isé

1SG

se-ruri

1sgE-be.happy

a-iku.

1sgA.be

"I am happy."

As observed in Table 3, in Nheengatu, personal pronouns can also take the form of prefixes. These prefixes are necessary in the usage of verbs as well as postpositions. In the latter case, free forms of the pronouns are not permitted.[10] Moore illustrates this with the following:

i)

se-irũ

1SG(prefix)-with

‘with me’

ii)

*isé-irũ

1SG-with

‘with me’

The free form of the first person singular pronoun cannot be combined with the postposition word for 'with'.

The second set of pronouns are interrogative, and are used in question words.

| mãʔã | 'what, who, whom' | ||

| awá | 'who, whom' |

Verbal affixes

[edit]According to Moore (2014), throughout the evolution of Nheengatu, processes such as compounding were greatly reduced. Moore cites a summary by Rodrigues (1986), stating that Nheegatu lost Tupinambá's system of five moods (indicative, imperative, gerund, circumstantial, and subjunctive), converging into a single indicative mood. Despite such changes alongside influences from Portuguese, however, derivational, and inflectional affixation was still intact from Tupinambá. A select number of modern affixes arose via grammaticization of what used to be lexical items. For example, Moore (2014) provides the example of the former lexical item etá 'many'. Over time and grammaticization, this word became to plural suffix -itá.[10]

Apart from the pronominal prefixes shown in Table (3), there are also verbal prefixes.[10] Verbs in Nheengatu fall into three mutually exclusive categories: intransitive, transitive, and stative. By attaching verbal prefixes to these verbs, a sentence can be considered well-formed.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | a- | ya- |

| 2 | re- | pe- |

| 3 | u- | aẽtá-ú |

Examples of verbal prefixes:

i)

a-puraki

1sg-work

‘I work.’

ii)

a-mũỹã

1sg-make

I make (an object).’

In these examples from Moore (2014), the verbal first person singular prefix a- is added to the intransitive verb for 'work' and transitive verb for 'make' respective. Only when prefixed with this verbal clitic, can they be considered well-formed sentences.[10]

Reduplication

[edit]Another interesting morphological feature of Nheengatu is reduplication, which Cruz (2011) explains in her grammar to employed differently based on the community of Nheengatu speakers. This is a morphological process that was originally present in Tupinambá, and it tends to be used to indicate a repeated action.[10]

u-tuka~tuka

3SG-REDUP~knock

ukena

door

"He is knocking on the door (repeatedly)."

In this example, the reduplicated segment is tuka, which is the Nheengatu verb for 'knock'. This surfaces as a fully reduplicated segment. However, partial reduplication also occurs in this language. In the following example elicited by Cruz, the speaker reduplicates the first two syllables (a CVCV sequence) of the stem word.

Apiga

men

ita

PL

sasi~sasiara.

REDUP~BE.sad

"The men are sad."

Another point to note from the above example is the usage of the plural word ita. Cruz (2011) highlights that there is a distinction in the usage of reduplication between communities. The speakers of Içana and the upper region of the Rio Negro use Nheengatu as their main language, and reduplication occurs in the stative verbs, expressing intensity of a property, and the plural word ita doesn't necessarily need to be used. On the other hand, in Santa Isabel do Rio Negro and the more urban area of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, speakers tend to be bilingual, with Portuguese used as the main language. In this context, these speakers also employ reduplication to indicate the intensity of a property, but the plural ita must be used if the subject is plural.

Sample texts

[edit]- Pedro Luiz Sympson (1876)

- A! xé ánga, hu emoté i Iára. / Xé abú iu hu rori ána Tupã recé xá ceiépi. / Maá recé hu senú i miaçúa suhi apipe abasáua: / ahé recé upáem miraitá hu senecáre iché aié pepasáua. / Maá recé Tupã hu munha iché áramau páem maá turuçusáua, / i r'ira puranga eté. / Y ahé icatusáua xé hu muçaim ramé, r'ira péaca upáem r'iapéaca ramé, maá haé aitá hu sequéié.

- Pe. Afonso Casanovas (2006)

- Aikwé paá yepé tetama puranga waá yepé ipawa wasú rimbiwa upé. Kwa paá, wakaraitá retama. Muíri akayú, paá, kurasí ara ramé, kwá uakaraitá aywã ta usú tawatá apekatú rupí. Muíri viaje, tausú rundé, aintá aría waimí uyupuí aitá piripiriaka suikiri waá irũ, ti arã tausaã yumasí tauwatá pukusawa.

- Eduardo de Almeida Navarro (2011)

- 1910 ramé, mairamé aé uriku 23 akaiú, aé uiupiru ana uuatá-uatá Amazônia rupi, upitá mími musapíri akaiú pukusaua. Aé ukunheséri ana siía mira upurungitá uaá nheengatu, asuí aé umunhã nheengarisaua-itá marandua-itá irũmu Barbosa Rodrigues umupinima ana uaá Poranduba Amazonense resé.

