Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

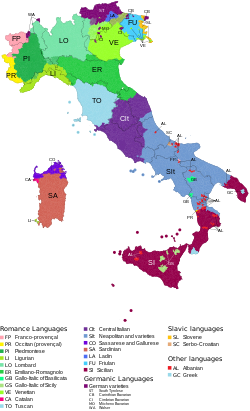

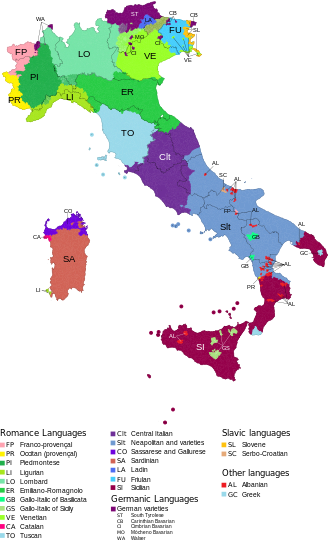

Languages of Italy

View on Wikipedia

This article may incorporate text from a large language model. (May 2025) |

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

The languages of Italy constitute one of the richest and most varied linguistic heritages within the European panorama[7]. In fact, only about 45.9% of the Italian population speak Italian at home.[8]

Italian serves as the country's national language, in its standard and regional forms, as well as numerous local and regional languages, most of which, like Italian, belong to the broader Romance group. The majority of languages often labelled as regional are distributed in a continuum across the regions' administrative boundaries, with speakers from one locale within a single region being typically aware of the features distinguishing their own variety from others spoken nearby.[9]

At the time of the political unification of most of Italy under the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1861, according to Tullio De Mauro, Italian speakers made up 2.5% of the population.[10]The language later spread widely among the general population through compulsory education, urbanization, internal migration, bureaucracy, military service, and mass media (both print and audiovisual media) starting from the 1950s.

The official and most widely spoken language across the country is Italian, which started off based on the medieval Tuscan of Florence. In parallel, many Italians also communicate in one of the local languages, most of which, like Tuscan, are indigenous evolutions of Vulgar Latin. Some local languages do not stem from Latin, however, but belong to other Indo-European branches, such as Cimbrian (Germanic), Arbëresh (Albanian), Slavomolisano (Slavic) and Griko (Greek). Other non-indigenous languages are spoken by a substantial percentage of the population due to immigration.

After Italian, the second most spoken language in Italy is another Italian-Romance variant of the same family as Italian: Neapolitan language, spoken by about 11 million people in certain central-southern regions of the country.[11]

Of the indigenous languages, twelve are officially recognized as spoken by linguistic minorities:[12] Albanian,[13][14] Catalan, German, Greek, Slovene, Croatian, French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Ladin, Occitan and Sardinian;[12] Sardinian is regarded as one of the largest of such groups, with approximately one million speakers, even though the Sardophone community is overall declining.[15][16][17] However, full bilingualism (bilinguismo perfetto) is legally granted only to the three national minorities whose mother tongue is German, Slovene or French, and enacted in the regions of Trentino-Alto Adige, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and the Aosta Valley, respectively.

Ancient languages of Italy

[edit]

Numerous languages were spoken in ancient Italy. These included Etruscan and the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages, consisting of Latino-Faliscan and Osco-Umbrian languages. Furthermore, Celtic languages were spoken in Cisalpine Gaul and ancient Greek was spoken in Magna Graecia. Latin emerged out of the Latino-Faliscan group and replaced the other languages spoken in Italy following the Romanization of the whole peninsula; it is the ancestor of all the Romance languages, the only living subgroup of the Italic languages.

Language or dialect

[edit]Almost all of the Romance languages spoken in Italy are native to the area in which they are spoken. Apart from Standard Italian, these languages are often referred to as dialetti "dialects", both colloquially and in scholarly usage; however, the term may coexist with other labels like "minority languages" or "vernaculars" for some of them.[18] The label "dialect" may be understood erroneously to imply that the native languages spoken in Italy are "dialects" of Standard Italian in the prevailing English-language sense of "varieties or variations of a language".[19][20] This is not the case in Italy, as the country's long-standing linguistic diversity does not actually stem from Standard Italian. Most of Italy's variety of Romance languages predate Italian and evolved locally from Vulgar Latin, independently of what would become the standard national language, long before the fairly recent spread of Standard Italian throughout Italy.[21][20] In fact, Standard Italian itself can be thought of as either a continuation of, or a language heavily based on, the Florentine dialect of Tuscan. Thus, the Romance languages of Italy that are commonly referred to as "dialects" are described as such in a sociolinguistic sense: they are languages that are socially subordinate to Standard Italian, which is the politically and culturally dominant language.

The indigenous Romance languages of Italy are therefore classified as separate languages that evolved from Latin just like Standard Italian, rather than "dialects" or variations of the latter.[22][23][24] Conversely, with the spread of Standard Italian throughout Italy in the 20th century, local varieties of Standard Italian have also developed throughout the peninsula, influenced to varying extents by the underlying local languages, most noticeably at the phonological level; though regional boundaries seldom correspond to isoglosses distinguishing these varieties, these variations of Standard Italian are commonly referred to as Regional Italian (italiano regionale).[20]

Twelve languages have been legally granted official recognition as of 1999, but their selection to the exclusion of others is a matter of some controversy.[19] Daniele Bonamore argues that many regional languages were not recognized in light of their communities' historical participation in the construction of the Standard Italian language: Giacomo da Lentini's and Cielo d'Alcamo's Sicilian, Guido Guinizelli's Bolognese, Jacopone da Todi's Umbrian, Neapolitan, Carlo Goldoni's Venetian and Dante's Tuscan are considered to be historical founders of the Standard Italian linguistic majority; outside of such epicenters are, on the other hand, Friulian, Ladin, Sardinian, Franco-Provençal and Occitan, which are recognized as distinct languages.[25] Michele Salazar found Bonamore's explanation "new and convincing".[26]

Legal status of Italian

[edit]Italian was first declared to be Italy's official language during the Fascist period, more specifically through the R.D.l., adopted on 15 October 1925, with the name of: "Sull'Obbligo della lingua italiana in tutti gli uffici giudiziari del Regno, salvo le eccezioni stabilite nei trattati internazionali per la città di Fiume."[27]

The first Italian Constitution of 1948 establishes Italian as the official national language. Article 1 of Law 482/1999 states: "La lingua ufficiale della Repubblica è l’italiano" ("The official language of the Republic is Italian"[28] Since the constitution was penned, some laws and articles have been written on the procedures of criminal cases passed that explicitly state that Italian should be used:

- Statute of the Trentino-South Tyrol (constitutional law of the northern region of Italy around Trento): "[...] [la lingua] italiana [...] è la lingua ufficiale dello Stato." (Statuto Speciale per il Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Art. 99, "[...] [the language] Italian [...] is the official language of the State.")

- Code for civil procedure: "In tutto il processo è prescritto l'uso della lingua italiana." (Codice di procedura civile, Art. 122, "In all procedures, the use of the Italian language is required.")

- Code for criminal procedure: "Gli atti del procedimento penale sono compiuti in lingua italiana." (Codice di procedura penale, Art. 109 [169-3; 63, 201 att.], "The acts of the criminal proceedings are carried out in the Italian language.")

Historical linguistic minorities

[edit]Recognition by the Italian state

[edit]

The Republic safeguards linguistic minorities by means of appropriate measures.

— Italian Constitution, Art. 6

Art. 6 of the Italian Constitution was drafted by the Founding Fathers to show sympathy for the country's historical linguistic minorities, in a way for the newly founded Republic to let them become part of the national fabric and distance itself from the Italianization policies promoted earlier because of nationalism.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the use of standard Italian became increasingly widespread and was mirrored by a decline in the use of the dialects. An increase in literacy was one of the main driving factors (one can assume that only literates were capable of learning standard Italian, whereas those who were illiterate had access only to their native dialect). The percentage of literates rose from 25% in 1861 to 60% in 1911, and then on to 78.1% in 1951. Tullio De Mauro, an Italian linguist, has asserted that in 1861, only 2.5% of the population of Italy could speak standard Italian. He reports that in 1951, that percentage had risen to 87%. The ability to speak Italian did not necessarily mean that it was in everyday use, and most people (63.5%) still usually spoke their native dialects.

