Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Philippicae

View on Wikipedia

The Philippics (Latin: Philippicae, singular Philippica) are a series of 14 speeches composed by Cicero in 44 and 43 BC, condemning Mark Antony. Cicero likened these speeches to those of Demosthenes against Philip II of Macedon;[1] both Demosthenes' and Cicero's speeches became known as Philippics. Cicero's Second Philippic is styled after Demosthenes' On the Crown.

The speeches were delivered in the aftermath of the assassination of Julius Caesar, during a power struggle between Caesar's supporters and his assassins. Although Cicero was not involved in the assassination, he agreed with it and felt that Antony should also have been eliminated. In the Philippics, Cicero attempted to rally the Senate against Antony, whom he denounced as a threat to the Roman Republic.

The Philippics convinced the Senate to declare Antony an enemy of the state and send an army against him. However, the commanders were killed in battle, so the Senate's army came under the control of Octavian. When Octavian, Antony and Marcus Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate, Antony insisted that they proscribe Cicero in revenge for the Philippics. Cicero was hunted down and killed soon after.

Political climate

[edit]On 15 March 44 BC, Julius Caesar, the dictator of the Roman Republic, was assassinated by a group of Roman senators who called themselves Liberatores. Cicero was not recruited in the conspiracy and was surprised by it, even though the conspirators were confident of his sympathy. When Brutus, one of the conspirators, lifted his bloodstained dagger after the assassination, he called out Cicero's name, beseeching him to "restore the Republic!".[2] A letter Cicero wrote in February 43 BC to Trebonius, one of the conspirators, began, "How I wish that you had invited me to that most glorious banquet on the Ides of March!"[3]

Caesar had used his position to appoint his supporters to magistracies (which were normally elected positions) and promagistracies (which were usually assigned by the Senate). This was a clear violation of the Roman constitution and left Caesar's supporters, known as the Caesarian faction, vulnerable to their appointments being declared illegal by the Senate. Following the assassination, the Caesarians sought to legitimise their positions and to take revenge on the assassins.

With the Caesarians and supporters of the assassins deadlocked in the Senate, Cicero brokered a compromise: he arranged for the Senate to confirm Caesar's appointees in their posts and in exchange issue an amnesty for the assassins. This brought an uneasy peace between the factions, though it would last less than a year.

Cicero became a popular leader during the subsequent months of instability. He was opposed by Mark Antony, one of the consuls for 44 BC and the leader of the Caesarian faction. In private Cicero expressed his regret that the assassins had not eliminated Antony as well as Caesar. The two men had never been on friendly terms and their relationship worsened when Antony began acting as the unofficial executor of Caesar's will. Cicero made it clear that he felt Antony was misrepresenting Caesar's wishes and intentions for his own gain.

Octavian, Caesar's adopted son and heir, arrived in Italy in April and visited Cicero at his villa before heading to Rome. Sensing an opportunity, Cicero encouraged Octavian to oppose Antony.[4] In September Cicero began attacking Antony in a series of speeches that he called the Philippics in honour of his inspiration, Demosthenes' speeches denouncing Philip II of Macedon. Cicero lavished praise on Octavian, calling him a "god-sent child", claiming that the young man desired only honour and would not make the same mistakes as Caesar had.

During the period of the Philippics, Cicero's popularity as a public figure was unrivalled. He was appointed princeps senatus ('first man of the Senate') in 43 BC, becoming the first plebeian to hold the position. Cicero's attacks rallied the Senate to firmly oppose Antony, whom he called a "sheep". According to the historian Appian, for a few months Cicero "had the [most] power any popular leader could possibly have".[4]

Speeches

[edit]The fourteen speeches were:

- 1st Philippic (speech in the Senate, 2 September 44): Cicero criticises the legislation of the consuls in office, Mark Antony and Publius Cornelius Dolabella, who, he said, had acted counter to the will of the late Caesar (acta Caesaris). He demands that the consuls return to looking after the welfare of the Roman people.

- 2nd Philippic (pamphlet, conceived as a senatorial speech, 24 October 44,[5] possibly published only after the death of Cicero): Vehement attacks on Mark Antony, including the accusation that he surpasses in his political ambition even Lucius Sergius Catilina and Publius Clodius Pulcher. Catalogue of the "atrocities" of Mark Antony. It is the longest of Cicero's Philippics.

- 3rd Philippic (speech in the Senate, 20 December 44, in the morning): Fearing prosecution once his term as consul ends on 1 January, Antony has left Rome with an army, heading for Cisalpine Gaul. Cicero calls on the Senate to act against Antony, and demands that they show solidarity with Octavian and Decimus Brutus Albinus (one of Caesar's assassins who was now serving as the governor of Cisalpine Gaul).

- 4th Philippic (speech in the public assembly, 20 December 44, in the afternoon): Cicero denounces Mark Antony as a public enemy and argues that peace with Antony is inconceivable.

- 5th Philippic (speech in the Senate, held in the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus,[6] 1 January 43, in the presence of the new consuls Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa Caetronianus): Cicero urges the Senate not to send an embassy to Mark Antony and warns against Antony's intentions. Cicero proposes that the Senate honour Decimus Brutus, Octavian and his troops, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. Cicero's proposals are declined; the Senate sends the three ex-consuls Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, Lucius Marcius Philippus and Servius Sulpicius Rufus to Mark Antony.

- 6th Philippic (speech in the public assembly, 4 January 43): Cicero describes the embassy carried out by the Senate as merely delaying an inevitable declaration of war against Mark Antony. He believes war will come after the return of the ambassadors. He appeals for unanimity in the fight for freedom.

- 7th Philippic (speech in the Senate, outside the agenda, in mid-January 43): Cicero presents himself as an attorney of peace, but considers war against Mark Antony as a demand of the moment. Once more, he demands that negotiations with Mark Antony be discontinued.

- 8th Philippic (speech in the Senate, 3 February 43): Because Antony has turned down the demands of the Senate, Cicero concludes that the political situation is a de facto war. He would rather use the word bellum (war) than tumultus (unrest) to describe the current situation. He criticises the ex-consul Quintus Fufius Calenus, who wants to negotiate peace with Mark Antony: peace under him would be the same as slavery. He proposes amnesty to all soldiers that will leave Antony before 15 March 43, but those who stay with him later should be considered public enemies. The Senate agrees.

- 9th Philippic (speech in the Senate, 4 February 43): Cicero demands that the Senate honour Servius Sulpicius Rufus, who died during the embassy to Mark Antony. The Senate agrees to this proposal.

- 10th Philippic (speech in the Senate, in mid-February 43): Cicero praises the military deeds of Marcus Junius Brutus in Macedonia and Illyricum. He demands that the Senate confirm Brutus as the governor of Macedonia, Illyricum, and Greece together with the troops. The Senate agrees.

- 11th Philippic (speech in the Senate, end of February 43): Cicero castigates Dolabella for having murdered Gaius Trebonius, the governor of Asia. He demands that the governorship of Syria be given to Gaius Cassius Longinus. The Senate turns down this proposal.

- 12th Philippic (speech in the Senate, beginning of March 43): Cicero rejects a second embassy to Mark Antony, even though he was at first ready to participate in it. The Senate agrees.

- 13th Philippic (speech in the Senate, 20 March 43): Cicero attacks Antony for conducting war in North Italy (Antony was besieging Decimus Brutus in Mutina). He comments upon a letter of Antony to "Gaius Caesar" (Octavian) and Aulus Hirtius. He rejects the invitation to peace by Lepidus, referring to Antony's "crimes". He demands that the Senate honour Sextus Pompeius.

- 14th Philippic (speech in the Senate, 21 April 43, after the Senatorial victory over Antony at the Battle of Forum Gallorum): Cicero proposes a thanksgiving festival and praises the victorious commanders and their troops. He demands that Mark Antony be declared a public enemy (hostis). The Senate agrees to the latter proposal.

