Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Computer virus

View on Wikipedia

A computer virus[1] is a type of malware that, when executed, replicates itself by modifying other computer programs and inserting its own code into those programs.[2][3] If this replication succeeds, the affected areas are then said to be "infected" with a computer virus, a metaphor derived from biological viruses.[4]

Computer viruses generally require a host program.[5] The virus writes its own code into the host program. When the program runs, the written virus program is executed first, causing infection and damage. By contrast, a computer worm does not need a host program, as it is an independent program or code chunk. Therefore, it is not restricted by the host program, but can run independently and actively carry out attacks.[6][7]

Virus writers use social engineering deceptions and exploit detailed knowledge of security vulnerabilities to initially infect systems and to spread the virus. Viruses use complex anti-detection/stealth strategies to evade antivirus software.[8] Motives for creating viruses can include seeking profit (e.g., with ransomware), desire to send a political message, personal amusement, to demonstrate that a vulnerability exists in software, for sabotage and denial of service, or simply because they wish to explore cybersecurity issues, artificial life and evolutionary algorithms.[9]

As of 2013, computer viruses caused billions of dollars' worth of economic damage each year.[10] In response, an industry of antivirus software has cropped up, selling or freely distributing virus protection to users of various operating systems.[11]

History

[edit]The first academic work on the theory of self-replicating computer programs was done in 1949 by John von Neumann who gave lectures at the University of Illinois about the "Theory and Organization of Complicated Automata". The work of von Neumann was later published as the "Theory of self-reproducing automata". In his essay von Neumann described how a computer program could be designed to reproduce itself.[12] Von Neumann's design for a self-reproducing computer program is considered the world's first computer virus, and he is considered to be the theoretical "father" of computer virology.[13]

In 1972, Veith Risak directly building on von Neumann's work on self-replication, published his article "Selbstreproduzierende Automaten mit minimaler Informationsübertragung" (Self-reproducing automata with minimal information exchange).[14] The article describes a fully functional virus written in assembler programming language for a SIEMENS 4004/35 computer system. In 1980, Jürgen Kraus wrote his Diplom thesis "Selbstreproduktion bei Programmen" (Self-reproduction of programs) at the University of Dortmund.[15] In his work Kraus postulated that computer programs can behave in a way similar to biological viruses.

The Creeper virus was first detected on ARPANET, the forerunner of the Internet, in the early 1970s.[16] Creeper was an experimental self-replicating program written by Bob Thomas at BBN Technologies in 1971.[17] Creeper used the ARPANET to infect DEC PDP-10 computers running the TENEX operating system.[18] Creeper gained access via the ARPANET and copied itself to the remote system where the message, "I'M THE CREEPER. CATCH ME IF YOU CAN!" was displayed.[19] The Reaper program was created to delete Creeper.[20]

In 1982, a program called "Elk Cloner" was the first personal computer virus to appear "in the wild"—that is, outside the single computer or computer lab where it was created.[21] Written in 1981 by Richard Skrenta, a ninth grader at Mt. Lebanon High School near Pittsburgh, it attached itself to the Apple DOS 3.3 operating system and spread via floppy disk.[21] On its 50th use the Elk Cloner virus would be activated, infecting the personal computer and displaying a short poem beginning "Elk Cloner: The program with a personality."

In 1984, Fred Cohen from the University of Southern California wrote his paper "Computer Viruses – Theory and Experiments".[22] It was the first paper to explicitly call a self-reproducing program a "virus", a term introduced by Cohen's mentor Leonard Adleman.[23] In 1987, Cohen published a demonstration that there is no algorithm that can perfectly detect all possible viruses.[24] Cohen's theoretical compression virus[25] was an example of a virus which was not malicious software (malware), but was putatively benevolent (well-intentioned). However, antivirus professionals do not accept the concept of "benevolent viruses", as any desired function can be implemented without involving a virus (automatic compression, for instance, is available under Windows at the choice of the user). Any virus will by definition make unauthorised changes to a computer, which is undesirable even if no damage is done or intended. The first page of Dr Solomon's Virus Encyclopaedia explains the undesirability of viruses, even those that do nothing but reproduce.[26][27]

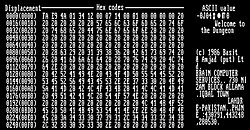

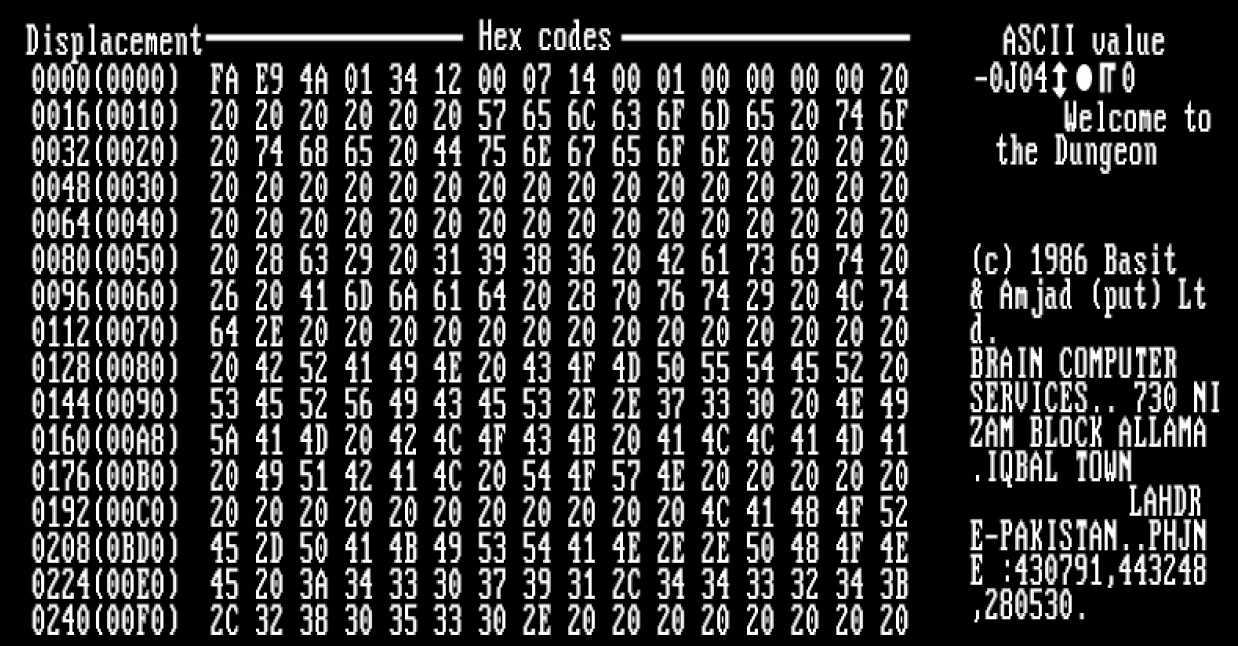

An article that describes "useful virus functionalities" was published by J. B. Gunn under the title "Use of virus functions to provide a virtual APL interpreter under user control" in 1984.[28] The first IBM PC compatible virus in the "wild" was a boot sector virus dubbed (c)Brain,[29] created in 1986 and was released in 1987 by Amjad Farooq Alvi and Basit Farooq Alvi in Lahore, Pakistan, reportedly to deter unauthorized copying of the software they had written.[30]

The first virus to specifically target Microsoft Windows, WinVir was discovered in April 1992, two years after the release of Windows 3.0.[31] The virus did not contain any Windows API calls, instead relying on DOS interrupts. A few years later, in February 1996, Australian hackers from the virus-writing crew VLAD created the Bizatch virus (also known as "Boza" virus), which was the first known virus to specifically target Windows 95.[32] This virus attacked the new portable executable (PE) files introduced in Windows 95.[33] In late 1997 the encrypted, memory-resident stealth virus Win32.Cabanas was released—the first known virus that targeted Windows NT (it was also able to infect Windows 3.0 and Windows 9x hosts).[34]

Even home computers were affected by viruses. The first one to appear on the Amiga was a boot sector virus called SCA virus, which was detected in November 1987.[35] By 1988, one sysop reportedly found that viruses infected 15% of the software available for download on his BBS.[36]

Design

[edit]Parts

[edit]A computer virus generally contains three parts: the infection mechanism, which finds and infects new files, the payload, which is the malicious code to execute, and the trigger, which determines when to activate the payload.[37]

- Infection mechanism

- Also called the infection vector, this is how the virus spreads. Some viruses have a search routine, which locate and infect files on disk.[38] Other viruses infect files as they are run, such as the Jerusalem DOS virus.

