Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Carvone

View on Wikipedia | |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Methyl-5-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-2-en-1-one | |||

| Other names

2-Methyl-5-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-2-enone

2-Methyl-5-(1-methylethenyl)-2-cyclohexenone[1] Δ6:8(9)-p-Menthadien-2-one 1-Methyl-4-isopropenyl-Δ6-cyclohexen-2-one Carvol (obsolete) | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

| ||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.508 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C10H14O | |||

| Molar mass | 150.22 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Clear, colorless liquid | ||

| Density | 0.96 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 25.2 °C (77.4 °F; 298.3 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 231 °C (448 °F; 504 K) (91 °C @ 5 mmHg) | ||

| Insoluble (cold) Slightly soluble (hot)/soluble in trace amounts | |||

| Solubility in ethanol | Soluble | ||

| Solubility in diethyl ether | Soluble | ||

| Solubility in chloroform | Soluble | ||

Chiral rotation ([α]D)

|

−61° (R)-Carvone 61° (S)-Carvone | ||

| −92.2×10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Flammable | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H304, H315, H317, H411 | |||

| P261, P264, P270, P272, P273, P280, P301+P310, P301+P312, P302+P352, P321, P330, P331, P332+P313, P333+P313, P362, P363, P391, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related ketone

|

menthone dihydrocarvone carvomenthone | ||

Related compounds

|

limonene, menthol, p-cymene, carveol | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Carvone is a member of a family of chemicals called terpenoids.[2] Carvone is found naturally in many essential oils, but is most abundant in the oils from seeds of caraway (Carum carvi), spearmint (Mentha spicata), and dill.[3]

Uses

[edit]Food applications

[edit]Both carvones are used in the food and flavor industry. As the compound most responsible for the flavor of caraway, dill, and spearmint, carvone has been used for millennia in food.[3] Food applications are mainly met by carvone made from limonene. R-(−)-Carvone is also used for air freshening products and, like many essential oils, oils containing carvones are used in aromatherapy and alternative medicine.

Agriculture

[edit]S-(+)-Carvone is also used to prevent premature sprouting of potatoes during storage, being marketed in the Netherlands for this purpose under the name Talent.[3]

Insect control

[edit]R-(−)-Carvone has been approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for use as a mosquito repellent.[4]

Stereoisomerism and odor

[edit]

Carvone has two mirror image forms, or enantiomers: R-(−)-carvone, the sweetish minty smell of spearmint leaves. Its mirror image, S-(+)-carvone, has a spicy aroma with notes of rye, and gives caraway seeds their smell.[5][6]

The fact that the two enantiomers are perceived as smelling different is evidence that olfactory receptors must respond more strongly to one enantiomer than to the other. Not all enantiomers have distinguishable odors. Squirrel monkeys have also been found to be able to discriminate between carvone enantiomers.[7]

The two forms are also referred to, in older texts, by their optical rotations of laevo (l) referring to R-(−)-carvone, and dextro (d) referring to S-(+)-carvone. Modern naming refers to levorotatory isomers with the sign (−) and dextrorotatory isomers with the sign (+) in the systematic name.

Occurrence

[edit]S-(+)-Carvone is the principal constituent (60–70%) of the oil from caraway seeds (Carum carvi),[8] which is produced on a scale of about 10 tonnes per year.[3] It also occurs to the extent of about 40–60% in dill seed oil (from Anethum graveolens), and also in mandarin orange peel oil. R-(−)-Carvone is also the most abundant compound in the essential oil from several species of mint, particularly spearmint oil (Mentha spicata), which is composed of 50–80% R-(−)-carvone.[9] Spearmint is a major source of naturally produced R-(−)-carvone. However, the majority of R-(−)-carvone used in commercial applications is synthesized from R-(+)-limonene.[10] The R-(−)-carvone isomer also occurs in kuromoji oil. Some oils, like gingergrass oil, contain a mixture of both enantiomers. Many other natural oils, for example peppermint oil, contain trace quantities of carvones.

History

[edit]Caraway was used for medicinal purposes by the ancient Romans,[3] but carvone was probably not isolated as a pure compound until Franz Varrentrapp (1815–1877) obtained it in 1849.[2][11] It was originally called carvol by Schweizer. Goldschmidt and Zürrer identified it as a ketone related to limonene,[12] and the structure was finally elucidated by Georg Wagner (1849–1903) in 1894.[13]

Preparation

[edit]Carvone can be obtained from natural sources but insufficient is available to meet demand. Instead most carvone is produced from limonene.

The dextro-form, S-(+)-carvone is obtained practically pure by the fractional distillation of caraway oil. The levo-form obtained from the oils containing it usually requires additional treatment to produce high purity R-(−)-carvone. This can be achieved by the formation of an addition compound with hydrogen sulfide, from which carvone may be regenerated by treatment with potassium hydroxide followed by steam distillation.

Carvone may be synthetically prepared from limonene by first treating limonene with nitrosyl chloride. Heating this nitroso compound gives carvoxime. Treating carvoxime with oxalic acid yields carvone.[14] This procedure affords R-(−)-carvone from R-(+)-limonene.