Lost and Fragmentary Speeches

[edit]In addition to the Philippics above, scholars are aware of six lost Philippics and one from which only a single sentence survives:

- De Pace ad Senatum (speech in the Senate, 17 May 44 BC).[7]

- De Pace ad Populum (speech in the public assembly, 17 or 18 May 44).[8]

- De imperatore adversus Dollabellum (speech in the public assembly, late February 43 immediately after the 11th Philippic).[9]

- De imperio Antoni (43).[10]

- In P. Servilium Isauricum (9 April 43).[11]

- In Antonium et Lepidum (43).[12]

- De liberis Lepidi (43).[13]

Analysis

[edit]The first two speeches mark the outbreak of the enmity between Mark Antony and Cicero. It is possible that Cicero wanted to invoke the memory of his successful denunciation of the Catiline conspiracy; at any rate, he compares Mark Antony with his own worst political opponents, Catiline and Clodius, in a clever rhetorical manner.

In the 3rd and 4th speeches, of 20 December 44, he tried to establish a military alliance with Octavian; the primary objective was the annihilation of Mark Antony and the restoration of the res publica libera – the free republic; to reach this goal, he favoured military means unambiguously.

As the Senate decided to send a peace delegation, in the 5, 6th, 7th, 8th and 9th speeches, he argued against the idea of an embassy and tried to mobilise the Senate and the Roman People to war.

In the 10th and 11th, he supports a military strengthening of the republicans Brutus and Cassius, but he was successful only in the case of Brutus.

In the 12th, 13th and 14th, he wanted to wipe out any doubt against his own war policy. After the victory over Mark Antony, in the last speech he still warns against a too prompt eagerness for peace.

Consequence

[edit]Cicero’s attacks on Antony were only partially successful and were overtaken by events on the battlefield. The Senate agreed with most (but not all) of Cicero's proposals, including declaring Antony an enemy of the state. Cicero convinced the two consuls for 43 BC, Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa, to lead the Senate's armies (with an allied force commanded by Octavian) against Antony. However, Pansa was mortally wounded at the Battle of Forum Gallorum, and Hirtius died at the Battle of Mutina a few days later. Both battles had been victories for the Senate army, but the deaths of its commanders left the force leaderless. The senior magistrate on the scene was Decimus Brutus (the propraetor of cisalpine Gaul), who the Senate attempted to appoint in command, but Octavian refused to work with him because he had been one of Julius Caesar's assassins. Most of the troops switched their loyalty to Octavian.

With Cicero and the Senate attempting to bypass him, and now in command of a large army, Octavian demanded that he be appointed suffect consul (filling the vacancy left by the deaths of Hirtius and Pansa), even though he was two decades younger than the legal minimum age. When the Senate declined, Octavian marched his army on Rome and occupied the city without resistance. He then forced through his election as suffect consul and began to reconcile with Antony. Antony and Octavian allied with each other and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate, in opposition to Caesar's assassins. With the triumvirate controlling almost all of the military forces in Italy and Gaul, they turned on Cicero and the Senate.

Immediately after legislating their alliance into official existence (for a five-year term with consular imperium), the triumvirate began proscribing their enemies and potential rivals. Cicero was proscribed, as was his younger brother Quintus Tullius Cicero (formerly one of Caesar's legati), and all of their supporters.[citation needed] They included a tribune named Salvius, who had sided with Antony before switching his support to Cicero. Octavian reportedly argued for two days against Cicero being added to the proscription list, but the triumvirs eventually agreed to each sacrifice one close associate (Cicero being Octavian's).[14]

Most of the proscribed senators sought to flee to the East, particularly to Macedonia where two more of Caesar's assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, were attempting to recruit new armies. Cicero was one of the most doggedly hunted of the proscribed, but was viewed with sympathy by a large segment of the public so many refused to report that they had seen him. He was eventually caught leaving his villa in Formiae in a litter heading for the coast, from where he hoped to embark on a ship to Macedonia.[15] He submitted to a soldier, baring his neck to him, suffering death and beheading. Antony requested that the hands that wrote the Philippics also be removed. His head and hands were publicly displayed in the Roman Forum to discourage any who would oppose the new Triumvirate of Octavian, Mark Antony, and Lepidus.

References

[edit]- ^ Cicero, Ad Atticus, 2.1.3

- ^ Cicero, Second Philippic Against Antony

- ^ Cicero, Ad Familiares 10.28

- ^ a b Appian, Civil Wars 4.19

- ^ cf. Cicero, Ad Atticum 15.13.1

- ^ Cicero, Marcus Tullius (2010). "Phillipic 5". In Bailey, D. R. Shackleton; Ramsey, John T.; Manuwald, Gesine (eds.). Philippics 1-6. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 189. Translated by Bailey, D. R. Shackleton. Harvard University Press. p. 241. doi:10.4159/DLCL.marcus_tullius_cicero-philippic_5.2010.

- ^ Jane W. Crawford, M. Tullius Cicero: The Lost and Unpublished Orations (Gottingen: Vanderhoeck & Ruprecht, 1984), pp. 244-247.

- ^ Crawford, 1984, pp. 248-249.

- ^ Crawford, 1984, pp. 250-251. See also Marcus Tullius Cicero, Philippics, edited and translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1986), p. 269.

- ^ Crawford, 1984, p.259.

- ^ Jane W. Crawford, M. Tullius Cicero, the Fragmentary Speeches: An Edition with Commentary, second edition (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1994), pp. 289-293.

- ^ Crawford, 1984, p.259.

- ^ Crawford, 1984, p.259.

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 46.3–5

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964) p. 293

Bibliography

[edit]- M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes tom. II. Recognovit brevique adnotatione critica instruxit Albertus Curtis Clark (Scriptorvm Classicorvm Bibliotheca Oxoniensis), typogr. ND der Ausgabe Oxford 2. Auflage 1918 [o.J].

- Marcus Tullius Cicero. Die politischen Reden, Band 3. Lateinisch-deutsch. Herausgegeben, übersetzt und erläutert von Manfred Fuhrmann, Darmstadt 1993.

- Stroh, Wilfried: "Ciceros Philippische Reden: Politischer Kampf und literarische Imitation." In: Meisterwerke der antiken Literatur: Von Homer bis Boethius, hrsg. von Martin Hose, München 2000, 76–102.

- Hall, Jon: "The Philippics", in: Brill's Companion to Cicero. Oratory and Rhetoric, hrsg. von James M. May, Leiden-Boston-Köln 2002, 273–304.

- Manuwald, Gesine: "Eine Niederlage rhetorisch zum Erfolg machen: Ciceros Sechste Philippische Rede als paradigmatische Lektüre", in: Forum Classicum 2 (2007) 90–97.

External links

[edit]- Philippics – Lexundria

- Perseus Project English translation Orations: The fourteen orations against Marcus Antonius (Philippics), C. D. Yonge, editor

- The Philippic Speeches in the Latin Library

The Philippics public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Philippics public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Philippicae

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Assassination of Julius Caesar

On March 15, 44 BC, Julius Caesar was assassinated in the Senate chamber at Pompey's Theatre in Rome by a conspiracy of approximately 60 senators, primarily led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. The plotters, styling themselves as liberatores (liberators), justified their actions as a defense of republican liberty against Caesar's perceived drift toward monarchy, citing his accumulation of unprecedented powers including the dictatorship for life declared earlier that year.[9] Empirical precedents fueling these fears included Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon River on January 10, 49 BC, with the 13th Legion, which defied the Senate's ultimatum and initiated civil war by subverting constitutional authority traditionally barring provincial armies from entering Italy proper.[10] This act, combined with subsequent victories that dismantled senatorial resistance under Pompey, enabled Caesar to pardon former enemies while centralizing control, as evidenced by his appointment as consul without election in 48 BC and extension of dictatorial powers beyond the customary six-month limit. The assassination unfolded during a scheduled Senate meeting when Caesar, unaccompanied by bodyguards despite warnings including the soothsayer's prophecy of the Ides of March, was surrounded and stabbed 23 times, with the first blow delivered by Tillius Cimber and the final by Brutus.[9] Caesar's refusal to wear armor or heed omens, rooted in his confidence from prior military successes, left him vulnerable; ancient accounts note his surprise at Brutus's involvement, reportedly uttering "You too, child?" (Et tu, Brute?) in Greek, underscoring the personal betrayal amid a plot that spared Caesar's co-consul Mark Antony after he was detained outside. The conspirators' failure to secure broader support or eliminate potential rivals immediately, however, prevented a clean restoration of senatorial dominance, as they underestimated public attachment to Caesar's reforms such as debt relief, calendar standardization, and colonial settlements that had empirically stabilized Rome post-civil war.[11] In the ensuing power vacuum, Antony, as surviving consul, assumed de facto control by securing Caesar's papers and will from his home, thereby inheriting administrative continuity while the assassins retreated to the Capitol amid mob unrest. Antony's funeral oration on March 20, delivered over Caesar's body in the Forum, inflamed passions by displaying the dictator's bloodied toga and invoking his will's bequests to the populace—including 300 sesterces per citizen and public gardens—causally shifting sentiment from shock to vengeful support for Caesar's legacy, destabilizing the Republic further by polarizing factions without resolving the underlying contest for supreme authority.[12] This event fragmented Roman elites, with the Senate initially granting amnesty to the conspirators via the so-called "pardon decree" on March 17, yet Antony's maneuvers exposed the fragility of republican institutions already eroded by Caesar's subversion of checks like tribunician vetoes and senatorial veto power. The assassination, intended to revive oligarchic balance, instead precipitated a cascade of alliances and wars that eroded the Senate's causal influence over executive decisions.Antony's Initial Moves and Senate Conflicts