- Trigger

- Also known as a logic bomb, this is the part of the virus that determines the condition for which the payload is activated.[39] This condition may be a particular date, time, presence of another program, size on disk exceeding a threshold,[40] or opening a specific file.[41]

- Payload

- The payload is the body of the virus that executes the malicious activity. Examples of malicious activities include damaging files, theft of confidential information or spying on the infected system.[42][43] Payload activity is sometimes noticeable as it can cause the system to slow down or "freeze".[38] Sometimes payloads are non-destructive and their main purpose is to spread a message to as many people as possible. This is called a virus hoax.[44]

Phases

[edit]Virus phases is the life cycle of the computer virus, described by using an analogy to biology. This life cycle can be divided into four phases:

- Dormant phase

- The virus program is idle during this stage. The virus program has managed to access the target user's computer or software, but during this stage, the virus does not take any action. The virus will eventually be activated by the "trigger" which states which event will execute the virus. Not all viruses have this stage.[38]

- Propagation phase

- The virus starts propagating, which is multiplying and replicating itself. The virus places a copy of itself into other programs or into certain system areas on the disk. The copy may not be identical to the propagating version; viruses often "morph" or change to evade detection by IT professionals and anti-virus software. Each infected program will now contain a clone of the virus, which will itself enter a propagation phase.[38]

- Triggering phase

- A dormant virus moves into this phase when it is activated, and will now perform the function for which it was intended. The triggering phase can be caused by a variety of system events, including a count of the number of times that this copy of the virus has made copies of itself.[38] The trigger may occur when an employee is terminated from their employment or after a set period of time has elapsed, in order to reduce suspicion.

- Execution phase

- This is the actual work of the virus, where the "payload" will be released. It can be destructive such as deleting files on disk, crashing the system, or corrupting files or relatively harmless such as popping up humorous or political messages on screen.[38]

Targets and replication

[edit]Computer viruses infect a variety of different subsystems on their host computers and software.[45] One manner of classifying viruses is to analyze whether they reside in binary executables (such as .EXE or .COM files), data files (such as Microsoft Word documents or PDF files), or in the boot sector of the host's hard drive (or some combination of all of these).[46][47]

A memory-resident virus (or simply "resident virus") installs itself as part of the operating system when executed, after which it remains in RAM from the time the computer is booted up to when it is shut down. Resident viruses overwrite interrupt handling code or other functions, and when the operating system attempts to access the target file or disk sector, the virus code intercepts the request and redirects the control flow to the replication module, infecting the target. In contrast, a non-memory-resident virus (or "non-resident virus"), when executed, scans the disk for targets, infects them, and then exits (i.e. it does not remain in memory after it is done executing).[48]

Many common applications, such as Microsoft Outlook and Microsoft Word, allow macro programs to be embedded in documents or emails, so that the programs may be run automatically when the document is opened. A macro virus (or "document virus") is a virus that is written in a macro language and embedded into these documents so that when users open the file, the virus code is executed, and can infect the user's computer. This is one of the reasons that it is dangerous to open unexpected or suspicious attachments in e-mails.[49][50] While not opening attachments in e-mails from unknown persons or organizations can help to reduce the likelihood of contracting a virus, in some cases, the virus is designed so that the e-mail appears to be from a reputable organization (e.g., a major bank or credit card company).

Boot sector viruses specifically target the boot sector and/or the Master Boot Record[51] (MBR) of the host's hard disk drive, solid-state drive, or removable storage media (flash drives, floppy disks, etc.).[52]

The most common way of transmission of computer viruses in boot sector is physical media. When reading the VBR of the drive, the infected floppy disk or USB flash drive connected to the computer will transfer data, and then modify or replace the existing boot code. The next time a user tries to start the desktop, the virus will immediately load and run as part of the master boot record.[53]

Email viruses are viruses that intentionally, rather than accidentally, use the email system to spread. While virus infected files may be accidentally sent as email attachments, email viruses are aware of email system functions. They generally target a specific type of email system (Microsoft Outlook is the most commonly used), harvest email addresses from various sources, and may append copies of themselves to all email sent, or may generate email messages containing copies of themselves as attachments.[54]

Detection

[edit]To avoid detection by users, some viruses employ different kinds of deception. Some old viruses, especially on the DOS platform, make sure that the "last modified" date of a host file stays the same when the file is infected by the virus. This approach does not fool antivirus software, however, especially those which maintain and date cyclic redundancy checks on file changes.[55] Some viruses can infect files without increasing their sizes or damaging the files. They accomplish this by overwriting unused areas of executable files. These are called cavity viruses. For example, the CIH virus, or Chernobyl Virus, infects Portable Executable files. Because those files have many empty gaps, the virus, which was 1 KB in length, did not add to the size of the file.[56] Some viruses try to avoid detection by killing the tasks associated with antivirus software before it can detect them (for example, Conficker). A Virus may also hide its presence using a rootkit by not showing itself on the list of system processes or by disguising itself within a trusted process.[57] In the 2010s, as computers and operating systems grow larger and more complex, old hiding techniques need to be updated or replaced. Defending a computer against viruses may demand that a file system migrate towards detailed and explicit permission for every kind of file access.[citation needed] In addition, only a small fraction of known viruses actually cause real incidents, primarily because many viruses remain below the theoretical epidemic threshold.[58]

Read request intercepts

[edit]While some kinds of antivirus software employ various techniques to counter stealth mechanisms, once the infection occurs any recourse to "clean" the system is unreliable. In Microsoft Windows operating systems, the NTFS file system is proprietary. This leaves antivirus software little alternative but to send a "read" request to Windows files that handle such requests. Some viruses trick antivirus software by intercepting its requests to the operating system. A virus can hide by intercepting the request to read the infected file, handling the request itself, and returning an uninfected version of the file to the antivirus software. The interception can occur by code injection of the actual operating system files that would handle the read request. Thus, an antivirus software attempting to detect the virus will either not be permitted to read the infected file, or, the "read" request will be served with the uninfected version of the same file.[59]

The only reliable method to avoid "stealth" viruses is to boot from a medium that is known to be "clear". Security software can then be used to check the dormant operating system files. Most security software relies on virus signatures, or they employ heuristics.[60][61] Security software may also use a database of file "hashes" for Windows OS files, so the security software can identify altered files, and request Windows installation media to replace them with authentic versions. In older versions of Windows, file cryptographic hash functions of Windows OS files stored in Windows—to allow file integrity/authenticity to be checked—could be overwritten so that the System File Checker would report that altered system files are authentic, so using file hashes to scan for altered files would not always guarantee finding an infection.[62]

Self-modification

[edit]Most modern antivirus programs try to find virus-patterns inside ordinary programs by scanning them for so-called virus signatures.[63] Different antivirus programs will employ different search methods when identifying viruses. If a virus scanner finds such a pattern in a file, it will perform other checks to make sure that it has found the virus, and not merely a coincidental sequence in an innocent file, before it notifies the user that the file is infected. The user can then delete, or (in some cases) "clean" or "heal" the infected file. Some viruses employ techniques that make detection by means of signatures difficult but probably not impossible. These viruses modify their code on each infection. That is, each infected file contains a different variant of the virus.[citation needed]

One method of evading signature detection is to use simple encryption to encipher (encode) the body of the virus, leaving only the encryption module and a static cryptographic key in cleartext which does not change from one infection to the next.[64] In this case, the virus consists of a small decrypting module and an encrypted copy of the virus code. If the virus is encrypted with a different key for each infected file, the only part of the virus that remains constant is the decrypting module, which would (for example) be appended to the end. In this case, a virus scanner cannot directly detect the virus using signatures, but it can still detect the decrypting module, which still makes indirect detection of the virus possible. Since these would be symmetric keys, stored on the infected host, it is entirely possible to decrypt the final virus, but this is probably not required, since self-modifying code is such a rarity that finding some may be reason enough for virus scanners to at least "flag" the file as suspicious.[citation needed] An old but compact way will be the use of arithmetic operation like addition or subtraction and the use of logical conditions such as XORing,[65] where each byte in a virus is with a constant so that the exclusive-or operation had only to be repeated for decryption. It is suspicious for a code to modify itself, so the code to do the encryption/decryption may be part of the signature in many virus definitions.[citation needed] A simpler older approach did not use a key, where the encryption consisted only of operations with no parameters, like incrementing and decrementing, bitwise rotation, arithmetic negation, and logical NOT.[65] Some viruses, called polymorphic viruses, will employ a means of encryption inside an executable in which the virus is encrypted under certain events, such as the virus scanner being disabled for updates or the computer being rebooted.[66] This is called cryptovirology.

