Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Peterhouse, Cambridge

View on Wikipedia

Peterhouse is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Peterhouse has around 300 undergraduate and 175 graduate students, and 54 fellows.[4]

Key Information

Peterhouse alumni are notably eminent within the natural sciences, including scientists Lord Kelvin, Henry Cavendish, Charles Babbage, James Clerk Maxwell, James Dewar, Frank Whittle, and five Nobel prize winners in science: Sir John Kendrew, Sir Aaron Klug, Archer Martin, Max Perutz, and Michael Levitt.[5] Peterhouse alumni also include Lord Chancellors, Lord Chief Justices, important poets such as Thomas Gray, the first Anglican Bishop of New York Samuel Provoost, the first British Fields Medallist Klaus Roth, Oscar-winning film director Sam Mendes and comedian David Mitchell. British Prime Minister Augustus FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton, and Elijah Mudenda, second prime minister of Zambia, also studied at the college.

Peterhouse is one of the wealthiest colleges in Cambridge,[6] with assets exceeding £350 million.[7] It is currently third in terms of net assets per student. Members of Peterhouse are encouraged to attend communal dinners, known as "Hall". Hall takes place in two sittings, with the second known as "Formal Hall", which consists of a three-course candlelit meal and which must be attended wearing suits and gowns. At Formal Hall, the students rise as the fellows proceed in, a gong is rung, and two Latin graces are read. Peterhouse also hosts a biennial white-tie ball as part of May Week celebrations.

In recent years, Peterhouse has been ranked as one of the highest achieving colleges in Cambridge, although academic performance tends to vary year to year due to its small population. In the past five years, it has sat in the top ten of the 29 colleges within the Tompkins Table.[when?] Peterhouse sat at fourth in 2018 and 2019.

History

[edit]

Foundation

[edit]The foundation of Peterhouse dates to 1280, when letters patent from Edward I dated Burgh, Suffolk, 24 December 1280 allowed Hugh de Balsham, to keep a number of scholars in the Hospital of St John,[8] where they were to live according to the rules of the scholars of Merton.[9] After disagreement between the scholars and the Brethren of the Hospital, both requested a separation.[10] As a result, in 1284 Balsham transferred the scholars to the present site with the purchase of two houses just outside the then Trumpington Gate to accommodate a Master and fourteen "worthy but impoverished Fellows". The Church of St Peter without Trumpington Gate was to be used by the scholars.[10] Bishop Hugo de Balsham died in 1286, bequeathing 300 marks that were used to buy further land to the south of St Peter's Church, on which the college's Hall was built.

The earliest surviving set of statutes for the college was given to it by the then Bishop of Ely, Simon Montacute, in 1344. Although based on those of Merton College, these statutes clearly display the lack of resources then available to the college. They were used in 1345 to defeat an attempt by Edward III to appoint a candidate of his own as scholar. In 1354–55, William Moschett set up a trust that resulted in nearly 70 acres (280,000 m2) of land at Fen Ditton being transferred to the College by 1391–92. The College's relative poverty was relieved in 1401 when it acquired the advowson and rectory of Hinton through the efforts of Bishop John Fordham and John Newton. During the reign of Elizabeth I, the college also acquired the area formerly known as Volney's Croft, which today is the area of St Peter's Terrace, the William Stone Building and the Scholars' Garden.

16th century onwards

[edit]In 1553, Andrew Perne was appointed Master. His religious views were pragmatic enough to be favoured by both Mary I, who gave him the Deanery of Ely, and Elizabeth I. A contemporary joke was that the letters on the weathervane of St Peter's Church could represent "Andrew Perne, Papist" or "Andrew Perne, Protestant" according to which way the wind was blowing.[10] Having previously been close to the reformist Regius Chair of Divinity, Martin Bucer, later as vice-chancellor of the university Perne would have Bucer's bones exhumed and burnt in Market Square. John Foxe in his Actes and Monuments singled this out as "shameful railing". There is a hole burnt in the middle of the relevant page in Perne's own copy of Foxe.[11] Perne died in 1589, leaving a legacy to the college that funded a number of fellowships and scholarships, as well bequeathing an extensive collection of books. This collection and rare volumes since added to it is now known as the Perne Library.

Between 1626 and 1634, the Master was Matthew Wren. Wren had previously accompanied Charles I on his journey to Spain to attempt to negotiate the Spanish Match. Wren was a firm supporter of Archbishop William Laud, and under Wren the college became known as a centre of Arminianism. This continued under the Mastership of John Cosin, who succeeded Wren in 1634. Under Cosin significant changes were made to the college's Chapel to bring it into line with Laud's idea of the "beauty of holiness".[10] On 13 March 1643, in the early stages of the English Civil War, Cosin was expelled from his position by a Parliamentary ordinance from the Earl of Manchester. The Earl stated that he was deposed "for his opposing the proceedings of Parliament, and other scandalous acts in the University".[12] On 21 December of the same year, statues and decorations in the Chapel were pulled down by a committee led by the Puritan zealot William Dowsing.[10][13]

The college was the first in the University to have electric lighting installed, when Lord Kelvin provided it for the Hall and Combination Room to celebrate the College's six-hundredth anniversary in 1883–1884. It was the second building in the country to get electric lighting, after the Palace of Westminster.[5]

The college developed a strong reputation for the teaching of history from the time of Harold Temperley,[14] and during World War II its fellowship simultaneously included four professors in the university's faculty for that subject – Herbert Butterfield, David Knowles, Michael Postan and Denis Brogan.[15]

Modern day

[edit]In the 1980s Peterhouse acquired an association with Conservative politics. Maurice Cowling and Roger Scruton were both influential fellows of the College and are sometimes described as key figures in the so-called "Peterhouse right" – an intellectual movement linked to philosophical conservativism.[16] While often associated with Thatcherite politics (notably, the Conservative politicians Michael Portillo and Michael Howard both studied at Peterhouse), the extent to which Margaret Thatcher's economic liberalism was admired within the movement was limited. During this period, which coincided with the mastership of Hugh Trevor-Roper, the college endured a period of significant conflict among the fellowship, particularly between Trevor-Roper and Cowling.[17]