The major use of d-limonene is as a precursor to S-(+)-carvone. The large scale availability of orange rinds, a byproduct in the production of orange juice, has made limonene cheaply available, and synthetic carvone correspondingly inexpensively prepared.[15]

The biosynthesis of carvone is by oxidation of limonene.

Chemical properties

[edit]Reduction

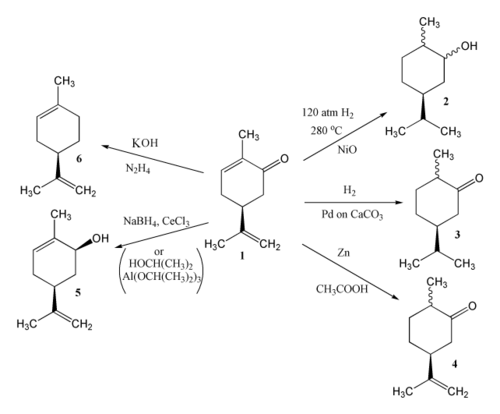

[edit]There are three double bonds in carvone capable of reduction; the product of reduction depends on the reagents and conditions used.[2] Catalytic hydrogenation of carvone (1) can give either carvomenthol (2) or carvomenthone (3). Zinc and acetic acid reduce carvone to give dihydrocarvone (4). MPV reduction using propan-2-ol and aluminium isopropoxide effects reduction of the carbonyl group only to provide carveol (5); a combination of sodium borohydride and CeCl3 (Luche reduction) is also effective. Hydrazine and potassium hydroxide give limonene (6) via a Wolff–Kishner reduction.

Oxidation

[edit]Oxidation of carvone can also lead to a variety of products.[2] In the presence of an alkali such as Ba(OH)2, carvone is oxidised by air or oxygen to give the diketone 7. With hydrogen peroxide the epoxide 8 is formed. Carvone may be cleaved using ozone followed by steam, giving dilactone 9, while KMnO4 gives 10.

Conjugate additions

[edit]As an α,β;-unsaturated ketone, carvone undergoes conjugate additions of nucleophiles. For example, carvone reacts with lithium dimethylcuprate to place a methyl group trans to the isopropenyl group with good stereoselectivity. The resulting enolate can then be allylated using allyl bromide to give ketone 11.[16]

Other

[edit]Being available inexpensively in enantiomerically pure forms, carvone is an attractive starting material for the asymmetric total synthesis of natural products. For example, (S)-(+)-carvone was used to begin a 1998 synthesis of the terpenoid quassin:[17]

In 1908, it was reported that exposure of carvone to "Italian sunlight" for one year gives carvone-camphor.[18] See enone–alkene cycloadditions.

Metabolism

[edit]In the body, in vivo studies indicate that both enantiomers of carvone are mainly metabolized into dihydrocarvonic acid, carvonic acid and uroterpenolone.[19] (–)-Carveol is also formed as a minor product via reduction by NADPH. (+)-Carvone is likewise converted to (+)-carveol.[20] This mainly occurs in the liver and involves cytochrome P450 oxidase and (+)-trans-carveol dehydrogenase.

References

[edit]- ^ Vollhardt, K. Peter C.; Schore, Neil E. (2007). Organic Chemistry (5th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. p. 173.

- ^ a b c d Simonsen, J. L. (1953). The Terpenes. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 394–408.

- ^ a b c d e De Carvalho, C. C. C. R.; Da Fonseca, M. M. R. (2006). "Carvone: Why and how should one bother to produce this terpene". Food Chemistry. 95 (3): 413–422. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.01.003.

- ^ "Document Display (PURL) | NSCEP | US EPA". nepis.epa.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ^ Theodore J. Leitereg; Dante G. Guadagni; Jean Harris; Thomas R. Mon; Roy Teranishi (1971). "Chemical and sensory data supporting the difference between the odors of the enantiomeric carvones". J. Agric. Food Chem. 19 (4): 785–787. doi:10.1021/jf60176a035.

- ^ Morcia, Caterina; Tumino, Giorgio; Ghizzoni, Roberta; Terzi, Valeria (2016). "Carvone (Mentha spicata L.) Oils - Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor and Safety - Chapter 35". Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor and Safety: 309–316. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-416641-7.00035-3.

- ^ Laska, M.; Liesen, A.; Teubner, P. (1999). "Enantioselectivity of odor perception in squirrel monkeys and humans". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 277 (4): R1098–R1103. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.4.r1098. PMID 10516250.

- ^ Hornok, L. Cultivation and Processing of Medicinal Plants, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK, 1992.

- ^ [1] Archived 2012-04-10 at the Wayback Machine, Chemical composition of essential oil from several species of mint (Mentha spp.)

- ^ Fahlbusch, Karl-Georg; Hammerschmidt, Franz-Josef; Panten, Johannes; Pickenhagen, Wilhelm; Schatkowski, Dietmar; Bauer, Kurt; Garbe, Dorothea; Surburg, Horst (2003). "Flavors and Fragrances". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_141. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Handwörterbuch der reinen und angewandten Chemie [Concise dictionary of pure and applied chemistry] (Braunschweig, (Germany): Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn, 1849), vol. 4, pages 686-688. [Notes: (1) Varrentrapp purified carvone by mixing oil of caraway with alcohol that had been saturated with hydrogen sulfide and ammonia; the reaction produced a crystalline precipitate, from which carvone could be recovered by adding potassium hydroxide in alcohol to the precipitate, and then adding water; (2) Varrentrapp's empirical formula for carvone is incorrect because chemists at that time used the wrong atomic masses for the elements; e.g., carbon (6 instead of 12).]