Polymorphic code was the first technique that posed a serious threat to virus scanners. Just like regular encrypted viruses, a polymorphic virus infects files with an encrypted copy of itself, which is decoded by a decryption module. In the case of polymorphic viruses, however, this decryption module is also modified on each infection. A well-written polymorphic virus therefore has no parts which remain identical between infections, making it very difficult to detect directly using "signatures".[67][68] Antivirus software can detect it by decrypting the viruses using an emulator, or by statistical pattern analysis of the encrypted virus body. To enable polymorphic code, the virus has to have a polymorphic engine (also called "mutating engine" or "mutation engine") somewhere in its encrypted body. See polymorphic code for technical detail on how such engines operate.[69]

Some viruses employ polymorphic code in a way that constrains the mutation rate of the virus significantly. For example, a virus can be programmed to mutate only slightly over time, or it can be programmed to refrain from mutating when it infects a file on a computer that already contains copies of the virus. The advantage of using such slow polymorphic code is that it makes it more difficult for antivirus professionals and investigators to obtain representative samples of the virus, because "bait" files that are infected in one run will typically contain identical or similar samples of the virus. This will make it more likely that the detection by the virus scanner will be unreliable, and that some instances of the virus may be able to avoid detection.

To avoid being detected by emulation, some viruses rewrite themselves completely each time they are to infect new executables. Viruses that utilize this technique are said to be in metamorphic code. To enable metamorphism, a "metamorphic engine" is needed. A metamorphic virus is usually very large and complex. For example, W32/Simile consisted of over 14,000 lines of assembly language code, 90% of which is part of the metamorphic engine.[70][71]

Effects

[edit]Damage is due to causing system failure, corrupting data, wasting computer resources, increasing maintenance costs or stealing personal information.[10] Even though no antivirus software can uncover all computer viruses (especially new ones), computer security researchers are actively searching for new ways to enable antivirus solutions to more effectively detect emerging viruses, before they become widely distributed.[72]

A power virus is a computer program that executes specific machine code to reach the maximum CPU power dissipation (thermal energy output for the central processing units).[73] Computer cooling apparatus are designed to dissipate power up to the thermal design power, rather than maximum power, and a power virus could cause the system to overheat if it does not have logic to stop the processor. This may cause permanent physical damage. Power viruses can be malicious, but are often suites of test software used for integration testing and thermal testing of computer components during the design phase of a product, or for product benchmarking.[74]

Stability test applications are similar programs which have the same effect as power viruses (high CPU usage) but stay under the user's control. They are used for testing CPUs, for example, when overclocking. Spinlock in a poorly written program may cause similar symptoms, if it lasts sufficiently long.

Different micro-architectures typically require different machine code to hit their maximum power. Examples of such machine code do not appear to be distributed in CPU reference materials.[75]

Infection vectors

[edit]As software is often designed with security features to prevent unauthorized use of system resources, many viruses must exploit and manipulate security bugs, which are software defects in a system or application software, to spread themselves and infect other computers. Software development strategies that produce large numbers of "bugs" will generally also produce potential exploitable "holes" or "entrances" for the virus.

To replicate itself, a virus must be permitted to execute code and write to memory. For this reason, many viruses attach themselves to executable files that may be part of legitimate programs (see code injection). If a user attempts to launch an infected program, the virus' code may be executed simultaneously.[76] In operating systems that use file extensions to determine program associations (such as Microsoft Windows), the extensions may be hidden from the user by default. This makes it possible to create a file that is of a different type than it appears to the user. For example, an executable may be created and named "picture.png.exe", in which the user sees only "picture.png" and therefore assumes that this file is a digital image and most likely is safe, yet when opened, it runs the executable on the client machine.[77] Viruses may be installed on removable media, such as flash drives. The drives may be left in a parking lot of a government building or other target, with the hopes that curious users will insert the drive into a computer. In a 2015 experiment, researchers at the University of Michigan found that 45–98 percent of users would plug in a flash drive of unknown origin.[78]

The vast majority of viruses target systems running Microsoft Windows. This is due to Microsoft's large market share of desktop computer users.[79] The diversity of software systems on a network limits the destructive potential of viruses and malware.[a] Open-source operating systems such as Linux allow users to choose from a variety of desktop environments, packaging tools, etc., which means that malicious code targeting any of these systems will only affect a subset of all users. Many Windows users are running the same set of applications, enabling viruses to rapidly spread among Microsoft Windows systems by targeting the same exploits on large numbers of hosts.[80][81][82][83]

While Linux and Unix in general have always natively prevented normal users from making changes to the operating system environment without permission, Windows users are generally not prevented from making these changes, meaning that viruses can easily gain control of the entire system on Windows hosts. This difference has continued partly due to the widespread use of administrator accounts in contemporary versions like Windows XP. In 1997, researchers created and released a virus for Linux—known as "Bliss".[84] Bliss, however, requires that the user run it explicitly, and it can only infect programs that the user has the access to modify. Unlike Windows users, most Unix users do not log in as an administrator, or "root user", except to install or configure software; as a result, even if a user ran the virus, it could not harm their operating system. The Bliss virus never became widespread, and remains chiefly a research curiosity. Its creator later posted the source code to Usenet, allowing researchers to see how it worked.[85]

Before computer networks became widespread, most viruses spread on removable media, particularly floppy disks. In the early days of the personal computer, many users regularly exchanged information and programs on floppies. Some viruses spread by infecting programs stored on these disks, while others installed themselves into the disk boot sector, ensuring that they would be run when the user booted the computer from the disk, usually inadvertently. Personal computers of the era would attempt to boot first from a floppy if one had been left in the drive. Until floppy disks fell out of use, this was the most successful infection strategy and boot sector viruses were the most common in the "wild" for many years. Traditional computer viruses emerged in the 1980s, driven by the spread of personal computers and the resultant increase in bulletin board system (BBS), modem use, and software sharing. Bulletin board–driven software sharing contributed directly to the spread of Trojan horse programs, and viruses were written to infect popularly traded software. Shareware and bootleg software were equally common vectors for viruses on BBSs.[86][87] Viruses can increase their chances of spreading to other computers by infecting files on a network file system or a file system that is accessed by other computers.[88]

Macro viruses have become common since the mid-1990s. Most of these viruses are written in the scripting languages for Microsoft programs such as Microsoft Word and Microsoft Excel and spread throughout Microsoft Office by infecting documents and spreadsheets. Since Word and Excel were also available for Mac OS, most could also spread to Macintosh computers. Although most of these viruses did not have the ability to send infected email messages, those viruses which did take advantage of the Microsoft Outlook Component Object Model (COM) interface.[89][90] Some old versions of Microsoft Word allow macros to replicate themselves with additional blank lines. If two macro viruses simultaneously infect a document, the combination of the two, if also self-replicating, can appear as a "mating" of the two and would likely be detected as a virus unique from the "parents".[91]

A virus may also send a web address link as an instant message to all the contacts (e.g., friends and colleagues' e-mail addresses) stored on an infected machine. If the recipient, thinking the link is from a friend (a trusted source) follows the link to the website, the virus hosted at the site may be able to infect this new computer and continue propagating.[92] Viruses that spread using cross-site scripting were first reported in 2002,[93] and were academically demonstrated in 2005.[94] There have been multiple instances of the cross-site scripting viruses in the "wild", exploiting websites such as MySpace (with the Samy worm) and Yahoo!.