During Fascism,[31][32][33] which even carried out a persecution of alloglots minorities[34] ,since especially from the 1930s onward, the regime began to view local varieties as a threat to the country’s cultural and linguistic unity and as a potential encouragement of autonomist claims. Yet, initially, the Fascist education reform enacted in 1923 by Giovanni Gentile, whose curricula were drafted by Giuseppe Lombardo Radice, set aside the prevailing anti-dialectal attitude in schools, aiming instead to combat illiteracy starting from the student’s linguistic background before moving on to the national language (according to the “from dialect to language” method)[35]. It was instead with the 1934 school programs (“Ercole programs”) that “dialects” once again came to be regarded solely as sources of errors to be sanctioned, as had been the case in the 1905 programs and as would be in those of 1955.[36]

For the Constitutional Court of the Italian Republic, Article 6 of the Constitution represents "the overcoming of the closed notion of the 19th-century national State and a reversal of great political and cultural significance, compared to the nationalistic attitude manifested by Fascism" as well as being "one of the fundamental principles of the current constitutional system".[37]

However, more than a half century passed before the Art. 6 was followed by any of the above-mentioned "appropriate measures".[38] Italy applied in fact the Article for the first time in 1999, by means of the national law N.482/99.[12] According to the linguist Tullio De Mauro, the Italian delay of over 50 years in implementing Article 6 was caused by "decades of hostility to multilingualism" and "opaque ignorance".[39]

Before said legal framework entered into force, only four linguistic minorities (the French-speaking community in the Aosta Valley; the German-speaking community and, to a limited extent, the Ladin one in the Province of Bolzano; the Slovene-speaking community in the Province of Trieste and, with less rights, the Province of Gorizia) enjoyed some kind of acknowledgment and protection, stemming from specific clauses within international treaties.[31] The other eight linguistic minorities were to be recognized only in 1999, including the Slovene-speaking minority in the Province of Udine and the Germanic populations (Walser, Mocheni and Cimbri) residing in provinces different from Bolzano. Some now-recognized minority groups, namely in Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Sardinia, already provided themselves with regional laws of their own. It has been estimated that less than 400.000 people, out of the two million people belonging to the twelve historical minorities (with Sardinian being the numerically biggest one[16][15][17]), enjoyed state-wide protection.[40]

Around the 1960s, the Italian Parliament eventually resolved to apply the previously neglected article of the country's fundamental Charter. The Parliament thus appointed a "Committee of three Sages" to single out the groups that were to be recognized as linguistic minorities, and further elaborate the reason for their inclusion. The nominated people were Tullio de Mauro, Giovan Battista Pellegrini and Alessandro Pizzorusso, three notable figures who distinguished themselves with their life-long activity of research in the field of both linguistics and legal theory. Based on linguistic, historical as well as anthropological considerations, the experts eventually selected thirteen groups, corresponding to the currently recognized twelve with the further addition of the Sinti and Romani-speaking populations.[41] The original list was approved, with the only exception of the nomadic peoples, who lacked the territoriality requisite and therefore needed a separate law. However, the draft was presented to the law-making bodies when the legislature was about to run its course, and had to be passed another time. The bill was met with resistance by all the subsequent legislatures, being reluctant to challenge the widely held myth of "Italian linguistic homogeneity",[38] and only in 1999 did it eventually pass, becoming a law. In the end, the historical linguistic minorities have been recognized by the Law no. 482/1999 (Legge 15 Dicembre 1999, n. 482, Art. 2, comma 1).[12][42]

Some interpretations of said law seem to divide the twelve minority languages into two groups, with the first including the non-Latin speaking populations (with the exception of the Catalan-speaking one) and the second including only the Romance-speaking populations. Some other interpretations state that a further distinction is implied, considering only some groups to be "national minorities".[38][43] Regardless of the ambiguous phrasing, all the twelve groups are technically supposed to be allowed the same measures of protection;[44] furthermore, the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, signed and ratified by Italy in 1997, applies to all the twelve groups mentioned by the 1999 national law, therefore including the Friulians, the Sardinians,[45][46][47] the Occitans, the Ladins etc., with the addition of the Romani.

In actual practice, not each of the twelve historical linguistic minorities is given the same consideration.[38] All of them still bear strong social pressure to assimilate to Italian, and some of them do not even have a widely acknowledged standard to be used for official purposes.[48] In fact, the discrimination lay in the urgent need to award the highest degree of protection only to the French-speaking minority in the Aosta Valley and the German one in South Tyrol, owing to international treaties.[49] For example, the institutional websites are only in Italian with a few exceptions, like a French version of the Italian Chamber of Deputies.[50] A bill proposed by former prime minister Mario Monti's cabinet formally introduced a differential treatment between the twelve historical linguistic minorities, distinguishing between those with a "foreign mother tongue" (the groups protected by agreements with Austria, France and Slovenia) and those with a "peculiar dialect" (all the others). The bill was later implemented, but deemed unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court.[51][52]

Recognition at the European level

[edit]Italy is a signatory of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, but has not ratified the treaty, and therefore its provisions protecting regional languages do not apply in the country.[53]

The Charter does not, however, establish at what point differences in expression result in a separate language, deeming it an "often controversial issue", and citing the necessity to take into account, other than purely linguistic criteria, also "psychological, sociological and political considerations".[54]

Regional recognition of the local languages

[edit]- Aosta Valley:

- French is co-official (enjoying the same dignity and standing of Italian) in the whole region (Le Statut spécial de la Vallée d'Aoste, Titre VIe, Article 38);[55]

- Franco-Provençal is unofficial, but protected and promoted according to state and regional laws.[55][56]

- German is unofficial but recognised in the Lys Valley (Lystal) (Le Statut spécial de la Vallée d'Aoste, Titre VIe, Art. 40 - bis).[55]

- Apulia:

- Basilicata:

- Calabria:

- Calabrian Greek, Arbëresh and Occitan are officially recognized and safeguarded.

- Campania: Neapolitan is "promoted", but not recognised, by the region (Reg. Gen. nn. 159/I 198/I, Art. 1, comma 4).[60]

- Friuli-Venezia Giulia:

- Lombardy:

- Piedmont:

- Piedmontese is unofficial but recognised as the regional language (Consiglio Regionale del Piemonte, Ordine del Giorno n. 1118, Presentato il 30 November 1999);[65][66]

- the region "promotes", without recognising, the Occitan, Franco-Provençal, French and Walser languages (Legge regionale 7 aprile 2009, n. 11, Art. 1).[67]

- Sardinia:

- The region considers the cultural identity of the Sardinian people as a primary asset (l.r. N.26/97,[68] l.r. N.22/18[69]), in accordance with the values of equality and linguistic pluralism enshrined in the Italian Constitution and the European treaties, with particular reference to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (l.r. N.26/97).[68] All the languages indigenous to the island (Sardinian, Catalan, Tabarchino, Sassarese and Gallurese) are recognised and promoted as "enjoying the same dignity and standing of Italian" (l.r. N.26/97)[68] in their respective linguistic areas.

- Sicily:

- Gallo-Italic of Sicily and Arbëresh are officially recognized and safeguarded.

- Sicilian is unofficial but recognised as the regional language (Legge regionale 9/2011).[70]

- South Tyrol:

- Trentino:

- Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol

- Veneto:

Conservation status

[edit]

According to the UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, there are 31 endangered languages in Italy.[78] The degree of endangerment is classified in different categories ranging from 'safe' (safe languages are not included in the atlas) to 'extinct' (when there are no speakers left).[79]

The source for the languages' distribution is the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger[78] unless otherwise stated, and refers to Italy exclusively.

Vulnerable

[edit]- Alemannic: spoken in the Lys Valley of the Aosta Valley and in Northern Piedmont

- Bavarian: South Tyrol

- Ladin: several valleys, comunes and villages in the Dolomites, including the Val Badia and the Gardena Valley in South Tyrol, the Fascia Valley in Trentino, and Livinallongo in the Province of Belluno

- Sicilian: Sicily, southern and central Calabria and southern Apulia

- Neapolitan: Campania, Basilicata, Abruzzo, Molise, northern Calabria, northern and central Apulia, southern Lazio and Marche as well as eastern fringes of Umbria

- Romanesco: Metropolitan City of Rome in Lazio and in some communes of southern Tuscany

- Venetian (Venetan): Veneto, parts of Friuli-Venezia Giulia

Definitely endangered

[edit]- Algherese Catalan: the town of Alghero in northwestern Sardinia; an outlying dialect of Catalan language not listed separately by the SIL International.