- ^ Heinrich Goldschmidt and Robert Zürrer (1885) "Ueber das Carvoxim," Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, 18 : 1729–1733.

- ^ Georg Wagner (1894) "Zur Oxydation cyklischer Verbindungen" (On the oxidation of cyclic compounds), Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin, vol. 27, pages 2270-2276. [Notes: (1) Georg Wagner (1849–1903) is the Germanized form of "Egor Egorovich Vagner", who was born in Russia and worked in Warsaw (See brief biography here.); (2) Wagner did not prove the structure of carvone in this paper; he merely proposed it as plausible; its correctness was proved later.]

- ^ Rothenberger, Otis S.; Krasnoff, Stuart B.; Rollins, Ronald B. (1980). "Conversion of (+)-Limonene to (−)-Carvone: An organic laboratory sequence of local interest". Journal of Chemical Education. 57 (10): 741. Bibcode:1980JChEd..57..741R. doi:10.1021/ed057p741.

- ^ Karl-Georg Fahlbusch, Franz-Josef Hammerschmidt, Johannes Panten, Wilhelm Pickenhagen, Dietmar Schatkowski, Kurt Bauer, Dorothea Garbe, Horst Surburg "Flavors and Fragrances" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2002, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_141

- ^ Srikrishna, A.; Jagadeeswar Reddy, T. (1998). "Enantiospecific synthesis of (+)-(1S, 2R, 6S)-1, 2-dimethylbicyclo [4.3. 0] nonan-8-one and (−)-7-epibakkenolide-A". Tetrahedron. 54 (38): 11517–11524. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(98)00672-3.

- ^ (a) Shing, T. K. M.; Jiang, Q; Mak, T. C. W. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2056-2057. (b) Shing, T. K. M.; Tang, Y. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1994, 1625

- ^ Ciamician, G.; Silber. P. (1908). "Chemische Lichtwirkungen". Ber. 41 (2): 1928. doi:10.1002/cber.19080410272.

- ^ Engel, W. (2001). "In vivo studies on the metabolism of the monoterpenes S-(+)- and R-(−)-carvone in humans using the metabolism of ingestion-correlated amounts (MICA) approach". J. Agric. Food Chem. 49 (8): 4069–4075. doi:10.1021/jf010157q. PMID 11513712.

- ^ Jager, W.; Mayer, M.; Platzer, P.; Reznicek, G.; Dietrich, H.; Buchbauer, G. (2000). "Stereoselective metabolism of the monoterpene carvone by rat and human liver microsomes". Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 52 (2): 191–197. doi:10.1211/0022357001773841. PMID 10714949. S2CID 41116690.

External links

[edit]- Carvone at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

Carvone

View on GrokipediaStructure and stereochemistry

Molecular structure

Carvone possesses the molecular formula CHO and is classified as a monoterpenoid ketone belonging to the p-menthane family. Its systematic IUPAC name is 2-methyl-5-(prop-1-en-2-yl)cyclohex-2-en-1-one, reflecting the core cyclohexene ring structure numbered such that the ketone carbonyl is at carbon 1, the endocyclic double bond spans carbons 2 and 3, a methyl substituent is attached to carbon 2, and the isopropenyl side chain (prop-1-en-2-yl, featuring a terminal double bond between carbons 1' and 2' with a methyl at 2') is bonded to carbon 5. In skeletal formula representations, the cyclohexene ring is depicted as a hexagon with the C2=C3 double bond, the C1 carbonyl, the C2 methyl branch, and the C5 isopropenyl as a vinyl group with a geminal methyl. The molecule's architecture centers on this substituted cyclohexenone, where the ketone at position 1 is directly conjugated to the adjacent C2=C3 double bond, forming an α,β-unsaturated ketone system that enhances electrophilicity at the β-carbon and enables characteristic conjugate addition reactions. Carvone is structurally derived from limonene as an oxidized precursor, sharing the isopropenyl side chain and cyclohexene backbone but featuring the introduced enone functionality in place of limonene's bis-alkene motif. In terms of three-dimensional conformation, the cyclohexene ring adopts a half-chair geometry, with carbons 1, 2, 3, and 4 roughly coplanar, carbons 5 and 6 displaced in opposite directions from the plane, minimizing strain while positioning the isopropenyl group preferentially in a pseudo-equatorial orientation.[5]Stereoisomers