Countermeasures

[edit]

In 1989 The ADAPSO Software Industry Division published Dealing With Electronic Vandalism,[95] in which they followed the risk of data loss by "the added risk of losing customer confidence."[96][97][98]

Many users install antivirus software that can detect and eliminate known viruses when the computer attempts to download or run the executable file (which may be distributed as an email attachment, or on USB flash drives, for example). Some antivirus software blocks known malicious websites that attempt to install malware. Antivirus software does not change the underlying capability of hosts to transmit viruses. Users must update their software regularly to patch security vulnerabilities ("holes"). Antivirus software also needs to be regularly updated to recognize the latest threats. This is because malicious hackers and other individuals are always creating new viruses. The German AV-TEST Institute publishes evaluations of antivirus software for Windows[99] and Android.[100]

Examples of Microsoft Windows anti virus and anti-malware software include the optional Microsoft Security Essentials[101] (for Windows XP, Vista and Windows 7) for real-time protection, the Windows Malicious Software Removal Tool[102] (now included with Windows (Security) Updates on "Patch Tuesday", the second Tuesday of each month), and Windows Defender (an optional download in the case of Windows XP).[103] Additionally, several capable antivirus software programs are available for free download from the Internet (usually restricted to non-commercial use).[104] Some such free programs are almost as good as commercial competitors.[105] Common security vulnerabilities are assigned CVE IDs and listed in the US National Vulnerability Database. Secunia PSI[106] is an example of software, free for personal use, that will check a PC for vulnerable out-of-date software, and attempt to update it. Ransomware and phishing scam alerts appear as press releases on the Internet Crime Complaint Center noticeboard. Ransomware is a virus that posts a message on the user's screen saying that the screen or system will remain locked or unusable until a ransom payment is made. Phishing is a deception in which the malicious individual pretends to be a friend, computer security expert, or other benevolent individual, with the goal of convincing the targeted individual to reveal passwords or other personal information.

Other commonly used preventive measures include timely operating system updates, software updates, careful Internet browsing (avoiding shady websites), and installation of only trusted software.[107] Certain browsers flag sites that have been reported to Google and that have been confirmed as hosting malware by Google.[108][109]

There are two common methods that an antivirus software application uses to detect viruses, as described in the antivirus software article. The first, and by far the most common method of virus detection is using a list of virus signature definitions. This works by examining the content of the computer's memory (its Random Access Memory (RAM), and boot sectors) and the files stored on fixed or removable drives (hard drives, floppy drives, or USB flash drives), and comparing those files against a database of known virus "signatures". Virus signatures are just strings of code that are used to identify individual viruses; for each virus, the antivirus designer tries to choose a unique signature string that will not be found in a legitimate program. Different antivirus programs use different "signatures" to identify viruses. The disadvantage of this detection method is that users are only protected from viruses that are detected by signatures in their most recent virus definition update, and not protected from new viruses (see "zero-day attack").[110]

A second method to find viruses is to use a heuristic algorithm based on common virus behaviors. This method can detect new viruses for which antivirus security firms have yet to define a "signature", but it also gives rise to more false positives than using signatures. False positives can be disruptive, especially in a commercial environment, because it may lead to a company instructing staff not to use the company computer system until IT services have checked the system for viruses. This can slow down productivity for regular workers.

Recovery strategies and methods

[edit]One may reduce the damage done by viruses by making regular backups of data (and the operating systems) on different media, that are either kept unconnected to the system (most of the time, as in a hard drive), read-only or not accessible for other reasons, such as using different file systems. This way, if data is lost through a virus, one can start again using the backup (which will hopefully be recent).[111] If a backup session on optical media like CD and DVD is closed, it becomes read-only and can no longer be affected by a virus (so long as a virus or infected file was not copied onto the CD/DVD). Likewise, an operating system on a bootable CD can be used to start the computer if the installed operating systems become unusable. Backups on removable media must be carefully inspected before restoration. The Gammima virus, for example, propagates via removable flash drives.[112][113]

Many websites run by antivirus software companies provide free online virus scanning, with limited "cleaning" facilities (after all, the purpose of the websites is to sell antivirus products and services). Some websites—like Google subsidiary VirusTotal.com—allow users to upload one or more suspicious files to be scanned and checked by one or more antivirus programs in one operation.[114][115] Additionally, several capable antivirus software programs are available for free download from the Internet (usually restricted to non-commercial use).[116] Microsoft offers an optional free antivirus utility called Microsoft Security Essentials, a Windows Malicious Software Removal Tool that is updated as part of the regular Windows update regime, and an older optional anti-malware (malware removal) tool Windows Defender that has been upgraded to an antivirus product in Windows 8.

Some viruses disable System Restore and other important Windows tools such as Task Manager and CMD. An example of a virus that does this is CiaDoor. Many such viruses can be removed by rebooting the computer, entering Windows "safe mode" with networking, and then using system tools or Microsoft Safety Scanner.[117] System Restore on Windows Me, Windows XP, Windows Vista and Windows 7 can restore the registry and critical system files to a previous checkpoint. Often a virus will cause a system to "hang" or "freeze", and a subsequent hard reboot will render a system restore point from the same day corrupted. Restore points from previous days should work, provided the virus is not designed to corrupt the restore files and does not exist in previous restore points.[118][119]

Microsoft's System File Checker (improved in Windows 7 and later) can be used to check for, and repair, corrupted system files.[120] Restoring an earlier "clean" (virus-free) copy of the entire partition from a cloned disk, a disk image, or a backup copy is one solution—restoring an earlier backup disk "image" is relatively simple to do, usually removes any malware, and may be faster than "disinfecting" the computer—or reinstalling and reconfiguring the operating system and programs from scratch, as described below, then restoring user preferences.[111] Reinstalling the operating system is another approach to virus removal. It may be possible to recover copies of essential user data by booting from a live CD, or connecting the hard drive to another computer and booting from the second computer's operating system, taking great care not to infect that computer by executing any infected programs on the original drive. The original hard drive can then be reformatted and the OS and all programs installed from original media. Once the system has been restored, precautions must be taken to avoid reinfection from any restored executable files.[121]

Popular culture

[edit]The first known description of a self-reproducing program in fiction is in the 1970 short story The Scarred Man by Gregory Benford which describes a computer program called VIRUS which, when installed on a computer with telephone modem dialing capability, randomly dials phone numbers until it hits a modem that is answered by another computer, and then attempts to program the answering computer with its own program, so that the second computer will also begin dialing random numbers, in search of yet another computer to program. The program rapidly spreads exponentially through susceptible computers and can only be countered by a second program called VACCINE.[122] His story was based on an actual computer virus written in FORTRAN that Benford had created and run on the lab computer in the 1960s, as a proof-of-concept, and which he told John Brunner about in 1970.[123]

The idea was explored further in two 1972 novels, When HARLIE Was One by David Gerrold and The Terminal Man by Michael Crichton, and became a major theme of the 1975 novel The Shockwave Rider by John Brunner.[124]

The 1973 Michael Crichton sci-fi film Westworld made an early mention of the concept of a computer virus, being a central plot theme that causes androids to run amok.[125][better source needed] Alan Oppenheimer's character summarizes the problem by stating that "...there's a clear pattern here which suggests an analogy to an infectious disease process, spreading from one...area to the next." To which the replies are stated: "Perhaps there are superficial similarities to disease" and, "I must confess I find it difficult to believe in a disease of machinery."[126]