- Occitan Alpine Provençal: the upper valleys of Piedmont (Val Mairo, Val Varacho, Val d'Esturo, Entraigas, Limoun, Vinai, Pinerolo, Sestriere)

- Arbëresh: (i) Adriatic zone: Montecilfone, Campomarino, Portocannone and Ururi in Molise as well as Chieuti and Casalvecchio di Puglia in Apulia; (ii) San Marzano in Apulia; (iii) Greci in Campania; (iv) northern Basilicata: Barile, Ginestra and Maschito; (v) North Calabrian zone: ca. 30 settlements in northern Calabria (Plataci, Civita, Frascineto, San Demetrio Corone, Lungro, Acquaformosa etc.) as well as San Costantino Albanese and San Paolo Lucano in southern Basilicata; (vi) settlements in southern Calabria, e.g. San Nicola dell'Alto and Vena di Maida; (vii) Sicilian zone: Piana degli Albanesi and two nearby villages near Palermo; (viii) formerly also Villabadessa in Abruzzo; an outlying dialect of Albanian

- Cimbrian: vigorously spoken in Luserna in Trentino; disappearing in Giazza (part of the commune Selva di Progno) in the Province of Verona and in Roana in the Province of Vicenza; recently extinct in several other locations in the region; an outlying Bavarian dialect

- Corsican: spoken on Maddalena Island off the northeast coast of Sardinia

- Emilian: North to Northwestern Emilia-Romagna, parts of the provinces of Pavia, Voghera, and Mantua in southern Lombardy, the Lunigiana district in northwestern Tuscany and in a zone called Traspadana Ferrarese in the Province of Rovigo in Veneto

- Romagnol: Southeastern Emilia-Romagna, the Alta Valle del Tevere district in northern part of the Province of Perugia and eastern part of the Province of Arezzo, the Province of Pesaro-Urbino in the Marche (disputed)

- Faetar: Faeto and Celle San Vito in the Province of Foggia in Apulia; a variety of Franco-Provençal not listed separately by the SIL

- Franco-Provençal: spoken in the Aosta Valley (Valdôtain dialect) and the Alpine valleys to the north and east of the Susa Valley in Piedmont

- Friulan: Friuli-Venezia Giulia except the Province of Trieste and western and eastern border regions, and Portogruaro area in the Province of Venice in Veneto

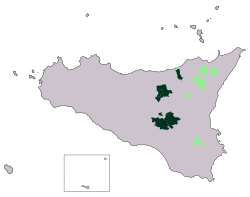

- Gallo-Italic of Sicily: Nicosia, Sperlinga, Piazza Armerina, Valguarnera Caropepe and Aidone in the province of Enna, and San Fratello, Acquedolci, San Piero Patti, Montalbano Elicona, Novara di Sicilia and Fondachelli-Fantina in the province of Messina; an outlying dialect of Lombard not listed separately by the SIL; other dialects were formerly also spoken in southern Italy outside Sicily, especially in Basilicata

- Gallurese: northeastern Sardinia; an outlying dialect of Corsican

- Ligurian: Liguria and adjacent areas of Piedmont, Emilia and Tuscany; settlements in the towns of Carloforte on the San Pietro Island and Calasetta on the Sant'Antioco Island off the southwest coast of Sardinia

- Lombard: Lombardy (except the southernmost border areas) and the Province of Novara in Piedmont

- Mòcheno: Palù, Fierozzo and Frassilongo in the Fersina Valley in Trentino; an outlying Bavarian dialect

- Piedmontese: Piedmont except the Province of Novara, the western Alpine valleys and southern border areas, as well as minor adjacent areas

- Resian: Resia in the northeastern part of the Province of Udine; an outlying dialect of Slovene not listed separately by the SIL

- Romani: spoken by the Roma community in Italy

- Sardinian, consisting of both the Campidanese (southern Sardinia) and Logudorese (central Sardinia) dialects

- Sassarese: northwestern Sardinia; a transitional language between Corsican and Sardinian

- Yiddish: spoken by parts of the Jewish community in Italy[80]

Severely endangered

[edit]- Walser German: the village of Issime in the upper Lys Valley/Lystal in the Aosta Valley; an outlying dialect of Alemannic not listed separately by the SIL. It is considered by Glottolog to be a separate language.

- Molise Croatian: the villages of Montemitro, San Felice del Molise, and Acquaviva Collecroce in the Province of Campobasso in southern Molise;[81] a mixed Chakavian–Shtokavian dialect of Croatian not listed separately by the SIL. It is considered by Glottolog to be a separate language.

- Griko: the Salento peninsula in the Province of Lecce in southern Apulia; an outlying dialect of Greek not listed separately by the SIL. It is considered by Glottolog to be a separate language known as Apulia-Calabrian Greek.

- Gardiol Occitan: Guardia Piemontese in Calabria; an outlying dialect of Occitan Alpine Provençal. It is considered by Glottolog to be a separate language.

- Griko (Calabria): a few villages near Reggio di Calabria in southern Calabria; an outlying dialect of Greek not listed separately by the SIL. It is considered by Glottolog to be a separate language known as Apulia-Calabrian Greek.

Classification

[edit]All living languages indigenous to Italy are part of the Indo-European language family.

They can be divided into Romance languages and non-Romance languages. The classification of the Romance languages of Italy is controversial, and listed here are two of the generally accepted classification systems.

Romance languages

[edit]Loporcaro [82] proposes a classification of Romance languages of Italy based on Pellegrini,[83] who groups different Romance languages according to areal and some typological features. The following five linguistic areas can be identified:[84]

- Northern (dialetti settentrionali):

- Gallo-Italic (Emilian,[85] Lombard, Piedmontese, Ligurian)

- Venetan (dialetti veneti)

- Friulian

- Tuscan

- Mid-Southern (dialetti centro-meridionali):

- Middle (dialetti mediani; Central Marchigiano, Umbrian, Laziale).

- Upper Southern (dialetti alto-meridionali; Marchigiano-Abruzzese, Molisano, Apulian, Southern Laziale and Campanian including Neapolitan, Northern Lucano-Calabrese).

- Extreme Southern (dialetti meridionali estremi; Salentino, Calabrian, Sicilian).

- Sardinian

The following classification is proposed by Maiden and Parry:[86]

- Northern varieties:

- Northern Italo-Romance:

- 'Gallo-Italian' (Piedmont, Lombardy, Liguria and Emilia-Romagna).

- Venetan.

- Ladin.

- Friulian.

- Northern Italo-Romance:

- Central and Southern:

- Tuscan (with Corsican).

- 'Middle Italian' (Marche, Umbria, Lazio).

- Upper Southern (Abruzzo, northern Puglia, Molise, Campania, Basilicata).

- Extreme Southern (Salento, southern Calabria and Sicily).

- Sardinian.

Non-Romance languages

[edit]Albanian, Slavic, Greek and Romani languages

[edit]| Language | Family | ISO 639-3 | Dialects spoken in Italy | Notes | Speakers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arbëresh | Albanian | Tosk | aae | According to Minority Rights Group International: "The ethnic Albanian (Arbëresh) dialects of Italy bear little resemblance to the standard language or dialects of Albania, as they have been cut off from the main language for around 500 years. Some dialects spoken in Italy are so dissimilar that ethnic Albanians use Italian as a lingua franca. Ethnic Albanians are bilingual."[87] | recognized as a variant of the Albanian strain by UNESCO[78] | 100,000 | ||

| Croatian | Slavic | South | Western | hr | Molise Croatian | 1,000 | ||

| Slovene (slovenščina) | Slavic | South | Western | slv | Gai Valley dialect; Resian; Torre Valley dialect; Natisone Valley dialect; Brda dialect; Karst dialect; Inner Carniolan dialect; Istrian dialect | 100,000 | ||

| Italiot Greek | Hellenic (Greek) | Attic | ell | Griko (Salento); Calabrian Greek | 20,000 | |||

| Romani | Indo-Iranian | Indo-Aryan | Central Zone | Romani | rom | By ISO 639-3 classification, Sinte Romani is the individual language most present in Italy in the Romany macrolanguage | ||

High German languages

[edit]| Language | Family | ISO 639-3 | Dialects spoken in Italy | Notes | Speakers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German | Middle German | East Middle German | deu | Tyrolean dialects | Austrian German is the usual standard variety | 315,000 |

| Cimbrian | Upper German | Bavarian-Austrian | cim | sometimes considered a dialect of Bavarian, also considered an outlying dialect of Bavarian by the UNESCO[78] | 2,200 | |

| Mocheno | Upper German | Bavarian-Austrian | mhn | considered an outlying dialect of Bavarian by the UNESCO[78] | 1,000 | |

| Walser | Upper German | Alemannic | wae | 3,400 | ||

Geographic distribution

[edit]Northern Italy

[edit]The Northern Italian languages are conventionally defined as those Romance languages spoken north of the La Spezia–Rimini Line, which runs through the northern Apennine Mountains just to the north of Tuscany; however, the dialects of Occitan and Franco-Provençal spoken in the extreme northwest of Italy (e.g. the Valdôtain in the Aosta Valley) are generally excluded. The classification of these languages is difficult and not agreed-upon, due both to the variations among the languages and to the fact that they share isoglosses of various sorts with both the Italo-Romance languages to the south and the Gallo-Romance languages to the northwest.