Carvone features a single chiral center at carbon 5 in its cyclohexene ring, where the isopropenyl substituent is attached, leading to a pair of enantiomers: (5R)-(-)-carvone and (5S)-(+)-carvone.[6][7] The absolute configurations of these enantiomers are assigned using the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority rules, which rank the substituents attached to C5 based on atomic number and subsequent atoms. For the (5R)-enantiomer, with the lowest-priority hydrogen atom pointing away from the observer, the priority sequence—isopropenyl group (priority 1), the ring chain leading to the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl (priority 2), the other ring chain (priority 3)—traces a clockwise path. The (5S)-enantiomer exhibits the mirror-image counterclockwise arrangement. The enantiomeric structures are non-superimposable mirror images, identical in all physical properties except for their interaction with plane-polarized light and chiral environments.[6][7][8] These enantiomers display opposite optical rotations: [α]D = −61° (neat) for (5R)-(-)-carvone and [α]D = +61° (neat) for (5S)-(+)-carvone.[8][9] The stereochemistry influences sensory perception, with each enantiomer imparting distinct odors, though detailed olfactory differences are addressed elsewhere.[8]Odor and sensory properties

Carvone exists as two enantiomers with distinctly different olfactory profiles due to their chiral structures. The (R)-(-)-carvone enantiomer possesses a fresh, minty odor reminiscent of spearmint leaves, while the (S)-(+)-carvone enantiomer has a herbaceous, spicy scent similar to caraway or rye seeds.[10] These qualitative differences arise from interactions with chiral olfactory receptors in the nasal epithelium. Historically, the enantiomers were named based on their optical rotation: "laevo-carvone" for the levorotatory (R)-(-)-form and "dextro-carvone" for the dextrorotatory (S)-(+)-form, reflecting their specific rotation values of approximately -61° and +62°, respectively. This nomenclature predates modern stereochemical designations and was established through early isolations from natural sources like spearmint and caraway oils.[10] Human olfaction exhibits enantioselectivity for carvone, allowing differentiation between the enantiomers despite their structural similarity, primarily through activation of specific olfactory receptors that respond differently to each form.[11] Sensory studies confirm this, with humans achieving high discrimination accuracy (over 90%) in tasks distinguishing the enantiomers at concentrations around 100 ppb.[12] Similarly, squirrel monkeys demonstrate robust enantioselective perception, correctly identifying carvone enantiomers in conditioning paradigms with near-perfect performance, indicating conserved mechanisms across primates.[13] Olfactory detection thresholds for the carvone enantiomers in humans differ, with (R)-(-)-carvone detectable at 2–43 ppb and (S)-(+)-carvone at 85–600 ppb, underscoring their potency despite qualitative differences.[14] In sensory evaluations, intensity ratings on visual analog scales show the spearmint-like (R)-(-)-carvone often perceived as slightly milder at equimolar concentrations compared to the more pungent caraway-like (S)-(+)-carvone, though individual variability exists.[15] These thresholds establish carvone as a potent odorant, detectable at parts-per-billion levels that align with its natural concentrations in essential oils.[16]Physical and chemical properties

Physical properties

Carvone is typically obtained as a colorless to pale yellow liquid at room temperature. The enantiopure forms, (-)-carvone and (+)-carvone, exhibit similar appearances, with (-)-carvone described as colorless to pale strawberry-colored and (+)-carvone as pale yellow or colorless.[6][7] The racemic mixture also presents as a clear, colorless liquid. The density of carvone is approximately 0.96 g/cm³ at 20–25 °C across its forms, with values ranging from 0.956–0.960 g/cm³ for (-)-carvone and 0.956–0.965 g/cm³ for (+)-carvone.[6][7] Its boiling point is 227–231 °C at 760 mmHg, consistent for both enantiomers and the racemate. The melting point of the racemic form is 25.2 °C, while the enantiopure isomers have lower values below 15 °C.[6][7] Carvone shows low solubility in water, approximately 1.3 mg/mL (1.3 g/L or 0.13 g/100 mL) at 25 °C, for all forms. It is highly soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol (miscible), diethyl ether, and chloroform.[6][7] The refractive index (n_D^{20}) is around 1.497–1.502, with minimal variation between enantiomers.[6][7] Kinematic viscosity is approximately 24.7 mm²/s at 20 °C for (+)-carvone, and the flash point is 89 °C (192 °F).[7]| Property | Value (racemic/enantiopure) | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Density | 0.96 g/cm³ | 20–25 °C |