Following the assassination of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BC, Mark Antony, as consul, convened the Senate on March 17 and negotiated a general amnesty for the conspirators, averting immediate civil strife while positioning himself as a mediator. With the aid of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Antony gained control over Caesar's private papers and correspondence, which he exploited to promulgate decrees retroactively attributed to Caesar, including validations of prior acts and distributions of public lands to Caesar's veterans from at least 16 legions.[13] This access allowed Antony to sway Senate votes by presenting measures as Caesar's unfulfilled intentions, thereby consolidating his influence over legislative outcomes and public resources.[14] Antony further leveraged Caesar's will, publicly read in late March, which bequeathed 300 sesterces to each Roman citizen and designated Caesar's gardens along the Tiber for public use, galvanizing popular support and enabling Antony to portray himself as the dictator's faithful executor. In May 44 BC, he pushed through allotments of ager publicus to settle thousands of veterans, drawing from Caesar's memoranda to justify encroachments on private holdings and straining Senate finances amid claims of misappropriating temple funds. These distributions, affecting properties in Italy, heightened tensions by favoring military loyalists over traditional property rights, as Antony bypassed full senatorial debate. Conflicts intensified with Publius Cornelius Dolabella, urban praetor, who vetoed Antony's initiatives, including in May 44 BC when Dolabella obstructed access to the Temple of Ops for archival purposes tied to Caesar's papers. By July, Antony's organization of the Ludi Apollinares in Caesar's honor—funded partly from state coffers—provoked Dolabella to declare them illegal, sparking riots that culminated in Dolabella's election as suffect consul on August 19, 44 BC, amid mutual accusations of electoral violence.[14] Provincial assignments exacerbated rifts; despite Senate confirmations in late April of Caesar's designations (e.g., Cisalpine Gaul to Decimus Brutus), Antony maneuvered in June via the Lex Antonia to claim Cisalpine Gaul for himself, exchanging it for Macedonia, against senatorial resistance that viewed it as undermining prior allocations. [15] Antony's military preparations underscored these disputes, as he recruited from Caesar's demobilized troops in Campania during summer 44 BC, amassing cohorts under the pretext of securing Italy against conspirator threats.[14] By November, after his final Senate address, Antony departed Rome for Brundisium with approximately 17 cohorts, then advanced toward Cisalpine Gaul to enforce his provincial claim against Decimus Brutus, signaling a shift from senatorial negotiation to armed enforcement that alarmed republican senators.[14] This northward maneuver, involving levies exceeding 3 legions' strength, positioned Antony to control key Alpine passes and veteran settlements, framing his actions as defensive yet eroding centralized Senate authority over military postings.[16]Broader Republican Crisis

The late Roman Republic's institutional framework was undermined by chronic land inequality, originating from the influx of wealth and slaves following conquests such as the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, which concentrated resources among senatorial elites and fueled the expansion of large estates known as latifundia. Small-scale citizen farmers, burdened by prolonged military service of three to five years during the late second century BC, increasingly lost their holdings to tax debts and elite acquisitions, resulting in rural depopulation, urban migration, and a swelling proletariat dependent on state grain distributions. Efforts to redress this, such as Tiberius Gracchus's Lex Agraria in 133 BC, which aimed to redistribute public land, provoked unprecedented senatorial vetoes and mob violence, culminating in his murder alongside 300 supporters, signaling the breakdown of consensual governance.[17] Military transformations exacerbated these fissures, as Gaius Marius's reforms in 107 BC eliminated property qualifications for legionary service, recruiting from the landless capite censi and standardizing equipment to create a professional standing army. This shift bound soldiers' allegiances to individual commanders who promised post-service land grants and bonuses, rather than to the abstract res publica, enabling generals to wield private armies for political ends. The precedent was starkly realized in Lucius Cornelius Sulla's march on Rome in 88 BC, igniting the first full-scale civil war (88–82 BC), followed by his dictatorship from 82 to 79 BC, during which proscriptions executed or exiled thousands of opponents, redistributing wealth but failing to restore stable senatorial dominance. These conflicts normalized the use of force against constitutional norms, priming the system for recurrent strongman interventions by eroding the separation between military command and civil authority.[18][19] The assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC intensified this decay, as the liberators—led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus—faced mounting hostility despite initial senatorial amnesty, prompting their flight from Rome to eastern provinces by early April 44 BC to levy troops among Roman garrisons and client kings. Concurrently, Caesar's grandnephew Gaius Octavius, adopted as heir in Caesar's will and later known as Octavian, learned of the murder while in Apollonia and swiftly returned to Brundisium in southern Italy around late April 44 BC, where he mobilized Caesar's veterans and asserted claims to his inheritance amid Antony's interim control of the city. This fragmentation highlighted entrenched factionalism between optimates defending senatorial prerogatives and populares leveraging popular assemblies, compounded by the erosion of mos maiorum—ancestral customs emphasizing restraint and precedent—which had yielded to raw ambition and extralegal violence, as evidenced by the Gracchi killings and Sullan purges that accustomed elites to bypassing deliberative processes.[20][17]Cicero's Reentry into Politics

Personal Motivations and Philosophical Rationale

Cicero's opposition to Antony stemmed from a longstanding preference for otium—intellectual leisure and philosophical study—over the perils of negotium, or public engagement, a tension evident in his letters to Atticus spanning from 68 to 43 BC, where he repeatedly weighed withdrawal against republican duty following his consulship in 63 BC and exile in 58 BC.[21] By 44 BC, after Julius Caesar's dictatorship had marginalized the Senate, Cicero resided at his villa near Naples, avoiding Rome amid Antony's consolidation of power post-assassination on March 15, 44 BC.[22] This retirement reflected not mere altruism but empirical self-preservation, as active politics had previously endangered his life and property, yet the post-Caesarian vacuum compelled his return to defend institutions tied to his status as a leading orator and senator. Philosophically, Cicero's rationale rooted in his advocacy for a mixed constitution in De Re Publica (c. 51 BC), positing the ideal res publica as "the property of the people" sustained by justice, utility, and balance among monarchical, aristocratic, and democratic elements to prevent tyranny.[23] He viewed Antony's maneuvers—such as manipulating Caesar's acts and bypassing senatorial consent—as eroding this equilibrium, akin to the tyrants critiqued in the dialogue's Somnium Scipionis, where true statesmen prioritize communal welfare over personal dominance.[24] This framework justified resistance, including implicit endorsement of tyrannicide as a restorative act, aligning with Cicero's causal view that unchecked autocracy inevitably corrupts the common good, as evidenced by Caesar's prior subversion of republican norms. Personal grievances amplified these incentives, including Antony's pre-Philippic verbal attacks on Cicero's absence from Senate sessions in April 44 BC and threats to his Tusculan villa, alongside broader encroachments via land commissions that risked senatorial estates.[25] Cicero framed such hostilities not as petty vendettas but as symptomatic of Antony's unfitness, threatening the senatorial restoration essential for Cicero's influence, wealth, and safety—outcomes empirically linked to republican revival rather than heroic self-sacrifice.[26] His writings underscore a pragmatic calculus: preserving the Senate's authority safeguarded his novus homo ascent and philosophical legacy against demagogic rivals.[27]Strategic Positioning Against Antony