One common classification divides these languages into four groups:

- The Italian Rhaeto-Romance languages, including Ladin and Friulian.

- The poorly researched Istriot language.

- The Venetian language (sometimes grouped with the majority Gallo-Italian languages).

- The Gallo-Italian languages, including all the rest (although with some doubt regarding the position of Ligurian).

Any such classification runs into the basic problem that there is a dialect continuum throughout northern Italy, with a continuous transition of spoken dialects between e.g. Venetian and Ladin, or Venetian and Emilio-Romagnolo (usually considered Gallo-Italian).

All of these languages are considered innovative relative to the Romance languages as a whole, with some of the Gallo-Italian languages having phonological changes nearly as extreme as standard French (usually considered the most phonologically innovative of the Romance languages). This distinguishes them significantly from standard Italian, which is extremely conservative in its phonology (and notably conservative in its morphology).[88]

Southern Italy and islands

[edit]Approximate distribution of the regional languages of Sardinia and Southern Italy according to the UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger:

One common classification divides these languages into two groups:

- The Italo-Dalmatian languages, including Neapolitan and Sicilian, as well as the Sardinian-influenced Sassarese and Gallurese which are sometimes grouped with Sardinian but are actually of southern Corsican origin.

- The Sardinian language, usually listed as a group of its own with two main Logudorese and Campidanese orthographic forms.

All of these languages are considered conservative relative to the Romance languages as a whole, with Sardinian being the most conservative of them all.

Mother tongues of foreign citizens in Italy

[edit]| Language (2018)[89][90] | Population |

|---|---|

| Romanian | 806,938 |

| Albanian | 441,027 |

| Arabic | 420,980 |

| Chinese | 299,823 |

| Spanish | 285,664 |

| Ukrainian | 239,424 |

| Filipino | 168,292 |

| Italian | 162,148 |

| Others | 892,283 |

Standardised written forms

[edit]Although "[al]most all Italian dialects were being written in the Middle Ages, for administrative, religious, and often artistic purposes",[91] use of local language gave way to stylized Tuscan, eventually labeled Italian. Local languages are still occasionally written, but only the following regional languages of Italy have a standardised written form. This may be widely accepted or used alongside more traditional written forms:

- Piedmontese: traditional, definitely codified between the 1920s and the 1960s by Pinin Pacòt and Camillo Brero

- Ligurian: "Grafîa ofiçiâ" created by the Académia Ligùstica do Brénno;[92]

- Sardinian: "Limba Sarda Comuna" was experimentally adopted in 2006;[93]

- Friulian: "Grafie uficiâl" created by the Osservatori Regjonâl de Lenghe e de Culture Furlanis;[94]

- Ladin: "Grafia Ladina" created by the Istituto Ladin de la Dolomites;[95]

- Venetian: "Grafia Veneta Unitaria", the official manual published in 1995 by the Regione Veneto local government, although written in Italian.[96] It has been recently updated on 14 December 2017, under the name of "Grafia Veneta Ufficiale".[97]

Gallery

[edit]-

Officially recognised ethno-linguistic minorities of Italy

-

Regional languages of Italy according to Clemente Merlo and Carlo Tagliavini in 1939

-

Languages and language islands of Italy

-

Languages of Italy

-

Main dialectal groups of Italy

-

Main linguistic groups of Italy

-

Percentage of people in Italy having a command of a regional language (Doxa, 1982; Coveri's data, 1984)

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Tagliavini, Carlo (1962). Le origini delle lingue neolatine: introduzione alla filologia romanza. R. Patròn. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- ^ "La variazione diatopica". Archived from the original on 16 February 2012.

- ^ [1] Archived 7 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ AIS, Sprach-und Sachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz, Zofingen 1928-1940

- ^ "Cittadini Stranieri in Italia - 2025".

- ^ "Italian National Institute of Statistics:Lingua italiana, dialetti e altre lingue".

- ^ Maiden Parry,1997,p.1:"Italy holds especial treasures for linguists. There is probably no other area of Europe in which such a profusion of linguistic variation is concentrated into so small a geographical area"

- ^ "Uso della lingua italiana, dei dialetti e delle lingue straniere – Anno 2015" (PDF) (in Italian). Istituto nazionale di statistica (ISTAT). 27 December 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- ^ "Italy". Ethnologue. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ De Mauro, Tullio (1976) [1960]. "Una lingua d'elezione". Storia linguistica dell'Italia unita (in Italian). Vol. I (4th ed.). Bari: Editori Laterza. p. 43.

- ^ "Patrimoni linguistici: Cosa si intende per lingua napoletana".

- ^ a b c d Norme in materia di tutela delle minoranze linguistiche storiche, Italian parliament, retrieved 17 October 2015: "1. In attuazione dell'articolo 6 della Costituzione e in armonia con i princípi generali stabiliti dagli organismi europei e internazionali, la Repubblica tutela la lingua e la cultura delle popolazioni albanesi, catalane, germaniche, greche, slovene e croate e di quelle parlanti il francese, il franco-provenzale, il friulano, il ladino, l'occitano e il sardo."

- ^ Curtis, Matthew C. (2018). "99. The dialectology of Albanian". In Fritz, Matthias; Joseph, Brian; Klein, Jared (eds.). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. de Gruyter Mouton. p. 1800. ISBN 9783110542431.

The Albanian language is spoken natively by approximately 6 million speakers in south-eastern Europe, particularly in Albania and Kosovo where it is an official language, but also in Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, and Italy where it has the status of a minority language.

- ^ "Albanians in Italy". Minority Rights Group International.

- ^ a b "Letture e linguaggio. Indagine Multiscopo sulle famiglie "I cittadini e il tempo libero"" (PDF). ISTAT. 2000. pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b "Lingue di Minoranza e Scuola, Sardo". Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ a b "What Languages are Spoken in Italy?". 29 July 2019.

- ^ Loporcaro 2009; Marcato 2007; Posner 1996; Repetti 2000:1–2; Cravens 2014.

- ^ a b Cravens 2014

- ^ a b c Domenico Cerrato. "Che lingua parla un italiano?". Treccani.it. Archived from the original on 11 February 2018.

- ^ Tullio, de Mauro (2014). Storia linguistica dell'Italia repubblicana: dal 1946 ai nostri giorni. Editori Laterza, ISBN 9788858113622

- ^ Maiden, Martin; Parry, Mair (7 March 2006). The Dialects of Italy. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 9781134834365.

- ^ Repetti 2000, p. 1.

- ^ Andreose, Alvise; Renzi, Lorenzo (2013), "Geography and distribution of the Romance Languages in Europe", in Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (eds.), The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages, vol. 2, Contexts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 302–308

- ^ Bonamore, Daniele (2006). Lingue minoritarie Lingue nazionali Lingue ufficiali nella legge 482/1999, Editore Franco Angeli, p.16

- ^ Michele Salazar (Università di Messina, Direttore Rivista giuridica della scuola) - Presentazione: (…) La spiegazione datane nell'opera sotto analisi appare nuova e convincente (…) il siciliano (…) il bolognese (…) l'umbro (…) il toscano (…) hanno fatto l'italiano, sono l'italiano - Bonamore, Daniele (2008). Lingue minoritarie Lingue nazionali Lingue ufficiali nella legge 482/1999, Editore Franco Angeli

- ^ Caretti, Paolo; Rosini, Monica; Louvin, Roberto (2017). Regioni a statuto speciale e tutela della lingua. Turin, Italy: G. Giappichelli. p. 72. ISBN 978-88-921-6380-5.

- ^ "Legge 482". Webcitation.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Sergio Lubello (2016). Manuale Di Linguistica Italiana. Manuals of Romance linguistics. De Gruyter. p. 506.

- ^ "Lingue di Minoranza e Scuola: Carta Generale". Minoranze-linguistiche-scuola.it. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Tutela delle minoranze linguistiche e articolo 6 Costituzione".

- ^ "Articolo 6 Costituzione, Dispositivo e Spiegazione".

- ^ Paolo Coluzzi (2007). Minority Language Planning and Micronationalism in Italy: An Analysis of the Situation of Friulian, Cimbrian and Western Lombard with Reference to Spanish Minority Languages. Peter Lang. p. 97.

- ^ Alberto Raffaelli, Lingua del fascismo, Treccani.it, Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 2010. URL consultato il 25 ottobre 2025.