In 2016, Jussi Parikka announced the creation of The Malware Museum of Art: a collection of malware programs, usually viruses, distributed in the 1980s and 1990s on home computers. Malware Museum of Art is hosted at The Internet Archive and is curated by Mikko Hyppönen from Helsinki, Finland.[127] The collection allows anyone with a computer to experience virus infection of decades ago with safety.[128]

Other malware

[edit]The term "virus" is also misused by extension to refer to other types of malware. "Malware" encompasses computer viruses along with many other forms of malicious software, such as computer "worms", ransomware, spyware, adware, trojan horses, keyloggers, rootkits, bootkits, malicious Browser Helper Object (BHOs), and other malicious software. The majority of active malware threats are trojan horse programs or computer worms rather than computer viruses. The term computer virus, coined by Fred Cohen in 1985, is a misnomer.[129] Viruses often perform some type of harmful activity on infected host computers, such as acquisition of hard disk space or central processing unit (CPU) time, accessing and stealing private information (e.g., credit card numbers, debit card numbers, phone numbers, names, email addresses, passwords, bank information, house addresses, etc.), corrupting data, displaying political, humorous or threatening messages on the user's screen, spamming their e-mail contacts, logging their keystrokes, or even rendering the computer useless. However, not all viruses carry a destructive "payload" and attempt to hide themselves—the defining characteristic of viruses is that they are self-replicating computer programs that modify other software without user consent by injecting themselves into the said programs, similar to a biological virus which replicates within living cells.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This is analogous to how genetic diversity in a population decreases the chance of a single disease wiping out a population in biology.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Internet comes down with a virus". The New York Times. August 6, 2014. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^

- Stallings, William (2012). Computer security : principles and practice. Boston: Pearson. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-13-277506-9.

- Avast n.d.

- ^ Piqueira, Jose R.C.; de Vasconcelos, Adolfo A.; Gabriel, Carlos E.C.J.; Araujo, Vanessa O. (2008). "Dynamic models for computer viruses". Computers & Security. 27 (7–8): 355–359. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2008.07.006. ISSN 0167-4048. Archived from the original on 2022-12-28. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ^

- Solomon 2011

- Aycock, John (2006). Computer Viruses and Malware. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-387-30236-2.

- ^ Avast n.d.

- ^ Yeo, Sang-Soo. (2012). Computer science and its applications : CSA 2012, Jeju, Korea, 22-25.11.2012. Springer. p. 515. ISBN 978-94-007-5699-1. OCLC 897634290.

- ^ Yu, Wei; Zhang, Nan; Fu, Xinwen; Zhao, Wei (October 2010). "Self-Disciplinary Worms and Countermeasures: Modeling and Analysis". IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems. 21 (10): 1501–1514. Bibcode:2010ITPDS..21.1501Y. doi:10.1109/tpds.2009.161. ISSN 1045-9219. S2CID 2242419.

- ^

- Filiol, Eric (2005). Computer viruses: from theory to applications. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-2-287-23939-7.

- Harley, David; et al. (2001). Viruses Revealed. McGraw-Hill. p. 6. ISBN 0-07-222818-0.

- Ludwig, Mark A. (1996). The Little Black Book of Computer Viruses: Volume 1, The Basic Technologies. American Eagle Publications. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-929408-02-0.

- Aycock, John (2006). Computer Viruses and Malware. Springer. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-387-30236-2.

- ^ Bell, David J.; et al., eds. (2004). "Virus". Cyberculture: The Key Concepts. Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 9780203647059.

- ^ a b "Viruses that can cost you". Archived from the original on 2013-09-25.

- ^ Granneman, Scott. "Linux vs. Windows Viruses". The Register. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ von Neumann, John (1966). "Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata" (PDF). Essays on Cellular Automata. University of Illinois Press: 66–87. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Éric Filiol, Computer viruses: from theory to applications, Volume 1 Archived 2017-01-14 at the Wayback Machine, Birkhäuser, 2005, pp. 19–38 ISBN 2-287-23939-1.

- ^ Risak, Veith (1972), "Selbstreproduzierende Automaten mit minimaler Informationsübertragung", Zeitschrift für Maschinenbau und Elektrotechnik, archived from the original on 2010-10-05

- ^ Kraus, Jürgen (February 1980), Selbstreproduktion bei Programmen (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-14, retrieved 2015-05-08

- ^ "Virus list". Archived from the original on 2006-10-16. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- ^ Chen, Thomas; Jean-Marc Robert (2004). "The Evolution of Viruses and Worms". Archived from the original on 2013-08-09. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ Parikka, Jussi (2007). Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses. New York: Peter Lang. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8204-8837-0. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- ^ "The Creeper Worm, the First Computer Virus". History of information. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 16 June 2022.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Russell, Deborah; Gangemi, G.T. (1991). Computer Security Basics. O'Reilly. p. 86. ISBN 0-937175-71-4.

- ^ a b Jesdanun, Anick (1 September 2007). "School prank starts 25 years of security woes". CNBC. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ Cohen, Fred (1984), Computer Viruses – Theory and Experiments, archived from the original on 2007-02-18

- ^ "Professor Len Adleman explains how he coined the term "computer virus"". www.welivesecurity.com. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ Cohen, Fred, An Undetectable Computer Virus, 1987, IBM

- ^ Burger, Ralph, 1991. Computer Viruses and Data Protection, pp. 19–20

- ^ Solomon, Alan; Gryaznov, Dmitry O. (1995). Dr. Solomon's Virus Encyclopedia. Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, U.K.: S & S International PLC. ISBN 1-897661-00-2.

- ^ Solomon 2011.

- ^ Gunn, J.B. (June 1984). "Use of virus functions to provide a virtual APL interpreter under user control". ACM SIGAPL APL Quote Quad. 14 (4). ACM New York, NY, USA: 163–168. doi:10.1145/384283.801093. ISSN 0163-6006.

- ^ "Boot sector virus repair". Antivirus.about.com. 2010-06-10. Archived from the original on 2011-01-12. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ "Amjad Farooq Alvi Inventor of first PC Virus post by Zagham". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2013-07-06. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ "winvir virus". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Miller, Greg (1996-02-20). "TECHNOLOGY : 'Boza' Infection of Windows 95 a Boon for Makers of Antivirus Software". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ Yoo, InSeon (29 October 2004). "Visualizing windows executable viruses using self-organizing maps". Proceedings of the 2004 ACM workshop on Visualization and data mining for computer security. pp. 82–89. doi:10.1145/1029208.1029222. ISBN 1-58113-974-8.

- ^ Grimes 2001, pp. 99-100.

- ^ "SCA virus". Virus Test Center, University of Hamburg. 1990-06-05. Archived from the original on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2014-01-14.

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (July 1988). "Dr. Pournelle vs. The Virus". BYTE. pp. 197–207. Retrieved 2025-04-12.

- ^ Ludwig 1998, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f Stallings, William (2012). Computer security : principles and practice. Boston: Pearson. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-13-277506-9.

- ^ Ludwig 1998, p. 292.

- ^ "Basic malware concepts" (PDF). cs.colostate.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-05-09. Retrieved 2016-04-25.

- ^ Gregory, Peter (2004). Computer viruses for dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Pub. p. 210. ISBN 0-7645-7418-3.

- ^ "Payload". encyclopedia.kaspersky.com. Archived from the original on 2023-12-06. Retrieved 2022-06-26.

- ^ "What is a malicious payload?". CloudFlare. Archived from the original on 2023-09-30. Retrieved 2022-06-26.

- ^ Szor, Peter (2005). The art of computer virus research and defense. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley. p. 43. ISBN 0-321-30454-3.

- ^ Serazzi, Giuseppe; Zanero, Stefano (2004). "Computer Virus Propagation Models" (PDF). In Calzarossa, Maria Carla; Gelenbe, Erol (eds.). Performance Tools and Applications to Networked Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2965. pp. 26–50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-08-18.