In the months following Julius Caesar's assassination on 15 March 44 BC, Cicero initially hesitated to reengage in public life, traveling between his villas while monitoring developments through correspondence, such as letters to Titus Pomponius Atticus, which revealed his growing alarm at Mark Antony's consolidation of power via decrees from Caesar's acta. By mid-summer 44 BC, Cicero shifted to active coalition-building, targeting Senate moderates disillusioned with both the Liberators' violence and Antony's authoritarian tendencies, aiming to restore senatorial authority without endorsing extralegal actions.[28] Central to this strategy were alliances with Caesarian moderates, notably the consuls-designate for 43 BC, Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa Caetronianus, whom Cicero had befriended during Caesar's dictatorship and who shared intelligence on Antony's provincial maneuvers and financial manipulations.[29] These ties, cultivated via private meetings and exchanges emphasizing shared republican values over personal loyalty to Caesar, positioned Cicero as a bridge between optimate traditionalists and pragmatic Caesarians, contrasting Antony's perceived demagoguery. Cicero also engaged Gaius Octavius, Caesar's young heir, whom he met near Naples in April 44 BC and initially groomed as a senatorial counterweight to Antony, encouraging Octavian's adoption of pro-republican stances in exchange for legitimacy.[30] Deliberately distancing himself from the Liberators—such as Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, whose flight from Italy after amnesty failures risked alienating centrists—Cicero advocated procedural senatorial opposition, framing Antony's control of legions and the treasury as unconstitutional usurpation rather than justifying regicide.[31] This moderation, evident in his selective praise of the assassins' motives while prioritizing Senate decrees, helped polarize alignments by mid-August 44 BC, drawing waverers toward a constitutionalist bloc amid Antony's preparations for provincial governorships.[15] Cicero's return to Rome around 1 August 44 BC marked the culmination of these preparations, enabling discreet consultations with senators and oratorical groundwork for upcoming assemblies, where his influence exacerbated factional tensions by legitimizing resistance without provoking immediate civil strife.[32]Composition and Delivery of the Speeches

Philippic I: The Opening Salvo

On September 2, 44 BC, Cicero delivered the First Philippic (Philippica I) before the Roman Senate in the Temple of Tellus, convened by consul Publius Cornelius Dolabella while Mark Antony was absent from Rome.[25][7] This marked Cicero's cautious return to senatorial debate after months of withdrawal following Julius Caesar's assassination on March 15, 44 BC, amid tensions from Antony's consolidation of power through ratification of Caesar's acts and retention of loyalist forces.[33] The speech functioned as a probing critique, blending commendation of Antony's early post-assassination moderation with veiled warnings against authoritarian drift, intended to assess senatorial resolve without provoking immediate rupture.[34] Cicero opened by accounting for his prior absences from Senate sessions, attributing them to Antony's entourages of armed men that intimidated attendance and undermined deliberative freedom, thereby highlighting the erosion of traditional senatorial autonomy.[35] He praised Antony's funeral oration for Caesar as judicious, crediting it alongside mediation by Antony's sons with securing a tenuous peace and general amnesty that averted reprisals against Caesar's assassins.[33] Notably, Cicero lauded Antony's oath to uphold Caesar's acts—sworn publicly on March 17, 44 BC—followed by the consuls' arrangement to burn Caesar's unpublished memoranda, a move that neutralized potentially tyrannical or self-serving provisions and preserved constitutional integrity.[34] These elements framed Antony as potentially redeemable if adherent to republican precedents. The oration's critical edge targeted Antony's deviations from ancestral norms (mos maiorum), particularly his refusal to disband Caesar's cohort of approximately 6,000 gladiators repurposed as a private bodyguard, which Cicero depicted as an illegal aggregation evoking monarchical peril rather than consular propriety.[36] He urged Antony to eschew Caesar's errors, such as perpetual dictatorship, by deferring to senatorial decrees on provincial assignments and military commands, emphasizing that true consular authority derived from collective deliberation, not personal armaments.[35] This restrained rebuke avoided outright invective, positioning Antony's trajectory as reversible through adherence to liberty (libertas) and the Republic's foundational laws. In conclusion, Cicero exhorted senatorial unity to reclaim legislative primacy, invoking the collective duty of conscripti patres to safeguard the res publica against factional overreach, while professing his own commitment to concord: "in which temple, I... laid the foundations of peace."[35] This conciliatory tone, prioritizing reconciliation over confrontation, aimed to rally moderates and test Antony's receptivity to constitutional restraint, distinguishing the speech as an initial sounding rather than a declaration of war.[36]Philippic II: The Written Denunciation

The Second Philippic was composed by Cicero in the autumn of 44 BC, shortly after Mark Antony's hostile speech against him in the Senate on 19 September 44 BC, during which Cicero was absent from Rome.[5] Unlike the First Philippic delivered on 2 September 44 BC, this second oration was never orally presented but crafted as a literary pamphlet for private circulation among senators and influential Romans to galvanize opposition to Antony's consolidating power.[4] Its dramatic date is set to coincide with Antony's 19 September address, framing it as a direct rebuttal, though actual finalization occurred in late November or early December 44 BC.[4] In the speech, Cicero launches a comprehensive invective tracing Antony's vices from adolescence through his consulship in 44 BC, portraying him as inherently corrupt and unfit for leadership.[4] He accuses Antony of youthful debauchery, including scandalous sexual conduct such as prostituting himself to Gaius Scribonius Curio and engaging in extravagant, licentious behavior that squandered family resources.[37] Cicero further alleges chronic financial irresponsibility, claiming Antony accrued massive debts—exceeding six million sesterces by age 25—through gambling and dissipation, then evaded creditors via legal maneuvers and false oaths.[38] As consul, Cicero charges Antony with betraying Julius Caesar's legacy by posthumously altering or suppressing decrees, seizing state funds, and mismanaging Caesar's will and estate for personal gain, actions that undermined the late dictator's intentions and enriched Antony illicitly.[39] These empirical claims, drawn from public records and Antony's documented career, serve to discredit his authority and equate his ambitions with tyrannical overreach.[4] The speech's publication represented a pivotal escalation in Cicero's rhetorical strategy, shifting from the conciliatory tone of the First Philippic to an unyielding denunciation that branded Antony as a public enemy aspiring to monarchy.[5] By forgoing delivery in the Senate—where Antony's influence risked disruption—circulation allowed Cicero to build a case among allies without immediate reprisal, though it yielded no direct political outcomes amid the post-assassination instability.[4] This undelivered text thus functioned as a foundational manifesto for Cicero's subsequent Philippics, solidifying his commitment to republican restoration against Antony's perceived autocracy.[5]

Philippics III to XIV: Intensifying Campaigns

The Third Philippic, delivered on 4 December 44 BC, defended the senate's issuance of the senatus consultum ultimum against Mark Antony, portraying it as a necessary measure to preserve the republic amid Antony's military maneuvers toward Cisalpine Gaul.[40] Cicero highlighted Decimus Brutus's refusal to yield the province, which Caesar had assigned to him, and exhorted the senate to rally provincial governors and allies against Antony's advance with a depleted legion.[40] This speech marked a shift toward explicit endorsement of armed resistance, framing Antony's actions as tantamount to civil war.[41] Philippics IV through VI, delivered in January 43 BC, responded directly to Antony's letters presented to the senate, critiquing his demands for provincial reassignments and financial concessions.[42] In the Fourth, Cicero rejected Antony's claims to Macedonia for his brother Lucius, arguing such grants undermined senatorial authority over provinces.[43] The Fifth proposed declaring a state of emergency (tumultus) to mobilize forces without embassy negotiations, emphasizing Antony's rejection of reconciliation.[44] Philippic VI further dismantled Antony's justifications for army movements, accusing him of plundering Italy and subverting consular elections.[45] These orations intensified rhetorical pressure, grouping Antony's kin and allies as collective threats while advocating immediate levies.[46] From Philippics VII to XIV, spanning late January to 21 April 43 BC, Cicero urged formal alliance with Gaius Octavius (later Augustus), condemning Dolabella for the murder of consul Trebonius in Asia and pushing declarations of war against Antony.[47] Philippic VII opposed embassies to Antony, labeling them futile given his siege of Decimus Brutus at Mutina.[48] In the Eleventh, Cicero praised Octavius's mobilization of Caesar's veterans, recommending senatorial ratification of his imperium to counter Antony's forces.[49] Philippic XII, delivered in early March, refused Cicero's participation in a second delegation, insisting on treating Antony as a public enemy and allocating funds for legions under consuls Pansa and Hirtius.[50] The Thirteenth targeted Dolabella's atrocities, while the Fourteenth, on 21 April, reviewed senatorial decrees empowering Octavius and the consuls, directly precipitating the Mutina engagements where republican legions clashed with Antony's army.[47] These speeches empirically escalated from denunciation to logistical support, correlating with senate votes for 10 legions and supplies against Antony's estimated 17 legions.[41]Lost, Fragmentary, and Questioned Texts