- Aline da Cruz (2011)

- A partir di kui te, penhe nunka mais pesu pekuntai aitekua yane nheenga. Yande kuri, mira ita, yasu yakuntai. Ixe kuri asu akuntai perupi. Ixe kua mira. Ixe asu akuntai perupi. Penhe kuri tiã pesu pekuntai. Pepuderi kuri penheengari yalegrairã yane felisidaderã.

- Sample from book Yasú Yapurũgitá Yẽgatú (2014)

- Se mãya uyutima nãnã kupixawa upé. Nãnã purãga yaú arama yawẽtu asuí purãga mĩgaú arama yuiri. Aikué siya nãnã nũgaraita. Purãga usemu mamé iwí yumunaniwa praya irũmu.

- Roger Manuel López Yusuino (Venezuelan Nheengatu) (2013)

- Tukana aé yepé virá purangava asoi orikú bando ipinima sava, ogustari oyengari kuemaite asoi osemo ara ramé osikari arama ombaó vasaí iyá. Tukana yepé virá porangava yambaó arama asoi avasemo aé kaáope asoi garapé rimbiva ropí.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Including Dadá Baniwa, Edson Baré, Edilson Martins Baniwa, Melvino Fontes Olímpio, Sidinha Gonçalves Tomas, Dime Pompilho Liberato, Gedeão Arapyú, Frank Bitencourt Fontes, Francisco Cirineu Martins, George Borari, and Cauã Borari.[25]

- ^ As well as other prominent authorities, namely Sonia Guajajara, Cármen Lúcia, Joenia Wapichana, Lelio Bentes Corrêa, Marco Lucchesi, and José Ribamar Bessa Freire.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Quinto, Antonio Carlos (22 August 2025). "Projeto baseado em IA atua na preservação da língua indígena nheengatu, no Alto Rio Negro, no Amazonas" [AI-based project works on the preservation of the Indigenous Nheengatu language in the Upper Rio Negro, in Amazonas]. Jornal da USP (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 26 August 2025. Retrieved 12 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Alves, Ozias Jr. (2010). ""Ñe'engatu" em guarani significa "falar demais" ou alguém que fala demais". Parlons Nheengatu: Une langue tupi du Brésil. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-13259-7.

- ^ a b FREIRE, José Ribamar Bessa (2011). A história das línguas na Amazônia (in Portuguese) (2 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: EDUERJ: Rio Babel.

- ^ "Amazonas state now has 17 official languages". Agência Brasil. 21 July 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2025.

- ^ Jesus, Hudson Romário Melo de (31 January 2022). "Yâdé Kiirîbawa Yepé Wasú! Uma reflexão sobre a luta Tupinambá em defesa de seu território". Revista Arqueologia Pública (in Portuguese). 17: e022001. doi:10.20396/rap.v17i00.8666579. ISSN 2237-8294. S2CID 248760708.

- ^ a b FERREIRA, A. B. H. (1986). Novo dicionário da língua portuguesa (2 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Moore, Facundes & Pires 1994.

- ^ Rodrigues 1996.

- ^ a b "Nhengatu". Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (28 August 2005). "Language Born of Colonialism Thrives Again in Amazon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015.

- ^ "A língua do Brasil". Super (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Moseley, Christopher; Nicolas, Alexandre (2010). Atlas of the world's languages in danger. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. p. 17. ISBN 978-92-3-104096-2.

- ^ "Novo em Folha - Línguas ameaçadas de extinção no Brasil - São Gabriel…". archive.md. 4 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Ferreira, Ivanir (19 April 2017). ""O Pequeno Príncipe" ganha tradução para o tupi" ["The Little Prince" receives a translation into Tupi]. Jornal da USP (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 21 January 2025. Retrieved 13 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d Yamaguti, Bruna (31 March 2023). "'Nheengatu App': conheça o 1º aplicativo voltado para o ensino de língua indígena no Brasil" ['Nheengatu App': meet the 1st application aimed at teaching an indigenous language in Brazil]. g1 (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 24 January 2025. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ Jansen, Roberta (20 January 2022). "Academia quer reviver o nheengatu, a língua perdida dos indígenas da Amazônia" [Academy wants to revive Nheengatu, the lost language of the indigenous people of the Amazon]. Estadão (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 19 May 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ a b c Costa, Lara (14 April 2024). "Futuro ancestral: desenvolvedora cria app que ensina língua indígena do Brasil" [Ancestral future: developer creates app that teaches an indigenous language of Brazil]. Correio Braziliense (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 28 March 2025. Retrieved 15 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Funai participa do lançamento histórico da Constituição Federal na língua indígena Nheengatu" [Funai participates in the historic launch of the Federal Constitution in the Nheengatu Indigenous language]. Fundação Nacional dos Povos Indígenas (in Portuguese). 19 July 2023. Archived from the original on 3 April 2025. Retrieved 13 October 2025.

