Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

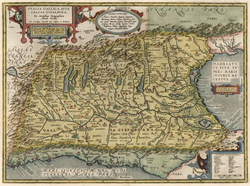

Padania

View on WikipediaPadania (/pəˈdeɪniə/ pə-DAY-nee-ə, UK also /-ˈdɑːn-/ -DAH-,[1] Italian: [paˈdaːnja]) is an alternative name and proposed independent state encompassing Northern Italy, derived from the name of the Po River (Latin Padus), whose basin includes much of the region, centered on the Po Valley (Pianura Padana), the major plain of Northern Italy.

Key Information

Coined in 1903 as a geographical term roughly corresponding to the historically Celtic land of Cisalpine Gaul, the term was popularized beginning in the early 1990s, when Lega Nord, a federalist and, at times, separatist political party in Italy, proposed it as a possible name for an independent state. Since then it has been strongly associated with "Padanian nationalism" and North Italian separatism.[2] Padania as defined in Lega Nord's 1996 Declaration of Independence and Sovereignty of Padania goes beyond Northern Italy and includes much of Central Italy, for a greater Padania that includes more than half of the Republic of Italy (161,000 of 301,000 km2 in area, 34 million out of 60 million in population).

Some Padanians consider themselves to have Celtic ancestry and/or heritage.[3][4]

Etymology

[edit]The adjective padano is derived from Padus, the Latin name of the Po River. The French client republics in the Po Valley during the Napoleonic era included the Cispadane Republic and the Transpadane Republic, according to the custom (emerged with the French Revolution) of naming territories on the basis of watercourses. The ancient Regio XI (the region of the Roman Empire on the current territory of the Aosta Valley, Piedmont and Lombardy) has been referred to as Regio XI Transpadana only in modern historiography.

The terms Pianura Padana or Val Padana are the standard denominations in geography textbooks and atlases, but the derivation Padania was coined back in 1903 and popularized by a Hoepli geographical encyclopedia in 1910.[5]

Journalist Gianni Brera from the 1960s used the term Padania to indicate the area that at the time of Cato the Elder corresponded to Cisalpine Gaul.[6] In the same years and later, the term Padania was considered a geographic synonym of Po Valley and as such was included in the Enciclopedia Universo in 1965[7] and in the Devoto–Oli dictionary of the Italian language in 1971. The term was also used in Italian dialectology, in relation to Gallo-Italic languages, and sometimes even extended to all regional languages distinguishing Northern from Central Italy along the La Spezia–Rimini Line.[8]

Macroregion

[edit]The first use of Padania in socio-economic terms dates from 1975, when Guido Fanti, the Communist President of Emilia-Romagna, proposed a union composed of Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, Lombardy, Piedmont and Liguria.[9][10] The term was seldom used in these terms until the Giovanni Agnelli Foundation re-launched it in 1992 through the volume La Padania, una regione italiana in Europa (English: Padania, an Italian region in Europe), written by various academics.[11]

In 1990 Gianfranco Miglio, a political scientist who would be elected senator for Lega Nord in 1992 and 1994, wrote a book in which he described a draft constitutional reform. According to Miglio, Padania (consisting of five regions: Veneto, Lombardy, Piedmont, Liguria and Emilia-Romagna with the addition of the provinces of Massa-Carrara and Pesaro and Urbino in the Tuscany and Marche regions, respectively) would become one of the three hypothetical macroregions of a future Italy, along with Etruria (Central Italy, without the two aforementioned provinces) and Mediterranea (Southern Italy), while the autonomous regions (Aosta Valley, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Sicily and Sardinia) would be left with their current autonomy.[12]

In political science

[edit]

Gilberto Oneto, a student of Miglio without any academic credentials, in the 1990s researched northern traditions and culture to find evidence of the existence of a common Padanian heritage.[13][14] Historian and linguist Sergio Salvi (2014) has also defended the concept of Padania.[15]

In 1993 Robert D. Putnam, a political scientist at Harvard University, wrote a book titled Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, in which he spoke of a "civic North", defined according to the inhabitants' civic traditions and attitudes, and explained its social peculiarities to the historical emergence of the free medieval communes since the 10th century.[16]

Lega Nord's definition of Padania's boundaries is similar to Putnam's "civic North", which also includes the central Italian regions of Tuscany, Marche and Umbria. Stefano Galli, a political scientist close to the party and columnist for Il Giornale and La Padania, has called Putnam's theory a source for defining Padania.[17] According to Galli, these regions share similar patterns of civil society, citizenship, and government with the North.[18]

The existence of a "Padanian nation" has been however criticised by a number of organisations and individuals in Italy, from the Italian Geographical Society[19] to historian Paolo Bernardini, who is a supporter of Venetian nationalism instead.[20] Angelo Panebianco, a political scientist, once explained that, even though a "Padanian nation" does not exist yet, it might well emerge as all nations are ultimately human inventions.[21]

Padanian nationalism

[edit]Lega Nord, a political party created in 1991 by the union of several northern regional parties (including Lega Lombarda and Liga Veneta), used the term for a larger geographical range than the Po Valley proper, or the macroregion proposed by Fanti in the 1970s.