Trevor-Roper feuded constantly with Cowling and his allies, while launching a series of administrative reforms. Women were admitted in 1983 at his urging. The British journalist Neal Ascherson summarised the quarrel between Cowling and Trevor-Roper as:

Lord Dacre, far from being a romantic Tory ultra, turned out to be an anti-clerical Whig with a preference for free speech over superstition. He did not find it normal that fellows should wear mourning on the anniversary of General Franco's death, attend parties in SS uniform or insult black and Jewish guests at high table. For the next seven years, Trevor-Roper battled to suppress the insurgency of the Cowling clique ("a strong mind trapped in its own glutinous frustrations"), and to bring the college back to a condition in which students might actually want to go there. Neither side won this struggle, which soon became a campaign to drive Trevor-Roper out of the college by grotesque rudeness and insubordination.[18]

In a review of Adam Sisman's 2010 biography of Trevor-Roper, the Economist wrote that picture of Peterhouse in the 1980s was "startling", stating the college had become under Cowling's influence a sort of right-wing "lunatic asylum", who were determined to sabotage Trevor-Roper's reforms.[19] In 1987 Trevor-Roper retired complaining of "seven wasted years."[20]

Peterhouse may have been one of the sources of inspiration for Tom Sharpe's Porterhouse Blue.[21]

Buildings and grounds

[edit]

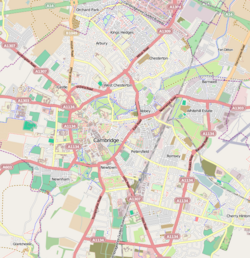

Peterhouse has its main site situated on Trumpington Street, to the south of Cambridge's town centre. The main portion of the college is just to the north of the Fitzwilliam Museum, and its grounds run behind the museum. The buildings date from a wide variety of times, and have been much altered over the years. The college is reputed to have been at least partially destroyed by fire in 1420. The entrance of the college has shifted through its lifetime as well, with the change being principally the result of the demolition of the row of houses that originally lined Trumpington Street on the east side of the college. In 1574, a map shows the entrance being on the south side of a single main court. The modern entrance is to the east, straight onto Trumpington Street.[8]

First Court

[edit]The area closest to Trumpington Street is referred to as First Court. It is bounded to the north by the Burrough's Building (added in the 18th century), to the east by the street, to the south by the Porters' lodge and to the west by the chapel. Above the Porters' lodge is the Perne Library, named in honour of Andrew Perne, a former Master, and originally built in 1590 to house the collection that he donated to the college. It was extended towards the road in 1633 and features interior woodwork that was added in 1641–48 by William Ashley, who was also responsible for similar woodwork in the chapel.[22] Electric lighting was added to the library in 1937.[23] The area above the Perne Library was used as the Ward Library (the college's general purpose library) from 1952 to 1984, but that has now been moved to its own building in the north-west corner of the college site.[24]

Burrough's Building

[edit]The Burrough's Building is situated at the front of the college, parallel to the Chapel. It is named after its architect, Sir James Burrough, the Master of Caius,[25] and was built in 1736. It is one of several Cambridge neo-Palladian buildings designed by Burrough. Others include the remodelling of the Hall and Old Court at Trinity Hall and the chapel at Clare College. The building is occupied by fellows and college offices.

Old Court

[edit]

Old Court lies beyond the Chapel cloisters. To the south of the court is the dining hall, the only College building that survives from the 13th century and the oldest collegiate building in all of Cambridge. Between 1866 and 1870, the hall was restored by the architect George Gilbert Scott, Jr. Under Scott, the timber roof was repaired and two old parlours merged to form a new Combination Room. The stained glass windows were also replaced with Pre-Raphaelite pieces by William Morris, Ford Madox Brown and Edward Burne-Jones.[10] The fireplace (originally built in 1618) was restored with tiles by Morris, including depictions of St Peter and Hugo de Balsham.[26] The hall was extensively renovated in 2006-7.[citation needed]

The north and west sides of Old Court were added in the 15th century, and classicised in the 18th century.[10] The chapel makes up the fourth, east side to the court. Rooms in Old Court are occupied by a mixture of fellows and undergraduates. The north side of the court also house Peterhouse's MCR (Middle Combination Room).[citation needed]

Chapel

[edit]

Viewed from the main entrance to Peterhouse on Trumpington Street, the altar end of the Chapel is the most immediately visible building. The Chapel was built in 1628 when the Master of the time Matthew Wren (Christopher Wren's uncle) demolished the college's original hostels. Previously the college had employed the adjacent Church of St Mary the Less as its chapel. The Chapel was consecrated on 17 March 1632 by Francis White, Bishop of Ely.[8] The building's style reflects the contemporary religious trend towards Arminianism. The Laudian Gothic style of the Chapel mixes Renaissance details but incorporated them into a traditional Gothic building. The Chapel's Renaissance architecture contains a Pietà altarpiece and a striking ceiling of golden suns. Its placement in the centre of one side of a court, between open colonnades is unusual, being copied for a single other college (Emmanuel) by Christopher Wren.[27] The original stained glass was destroyed by Parliamentarians in 1643, with only the east window's crucifixion scene (based on Rubens's Le Coup de Lance) surviving.[nb 1] The current side windows are by Max Ainmiller, and were added in 1855. The cloisters on each side of the Chapel date from the 17th century. Their design was classicised in 1709, while an ornamental porch was removed in 1755.

The Peterhouse Partbooks, music manuscripts from the early years of the Chapel, survive, and are one of the most important collections of Tudor and Jacobean church music. The Choir of Peterhouse has recently attracted wider interest for its regular performances of this material, some of which has not been heard since the 16th century, and have released a CD of music from the Caroline partbooks.[29] The Organ in the Chapel was installed in 1765 John Snetzler. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Organ was expanded and renovated by Hill & Son (1893-94) and Noel Mander (1963). In 2023, the Organ underwent a substantial restoration and renovation project by Flentrop and Klais. This restoration uniquely provides two mechanical-action consoles: one 'historic' console intended to recreate the experience of playing Snetzler's original instrument; the other a contemporary console, to allow for the performance of a wider range of repertoire.[30]

The first person buried in the Chapel was Samuel Horne, a fellow of the college.[8] Horne was probably chaplain.