- ^ a b Gandra, Alana (25 August 2023). "Biblioteca Nacional recebe Constituição de 1988 em nheengatu" [National Library receives 1988 Constitution in Nheengatu]. Agência Brasil (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 7 December 2024. Retrieved 12 October 2025.

- ^ a b c León, Lucas Pordeus (19 July 2023). "Constituição brasileira é traduzida pela 1ª vez para língua indígena" [Brazilian Constitution is translated for the 1st time into an Indigenous language]. Agência Brasil (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 18 July 2025. Retrieved 13 October 2025.

- ^ Serra, Paolla (17 July 2023). "Constituição Federal ganha versão em nheengatu, língua indígena que vem do tupi antigo" [Federal Constitution gains version in Nheengatu, an indigenous language that comes from Old Tupi]. O GLOBO (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 31 July 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "Presidente do STF entrega exemplar da Constituição traduzida para o Nheengatu à Biblioteca Nacional" [President of the STF delivers a copy of the Constitution translated into Nheengatu to the National Library]. Supremo Tribunal Federal (in Portuguese). 25 August 2023. Archived from the original on 13 October 2025. Retrieved 13 October 2025.

- ^ Mundu Sa Turusu Waá : Ubêuwa Mayé Míra Itá Uikú Arãma Purãga Iké Braziu Upé (in Portuguese and Nheengatu). Supremo Tribunal Federal, Conselho Nacional de Justiça. 2023. ISBN 978-65-5972-113-9.

- ^ Forsyth, Donald W (1978). The Beginning of Brazilian Anthropology: Jesuits and Tupinamba Cannibalism. Journal of Anthropological Research.

- ^ Floyd, Simeon (2007). Changing Times and Local Terms on the Rio Negro, Brazil: Amazonian Ways of Depolarizing Epistemology, Chronology and Cultural Change. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies.

Bibliography

[edit]- Navarro, Eduardo de Almeida; Ávila, Marcel Twardowsky; Trevisan, Rodrigo Godinho (2017). "O Nheengatu entre a vida e a morte: a tradução literária como possível instrumento de sua revitalização lexical" [Nheengatu between life and death: literary translation as a possible instrument of its lexical revitalization]. Revista Letras Raras (in Portuguese). 6 (2). doi:10.35572/rlr.v6i2.768. ISSN 2317-2347. Archived from the original on 21 January 2025. Retrieved 14 October 2025.

- Moore, Denny; Facundes, Sidney; Pires, Nádia (1994). Nheengatu (Língua Geral Amazônica), its History, and the Effects of Language Contact (PDF). Survey of California and Other Indian Languages. Berkeley: University of California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2017.

- Rodrigues, Aryon (1996). "As línguas gerais sul-americanas". Papia. 4 (2 ed.). Etnolinguística: 6–18.

- Navarro, Eduardo De Almeida (2005). Método moderno de tupi antigo: a língua do Brasil dos primeiros séculos (in Portuguese) (3 ed.). São Paulo: Global.

- Navarro, Eduardo De Almeida (2011). Curso de Língua Geral (Nheengatu ou Tupi Moderno) a língua das origens da civilização Amazônica (PDF) (in Portuguese) (1 ed.). São Paulo. ISBN 978-85-912620-0-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - da Cruz, Aline (2011), Fonologia e Gramática do Nheengatú: A língua geral falada pelos povos Baré, Warekena e Baniwa (PDF) (in Portuguese), Lot Publications, ISBN 978-94-6093-063-8, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2014

- Lima Schwade, Michéli Carolíni de Deus (2014), Descrição Fonético-Fonológica do Nheengatu Falado no Médio Rio Amazonas (PDF), Manaus: Federal University of Amazonas

External links

[edit]- Silva, Beto (2021), Nativos digitais, ISTOÉ Dinheiro.

- "Luso-brazilian documentary film called "Nheengatu", it shows indigenous and native speak Nheengatu in daily life"..

- Nhengatu, Archive.

- "Pres.casa-lllegues". Gencat. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- "Nheengatu". Brazil: INPA — Núcleo de Pesquisas em Ciências Humanas e Sociais. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2006..

- "Nheengatu e dialeto caipira". Sosaci. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2006..

- "Amazon", The New York Times, 28 August 2005.