Since 1991, Lega Nord has promoted either secession or larger autonomy for Padania, and has created a flag and a national anthem to this effect.[22] In 1996, the "Federal Republic of Padania" was proclaimed.[23] Subsequently, in 1997, Lega Nord created an unofficial Padanian parliament in Mantua and organised elections for it. Lega Nord also chose a national anthem: the Va, pensiero chorus from Giuseppe Verdi's Nabucco, in which the exiled Hebrew slaves lament their lost homeland.

The term Padania has been also used in politics by other nationalist/separatist parties and groups, including Lega Padana, Lega Padana Lombardia, the Padanian Union, the Alpine Padanian Union, Veneto Padanian Federal Republic and the Padanian Independentist Movement.[24]

Lega Nord's Padania

[edit]

According to Lega Nord's Declaration of Independence and Sovereignty of Padania,[25] Padania is composed of 14 "nations" (Lombardy, Veneto, Piedmont, Tuscany, Emilia, Liguria, Marche, Romagna, Umbria, Friuli, Trentino, South Tyrol, Venezia Giulia, Aosta Valley), encompassing both Northern and Central Italy and slightly differing from Gianfranco Miglio's project.[12] The current 11 regions of Italy forming Padania, according to the party, are listed below:

| Region | Population (millions, 2016)[26] |

Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|

| Lombardy | 10.0 | 23,865 |

| Veneto | 4.9 | 18,391 |

| Emilia-Romagna (Emilia and Romagna) |

4.5 | 22,451 |

| Piedmont | 4.4 | 25,399 |

| Liguria | 1.6 | 5,422 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia (Friuli and Venezia Giulia) |

1.2 | 7,845 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol (Trentino and South Tyrol) |

1.1 | 13,607 |

| Aosta Valley | 0.1 | 3,263 |

| Northern Italy | 27.7 | 120,243 |

| Tuscany | 3.8 | 22,993 |

| Marche | 1.6 | 9,366 |

| Umbria | 0.9 | 8,456 |

| Padania (total) | 33.9 | 161,076 |

Flag of Padania

[edit]The "Sun of the Alps" is the unofficial flag of Padania and the symbol of the Padanian nationalism. The flag has a green stylized sun on a white background. It resembles ancient ornaments which are found in the art and culture of the area, like one example of Etruscan art from the 7th century BC found at Civitella Paganico.[27] The flag was created in the 1990s and was adopted by Lega Nord upon their declaration of Padanian independence.[28][29]

In its previous version, the flag included a red St George's Cross and a smaller Sun of the Alps in the upper part.[28]

Opinion polling

[edit]While support for a federal system, as opposed to a centrally administered state, receives widespread consensus within Padania, support for independence is less favoured. One poll in 1996 estimated that 52.4% of interviewees from Northern Italy considered secession advantageous (vantaggiosa) and 23.2% both advantageous and desirable (auspicabile).[30][failed verification] Another poll in 2000 estimated that about 20% of "Padanians" (18.3% in North-West Italy and 27.4% in North-East Italy) supported secession in case Italy was not reformed into a federal state.[31][failed verification]

According to a poll conducted in February 2010 by GPG, 45% of Northerners support the independence of Padania.[32] A poll conducted by SWG in June 2010 puts that figure at 61% of Northerners (with 80% of them supporting at least federal reform), while noting that 55% of Italians consider Padania as only a political invention, against 42% believing in its real existence (45% of the sample being composed of Northerners, 19% of Central Italians and 36% of Southerners). As for federal reform, according to the poll, 58% of Italians support it.[33][34] A more recent poll by SWG puts the support for fiscal federalism and secession respectively at 68% and 37% in Piedmont and Liguria, 77% and 46% in Lombardy, 81% and 55% in Triveneto (comprising Veneto), 63% and 31% in Emilia-Romagna, 51% and 19% in Central Italy (not including Lazio).[35]

In business

[edit]- Cassa Padana, Italian cooperative bank

- Banca Centropadana, Italian cooperative bank

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Padania"[dead link] (US) and "Padania". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ Squires, Nick (2011-08-23). "Silvio Berlusconi ally says Italy 'condemned to death'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ Wills, Matthew (2019-06-19). "What Does It Mean To Be Celtic?". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ DONADIO, RACHEL. "As Italy Government Totters, a New Power Broker Rises". Wilmington Star-News. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Gian Lodovico Bertolini, Sulla permanenza del significato estensivo del nome di Lombardia, Rome, 1903, "Bollettino della Società geografica italiana", volume XXXVII, pp. 345-349.