Ancient sources preserve fragments from Philippics beyond the fourteen extant orations, indicating that Cicero composed or delivered additional speeches in the series against Antony. For instance, Arusianus Messius quotes a fragment from the Seventeenth Philippic: "That disagreement has not been decided by war," in a context discussing unresolved conflicts.[51] Nonius Marcellus attributes another to the Fourth Philippic, though distinct from the surviving text: "What? Does this decree of the senate cause you to remove yourself from the city in secret?"[52] These citations suggest further orations existed, possibly extending the sequence to at least seventeen, though no complete texts survive.[53] Asconius Pedianus, in his first-century AD commentaries on Cicero's speeches, references thematic elements from lost or partially attested Philippics, including Antony's strategic intentions in Gaul, such as proposed military maneuvers and provincial governance.[54] These scholia provide contextual fragments rather than extended passages, often rearranging excerpts for explanatory purposes rather than preserving original order.[53] Quintilian alludes to the Philippics collectively in his rhetorical analyses but does not enumerate a total, focusing instead on their stylistic vigor without specifying lost components.[55] The authenticity of the Fourteenth Philippic, delivered around April 43 BC after the Battle of Mutina, has faced scrutiny among some scholars due to perceived stylistic inconsistencies with earlier Philippics and its emphasis on praising consuls Gaius Vibius Pansa and Aulus Hirtius for republican victories, which may reflect post-battle adjustments not fully aligning with Cicero's prior invective tone.[56] However, ancient attributions, including in manuscript traditions, support its Ciceronian origin, with debates centering on historical fit rather than outright forgery.[47] No conclusive evidence disproves its genuineness, and it remains included in standard editions alongside the others.[57]Rhetorical and Thematic Content

Invective Against Antony's Character and Actions

In the Philippicae, Cicero systematically assailed Mark Antony's personal character, portraying him as a morally corrupt figure whose vices rendered him incapable of legitimate authority, thereby positioning him as a natural successor to Caesar's autocracy through incompetence and brutality rather than merit. Central to this was the Second Philippic, where Cicero cataloged Antony's early life as marked by prostitution and dependency, claiming he offered sexual services to Gaius Scribonius Curio at a fixed price to fund his indulgences, a relationship that allegedly continued into adulthood with Antony assuming a subservient role. [58] These accusations drew on publicly known associations and financial dependencies verifiable through Antony's documented debts and Curio's political favors, though Antony later dismissed them as fabrications in his responsive orations.[59] Cicero extended the invective to Antony's chronic debauchery, alleging habitual public drunkenness, including vomiting in the Roman Forum amid spectacles of excess, and all-night gambling sessions that squandered fortunes like Pompey's estate in mere days. He cited specific instances, such as Antony's occupation of Varro's villa for orgiastic revels involving prostitutes and hirelings from the third hour of the day, contrasting this with the property's prior scholarly use and supported by the absence of any legal auction records. Antony's ties to convicted gamblers like Licinius Lenticula, whom he reinstated, underscored his own immersion in such vices, with Cicero referencing senate records of Antony's financial manipulations to sustain them. Historical accounts corroborate elements of Antony's profligacy, including his reliance on loans and provincial tributes to offset gambling losses, though the scale of Cicero's depictions amplified rhetorical effect over precise quantification.[60] On criminal actions, Cicero accused Antony of multiple murders and violent assaults, including an attempted killing of Publius Clodius Pulcher during gang confrontations and the execution of Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus post-Pharsalus, framing these as symptoms of unchecked aggression. He further charged Antony with plundering Italy through illegal sales of public lands, exemptions from Caesar's decrees, and falsified documents authorizing seizures, amassing personal wealth while bankrupting the state—evidenced by Antony's own ledgers of transactions and complaints from affected municipalities like Teanum Sidicinum. In later Philippics, such as the thirteenth, Cicero reiterated Antony's armed retinues terrorizing Italian towns to enforce tribute, citing witness testimonies from local elites. Antony countered by invoking his military service under Caesar and attributing Cicero's claims to partisan enmity, but senate deliberations post-44 BCE partially validated the financial abuses through annulled sales.[61] These attacks collectively aimed to erode Antony's claim to Caesarian legitimacy by causal linkage: personal depravity bred political rapacity, making his rule a predictable descent into tyranny unsupported by evidence of restraint or public benefit.[58]Defense of Republican Principles

In the Philippicae, Cicero articulated a defense of republican principles by invoking the traditional authority of the Roman Senate as the guardian of the res publica. Delivered on 2 September 44 BC, Philippic I emphasized the Senate's role in restoring constitutional order after Julius Caesar's dictatorship, asserting that the commonwealth had submitted to senatorial judgment and authority following Caesar's death.[7][25] In section 33, Cicero questioned whether Antony regretted his prior actions in defense of the state, implying that true consular duty aligned with senatorial oversight rather than personal ambition, thereby reinforcing the separation of powers inherent in the mixed constitution.[62] This appeal to ancestral precedents and the rule of law positioned the Senate as the embodiment of Rome's mos maiorum, distinct from monarchical overreach.[63] Cicero critiqued one-man rule as the primary cause of civil discord, drawing parallels to historical dictators like Sulla, whose proscriptions and unchecked power had destabilized the Republic in 82–79 BC. He warned that Antony's consolidation of legions and provincial commands echoed Sulla's path to autocracy, which had invited retaliation and ongoing strife rather than stability. In Philippic V, Cicero referenced the laws of war and ancestral customs to argue against Antony's violations of constitutional limits, portraying such dominance as antithetical to the balanced governance that prevented factional violence.[64] This analysis rooted republican endurance in distributed authority, where individual supremacy inevitably eroded collective liberty and invited cycles of vengeance. Integrating Stoic philosophy, Cicero justified resistance to tyranny through the concept of natural law, positing that actions contrary to reason and the common good warranted opposition to preserve the eternal principles of justice. In the Philippicae, he extended this to Antony's unconstitutional maneuvers, arguing that senatorial decrees aligned with ius naturale overrode tyrannical edicts, as seen in appeals framing defense of the Republic as a moral imperative beyond positive law.[65][66] This framework elevated republican resistance from mere politics to a philosophical duty, underscoring that true sovereignty resided in rational order rather than force.