- Playlist with video classes by Prof Eduardo Navarro and support material in PDF in the description of the playlist

- Website of Jehovah's Witnesses in Nheengatu, with texts, videos and audios

Nheengatu language

View on GrokipediaNomenclature and Etymology

Alternative Names and Variants

Nheengatu is historically referred to as Língua Geral Amazônica, a term distinguishing the northern Amazonian variety from the southern Língua Geral Paulista, reflecting its role as a regional lingua franca among indigenous groups and settlers since the 18th century.[6] It is also known as Modern Tupi or Amazonic Tupi, emphasizing its descent from colonial-era Tupi varieties while acknowledging phonological and lexical shifts that differentiate it from extinct coastal forms.[7] In Venezuela, particularly among communities along the border with Brazil, the language is called Yeral, spoken by approximately 2,000 individuals as of 2010 estimates, often in multilingual settings with Arawakan tongues.[4] The language features regional variants, with the predominant form in the upper Rio Negro basin—spoken by groups like the Baniwa, Baré, and Warekena—characterized by specific phonetic traits such as nasalization patterns and vocabulary influenced by local Arawakan substrates.[8] In contrast, the variant along the middle Solimões River shares similarities with the Rio Negro form but exhibits minor lexical differences tied to riverine trade networks. Further south, in the Purus River region, the Tapajoara dialect prevails among groups like the Arapium, featuring distinct morphological elements and serving as a basis for contemporary revitalization efforts, including educational materials.[9] These variants, while mutually intelligible, reflect substrate influences from local indigenous languages, with the Rio Negro form showing heavier Arawakan borrowing compared to the more conservative Purus variants; however, no standardized dialectal boundaries exist due to historical mobility and inter-ethnic contact.[1]Derivation of the Term

The term Nheengatu is a compound formed from the Tupi-Guarani morphemes nheen (or nhe'en), denoting "to speak" or "language," and katu, signifying "good" or "fine," yielding the literal meaning "good language" or "fine speaking."[10][11] This etymology was first documented by the Brazilian naturalist Couto de Magalhães in 1876, who coined the term to describe the Amazonian variety of Lingua Geral, distinguishing it from coastal forms.[10] Among speakers, Nheengatu functions as an endogenous self-designation, embodying a cultural valuation of the language as an effective and polished medium for interethnic exchange, in contrast to more archaic or regionally restricted Tupi varieties.[12][13] This perception aligns with its historical role as a simplified yet functional lingua franca, nativized among diverse Amazonian groups by the 18th century.[1] Colonial European observers, however, often characterized such hybridized Tupi forms—including the missionary-adapted varieties ancestral to Nheengatu—as "corrupt Tupi" (Tupi corrupto), critiquing their departure from the phonology and grammar of classical Tupinambá Tupi through European prosodic influences and lexical simplifications for evangelization.[14] This pejorative framing reflected observers' bias toward purist indigenous norms over pragmatic adaptations, despite the latter's empirical utility in colonial intercultural contexts.[15]Linguistic Classification

Genetic Affiliation within Tupi-Guarani

Nheengatu belongs to the Tupi-Guarani branch of the Tupi language family, descending directly from the Tupinambá dialect spoken along the Brazilian coast in the 16th century, a variety of the extinct Old Tupi.[16] Phylogenetic analyses using lexical data position it within Group I, Subgroup Ic, clustering closely with Tupinambá, Kokama, and Omagua based on shared cognate patterns derived from comparative wordlists.[16] Comparative linguistics demonstrates its genetic ties through high retention of core vocabulary matching Proto-Tupi-Guarani reconstructions, particularly in domains like body parts, numerals, and basic kinship terms, which exhibit low rates of replacement typical of inherited features.[16] For example, Nheengatu preserves approximately 73% lexical cognates with Tupinambá, reflecting direct descent rather than distant relatedness.[16] Within the broader Tupi-Guarani family, Nheengatu shows lexical similarity metrics of 71-76% shared cognates with other members, distinguishing it from more divergent Amazonian Tupi languages outside this range while aligning it more closely with northern subgroups than with southern varieties like Guarani.[16][17] Grammatical retention, such as serial verb constructions and alienable/inalienable possession marking, further supports this affiliation over substrate influences from non-Tupi sources.[16]Debates on Creole Status and Hybridization

