Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chirality (chemistry)

View on Wikipedia

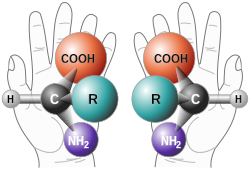

In chemistry, a molecule or ion is called chiral (/ˈkaɪrəl/) if it cannot be superposed on its mirror image by any combination of rotations, translations, and some conformational changes. This geometric property is called chirality (/kaɪˈrælɪti/).[1][2][3][4] The terms are derived from Ancient Greek χείρ (cheir) 'hand'; which is the canonical example of an object with this property.

A chiral molecule or ion exists in two stereoisomers that are mirror images of each other,[5] called enantiomers; they are often distinguished as either "right-handed" or "left-handed" by their absolute configuration or some other criterion. The two enantiomers have the same chemical properties, except when reacting with other chiral compounds. They also have the same physical properties, except that they often have opposite optical activities. A homogeneous mixture of the two enantiomers in equal parts, a racemic mixture, differs chemically and physically from the pure enantiomers.

Chiral molecules will usually have a stereogenic element from which chirality arises. The most common type of stereogenic element is a stereogenic center, or stereocenter. In the case of organic compounds, stereocenters most frequently take the form of a carbon atom with four distinct groups attached to it in a tetrahedral geometry. Less commonly, other atoms like N, P, S, and Si can also serve as stereocenters, provided they have four distinct substituents (including lone pair electrons) attached to them.

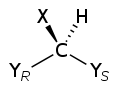

A given stereocenter has two possible configurations (R and S), which give rise to stereoisomers (diastereomers and enantiomers) in molecules with one or more stereocenter. For a chiral molecule with one or more stereocenter, the enantiomer corresponds to the stereoisomer in which every stereocenter has the opposite configuration. An organic compound with only one stereogenic carbon is always chiral. On the other hand, an organic compound with multiple stereogenic carbons is typically, but not always, chiral. In particular, if the stereocenters are configured in such a way that the molecule can take a conformation having a plane of symmetry or an inversion point, then the molecule is achiral and is known as a meso compound.

Molecules with chirality arising from one or more stereocenters are classified as possessing central chirality. There are two other types of stereogenic elements that can give rise to chirality, a stereogenic axis (axial chirality) and a stereogenic plane (planar chirality). Finally, the inherent curvature of a molecule can also give rise to chirality (inherent chirality). These types of chirality are far less common than central chirality. BINOL is a typical example of an axially chiral molecule, while trans-cyclooctene is a commonly cited example of a planar chiral molecule. Finally, helicene possesses helical chirality, which is one type of inherent chirality.

Chirality is an important concept for stereochemistry and biochemistry. Most substances relevant to biology are chiral, such as carbohydrates (sugars, starch, and cellulose), all but one of the amino acids that are the building blocks of proteins, and the nucleic acids. Naturally occurring triglycerides are often chiral, but not always. In living organisms, one typically finds only one of the two enantiomers of a chiral compound. For that reason, organisms that consume a chiral compound usually can metabolize only one of its enantiomers. For the same reason, the potencies or effects of enantiomers of a pharmaceutical can differ sharply.

Definition

[edit]The chirality of a molecule is based on the molecular symmetry of its conformations. A conformation of a molecule is chiral if and only if it belongs to the Cn, Dn, T, O, or I point groups (the chiral point groups). However, whether the molecule itself is considered to be chiral depends on whether its chiral conformations are persistent isomers that could be isolated as separated enantiomers, at least in principle, or the enantiomeric conformers rapidly interconvert at a given temperature and timescale through low-energy conformational changes (rendering the molecule achiral). For example, despite having chiral gauche conformers that belong to the C2 point group, butane is considered achiral at room temperature because rotation about the central C–C bond rapidly interconverts the enantiomers (3.4 kcal/mol barrier). Similarly, cis-1,2-dichlorocyclohexane consists of chair conformers that are nonidentical mirror images, but the two can interconvert via the cyclohexane chair flip (~10 kcal/mol barrier). As another example, amines with three distinct substituents (R1R2R3N:) are also regarded as achiral molecules because their enantiomeric pyramidal conformers rapidly undergo pyramidal inversion.