Appeals to Historical Precedents and Allies

In the Philippics, Cicero invoked the suppression of Lucius Sergius Catilina's conspiracy in 63 BC as a precedent for decisive senatorial action against internal threats to the republic. As consul, he had secured a senatus consultum ultimum authorizing the execution of conspirators without trial, a measure he portrayed as essential to preempting violent overthrow; he contrasted this timely intervention with the perils of hesitation, which he argued allowed demagogues like Antony to consolidate gladiatorial bands and provincial resources.[67][68] Cicero extended such appeals by lauding the assassins of Julius Caesar—termed liberatores—as contemporary models of republican defense, likening their act on the Ides of March 44 BC to Lucius Junius Brutus's expulsion of Tarquinius Superbus around 509 BC, which ended regnal tyranny. In Philippic I, delivered September 2, 44 BC, he cited the spontaneous applause for Marcus Junius Brutus at the Ludi Apollinares as public validation of tyrannicide, warning that exiling these figures would repeat ancestral errors of tolerating despots.[7][69] References to Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus served as pragmatic exemplars of lawful command against chaos, with Cicero recalling Pompey's suppression of the Sertorian revolt in Hispania (77–72 BC) and pirate campaigns (67 BC) to underscore disciplined military loyalty to the Senate over personal ambition. In Philippic I, he tied Pompey's enactments to stable governance, implying Antony's disregard for such precedents risked similar breakdowns.[70][71] To build coalitions, Cicero pragmatically urged support from key contemporaries, emphasizing shared stakes in averting Antony's encirclement of loyalists. In Philippic XIII, pronounced March 20, 43 BC, he implored consuls Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa to deploy their intact legions against Antony's siege of Decimus Brutus at Mutina, portraying their hesitation as a causal enabler of blockade success. He appealed to Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus's veteran cohorts, including the Legio Martia and Legio IV, highlighting the young commander's forces numbering several thousand as pivotal for rapid relief, detached from Caesar's legacy. Extensions reached provincial allies like Lucius Munatius Plancus in Gallia Comata, whose reinforcements Cicero framed as replicating Catilinarian-era mobilizations to isolate rebels.[61][72][73] These invocations stressed causality rooted in history: precedents like the Catilinarian executions demonstrated that prompt allied unity forestalled entrenched power, whereas delay—as in tolerating early signs of Caesar's dominance—invited irreversible tyranny by permitting arms accumulation and loyalty shifts.[74][75]Immediate Consequences

Senate Responses and Declarations of Antony as Enemy

Following Cicero's First Philippic on September 2, 44 BC, the Senate issued a measured response, voting a supplication to the gods for three days in recognition of the republic's deliverance from Caesar's tyranny but refraining from direct condemnation of Antony, reflecting caution amid his control of consular armies and recent reconciliation gestures.[25] This endorsement implicitly aligned with Cicero's call for senatorial vigilance without provoking immediate rupture, as Antony's forces encircled Decimus Brutus in Cisalpine Gaul.[7] The Third Philippic, delivered on December 20, 44 BC, marked a turning point, with Cicero's rhetoric—emphasizing Antony's violations of senatorial decrees and threats to provincial commands—prompting the Senate to pass resolutions endorsing Octavian's suppression of a mutinous legion loyal to Antony and granting him command of two additional legions previously assigned to the consuls.[76] These decrees rejected Antony's overtures for peace negotiations and affirmed Decimus Brutus's governorship of Cisalpine Gaul, countering Antony's claims to the province; Cicero's logic framed such concessions as capitulation to tyranny, swaying hesitant senators like Pansa against accommodation. On January 1, 43 BC, as consuls Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa entered office, the Senate enacted the senatus consultum ultimum, an emergency decree empowering the consuls and proconsuls to employ any measures necessary to preserve the state against Antony's perceived aggression, including military mobilization without further consultation.[77] This action, directly influenced by Cicero's prior speeches linking Antony's troop movements to dictatorial ambitions, authorized the allocation of consular armies to Hirtius for Transalpine Gaul and Pansa for subsequent support, while denying Antony's demands for troop reinforcements or provincial extensions. Debates under Cicero's guidance dismissed Antony's envoys' proposals for arbitration, viewing them as delays enabling encirclement of republican forces.Escalation to Civil War and Triumvirate

The Philippicae catalyzed the Senate's issuance of the senatus consultum ultimum on December 20, 44 BC, following the Third Philippic, empowering consuls to wage war against Antony as a threat to the state.[40] This decree mobilized consular armies under Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa, with Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Octavian) providing auxiliary legions, leading to confrontations at Forum Gallorum on April 14, 43 BC, and Mutina on April 21, 43 BC.[78] The senatorial forces secured tactical victories, relieving the besieged Decimus Brutus at Mutina and forcing Antony's legions to retreat, though both consuls perished—Hirtius in combat at Mutina and Pansa from wounds sustained earlier—rendering the outcome pyrrhic and exposing the fragility of republican military efforts.[78] Antony, undeterred, conducted an orderly withdrawal across the Alps, evading annihilation and linking with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in Gaul by late June 43 BC, whose seven legions bolstered Antony's position and shifted momentum toward triumviral negotiations. Octavian, whose troops had been pivotal at Mutina, received insufficient rewards from the Senate—despite Cicero's advocacy for his propraetorian status—he defied senatorial authority by marching eleven legions on Rome in early August 43 BC, compelling the consular elections and assuming the consulship on August 19 at age 19. This maneuver eroded the senatorial consensus that the Philippicae had fortified, as Octavian prioritized personal power over the anti-Antony coalition Cicero envisioned. The power vacuum and mutual threats—Antony's recovering forces versus Octavian's urban control—drove secret talks, culminating in the Second Triumvirate's formation near Bononia on November 27, 43 BC, when Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus divided provinces and legions under the subsequent Lex Titia, granting them extraordinary imperium for five years.[79] To finance their alliance and eliminate opposition, the triumvirs enacted proscriptions starting December 43 BC, confiscating property from over 300 senators and 2,000 equestrians, with Antony explicitly demanding Cicero's inclusion as vengeance for the Philippicae's vituperations against his character and legitimacy. This retaliatory mechanism empirically connected Cicero's rhetorical escalation to the policy reversals that entrenched triumviral dictatorship, overriding Octavian's initial reluctance.Cicero's Fate and the Speeches' Role

Cicero was proscribed and executed on December 7, 43 BC, during the Second Triumvirate's reign of terror, which targeted over 300 senators and 2,000 equestrians to consolidate power and fund armies. Fleeing by sea from his villa near Formiae, he was intercepted by the centurion Herennius and tribune Popillius, Antony's agents; his head and right hand—the one that penned the Philippicae—were severed and nailed to the Rostra in the Forum as trophies of vengeance.[80] Antony's mutilation of the hand explicitly symbolized retribution for the speeches' invective, which had branded him a tyrant akin to Demosthenes' foe Philip II. The Philippicae formed a direct causal link in this outcome, escalating a preexisting feud—stemming from Cicero's suppression of the Catilinarian conspiracy, which executed Antony's stepfather Lentulus—into irreconcilable enmity.[81] In November 43 BC, during Triumvirate negotiations at Bononia, Antony conditioned his alliance with Octavian and Lepidus on Cicero's proscription, overriding Octavian's initial reluctance and leveraging the speeches' personal barbs as justification.[82] The orations' relentless attacks on Antony's morality, debts (exceeding 100 million sesterces by Cicero's tally), and alleged tyrannical seizures had rallied senatorial forces, prompting Antony's outlawry in late 44 BC and an abortive consular army against him.[5] Yet this mobilization inadvertently hastened Octavian's pivot to Antony, as battlefield contingencies favored triumviral unity over republican restoration, culminating in Cicero's isolation. Scholars debate the speeches' decisiveness: the Philippicae's survival has amplified perceptions of their provocation, but Antony's precondition suggests they tipped an already hostile balance, with restraint potentially extending Cicero's shelter under Octavian's early patronage amid shifting alliances. Without them, Antony's demands might have lacked such pointed leverage, given the orations' role in galvanizing opposition that forced the Triumvirate's concessions; however, deeper structural contingencies—like Caesar's legacy and military realities—likely rendered Cicero expendable regardless, as proscriptions served fiscal and factional ends beyond personal scores.[83] The irony persists: Cicero's words mobilized anti-Antony sentiment effectively enough to declare him hostis publicus, yet failed to forestall the dictatorship's renewal through triumviral absolutism, sealing the orator's fate in the process he decried.[5]Legacy and Reception