- ^ Brera, Gianni (1993). Storie dei Lombardi. Milan: Baldini & Castoldi. p. 421. ISBN 88-85989-27-6.. Brera, Gianni. "Invectiva ad Patrem Padum". Guerin Sportivo. Milan.

- ^ "Italia". Enciclopedia Universo – vol. VII. Novara: De Agostini. 1965. pp. 196–197.

- ^ Hull, Geoffrey, PhD thesis 1982 (University of Sydney), published as The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language. 2 vols. Sydney: Beta Crucis, 2017.

- ^ Santini, Francesco (1975-11-06). "Fanti spiega la sua proposta per una grande "lega del Po"". Turin: La Stampa.

- ^ "Addio a Guido Fanti, inventore della "Lega del Po"". Milan: L'Indipendenza. 2012-02-12. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13.

- ^ Bracalini, Paolo (25 June 2010). "La Padania? L'ha inventata la Fondazione Agnelli". Milan: il Giornale.

- ^ a b Miglio, Gianfranco (1990). Una Costituzione per i prossimi trent'anni. Intervista sulla terza Repubblica. Rome-Bari: Laterza. ISBN 88-420-3685-4.

- ^ Oneto, Gilberto (1994). Bandiere di libertà: Simboli e vessilli dei Popoli dell'Italia settentrionale. Florence: Alinea.

- ^ Oneto, Gilberto (1997). L'invenzione della Padania. Ceresola: Foedus.Oneto, Gilberto (2010). Il sole delle Alpi. Mito, storia e realtà di un simbolo antico. Turin: Il Cerchio.Oneto, Gilberto (2012). Polentoni o padani? Apologia di un popolo di egoisti xenofobi ignoranti ed evasori. Turin: Il Cerchio. La Libera Compagnia Padana

- ^ Viva La Grande Nazione Catalana E Anche Quella Padana | L'Indipendenza Archived 2014-01-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Guiso, Luigi; Sapienza, Paola; Zingales, Luigi (2016). "Long-Term Persistence". Journal of the European Economic Association. 14 (6): 1401–1436. doi:10.1111/jeea.12177. hdl:1814/9290.

- ^ Galli, Stefano (2011-03-28). "Il commento Fini si rassegni, la Padania esiste davvero". Milan: il Giornale.

- ^ Riotta, Gianni (1993-02-12). "L'Italia fatta a pezzi". Milan: Corriere della Sera.

- ^ Rapporto annuale 2010

- ^ [1] Archived November 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ La questione non e' padana - Corriere della Sera

- ^ Oneto, Gilberto (1997). L'invenzione della Padania. Berbenno: Foedus Editore.

- ^ Francesco Jori, Dalla Łiga alla Lega. Storia, movimenti, protagonisti, Marsilio, Venice 2009, p. 103

- ^ Jori, Francesco (2009). Dalla Łiga alla Lega. Storia, movimenti, protagonisti. Venice: Marsilio.

- ^ Lega Nord (15 September 1996). "Dichiarazione di indipendenza e sovranità della Padania" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2006.

- ^ istat.it (2016) Archived 2017-11-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Archeologia: ...in Toscana" (in Italian).

- ^ a b Araldica e Bandiere della Federazione Padana Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, Angelo Veronesi.

- ^ Movimento Giovani Padani (ed.). "Dichiarazione di indipendenza e sovranità della Padania". Archived from the original on 2013-05-12.

- ^ Diamanti, Ilvo (1 January 1996). "Il Nord senza Italia?". Limes. L'Espresso.

- ^ L'Indipendente, 23 August 2000.

- ^ GPG (2009-02-12). "I sondaggi di GPG: Simulazione Referendum - Nord Italia". Il-liberale.blogspot. Archived from the original on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ SWG (2010-06-25). "Federalismo e secessione" (PDF). Affaritaliani. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

- ^ SWG (2010-06-28). "Gli italiani non credono nella Padania. Ma al Nord prevale il sì alla secessione". Affaritaliani.