| Boiling point | 227–231 °C | 760 mmHg |

| Melting point | 25.2 °C (racemic); <15 °C (enantiopure) | - |

| Water solubility | 1.3 g/L (0.13 g/100 mL) | 25 °C |

| Refractive index | 1.497–1.502 (n_D^{20}) | 20 °C |

| Kinematic viscosity | ~24.7 mm²/s | 20 °C |

| Flash point | 89 °C | - |

Reduction reactions

Carvone undergoes selective hydrogenation reactions that target either the α,β-unsaturated ketone or the isolated double bond, yielding dihydrocarvone or carveol, respectively, with stereochemical control depending on the catalyst and conditions.[18] Using palladium on carbon (Pd/C) or supported Pd catalysts such as Pd/Al₂O₃ under mild conditions (e.g., ambient pressure, 423 K, H₂/carvone ratio of 1/6), carvone is hydrogenated primarily to carveol via selective C=O reduction, often as an intermediate en route to carvacrol, with selectivities up to 100% for the alcohol under H₂-lean conditions.[19][20] For C=C bond reduction, catalysts like Pd-black or Au/TiO₂ promote formation of dihydrocarvone (carvotanacetone), with Pd-black showing stepwise selectivity through carvotanacetone intermediates and Au/TiO₂ achieving 62% selectivity at 90% conversion (100 °C, 9 bar H₂ in methanol), with a trans/cis ratio ≈ 1:8 (favoring the cis-isomer).[18][21] The general equation for dihydrocarvone formation is: Stereochemical outcomes vary; for example, hydrogenation of (+)-carvone on Pd yields predominantly (R)-carvotanacetone with high diastereoselectivity in early stages.[18] The Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley (MPV) reduction of carvone employs aluminum isopropoxide in dry isopropyl alcohol as the hydride source, selectively reducing the carbonyl to carveol with moderate diastereoselectivity favoring the trans-isomer.[22] This method produces a mixture of trans- and cis-carveol. The reaction proceeds via a six-membered transition state, ensuring chemoselectivity over the C=C bond.[23] Enzymatic reductions of carvone to carveol utilize NADPH-dependent oxidoreductases, such as Old Yellow Enzymes (OYEs) from Saccharomyces pastorianus, achieving high stereoselectivity in non-metabolic contexts.[24] OYE1 catalyzes the hydride transfer from NADPH to the carbonyl, yielding (R)-carveol with >99% ee, enabling access to enantioenriched products for synthesis.[24] These biocatalysts offer complementary stereocomplementarity through enzyme variants, contrasting direct chemical reductions.[24]Oxidation reactions

Carvone undergoes a variety of oxidation reactions that target its endocyclic conjugated double bond and exocyclic isopropenyl double bond, leading to epoxides, diols, and cleavage products depending on the conditions and reagents employed. Epoxidation of carvone exhibits high regioselectivity based on the oxidizing agent. Treatment with m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA) selectively epoxidizes the electron-deficient endocyclic double bond to afford 3-methyl-6-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-7-oxabicyclo[4.1.0]heptan-2-one in good yield (typically 70-80%). In contrast, alkaline hydrogen peroxide epoxidizes the more electron-rich exocyclic double bond, yielding 5-(oxiran-2-yl)-2-methylcyclohex-2-en-1-one with comparable efficiency. This regioselectivity stems from the conjugative withdrawal of electrons by the adjacent carbonyl group, rendering the endocyclic alkene more reactive toward electrophilic peracids, whereas the basic medium enhances nucleophilic attack on the isolated exocyclic alkene by the hydroperoxide anion.[25] The epoxidation process is stereospecific, with the oxygen delivery occurring preferentially from the less hindered α-face in (R)-(-)-carvone, preserving the natural (5R) configuration at the chiral center. Computational studies confirm a concerted, asynchronous mechanism for peracid epoxidation, with low diastereoselectivity due to minimal steric differentiation between faces.[26] Catalytic variants using hydrogen peroxide further enable regioselective epoxidation. For instance, the Ga(NO3)3/H2O2 system promotes endocyclic epoxide formation in (R)-carvone when acidic ligands are present, achieving up to 90% selectivity through metal-ligand cooperation that stabilizes the transition state for the conjugated alkene. Manganese-based catalysts with dicarboxylic acids as co-ligands similarly oxidize carvone to epoxides in high turnover numbers (up to 500), with acetic acid favoring the exocyclic product.[27][28] Ozonolysis cleaves carvone's double bonds, with outcomes varying by solvent and conditions. In aprotic media like dichloromethane or protic media like methanol with pyridine, the reaction forms stable ozonides that decompose to carbonyl fragments, including formaldehyde from the exocyclic bond and a conjugated enone-aldehyde from the endocyclic bond. Gas-phase ozonolysis yields acetone and 4-oxopentanal as principal products, reflecting cleavage of the isopropenyl group (producing acetone) and ring opening to the linear keto-aldehyde. The reaction proceeds via a Criegee mechanism, with the stereochemistry of carvone enantiomers exerting no influence on product yields. The simplified equation for primary cleavage is: Yields of acetone reach approximately 0.8 mol per mol carvone, highlighting the efficiency of exocyclic bond scission.[29][30] Oxidation with potassium permanganate under mild, cold alkaline conditions effects syn dihydroxylation of the endocyclic double bond, forming carvone-8,9-diol as the major product. More forcing conditions with KMnO4 lead to oxidative cleavage, producing a ketocarboxylic acid (C9H12O3) via ring opening and decarboxylation elements. Hydrogen peroxide under neutral or basic conditions can also generate diols indirectly through epoxide hydrolysis, though epoxides predominate.[31]Conjugate additions and other reactions

