Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rajputana

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2025) |

Rājputana (Hindi: [ɾaːdʒpʊt̪aːnaː]), meaning Land of the Rajputs,[1] was a historical region in the Indian subcontinent that included mainly the entire present-day Indian state of Rajasthan, parts of the neighboring states of Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat,[1] and adjoining areas of Sindh in modern-day southern Pakistan.[2] The region was known for its distinctive socio political structure, characterised by numerous Rajput kingdoms and principalities that maintained a strong warrior ethos and a deeply rooted tradition of honour, kinship, and martial governance.

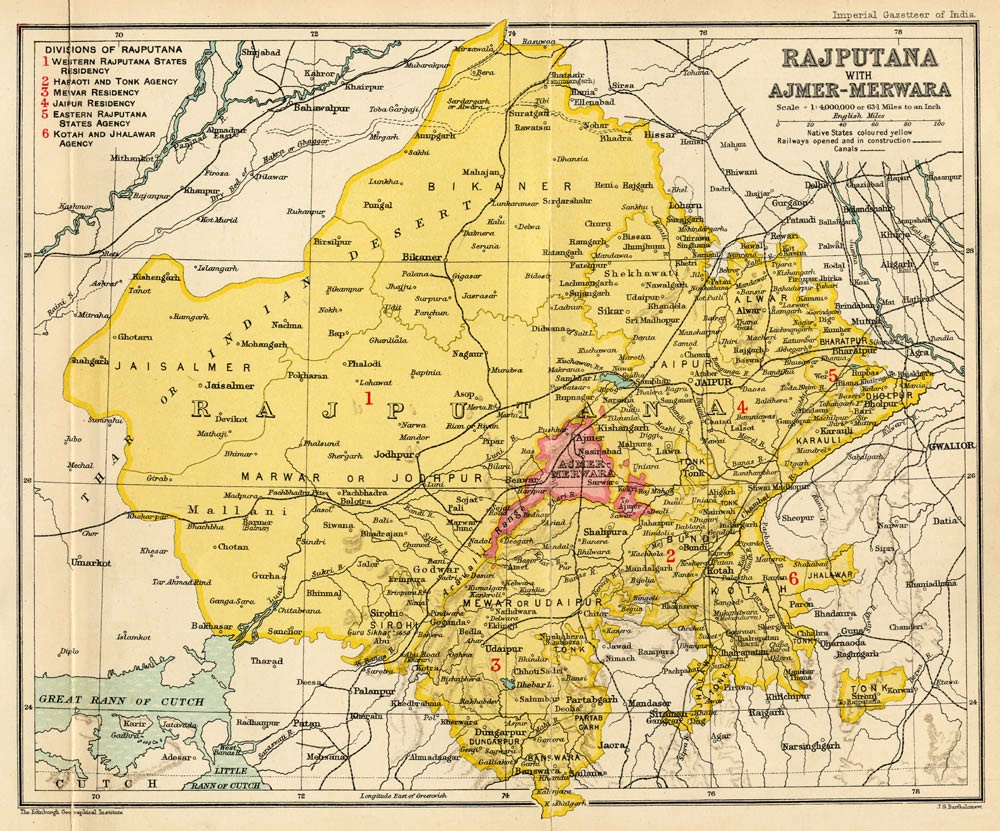

The main settlements to the west of the Aravalli Hills came to be known as Rajputana, early in the Medieval Period.[3] The name was later adopted by East India Company as the Rajputana Agency for its dependencies in the region of the present-day Indian state of Rājasthān.[4] The Rajputana Agency included 26 Rajput and 2 Jat princely states and two chiefships. This official term remained until its replacement by "Rajasthan" in the constitution of 1949.[4]

Name

[edit]George Thomas (Military Memories) was the first in 1800, to term this region the Rajputana Agency.[5] The historian John Keay in his book, India: A History, stated that the Rajputana name was coined by the British, but that the word achieved a retrospective authenticity: in an 1829 translation of Ferishta's history of early Islamic India, John Briggs discarded the phrase "Indian princes", as rendered in Dow's earlier version, and substituted "Rajpoot princes".