Gisborne Court

[edit]Gisborne Court is accessible through an archway leading from the west side of Old Court. It was built in 1825-6.[10] Its cost was met with part of a benefaction of 1817 from the Rev. Francis Gisborne, a former fellow. The court is built in white brick with stone dressings in a simple Gothic revival style from the designs of William McIntosh Brookes. Only three sides to the court were built, with the fourth side being a screen wall. The wall was demolished in 1939, leaving only its footing.[31] Rooms in Gisborne Court are mainly occupied by undergraduates. Many previously housed distinguished alumni, including Lord Kelvin in I staircase.

The Whittle Building, named after Petrean Frank Whittle, opened on the western side of Gisborne Court in early 2015. Designed in neo-gothic style by John Simpson Architects, it contains en-suite undergraduate accommodation, the student bar and common room, a function room and a gym. Its design recalls that of the original screen-wall that once stood in its place.[32] In 2015 the building was shortlisted for the Carbuncle Cup, given annually by the magazine Building Design to "the ugliest building in the United Kingdom completed in the last 12 months".[33][34]

Fen Court

[edit]Beyond Gisborne Court is Fen Court, a 20th-century building partially on stilts. Fen Court was built between 1939 and 1941 from designs by H. C. Hughes and his partner Peter Bicknell.[35] It was amongst the earliest buildings in Cambridge designed in the style of the Modern Movement pioneered by Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus. The carved panel by Anthony Foster over the entrance doorway evokes the mood in Britain as the building was completed. It bears the inscription DE PROFUNDIS CLAMAVI MCMXL — "out of the depths have I cried out 1940". These are the first words of Psalm 130, one of the Penitential Psalms. Alongside the inscription is a depiction of St Peter being saved from the sea.

An adjacent bath-house, known as the Birdwood Building, used to make up the western side of Gisborne Court. This was also designed by Hughes and Bicknell, and was built between 1932 and 1934.[35] It was demolished in 2013 to make way for the new Whittle Building.

Ward Library

[edit]

The north-west corner of the main site is occupied by former Victorian warehouses containing the Ward Library, as well as a theatre and function room. The building it is housed in was originally the University's Museum of Classical Archaeology and was designed by Basil Champneys in 1883. It was adapted to its modern purpose by Robert Potter in 1982 and opened in its current form as a library two years later. In recent years, the final gallery of the old museum building has been converted into a reading room, named the Gunn Gallery, after Chan Gunn.[36]

Gardens

[edit]

While officially being named the Grove, the grounds to the south of Gisborne Court have been known as the Deer Park since deer were brought there in the 19th century. During that period it achieved fame as the smallest deer park in England. After the First World War the deer sickened and passed their illness onto stock that had been imported from the Duke of Portland's estate at Welbeck Abbey in an attempt to improve the situation. There are no longer any deer.

The remainder of the college's gardens divide into areas known as the Fellows' Garden, just to the south of Old Court, and the Scholars' Garden, at the south end of the site, surrounding the William Stone Building.

William Stone Building

[edit]The William Stone Building stands in the Scholars' Garden and was funded by a £100,000 bequest from William Stone (1857–1958), a former scholar of the college. Erected in 1963-4, to a design by Sir Leslie Martin and Sir Colin St John Wilson, it is an eight-storey brick tower[37] housing eight fellows and 24 undergraduates. It has been refurbished, converting the rooms to en-suite.

Trumpington Street

[edit]The college also occupies a number of buildings on Trumpington Street.[38]

The Master's Lodge is situated across Trumpington Street from the College, and was bequeathed to the College in 1727 by a fellow, Charles Beaumont, son of the 30th Master of the college, Joseph Beaumont. It is built in red brick in the Queen Anne style.[5]

The Hostel is situated next to the Master's Lodge. It was built in a neo-Georgian style in 1926 from designs by Thomas Henry Lyon. The Hostel was intended to be part of a larger complex but only one wing was built. It currently houses undergraduates and some fellows. During World War II the London School of Economics was housed in The Hostel and nearby buildings, at the invitation of the Master and Fellows.[39]

Behind the Hostel lies Cosin Court, which provides accommodation for fellows and mature, postgraduate, and married students. The court is named for John Cosin (1594–1672) who was successively Master of Peterhouse, Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University and Prince-Bishop of Durham.

St Peter's Terrace is a row of Georgian townhouses houses first-year undergraduates, fellows, and some graduate students in basement flats. It is directly in front of the William Stone Building.[40]

Arms

[edit]The College has, during its history, used five different coats of arms. The one currently in use has two legitimate blazons. The first form is the original grant by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms, in 1575:

- Or four pallets Gules within a border of the last charged with eight ducal coronets of the first.

The College did, however, habitually use a version with three pallets, and this was allowed at the Herald's Visitation of Cambridgeshire in 1684. The latter version (with three pallets) was officially adopted by the Governing Body in 1935. The construction of the arms is that of the founder, Hugo de Balsham, surrounded by the crowns of the See of Ely.[41]

Grace

[edit]| Latin | English |

|---|---|

Benedic nos Domine, et dona Tua, quae de Tua largitate sumus sumpturi, et concede, ut illis salubriter nutriti, Tibi debitum obsequium praestare valeamus, per Christum Dominum nostrum, Amen. Deus est caritas, et qui manet in caritate in Deo manet, et Deus in eo: sit Deus in nobis, et nos maneamus in ipso. Amen. |

Bless us, O Lord, and Thy gifts, which of Thy bounty we are about to receive, and grant that, fed wholesomely upon them, we may be able to offer due service unto Thee, through Christ our Lord, Amen.

God is love; and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him: let God be in us, and let us remain in the same. Amen. |

Peterhouse and Jesus College are the only two colleges to have two separate halves to their grace, the first being a standard grace, and the second a quotation of 1 John 4:16.