- ^ Francesco Avolio, Tra lingua e dialetto, in Lingue e dialetti d’Italia, Roma, Carocci, 2009, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Silvia Demartini (2010). Dal dialetto alla lingua negli anni Venti del Novecento. Pisa-Roma, Fabrizio Serra Editore; p.78

- ^ Sentenze Corte costituzionale n. 15 del 1996, n. 62 del 1992, n. 768 del 1988, n. 289 del 1987 e n. 312 del 1983. Dalla sentenza nr. 15 del 1996 : 2.- «La tutela delle minoranze linguistiche è uno dei principi fondamentali del vigente ordinamento che la Costituzione stabilisce all'art. 6, demandando alla Repubblica il compito di darne attuazione "con apposite norme". Tale principio, che rappresenta un superamento delle concezioni dello Stato nazionale chiuso dell'Ottocento e un rovesciamento di grande portata politica e culturale, rispetto all'atteggiamento nazionalistico manifestato dal fascismo, è stato numerose volte valorizzato dalla giurisprudenza di questa Corte, anche perché esso si situa al punto di incontro con altri principi, talora definiti "supremi", che qualificano indefettibilmente e necessariamente l'ordinamento vigente (sentenze nn. 62 del 1992, 768 del 1988, 289 del 1987 e 312 del 1983): il principio pluralistico riconosciuto dall'art. 2 - essendo la lingua un elemento di identità individuale e collettiva di importanza basilare - e il principio di eguaglianza riconosciuto dall'art. 3 della Costituzione, il quale, nel primo comma, stabilisce la pari dignità sociale e l'eguaglianza di fronte alla legge di tutti i cittadini, senza distinzione di lingua e, nel secondo comma, prescrive l'adozione di norme che valgano anche positivamente per rimuovere le situazioni di fatto da cui possano derivare conseguenze discriminatorie.»

- ^ a b c d "Schiavi Fachin, Silvana. Articolo 6, Lingue da tutelare". 15 June 2017.

- ^ Tratto dalla “Presentazione” a firma del prof. Tullio De Mauro della prima edizione (31 dicembre 2004) del Grande Dizionario Bilingue Italiano-Friulano – Regione autonoma Friuli-Venezia Giulia – edizione CFL2000, Udine, pag. 5/6/7/8: «Anzitutto occorre rievocare il vasto movimento mondiale che ha segnato la fine dell'ideologia monolinguistica e delle politiche culturali, scolastiche, legislative a essa ispirata. (…) I grandi Stati nazionali europei si sono andati costituendo, a partire dal secolo XV, sull'assioma di una vincolante identità tra Stato-nazione-lingua. (…) Il divergente esempio svizzero a lungo è stato percepito come una curiosità isolata.(…) Le vie percorso dal plurilinguismo (…). In Italia il percorso, come si sa, non è stato agevole.(…) Nella pluridecennale ostilità ha operato un difetto profondo di cultura, un'opaca ignoranza fatta dall'intreccio di molte cose. (…) Finalmente nel 1999, vinte resistenze residue, anche lo Stato italiano si è dotato di una legge che, non eccelsa, attua tuttavia quanto disponeva l'art. 6 della Costituzione (...)»

- ^ Salvi, Sergio (1975). Le lingue tagliate. Storia della minoranze linguistiche in Italia, Rizzoli Editore, pp. 12–14

- ^ Camera dei deputati, Servizio Studi, Documentazione per le Commissioni Parlamentari, Proposte di legge della VII Legislatura e dibattito dottrinario,123/II, marzo 1982

- ^ "Italy's general legislation, Language Laws". Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ [2] Archived 16 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bonamore, Daniele (2008). Lingue minoritarie lingue nazionali lingue ufficiali nella legge 482/1999, FrancoAngeli Editore, Milano, p. 29

- ^ "Lingua Sarda, Legislazione Internazionale, Sardegna Cultura".

- ^ "Coordinamentu sardu ufitziale, lettera a Consiglio d'Europa: "Rispettare impegni"". 17 April 2017.

- ^ "Il Consiglio d'Europa: "Lingua sarda discriminata, norme non-rispettate"". 24 June 2016.

- ^ Gabriele Iannàccaro (2010). "Lingue di minoranza e scuola. A dieci anni dalla Legge 482/99. Il plurilinguismo scolastico nelle comunità di minoranza della Repubblica Italiana" (PDF). p. 82. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ See the appeal of the attorney Felice Besostri against the Italian electoral law of 2015.

- ^ "Chambre des députés".

- ^ "Sentenza Corte costituzionale nr. 215 del 3 luglio 2013, depositata il 18 luglio 2013 su ricorso della regione Friuli-VG".

- ^ "Anche per la Consulta i friulani non-sono una minoranza di serie B" (PDF).

- ^ "Chart of signatures and ratifications of Treaty 148". Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ What is a regional or minority language?, Council of Europe, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ a b c Statut spécial de la Vallée d'Aoste, Title VIe, Region Vallée d'Aoste, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ "Conseil de la Vallée - Loi régionale 1er août 2005, n. 18 - Texte en vigueur". Retrieved 25 April 2020

- ^ Puglia, QUIregione - Il Sito web Istituzionale della Regione. "QUIregione - Il Sito web Istituzionale della Regione Puglia". QUIregione - Il Sito web Istituzionale della Regione Puglia. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ Balduzzi, Erica (25 May 2020). "Una lingua, un'identità: alla scoperta del griko salentino". Itinerari e Luoghi (in Italian). Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ "Promozione e salvaguardia delle minoranze linguistiche". Regione Basilicata.

- ^ Reg. Gen. nn. 159/I 198/I, Norme per lo Studio, la Tutela, la Valorizzazione della Lingua. Napoletana, dei Dialetti e delle Tradizioni Popolari in. Campania (PDF), Consiglio Regionale della Campania, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Norme per la tutela, valorizzazione e promozione della lingua friulana, Regione Autonoma Friuli-Venezia Giulia, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Norme regionali per la tutela della minoranza linguistica slovena, Regione Autonoma Friuli-Venezia Giulia, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Norme di tutela e promozione delle minoranze di lingua tedesca del Friuli Venezia Giulia, Regione Autonoma Friuli-Venezia Giulia, retrieved 24 July 2024

- ^ "L.R. 25/2016 - 1. Ai fini della presente legge, la Regione promuove la rivitalizzazione, la valorizzazione e la diffusione di tutte le varietà locali della lingua lombarda, in quanto significative espressioni del patrimonio culturale immateriale, attraverso: a) lo svolgimento di attività e incontri finalizzati a diffonderne la conoscenza e l'uso; b) la creazione artistica; c) la diffusione di libri e pubblicazioni, l'organizzazione di specifiche sezioni nelle biblioteche pubbliche di enti locali o di interesse locale; d) programmi editoriali e radiotelevisivi; e) indagini e ricerche sui toponimi. 2. La Regione valorizza e promuove tutte le forme di espressione artistica del patrimonio storico linguistico quali il teatro tradizionale e moderno in lingua lombarda, la musica popolare lombarda, il teatro di marionette e burattini, la poesia, la prosa letteraria e il cinema. 3. La Regione promuove, anche in collaborazione con le università della Lombardia, gli istituti di ricerca, gli enti del sistema regionale e altri qualificati soggetti culturali pubblici e privati, la ricerca scientifica sul patrimonio linguistico storico della Lombardia, incentivando in particolare: a) tutte le attività necessarie a favorire la diffusione della lingua lombarda nella comunicazione contemporanea, anche attraverso l'inserimento di neologismi lessicali, l'armonizzazione e la codifica di un sistema di trascrizione; b) l'attività di archiviazione e digitalizzazione; c) la realizzazione, anche mediante concorsi e borse di studio, di opere e testi letterari, tecnici e scientifici, nonché la traduzione di testi in lingua lombarda e la loro diffusione in formato digitale."

- ^ Ordine del Giorno n. 1118, Presentato il 30/11/1999, Consiglio Regionale del Piemonte, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Ordine del Giorno n. 1118, Presentato il 30/11/1999 (PDF), Gioventura Piemontèisa, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Legge regionale 7 aprile 2009, n. 11. (Testo coordinato) "Valorizzazione e promozione della conoscenza del patrimonio linguistico e culturale del Piemonte", Consilio Regionale del Piemonte, retrieved 2 December 2017

- ^ a b c "Legge Regionale 15 ottobre 1997, n. 26". Regione autonoma della Sardegna – Regione Autònoma de Sardigna.

- ^ "Legge Regionale 3 Luglio 2018, n. 22". Regione autonoma della Sardegna – Regione Autònoma de Sardigna.

- ^ "Gazzetta Ufficiale della Regione Siciliana - Anno 65° - Numero 24" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ a b Statuto speciale per il Trentino-Alto Adige (PDF), Regione.taa.it, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2018, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ "Autonomy One region, three languages: German, Italian and Ladin". home.provinz.bz.it (in German). 12 June 2025. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Languages in South Tyrol - true diversity".