- ^ GPG (2011-05-25). "Sondaggi GPG: Quesiti/2 - Maggio 2011". ScenariPolitici.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Diamanti, Ilvo (1996). Il male del Nord. Lega, localismo, secessione. Rome: Donzelli Editore. ISBN 88-7989-268-1.

- Gomez-Reino Cachafeiro, Margarita (2002). Ethnicity and Nationalism in Italian Politics. Inventing the Padania: Lega Nord and the Northern Question. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-1655-X.

- Hull, Geoffrey (2017). The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language. 2 vols. Sydney: Beta Crucis Editions. ISBN 978-1-64007-053-0.

- Huysseune, Michel (2006). Modernity and secession. The social sciences and the political discourse of the Lega Nord in Italy. Oxford: Berg Publishers. ISBN 1-84545-061-2.

- Mainardi, Roberto (1998). L'Italia delle regioni. Il Nord e la Padania. Milan: Bruno Mondadori. ISBN 88-424-9442-9.

External links

[edit]Padania

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Geography

Etymology

The name Padania derives from Padus, the Latin designation for the Po River, which spans 652 kilometers and forms the core of northern Italy's expansive alluvial plain, historically referred to in Italian as Pianura Padana.[8] This etymological root reflects the river's central role in shaping the region's hydrology, agriculture, and settlement patterns since antiquity.[9] While the adjective padano has long described features of the Po Valley in geographical contexts, the noun Padania saw limited pre-modern usage and was revived in the 20th century, notably by journalist Gianni Brera to evoke the cultural and economic cohesion of the northern plains.[9] In the political sphere, Lega Nord leader Umberto Bossi popularized Padania from the early 1990s onward as a symbol of northern Italian autonomy, transforming the term from a descriptive label into a marker of proposed national identity distinct from southern Italy.[6] This adoption leveraged the ancient hydrological reference to underscore claims of historical self-sufficiency, though critics argue it constructs a novel ethnic narrative unsupported by continuous historical precedent.[10]Territorial Boundaries and Macroregion Characteristics

The territorial boundaries of Padania, as conceptualized by the Lega Nord, primarily encompass the northern Italian regions drained by the Po River basin, including Piedmont, Lombardy, Veneto, Liguria, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, and Trentino-Alto Adige.[6] This area extends from the Alps in the north to the Apennine Mountains in the south, aligning with the historical and geographical notion of the Po plain, known in Latin as Padania.[7] Variations in definitions occasionally incorporate central regions such as Tuscany, Umbria, and Marche, reflecting broader interpretations of a "civic North" with shared economic and cultural traits.[11] Geographically, the macroregion is dominated by the Po Valley, Italy's largest alluvial plain, spanning approximately 46,000 square kilometers and supporting a dense network of rivers and canals that facilitate irrigation and transport.[12] The terrain transitions from mountainous borders—Alps to the north and Apennines to the southeast—to flat, fertile lowlands ideal for agriculture, including rice, wheat, and dairy production, which have historically driven regional prosperity since medieval land reclamation efforts.[13] Climatically, the area experiences a humid subtropical to continental influence, with mild winters and hot summers, though prone to fog and air pollution from intensive human activity.[14] Economically, Padania functions as Italy's primary industrial and manufacturing hub, generating over 50% of the national GDP through sectors like mechanical engineering, fashion, automotive, and agribusiness, with the Po basin alone contributing around 738 billion euros in output as of recent assessments.[12] This macroregion's competitive edge stems from its integration of advanced infrastructure, skilled labor, and export-oriented firms, contrasting sharply with southern Italy's lower productivity and higher unemployment rates, a divergence exacerbated post-unification by differential state investments and geographical advantages like proximity to European markets.[15] Demographically, it hosts about 25 million residents in compact urban centers like Milan, Turin, and Venice, fostering high per capita income levels exceeding 30,000 euros annually in core provinces.[16]Historical Context

