Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Divisionism

View on Wikipedia

Divisionism, also called chromoluminarism, is the characteristic style in Neo-Impressionist painting defined by the separation of colors into individual dots or patches that interact optically.[1][2]

By requiring the viewer to combine the colors optically instead of physically mixing pigments, Divisionists believed that they were achieving the maximum luminosity scientifically possible. Georges Seurat founded the style around 1884 as chromoluminarism, drawing from his understanding of the scientific theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood and Charles Blanc, among others. Divisionism developed along with another style, Pointillism, which is defined specifically by the use of dots of paint and does not necessarily focus on the separation of colors.[1][3]

Theoretical foundations and development

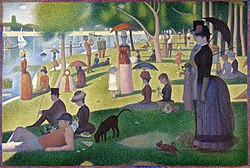

[edit]| A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Georges Seurat |

| Year | 1884–1886 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 207.6 cm × 308 cm (81.7 in × 121.3 in) |

| Location | Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago |

| Portrait of Félix Fénéon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Paul Signac |

| Year | 1890 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 73.5 cm × 92.5 cm (28.9 in × 36.4 in) |

| Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

| Self-Portrait with Felt Hat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1888 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 44 cm × 37.5 cm (17.3 in × 14.8 in) |

| Location | Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam |

| La danse, Bacchante | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Jean Metzinger |

| Year | 1906 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 73 cm × 54 cm (28.7 in × 21.2 in) |

| Location | Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, Netherlands |

| L'homme à la tulipe (Portrait de Jean Metzinger) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Robert Delaunay |

| Year | 1906 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 72.4 cm × 48.5 cm (28.5 in × 19.1 in) |

Divisionism is the technique of painting separate dots or patches of different colors in close proximity that interact optically in the viewer's perception to generate more luminous colors. The paints are not actually mixed but viewed close together, so the separate colors of light reflected by the paints mixes in the eye and brain; the process is called additive mixing[4] and is also used by computer monitors.[5] This is different from mixing different paints together to produce a new color by subtractive mixing,[6] which is also how laser printers produce colors.[5] Despite the theory, Seurat's paintings don't actually use true additive mixture, since the colors reflected by his paints as he used them don't actually mix in the eye. Instead, Seurat used highly contrasting colors in close proximity, but not close enough to mix additively; this effect is called simultaneous contrast, which creates a mild shimmering appearance and slightly increases the colors' apparent visual intensity.[4][7]

Impressionism originated in France in the 1870s, and is characterized by the use of quick, short, broken brushstrokes to accurately capture the momentary effects of light and atmosphere in an outdoor scene. The Impressionists sought to create an "impression" of a momentary scene as perceived by the viewer, rather than a mechanically precise replication of the scene. Divisionism, also known as Pointillism, developed from Impressionism in the 1880s. The Divisionists used a technique of placing small, distinct dots of color next to one another on the canvas, rather than mixing the colors on the palette. This created a more vibrant and dynamic effect, but also required a higher level of skill and precision. Neo-Impressionism emerged in the late 19th century, used more precise and geometric shapes to build compositions and was strongly influenced by the scientific study of color theory and optical color effects, to create a more harmonious and luminous painting.[8][9][10][11]

Scientists or artists whose theories of light or color had some impact on the development of Divisionism include Charles Henry, Charles Blanc, David Pierre Giottino Humbert de Superville, David Sutter, Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood and Hermann von Helmholtz.[2]

Beginnings with Georges Seurat

[edit]Divisionism, along with the Neo-Impressionism movement as a whole, found its beginnings in Georges Seurat's masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Seurat had received classical training at the École des Beaux-Arts, and, as such, his initial works reflected the Barbizon style. In 1883, Seurat and some of his colleagues began exploring ways to express as much light as possible on the canvas.[12] By 1884, with the exhibition of his first major work, Bathers at Asnières, as well as croquetons of the island of Île de la Jatte, his style began taking form with an awareness of Impressionism, but it was not until he finished La Grande Jatte in 1886 that he established his theory of chromoluminarism. In fact, La Grande Jatte was not initially painted in the Divisionist style, but he reworked the painting in the winter of 1885–86, enhancing its optical properties in accordance with his interpretation of scientific theories of color and light.[13]

Paul Signac and other artists

[edit]Color theory

[edit]Charles Blanc's Grammaire des arts du dessin introduced Seurat to the theories of color and vision that would inspire chromoluminarism. Blanc's work, drawing from the theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul and Eugène Delacroix, stated that optical mixing would produce more vibrant and pure colors than the traditional process of mixing pigments.[12] Mixing pigments physically is a subtractive process with cyan, magenta and yellow being the primary colors. On the other hand, if colored light is mixed together, an additive mixture results, a process in which the primary colors are red, green and blue.

In Divisionist color theory, artists interpreted the scientific literature through making light operate in one of the following contexts:[12]

- Local color

- As the dominant element of the painting, local color refers to the true color of subjects, e.g. green grass or blue sky.