However, if the temperature in question is low enough, the process that interconverts the enantiomeric chiral conformations becomes slow compared to a given timescale. The molecule would then be considered to be chiral at that temperature. The relevant timescale is, to some degree, arbitrarily defined: 1000 seconds is sometimes employed, as this is regarded as the lower limit for the amount of time required for chemical or chromatographic separation of enantiomers in a practical sense. Molecules that are chiral at room temperature due to restricted rotation about a single bond (barrier to rotation ≥ ca. 23 kcal/mol) are said to exhibit atropisomerism.

A chiral compound can contain no improper axis of rotation (Sn), which includes planes of symmetry and inversion center. Chiral molecules are always dissymmetric (lacking Sn) but not always asymmetric (lacking all symmetry elements except the trivial identity). Asymmetric molecules are always chiral.[6]

The following table shows some examples of chiral and achiral molecules, with the Schoenflies notation of the point group of the molecule. In the achiral molecules, X and Y (with no subscript) represent achiral groups, whereas XR and XS or YR and YS represent enantiomers. Note that there is no meaning to the orientation of an S2 axis, which is just an inversion. Any orientation will do, so long as it passes through the center of inversion. Also note that higher symmetries of chiral and achiral molecules also exist, and symmetries that do not include those in the table, such as the chiral C3 or the achiral S4.

An example of a molecule that does not have a mirror plane or an inversion and yet would be considered achiral is 1,1-difluoro-2,2-dichlorocyclohexane (or 1,1-difluoro-3,3-dichlorocyclohexane). This may exist in many conformers (conformational isomers), but none of them has a mirror plane. In order to have a mirror plane, the cyclohexane ring would have to be flat, widening the bond angles and giving the conformation a very high energy. This compound would not be considered chiral because the chiral conformers interconvert easily.

An achiral molecule having chiral conformations could theoretically form a mixture of right-handed and left-handed crystals, as often happens with racemic mixtures of chiral molecules (see Chiral resolution#Spontaneous resolution and related specialized techniques), or as when achiral liquid silicon dioxide is cooled to the point of becoming chiral quartz.

Stereogenic centers

[edit]

A stereogenic center (or stereocenter) is an atom such that swapping the positions of two ligands (connected groups) on that atom results in a molecule that is stereoisomeric to the original. For example, a common case is a tetrahedral carbon bonded to four distinct groups a, b, c, and d (Cabcd), where swapping any two groups (e.g., Cbacd) leads to a stereoisomer of the original, so the central C is a stereocenter. Many chiral molecules have point chirality, namely a single chiral stereogenic center that coincides with an atom. This stereogenic center usually has four or more bonds to different groups and may be carbon (as in many biological molecules), phosphorus (as in many organophosphates), silicon, or a metal (as in many chiral coordination compounds). However, a stereogenic center can also be a trivalent atom whose bonds are not in the same plane, such as phosphorus in P-chiral phosphines (PRR′R″) and sulfur in S-chiral sulfoxides (OSRR′), because a lone-pair of electrons is present instead of a fourth bond.

Similarly, a stereogenic axis (or plane) is defined as an axis (or plane) in the molecule such that the swapping of any two ligands attached to the axis (or plane) gives rise to a stereoisomer. For instance, the C2-symmetric species 1,1′-bi-2-naphthol (BINOL) and 1,3-dichloroallene have stereogenic axes and exhibit axial chirality, while (E)-cyclooctene and many ferrocene derivatives bearing two or more substituents have stereogenic planes and exhibit planar chirality.

Chirality can also arise from isotopic differences between substituents, such as in the deuterated benzyl alcohol PhCHDOH; which is chiral and optically active ([α]D = 0.715°), even though the non-deuterated compound PhCH2OH is not.[7]

If two enantiomers easily interconvert, the pure enantiomers may be practically impossible to separate, and only the racemic mixture is observable. This is the case, for example, of most amines with three different substituents (NRR′R″), because of the low energy barrier for nitrogen inversion.