Pre-Unification Regionalism

In the 12th century, northern Italian city-states formed the Lombard League in 1167 to resist the centralizing efforts of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, who sought to reassert imperial authority over the communes. This alliance, comprising cities such as Milan, Venice, Bologna, and Verona, defended municipal autonomy through military victories, including the decisive Battle of Legnano in 1176. The resulting Peace of Constance in 1183 granted the league's members significant self-governance, including control over taxation and local laws, exemplifying early regionalist pushback against external domination in the Po Valley area.[17][18] During the Renaissance and early modern period, northern Italy consisted of fragmented yet autonomous polities, including the maritime Republic of Venice, which maintained independence from 697 until its conquest by Napoleon in 1797, and the Duchy of Milan, which oscillated between local dynasties like the Sforza and foreign Habsburg rule after 1535. These entities developed distinct economic systems—Venice through trade and naval power, Milan via manufacturing and agriculture—reinforcing local identities tied to urban centers rather than a unified northern polity. Competition among states, such as wars between Milan and Venice, underscored regional rivalries over any pan-northern solidarity, with autonomy preserved through diplomatic balances against imperial or papal interference.[19] In the lead-up to unification, 19th-century northern intellectuals articulated regionalist visions through federalism, advocating decentralized governance to safeguard local liberties against monarchical centralism. Carlo Cattaneo, a Lombard patriot and defender of Milan during the 1848 Five Glorious Days uprising against Austrian rule, promoted a federal republic of Italian regions, arguing in works like Dell'insurrezione di Milano (1848) that unity should emerge from autonomous communes rather than Piedmontese imposition. This contrasted with Camillo Cavour's unitary model, highlighting tensions between northern preferences for subsidiarity and the eventual centralized Kingdom of Italy proclaimed in 1861.[20]Post-1861 North-South Economic Divergence

Following the political unification of Italy in 1861, economic disparities between the northern regions—encompassing the Po Valley and areas associated with later Padanian identity—and the southern Mezzogiorno intensified, transforming pre-existing differences into a persistent structural divide. At unification, per capita income in the North-West stood approximately 25% higher than in the South, with northern real wages exceeding southern levels by 15% overall and up to 20% when excluding the islands. These gaps, rooted in antecedent conditions such as higher northern urbanization and proto-industrial activity, widened as the North pursued industrialization while the South stagnated in agrarian patterns. By 1871, southern GDP per capita ranged from 87% to 90% of the national average, compared to 108%–114% in the North-West; this ratio deteriorated to 78%–90% in the South by 1891, against 113%–141% in the North-West.[21][22][23] The North's economic ascent accelerated from the 1880s onward, fueled by the "industrial triangle" of Lombardy, Piedmont, and Liguria, where sectors like textiles, mechanics, and chemicals expanded rapidly due to access to water resources, skilled labor, and European markets. Annual GDP growth in the North outpaced the South, with northern rates reaching 1.05% from 1891 to 1901 compared to lower southern figures, culminating in the North-West's GDP per capita at 141% of the national average by 1911, while the South hovered at 85%. Southern backwardness persisted amid large latifundia systems, inefficient land tenure, and widespread brigandage from 1861 to 1870, which necessitated heavy military expenditures—over 100,000 troops deployed—that diverted resources from development and entrenched absentee landlordism. Literacy rates, a proxy for human capital, underscored the divide: southern illiteracy exceeded 85% at unification, correlating with subdued real wage growth, whereas northern investments in public education supported productivity gains; econometric analysis attributes up to 3.7 percentage points of wage divergence to literacy shifts from southern lows (e.g., 8.3% in Caltanissetta) to northern highs (e.g., 57.7% in Turin).[23][22][23] Institutional legacies amplified these trends: northern regions, influenced by Habsburg reforms emphasizing local autonomy and commerce, contrasted with the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies' centralized absolutism, which stifled entrepreneurship and fostered clientelism. Post-unification policies exacerbated imbalances, as railway construction prioritized the North—by 1880, over 60% of Italy's 9,000 km of track lay north of Rome—enhancing northern market integration while southern infrastructure lagged. Fiscal unification imposed a progressive tax burden heavier on the North's emerging wealth, yet expenditures skewed toward military suppression in the South rather than productive investments, sowing seeds of northern fiscal resentment without alleviating southern inefficiencies like emerging organized crime networks that undermined property rights and investment. Revisionist views attributing southern decline solely to unification-era disruptions lack support, as real wage data show no abrupt post-1861 collapse but gradual divergence driven by endogenous factors like human capital deficits.[22][23][22]Origins of Padanian Nationalism

Formation of Lega Nord (1989-1991)