The region was previously long known as Gujratra (an early form of "Gujarat"), before it came to be called Rajputana during the medieval period, although the name "Gujratra" itself originated from the Gurjara-Pratiharas.[6][7]

Geography

[edit]The area of Rajputana is estimated to be 343,328 square km (132,559 square miles) and breaks down into two geographic divisions: [8]

- An area northwest of the Arāvalli Range including part of the Great Indian Thar Desert, with characteristics of being sandy and unproductive.

- A higher area southeast of the range, which is fertile by comparison.

The whole area forms the hill and plateau country between the north Indian plains and the main plateau of peninsular India. [9]

Transition to Rajasthan

[edit]The territory consisted of 23 states, one Sardari, one Jagir and the British district of Ajmer-Mewar. Most of the ruling princes were Rajputs. These were Rajput Kshatriyas from the historical region of Rajputana, who started entering the region in the seventh century. Jodhpur, Jaisalmer, Bikaner, Jaipur and Udaipur were the largest states. In 1947, integration of these states took place in various stages, as a result of which the State of Rajasthan came into existence. Some old areas of south-east Rajputana are now a part of Madhya Pradesh and some areas in the south-west are now part of Gujarat.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Rajputana". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Rajput". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Bose, Manilal (1998). Social Cultural History of Ancient India. Concept Publishing Company. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-702-2598-0.

- ^ a b R.K. Gupta; S.R. Bakshi (1 January 2008). Studies In Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages The Heritage Of Rajputana (Set Of 5 Vols.). Sarup & Sons. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-81-7625-841-8. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ F. K. Kapil (1999). Rajputana states, 1817-1950. Book Treasure. p. 1. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ John Keay (2001). India: a history. Grove Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

Colonel James Tod, who as the first British official to visit Rajasthan spent most of the 1820s exploring its political potential, formed a very different idea of "Rashboots".....and the whole region thenceforth became, for the British, 'Rajputana'. Historian R. C. Majumdar explained that the region was long known as Gurjaratra early form of Gujarat, before it came to be called Rajputana, early in the Muslim period.

- ^ R.C. Majumdar (1994). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 263. ISBN 8120804368.

- ^ "Rajputana". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Britannica Online. Retrieved 17 November 2025.

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series — Rajputana (PDF). Superintendent of Government Printing, Calcutta. 1908. p. 2. Retrieved 17 November 2025.

References

[edit]- Low, Sir Francis (ed.) The Indian Year Book & Who's Who 1945–46, The Times of India Press, Bombay.

- Sharma, Nidhi Transition from Feudalism to Democracy, Aalekh Publishers, Jaipur, 2000 ISBN 81-87359-06-4.

Rajputana

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Origin of the Name

The term "Rajputana" combines "Rajput," derived from the Sanskrit rājaputra meaning "son of a king," with the Persianate suffix -āna, signifying "land of" or "place of."[6][7] This etymological structure parallels designations like "Hindustana," reflecting a convention in Indo-Persian nomenclature for regional identifiers. Coined by British colonial administrators, the name first appeared in records around 1800, with George Thomas referring to the area as the "Rajputana Agency" in his Military Memories.[8] It served to administratively consolidate a patchwork of semi-independent princely states under indirect British oversight, rather than supplanting any pre-existing unified indigenous toponym. Indigenous references to the territory emphasized its political mosaic, employing state-specific appellations such as Marwar for the Jodhpur principality or Mewar for that of Udaipur, without a overarching regional label.[9] British surveys and gazetteers in the 19th century, including those by Colonel James Tod, formalized "Rajputana" to denote 18 principal and several minor Rajput-ruled states spanning modern-day Rajasthan.[8]Historical Usage and Alternatives