- ^ "62013Cj0322".

- ^ Sonderstatut für Trentino-Südtirol, Article 99, Title IX. Region Trentino-Südtirol.

- ^ Legge regionale 13 aprile 2007, n. 8, Consiglio Regionale del Veneto, archived from the original on 25 March 2013, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ ISTAT Report "Use of Italian language, dialects, and foreign languages" (English version), ISTAT, 2017, retrieved 18 November 2020 ; "L'uso della lingua italiana, dei dialetti e di altre lingue in Italia (Italian version)". ISTAT. 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, UNESCO's Endangered Languages Programme, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Degrees of endangerment, UNESCO's Endangered Languages Programme, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ "La straordinaria rinascita dello Yiddish. Chi lo studia, chi lo parla e chi si nutre delle sue radici (anche italiane)" (in Italian). 4 July 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "Endangered languages in Europe: report". Helsinki.fi. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Loporcaro 2009:70

- ^ Pellegrini 1977

- ^ Note that Loporcaro uses the term dialetto 'dialect' throughout the book, intended as 'non-national language'. Since dialect has a different connotation in English, we avoid it here.

- ^ Hajek (1997:273) separates Emilian and Romagnol, with Bolognese characterized as transitional between the two.

- ^ Maiden & Parry 1997:3

- ^ "Albanians in Italy". Minority Rights Group International.

- ^ Hull, Geoffrey, PhD thesis 1982 (University of Sydney), published as The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language. 2 vols. Sydney: Beta Crucis, 2017.

- ^ "Linguistic diversity among foreign citizens in Italy". Statistics of Italy. 25 July 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Stranieri residenti e condizioni di vita : Lingua madre". Istat.it. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ Andreose, Alvise; Renzi, Lorenzo (2013), "Geography and distribution of the Romance Languages in Europe", in Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (eds.), The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages, vol. 2, Contexts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 303

- ^ Grafîa ofiçiâ, Académia Ligùstica do Brénno, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Limba sarda comuna, Sardegna Cultura, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ Grafie dal O.L.F., Friûl.net, retrieved 17 October 2015

- ^ PUBLICAZIOIGN DEL ISTITUTO LADIN, Istituto Ladin de la Dolomites, retrieved 17 October 2015[permanent dead link]

- ^ Grafia Veneta Unitaria - Manuale a cura della giunta regionale del Veneto, Commissione regionale per la grafia veneta unitaria, archived from the original on 16 March 2016, retrieved 6 December 2016

- ^ "Grafia Veneta ufficiale – Lingua Veneta The modern international manual of the Venetian spelling". Lingua Veneta. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cravens, Thomas D. (2014). "Italia Linguistica and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages". Forum Italicum. 48 (2): 202–218. doi:10.1177/0014585814529221. S2CID 145721889.

- Hajek, John (1997), "Emilia-Romagna", in Maiden, Martin; Parry, Mair (eds.), The Dialects of Italy, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 271–278

- Loporcaro, Michele (2009). Profilo linguistico dei dialetti italiani (in Italian). Bari: Laterza.

- Maiden, Martin; Parry, Mair (1997). The Dialects of Italy. London and New York: Routledge.

- Marcato, Carla (2007). Dialetto, dialetti e italiano (in Italian). Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Posner, Rebecca (1996). The Romance languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pellegrini, Giovan Battista (1977). Carta dei dialetti d'Italia (in Italian). Pisa: Pacini.

- Repetti, Lori, ed. (2000). Phonological Theory and the Dialects of Italy. Amsterdam Studies in the Theory and History of Linguistic Science, Series IV Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Vol. 212. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

External links

[edit]- "LEGGE 15 dicembre 1999, n. 482 - Normattiva". www.normattiva.it.

- NavigAIS Archived 11 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Online version of the Sprach- und Sachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz (AIS) (Linguistic and Ethnographic Atlas of Italy and Southern Switzerland)

- An interactive map of languages and dialects in Italy

- Ethnologue - Languages of Italy

- Rivista Etnie, linguistica

Languages of Italy

View on GrokipediaHistorical Origins and Evolution

Pre-Roman Indigenous Languages

Prior to the rise of Roman hegemony in the 4th to 1st centuries BC, the Italian peninsula hosted a linguistic mosaic of indigenous languages spoken by diverse peoples during the Iron Age (c. 1000–500 BC). These included non-Indo-European languages such as Etruscan, alongside Indo-European branches like the Italic languages and Venetic. Evidence derives primarily from inscriptions, with Etruscan yielding over 13,000 texts, mostly short funerary or votive, dating from the 7th century BC to the 1st century BC.[10] Etruscan, the tongue of the Etruscans in central Italy (encompassing modern Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio), stands as the best-attested non-Indo-European language of pre-Roman Italy. Classified within the Tyrsenian family, potentially linking it to Raetic in the Alps and Lemnian on the Aegean island of Lemnos, Etruscan featured an agglutinative structure with no known close relatives among major language families. Its alphabet, adapted from Euboean Greek around 700 BC, influenced early Latin script, yet the language resisted decipherment beyond basic vocabulary and grammar due to limited bilingual texts.[11] Indo-European languages predominated among indigenous groups, with the Italic branch encompassing Osco-Umbrian (Sabellic) dialects in central and southern Italy and Latino-Faliscan in Latium. Oscan, spoken by Samnites, Lucanians, and others from Campania to Apulia, was the most widespread Italic variety before Latin's expansion, attested in over 600 inscriptions from the 5th century BC onward, using a script derived from Etruscan or Greek. Umbrian, from the region north of Rome, survives in texts like the Iguvine Tables (c. 300–100 BC), revealing ritual and legal usage. Latino-Faliscan included early Latin in Latium and the closely related Faliscan near Veii, with Latin inscriptions emerging around 600 BC. These languages shared phonological traits like initial stress and case systems but diverged in vocabulary and morphology.[12][10] Other Indo-European languages included Venetic in the northeast (Veneto region), attested from the 6th century BC in about 300 inscriptions, characterized by unique vocabulary possibly influenced by Illyrian or Celtic elements. In the northwest, Ligurian may represent a pre-Indo-European substrate or an early Celtic dialect, with scant evidence from toponyms and glosses. Celtic languages arrived with Gallic migrations around 400 BC in the Po Valley, but indigenous pre-Celtic tongues like Lepontic (related to Gaulish) predate them slightly. Southern extremities featured Messapic, an Indo-European language akin to Albanian or Illyrian, spoken by Iapygians in Apulia and Calabria, known from 500 inscriptions dating to the 6th–1st centuries BC.[11][12] These languages coexisted with minimal mutual intelligibility, reflecting ethnic fragmentation, until Roman conquests from the 4th century BC onward imposed Latin, leading to their gradual extinction by the 1st century AD through assimilation, lack of literary tradition, and political subjugation. Oscan persisted longest in remote areas like Pompeii until the 79 AD eruption, while Etruscan influenced Latin loanwords in religion and governance.[10][12]Latin Dominance and Vulgar Latin Divergence

The expansion of the Roman Republic from the 4th century BC onward, through wars against neighboring Italic peoples and Etruscans, progressively imposed Latin as the administrative and military lingua franca across the Italian peninsula.[13] By 272 BC, Rome controlled the south, and after the Social War of 91–88 BC, the granting of citizenship to defeated allies accelerated linguistic unification, with Latin colonists resettling conquered territories like Pompeii and supplanting local languages such as Oscan and Umbrian within two to three generations.[10] Archaeological evidence from bilingual inscriptions confirms this rapid shift, as indigenous scripts and vocabularies faded under Latin's prestige in law, trade, and governance. By the 1st century AD, Latin dominated Italy entirely, with over 130,000 surviving inscriptions attesting to its ubiquity in public and private life, while pre-Roman substrates left traces in loanwords like lupus (from Oscan) for wolf.[10] Classical Latin, the refined literary standard codified by authors like Cicero in the late Republic, served elite and official purposes but diverged from Vulgar Latin, the everyday spoken form used by soldiers, merchants, slaves, and rural populations.[14] Vulgar Latin featured phonetic simplifications (e.g., loss of final consonants), grammatical streamlining (e.g., reduced case endings), and regional accents influenced by substrates, as noted in imperial-era complaints about "provincial" speech by figures like Hadrian.[10] Evidence from Pompeian graffiti, curse tablets, and non-standard papyri reveals these colloquial traits, including analytic structures prefiguring Romance syntax, distinct from Classical's synthetic complexity. Adoption was pragmatic rather than coercive: locals shifted to Latin for economic mobility and integration into Roman networks, with no empire-wide language edicts but incentives via citizenship and administration.[14][15] Post-3rd century AD, as the Empire centralized then fragmented, Vulgar Latin's regional dialects emerged more sharply in Italy due to geographic barriers like the Apennines and uneven urbanization. Northern varieties absorbed Celtic and later Germanic elements from invasions, central forms retained closer ties to urban Latin cores, and southern ones incorporated Greek and Oscan remnants, fostering a dialect continuum by the 5th century.[16] The Western Empire's collapse in 476 AD, followed by Ostrogothic and Lombard settlements, disrupted unifying infrastructure, allowing phonological drifts (e.g., vowel changes) and lexical innovations to solidify into proto-Italo-Romance branches without centralized standardization. This divergence, rooted in spoken variability rather than written norms, produced the Gallo-Italic, Tuscan, and Extremeño-Sicilian groups by the early medieval period, as attested in 8th–9th century placenames and oaths.[16]Medieval Fragmentation into Romance Varieties