People associated with Peterhouse

[edit]Members of Peterhouse — as masters, fellows (including honorary fellows) or students — are known as Petreans.[42]

-

John Whitgift

Archbishop of Canterbury -

The Duke of Grafton

Prime Minister of Great Britain -

Edward Law, 1st Baron Ellenborough

Lord Chief Justice -

Syed Mohammad Hadi

Sportsman -

Herbert Butterfield

Historian, philosopher, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge -

James Mason

Actor -

Niall Ferguson

Historian -

Michael Portillo

broadcaster and former politician -

Roger Scruton

Philosopher -

Sam Mendes Film and stage director, producer and screenwriter

Nobel laureates

[edit]Peterhouse has five Nobel laureates associated with it, either as former students or fellows.

- John Kendrew – Chemistry (1962) for determining the first atomic structures of proteins using X-ray crystallography.

- Sir Aaron Klug – Chemistry (1982) for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy.

- Michael Levitt – Chemistry (2013) for the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems.

- Archer Martin – Chemistry (1952) for his invention of partition chromatography.

- Max Perutz – Chemistry (1962) for determining the first atomic structures of proteins using X-ray crystallography.

Gallery

[edit]-

Chapel and main entrance

-

Part of St Peter's College, view from the private gardens, 1815

-

St Peter's College, Chapel, 1815

-

Peterhouse May Boat Crew, 1896

-

Peterhouse Deer Park in Spring

-

St Peter's Terrace

-

William Stone Building, Scholars' Garden

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "We went to Peter-house, 1643, December 21, with officers and soldiers, and in the presence of Mr. Hanscott, Mr. Wilson, the President Mr. Francis, Mr. Maxey, and other Fellows... We pulled down two mighty great angells, with wings, and divers other angells, and the 4 Evangelists, and Peter, with his keies on the chappell door and about a hundred chirubims and angells, and divers superstitious letters in gold."[28]

References

[edit]- ^ "Statutes of Peterhouse in the University of Cambridge" (PDF).

- ^ University of Cambridge (6 March 2019). "Notice by the Editor". Cambridge University Reporter. 149 (Special No 5): 1. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ "Peterhouse - for the year ended 30 June 2022" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Fellows by Seniority". Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ a b c "About the College". Peterhouse Website. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "Oxford and Cambridge university colleges hold £21bn in riches". TheGuardian.com. 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Annual Report and Accounts 2023" (PDF). Peterhouse College, Cambridge. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d Cooper, Charles Henry (1860). Memorials of Cambridge. Cambridge: William Metcalfe.

- ^ "'The colleges and halls: Peterhouse', A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3: The City and University of Cambridge (1959), pp. 334–340". Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walker, Thomas Alfred (1935). Peterhouse. Cambridge: W. Heffer and Sons Ltd.

- ^ Patrick Collinson, ‘Perne, Andrew (1519?–1589)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004).

- ^ Walker, John (1863). Robert Whittaker (ed.). The sufferings of the clergy of the Church of England during the great rebellion. London. p. 169. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Richard Crashaw". The Living Age. 157: 198. 28 April 1883. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ Soffer, Reba N. (2009). History, Historians, and Conservatism in Britain and America: From the Great War to Thatcher and Reagan. Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-19920-811-1.

- ^ Latham, A. J. H. (2007). "W. A. Cole". In Lyons, John S.; Cain, Louis P.; Williamson, Samuel H. (eds.). Reflections on the Cliometrics Revolution: Conversations with Economic Historians. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-13599-360-3.

- ^ "Peterhouse blues". The Guardian. 10 September 1999. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Maurice Cowling Obituary". The Times. London. 26 August 2005. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ Ascherson, Neal (19 August 2010). "The Liquidator". London Review of Books. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Not so ropey". The Economist. 22 July 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Sisman, Adam (2011). An Honourable Englishman: The Life of Hugh Trevor-Roper. Random House. p. 562. ISBN 9780679604730.

- ^ Sharpe, Tom (1 January 2002). [Porterhouse Blue]. Arrow Books/Random House.

- ^ "Peterhouse, Cambridge". Britain Express. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "The Perne Library". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Over the Perne Library". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "James Burrough". Cambridge 2000. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "Hall Chimneypiece". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Old Court, Looking East". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ Cooper, Trevor (26 April 2001). The Journal of William Dowsing: Iconoclasm in East Anglia during the English Civil War. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0851158334.

- ^ "Music from the Peterhouse Partbooks (Choir of Pete.. - 8.574700 | Discover more releases from Naxos". www.naxos.com. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ "The Organ | Peterhouse". www.pet.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "Gisborne Court". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Whittle Building". John Simpson Architects. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Watson, Anna (22 July 2010). "Six in race for Carbuncle Cup". bdonline.co.uk. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ "Carbuncle Cup: Whittle Building, Peterhouse, University of Cambridge". BD Online. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ a b Peterhouse Annual Record 2002/2003

- ^ "History of Peterhouse Libraries". Peterhouse Website. Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "William Stone Building". Peterhouse Architectural Tour. Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Map of the College – Peterhouse Cambridge".

- ^ "Peterhouse Images". Peterhouse, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ "Cambridge 2000: Peterhouse: Trumpington Street: St Peter's Terrace".

- ^ Peterhouse Annual Record 1999/2000

- ^ "Eminent". Petreans. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Halacy, Daniel Stephen (1970). Charles Babbage, Father of the Computer. Crowell-Collier Press. ISBN 0-02-741370-5.