Carvone, featuring an α,β-unsaturated ketone moiety, readily undergoes conjugate (1,4-) additions with organocopper reagents, providing a method for stereoselective carbon-carbon bond formation at the β-position. For instance, treatment of (S)-(+)-carvone with lithium dimethylcuprate in ether at low temperature yields 3-methylcarvone as the major product, with high diastereoselectivity favoring the anti adduct due to axial approach of the nucleophile from the face opposite the C5-isopropenyl substituent. This reaction exemplifies the regioselectivity of organocuprates over direct (1,2-) addition, achieving yields around 80% and serving as an educational demonstration of stereocontrol in enone additions.[32] The general conjugate addition proceeds as follows: (with anti selectivity >10:1 diastereomeric ratio). As a dienophile, carvone participates in Diels-Alder cycloadditions with conjugated dienes, leveraging its electron-deficient enone for [4+2] pericyclic reactivity to form bicyclic scaffolds. Reactions with dienes such as isoprene or silyloxybutadienes, often promoted by Lewis acids like BF₃·OEt₂ or AlCl₃, afford endo-selective cycloadducts with facial selectivity controlled by the chiral cyclohexenone framework. A representative example is the Lewis acid-catalyzed union of (R)-(-)-carvone with isoprene, producing a major regioisomer (para orientation) in 60-70% yield, where stereochemistry is dictated by coordination to the carbonyl oxygen and confirmed via 2D NMR. These transformations are valuable for constructing enantiopure decalones and have been applied in natural product syntheses.[33][34] Other notable reactions include the intramolecular [2+2] photocycloaddition of carvone upon UV irradiation (λ > 300 nm) in non-polar solvents, where the triplet excited state of the enone adds across the exocyclic isopropenyl double bond to generate carvonecamphor in quantum yields up to 0.15 under nitrogen. This phototransformation highlights carvone's utility in generating bridged bicyclic ketones. In synthetic routes from limonene, nitrosation with nitrosyl chloride (NOCl) at 0°C regioselectively adds across the endocyclic double bond to form limonene nitrosochloride, which, upon heating in DMF/isopropanol followed by base hydrolysis, eliminates HCl and tautomerizes to carvone in overall yields of 50-60%.[35]Occurrence and biosynthesis

Natural occurrence

Carvone occurs naturally as a monoterpenoid ketone in the essential oils of numerous plants, with its enantiomeric distribution varying by species. The (S)-(+)-enantiomer predominates in caraway (Carum carvi) seeds, where it constitutes 50–75% of the essential oil, which typically comprises 2–7% of the seed's dry weight.[1][36] In spearmint (Mentha spicata) essential oil, the (R)-(-)-enantiomer is the major component, accounting for 55–75% of the oil.[1] Dill seed (Anethum graveolens) oil similarly features the (S)-(+)-enantiomer at levels of 30–65%.[1] Trace quantities of carvone, often less than 1%, appear in other essential oils, including those from peppermint (Mentha piperita), mandarin orange (Citrus reticulata) peel, gingergrass (Cymbopogon martinii), and various citrus varieties.[1] Annual global production of natural carvone is limited, with estimates around 10 tonnes derived primarily from caraway sources.[2] Extraction yields and carvone abundance in caraway exhibit regional variations; for instance, European cultivars frequently show essential oil contents of 4–6% with 50–70% carvone, influenced by soil, climate, and breeding practices.[36]Biosynthesis in plants

Carvone is biosynthesized in plants through a monoterpene pathway originating from geranyl diphosphate (GPP), the universal C10 precursor for monoterpenes derived from the mevalonate or methylerythritol phosphate pathways. In spearmint (Mentha spicata), the pathway proceeds stereospecifically to (R)-(-)-carvone via the action of (-)-limonene synthase, which cyclizes GPP to (4R)-(-)-limonene with high fidelity.[37] Subsequent hydroxylation at the C6 position of (-)-limonene is catalyzed by the cytochrome P450 enzyme limonene-6-hydroxylase (CYP71D18), yielding (-)-trans-carveol as the primary product; this regiospecific monooxygenation requires NADPH and molecular oxygen.[37] The final step involves oxidation of (-)-trans-carveol to (R)-(-)-carvone by (-)-carveol dehydrogenase, an NAD+-dependent enzyme that exhibits strict stereospecificity for the trans isomer and operates optimally at alkaline pH.[37] A parallel biosynthetic route in caraway (Carum carvi) produces the enantiomeric (S)-(+)-carvone, beginning with the cyclization of GPP to (4S)-(+)-limonene by a stereospecific (+)-limonene synthase, achieving over 98% enantiomeric purity.[22] This is followed by C6-hydroxylation of (+)-limonene to (+)-trans-carveol mediated by a distinct cytochrome P450 limonene-6-hydroxylase, which shows high substrate specificity for the (+)-enantiomer and also utilizes NADPH.[22] The pathway concludes with the NAD+-dependent oxidation of (+)-trans-carveol to (S)-(+)-carvone by (+)-carveol dehydrogenase, which prefers the trans configuration and is localized in the secretory structures of developing fruits.[22] These pathways highlight the stereospecificity of key enzymes, with limonene synthases and cytochrome P450 hydroxylases differing between species to dictate the enantiomeric outcome, while the dehydrogenase step ensures efficient conversion to the ketone. In both plants, the enzymes are compartmentalized in glandular trichomes or oil ducts, where monoterpene accumulation occurs during organ development.[22][37]Production