When the optical rotation for an enantiomer is too low for practical measurement, the species is said to exhibit cryptochirality.

Chirality is an intrinsic part of the identity of a molecule, so the systematic name includes details of the absolute configuration (R/S, D/L, or other designations).

Manifestations of chirality

[edit]- Flavor: the artificial sweetener aspartame has two enantiomers. L-aspartame tastes sweet whereas D-aspartame is tasteless.[8]

- Odor: R-(–)-carvone smells like spearmint whereas S-(+)-carvone smells like caraway.[9]

- Drug effectiveness: the antidepressant drug citalopram is sold as a racemic mixture. However, studies have shown that only the (S)-(+) enantiomer (escitalopram) is responsible for the drug's beneficial effects.[10][11]

- Drug safety: D‑penicillamine is used in chelation therapy and for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis whereas L‑penicillamine is toxic as it inhibits the action of pyridoxine, an essential B vitamin.[12]

In biochemistry

[edit]Many biologically active molecules are chiral, including the naturally occurring amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) and sugars.

The origin of this homochirality in biology is the subject of much debate.[13] Most scientists believe that Earth life's "choice" of chirality was purely random, and that if carbon-based life forms exist elsewhere in the universe, their chemistry could theoretically have opposite chirality. However, there is some suggestion that early amino acids could have formed in comet dust. In this case, circularly polarised radiation (which makes up 17% of stellar radiation) could have caused the selective destruction of one chirality of amino acids, leading to a selection bias which ultimately resulted in all life on Earth being homochiral.[14][15]

Enzymes, which are chiral, often distinguish between the two enantiomers of a chiral substrate. One could imagine an enzyme as having a glove-like cavity that binds a substrate. If this glove is right-handed, then one enantiomer will fit inside and be bound, whereas the other enantiomer will have a poor fit and is unlikely to bind.

L-forms of amino acids tend to be tasteless, whereas D-forms tend to taste sweet.[13] Spearmint leaves contain the L-enantiomer of the chemical carvone or R-(−)-carvone and caraway seeds contain the D-enantiomer or S-(+)-carvone.[9] The two smell different to most people because our olfactory receptors are chiral.

Chirality is important in context of ordered phases as well, for example the addition of a small amount of an optically active molecule to a nematic phase (a phase that has long range orientational order of molecules) transforms that phase to a chiral nematic phase (or cholesteric phase). Chirality in context of such phases in polymeric fluids has also been studied in this context.[16]

In inorganic chemistry

[edit]

Chirality is a symmetry property, not a property of any part of the periodic table. Thus many inorganic materials, molecules, and ions are chiral. Quartz is an example from the mineral kingdom. Such noncentric materials are of interest for applications in nonlinear optics.

In the areas of coordination chemistry and organometallic chemistry, chirality is pervasive and of practical importance. A famous example is tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) complex in which the three bipyridine ligands adopt a chiral propeller-like arrangement.[17] The two enantiomers of complexes such as [Ru(2,2′-bipyridine)3]2+ may be designated as Λ (capital lambda, the Greek version of "L") for a left-handed twist of the propeller described by the ligands, and Δ (capital delta, Greek "D") for a right-handed twist (pictured). dextro- and levo-rotation (the clockwise and counterclockwise optical rotation of plane-polarized light) uses similar notation, but shouldn't be confused.

Chiral ligands confer chirality to a metal complex, as illustrated by metal-amino acid complexes. If the metal exhibits catalytic properties, its combination with a chiral ligand is the basis of asymmetric catalysis.[18]

Methods and practices

[edit]The term optical activity is derived from the interaction of chiral materials with polarized light. In a solution, the (−)-form, or levorotatory form, of an optical isomer rotates the plane of a beam of linearly polarized light counterclockwise. The (+)-form, or dextrorotatory form, of an optical isomer does the opposite. The rotation of light is measured using a polarimeter and is expressed as the optical rotation.