Scholars debate whether Nheengatu qualifies as a creole language, given its exposure to Portuguese during colonial missionization and trade expansion in the Amazon basin from the 17th century onward. Proponents of creole status, such as those analyzing it as a Tupinambá-lexified creole, point to processes resembling pidginization and creolization in Jesuit missions, where diverse indigenous groups acquired a simplified variety of Tupinambá Tupi as a lingua franca, resulting in morphological and syntactic reduction due to widespread L2 learning by non-native speakers.[18] [19] This view emphasizes empirical markers like the incorporation of Portuguese loanwords, estimated to comprise a notable portion of the modern lexicon in domains such as technology and administration, alongside structural simplifications that deviate from ancestral Tupi complexity.[19] Counterarguments, drawing on models like Mufwene's language ecology, reject full creole classification, asserting that Nheengatu represents a restructured Tupi-Guarani koine emergent from dialect leveling among related indigenous languages, with Portuguese acting primarily as an adstrate rather than a dominant superstrate.[20] These linguists highlight the retention of core Tupi grammatical and syntactic features, such as agglutinative patterns, despite contact-induced changes, arguing that the absence of radical restructuring—typical of creoles with broken transmission—distinguishes it from classic examples; instead, evolution occurred through competition in a feature pool dominated by Tupi substrates, without the demographic disruptions defining creolization.[20] Empirical evidence includes continuity in native-speaker transmission post-mission era, as documented in historical linguistics surveys, underscoring substrate retention over wholesale simplification.[19] The hybridization evident in Nheengatu stems causally from colonial imperatives for efficient interethnic communication, facilitated by Jesuit administrative practices and riverine trade networks from the mid-1600s, which prioritized a shared medium among Arawak, Tukanoan, and Tupi groups over organic community-internal development.[20] This contact ecology, involving unbalanced power dynamics and evangelization goals, drove selective feature adoption from Portuguese into a Tupi matrix, yielding a pragmatic hybrid suited to frontier utility rather than endogenous evolution.[20] Such dynamics explain the language's persistence as an indigenous-led adaptation, distinct from Portuguese-based creoles elsewhere in the Americas.[19]Historical Development

Origins from Tupinambá Tupi

Nheengatu traces its roots to the Tupinambá variety of Tupi, a language spoken by indigenous groups along the northern Brazilian coast, particularly in regions like Maranhão and Pará, during the 16th century.[2] This coastal Tupi, also referred to as Brasílica, served as the primary linguistic base due to its widespread use among Tupian peoples encountered by early Portuguese colonizers and missionaries. Jesuit efforts to document and standardize the language began in the mid-16th century, with José de Anchieta composing a grammar between 1555 and 1556, later published in 1595, which captured Tupinambá's morphology and syntax while adapting it for broader utility.[6][1] The adaptation process involved simplifying Tupinambá's phonological and grammatical complexities—such as reducing agglutinative verb forms and nominal classifications—to accommodate non-native learners, including Portuguese clergy, settlers, and inland indigenous groups. This pragmatic modification, driven by missionary needs for evangelism among diverse tribes, transformed the language into a more pidgin-like form suitable for inter-ethnic communication, distinct from the fuller complexity of original Tupinambá. Early documentation reflects this shift, with Anchieta's work emphasizing practical descriptors over exhaustive native variation to prioritize teachability and doctrinal transmission.[6] Empirical evidence of proto-Nheengatu features appears in 17th-century religious texts, such as the catechism authored by Jesuit missionary João Filipe Bettendorf in 1687, which exhibits reduced inflectional paradigms and lexical borrowings indicative of early hybridization. These manuscripts, produced in Amazonian mission contexts, demonstrate the language's evolution from coastal Tupinambá toward a generalized variety, with simplified syntax facilitating rote learning of Christian tenets among multilingual audiences. Such texts provide the earliest verifiable attestations of these transitional traits, predating fuller inland divergence.Role as Colonial Lingua Franca

Nheengatu functioned as a pragmatic lingua franca during the 17th and 18th centuries in the Portuguese Amazonian colonies of Maranhão and Grão-Pará, enabling communication in Jesuit missions and trade expeditions along the Amazon and Rio Negro rivers.[21] By the late 1600s, it had been codified for evangelization, with Franciscans producing grammars based on Tupinambá variants and Jesuits employing it to catechize indigenous populations resettled in mission villages.[22] This adoption occurred across diverse ethnic groups, including Arawak-speaking peoples like the Baniwa, who integrated it through forced relocations, intermarriage, and bilingual interactions with colonizers, prioritizing utility over linguistic purity.[23][21] The language's spread facilitated Portuguese control by bridging communication gaps among heterogeneous indigenous captives, traders, and officials, who learned simplified forms for administrative and economic purposes.[21] Portuguese authorities formalized its role via the 1689 Carta Régia, designating it for instruction in indigenous aldeias, though by 1750 it was spoken throughout the colony except by some higher administrators resistant to vernacular use.[21] Contemporary accounts, such as that of João Daniel in 1757, described emergent variants as "corrupt" due to interference from speakers' native tongues, underscoring its evolution as a tool of expediency in colonial expansion rather than standardized doctrine.[21] By the early 1800s, Nheengatu had attained peak regional dominance, extending across the tri-border area of present-day Brazil, Peru, and Colombia, where it served diverse indigenous groups in interethnic exchanges and missionary outreach along riverine trade routes.[21][23] Its instrumental adoption by non-native speakers, including colonists and enslaved individuals, reinforced colonial hierarchies while enabling practical coordination in resource extraction and evangelization efforts.[22]Decline and Suppression in the 19th-20th Centuries