Following the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, Vulgar Latin spoken across the Italian peninsula underwent accelerated regional differentiation, as the breakdown of centralized administration severed long-distance communication networks and fostered localized speech patterns insulated by natural barriers like the Apennine Mountains and Alpine ranges.[17][18] Political disintegration into competing entities—such as Ostrogothic, Byzantine, and later Frankish territories—reduced the unifying influence of imperial Latin, allowing substrate effects from pre-Roman Italic languages (e.g., Oscan in the south, Etruscan in central regions) to resurface variably in phonology and vocabulary.[19] The Lombard invasion of 568 CE, led by King Alboin, intensified this fragmentation by establishing a network of autonomous duchies across northern and central Italy, which curtailed population movements and embedded Germanic superstrate elements—estimated at under 2% of core lexicon but notable in terms like gard (enclosure, influencing northern terms for hedges)—primarily in Gallo-Italic varieties.[20] Despite initial bilingualism, Lombards shifted to Romance substrates by the 8th century under Frankish pressure, preserving Vulgar Latin's core while regional innovations proliferated: northern dialects adopted lenition patterns akin to Western Romance shifts, central forms retained more conservative vowels, and southern ones incorporated Greek loans from Byzantine holdouts.[21] Earliest textual attestation of this divergence appears in the Placiti Cassinesi, four legal acts from 960–963 CE adjudicating monastic land disputes near Capua, featuring vernacular phrases like sao ko kelle terre per karo meie spuso Kalende mai ("I know those lands which were pledged to me until the Calends of May"), diverging from Latin in case loss, verb forms, and syntax.[22][1] These documents, alongside the 8th-century Veronese Riddle, signal the crystallization of proto-Italo-Romance as distinct from ecclesiastical Latin, with phonological splits (e.g., northern palatalization of /k/ before /i/ yielding ci vs. southern chi) reflecting centuries of isolated evolution by the High Middle Ages.[23] This process yielded a dialect continuum rather than discrete languages, driven causally by feudal isolation over imperial koine enforcement, setting the stage for later standardization efforts.[24]Standard Italian: Foundation and Role

Tuscan Dialect as Basis for Standardization

The Tuscan dialect, particularly its Florentine variant, emerged as the basis for standard Italian primarily due to its literary prestige established in the 14th century. Dante Alighieri's Divina Commedia, composed between 1308 and 1321, marked the first major vernacular epic, using the everyday speech of Florence to achieve poetic sophistication that rivaled Latin.[25] This work, alongside Francesco Petrarch's Canzoniere (c. 1374) and Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron (1353), positioned Tuscan as a model for expressive prose and verse, surpassing other Italo-Romance varieties in cultural influence.[26][27] Florence's status as a Renaissance hub for banking, trade, and early printing amplified this dissemination, with Tuscan texts printed and circulated across Europe by the late 15th century, embedding its lexicon and syntax in educated discourse.[26][19] Tuscan's phonetic and morphological proximity to Vulgar Latin further recommended it for standardization, as its features—such as conservative vowel systems and minimal consonant shifts—facilitated intelligibility for Latin-literate scholars and clergy, unlike more divergent northern or southern dialects.[26] By the 16th century, grammarians like Pietro Bembo explicitly endorsed the Tuscan of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio as the exemplar for a unified literary language in his Prose della volgar lingua (1525), influencing subsequent codification efforts.[28] This prestige persisted despite regional fragmentation, as Tuscan-derived forms dominated printed literature, diplomacy, and theater through the 18th century. During Italy's unification in 1861 under the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont, the Savoy court initially favored its own Gallo-Italic dialect, but Tuscan's entrenched literary authority prevailed.[26] Alessandro Manzoni reinforced this in the 1820s by revising his novel I Promessi Sposi (originally 1827, revised 1840) to align with contemporary Florentine speech, arguing in essays like Dell'unità della lingua that a spoken, living standard—rooted in Tuscany—would foster national cohesion over artificial constructs.[28] Post-1861 educational reforms and mandatory schooling in the 19th century institutionalized Tuscan-based Italian, with Florence serving as capital from 1865 to 1871, accelerating its adoption despite only about 2.5% of the population speaking it natively at unification.[26] This choice reflected causal priorities of cultural continuity and prestige over political expediency, enabling standardization without wholesale imposition of a ruling dialect.Unification and Official Adoption

Upon the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy on March 17, 1861, the Tuscan dialect—elevated through its literary tradition exemplified by works of Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca, and Giovanni Boccaccio—served as the foundation for the standardized national language, adopted for administrative, legal, and educational purposes to promote unity across a fragmented linguistic landscape.[6] This choice reflected the prestige of Florentine Tuscan, further championed by Alessandro Manzoni's 1840 revision of I Promessi Sposi, which modeled a purified, spoken form accessible to the masses rather than archaic literary variants.[1] However, linguistic proficiency was minimal; linguist Tullio De Mauro estimated that only 2.5% of the population could speak standard Italian at unification, with the vast majority relying on regional Italo-Romance varieties or non-Romance minority languages for daily communication.[29] Standardization efforts intensified through state policies emphasizing education as a vehicle for linguistic assimilation. The Casati Law of November 13, 1859—initially enacted in the Kingdom of Sardinia but extended nationwide post-unification—established compulsory primary schooling conducted exclusively in Italian, aiming to eradicate illiteracy (which stood at approximately 78% in 1861) and instill the national tongue among dialect speakers.[1] Subsequent reforms, including the Coppino Law of 1877, expanded mandatory education to age nine and reinforced Italian's dominance in curricula, though implementation faced resistance in rural areas where dialects prevailed and teachers often lacked fluency. By 1901, literacy rates had risen to 56%, correlating with increased Italian usage, yet regional varieties persisted as primary vernaculars for over 80% of the populace into the early 20th century.[29] The transition to explicit official adoption occurred under the Fascist regime, which on October 15, 1925, enacted Royal Decree-Law 2116 declaring Italian the sole official language of the state, prohibiting dialects in public administration, schools, and media to consolidate national identity and suppress perceived regional separatism.[30] This policy accelerated diffusion, with radio broadcasts and propaganda in standard Italian reaching broader audiences; by 1951, De Mauro reported 91.7% comprehension levels, though active proficiency lagged. The 1948 Republican Constitution did not formally designate an official language, relying on de facto precedence, but Law 38 of May 3, 2007, affirmed Italian's role by promoting its teaching abroad while implicitly solidifying domestic status amid protections for recognized minorities under Law 482 of 1999.[31] These measures reflected causal pressures from modernization—industrialization, urbanization, and mass media—driving convergence toward standard Italian, independent of ideological impositions.[29]Contemporary Promotion and Global Influence

In contemporary Italy, standard Italian remains the mandatory language of public education from primary through secondary levels, serving as the medium of instruction for all core subjects and fostering national linguistic unity amid regional dialectal diversity.[32] Public media outlets, including the state broadcaster RAI, reinforce its prevalence through standardized programming that reaches urban and rural audiences alike, a legacy of post-World War II initiatives that accelerated the shift from dialects to standard forms among older generations.[33] Recent policies, such as the July 2024 law enhancing Italian proficiency requirements for immigrant students in primary and secondary schools, further prioritize its acquisition to support integration and academic equity.[34] Globally, standard Italian is spoken by an estimated 85 million people, encompassing roughly 64 million native speakers primarily in Italy and adjacent regions like Switzerland's Ticino and San Marino, alongside second-language users in diaspora communities across Argentina, the United States, Brazil, and Australia.[35] It ranks as the fourth most studied foreign language worldwide, attracting over 2 million learners annually—drawn by Italy's exports in opera, cinema, fashion, and cuisine—as evidenced by enrollment data from language institutes and universities in 115 countries.[36] This influence stems from historical emigration waves between 1880 and 1970, which established vibrant Italophone enclaves, and contemporary cultural diplomacy that ties linguistic competence to economic ties in tourism and heritage industries. Central to these efforts is the Società Dante Alighieri, founded in 1889 to safeguard and propagate Italian amid unification challenges; today, it operates over 400 committees across 80 countries, delivering online and in-person courses, PLIDA proficiency certifications (recognized for Italian citizenship and university admissions), and events that engaged 134,000 members as of recent reports.[37] [38] Complementing this, Italy maintains 83 Cultural Institutes abroad under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which coordinate language instruction, literary workshops, and multimedia programs to embed standard Italian in host nations' curricula and cultural exchanges.[39] These institutions collectively amplify Italian's soft power, with empirical tracking showing sustained growth in certified learners amid global interest in Romance languages for professional and migratory purposes.Regional Italo-Romance Varieties