Enantiomers can be separated by chiral resolution. This often involves forming crystals of a salt composed of one of the enantiomers and an acid or base from the so-called chiral pool of naturally occurring chiral compounds, such as malic acid or the amine brucine. Some racemic mixtures spontaneously crystallize into right-handed and left-handed crystals that can be separated by hand. Louis Pasteur used this method to separate left-handed and right-handed sodium ammonium tartrate crystals in 1849. Sometimes it is possible to seed a racemic solution with a right-handed and a left-handed crystal so that each will grow into a large crystal.

Liquid chromatography (HPLC and TLC) may also be used as an analytical method for the direct separation of enantiomers and the control of enantiomeric purity, e.g. active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) which are chiral.[19][20]

Miscellaneous nomenclature

[edit]- Any non-racemic chiral substance is called scalemic. Scalemic materials can be enantiopure or enantioenriched.[21]

- A chiral substance is enantiopure when only one of two possible enantiomers is present so that all molecules within a sample have the same chirality sense. Use of homochiral as a synonym is strongly discouraged.[22]

- A chiral substance is enantioenriched or heterochiral when its enantiomeric ratio is greater than 50:50 but less than 100:0.[23]

- Enantiomeric excess or e.e. is the difference between how much of one enantiomer is present compared to the other. For example, a sample with 40% e.e. of R contains 70% R and 30% S (70% − 30% = 40%).[24]

Computational prediction of chiral properties

[edit]The prediction of chiral properties using computational methods has emerged as an important area in modern stereochemistry[25][26], complementing experimental techniques for characterizing and separating enantiomers. These approaches leverage machine learning algorithms and molecular representations to predict various chiral-specific behaviors, including chromatographic retention, optical rotation, and stereochemical assignments[27].

Molecular representations for chirality

[edit]Computational methods for representing molecular chirality must encode three-dimensional stereochemical information in a format suitable for machine learning algorithms. SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) notation incorporates stereochemistry through the use of @ and @@ symbols at chiral centers, where @ typically denotes anticlockwise and @@ denotes clockwise configuration when viewing the chiral center along the bond from the center to the first atom in the SMILES string[28][29].

Traditional molecular descriptors used in computational chemistry, such as circular fingerprints (Extended Connectivity Fingerprints or ECFP[30]), can encode structural information including stereochemical features. These descriptors represent molecules as fixed-length binary vectors that capture local atomic environments and connectivity patterns. However, conventional fingerprints may not optimally capture the subtle three-dimensional differences between enantiomers.

Neural network-based molecular representations can be derived from SMILES strings. Variational autoencoders and heteroencoders trained on large databases of molecular structures can generate latent space vectors (LSVs) that encode molecular properties in a continuous, lower-dimensional space[31]. These methods calculate difference vectors between the descriptor of a molecule and that of its enantiomer, or between the original descriptor and one derived from a stereochemistry-depleted SMILES string. Such difference descriptors can amplify the stereochemical information relevant to chiral properties while reducing noise from other structural features[32].

Machine Learning applications

[edit]Machine learning models trained on these molecular representations have been applied to predict various chirality-related properties. One practical application is forecasting the elution order of enantiomers in chiral chromatography. Models trained on experimental retention data from chiral stationary phases can learn structure-retention relationships[27]. Random Forest and other ensemble methods have been applied to predict which enantiomer elutes first on columns such as Chiralpak AD-H using both traditional circular fingerprints and neural network-derived descriptors[32].

Another application is the prediction of optical rotation, a fundamental chiral property. Machine learning models have been developed to predict specific rotation values for chiral molecules based on their structure, with applications to both organic compounds and specialized classes such as chiral fluorinated molecules[25][26]. These predictions can assist in structural characterization and quality control in pharmaceutical development.