The term "Rajputana" entered widespread administrative usage by the British East India Company following the subsidiary alliance treaties concluded with key Rajput states between 1817 and 1818, after the defeat of Maratha power in the region during the Third Anglo-Maratha War.[10] These agreements, such as those with Jaipur in 1818 and Udaipur in 1818, placed the states under British protection while preserving nominal internal autonomy, leading to the categorization of the area as a distinct political entity under Company oversight.[10] The designation facilitated governance through a dedicated political agency, emphasizing the Rajput rulers' shared warrior ethos as a basis for collective administration rather than reflecting indigenous nomenclature.[11] British officer James Tod, serving as Political Agent to the Western Rajput States from 1818 to 1822, further entrenched the term through his seminal work Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, or the Central and Western Rajput States of India, published between 1829 and 1832.[12] Tod's detailed ethnographical and historical accounts, drawn from local bardic traditions and inscriptions, portrayed the region as a cohesive domain of Rajput principalities, thereby popularizing "Rajputana" in European scholarship and policy circles despite his subtitle's nod to "Rajasthan."[13] This usage persisted in official British documents and maps until the post-independence merger of the princely states into the United State of Rajasthan on March 30, 1949, marking the end of the colonial-era label.[14] Prior to British intervention, no evidence exists of "Rajputana" as a collective regional identifier in indigenous records or chronicles; instead, territories were denoted by individual polities or clan domains, such as Mewar under the Sisodias, Marwar under the Rathores, or Amber under the Kachwahas.[9] Rajput elites and chroniclers, including those compiling khyat and vamsavalis (genealogical texts), emphasized lineage-specific sovereignty and alliances over any overarching geographic unity, underscoring the term's character as a colonial construct imposed for bureaucratic convenience amid fragmented local realities.[9] In the early 20th century, Indian nationalists critiqued the British framing of "Rajputana" as divisive and advocated "Rajasthan"—meaning "land of kings"—to evoke a pan-Rajput cultural and historical continuum transcending princely boundaries and colonial classifications.[15] This shift aligned with broader independence-era efforts to foster regional integration, contrasting the administrative pragmatism of "Rajputana" with aspirations for a unified ethno-linguistic identity rooted in shared martial traditions and bardic lore.[16]Geography

Physical Landscape

Rajputana covers an area of 342,239 square kilometers, corresponding to the modern state of Rajasthan, and exhibits a varied topography shaped by ancient geological formations.[17] The Aravalli Range, extending approximately 670 kilometers in a southwest-to-northeast direction, bisects the region, separating the sandy, arid northwestern Thar Desert from the relatively fertile southeastern plains, including the Chambal River basin.[17] This range, among the oldest fold mountain systems globally, features average elevations of about 700 meters, with peaks providing natural barriers and defensive advantages that influenced historical settlement patterns.[18] Prominent hydrological features include the Sambhar Salt Lake, India's largest inland saltwater body at around 230 square kilometers during the monsoon season, and the Luni River, the region's primary westward-flowing waterway originating near Ajmer in the Aravallis and extending 495 kilometers before dissipating in the Rann of Kutch.[19][20] These seasonal rivers and saline lakes, often ephemeral due to the semi-arid plateaus, constrained water availability and favored fort construction on elevated, defensible sites such as the Chittorgarh hillfort, perched 180 meters above the surrounding Gambhiri and Berach river plains for strategic oversight and protection.[21] Historically, Rajputana's boundaries adjoined Gujarat to the southwest, Sindh (present-day Pakistan) to the west, Punjab to the north, and Malwa to the southeast, with the Aravallis and desert fringes limiting expansive urbanization in favor of fortified hill and plateau outposts.[22] The predominance of rugged terrains and low-rainfall plateaus further emphasized dispersed, defensible habitats over centralized large-scale development.[17]Climate and Natural Resources

Rajputana's climate is predominantly arid to semi-arid, marked by low and highly variable precipitation that averages 327 mm annually in western districts and 649 mm in eastern ones, with most rainfall occurring during the erratic southwest monsoon from June to September.[23] Extreme temperature fluctuations define the seasons, with summer maxima frequently surpassing 45°C and occasionally reaching 50°C in desert lowlands like those near Phalodi, while winter minima can fall below 0°C in elevated areas, accompanied by frost.[23] These conditions, characterized by prolonged dry spells and unreliable monsoons, have recurrently triggered droughts and famines, including severe events in 1747–48 and 1783–85 that caused mass livestock mortality and human migration due to crop failures.[24] Such environmental pressures historically favored pastoralism over intensive agriculture, fostering mobile herding practices and a culture emphasizing resource defense amid scarcity. The Aravalli Range hosts key mineral resources, including ancient zinc and copper deposits at sites like Zawar and Khetri, where mining evidence dates to at least 400 BCE through radiocarbon analysis of artifacts and smelting remains.[25] Sambhar Lake, an expansive inland saline body, has been a primary salt production center for over a millennium, with extraction methods yielding significant quantities by the 12th century under rulers like Prithviraj Chauhan and continuing as a staple resource into the colonial era.[26] Vegetation consists of sparse dry deciduous forests and scrublands, which supplied limited timber for constructing hill forts and palaces but were increasingly degraded by overgrazing from large herds and localized deforestation for fuel and expansion, accelerating soil erosion in vulnerable slopes.[27] These factors compounded aridity's effects, limiting biomass accumulation and contributing to desertification trends observed since medieval times.[28]Historical Origins