The formation of Lega Nord began in late 1989 amid growing regionalist sentiments in northern Italy, where local autonomist parties sought to challenge the centralized Italian state amid economic grievances over fiscal redistribution to the south. Umberto Bossi, leader of the Lega Lombarda—founded in 1984 to advocate Lombard autonomy—initiated coordination among several northern leagues, including the Liga Veneta, Union Piemontese, and others from Emilia-Romagna and Liguria. These groups, rooted in post-World War II federalist ideas and 1980s local protests against national bureaucracy, formed the Alleanza Nord electoral cartel for the June 1989 European Parliament elections, securing approximately 1.23% of the national vote (or 4.67% in the north) and electing one MEP.[24][25] Throughout 1990, negotiations intensified to transform this loose alliance into a unified party, driven by shared demands for fiscal federalism, devolved powers, and resistance to perceived parasitism from southern regions reliant on northern tax contributions. Bossi, leveraging his charisma and anti-establishment rhetoric, consolidated leadership by absorbing smaller movements and marginalizing rivals, such as Venetian leader Franco Rocchetta. By early 1991, six regional leagues merged formally into Lega Nord on January 8, establishing it as a single entity headquartered in Milan under Bossi's presidency.[26][24] The party's statutes emphasized northern unity, with initial platforms calling for a federal Italy or, failing that, enhanced regional sovereignty to retain local wealth generated by industrial heartlands like Lombardy and Veneto.[25] This merger marked a shift from fragmented localism to a cohesive northern identity, though internal tensions over centralization under Bossi persisted. Early Lega Nord campaigns highlighted empirical disparities, such as northern per capita GDP exceeding southern levels by factors of 1.5 to 2 times in the late 1980s, framing unification-era policies as causal drivers of inefficiency and resentment. The party's rapid organizational growth—claiming over 100,000 members by mid-1991—reflected grassroots support from small business owners and workers alienated by national parties' corruption scandals.[27][26]Early Ideological Foundations

The early ideological foundations of Padanian nationalism emerged from disparate regionalist initiatives in northern Italy during the late 1970s and 1980s, driven by grievances over centralized fiscal policies that channeled northern-generated wealth southward via mechanisms like the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno, established in 1950 to fund southern infrastructure but criticized for inefficiency and clientelism. Movements such as the Movimento Autonomista Bergamasco, founded in 1975, advocated for devolved powers to local communities, emphasizing self-governance, defense of provincial economies dominated by small and medium enterprises, and resistance to national parties' dominance, which were seen as extracting resources without reciprocal benefits.[28] These groups invoked medieval precedents like the 12th-century Lombard League, a confederation of northern cities that resisted imperial overreach, to legitimize demands for autonomy rooted in historical federalist traditions rather than unitary statehood imposed after 1861.[25] Umberto Bossi formalized these currents with the founding of the Lega Lombarda on April 12, 1984, positioning it as a vehicle for Lombard-specific identity against "Roman" centralism, with core tenets including fiscal sovereignty to halt interregional transfers—estimated at 20-25% of northern GDP in the 1980s—and promotion of local dialects and customs as bulwarks against cultural homogenization.[26] [29] Bossi's rhetoric, shaped by his prior affiliation with the Italian Communist Party, initially framed the struggle in anti-system terms, decrying partitocrazia (party rule) and bureaucratic parasitism while rejecting both traditional left-wing statism and right-wing nationalism, though it incorporated populist appeals to northern work ethic versus southern dependency.[30] This platform gained traction amid Tangentopoli's precursors, with early manifestos highlighting empirical data on per capita income disparities—northern regions averaging 15,000-20,000 lire daily wages by 1985 versus southern figures half that—causally linking them to redistributive policies that disincentivized productivity.[31] A nascent ethnic-cultural layer distinguished northerners as descendants of pre-Roman Celtic tribes in the Po basin (Gallia Cisalpina), contrasting their purported communal, decentralized ethos with the hierarchical "Latin" south, though this was more rhetorical than programmatic in the 1980s and served to underscore causal realism in regional divergence rather than biological determinism.[32] [33] By the late 1980s, as regional leagues federated toward what became Lega Nord, the ideology synthesized economic realism—rooted in post-war industrialization creating northern GDP contributions of over 50% to Italy's total—with anti-elite populism, laying groundwork for broader "Padanian" unification without yet formalizing secession.[34] Academic analyses note these foundations prioritized verifiable fiscal imbalances over invented traditions, though later amplifications risked mythological overreach.[35]Development and Peak (1990s-2000s)

Declaration of Independence (1996)