Following Brazil's independence from Portugal in 1822, the new nation's emphasis on Portuguese as the unifying official language accelerated the retreat of Nheengatu from its role as a regional lingua franca in the Amazon basin. Government policies prioritized Portuguese in administration, trade, and education to consolidate national identity, marginalizing indigenous and creolized languages like Nheengatu, which had previously facilitated communication among diverse ethnic groups including caboclos, indigenous peoples, and settlers.[6] This shift was enforced through restrictions on non-Portuguese languages in formal schooling, where instruction in vernaculars was prohibited to promote linguistic homogenization and loyalty to the central state.[24] The Cabanagem revolt of 1835–1840 in Pará, involving Nheengatu-speaking indigenous groups, caboclos, and others against provincial elites, intensified suppression efforts; the uprising's defeat led to reprisals that targeted linguistic mediums associated with resistance, further eroding Nheengatu's communal use.[6] By mid-century, expanding steamship navigation and early urbanization drew Portuguese-dominant migrants from coastal Brazil into Amazonia, diluting Nheengatu's speaker base through intermarriage and economic dependence on Portuguese-mediated networks.[6] In the 20th century, the Amazon rubber boom (circa 1879–1912) exacerbated language shift by attracting tens of thousands of migrant laborers from northeastern Brazil, who introduced Portuguese dialects and integrated indigenous workers into extractive economies requiring Portuguese for oversight and commerce.[25] Urban growth in riverine centers like Manaus and Belém, coupled with state-sponsored settlement, confined fluent Nheengatu transmission to remote indigenous pockets, as younger generations prioritized Portuguese for mobility and survival in expanding markets. By the late 1900s, speaker estimates had plummeted to approximately 19,600, reflecting a contraction from widespread colonial utility to endangered status amid these pressures.[1]Post-2000 Revival and Policy Recognition

In 2002, the municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira in Amazonas state enacted Municipal Law 145, granting co-official status to Nheengatu alongside Tukano and Baniwa, marking one of the earliest such recognitions for an indigenous language in Brazil.[26] This policy aimed to promote multilingual administration and education in a region where these languages are spoken by a majority of the indigenous population, though implementation has been limited by resource constraints and dominant Portuguese usage in formal domains.[27] Revival initiatives gained further momentum with the launch of the Nheengatu App in October 2021, the first mobile application dedicated to teaching an indigenous language in Brazil, focusing on the Tapajoara variant spoken in the Lower Amazon.[28] Supported by the Aldir Blanc Law and the Pará State Department of Culture, the app provides interactive lessons to facilitate learning among younger users, though its reach remains confined to urban and semi-urban indigenous communities with smartphone access.[28] A landmark policy event occurred in July 2023, when the Brazilian Federal Constitution was translated into Nheengatu for the first time, involving 15 bilingual indigenous translators from the Upper Rio Negro and Middle Tapajós regions.[29] Unveiled in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, this translation symbolizes heightened governmental acknowledgment of indigenous linguistic rights under the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, yet it has primarily served ceremonial and educational purposes rather than altering daily administrative practices.[29] Despite these recognitions, measurable outcomes indicate persistent challenges, including low rates of intergenerational transmission, as younger generations in Nheengatu-speaking communities increasingly prioritize Portuguese proficiency for economic opportunities and social mobility in broader Brazilian society. Policy efforts have not substantially reversed the language's shift toward diglossia, where Portuguese dominates intergenerational interactions outside traditional settings.Geographic Distribution and Demographics

Primary Regions of Use

Nheengatu is primarily spoken in the Brazilian Amazon region, with its core heartland in the Rio Negro basin of Amazonas state, encompassing the Upper and Middle Rio Negro areas. The municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira serves as a key concentration point, where the language holds co-official status alongside Portuguese, Baniwa, and Tukano. Approximately 8,000 speakers are reported in the Upper Rio Negro region alone.[27][22] The language extends transnationally into border areas of Venezuela, where it is known as Yeral, and Colombia, particularly among indigenous communities along the Rio Negro. In Venezuela, it is used by groups such as the Baré and Baniwa, though documentation remains limited. Colombian usage is similarly peripheral, tied to cross-border ethnic networks.[30][22] Within Brazil, peripheral variants persist among riverine communities in the lower Amazon and lower Madeira regions of Amazonas state, retaining more traditional phonological features. A distinct form is also attested in the Tapajós River area of Pará state, in northeastern Brazil, influenced by local indigenous groups like the Tapajoawara. Overall speaker numbers are estimated at around 19,000, with the vast majority concentrated in Amazonas state.[22]