- ^ Avoine, Gildas (2007). Computer System Security: Basic Concepts and Solved Exercises. EPFL Press / CRC Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9781420046205. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- ^ Brain, Marshall; Fenton, Wesley (April 2000). "How Computer Viruses Work". HowStuffWorks.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^

- Polk, William T. (1995). Antivirus Tools and Techniques for Computer Systems. William Andrew (Elsevier). p. 4. ISBN 9780815513643. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- Salomon, David (2006). Foundations of Computer Security. Springer. pp. 47–48. ISBN 9781846283413. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- Grimes 2001, pp. 37-38

- ^ Grimes 2001, ch. 5.

- ^ Aycock, John (2006). Computer Viruses and Malware. Springer. p. 89. ISBN 9780387341880. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- ^ "What is boot sector virus?". Archived from the original on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- ^

- Skoudis, Edward (2004). "Infection mechanisms and targets". Malware: Fighting Malicious Code. Prentice Hall Professional. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9780131014053. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- Anonymous (2003). Maximum Security. Sams Publishing. pp. 331–333. ISBN 9780672324598. Archived from the original on 2014-07-06.

- ^ Mishra, Umakant (2012). "Detecting Boot Sector Viruses- Applying TRIZ to Improve Anti-Virus Programs". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1981886. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 109103460.

- ^ Jones, Dave (2001-12-01). "Building an e-mail virus detection system for your network". Linux Jourjal (92): 2. ISSN 1075-3583.

- ^ Béla G. Lipták, ed. (2002). Instrument engineers' handbook (3rd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 874. ISBN 9781439863442. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ "Computer Virus Strategies and Detection Methods" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ^ "What is Rootkit – Definition and Explanation". www.kaspersky.com. 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2022-06-26.

- ^ Kephart, J.O.; White, S.R. (1993). "Measuring and modeling computer virus prevalence". Proceedings 1993 IEEE Computer Society Symposium on Research in Security and Privacy. pp. 2–15. doi:10.1109/RISP.1993.287647. ISBN 0-8186-3370-0. S2CID 8436288.

- ^ Szor, Peter (2005). The Art of Computer Virus Research and Defense. Boston: Addison-Wesley. p. 285. ISBN 0-321-30454-3. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- ^ Fox-Brewster, Thomas. "Netflix Is Dumping Anti-Virus, Presages Death Of An Industry". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ "How Anti-Virus Software Works". Stanford University. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ "www.sans.org". Archived from the original on 2016-04-25. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ^ Jacobs, Stuart (2015-12-01). Engineering Information Security: The Application of Systems Engineering Concepts to Achieve Information Assurance. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119104711.

- ^ Bishop, Matt (2003). Computer Security: Art and Science. Addison-Wesley Professional. p. 620. ISBN 9780201440997. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- ^ a b Aycock, John (19 September 2006). Computer Viruses and Malware. Springer. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-387-34188-0. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017.

- ^ "What is a polymorphic virus? - Definition from WhatIs.com". SearchSecurity. Archived from the original on 2018-04-08. Retrieved 2018-08-07.

- ^ Kizza, Joseph M. (2009). Guide to Computer Network Security. Springer. p. 341. ISBN 9781848009165.

- ^ Eilam, Eldad (2011). Reversing: Secrets of Reverse Engineering. John Wiley & Sons. p. 216. ISBN 9781118079768. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- ^ "Virus Bulletin : Glossary – Polymorphic virus". Virusbtn.com. 2009-10-01. Archived from the original on 2010-10-01. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ Perriot, Fredrick; Peter Ferrie; Peter Szor (May 2002). "Striking Similarities" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- ^ "Virus Bulletin : Glossary — Metamorphic virus". Virusbtn.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-22. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ Kaspersky, Eugene (November 21, 2005). "The contemporary antivirus industry and its problems". SecureLight. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013.

- ^ Norinder, Ludvig (2013-12-03). "Breeding power-viruses for ARM devices". Archived from the original on 2024-03-24. Retrieved 2024-03-24.

- ^ Ganesan, Karthik; Jo, Jungho; Bircher, W. Lloyd; Kaseridis, Dimitris; Yu, Zhibin; John, Lizy K. (September 2010). "System-level max power (SYMPO)". Proceedings of the 19th international conference on Parallel architectures and compilation techniques - PACT '10. p. 19. doi:10.1145/1854273.1854282. ISBN 9781450301787. S2CID 6995371. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ "Thermal Performance Challenges from Silicon to Systems" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-09. Retrieved 2021-08-29.

- ^ "Virus Basics". US-CERT. Archived from the original on 2013-10-03.

- ^ "Virus Notice: Network Associates' AVERT Discovers First Virus That Can Infect JPEG Files, Assigns Low-Profiled Risk". Archived from the original on 2005-05-04. Retrieved 2002-06-13.

- ^ "Users Really Do Plug in USB Drives They Find" (PDF).

- ^ "Operating system market share". netmarketshare.com. Archived from the original on 2015-05-12. Retrieved 2015-05-16.

- ^ Mookhey, K.K.; et al. (2005). Linux: Security, Audit and Control Features. ISACA. p. 128. ISBN 9781893209787. Archived from the original on 2016-12-01.

- ^ Toxen, Bob (2003). Real World Linux Security: Intrusion Prevention, Detection, and Recovery. Prentice Hall Professional. p. 365. ISBN 9780130464569. Archived from the original on 2016-12-01.

- ^ Noyes, Katherine (Aug 3, 2010). "Why Linux Is More Secure Than Windows". PCWorld. Archived from the original on 2013-09-01.

- ^ Raggi, Emilio; et al. (2011). Beginning Ubuntu Linux. Apress. p. 148. ISBN 9781430236276. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- ^ "McAfee discovers first Linux virus" (Press release). McAfee, via Axel Boldt. 5 February 1997. Archived from the original on 17 December 2005.

- ^ Boldt, Axel (19 January 2000). "Bliss, a Linux 'virus'". Archived from the original on 14 December 2005.

- ^ Kim, David; Solomon, Michael G. (17 November 2010). Fundamentals of Information Systems Security. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 360–. ISBN 978-1-4496-7164-8. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017.

- ^ "1980s – Kaspersky IT Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- ^ "What is a Computer Virus?". Actlab.utexas.edu. 1996-03-31. Archived from the original on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ The Definitive Guide to Controlling Malware, Spyware, Phishing, and Spam. Realtimepublishers.com. 1 January 2005. pp. 48–. ISBN 978-1-931491-44-0. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017.

- ^ Cohen, Eli B. (2011). Navigating Information Challenges. Informing Science. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-1-932886-47-4. Archived from the original on 2017-12-19.

- ^ Bontchev, Vesselin. "Macro Virus Identification Problems". FRISK Software International. Archived from the original on 2012-08-05.

- ^ "Facebook 'photo virus' spreads via email". 2012-07-19. Archived from the original on 2014-05-29. Retrieved 2014-04-28.

- ^ Wever, Berend-Jan. "XSS bug in hotmail login page". Archived from the original on 2014-07-04. Retrieved 2014-04-07.

- ^ Alcorn, Wade. "The Cross-site Scripting Virus". bindshell.net. Archived from the original on 2014-08-23. Retrieved 2015-10-13.

- ^ Spafford, Eugene H.; Heaphy, Kathleen A.; Ferbrache, David J. (1989). Dealing With Electronic Vandalism. ADAPSO Software Industry Division.

- ^ "Ka-Boom: Anatomy of a Computer Virus". InformationWeek. December 3, 1990. p. 60.

- ^ "Trove". trove.nla.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ Hovav, Anat (August 2005). "Capital market reaction to defective IT products". Computers and Security. 24 (5): 409–424. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2005.02.003.

- ^ "Detailed test reports—(Windows) home user". AV-Test.org. Archived from the original on 2013-04-07. Retrieved 2013-04-08.

- ^ "Detailed test reports — Android mobile devices". AV-Test.org. 2019-10-22. Archived from the original on 2013-04-07.

- ^ "Microsoft Security Essentials". Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ "Malicious Software Removal Tool". Microsoft. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ "Windows Defender". Microsoft. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Rubenking, Neil J. (Feb 17, 2012). "The Best Free Antivirus for 2012". pcmag.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-14.