External links

[edit] Media related to Peterhouse, Cambridge at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Peterhouse, Cambridge at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

Peterhouse, Cambridge

View on GrokipediaHistory

Foundation and Medieval Origins

Peterhouse, the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge, was established by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely, to provide structured residence and study for scholars amid tensions arising from Benedictine monks from Ely priory lodging disruptively in the town. In 1280, Balsham secured a royal licence from Edward I permitting the placement of a number of scholars within the Hospital of St John, initially numbering around sixteen and governed under the statutes of Merton College, Oxford. This arrangement formalized communal living, endowments, and oversight to ensure disciplined academic pursuit.[2] The formal foundation occurred in 1284 through two instruments dated 31 March, confirmed by a royal charter of Edward I, which authorized the relocation of these scholars from the hospital to the manor house known as Peterhouse, situated near Trumpington Gate. Balsham endowed the new foundation with the nearby church of St Peter and the rectory of Thriplow, providing initial revenues estimated at modest levels to support the master's stipend of 40 shillings annually and the fellows' maintenance. The college's statutes emphasized a rule of common life, with the master and scholars required to reside together, elect officers, and prioritize theological and arts studies, adapting Mertonian principles to the limited resources available.[2][5] In the subsequent medieval period, Peterhouse consolidated its position through incremental endowments and infrastructural growth. By the mid-14th century, under Bishop Simon Montacute of Ely, revised statutes in 1344 fixed the fellowship at fourteen, reflecting financial constraints while mandating celibacy, daily services, and progression from arts to theology. Revenues expanded modestly, with Thriplow rectory contributing about £40 of the college's £91 total income by 1374, supplemented by acquisitions like Wynwick’s Croft. Building efforts culminated in the early 15th century with the construction of a hall, chapel, and library—stocked with 380 volumes by 1418—and the initiation of Old Court’s west range in 1431, marking Peterhouse's transition from provisional hostels to a permanent medieval collegiate complex.[2]Early Modern Expansion and Reforms

In the sixteenth century, Peterhouse experienced administrative reforms and modest physical expansions under the long mastership of Andrew Perne (1554–1589), who secured benefactions from figures including Archbishop Matthew Parker and implemented measures such as the annual reading of college statutes, reduction of fellows' commons to 4d per week, and maintenance of eight poor scholars on foundation.[2] Student numbers grew substantially, from 26 undergraduates in 1542 to 154 by 1581, reflecting broader university trends amid the Reformation, though the college navigated religious shifts cautiously under Perne's opportunistic leadership, which preserved Catholic-leaning elements despite royal mandates.[2] The Old Court was completed during this period, while street-front houses fell into disrepair, limiting further building until later interventions.[2] The seventeenth century brought significant reforms and expansions under Matthew Wren (master 1625–1635), who demolished obsolete hostels, constructed a new chapel consecrated in 1632 in the Laudian style—featuring ornate furnishings and emphasizing ritualistic worship to counter Puritan austerity—and extended the Perne Library while adding new chambers and a perimeter wall.[2][6] Wren restructured fellowships to foster unity and imposed stricter discipline alongside John Cosin, aligning the college with high-church royalism; this stance led to Puritan occupations in the 1640s, during which the chapel was desecrated and stripped of altars and imagery before partial restoration post-1660.[2] In the eighteenth century, Peterhouse pursued property expansions, acquiring the Master's Lodge in 1727 and purchasing advowsons in 1731 and 1736 to bolster endowments, alongside constructing a new building in Ketton stone by 1741 and refacing the Old Court in 1754 for aesthetic and structural improvement.[2] Reforms under masters like Edmund Keene (1748–1754) shifted admissions toward wealthier students, prioritizing financial stability over traditional scholarly foundations, which sparked internal tensions culminating in a disputed mastership election in 1787 involving fellows and the Bishop of Ely.[2] These changes reflected the college's adaptation to Enlightenment-era priorities, emphasizing patronage and infrastructure over medieval statutes.[2]19th to 20th Century Developments

In the mid-19th century, Peterhouse underwent significant statutory reforms aligned with broader University of Cambridge changes to modernize governance and reduce clerical influence. In 1860, new statutes limited fellowships to 14, eliminated bye-fellowships, and established a dedicated scholarship fund to support academic talent.[2] Further reforms in 1878 abolished the mandate for at least three fellows to be in holy orders, reflecting declining Anglican dominance.[2] By 1882, statutes permitted married fellows and those outside the Church of England, while introducing six-year terms for fellowships to promote turnover and merit-based selection over lifelong tenure.[2] These changes, culminating in revised statutes in 1926, facilitated Peterhouse's adaptation to secular and professional academic norms, though the college maintained a conservative ethos compared to larger Cambridge institutions.[2] Physical infrastructure expanded modestly to accommodate growth, beginning with the 1817 bequest of £20,000 from Francis Gisborne, which funded the construction of Gisborne Court in 1825–1826 as additional student accommodation adjacent to the historic core.[2] Between 1866 and 1870, the medieval hall was reconstructed under Sir George Gilbert Scott, with interior decorations by William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, and Ford Madox Brown, enhancing ceremonial spaces while preserving Gothic elements.[2] Lord Kelvin, elected fellow in 1872, oversaw the installation of electric lighting in the hall and combination room in 1883–1884, an early adoption of the technology in Cambridge colleges.[2] In the 20th century, the New Hostel was built in 1925–1926 opposite the Master's Lodge, followed by a new lecture room in 1929 and Fen Court in 1940 at the site's western edge, providing further housing amid rising undergraduate numbers, which reached approximately 200 by 1954.[2] Academically, Peterhouse strengthened its reputation in natural sciences during this period, with fellows including Lord Kelvin (1872–) and briefly Sir James Dewar in the late 19th century, contributing to advancements in physics and thermodynamics.[2] The college's small size—around 20 fellows by mid-20th century, including seven professorial—fostered intensive mentorship, though it resisted broader University trends longer; women were not formally admitted as undergraduates until 1984, following statute changes in December 1983, making Peterhouse among the last Cambridge colleges to integrate female students.[2][7] This delay stemmed from internal conservatism, exemplified by opposition from figures like Master Hugh Lloyd-Jacob (1970–1978), prioritizing tradition over rapid coeducation.[8]Contemporary Era and Strategic Initiatives

