Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Process (anatomy).

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Process (anatomy)

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Process | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | processus |

| TA98 | A02.0.00.028 |

| TA2 | 397 |

| FMA | 75428 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

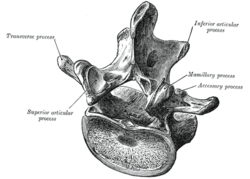

In anatomy, a process (Latin: processus) is a projection or outgrowth of tissue from a larger body.[1] For instance, in a vertebra, a process may serve for muscle attachment and leverage (as in the case of the transverse and spinous processes), or to fit (forming a synovial joint), with another vertebra (as in the case of the articular processes).[2] The word is also used at the microanatomic level, where cells can have processes such as cilia or pedicels. Depending on the tissue, processes may also be called by other terms, such as apophysis, tubercle, or protuberance.

Examples

[edit]Examples of processes include:

- The many processes of the human skull:

- The mastoid and styloid processes of the temporal bone

- The zygomatic process of the temporal bone

- The zygomatic process of the frontal bone

- The orbital, temporal, lateral, frontal, and maxillary processes of the zygomatic bone

- The anterior, middle, and posterior clinoid processes and the petrosal process of the sphenoid bone

- The uncinate process of the ethmoid bone

- The jugular process of the occipital bone

- The alveolar, frontal, zygomatic, and palatine processes of the maxilla

- The ethmoidal and maxillary processes of the inferior nasal concha

- The pyramidal, orbital, and sphenoidal processes of the palatine bone

- The coronoid and condyloid processes of the mandible

- The xiphoid process at the end of the sternum

- The acromion and coracoid processes of the scapula

- The coronoid process of the ulna

- The radial and ulnar styloid processes

- The uncinate processes of ribs found in birds and reptiles

- The uncinate process of the pancreas

- The spinous, articular, transverse, accessory, uncinate, and mammillary processes of the vertebrae

- The trochlear process of the heel

- The appendix, which is sometimes called the "vermiform process", notably in Gray's Anatomy

- The olecranon process of the ulna

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Process (anatomy)

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

In anatomy, a process (Latin: processus) is a projection or outgrowth of tissue from a larger body structure.[1] Bony processes are a common type, referring to projections or prominences extending from the surface of a bone, typically serving as attachment sites for muscles, ligaments, tendons, or contributing to the formation of joints.[2] These bony structures vary in shape, size, and function, arising during embryonic development through ossification processes influenced by genetic factors and mechanical stresses.[2] They are essential for skeletal stability, locomotion, and overall body support, with their prominence often adapted to specific biomechanical demands.[3] The term also applies to soft tissue and cellular processes, such as outgrowths in organs or neuronal extensions, as detailed in later sections.

Common types of bony processes include the spinous process, a sharp, raised elevation found on vertebrae for muscle attachment and spinal articulation; the transverse process, a laterally projecting feature on vertebrae that anchors muscles and ligaments involved in torso movement; and the styloid process, a slender, pointed projection such as the one on the temporal bone that supports nearby muscles and ligaments.[2] Other notable examples encompass the acromial process of the scapula, which forms part of the shoulder joint by articulating with the clavicle, and the coracoid process, a beak-like hook on the scapula serving as an attachment for the pectoralis minor muscle and other structures.[2] These markings are classified under broader bone surface features, distinguishing them from depressions like fossae or foramina, and their study is fundamental to understanding skeletal morphology and pathology.[3]