- ^ Rubenking, Neil J. (Jan 10, 2013). "The Best Antivirus for 2013". pcmag.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-14.

- ^ Rubenking, Neil J. "Secunia Personal Software Inspector 3.0 Review & Rating". PCMag.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-16. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- ^ "10 Step Guide to Protect Against Viruses". GrnLight.net. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Google Safe Browsing". Archived from the original on 2014-09-14.

- ^ "Report malicious software (URL) to Google". Archived from the original on 2014-09-12.

- ^ Zhang, Yu; et al. (2008). "A Novel Immune Based Approach For Detection of Windows PE Virus". In Tang, Changjie; et al. (eds.). Advanced Data Mining and Applications: 4th International Conference, ADMA 2008, Chengdu, China, October 8-10, 2008, Proceedings. Springer. p. 250. ISBN 9783540881919. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16.

- ^ a b "Good Security Habits | US-CERT". 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 2016-04-20. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ^ "W32.Gammima.AG". Symantec. Archived from the original on 2014-07-13. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ^ "Viruses! In! Space!". GrnLight.net. Archived from the original on 2014-05-24. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ^ "VirusTotal.com (a subsidiary of Google)". Archived from the original on 2012-06-16.

- ^ "VirScan.org". Archived from the original on 2013-01-26.

- ^ Rubenking, Neil J. (2014-04-23). "The Best Free Antivirus for 2014". pcmag.com. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12.

- ^ "Microsoft Safety Scanner". Archived from the original on 2013-06-29.

- ^ "Virus removal -Help". Archived from the original on 2015-01-31. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- ^ "W32.Gammima.AG Removal — Removing Help". Symantec. 2007-08-27. Archived from the original on 2014-08-04. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ^ "support.microsoft.com". Archived from the original on 2016-04-07. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ^ "www.us-cert.gov" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-19. Retrieved 2016-04-16.

- ^ Benford, Gregory (May 1970). "The Scarred Man". Venture Science Fiction. Vol. 4, no. 2. pp. 122–.

- ^ November 1999 "afterthoughts" to "The Scarred Man", Gregory Benford

- ^ Clute, John. "Brunner, John". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orion Publishing Group. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ IMDB synopsis of Westworld. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ^ Michael Crichton (November 21, 1973). Westworld (film). Tucson, Arizona: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Event occurs at 32 minutes.

And there's a clear pattern here which suggests an analogy to an infectious disease process, spreading from one resort area to the next." ... "Perhaps there are superficial similarities to disease." "I must confess I find it difficult to believe in a disease of machinery.

- ^ Parikka, Jussi (2016-02-19). "Computer viruses deserve a museum: they're an art form of their own". The Conversation. doi:10.64628/AB.hxtqpjjrc.

- ^ "The Malware Museum". Internet Archive. Retrieved 2025-09-21.

- ^ Ludwig 1998, p. 13.

- Grimes, Roger (2001). Malicious Mobile Code: Virus Protection for Windows. O'Reilly. ISBN 9781565926820.

- Ludwig, Mark (1998). The giant black book of computer viruses. Show Low, Ariz: American Eagle. ISBN 978-0-929408-23-1.

- Solomon, Alan (2011-06-14). "All About Viruses". VX Heavens. Archived from the original on 2012-01-17. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- "Worm vs. Virus: What's the Difference and Does It Matter?". Avast Academy. Avast Software s.r.o. n.d. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Burger, Ralf (16 February 2010) [1991]. Computer Viruses and Data Protection. Abacus. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-55755-123-8.

- Granneman, Scott (6 October 2003). "Linux vs. Windows Viruses". The Register. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Ludwig, Mark (1993). Computer Viruses, Artificial Life and Evolution. Tucson, Arizona: American Eagle Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-929408-07-1. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008.

- Mark Russinovich (November 2006). Advanced Malware Cleaning video (Web (WMV / MP4)). Microsoft Corporation. Archived from the original on 4 September 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- Parikka, Jussi (2007). Digital Contagions. A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses. Digital Formations. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-8837-0.

External links

[edit]- 'Computer Viruses – Theory and Experiments' – The original paper by Fred Cohen, 1984

- Hacking Away at the Counterculture by Andrew Ross (On hacking, 1990)

Computer virus

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A computer virus is a type of malicious software that attaches itself to legitimate programs or files, replicating by infecting other files or systems upon execution of the host.[13] This self-replication typically requires execution of the infected host, often involving user action, distinguishing it from worms that propagate independently without such intervention.[1] Essential attributes of a computer virus include its dependence on host files or programs for propagation, as it cannot spread independently like some network-based threats.[14] Additionally, viruses have the potential to alter, corrupt, or delete data on infected systems, though the primary mechanism is infection rather than immediate payload execution.[13] The term "computer virus" was first used in 1983 by Fred Cohen during his graduate research at the University of Southern California, who defined it as "a program that can 'infect' other programs by modifying them to include a possibly evolved copy of itself," and formalized this in his 1984 academic paper.[1] This definition established the foundational concept of viral self-replication in computing environments.[15]Key Characteristics

Computer viruses exhibit autonomy in replication, a core trait that enables them to spread without direct user intervention beyond the initial execution of an infected host. This process involves the virus embedding its code into other legitimate programs or files, where it remains dormant until the host is executed, at which point the viral code activates and seeks new targets for infection.[16] Unlike self-contained malware such as worms, viruses rely on this host-mediated propagation to achieve transitive spread across systems, leveraging user authorizations and sharing mechanisms to infect additional executables.[1] A defining feature of computer viruses is their host dependency, distinguishing them from independent executables by necessitating attachment to viable host files for survival and dissemination. Viruses typically integrate with executable formats like .exe files or document types such as .doc, modifying the host's structure—often by prepending, appending, or intruding into the code—while preserving the host's apparent functionality to avoid immediate detection.[12] This dependency ensures that the virus cannot operate standalone and instead propagates only when the infected host is run, exploiting the host's execution environment for replication.[17] Many computer viruses incorporate polymorphism and mutation techniques to obfuscate their signatures and evade antivirus detection. Polymorphic viruses encrypt or rearrange their code using variable keys or ciphers, generating unique variants each time they replicate while maintaining functional equivalence.[18] More advanced metamorphic variants go further by completely rewriting their entire codebase during propagation, replacing instructions with semantically identical alternatives to produce offspring that bear no structural resemblance to the parent.[19] Virus activation relies on sophisticated trigger mechanisms that determine when the malicious payload executes, allowing the virus to remain latent post-infection. These triggers can be time-based, such as activating on a specific date like the 13th of a month, or event-driven, responding to user actions like file access or system boot sequences.[17] Other common triggers include counters that delay payload delivery until a threshold number of infections occurs, or logical conditions tied to environmental factors, ensuring controlled and potentially stealthy operation.[12] The payload delivery phase represents the virus's non-replicative intent, executing harmful actions only after successful infection and trigger satisfaction to maximize impact while minimizing early exposure. Payloads often involve data corruption, such as overwriting files or scrambling disk sectors, or the installation of backdoors for unauthorized access.[12] These functions are designed by the virus author to achieve objectives ranging from disruption to espionage, with execution typically integrated into the host's runtime to blend seamlessly with normal operations.[17]Historical Development