Transmission and Medieval Survival

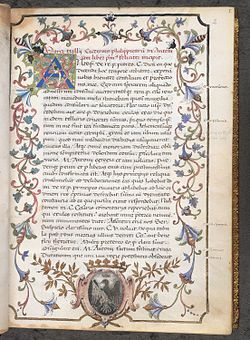

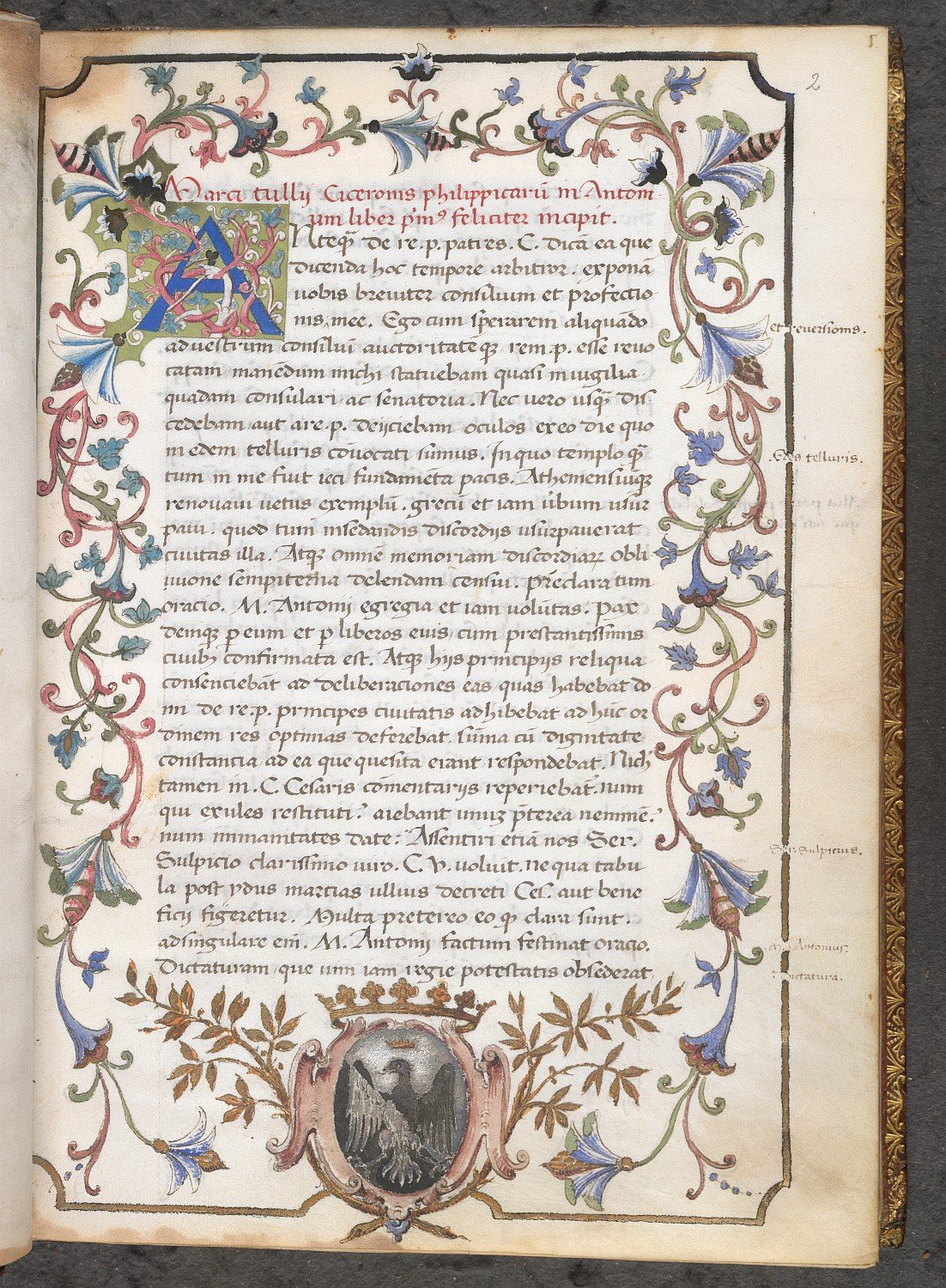

The Philippicae were disseminated in written form shortly after their composition in 44–43 BC, with Cicero himself overseeing the publication of several speeches, including the undelivered Second Philippic, while his secretary Marcus Tullius Tiro likely compiled and edited the collection posthumously following Cicero's execution in December 43 BC.[84] Circulation remained limited during the early Roman Empire due to the proscription of Cicero and suppression of anti-Antonian materials under the Second Triumvirate and Augustan regime, resulting in few surviving ancient exemplars.[7] Transmission across late antiquity was precarious amid the decline of Roman infrastructure and barbarian invasions, with many classical texts lost or fragmented; however, monastic communities preserved select copies of Cicero's works, including the Philippicae, through scriptorial copying efforts.[85] The Carolingian Renaissance under Charlemagne (c. 780–814 AD) revitalized this tradition, as scholars like Alcuin of York promoted the collection and reproduction of Roman authors in centers such as Tours, Corbie, and Fulda, yielding 9th-century manuscripts containing Cicero's orations.[85] A notable example is a 9th-century Tours manuscript preserving multiple Ciceronian speeches, exemplifying the archetype from which later medieval copies derive.[85] Medieval manuscript families for the Philippicae divide into Italian and northern (often French or German) branches, with no pre-9th-century codices extant; key witnesses include Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, lat. 5802 (13th century) from the Colotian family and earlier Carolingian-derived texts influencing the stemma codicum.[86] Preservation relied on ecclesiastical institutions like Monte Cassino, where Cicero's rhetorical corpus, including the Philippicae, was valued for educational purposes in grammar and rhetoric, ensuring textual continuity despite sporadic omissions or interpolations in copies.[87] By the 15th century, illuminated manuscripts such as British Library Kings MS 21 attest to ongoing scribal interest, bridging to early printed editions in the 16th century based on these medieval sources.[88]Renaissance Rediscovery and Influence

Francesco Petrarch, in the 14th century, engaged deeply with Cicero's Philippicae, citing them alongside works like De Officiis as exemplars of vehement oratory against political adversaries, though he critiqued Cicero's immersion in partisan strife over philosophical detachment.[89] Petrarch's familiarity with the speeches, including references to their hostile tone toward Antony, contributed to early humanist admiration for Cicero's defense of republican liberty amid threats of autocracy.[90] In the early 15th century, Poggio Bracciolini advanced the textual tradition by producing an autograph manuscript of the Philippicae (Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Plut. 48.22), which facilitated emendations and the editio princeps around 1469–1470, enhancing their accessibility for Renaissance scholars.[91] [92] This revival positioned the speeches as a rhetorical model for humanist orators confronting monarchical overreach, emphasizing Cicero's invectives as tools for upholding civic virtues and resisting tyranny.[93] The Philippicae influenced Niccolò Machiavelli's republican thought, informing his Discourses on Livy where Cicero's staunch opposition to Antony paralleled arguments for vigilant citizen defense against ambitious leaders eroding constitutional balances.[93] Desiderius Erasmus, while prioritizing Ciceronian prose in his Ciceronianus (1528), drew on the speeches' anti-tyrannical themes to advocate eloquent public discourse favoring republican principles over absolutism in humanist education.[94] By modeling resistance to Caesarism—equating Antony's power grabs with threats to senatorial authority—the Philippicae causally shaped Enlightenment rhetoric on liberty, providing precedents for thinkers contrasting constitutional governance with despotic consolidation, as seen in later invocations of Ciceronian liberty against monarchical pretensions.[95] [96]Modern Scholarly Assessments

Modern scholars generally regard Cicero's Philippicae as exemplary invective oratory, showcasing his mastery of rhetorical techniques such as vituperatio and historical analogy, yet as a political instrument that accelerated rather than averted the Republic's collapse. In the 20th century, the speeches received limited attention compared to Cicero's earlier works, with assessments emphasizing their literary brilliance—particularly the Second Philippic's scathing character assassination of Antony—over any strategic efficacy, as they failed to consolidate senatorial opposition amid Caesar's lingering popularity.[97][98] This view posits a causal disconnect: while the orations galvanized a factional response, including declarations against Antony, they underestimated the military realities post-Caesar, contributing to the senatus consultum ultimum's ineffectiveness and the subsequent triumvirate.[99] Recent 21st-century scholarship, building on textual editions like Gesine Manuwald's, reevaluates the Philippicae through their philosophical underpinnings, framing them not merely as ad hominem attacks but as articulations of republican mos maiorum against monarchical overreach. Katharina Volk's analysis situates the speeches within the intellectual milieu of "senator-scholars," highlighting how Cicero integrated Stoic ethics and historical erudition to defend constitutional order, though this depth did little to sway outcomes dominated by power dynamics. Empirical historiography underscores the orations' long-term influence in vilifying Antony—shaping narratives in Livy and Plutarch—contrasting sharply with their immediate failure, as senatorial decrees yielded to Octavian's alliance with Antony by November 43 BCE.[46] Assessments remain balanced, with proponents viewing Cicero as a principled defender of elite-guided liberty against demagoguery, crediting the speeches for momentarily restoring senatorial agency after Caesar's assassination. Critics, however, highlight an elitist bias, arguing the Philippicae dismissed popular sentiments favoring stability under strongmen, prioritizing optimate restoration over pragmatic reform and thus alienating broader support. This causal realism reveals the orations' rhetorical potency in elite circles but ultimate futility against entrenched militarism, as evidenced by Cicero's proscription and execution on December 7, 43 BCE.[31]Controversies and Scholarly Debates