On September 15, 1996, Umberto Bossi, founder and leader of Lega Nord, unilaterally proclaimed the independence of Padania from Italy during a rally in Venice.[36] [37] The event took place on the final day of a three-day gathering organized by the party, attended by an estimated 10,000 to tens of thousands of supporters.[38] [39] As part of the ceremony, aides lowered the Italian flag and raised the green-and-white Padanian standard featuring the Sun of the Alps emblem.[36] The formal document, titled Declaration of Independence and Sovereignty of Padania, was read aloud by Bossi from the steps of the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari.[39] It opened with the assertion: "We, the peoples of Padania, solemnly proclaim Padania an independent and sovereign federal republic."[37] The declaration invoked the right to self-determination, citing historical, cultural, and economic distinctions between northern Italy and the rest of the country, while framing Padania as encompassing regions from Val d'Aosta to Romagna.[39] This act followed Lega Nord's electoral gains earlier that year, where the party secured 10.1% of the national vote, translating to 59 deputies and 27 senators in parliament.[36] Italian authorities treated the proclamation as symbolic rather than a genuine legal challenge, with no arrests or violent clashes reported; police maintained order throughout the event.[40] President Oscar Luigi Scalfaro publicly warned against secessionist rhetoric the day prior, emphasizing national unity.[38] The declaration did not lead to any institutional separation or territorial control, serving primarily as a publicity maneuver to amplify demands for fiscal autonomy and federal reforms amid ongoing north-south economic disparities.[38] [39] In subsequent years, Lega Nord moderated its stance, pivoting toward federalist proposals within Italy's framework rather than outright independence.[36]Federalist Campaigns and Reforms

Following the 1996 declaration of Padanian independence, which Italian courts deemed unconstitutional, Lega Nord leaders pragmatically redirected efforts toward federalist reforms, viewing them as a viable path to northern autonomy within Italy's framework.[41] This involved public mobilization, including rallies and petitions in Lombardy and Veneto to highlight fiscal transfers burdening productive northern regions, alongside parliamentary bills demanding devolution of powers in health, education, and taxation.[11] A pivotal reform influenced by these pressures was the 2001 constitutional amendment to Title V (Law No. 3 of October 18, 2001), which expanded regional legislative competencies, abolished provincial provinces' intermediate role in some areas, and reinforced subsidiarity, enabling regions to enact laws on residual matters not reserved to the state.[42] Though enacted by the center-left government, it aligned with Lega Nord's pre-1996 federalist platform and responded to northern discontent with centralization.[43] In the 2001–2006 center-right coalition, Umberto Bossi, as Minister for Institutional Reforms and Devolution, advanced the 2004 Devolution Bill (S. 1723), seeking to devolve exclusive competencies over health, education, and police to ordinary-statute regions while extending special autonomy models northward; the measure passed the Chamber of Deputies but stalled in the Senate amid southern opposition fearing resource diversion.[44] The subsequent 2005–2006 constitutional package, incorporating federalist elements like bicameral asymmetry and enhanced regional fiscal powers, failed a June 2006 referendum, with 61.26% voting against amid low turnout of 53.72%.[24] Renewed campaigns in the 2008–2011 government culminated in fiscal federalism advancements under Roberto Calderoli, Lega Nord's Minister for Legislative Simplification. Law No. 42 of May 5, 2009, delegated the executive to enact decrees realizing Article 119 of the Constitution, mandating tax assignments tied to regional expenditure needs, standardized cost accounting, and reduced equalization distortions—principles aimed at rewarding northern productivity while curbing clientelistic spending.[45] [46] Implementing decrees followed, including Decree-Law 78/2010 on fiscal responsibility, though political shifts and judicial reviews limited full realization, preserving central overrides in revenue sharing.[47] These efforts underscored Lega Nord's strategy of incremental devolution over secession, yielding measurable gains in regional leverage despite incomplete federal transformation.[48]Symbols and Cultural Identity

Flag, Anthem, and Emblems

The flag of Padania features a white field with a central green emblem known as the Sun of the Alps, a circular symbol composed of six petals enclosed by a ring.[6] This design was adopted by the Lega Nord party in the 1990s as part of its promotion of Padanian independence, lacking direct historical precedents in northern Italian heraldry and instead representing a modern invention tied to regionalist aspirations.[6] Variations exist, such as proposals incorporating elements from Byzantine imperial flags, but the white banner with the green Sun of the Alps remains the most commonly associated version used in Lega Nord rallies and symbolism.[49] The Sun of the Alps serves as Padania's primary emblem, depicted as a geometric ornament with six radiating petals within a bordering ring, often rendered in green to evoke alpine landscapes and Celtic-inspired motifs found in prehistoric rock carvings.[6] Proponents of Padanian nationalism, including Lega Nord, attribute pre-Christian origins to the symbol, linking it to ancient northern European sun wheels, though its contemporary use stems from the party's efforts to forge a distinct regional identity in the 1990s. The emblem appears on flags, seals, and party materials, symbolizing unity and autonomy for the proposed territory encompassing the Po Valley and surrounding areas.[6] Padania's proposed anthem is "Va, pensiero," the chorus from Act III of Giuseppe Verdi's opera Nabucco (1842), which depicts the Hebrew slaves' lament for their lost homeland and has been interpreted as evoking themes of exile and yearning for self-determination.[50] Lega Nord selected this piece in the 1990s to underscore Padanian cultural distinctiveness, performing it at the 1996 declaration of independence in Venice and incorporating it into political events as an unofficial hymn.[51] The choice reflects Verdi's northern Italian roots in Busseto, near Parma, and the aria's historical role as a Risorgimento symbol repurposed for regional rather than national unification narratives.[52]Promotion of Padanian Distinctiveness