While these machine learning approaches show promise, several limitations remain. Model accuracy depends heavily on training data quality and coverage of chemical space. Neural network architectures, particularly Transformers, face inherent challenges in learning stereochemical features from string-based representations like SMILES[33]. These models tend to recognize partial molecular structures early in training but require significantly longer to accurately distinguish between enantiomers, sometimes exhibiting periods of confusion where @ and @@ tokens are frequently interchanged. The interpretability of neural network-based descriptors is often limited compared to traditional physically-motivated descriptors. Additionally, these methods typically perform best for compounds structurally similar to training data and may not generalize well to novel scaffolds or unusual stereochemical arrangements.

History

[edit]The rotation of plane polarized light by chiral substances was first observed by Jean-Baptiste Biot in 1812,[34] and gained considerable importance in the sugar industry, analytical chemistry, and pharmaceuticals. Louis Pasteur deduced in 1848 that this phenomenon has a molecular basis.[35][36] The term chirality itself was coined by Lord Kelvin in 1894.[37] Individual enantiomers or diastereomers of a compound were formerly called optical isomers due to their distinct optical properties.[38] At one time, chirality was thought to be restricted to organic chemistry, but this misconception was overthrown by the resolution of a purely inorganic compound, a cobalt complex called hexol, by Alfred Werner in 1911.[39]

In the early 1970s, various groups established that the human olfactory organ is capable of distinguishing chiral compounds.[9][40][41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Organic Chemistry (4th Edition) Paula Y. Bruice. Pearson Educational Books. ISBN 9780131407480

- ^ Organic Chemistry (3rd Edition) Marye Anne Fox, James K. Whitesell Jones & Bartlett Publishers (2004) ISBN 0763721972

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Chirality". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01058

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Superposability". doi:10.1351/goldbook.S06144

- ^ Howland, Robert H. (July 2009). "Understanding chirality and stereochemistry: three-dimensional psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 47 (7): 15–18. doi:10.3928/02793695-20090609-01. ISSN 0279-3695. PMID 19678474.

- ^ Cotton, F. A., "Chemical Applications of Group Theory," John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1990.

- ^ ^ Streitwieser, A. Jr.; Wolfe, J. R. Jr.; Schaeffer, W. D. (1959). "Stereochemistry of the Primary Carbon. X. Stereochemical Configurations of Some Optically Active Deuterium Compounds". Tetrahedron. 6 (4): 338–344. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(59)80014-4.

- ^ Gal, Joseph (2012). "The Discovery of Stereoselectivity at Biological Receptors: Arnaldo Piutti and the Taste of the Asparagine Enantiomers-History and Analysis on the 125th Anniversary". Chirality. 24 (12): 959–976. doi:10.1002/chir.22071. PMID 23034823.

- ^ a b c Theodore J. Leitereg; Dante G. Guadagni; Jean Harris; Thomas R. Mon; Roy Teranishi (1971). "Chemical and sensory data supporting the difference between the odors of the enantiomeric carvones". J. Agric. Food Chem. 19 (4): 785–787. Bibcode:1971JAFC...19..785L. doi:10.1021/jf60176a035.

- ^ Lepola U, Wade A, Andersen HF (May 2004). "Do equivalent doses of escitalopram and citalopram have similar efficacy? A pooled analysis of two positive placebo-controlled studies in major depressive disorder". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 19 (3): 149–55. doi:10.1097/00004850-200405000-00005. PMID 15107657. S2CID 36768144.

- ^ Hyttel, J.; Bøgesø, K. P.; Perregaard, J.; Sánchez, C. (1992). "The pharmacological effect of citalopram resides in the (S)-(+)-enantiomer". Journal of Neural Transmission. 88 (2): 157–160. doi:10.1007/BF01244820. PMID 1632943. S2CID 20110906.

- ^ JAFFE, IA; ALTMAN, K; MERRYMAN, P (Oct 1964). "The Antipyridoxine Effect of Penicillamine in Man". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 43 (10): 1869–73. doi:10.1172/JCI105060. PMC 289631. PMID 14236210.

- ^ a b Meierhenrich, Uwe J. (2008). Amino acids and the Asymmetry of Life. Berlin, GER: Springer. ISBN 978-3540768852.