Cicero's Objectivity and Personal Biases

Cicero's longstanding personal animosity toward Mark Antony stemmed from events dating to 63 BCE, when, as consul, Cicero ordered the summary execution of several Catilinarian conspirators, including Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, Antony's stepfather following his mother's remarriage.[81] This act, while defended by Cicero as necessary to avert a coup, engendered enduring resentment in Antony, who later cited it as a foundational grudge in his retaliatory speeches. Plutarch records that Antony's mother Julia's marriage to Lentulus positioned the executed conspirator as a paternal figure, amplifying the familial dimension of the enmity that colored Cicero's later invective. Such biographical details underscore how Cicero's Philippicae were not detached analyses but extensions of a decades-old vendetta, prioritizing rhetorical vilification over impartial chronicle. In the Second Philippic, Cicero levels lurid accusations of Antony's youthful debauchery, portraying him as a public prostitute who donned a woman's toga and serviced clients, particularly the tribune Curio, for financial gain before Curio "ransomed" him into exclusivity. Contemporary historians recognize these claims as adhering to the conventions of Roman invective, where imputations of prostitution served to emasculate political rivals rather than convey literal biography; no independent corroboration exists for Antony engaging in paid sex work, though his early extravagance and debts are attested. Plutarch, drawing on multiple sources, depicts Antony's adolescence as marked by dissipation and indebtedness but emphasizes his innate martial aptitude and rapid redemption through military service under Caesar, contrasting Cicero's one-dimensional caricature. Similarly, Cicero's allegation of Antony's assault on Publius Clodius Pulcher lacks substantiation beyond the orator's narrative, with scholarly analysis suggesting it as fabricated or inflated to impugn Antony's character during the 50s BCE Bona Dea scandal aftermath.[100] Cicero's prior political accommodations further reveal opportunism beneath his republican posturing. Following Caesar's victory at Pharsalus in 48 BCE, Cicero, who had aligned with Pompey, surrendered without resistance and accepted Caesar's unsolicited clemency, returning to Italy and engaging in correspondence that sought reconciliation and favor from the dictator.[101] Letters from this period, such as those in Ad Familiares, demonstrate Cicero's pragmatic flattery toward Caesar, whom he had once opposed vehemently. After Caesar's assassination on March 15, 44 BCE, Cicero initially endorsed amnesty for conspirators but swiftly pivoted to assail Antony, Caesar's designated heir, as a tyrant— a shift Antony exploited by publicizing excerpts of Cicero's pro-Caesar missives in Senate speeches to expose the orator's inconsistency. Antony's rejoinders, preserved fragmentarily, framed Cicero as a fickle trimmer who bent to power when expedient, undermining the Philippicae's pretense of principled consistency. As a rhetorician trained in ars topica, Cicero privileged persuasive amplification over evidentiary rigor, rendering the speeches potent polemic but unreliable as unvarnished history.Effectiveness in Halting Tyranny

Cicero's Philippicae, delivered between September 44 BC and April 43 BC, achieved limited short-term political successes by mobilizing senatorial opposition to Mark Antony. Following the Fourteenth Philippic on April 21, 43 BC, the Senate authorized consular armies under Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa to confront Antony's forces besieging Decimus Brutus in Mutina, culminating in the Battle of Mutina on the same day, where republican legions inflicted heavy casualties on Antony—estimated at over 20,000 killed or wounded—forcing his retreat northward toward Gaul.[36][32] These outcomes stemmed directly from Cicero's rhetorical pressure, which secured decrees declaring Antony a public enemy (hostis publicus) in December 44 BC and allocating funds for military levies, temporarily halting Antony's consolidation of power in Cisalpine Gaul.[25][102] However, these gains proved ephemeral due to underlying military and political realities that oratory alone could not alter. The deaths of Hirtius and Pansa at Mutina left Octavian in command of the victorious forces, yet the Senate's failure to grant him full authority—coupled with its reluctance to pursue Antony aggressively—allowed the latter to regroup with legions in Transalpine Gaul by June 43 BC.[32] Empirical evidence from the era underscores that Antony commanded approximately 17 legions and Caesar's veteran loyalty, dwarfing senatorial resources, which prioritized legalistic resistance over sustained warfare; Cicero's reliance on senatorial decrees without commensurate force backing exposed the republic's institutional fragility post-Caesar's assassination.[22] By August 43 BC, Octavian's independent march on Rome to claim the consulship bypassed Cicero's influence, paving the way for the Second Triumvirate's formation on November 27, 43 BC, which redistributed power among Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus, rendering the Philippicae's anti-tyrannical stance moot.[103] Critics argue the speeches exacerbated the republic's collapse by provoking Antony without viable countermeasures, accelerating polarization in a context where military allegiance, not rhetoric, determined outcomes. Scholarly analyses contend that Cicero's uncompromising invective alienated potential moderates and pushed Antony toward alliance with Octavian, whose ambitions Cicero misjudged; had negotiation prevailed—perhaps ratifying Antony's governorships as in Caesar's settlements—the republican framework might have endured longer amid ongoing civil strife.[32][22] Realist perspectives emphasize causal factors like the republic's prior erosion from 50 years of intermittent civil wars (e.g., Sulla's proscriptions in 82 BC and Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BC), which had entrenched legions' loyalty to generals over the Senate, rendering Cicero's efforts a futile stand against inevitable autocracy.[104] Optimistic interpretations frame the Philippicae as a moral victory in defending res publica principles against tyranny, inspiring later republican resistance despite tactical failure, though such views often prioritize ideological intent over empirical results.[105] In aggregate, the speeches' ineffectiveness in averting empire highlights oratory's subordination to force in late republican dynamics, with Antony's survival and the triumvirs' proscriptions—culminating in Cicero's execution on December 7, 43 BC—confirming the triumph of pragmatic power alliances.[106][32]Alternative Viewpoints from Antony's Supporters

Supporters of Mark Antony, as depicted in ancient accounts, framed his leadership as a continuation of Julius Caesar's populares reforms, which emphasized land redistribution and debt relief for the masses, positioning Antony against what they viewed as the self-interested assassins and their senatorial allies. Appian reports that Antony initially sought compromise by proposing amnesty for Caesar's killers while upholding the dictator's acts, efforts his followers saw as stabilizing the republic amid chaos wrought by elite intrigue rather than tyrannical ambition. These partisans criticized Cicero's Philippicae as inflammatory rhetoric designed to sabotage peace negotiations and rally the optimates elite against popular will, portraying the orator as a reactionary obstructing Caesar's legacy of empowering veterans and the plebs. In Appian's narrative, Antony's soldiers explicitly blamed Cicero for instigating war by opposing Antony's interests, interpreting the speeches as elite propaganda that ignored the broader consensus favoring continuity with Caesar's policies over senatorial restoration. Empirical support for this stance lay in Antony's control of Caesar's loyal legions, including the Martia and Fourth legions, which defected to him in significant numbers by early 43 BC, reflecting deference from troops who prioritized martial patronage and reforms over decrees from a senate perceived as detached from military realities. Plutarch notes Antony's early command of multiple cohorts and his ability to muster veteran forces, which his backers cited as evidence of genuine popular and soldiery endorsement transcending Cicero's senatorial appeals.References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Manuscript_of_Cicero_-_BL_Kings_MS_21_f._2.jpg