Speaker Numbers and Transmission Rates

Nheengatu is classified as severely endangered by UNESCO, indicating that fluent speakers are primarily limited to older generations, with younger speakers, particularly children, predominantly shifting to Portuguese for daily communication.[3][31] This status reflects low intergenerational transmission, where parents often do not pass the language to children, resulting in L1 acquisition rates insufficient to sustain vitality without intervention.[3] Recent estimates place the number of Nheengatu speakers at approximately 20,000 across Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela as of the early 2020s, though figures vary due to inconsistent surveying in remote Amazonian regions.[3] Earlier assessments, such as those from 2010-2021, reported lower counts ranging from 6,000 to 8,000 in core areas like the Brazilian Amazon, highlighting a potential stabilization or slight increase amid documentation efforts but underscoring ongoing decline trajectories.[2][32] Transmission rates remain critically low, with fewer than half of children in speaker communities acquiring fluency as a first language, exacerbated by urban migration that disrupts traditional family-based learning and exposes youth to dominant Portuguese environments.[3] Pre-1988 monolingual education policies in Brazil further accelerated this shift by excluding indigenous languages from formal schooling, prioritizing assimilation and limiting opportunities for child speakers to develop proficiency.[33] Empirical surveys indicate that while some semi-speakers exist among middle-aged adults, full fluency is concentrated among those over 50, projecting a halving of proficient speakers within a generation absent reversal.[31]Sociolinguistic Dynamics

Domains of Usage and Functional Range

Nheengatu primarily functions in informal domains such as family conversations, inter-ethnic interactions among indigenous groups in the Upper Rio Negro basin, and the transmission of oral traditions including myths and narratives.[4][34] In communities like those of the Baniwa, Baré, and Warekena, it serves as a lingua franca for communication across ethnic lines, particularly in rural settings where speakers from diverse linguistic backgrounds interact daily.[4] Usage extends to rituals, such as the Baré Kariamã ceremony, and cultural expressions like songs, though these remain confined to indigenous contexts without broader dissemination.[34] In households, Nheengatu is often the default for older generations and monolingual children prior to schooling, but intergenerational shifts favor Portuguese, with parents code-switching or defaulting to it in the presence of younger family members to facilitate adaptation.[34][4] Empirical observations from multilingual families indicate prevalent code-mixing between Nheengatu and Portuguese, diluting monolingual proficiency and limiting the language's purity in extended discourse.[34] This pattern underscores Nheengatu's role more as an ethnic identity marker than a utility-driven medium, especially among youth exposed to urban influences. Formal domains exhibit stark constraints, with Portuguese dominating education, administration, and commerce, rendering Nheengatu largely absent from these spheres.[4][34] While limited media presence exists through bilingual indigenous publications and occasional social media content, commercial transactions and official proceedings rely exclusively on Portuguese, restricting Nheengatu to non-instrumental, expressive functions.[4] Surveys of speaker practices in São Gabriel da Cachoeira reveal that even in indigenous-majority areas, code-switching prevails in mixed-language environments, further marginalizing pure Nheengatu usage beyond private or ritualistic settings.[4]Endangerment Factors and Empirical Assessments

Nheengatu's endangerment is evidenced by disrupted intergenerational transmission, as children in speaker communities no longer routinely acquire the language from parents, placing it at Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIDS) level 7 (shifting) in Colombia and level 6b (vigorous but institutionalized) in Brazil.[35] Recent estimates indicate approximately 6,000 speakers in Brazil and 8,000 in Colombia, a modest base insufficient to withstand demographic pressures without sustained transmission.[35] These metrics underscore vulnerability, with the youngest fluent speakers increasingly belonging to older generations, signaling progression toward critical endangerment thresholds.[36] Primary causal drivers stem from socioeconomic incentives prioritizing Portuguese proficiency, the language of formal education, wage labor, and administrative functions in Brazil's Amazon basin, where indigenous speakers face barriers to economic participation without it.[37] Urbanization exacerbates this, as migration to cities exposes families to Portuguese-saturated environments, accelerating language attrition among youth through reduced domestic use and immersion in dominant media.[38] Exogamy, prevalent in the multilingual Upper Rio Negro region, further disrupts transmission by integrating non-Nheengatu spouses who default to Portuguese in households, diluting heritage language acquisition rates.[39] In competitive multilingual ecologies, such shifts favor languages offering tangible survival benefits, with Nheengatu's limited functional domains yielding to Portuguese's broader utility amid small community sizes and external influences.[40] This reflects empirical patterns observed across Brazilian indigenous languages, where speaker attrition correlates with integration into national economic structures rather than isolated vitality measures.[37]Language Policy Impacts in Brazil