- ^ McKee, Maggie (2005-08-24). "Space radiation may select amino acids for life". New Scientist. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ^ Meierhenrich Uwe J., Nahon Laurent, Alcaraz Christian, Hendrik Bredehöft Jan, Hoffmann Søren V., Barbier Bernard, Brack André (2005). "Asymmetric Vacuum UV photolysis of the Amino Acid Leucine in the Solid State". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44 (35): 5630–5634. Bibcode:2005ACIE...44.5630M. doi:10.1002/anie.200501311. PMID 16035020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Srinivasarao, M. (1999). "Chirality and Polymers". Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 4 (5): 369–376. doi:10.1016/S1359-0294(99)00024-2.

- ^ von Zelewsky, A. (1995). Stereochemistry of Coordination Compounds. Chichester: John Wiley.. ISBN 047195599X.

- ^ Hartwig, J. F. Organotransition Metal Chemistry, from Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books: New York, 2010. ISBN 189138953X

- ^ Bhushan, R.; Tanwar, S. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1395–1398. (doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2009.12.071)

- ^ Ravi Bhushan Chem. Rec. 2022, e102100295. (doi:10.1002/tcr.202100295)

- ^ Eliel, E.L. (1997). "Infelicitous Stereochemical Nomenclatures". Chirality. 9 (56): 428–430. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-636x(1997)9:5/6<428::aid-chir5>3.3.co;2-e. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "asymmetric synthesis". doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02072

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "enantiomerically enriched (enantioenriched)". doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02071

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "enantiomer excess (enantiomeric excess)". doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02070

- ^ a b Chen, Mengyao; Wu, Ting; Xiao, Kaixia; Zhao, Tanfeng; Zhou, Yanmei; Zhang, Qingyou; Aires-de-Sousa, Joao (2019-12-05). "Machine learning to predict the specific optical rotations of chiral fluorinated molecules". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 223: 117289. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2019.117289. ISSN 1386-1425.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: article number as page number (link) - ^ a b Mamede, Rafael; de-Almeida, Bruno Simões; Chen, Mengyao; Zhang, Qingyou; Aires-de-Sousa, Joao (2021-01-25). "Machine Learning Classification of One-Chiral-Center Organic Molecules According to Optical Rotation". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 61 (1): 67–75. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00876. ISSN 1549-9596.

- ^ a b Hong, Yuhui; Welch, Christopher J.; Piras, Patrick; Tang, Haixu (2024-02-13). "Enhanced Structure-Based Prediction of Chiral Stationary Phases for Chromatographic Enantioseparation from 3D Molecular Conformations". Analytical Chemistry. 96 (6): 2351–2359. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.3c04028. ISSN 0003-2700.

- ^ Weininger, David (1988-02-01). "SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules". Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences. 28 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1021/ci00057a005. ISSN 0095-2338.

- ^ "Daylight Theory: SMILES". www.daylight.com. Retrieved 2025-10-28.

- ^ Rogers, David; Hahn, Mathew (2010-05-24). "Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 50 (5): 742–754. doi:10.1021/ci100050t. ISSN 1549-9596.

- ^ Gómez-Bombarelli, Rafael; Wei, Jennifer N.; Duvenaud, David; Hernández-Lobato, José Miguel; Sánchez-Lengeling, Benjamín; Sheberla, Dennis; Aguilera-Iparraguirre, Jorge; Hirzel, Timothy D.; Adams, Ryan P.; Aspuru-Guzik, Alán (2018-02-28). "Automatic Chemical Design Using a Data-Driven Continuous Representation of Molecules". ACS Central Science. 4 (2): 268–276. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.7b00572. ISSN 2374-7943. PMC 5833007. PMID 29532027.