Natural extraction

Carvone is primarily extracted from natural sources through steam distillation of essential oils derived from caraway seeds (Carum carvi) or spearmint leaves (Mentha spicata), where it constitutes a major component.[38][39] In this process, the plant material is subjected to steam, which volatilizes the oil components, allowing their separation from the aqueous phase upon condensation; the resulting essential oil is then collected and dried.[40] This method is preferred due to its ability to preserve the volatile terpenoid structure of carvone without thermal degradation.[41] The essential oil yield from caraway seeds via steam distillation typically ranges from 2% to 6% by weight, with carvone comprising 50% to 70% of the oil, enabling up to 70% recovery of carvone from the distilled oil fraction.[42][38] For spearmint leaves, the oil yield is approximately 0.7%, containing 50% to 70% carvone, often enriched further through optimized distillation variants like microwave-assisted hydro-distillation.[39][43] Following initial distillation, fractional distillation separates carvone from accompanying terpenes such as limonene, exploiting differences in boiling points (carvone boils at 231°C, limonene at 176°C).[44] Vacuum distillation is commonly employed in subsequent purification steps to lower pressures and prevent decomposition, yielding high-purity carvone (often >90%) while maintaining the enantiomeric integrity—S-(+)-carvone from caraway and R-(-)-carvone from spearmint.[45][46] Alternative solvent extraction methods, such as using n-pentane or n-hexane on hydro-distilled herbal residues, can supplement steam distillation to recover additional carvone, particularly for oxygenated terpenes, though they are less common due to solvent residue concerns.[43][41] On a commercial scale, natural production of (S)-(+)-carvone is approximately 10 tonnes per year, primarily from caraway oil, while (R)-(-)-carvone from spearmint oil exceeds 1,500 tonnes annually, to meet demand for flavor and fragrance applications.[47]Synthetic preparation

One prominent synthetic route to (R)-(-)-carvone involves the transformation of (R)-(+)-limonene, readily obtained from orange peels, through a three-step process. First, nitrosyl chloride is added across the trisubstituted double bond of limonene to form limonene nitrosochloride. This intermediate undergoes dehydrohalogenation upon heating to yield carvoxime. Finally, hydrolysis of carvoxime in the presence of oxalic acid as a catalyst produces (R)-(-)-carvone.[48][49] This method, established as an industrial standard by the 1960s, achieves overall yields of 30-35% but generates significant by-products, such as those from Beckman rearrangement of the oxime, posing disposal challenges.[50] For the (S)-(+)-carvone enantiomer, a parallel route utilizes (S)-(-)-limonene as the starting material, following the same nitrosyl chloride addition, dehydrohalogenation, and oxalic acid-catalyzed hydrolysis sequence to afford the desired product. However, (S)-(-)-limonene is less abundant and more costly than its (R) counterpart, limiting scalability. Alternatively, (S)-(+)-carvone can be obtained through resolution of racemic carvone, typically via formation of diastereomeric salts with chiral resolving agents like tartaric acid derivatives, followed by separation and regeneration, or through chromatographic methods on chiral stationary phases. Asymmetric syntheses from achiral precursors, such as enantioselective reductions or cyclizations, have been explored in laboratory settings but are not yet dominant in industrial production due to complexity and cost.[50][49] The sourcing of (R)-(+)-limonene from abundant citrus by-products renders synthetic (R)-(-)-carvone more cost-effective than isolation from natural spearmint oil, with production costs historically around $10 per pound compared to higher prices for the enantiomerically pure natural form. In contrast, synthetic (S)-(+)-carvone remains pricier at approximately $40 per pound, reflecting the scarcity of (S)-limonene and inefficiencies in resolution processes. Major producers, including Formosa in Brazil and Quest in Mexico, leverage these limonene-based routes for annual outputs exceeding 1,000 metric tons combined.[50]Applications

Food and flavoring

Carvone serves as a key flavoring agent in the food industry, where its enantiomers impart distinct sensory profiles to various products. The (S)-(+)-enantiomer, predominant in caraway and dill essential oils, contributes a warm, spicy, herbaceous note characteristic of these seeds, while the (R)-(-)-enantiomer, the primary component of spearmint oil, provides a cool, minty aroma and taste.[16] These properties make (S)-(+)-carvone essential for enhancing dill and caraway flavors in baked goods, condiments, and savory dishes, whereas (R)-(-)-carvone is widely used in spearmint-flavored chewing gum, toothpaste, and oral care products to deliver a refreshing sensation.[2] Carvone holds Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and is assigned FEMA number 2249 by the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association, affirming its safety for use as a flavoring substance in food.[51] Typical usage levels vary by product category; for instance, concentrations range from 34 ppm (usual) to 850 ppm (maximum) in nonalcoholic beverages, 94–116 ppm in baked goods, and up to 20,000 ppm in chewing gum, ensuring effective flavor delivery without overpowering other ingredients.[52] In the food industry, natural carvone is primarily sourced through steam distillation of essential oils from plants like spearmint or caraway, prized for its purity and authentic profile, though it can be limited by seasonal availability and higher costs. Synthetic carvone, produced via chemical synthesis from precursors like limonene, offers a cost-effective alternative with comparable purity levels exceeding 99%, enabling consistent supply for large-scale flavor formulations.[50][53] To maintain quality in natural essential oils used for food flavoring, adulteration—such as the addition of synthetic or petrochemical-derived carvone—is detected using advanced techniques like compound-specific δ¹⁸O stable isotope analysis, which differentiates natural plant-origin isotopes from synthetic ones based on oxygen ratios.[54] This method ensures authenticity, particularly in high-value spearmint oils where (R)-(-)-carvone content is critical for flavor integrity.Agricultural uses