The 1988 Constitution of Brazil marked a pivotal shift by recognizing indigenous peoples' rights to their languages and cultures, stipulating in Article 231 that the state must ensure respect for their social organization, customs, languages, beliefs, and traditions.[41] This provision elevated indigenous languages from suppressed colonial relics to constitutionally protected entities, though Portuguese remained the sole official national language. For Nheengatu, this framework laid groundwork for subsequent regional recognitions without mandating widespread practical enforcement.[24] In Amazonas state, Nheengatu achieved co-official status alongside Portuguese, Baniwa, and Tukano through Municipal Law No. 145 of November 28, 2002, in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, a municipality where it is widely spoken by indigenous and mixed populations. This policy aimed to facilitate local governance and services in multiple languages, reflecting the area's linguistic diversity. However, implementation has proven inconsistent, with reports indicating that the co-official designation has not translated into routine administrative use or robust institutional support, limiting its tangible effects on daily vitality.[26][6] A notable symbolic advancement occurred in July 2023, when the Federal Supreme Court unveiled the first translation of the 1988 Constitution into Nheengatu, produced by 15 indigenous translators and presented in São Gabriel da Cachoeira. This initiative, coordinated by the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, sought to enhance accessibility and cultural affirmation for speakers. Despite such gestures, empirical assessments reveal spotty integration into education and public services; bilingual programs exist but suffer from inadequate funding and teacher training, correlating with persistent intergenerational transmission gaps rather than a reversal of overall decline in speaker proficiency.[29][42]Controversies in Preservation vs. Assimilation

Advocates for Nheengatu preservation argue that maintaining the language safeguards indigenous cultural rights and facilitates identity reclamation, particularly in regions like the Upper Rio Negro where it serves as a marker of ethnic cohesion amid historical suppression.[27] This perspective aligns with Brazil's 1988 Constitution, which mandates intercultural bilingual education to support indigenous languages alongside Portuguese, viewing such policies as essential for countering assimilationist legacies from colonial and mid-20th-century missions that banned native tongues.[43] Pro-preservation efforts, often framed in multicultural terms, emphasize community-driven revitalization to preserve oral traditions and resist cultural erosion, as seen in co-official status grants in municipalities like São Gabriel da Cachoeira since 2002.[26] Critics of aggressive preservation, drawing on pragmatic adaptation arguments, contend that prioritizing Nheengatu over full Portuguese proficiency can hinder economic integration, as the national language remains indispensable for accessing legal rights, employment, and broader education systems beyond isolated communities.[44] In practice, indigenous speakers limited to minority languages face restricted mobility, with studies on Amazonian groups indicating that weak Portuguese skills correlate with lower socioeconomic outcomes in urban or market-oriented contexts.[45] This view highlights parallels to broader multilingual policy experiments where forced maintenance without economic viability leads to resource diversion without proportional gains, as bilingual programs often yield low returns on investment in speaker transmission rates.[46] Empirical data underscores these tensions: while Nheengatu revival initiatives have raised awareness, speaker numbers remain modest at approximately 8,000 in the Upper Rio Negro region, with intergenerational transmission challenged by youth migration and Portuguese dominance in formal domains.[27] Bilingual education assessments reveal mixed effectiveness, with many implementations failing to sustain language use or enhance academic performance, partly due to inadequate teacher training and community isolation.[46][47] Proponents counter that short-term costs are offset by long-term cultural resilience, yet sources critiquing such policies note a bias in academic literature toward preservation narratives, potentially overlooking causal links between linguistic assimilation and improved access to jobs and services in Brazil's Portuguese-centric economy.[48]Linguistic Features

Phonology

Nheengatu possesses a relatively simple consonant inventory of 13 to 15 phonemes, featuring voiceless stops at bilabial /p/, alveolar /t/, and velar /k/ positions; nasals /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/; prenasalized voiced stops /ᵐb/, ⁿd/, and ᵑɡ/; alveolar fricative /s/; approximants /w/, /j/, and flap /ɾ/; and a glottal stop /ʔ/ in certain dialects.[49][21] Voiced stops /b/, /d/, /g/ and additional fricatives like /ʃ/ and /h/ occur marginally or primarily in Portuguese loanwords, reflecting contact-induced expansion beyond the core Tupi-derived system.[49] This inventory represents a simplification from Old Tupi, which featured greater coda complexity and lacked widespread prenasalization, with modern Nheengatu reducing clusters and favoring open syllables.[21]| Place/ Manner | Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops (voiceless) | p | t | k | |||

| Stops (prenasalized) | ᵐb | ⁿd | ᵑɡ | |||

| Fricatives | s | ʃ (loans) | h (marginal) | |||

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ (dialectal) | ŋ | ||

| Approximants/Flaps | w | ɾ | j | ʔ |