- Direct sunlight

- As appropriate, yellow-orange colors representing the sun's action would be interspersed with the natural colors to emulate the effect of direct sunlight.

- Shadow

- If lighting is only indirect, various other colors, such as blues, reds and purples, can be used to simulate the darkness and shadows.

- Reflected light

- An object that is adjacent to another in a painting could cast reflected colors onto it.

- Contrast

- To take advantage of Chevreul's theory of simultaneous contrast, contrasting colors might be placed in close proximity.

Seurat's theories intrigued many of his contemporaries, as other artists seeking a reaction against Impressionism joined the Neo-Impressionist movement. Paul Signac, in particular, became one of the main proponents of divisionist theory, especially after Seurat's death in 1891. In fact, Signac's book, D’Eugène Delacroix au Néo-Impressionnisme, published in 1899, coined the term Divisionism and became widely recognized as the manifesto of Neo-Impressionism.[3]

Divisionism in France and Northern Europe

[edit]In addition to Signac, other French artists, largely through associations in the Société des Artistes Indépendants, adopted some Divisionist techniques, including Camille and Lucien Pissarro, Albert Dubois-Pillet, Charles Angrand, Maximilien Luce, Henri-Edmond Cross and Hippolyte Petitjean.[13] Additionally, through Paul Signac's advocacy of Divisionism, an influence can be seen in some of the works of Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay and Pablo Picasso.[13][14]

In 1907 Metzinger and Delaunay were singled out by the critic Louis Vauxcelles as Divisionists who used large, mosaic-like 'cubes' to construct small but highly symbolic compositions.[15] Both artists had developed a new sub-style that had great significance shortly thereafter within the context of their Cubist works. Piet Mondrian, Jan Sluijters and Leo Gestel, in the Netherlands, developed a similar mosaic-like Divisionist technique circa 1909. The Futurists later (1909–1916) would adapt the style, in part influenced by Gino Severini's Parisian experience (from 1907), into their dynamic paintings and sculpture.[16]

Divisionism in Italy

[edit]The influence of Seurat and Signac on some Italian painters became evident in the First Triennale in 1891 in Milan. Spearheaded by Grubicy de Dragon, and codified later by Gaetano Previati in his Principi scientifici del divisionismo of 1906, a number of painters mainly in Northern Italy experimented to various degrees with these techniques.

Pellizza da Volpedo applied the technique to social (and political) subjects; in this he was joined by Morbelli and Longoni. Among Pellizza's Divisionist works were Speranze deluse (1894) and Il sole nascente (1904).[17] It was, however, in the subject of landscapes that divisionism found strong advocates, including Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, Angelo Morbelli and Matteo Olivero. Further adherents in painting genre subjects were Plinio Nomellini, Rubaldo Merello, Giuseppe Cominetti, Camillo Innocenti, Enrico Lionne and Arturo Noci. Divisionism was also in important influence in the work of Futurists Gino Severini (Souvenirs de Voyage, 1911); Giacomo Balla (Arc Lamp, 1909);[18] Carlo Carrà (Leaving the scene, 1910); and Umberto Boccioni (The City Rises, 1910).[1][19][20]

Criticism and controversy

[edit]Divisionism quickly received both negative and positive attention from art critics, who generally either embraced or condemned the incorporation of scientific theories in the Neo-Impressionist techniques. For example, Joris-Karl Huysmans spoke negatively of Seurat's paintings, saying "Strip his figures of the colored fleas that cover them, underneath there is nothing, no thought, no soul, nothing".[21] Leaders of Impressionism, such as Monet and Renoir, refused to exhibit with Seurat, and even Camille Pissarro, who initially supported Divisionism, later spoke negatively of the technique.[21]

While most divisionists did not receive much critical approval, some critics were loyal to the movement, including notably Félix Fénéon, Arsène Alexandre and Antoine de la Rochefoucauld.[14]

Scientific misconceptions

[edit]Although Divisionist artists strongly believed their style was founded in scientific principles, some people believe that there is evidence that Divisionists misinterpreted some basic elements of optical theory.[22] For example, one of these misconceptions can be seen in the general belief that the Divisionist method of painting allowed for greater luminosity than previous techniques. Additive luminosity is only applicable in the case of colored light, not juxtaposed pigments; in reality, the luminosity of two pigments next to each other is just the average of their individual luminosities.[22] Furthermore, it is not possible to create a color using optical mixture that could not also be created by physical mixture. Logical inconsistencies can also be found with the Divisionist exclusion of darker colors and their interpretation of simultaneous contrast.[22]

Gallery

[edit]-

Georges Seurat, 1889–90, Le Chahut, Kröller-Müller Museum (detail)

-

Henri Matisse, 1899, Still Life with Compote, Apples and Oranges, Baltimore Museum of Art

-

Pablo Picasso, 1901, Old Woman (Woman with Gloves, Woman With Jewelry), Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

André Derain, 1905, Le séchage des voiles (The Drying Sails), Pushkin Museum

-

Robert Antoine Pinchon, 1905, La Seine à Rouen au crépuscule

-

Robert Delaunay, 1906, Paysage au disque, Musée National d'Art Moderne

-

Henri-Edmond Cross, 1906, La fuite des nymphes, Musée d'Orsay

-

Piet Mondrian, 1909, Dune III, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

-

Paul Signac, 1909, The Pine Tree at Saint Tropez, Pushkin Museum

-

Gino Severini, 1911, Souvenirs de Voyage (Memories of a Journey, Ricordi di viaggio), private collection

-

Hippolyte Petitjean, c.1912, Le Pont Neuf, Metropolitan Museum of Art

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Tosini, Aurora Scotti, "Divisionism", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online.