Emergence of Rajput Identity

The decline of the Gupta Empire around 550 CE created a power vacuum in northern India, leading to the fragmentation of centralized authority and the rise of local landowners, often termed thakurs, who consolidated control over agrarian territories through military service and land grants issued by residual imperial or regional rulers.[29] This process marked the emergence of a martial aristocracy that gradually coalesced into the Rajput class between the 6th and 12th centuries, characterized by claims to Kshatriya status and governance of semi-autonomous principalities. Epigraphic evidence, such as the Damodarpur copper-plate inscriptions from the reign of Kumaragupta III in 533 CE, records the term rājaputra (son of a king) applied to elite warriors, indicating an early terminological precursor to the later Rajput identity, though not yet denoting a distinct caste or ethnic group.[30] By the 7th century, inscriptions demonstrate the integration of diverse groups into this emerging class, with Gurjaras explicitly recognized as Kshatriyas or Rajputs within Hindu polity, as seen in records from the period that equate tribal or semi-tribal chieftains with royal lineages through grants of land and titles.[31] Copper-plate grants further reveal the assimilation of foreign-origin elements, including Huna invaders and Gurjara tribes, alongside indigenous agrarian communities, into Kshatriya varna via socio-political elevation rather than uniform ethnic descent; for instance, Huna remnants transitioned from tribal status to Rajput equivalents through alliances and feudal obligations.[29] [32] This process was pragmatic and evidence-based, driven by the need for military recruitment in fragmented polities, rather than primordial kinship ties. The Agnikula (fire-born) legend, positing the divine origin of clans like the Pratiharas, Chauhans, Paramaras, and Solankis from a sacrificial fire at Mount Abu, lacks support in pre-12th-century inscriptions and represents a later bardic invention by genealogists such as Bhats and Charans to fabricate unified Kshatriya pedigrees, possibly to obscure heterogeneous origins or legitimize rule amid Islamic incursions.[33] Contemporary sources prioritize verifiable land endowments and martial alliances over such myths, underscoring the Rajput identity's formation through empirical power consolidation rather than supernatural claims.[34]Early Clans and Migrations

The primary lineages of early Rajput clans, known as vanshas, were categorized into Suryavanshi (solar dynasty, claiming descent from Rama of the Ramayana epic) and Chandravanshi (lunar dynasty, tracing to Yadu or Krishna), with some groups like the Pratiharas associating with Agnivanshi (fire-born) origins via legendary rituals.[35][36] These genealogies, preserved in medieval texts such as the Kumarapala Prabandha (ca. 12th century), served to legitimize clan hierarchies amid feudal fragmentation, though modern analysis views them as constructed identities blending indigenous Kshatriya claims with pastoral or warrior group consolidations.[37] Medieval compilations, including the Varna Ratnakara (1324 CE) and bardic traditions, enumerate 36 principal clans, encompassing groups like the Rathores (Suryavanshi), Sisodias (Chandravanshi from Mewar branches), Chauhans, and Pratiharas, with alliances often pragmatic rather than rigidly genealogical.[37] Evidence from copper-plate grants and temple inscriptions, such as those from the 9th-10th centuries in Rajasthan and Gujarat, documents clan expansions through land endowments (agrahara systems) that rewarded military service, facilitating territorial holds in arid western India.[38] Migrations were driven by dynastic displacements and defensive needs following disruptions like the Arab incursion into Sindh in 712 CE under Muhammad bin Qasim, which spurred feudal consolidations to counter frontier threats without deeper penetration until later.[39] The Pratiharas, emerging as a clan around the 8th century possibly from southern or Gurjara stock, consolidated in Rajasthan and Malwa via such grants, checking Arab advances into Gujarat by the 9th century through decentralized warrior networks.[40] Similarly, Chauhan (Chahamana) groups shifted bases to Ajmer and Sambhar by the 10th century, as Pratihara overlords weakened post-tripartite struggles, evidenced by inscriptions like the Harsh Inscription (973 CE) marking their vassal-to-independent transitions.[41] Rathores, linked to Kannauj Gahadavala rulers, undertook westward movements by the 12th-13th centuries, establishing footholds in Marwar via kin-based migrations, as corroborated by dynastic charters tracing Siho (founder figure) to eastern lineages.[42] These patterns reflect causal responses to invasions and imperial declines, fostering clan-based feudalism over centralized states.[43]Medieval and Early Modern History

