Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Protein superfamily

View on WikipediaA protein superfamily is the largest grouping (clade) of proteins for which common ancestry can be inferred (see homology). Usually this common ancestry is inferred from structural alignment[1] and mechanistic similarity, even if no sequence similarity is evident.[2] Sequence homology can then be deduced even if not apparent (due to low sequence similarity). Superfamilies typically contain several protein families which show sequence similarity within each family. The term protein clan is commonly used for protease and glycosyl hydrolases superfamilies based on the MEROPS and CAZy classification systems.[2][3]

Identification

[edit]Superfamilies of proteins are identified using a number of methods. Closely related members can be identified by different methods to those needed to group the most evolutionarily divergent members.

Sequence similarity

[edit]

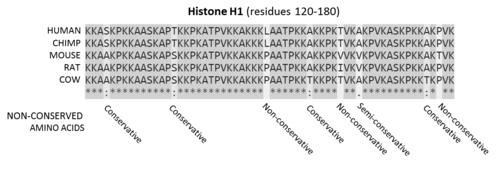

- * conserved sequence,

- : conservative mutations,

- . semi-conservative mutations, and

- ␣ non-conservative mutations.

Historically, the similarity of different amino acid sequences has been the most common method of inferring homology.[5] Sequence similarity is considered a good predictor of relatedness, since similar sequences are more likely the result of gene duplication and divergent evolution, rather than the result of convergent evolution. Amino acid sequence is typically more conserved than DNA sequence (due to the degenerate genetic code), so it is a more sensitive detection method. Since some of the amino acids have similar properties (e.g., charge, hydrophobicity, size), conservative mutations that interchange them are often neutral to function. The most conserved sequence regions of a protein often correspond to functionally important regions like catalytic sites and binding sites, since these regions are less tolerant to sequence changes.

Using sequence similarity to infer homology has several limitations. There is no minimum level of sequence similarity guaranteed to produce identical structures. Over long periods of evolution, related proteins may show no detectable sequence similarity to one another. Sequences with many insertions and deletions can also sometimes be difficult to align and so identify the homologous sequence regions. In the PA clan of proteases, for example, not a single residue is conserved through the superfamily, not even those in the catalytic triad. Conversely, the individual families that make up a superfamily are defined on the basis of their sequence alignment, for example the C04 protease family within the PA clan.

Nevertheless, sequence similarity is the most commonly used form of evidence to infer relatedness, since the number of known sequences vastly outnumbers the number of known tertiary structures.[6] In the absence of structural information, sequence similarity constrains the limits of which proteins can be assigned to a superfamily.[6]

Structural similarity

[edit]

Structure is much more evolutionarily conserved than sequence, such that proteins with highly similar structures can have entirely different sequences.[7] Over very long evolutionary timescales, very few residues show detectable amino acid sequence conservation, however secondary structural elements and tertiary structural motifs are highly conserved. Some protein dynamics[8] and conformational changes of the protein structure may also be conserved, as is seen in the serpin superfamily.[9] Consequently, protein tertiary structure can be used to detect homology between proteins even when no evidence of relatedness remains in their sequences. Structural alignment programs, such as DALI, use the 3D structure of a protein of interest to find proteins with similar folds.[10] However, on rare occasions, related proteins may evolve to be structurally dissimilar[11] and relatedness can only be inferred by other methods.[12][13][14]

Mechanistic similarity

[edit]The catalytic mechanism of enzymes within a superfamily is commonly conserved, although substrate specificity may be significantly different.[15] Catalytic residues also tend to occur in the same order in the protein sequence.[16] For the families within the PA clan of proteases, although there has been divergent evolution of the catalytic triad residues used to perform catalysis, all members use a similar mechanism to perform covalent, nucleophilic catalysis on proteins, peptides or amino acids.[17] However, mechanism alone is not sufficient to infer relatedness. Some catalytic mechanisms have been convergently evolved multiple times independently, and so form separate superfamilies,[18][19][20] and in some superfamilies display a range of different (though often chemically similar) mechanisms.[15][21]

Evolutionary significance

[edit]Protein superfamilies represent the current limits of our ability to identify common ancestry.[22] They are the largest evolutionary grouping based on direct evidence that is currently possible. They are therefore amongst the most ancient evolutionary events currently studied. Some superfamilies have members present in all kingdoms of life, indicating that the last common ancestor of that superfamily was in the last universal common ancestor of all life (LUCA).[23]

Superfamily members may be in different species, with the ancestral protein being the form of the protein that existed in the ancestral species (orthology). Conversely, the proteins may be in the same species, but evolved from a single protein whose gene was duplicated in the genome (paralogy).