- ^ a b Homer, William I. Seurat and the Science of Painting. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1964.

- ^ a b Ratliff, Floyd. Paul Signac and Color in Neo-Impressionism. New York: Rockefeller UP, 1992. ISBN 0-87470-050-7.

- ^ a b "Divisionism: History, Painting Method of Georges Seurat". www.visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ a b "Color mixing". physics.bu.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "Additive and Subtractive Color Mixing". isle.hanover.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "Simultaneous and Successive Contrast". colorusage.arc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ "Divisionism | art | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ Tate. "Impressionism". Tate. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ Kemp, Martin (May 2008). "The Impressionists' bible". Nature. 453 (7191): 37. Bibcode:2008Natur.453...37K. doi:10.1038/453037a. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 34142687.

- ^ "Impressionism | Definition, History, Art, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-01-27.

- ^ a b c Sutter, Jean. The Neo Impressionists. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1970. ISBN 0-8212-0224-3.

- ^ a b c Smith, Paul. Seurat, Georges. Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online

- ^ a b Rapetti Rodolphe Signac, Paul Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online

- ^ Ruhrberg, Karl. "Seurat and the Neo-Impressionists". Art of the 20th Century, Vol. 2. Cologne: Taschen, 1998. ISBN 3-8228-4089-0.

- ^ Robert Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1968

- ^ Il Sole Nascente is found at the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome.

- ^ Arc Lamp is found in Museum of Modern Art, New York

- ^ The City Rises is also found in the MoMA

- ^ Derived from paragraph in Associazione Pellizza da Volpedo Archived November 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, which cites Enciclopedia dell'arte, Milano (Garzanti) 2002, and also see Voci del Divisionismo italiano in Bollettino Anisa, N. 12 Anno XIX, n. 1, May 2000.

- ^ a b Rewald, John. Seurat: a biography. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1990. ISBN 0-8109-3814-6.

- ^ a b c Lee, Alan. "Seurat and Science." Art History 10 (June 1987): 203-24.

Further reading

[edit]- Blanc, Charles. The Grammar of Painting and Engraving. Chicago: S.C. Griggs and Company, 1891. [1].

- Block, Jane. "Neo-Impressionism." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. [2].

- Block, Jane. "Pointillism." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. [3].

- Broude, Norma, ed. Seurat in Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1978. ISBN 0-13-807115-2.

- Cachin, Françoise. Paul Signac. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1971. ISBN 0-8212-0482-3.

- Clement, Russell T., and Annick Houzé. Neo-impressionist painters: a sourcebook on Georges Seurat, Camille Pissarro, Paul Signac, Théo van Rysselberghe, Henri Edmond Cross, Charles Angrand, Maximilien Luce, and Albert Dubois-Pillet. Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 1999. ISBN 0-313-30382-7.

- Chevreul, Michel Eugène. The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors. London: Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden, 1860

- Dorra, Henri. Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthology. Berkeley: U of California, 1994.

- Gage, John. "The Technique of Seurat: A Reappraisal." The Art Bulletin 69 (Sep. 1987): 448-54. JSTOR. The Technique of Seurat: A Reappraisal.

- Herbert, Robert. Georges Seurat, 1859-1891, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991. ISBN 9780870996184.

- Herbert, Robert L. Neo-Impressionism. New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1968.

- Hutton, John G. Neo-impressionism and the search for solid ground: art, science, and anarchism in fin-de-siècle France. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State UP, 1994. ISBN 0-8071-1823-0.

- Puppo, Dario del. "Il Quarto Stato." Science and Society, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 13, 1994.

- Meighan, Judith. "In Praise of Motherhood: The Promise and Failure of Painting for Social Reform in Late-Nineteenth-Century Italy." Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2002.

- "Radical Light: Italy's Divisionist Painters." History Today, August 2008.

- Rewald, John. Georges Seurat. New York: Wittenborn & Co., 1946.

- Roslak, Robyn. Neo-Impressionism and Anarchism in Fin-de-Siecle France: Painting, Politics and Landscape. N.p.: n.p., 2007.

- Signac, Paul. D’Eugène Delacroix au Neo-Impressionnisme. 1899. [4].

- Winkfield, Trevor. "The Signac Syndrome." Modern Painters Autumn 2001: 66-70.

- Tim Parks on divisionist movement of painters in Italy

.svg/250px-Color_star-en_(tertiary_names).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Color_star-en_(tertiary_names).svg.png)