Rise of Rajput Kingdoms

The Sisodia dynasty of Mewar, with roots traceable to the 8th century, solidified its rule through territorial consolidation and defensive architecture, achieving prominence by the 15th century under Rana Kumbha (r. 1433–1468), who constructed 32 forts, including the expansive Kumbhalgarh complex featuring integrated water reservoirs for strategic sustenance.[44] [45] In Marwar, the Rathore clan established its foundational state in the 13th century, with Rao Siha seizing Pali around 1226 and initiating a pattern of incremental expansion amid the fragmented post-Gahadavala landscape of western Rajasthan.[46] [47] The Kachwaha rulers of Amber, governing from the 11th century onward, attained elevated status in the 16th century via pragmatic diplomacy, exemplified by Raja Bharmal's 1562 matrimonial alliance with Mughal emperor Akbar, which secured autonomy and resources for internal fortification and administration.[48] Governance achievements emphasized hydraulic engineering and cultural infrastructure to sustain arid economies; Rajput leaders developed extensive networks of irrigation tanks, canals, and stepwells, enabling land reclamation from desert fringes and boosting agricultural output in regions like Mewar and Marwar.[49] [50] Rana Kumbha's era marked a surge in temple construction, including the rebuilding of the Eklingji Shiva complex, which integrated devotional patronage with state legitimacy and architectural innovation blending indigenous styles.[51] These initiatives supported demographic expansion, as evidenced by increased settlement densities around fortified water systems that transformed marginal lands into productive territories. Persistent internal challenges, including succession disputes and clan fratricides, undermined cohesion; 15th-century Mewar witnessed intense rivalries following Kumbha's death, while broader Rajput polities grappled with hereditary conflicts that fragmented authority and diverted martial resources inward. Such dynamics, rooted in patrilineal inheritance customs, often protracted power vacuums, hindering sustained confederations despite shared warrior ethos.[52]Conflicts and Alliances with Islamic Powers