- ^ a b Baimacheva, N., Gao, X. & Aires-de-Sousa (2025). "Evaluation of chirality descriptors derived from SMILES heteroencoders". Journal of Cheminformatics. 17 (1): article number 137. doi:10.1186/s13321-025-01080-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yoshikai, Yasuhiro; Mizuno, Tadahaya; Nemoto, Shumpei; Kusuhara, Hiroyuki (2024-02-16). "Difficulty in chirality recognition for Transformer architectures learning chemical structures from string representations". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 1197. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-45102-8. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ Frankel, Eugene (1976). "Corpuscular Optics and the Wave Theory of Light: The Science and Politics of a Revolution in Physics". Social Studies of Science. 6 (2). Sage Publications Inc.: 147–154. doi:10.1177/030631277600600201. JSTOR 284930. S2CID 122887123.

- ^ Pasteur, L. (1848). Researches on the molecular asymmetry of natural organic products, English translation of French original, published by Alembic Club Reprints (Vol. 14, pp. 1–46) in 1905, facsimile reproduction by SPIE in a 1990 book.

- ^ Eliel, Ernest Ludwig; Wilen, Samuel H.; Mander, Lewis N. (1994). "Chirality in Molecules Devoid of Chiral Centers (Chapter 14)". Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds (1st ed.). New York, NY, USA: Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0471016700. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Bentley, Ronald (1995). "From Optical Activity in Quartz to Chiral Drugs: Molecular Handedness in Biology and Medicine". Perspect. Biol. Med. 38 (2): 188–229. doi:10.1353/pbm.1995.0069. PMID 7899056. S2CID 46514372.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Optical isomers". doi:10.1351/goldbook.O04308

- ^ Werner, A. (May 1911). "Zur Kenntnis des asymmetrischen Kobaltatoms. I". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 44 (2): 1887–1898. doi:10.1002/cber.19110440297.

- ^ Friedman, L.; Miller, J. G. (1971). "Odor Incongruity and Chirality". Science. 172 (3987): 1044–1046. Bibcode:1971Sci...172.1044F. doi:10.1126/science.172.3987.1044. PMID 5573954. S2CID 25725148.

- ^ Ohloff, Günther; Vial, Christian; Wolf, Hans Richard; Job, Kurt; Jégou, Elise; Polonsky, Judith; Lederer, Edgar (1980). "Stereochemistry-Odor Relationships in Enantiomeric Ambergris Fragrances". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 63 (7): 1932–1946. Bibcode:1980HChAc..63.1932O. doi:10.1002/hlca.19800630721.

Further reading

[edit]- Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart (2012). Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 319f, 432, 604np, 653, 746int, 803ketals, 839, 846f. ISBN 978-0199270293. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Eliel, Ernest Ludwig; Wilen, Samuel H.; Mander, Lewis N. (1994). "Chirality in Molecules Devoid of Chiral Centers (Chapter 14)". Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds. Vol. 9 (1st ed.). New York, NY, USA: Wiley & Sons. pp. 428–430. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1997)9:5/6<428::AID-CHIR5>3.0.CO;2-1. ISBN 978-0471016700. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Eliel, E.L. (1997). "Infelicitous Stereochemical Nomenclatures". Chirality. 9 (5–6): 428–430. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1997)9:5/6<428::AID-CHIR5>3.0.CO;2-1. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- Gal, Joseph (2013). "Molecular Chirality: Language, History, and Significance". Chirality. Topics in Current Chemistry. 340: 1–20. doi:10.1007/128_2013_435. ISBN 978-3-319-03238-2. PMID 23666078.

External links

[edit]- 21st International Symposium on Chirality

- STEREOISOMERISM - OPTICAL ISOMERISM

- Symposium highlights-Session 5: New technologies for small molecule synthesis

- IUPAC nomenclature for amino acid configurations.

- Michigan State University's explanation of R/S nomenclature

- Chirality & Odour Perception at leffingwell.com

- Chirality & Bioactivity I.: Pharmacology

- Chirality and the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

- The Handedness of the Universe by Roger A Hegstrom and Dilip K Kondepudi http://quantummechanics.ucsd.edu/ph87/ScientificAmerican/Sciam/Hegstrom_The_Handedness_of_the_universe.pdf