Early Concepts and Origins

The concept of self-replicating programs in computing drew early inspiration from biological viruses, with theorists exploring how digital entities could mimic natural reproduction processes. In 1949, mathematician John von Neumann delivered lectures at the University of Illinois, outlining a theoretical framework for self-reproducing automata—hypothetical machines capable of creating exact copies of themselves within a cellular automaton environment.[20] This work, posthumously published as Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata in 1966, laid foundational ideas for programs that could propagate autonomously, influencing later discussions on computational replication without direct human intervention.[21] The first practical demonstration of such a self-replicating program emerged in 1971 with Bob Thomas's Creeper, an experimental worm developed at Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN) Technologies. Designed to test network mobility on the ARPANET, Creeper traversed Tenex operating systems across connected PDP-10 computers, copying itself to remote machines and displaying the benign message "I'm the creeper, catch me if you can!"[22] Unlike later malicious code, Creeper caused no harm and served purely as a proof-of-concept for self-propagation in a networked environment, prompting the creation of Ray Tomlinson's Reaper program to seek and eliminate it.[14] This experiment highlighted the potential for programs to spread uncontrollably across distributed systems, though it remained confined to research settings. Academic formalization of computer viruses occurred in 1983 through Fred Cohen's graduate work at the University of Southern California (USC). In his thesis experiments on VAX-11/780 systems running Unix, Cohen developed and demonstrated five viral programs that infected other executable files by appending malicious code, proving that such entities could evade traditional security measures without physical isolation.[15] Cohen's November 3 seminar presentation coined the term "computer virus" to describe a program capable of modifying others to include a copy of itself, emphasizing its infectious nature akin to biological pathogens.[16] His analysis concluded that viruses were theoretically uncontainable in open systems, a finding that shifted focus toward preventive strategies like access controls. Throughout these early developments, motivations were predominantly experimental and educational, aimed at understanding replication mechanics rather than causing disruption. Von Neumann's automata explored logical and informational reliability in complex systems, Creeper tested ARPANET resilience, and Cohen's viruses illustrated security vulnerabilities in controlled lab environments.[23] This non-malicious intent contrasted sharply with the destructive applications that would emerge later, establishing self-replication as a core concept in computer science while underscoring the need for safeguards against unintended spread.[24]Notable Incidents and Evolution

The first widespread personal computer virus, known as Brain, emerged in 1986 when brothers Basit and Amjad Farooq Alvi in Lahore, Pakistan, developed it to protect their medical software from piracy by infecting the boot sectors of MS-DOS floppy disks.[25] This boot sector virus marked the beginning of practical viral threats on IBM PC compatibles, spreading through shared disks and displaying a message with the brothers' contact information upon infection.[26] The late 1990s introduced the macro virus era, exemplified by Melissa in March 1999, which exploited Microsoft Word macros to propagate via email attachments and automatically forward itself to the first 50 contacts in the victim's Outlook address book.[27] Created by David L. Smith, Melissa rapidly overwhelmed corporate email servers worldwide, leading to temporary shutdowns at organizations like the Pentagon and causing an estimated $80 million in direct damages from lost productivity and cleanup efforts.[28] This incident highlighted the shift from physical media to network-based dissemination, accelerating the adoption of email security measures. Building on this momentum, the ILOVEYOU worm-virus hybrid struck in May 2000, spreading through deceptive email attachments disguised as love letters that executed Visual Basic scripts upon opening, overwriting files and emailing itself to all contacts in the Windows address book.[29] Attributed to Onel de Guzman in the Philippines, it infected tens of millions of computers globally within days, disrupting operations at major entities including the U.S. Senate and British Parliament, with estimated worldwide damages ranging from $6.7 billion to $15 billion due to system repairs, data loss, and downtime.[30] In the 2010s, computer viruses evolved toward fileless variants that evade traditional detection by operating in memory and registry without dropping executable files, as seen with Poweliks in 2014, which used JavaScript in Word documents to inject code into the Windows registry for persistence and ad-click fraud.[31] This approach represented a sophistication in stealth, exploiting legitimate system processes like rundll32.exe to avoid antivirus scans.[32] By the 2020s, polymorphic viruses have incorporated AI techniques, such as generative adversarial networks (GANs), to dynamically alter their code signatures and behaviors, enabling evasion of signature-based and even machine learning detectors.[33] These AI-assisted variants generate adversarial samples that mimic benign traffic or mutate in real-time, posing challenges to static analysis and contributing to a rise in sophisticated, targeted attacks up to 2025.[34] Over decades, virus propagation has transitioned from floppy disks in the 1980s to networked email and web vectors in the 1990s and 2000s, and further to mobile apps and Internet of Things (IoT) devices in the 2010s onward, where vulnerabilities in connected ecosystems like smart homes amplify spread.[35] Enhanced operating system protections, including built-in antivirus like Windows Defender and sandboxing in macOS and Android, have contributed to a decline in standalone viruses, shifting threats toward integrated malware ecosystems and ransomware hybrids.[36]Technical Design

Core Components

A typical computer virus is structured as a modular program consisting of distinct code segments that enable its survival and spread while minimizing detection. These components work in concert to allow the virus to integrate into host systems, propagate, execute harmful actions, and evade analysis. The design draws from early theoretical models, where viruses are defined as programs that modify other programs to include copies of themselves, often with additional functionality for persistence or disruption.[1] The infection routine is the initial code segment responsible for locating suitable host files and attaching the viral code to them. This routine typically scans for executable files or other targets, such as .exe files in Windows environments, and modifies their structure by appending or prepending the virus body. To perform these modifications, it often invokes operating system API calls, like CreateFile to open the target and WriteFile to overwrite or append data, ensuring the host remains functional while redirecting execution to the virus. Parasitic file-infecting viruses primarily employ two attachment methods: appending (tail parasitism) and prepending (head parasitism). In appending, the virus attaches its code to the end of the host file. To ensure execution of the virus code first, the virus modifies the host file's entry point—for example, by altering the AddressOfEntryPoint field in the Portable Executable (PE) header for Windows executables—to point to the start of the viral code. Alternatively, it may insert a jump instruction to the virus code at the original entry point. After performing its infection and payload operations, the virus jumps back to the original entry point, allowing the host program to continue normal execution. This method is more common because it avoids relocation issues, as the appended virus code does not require adjusting internal address references within the original host code. In prepending, the virus inserts its code at the beginning of the host file, shifting the original code to later positions in the file. Upon execution, the virus code runs first, completes its tasks, and then transfers control to the relocated original entry point. In complex formats like PE, this requires handling file headers, section alignments, and relocation tables to preserve executability, making the method more complicated and less common. Some prepending viruses use indirect techniques, such as copying the original program to a temporary file and executing it via system calls or batch scripts. These parasitic methods modify the file structure for covert infection while preserving the host program's normal execution, reducing the chance of immediate user detection.[37] The replication module handles the copying of the viral code to new hosts, incorporating logic to propagate efficiently without redundancy. This module executes during the infection process, duplicating the virus body and integrating it into the selected files or memory segments. A key feature is the inclusion of checks to avoid re-infecting the same file, such as scanning for a unique marker (e.g., a specific byte sequence) already embedded by prior infections, which prevents unnecessary resource consumption and reduces the risk of file corruption that could alert users. This selective replication ensures controlled spread, often limited to shared directories or networks accessible via user permissions.[1][38] The payload represents the core malicious or demonstrative functionality activated under specific conditions, distinguishing viruses from benign replicators. It may include actions like displaying innocuous messages for proof-of-concept viruses, encrypting files to demand ransom as in ransomware variants, or exfiltrating sensitive data to remote servers. For example, early experimental viruses demonstrated payloads such as infinite loops causing denial of service when a trigger like a date threshold (e.g., year > 1984) is met, while modern ones might delete system files or install backdoors. The payload's design prioritizes delayed execution to allow replication first, enhancing overall infectivity.[1][39][40] Anti-detection features comprise stealth techniques embedded in the virus to conceal its presence from scanners and users. Common methods include entry point obscuring (EPO), where the virus alters random instructions in the host file to insert a jump to its code, avoiding predictable modifications at the file's start that signature-based detectors target. Code obfuscation further hides the virus by encrypting its body, using polymorphic engines to mutate non-essential parts across infections, or employing metamorphic rewriting to generate unique variants that evade pattern matching. These mechanisms exploit the undecidability of precise virus detection, making static analysis challenging.[41][37][42] Many viruses incorporate an optional termination condition to control their lifecycle, such as triggers for dormancy or self-removal after achieving objectives. This might involve a time-based dormancy where the virus ceases replication upon reaching a predefined date or infection quota, reducing visibility during investigations. Self-removal routines can delete the viral code from hosts under certain conditions, like after payload delivery, to limit forensic traces, though precise implementation varies and often relies on the same API calls used for infection. Such features are not universal but appear in sophisticated designs to balance spread with evasion.[43][1]Operational Phases