The Rajput kingdoms encountered significant military challenges from Islamic powers beginning in the late 12th century, exemplified by the Second Battle of Tarain on 8 March 1192, where Muhammad Ghori's forces decisively defeated Prithviraj Chauhan III of Ajmer through tactical feigned retreats and superior cavalry coordination, resulting in Chauhan's capture and execution, which facilitated Ghurid expansion into northern India.[53] This defeat fragmented Rajput confederacies but did not eradicate resistance; subsequent Rajput rulers, particularly in Mewar, inflicted heavy casualties on invaders, as evidenced by the prolonged defense of Chittorgarh, which withstood at least three major sieges by Delhi Sultanate and Mughal forces between 1303 and 1568, with defenders leveraging the fort's elevated terrain and water reservoirs to prolong engagements despite numerical disadvantages.[54] In the 16th century, Mughal emperor Akbar's campaigns highlighted both unyielding opposition and strategic accommodations. The third siege of Chittorgarh, initiated on 23 October 1567 and culminating in its capture on 23 February 1568 after four months of bombardment and mining operations, saw Mewar's Rajputs under Jaimal Rathore and Patta Sisodia repel initial assaults but ultimately succumb, leading to an estimated 30,000 civilian deaths ordered by Akbar post-victory and a mass jauhar involving thousands of Rajput women who self-immolated to evade enslavement, alongside a saka where surviving warriors charged to certain death.[54][55] These rituals, repeated in prior defeats like 1303 and 1535, underscored the demographic costs of resistance—potentially thousands lost per event—yet Rajput populations demonstrated resilience through clan reinforcements and migrations, maintaining martial capacity over generations.[56] Pragmatic alliances mitigated total subjugation for some clans; in 1562, Raja Bharmal of Amber (Kachwaha Rajputs) submitted to Akbar, securing a marriage alliance between his daughter Harkha Bai and the emperor, which integrated Amber into the Mughal mansabdari system—a rank-based hierarchy assigning military obligations (e.g., 5,000 zat for senior Rajput mansabdars) in exchange for jagir land grants and autonomy over internal affairs, enabling Amber's survival and expansion while providing Mughals with loyal cavalry contingents numbering up to 20,000 from Rajput recruits by the late 16th century.[48][57] This policy contrasted with Mewar's defiance under Rana Pratap, whose guerrilla tactics post-1576 Haldighati delayed full Mughal control, though alliances like Amber's supplied critical troops for Mughal campaigns elsewhere.[58] By the 17th century, under Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), renewed orthodoxy strained ties, prompting rebellions in Marwar and Mewar after interventions like the 1679 jizya reimposition and temple destructions, which alienated integrated Rajputs and fueled desertions. Aurangzeb's prolonged Deccan wars weakened central authority, and following his death in 1707, Rajput states exploited the vacuum, resisting Maratha chauth levies through coalitions—such as the 1708–1710 rebellion that extracted concessions from Mughal viceroys—while reclaiming territories amid Maratha incursions into Malwa and Gujarat, preserving de facto independence until British paramountcy.[59][60]Colonial Period

British Treaties and Rajputana Agency

Following the Third Anglo-Maratha War (1817–1818), which weakened Maratha power and intensified Pindari raids across northern India, the British East India Company pursued subsidiary alliances with Rajput states to secure their frontiers and neutralize potential threats. These alliances, rooted in stark military disparities—British forces having decisively defeated larger Maratha armies—compelled Rajput rulers to prioritize survival through British protection over autonomy in foreign affairs. In exchange for military aid against raiders and rivals, states ceded rights to conduct independent diplomacy, host foreign troops, or maintain armies beyond fixed limits, while often funding British garrisons via tribute or territorial cessions.[10][4] Key treaties solidified this shift: the Treaty of Jodhpur on 6 January 1818 with Maharaja Man Singh of Jodhpur, the Treaty of Udaipur on 13 January 1818 with Maharana Bhim Singh of Udaipur, and the Treaty of Jaipur in early 1818 with the Jaipur state. These pacts explicitly barred alliances with other powers, required British approval for successions and disputes, and established perpetual friendship, reflecting pragmatic acceptance of British paramountcy amid depleted local resources from prior conflicts. Jaipur and Jodhpur, for instance, relinquished claims to Ajmer and other districts to the British, further entrenching dependency.[10][61] The Rajputana Agency was formalized in 1832, headquartered at Ajmer, to centralize oversight of these relations under a British political agent subordinate to the Governor-General. It encompassed 18 gun-salute princely states—such as Jaipur, Jodhpur, Udaipur, and Bikaner—and around 10 smaller non-salute chiefships, enforcing treaty stipulations including fixed annual tributes deposited in British treasuries. This structure curtailed inter-state warfare through mandatory arbitration; the agent mediated feuds, imposed non-aggression, and deployed troops to enforce peace, transforming chronic Rajput rivalries into managed stability under British veto.[62][63] During the 1857 rebellion, the agency's framework proved pivotal: Rajputana states, bound by treaty oaths and reliant on British arbitration for internal order, largely withheld support from mutineers, supplying contingents and safe passage that preserved British hold on western India. Loyalty stemmed from self-interest—fear of anarchy without British mediation—rather than ideological alignment, averting the revolt's spread and reinforcing the alliances' utility in maintaining princely quiescence.[64][65]Administrative Changes under British Rule