In 2016, Bridget Kendall, a former BBC diplomatic correspondent, was elected as the first female Master of Peterhouse, serving until July 2023.[9] Her tenure emphasized maintaining the college's traditional ethos while navigating modern challenges, including enhanced international outreach and student welfare.[10] In 2023, Professor Andy Parker, a physicist specializing in high-energy particle physics and former head of the Cavendish Laboratory, succeeded her as Master, bringing expertise in scientific research leadership to guide the college's strategic direction.[11] Peterhouse's contemporary strategic initiatives center on a comprehensive masterplan commissioned to adapt historic infrastructure to 21st-century student and operational needs, such as evolving study habits, expanded archival storage, and improved social facilities.[12] Key projects include relocating the maintenance department to liberate space for new gardens and courts, converting underutilized bedrooms in existing housing into flexible social-study areas, and reconfiguring the library for enhanced ventilation and functionality.[12] Accessibility improvements, such as wheelchair access to the Master's Lodge, and the potential reopening of a medieval archway by reburying a 1950s kitchen extension, aim to preserve heritage while promoting sustainability and inclusivity.[12] The plan also integrates the return of Fitzwilliam House from university lease, optimizing it for additional academic and conference use to generate revenue.[12] Parallel efforts include the redevelopment of the college boathouse, designed to expand and modernize rowing facilities while respecting the site's environmental and visual constraints, such as river sightlines.[13] This initiative supports Peterhouse's ongoing emphasis on extracurricular traditions, particularly in sports, amid broader university trends toward facility upgrades.[13] These developments reflect a balanced approach to growth, prioritizing the college's compact scale—approximately 250 undergraduates and 100 postgraduates—without compromising its intimate, research-oriented community.[14]Physical Infrastructure

Historic Courts and Core Buildings

Old Court forms the historic core of Peterhouse, comprising the oldest surviving college quadrangle at the University of Cambridge, with construction phases spanning from the late 13th to the 15th century.[15] The south range, including the dining hall, was erected around 1290, making it the earliest such collegiate structure in regular use across the university.[16] This medieval hall features original timber elements and has undergone restorations, including electrical installation in the 19th century as one of the first buildings in Britain to adopt the technology after the Palace of Westminster.[17] The north range, consisting of staircases B, C, and D, dates to approximately 1424, while the west range incorporated a purpose-built library on its upper floor by 1450, later repurposed.[15] [18] The college chapel, a key core building, was constructed between 1628 and 1632 under the patronage of George Thompson and consecrated in 1632 during the mastership of Matthew Wren.[19] [6] Replacing an earlier medieval chapel, this structure exemplifies early 17th-century Gothic Revival elements and served as a center for Laudian liturgical practices amid university religious tensions.[20] An organ was installed by 1635, enhancing its role in college worship.[6] Gisborne Court adjoins Old Court to the east, forming part of the Grade I listed ensemble of historic buildings surrounding the original quadrangle, though its specific construction aligns with later medieval expansions rather than the foundational 13th-century phase.[21] The Master's Lodge, another enduring core edifice, was built in 1702 in Queen Anne style red brick and assumed its administrative function by 1727, providing continuity in governance amid evolving college needs.[22]Chapel, Library, and Specialized Facilities

The Chapel of Peterhouse, consecrated in 1632, replaced the earlier use of the nearby parish church of St Mary the Less and exemplifies 17th-century ecclesiastical architecture with its candlelit interior, intricate wood carvings, and some of Europe's finest stained glass windows.[23] [20] Designed under the influence of Laudian aesthetics during the mastership of John Cosin (1635–1642), it serves as a focal point for daily services, evensong by the Chapel Choir, and community events including Bible studies and annual retreats.[23] [20] The chapel houses a historic organ originally constructed by John Snetzler in 1765 as a GG-compass chamber organ, maintained by two Organ Scholars and supporting choral performances.[24] Peterhouse operates two main libraries: the Perne Library, a specialized research collection founded by the bequest of Andrew Perne (died 1589) comprising approximately 4,000 volumes focused on fine printing, illustrated books, and scientific classics, with extensions funded by Perne and later donations including around 800 volumes from John Cosin; and the Ward Library, an undergraduate facility opened in 1984 in a former Museum of Classical Archaeology building, holding over 65,000 volumes and equipped with study spaces, bookstands, laptop stands, and dimmable lamps for accessibility.[18] [25] [4] Special collections across the libraries include medieval and musical manuscripts—approximately 270 medieval volumes dating back to gifts from 1286 now deposited in the Cambridge University Library—along with modern manuscripts, photographs, member-published books, and comprehensive archives of college records from 1284 covering administration, finances, and East Anglian properties.[18] [26] Access to these specialized holdings requires appointments via the librarian or archivist, with digitized portions available through the Cambridge Digital Library.[26] Among other specialized facilities, the Whittle Building provides modern amenities including 22 en-suite student rooms, a gym, music practice rooms, a Junior Common Room, bar, and function spaces such as the Davidson Room, enhancing communal and recreational support for residents.[27] [28] The college's historic Theatre, seating 180, accommodates academic lectures, performances, and conferences, while library IT resources offer networked computers and accessibility aids for research.[29] [30]Grounds, Gardens, and Modern Extensions

Peterhouse's grounds feature several historic gardens that date back over 700 years, originally comprising a mix of cultivated plots and pasture land adjacent to the college's medieval core.[31] The Fellows' Garden, established as a formal walled enclosure in 1572, developed into its current layout by 1890, characterized by lawns, paths, and mature lime trees that dominate the space south of Old Court.[31] This garden serves as a quiet retreat for reflection and informal gatherings within the college community.[32] The Deer Park represents the largest expanse of the college grounds, with its northern portion acquired from former Friary land in 1295 and enclosed by a wall in 1501 to form 'The Grove.'[31] Deer were introduced in 1857, lending the name, though they were absent by the 1930s; during World War II, lime trees were felled to create vegetable plots and an orchard.[31] Today, it functions as an ornamental garden with wildflower areas, hosting garden parties and pre-dinner events.[33] The Scholars' Garden, purchased in 1569 as pasture known as Canons Close, transitioned to orchards and vegetable plots by the late 16th century and was formalized as 'New Gardens' by 1763 before subdivision in 1795.[31] Its western section remains the wildest, featuring a woodland fringe bordering Coe Fen Local Nature Reserve, enhancing biodiversity along the college's southern boundary.[34] Modern extensions have integrated sensitively with these historic grounds, notably the Whittle Building, designed by John Simpson Architects and opened in 2016, which completes the fourth side of the 19th-century Gisborne Court.[27] Named after alumnus Frank Whittle, inventor of the jet engine, the structure provides 22 student rooms, a junior common room, bar, gym, function room, music practice rooms, and a guest suite, enabling reconfiguration of older accommodations while maintaining architectural harmony.[35] Ongoing masterplanning efforts, including boathouse redevelopment for enhanced rowing facilities with ergometer training rooms and storage, continue to adapt peripheral grounds to contemporary student needs without compromising the site's heritage.[13][36]Academic Profile