S-(+)-carvone serves as a natural sprout suppressant for stored potatoes, primarily through the commercial product Talent®, which contains high concentrations of the compound derived from caraway oil and is registered for use in the Netherlands. This product has been approved by the European Union for potato storage applications, with authorization extending until July 31, 2034.[55][56] The compound inhibits sprout growth by interfering with cell division processes in potato tubers, notably during wound healing where it prevents the formation of the cambium layer essential for tissue regeneration and sprouting.[57][58] Applications are typically made at intervals during storage, with rates of 300–600 mL of Talent® per tonne, corresponding to approximately 280–550 mg/kg of active S-(+)-carvone, achieving suppression comparable to or better than traditional chemical inhibitors like chlorpropham (CIPC).[59][60] In the United States, S-(+)-carvone is recognized by the EPA as an effective alternative for sprout control in potato storage, particularly valued for its low toxicity and minimal impact on seed viability compared to phased-out synthetics such as CIPC, which was banned in the EU in 2020 due to residue and health risks.[61][62] This natural option reduces environmental persistence and supports sustainable post-harvest management by degrading more readily without leaving harmful residues. Beyond potatoes, carvone-enriched mint oil formulations are applied in agriculture for weed control, where the compound disrupts microtubule structures in target weeds, leading to inhibited germination and growth at low concentrations.[63][64]Insect control and repellents

R-(-)-carvone, the naturally occurring levorotatory enantiomer, has been registered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as a biopesticide specifically for repelling mosquitoes and other biting insects. This approval allows its use in topical products such as lotions, sprays, and wipes, typically at concentrations of 5-10% to provide personal protection against mosquito bites. The EPA's evaluation concluded that l-carvone poses low risk to human health when used as directed, making it a viable natural alternative to synthetic repellents like DEET.[65] Beyond mosquitoes, carvone demonstrates repellent efficacy against ants, cockroaches, and stored-product pests such as weevils and flour beetles. For instance, carvone disrupts the behavior of German cockroaches by deterring their approach in choice assays, while it exhibits toxicity and repellency toward red imported fire ants and grain-infesting beetles like the rice weevil. The primary mechanism involves olfactory disruption, where carvone interacts with insect chemoreceptors, masking attractants or activating avoidance responses through its volatile terpenoid structure. This mode of action enables carvone to create spatial barriers without direct contact toxicity in many cases.[66][67][68] Field and laboratory studies highlight carvone's practical effectiveness, with formulations reducing mosquito landings or bites by 70-90% for 2-4 hours post-application, depending on environmental factors and delivery method. Spearmint oil, rich in R-(-)-carvone, significantly lowered Aedes aegypti attraction in olfactometer tests, achieving near-complete repellency in controlled setups. Carvone is often formulated in essential oil blends with compounds like limonene or thymol to enhance stability and synergistic effects, serving as natural pesticides for household and storage applications. These blends improve persistence and broaden spectrum activity against multiple insect species while maintaining biodegradability.[69][70][71]Biological effects

Metabolism

Carvone undergoes biotransformation primarily in the mammalian liver through cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes, leading to oxidized metabolites that are further conjugated for excretion. The major pathway involves sequential oxidation starting with allylic hydroxylation at the 10-position to form 10-hydroxycarvone, followed by further oxidation to dihydrocarvonic acid (via reduction of the double bond and oxidation of the side chain) and carvonic acid (complete oxidation of the isopropenyl group to a carboxylic acid). These transformations are NADPH-dependent and stereoselective, with CYP450 isoforms such as CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 implicated in humans, while rat liver microsomes show higher activity for certain enantiomers. A minor pathway includes NADPH-dependent reduction of the ketone group to form (-)-carveol, primarily from R-(-)-carvone, with lower yields in human versus rat liver microsomes. The resulting alcohols and acids are conjugated with glucuronic acid via UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, enhancing water solubility for renal excretion; glucuronidation rates are notably higher in rats compared to humans.[72] Key urinary metabolites include dihydrocarvonic acid, carvonic acid, and uroterpenolone (a ring-opened derivative from further degradation), accounting for the majority of excreted dose within 24 hours.[73] In humans, 10-hydroxycarvone is not prominently detected, likely due to rapid further oxidation, whereas it serves as a detectable intermediate in rats and rabbits, highlighting species differences in CYP450 efficiency and metabolite profiles. Carvone exhibits a short plasma half-life of approximately 1-2 hours in humans (2.4 hours specifically for D-carvone), facilitating rapid clearance. The metabolic scheme can be summarized as follows:- Oxidation pathway: Carvone → (CYP450) 10-hydroxycarvone → (further oxidation) dihydrocarvonic acid → carvonic acid → (conjugation) glucuronides (urinary excretion).

- Reduction pathway: Carvone → (NADPH-reductase) (-)-carveol → (glucuronidation) carveol-glucuronide (minor urinary excretion).

- Degradation: Carvonic acid/dihydrocarvonic acid → uroterpenolone (urinary metabolite).[73]