The British administration in Rajputana, primarily through the Rajputana Agency established for oversight of princely states, introduced modifications to land revenue collection without directly supplanting local sovereignty. In directly administered territories like Ajmer-Merwara, the Mahalwari system was implemented, where revenue was assessed on village estates collectively, with periodic settlements revised every 20-30 years to reflect productivity changes. Princely states adopted similar British-influenced assessments post-1858, such as fixed cash revenues replacing variable crop shares, aiming to stabilize income amid fluctuating agriculture, though rulers retained assessment rights under paramountcy guidance.[66] Severe famines, notably the 1899-1900 drought affecting Rajputana and neighboring regions, resulted in approximately 1 million deaths, exposing vulnerabilities in arid-zone revenue systems dependent on rain-fed crops. This catastrophe prompted British-initiated famine codes and relief operations, alongside state-level irrigation expansions; for instance, Bikaner and Jodhpur rulers, with agency support, developed precursor canal works and tanks, laying groundwork for later large-scale projects like the Rajasthan Canal initiated in the 20th century. These interventions integrated Rajputana economically into British India via enhanced water management, yet preserved princely fiscal autonomy.[67][68] Modernization efforts included railway expansion, with the Rajputana State Railway's metre-gauge lines extending significantly by the early 1900s, connecting key states like Jaipur and Udaipur to broader networks by 1905, facilitating trade in grains and cotton while subjecting local economies to imperial market fluctuations. Concurrently, decennial censuses from 1871 onward systematically enumerated populations, codifying Rajput clans through ethnographic classifications that fixed fluid identities into administrative categories for recruitment and governance. Princely courts maintained customary laws, but British political agents influenced succession and disputes, curbing historical inter-clan raids that had characterized pre-paramountcy feuds.[69] British paramountcy effectively quelled endemic lawlessness, such as feudal levies and border skirmishes, by enforcing non-aggression pacts, yet this stabilization reinforced hierarchical feudal structures, as princes gained leverage over thakurs (nobles) with agency backing, thereby postponing internal reforms toward representative governance until post-independence. Revenue data from agency reports indicate economic incorporation—e.g., Rajputana's land revenue rising from £1.2 million in 1880 to £1.8 million by 1910—without eroding core sovereign prerogatives, illustrating indirect rule's dual legacy of order and stasis.[4]Political Structure

Composition of Princely States

The Rajputana Agency administered 18 principal princely states and 2 estates, covering 127,541 square miles, along with numerous smaller chiefships and hereditary thikanas functioning as sub-feudatories by 1901.[70] These entities formed a hierarchical structure where larger states held greater autonomy and prestige, while thikanas owed allegiance to overlords, maintaining feudal ties.[11] Rajput clans dominated the rulership, with key states including Udaipur under the Sisodias, Jodhpur under the Rathores, Jaipur under the Kachwahas, Bikaner under the Rathores, and Kota under the Hada Chauhans, reflecting the martial and genealogical prominence of Rajput lineages in the region.[11] Non-Rajput inclusions comprised Tonk, ruled by Muslim Nawabs of Pathan origin, and Bharatpur and Dholpur, governed by Jat rulers, highlighting ethnic diversity amid overall Rajput majority.[11] By 1900, the total number of polities approached 26 when accounting for minor chiefships like those in Sirohi and Shahpura.[11] Status and hierarchy were formalized through the British gun salute system, which denoted a ruler's precedence and influenced post-1947 privy purses proportional to salute level and state revenue.[71] Udaipur received the highest 19-gun salute, Jodhpur, Jaipur, Bikaner, and Kota 17 guns, Alwar 15 guns, and smaller states like Bundi and Kishangarh 9 to 11 guns, embedding a clear pecking order among the states.[71]| State | Ruling Clan/Ethnicity | Gun Salute |

|---|---|---|

| Udaipur | Sisodia Rajput | 19 |

| Jodhpur | Rathore Rajput | 17 |

| Jaipur | Kachwaha Rajput | 17 |

| Bikaner | Rathore Rajput | 17 |

| Kota | Hada Chauhan Rajput | 17 |

| Alwar | Kachwaha Rajput | 15 |

| Tonk | Pathan Muslim | 11 |

| Bharatpur | Jat | 17 (local) |

| Bundi | Hada Chauhan Rajput | 17 (local) |