Performance Metrics and Rankings

Peterhouse's undergraduate academic performance is evaluated through unofficial league tables such as the Tompkins Table, which aggregates final-year examination results across Cambridge triposes, assigning scores based on the proportion of first-class and upper-second-class degrees. In the 2024 Tompkins Table, Peterhouse ranked 15th out of 29 colleges, achieving a score of 67.84%, reflecting a solid but not elite position amid annual fluctuations driven by cohort size, subject mix, and exam difficulty.[37] Alternative metrics from the 2025 Baxter Table, calculated from official University of Cambridge classified examination data, position Peterhouse 10th overall, with a total score of 350.8 derived from outcomes including 84.5 first-class results, 130.5 upper seconds, and low numbers of lower classifications (25 seconds, 2 passes, 8 thirds) across approximately 250 classified students.[38] This ranking incorporates all course years and subjects, highlighting Peterhouse's competitive standing in aggregated empirical outcomes, though subject-specific tables show variability, with the college placing 10th in broader performance aggregates.[38] These tables underscore Peterhouse's consistent upper-midfield performance, with strengths in disciplines like natural sciences contributing to periodic top-ten finishes, but rankings remain sensitive to small undergraduate numbers (around 250-300) and do not capture graduate-level or research metrics.[38] The University of Cambridge provides raw examination dashboards for transparency, but discourages over-reliance on college-level aggregates due to inherent volatility.[39]Disciplinary Strengths and Intellectual Contributions

Peterhouse has historically exhibited strengths in the natural sciences, particularly physics, chemistry, and molecular biology, with alumni and fellows advancing foundational theories and experimental techniques. Henry Cavendish, a fellow from 1731, isolated hydrogen gas in 1766 and conducted the 1798 Cavendish experiment to measure Earth's density at 5.48 times that of water, establishing precise gravitational constants.[40] Lord Kelvin, affiliated in the 19th century, formulated the absolute temperature scale in 1848 and contributed to the second law of thermodynamics, while aiding the 1866 transatlantic telegraph cable's success through insulation innovations.[40] James Clerk Maxwell, a student and later influence, developed the equations unifying electricity and magnetism in 1865, underpinning modern electromagnetism.[41] In structural biology and biochemistry, Peterhouse fellows earned three Nobel Prizes in Chemistry and Physiology or Medicine during the 20th century for protein structure elucidation. John Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel in Chemistry for myoglobin's X-ray crystallographic determination, while Max Perutz received the same year's Physiology or Medicine Nobel for hemoglobin's structure, co-founding the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in 1962.[40] Aaron Klug won the 1982 Nobel in Chemistry for crystallographic electron microscopy of nucleic acid-protein complexes, enabling insights into viral structures.[40] These efforts established Peterhouse as a hub for interdisciplinary biological research, spanning three centuries of contributions to fields like island biodiversity and molecular mechanisms.[42][43] The college also maintains strengths in mathematics and computing precursors, with Charles Babbage designing the Difference Engine (conceived 1822, with 24,000 parts) and Analytical Engine (1830s, using punch-card programming), laying groundwork for programmable computers.[40] In humanities, Peterhouse has fostered conservative historiography, emphasizing religion, ideas, and political traditions; fellows like Maurice Cowling advanced analyses of 19th-century British intellectual history, critiquing Whig interpretations through works on Mill and the Tory tradition.[44] This approach, rooted in the college's post-1960s intellectual milieu, prioritized causal roles of elite agency over materialist determinism in historical causation.[45] Economics and law draw on rigorous analytical training, though less dominantly than sciences, with the college supporting core economic theory and international political history research.[46][47]Research Output and Innovations

Peterhouse has fostered research output primarily through its fellows and alumni, with notable strengths in physical sciences and molecular biology. Historical contributions include Henry Cavendish's isolation of hydrogen gas in 1766 while conducting experiments at his private laboratory, following his education at the college.[40] Lord Kelvin (William Thomson), another alumnus, advanced thermodynamics by proposing the absolute temperature scale in 1848 and contributed to the development of the transatlantic telegraph cable through cable theory in the 1860s.[40] Charles Babbage, who attended Peterhouse, conceptualized the Analytical Engine in the 1830s, laying foundational principles for modern computing via programmable difference engines.[40] In molecular biology, Peterhouse hosted four scientific Nobel laureates in the twentieth century: John Kendrew (Chemistry, 1962, for myoglobin structure), Aaron Klug (Chemistry, 1982, for nucleic acid-protein complexes), Archer Martin (Chemistry, 1952, for partition chromatography), and Max Perutz (Chemistry, 1962, for hemoglobin structure).[1] These affiliations underscored the college's role in structural biology advancements; between 1982 and the late 1990s, four Peterhouse fellows collectively held Nobel Prizes, enabling collaborative work on protein crystallography and biomolecular modeling at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology.[43] Contemporary research by Peterhouse fellows integrates into University of Cambridge initiatives, with strengths in natural sciences including physics, chemistry, and developmental genetics, though specific college-attributed outputs remain modest due to its small size of approximately 50 fellows.[48] The college supports stipendiary Research Fellows for three-year terms focused on independent projects, often in STEM fields, but quantifiable innovations are typically credited at the departmental level.[49] Peterhouse has hosted specialized conferences, such as the 2009 Research and Development in Intelligent Systems event, fostering advancements in AI applications.[50]Traditions and Symbols