Linguistic Classification and Mutual Intelligibility

The regional Italo-Romance varieties of Italy constitute the Italo-Dalmatian branch of the Romance languages, which evolved from Vulgar Latin spoken in the Italian peninsula following the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[40] This branch excludes Sardinian, classified as a separate primary lineage within Romance due to its distinct phonological and morphological developments, such as the preservation of Latin final vowels.[41] Italo-Dalmatian varieties are further subdivided into northern, central, southern, and extreme southern subgroups based on shared innovations in phonology, morphology, and syntax. The northern subgroup encompasses Gallo-Italic languages (including Lombard, Piedmontese, Emilian-Romagnol, and Ligurian) and the Venetian group, characterized by features like post-tonic vowel harmony and Gallo-Romance substrate influences.[42] Central varieties include Tuscan (the foundation of standard Italian) and transitional dialects such as Umbrian and Marchigiano, marked by intermediate vowel systems and conservative consonant retention. Southern Italo-Dalmatian comprises Neapolitan and related Campanian-Abruzzese forms, while the extreme southern group features Sicilian and Calabro, distinguished by outcomes like Latin /kt/ to /itt/ (e.g., lacte > latte in Italian but jatti in Sicilian).[43] Mutual intelligibility among Italo-Dalmatian varieties varies significantly, forming a dialect continuum where adjacent lects exhibit high comprehension but distant ones show substantial asymmetry and breakdown. Empirical assessments indicate lexical similarity between standard Italian and peripheral varieties like Piedmontese or Sicilian at approximately 80-85%, yet spoken intelligibility drops below 70% for non-adjacent pairs, falling short of the threshold often used to delineate distinct languages from dialects.[44] For instance, speakers of northern Gallo-Italic lects comprehend central Tuscan-derived Italian more readily than southern or extreme southern varieties, due to phonological divergences such as vowel reduction patterns and intervocalic voicing in the south. Comprehension is often unidirectional: dialect speakers, exposed to standard Italian through education and media since the 19th-century unification, understand it at rates exceeding 90%, whereas standard speakers struggle with unfamiliar dialects, achieving only 40-60% in controlled tests without context.[45] Historical records from medieval Italy corroborate this fragmentation, with chroniclers noting comprehension barriers between northern and southern vernaculars, necessitating Latin or ad hoc intermediaries for communication across regions.[45] Standard Italian thus functions as a koiné, enabling national cohesion despite underlying linguistic discontinuities that persist in rural and intergenerational use.Dialect Continuum vs. Distinct Languages Debate

The Italo-Romance varieties spoken across Italy exhibit characteristics of a dialect continuum, wherein adjacent local varieties demonstrate high degrees of mutual intelligibility due to gradual phonetic, lexical, and grammatical shifts, while intelligibility diminishes sharply over greater distances.[40] This continuum persisted from the medieval period onward, shaped by limited mobility and regional isolation until the 19th-century unification, but major isogloss bundles—such as the La Spezia–Rimini line separating Gallo-Italic northern varieties from Tuscan-influenced central ones—demarcate broader dialect groups with reduced comprehension between them.[46] For instance, speakers of Venetian or Lombard in the north may understand neighboring Emilian or Romagnol dialects but struggle with central or southern varieties like Neapolitan or Sicilian, where shared vocabulary drops below 70% and syntactic structures diverge significantly.[16] Linguists argue that these regional varieties qualify as distinct languages rather than mere dialects of standard Italian, based on structural autonomy and low inter-group mutual intelligibility, which parallels distinctions among other Romance languages like Occitan or Friulian.[47] Standard Italian, derived from 14th-century Tuscan and codified in the 16th century through works by Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, emerged as a literary norm post-1861 unification, but the varieties predate it and evolved separately from Vulgar Latin substrates, retaining unique innovations such as plural clitics in southern forms or definite article placement in northern ones. Empirical studies, including lexical distance metrics and comprehension tests, confirm asymmetry: northern Gallo-Italic speakers often comprehend Tuscan-based Italian at 80-90% but southern Extreme Italo-Dalmatian varieties at under 40%, underscoring phylogenetic branching rather than a unified subdialectal spectrum.[48] [16] The counterview, prevalent in Italian sociolinguistic policy and education, classifies them as dialects subordinate to Italian, emphasizing political unity and the role of standard Italian as a lingua franca imposed through schooling since 1871, when only 2.5% of the population spoke it fluently per the 1861 census.[46] This perspective prioritizes sociopolitical criteria over purely linguistic ones, as articulated by Max Weinreich's dictum that "a language is a dialect with an army and navy," reflecting how state standardization marginalized pre-existing vernaculars without erasing their independent developmental trajectories.[47] Critics, including dialectologists like Tullio De Mauro, highlight that such labeling perpetuates diglossia, where Italian dominates formal domains while vernaculars persist informally, yet recognition as languages could foster preservation amid declining transmission rates—down to 32% daily use in 2015 surveys.[49] Despite this, international classifications like Ethnologue treat major varieties (e.g., Sicilian, Neapolitan) as separate languages, aligning with glottochronological divergence estimates of 1,000-1,500 years from common Vulgar Latin roots.[16]Geographic Distribution in Northern, Central, and Southern Italy

In Northern Italy, encompassing regions such as Piedmont, Lombardy, Liguria, and Emilia-Romagna, the predominant Italo-Romance varieties belong to the Gallo-Italic subgroup, characterized by phonological and lexical influences from Gallo-Romance substrates. Piedmontese is primarily spoken in Piedmont, Lombard in Lombardy (with Western, Eastern, and Alpine subvarieties), Ligurian along the Riviera in Liguria, and Emilian-Romagnol across Emilia-Romagna, reflecting a dialect continuum with gradual variations.[42][50] Veneto hosts Venetian, often classified separately due to its distinct phonological features like post-tonic vowels, while Trentino-Alto Adige features Trentino dialects akin to Venetian and Ladin varieties in alpine valleys, influenced by Rhaeto-Romance.[50] These northern varieties exhibit limited mutual intelligibility with standard Italian and southern forms, separated by the La Spezia–Rimini line, a major isogloss marking the transition from Gallo-Italic to central-southern Italo-Dalmatian traits.[42] Central Italy, including Tuscany, Umbria, Marche, and northern Lazio, is dominated by Central Italian dialects within the Italo-Dalmatian branch, showing closer alignment to standard Italian derived from Tuscan. Tuscan varieties prevail in Tuscany, with Florentine serving as the historical basis for standardization due to its preservation of Latin vowel systems and phonetic clarity.[51] Umbrian dialects occupy Umbria, Marchigiano spans Marche with northern and central subvarieties, and Romanesco extends into parts of Lazio around Rome, featuring innovations like metaphony and article reduction.[2][50] These dialects form a transitional zone, bridging northern Gallo-Italic influences in the north with southern innovations southward, though retaining high mutual intelligibility with standard Italian compared to peripheral regions.[51] Southern Italy, comprising Campania, Abruzzo, Molise, Puglia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily, hosts Upper and Extreme Southern Italo-Romance varieties, distinguished by conservative Latin retentions and Greek or Arabic substrate effects. Neapolitan and Campanian dialects are widespread in Campania and southern Lazio/Abruzzo, while Northern Lucano-Calabrese covers Basilicata and northern Calabria, and Apulian (including Barese) in Puglia's Adriatic coast.[52] Extreme Southern forms include Sicilian across Sicily with Gallo-Italic enclaves from medieval migrations, South Calabrian in southern Calabria, and Salentino in Apulia's Salento peninsula, marked by features like voiceless stops for Latin /b d g/ and distinct vowel systems.[53][2] This distribution underscores a north-south cline in linguistic divergence, with southern varieties often exhibiting greater lexical diversity from historical Norman, Aragonese, and Byzantine contacts.[52]Non-Romance Indigenous and Historical Minorities

Germanic and High German Varieties