The Lega Nord promoted Padanian distinctiveness by invoking the region's ancient Celtic heritage, referencing its designation as Cisalpine Gaul under Roman rule to differentiate it from the Latin south.[10] This narrative emphasized pre-Roman ethnic roots and warrior traditions, often through party rhetoric and symbolic appropriations despite archaeological contestations.[53] [54] Cultural identity-building included high-profile events such as the September 1996 "march on the Po," where thousands gathered near Venice for the unilateral declaration of Padanian independence, featuring flags, anthems, and memorabilia sales to cultivate a sense of nationhood.[55] [38] Annual rallies at Pontida, evoking the 1167 Lombard League's oath against imperial overreach, reinforced narratives of northern autonomy and resistance.[56] Lega Nord leaders contrasted Padanian values of industriousness and self-reliance with southern stereotypes of dependency, framing the north as economically burdened by national unity.[57] To bolster linguistic separation, the party portrayed northern Gallo-Italic dialects as endangered minority languages distinct from standard Italian, advocating their recognition to legitimize Padanian sovereignty claims.[58] Landscapes like the Alps were invoked as natural barriers symbolizing cultural isolation from Mediterranean influences.[53]Economic and Fiscal Arguments

Empirical Evidence of North-South Imbalances

Northern Italian regions, encompassing the core of the proposed Padania territory, demonstrate substantially higher gross domestic product (GDP) per capita than southern regions. In 2021, the GDP per capita in the North-East macro-region reached approximately €36,800, while in the South it stood at €18,900, reflecting a persistent gap where southern levels hover around 50-60% of northern figures.[59] This disparity has widened over time; from 2000 to 2021, northern per capita GDP grew by about 15%, compared to negligible or negative growth in the South, exacerbating the divide to levels where southern GDP per capita equates to roughly 58% of the Center-North average.[60] Fiscal imbalances further underscore these differences, with northern regions acting as net contributors to Italy's central budget while southern regions are net recipients. Empirical reconstructions of net fiscal flows from 1951 to 2010 reveal that southern macro-regions received transfers equivalent to 4-7% of their GDP annually, funded disproportionately by northern tax revenues, amounting to over €100 billion in annual redistribution in recent decades.[61] Quantitative models attribute more than 70% of the north-south income gap to such inter-regional transfers combined with productivity variances, as northern fiscal outflows reduce incentives for local efficiency while subsidizing southern public spending.[62] Unemployment rates amplify the economic chasm, with southern levels consistently double or triple those in the north. In 2023, unemployment averaged 4-5% in northern regions like Lombardy, versus 12-15% in southern areas such as Campania and Sicily, where employment rates for ages 20-64 fall below 50%—the lowest in the European Union.[63] Productivity metrics reinforce this, as northern labor productivity exceeds southern by 40-50%, driven by higher industrialization, skilled workforce density, and infrastructure investment, with southern output per worker lagging due to structural inefficiencies and lower capital intensity.[64] These indicators, drawn from official national accounts, highlight causal factors like divergent historical development paths and policy-induced resource allocation rather than temporary fluctuations.[65]| Key Economic Indicator (2021-2023 averages) | Northern Regions (e.g., Lombardy, Veneto) | Southern Regions (e.g., Calabria, Sicily) | Gap Ratio (South/North) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita (€) | 35,000-38,000 | 17,000-20,000 | ~0.55 |

| Unemployment Rate (%) | 4-6 | 12-18 | ~3x |

| Labor Productivity (index, North=100) | 100 | 60-70 | ~0.65 |

| Net Fiscal Balance (% regional GDP) | +5 to +8 (contributor) | -10 to -15 (recipient) | N/A |