Coat of Arms and Heraldry

The coat of arms of Peterhouse was formally granted on an unspecified date in 1575 by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms. This grant established the official heraldic bearings for the college, distinguishing it from informal or assumed arms used in earlier centuries. The design reflects the institution's foundation by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely, in 1284, incorporating elements derived from his personal heraldry.[51] The blazon of the arms is: Or, four pallets gules within a bordure of the last charged with eight crowns of the first. This translates to a golden field bearing four vertical red stripes (pallets), enclosed by a red border adorned with eight golden ducal coronets. The pallets are an augmentation of Balsham's attributed arms, which featured three such stripes on gold, symbolizing his episcopal lineage possibly linked to Catalan influences through Ely's historical ties. The charged bordure serves as a differencing element, preventing conflict with the founder's undifferenced arms and evoking royal or ecclesiastical authority via the coronets, though their precise origin remains unattributed in primary grants.[51][52] Historically, Peterhouse employed variant forms of its arms prior to the 1575 grant, including simpler versions without the full bordure charges; a 1684 heraldic visitation recorded a configuration with only three pallets. The current standardized version with four pallets and eight coronets has prevailed in official usage since the Renaissance grant, appearing on college seals, silverware, and architecture such as gateposts and chapel stained glass. This heraldry underscores the college's antiquity as Cambridge's oldest, emphasizing continuity from medieval foundations to modern institutional identity.[51]College Grace and Ceremonial Practices

Formal Hall at Peterhouse occurs every evening during Full Term, featuring a three-course candlelit meal served with waiter service, during which academic gowns must be worn by junior members.[53][54][55] Bookings are managed through the college's online system, with a fee of £7.20 deducted from student accounts, and guests permitted under specified limits.[53] The college grace, recited in Latin, forms a key ceremonial element of these dinners, beginning with "Benedic nos Domine, et dona Tua, quae de Tua largitate sumus..." Peterhouse employs a distinctive two-part grace structure, shared only with Jesus College among Cambridge colleges, comprising a standard preprandial prayer followed by a postprandial component.[56] Additional ceremonial practices include a matriculation feast held shortly after arrival for new undergraduates, requiring smart business attire in a moderately formal setting to induct students into college life.[57] The college also sustains traditions such as pennying during certain social dinners, governed by junior common room rules, though this is less formal than hall rituals.[58] Super-halls and special events, announced via the college portal, may incorporate enhanced ceremonial elements like themed menus or guest speakers.[53]Social and Cultural Norms

Peterhouse fosters a close-knit community due to its small size, with approximately 250 undergraduates and 150 postgraduates, enabling frequent interactions among students and fellows. This intimacy promotes a supportive environment where new arrivals integrate quickly, regardless of background, emphasizing academic dedication over social hierarchies.[59][60] Social norms prioritize formality and tradition, exemplified by near-daily formal hall dinners in the 13th-century hall, where students don gowns and adhere to structured seating and grace recitations, reinforcing collegiate identity and decorum. These practices, rooted in the college's medieval origins, contrast with more casual atmospheres at larger Cambridge colleges and cultivate a sense of pride and continuity.[61] Culturally, Peterhouse has historically maintained a conservative ethos, particularly evident in its 20th-century intellectual circles, such as the "Peterhouse school of history," associated with right-wing historiography and resistance to progressive reforms in the 1980s. While contemporary student life reflects broader university diversity, the college's legacy includes a reputation for intellectual independence and skepticism toward dominant academic orthodoxies, as noted in accounts of its fellows' opposition to modernization efforts.[8][62] This tradition informs ongoing norms of rigorous debate and unapologetic pursuit of scholarly rigor over ideological conformity.[63]Governance and Community

Administrative Structure and Leadership

The governance of Peterhouse is vested in the Governing Body, comprising the Master and all categories of Fellows—Official, Professorial, Supernumerary, and others—as defined by the college's statutes. This body holds ultimate authority over the management of college affairs, meeting at least once per term with decisions made by majority vote, the Master exercising a casting vote in ties. An Executive Council may be appointed by two-thirds vote of the Governing Body to exercise delegated powers on operational matters.[64] The Master serves as the ceremonial and administrative head, elected by the Governing Body for a fixed term of seven years, responsible for presiding over meetings, summoning the Governing Body, and promoting the college's welfare. Professor Andy Parker, a physicist and former Head of the Cavendish Laboratory, has held the position since 1 July 2023, succeeding Bridget Kendall.[65][11][64] Fellows form the academic core of the Governing Body, elected by majority vote for their scholarly contributions and good character; categories include Official Fellows (primarily teaching roles), Research Fellows (focused on independent research, typically for three years), Professorial Fellows (holding university chairs), and Supernumerary Fellows (additional appointments). The college maintains approximately 35-40 Fellows across disciplines such as physics, classics, economics, and history, ensuring a balance of teaching, research, and governance duties.[66][67][64] Key administrative officers, appointed by the Governing Body, support daily operations: the Senior Bursar oversees finances, investments, and estates, with Mr. Ian Wright in the role since 2013; the Domestic Bursar manages accommodations and services; Tutors handle undergraduate and graduate welfare; and the Dean leads chapel activities and pastoral care. These positions are pensionable and subject to Governing Body oversight, reflecting the college's emphasis on decentralized yet accountable leadership.[68][69][64]Student Demographics and Support Programs

Peterhouse maintains a relatively small student body of approximately 475 members, comprising around 240 undergraduates (with about 80 per year group) and 235 postgraduates.[59] Undergraduate admissions data for the 2024 cycle indicate a gender imbalance favoring male applicants and acceptances, with 315 total applications (64.7% male, 35.3% female), 75 offers (61.4% male, 38.6% female), and 58 acceptances (58.3% male, 41.7% female).[70] The majority of applicants are domestic, with 297 home applications out of 315 total (approximately 94%), reflecting a predominantly UK-based undergraduate intake; overseas applications constitute a small fraction, aligning with Peterhouse's emphasis on accessible proximity to central Cambridge facilities.[70]| Metric (2024 Cycle, Undergraduate) | Total | Male % | Female % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Applications | 315 | 64.7 | 35.3 |

| Offers | 75 | 61.4 | 38.6 |

| Acceptances | 58 | 58.3 | 41.7 |

![Charles Babbage Inventor of the difference engine, "Father of the computer"[43]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/CharlesBabbage.jpg/120px-CharlesBabbage.jpg)