Diversification

[edit]A majority of proteins contain multiple domains. Between 66 and 80% of eukaryotic proteins have multiple domains while about 40-60% of prokaryotic proteins have multiple domains.[5] Over time, many of the superfamilies of domains have mixed together. In fact, it is very rare to find "consistently isolated superfamilies".[5][1] When domains do combine, the N- to C-terminal domain order (the "domain architecture") is typically well conserved. Additionally, the number of domain combinations seen in nature is small compared to the number of possibilities, suggesting that selection acts on all combinations.[5]

Examples

[edit]- α/β hydrolase superfamily

- Members share an α/β sheet, containing 8 strands connected by helices, with catalytic triad residues in the same order,[24] activities include proteases, lipases, peroxidases, esterases, epoxide hydrolases and dehalogenases.[25]

- Alkaline phosphatase superfamily

- Members share an αβα sandwich structure[26] as well as performing common promiscuous reactions by a common mechanism.[27]

- Globin superfamily

- Members share an 8-alpha helix globular globin fold.[28][29]

- Immunoglobulin superfamily

- Members share a sandwich-like structure of two sheets of antiparallel β strands (Ig-fold), and are involved in recognition, binding, and adhesion.[30][31]

- LYRM superfamily

- Members share a conserved LYR motif (leucine–tyrosine–arginine) embedded within a three α‑helix structure and function as adaptor proteins essential for mitochondrial Fe–S cluster assembly and oxidative phosphorylation complex assembly.[32][33]

- PA clan

- Members share a chymotrypsin-like double β-barrel fold and similar proteolysis mechanisms but sequence identity of <10%. The clan contains both cysteine and serine proteases (different nucleophiles).[2][34]

- Ras superfamily

- Members share a common catalytic G domain of a 6-strand β sheet surrounded by 5 α-helices.[35]

- RSH superfamily

- Members share capability to hydrolyze and/or synthesize ppGpp alarmones in the stringent response.[36]

- Serpin superfamily

- Members share a high-energy, stressed fold which can undergo a large conformational change, which is typically used to inhibit serine and cysteine proteases by disrupting their structure.[9]

- TIM barrel superfamily

- Members share a large α8β8 barrel structure. It is one of the most common protein folds and the monophylicity of this superfamily is still contested.[37][38]

Protein superfamily resources

[edit]Several biological databases document protein superfamilies and protein folds, for example:

- Pfam - Protein families database of alignments and HMMs

- PROSITE - Database of protein domains, families and functional sites

- PIRSF - SuperFamily Classification System

- PASS2 - Protein Alignment as Structural Superfamilies v2

- SUPERFAMILY - Library of HMMs representing superfamilies and database of (superfamily and family) annotations for all completely sequenced organisms

- SCOP and CATH - Classifications of protein structures into superfamilies, families and domains

Similarly there are algorithms that search the PDB for proteins with structural homology to a target structure, for example:

- DALI - Structural alignment based on a distance alignment matrix method

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Holm L, Rosenström P (July 2010). "Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D". Nucleic Acids Research. 38 (Web Server issue): W545–9. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq366. PMC 2896194. PMID 20457744.

- ^ a b c Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A (January 2012). "MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors". Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (Database issue): D343–50. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr987. PMC 3245014. PMID 22086950.

- ^ Henrissat B, Bairoch A (June 1996). "Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases". The Biochemical Journal. 316 (Pt 2): 695–6. doi:10.1042/bj3160695. PMC 1217404. PMID 8687420.

- ^ "Clustal FAQ #Symbols". Clustal. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d Han JH, Batey S, Nickson AA, Teichmann SA, Clarke J (April 2007). "The folding and evolution of multidomain proteins". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 8 (4): 319–30. doi:10.1038/nrm2144. PMID 17356578. S2CID 13762291.

- ^ a b Pandit SB, Gosar D, Abhiman S, Sujatha S, Dixit SS, Mhatre NS, Sowdhamini R, Srinivasan N (January 2002). "SUPFAM--a database of potential protein superfamily relationships derived by comparing sequence-based and structure-based families: implications for structural genomics and function annotation in genomes". Nucleic Acids Research. 30 (1): 289–93. doi:10.1093/nar/30.1.289. PMC 99061. PMID 11752317.

- ^ Orengo CA, Thornton JM (2005). "Protein families and their evolution-a structural perspective". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 74 (1): 867–900. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133029. PMID 15954844.

- ^ Liu Y, Bahar I (September 2012). "Sequence evolution correlates with structural dynamics". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (9): 2253–63. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss097. PMC 3424413. PMID 22427707.

- ^ a b Silverman GA, Bird PI, Carrell RW, Church FC, Coughlin PB, Gettins PG, Irving JA, Lomas DA, Luke CJ, Moyer RW, Pemberton PA, Remold-O'Donnell E, Salvesen GS, Travis J, Whisstock JC (September 2001). "The serpins are an expanding superfamily of structurally similar but functionally diverse proteins. Evolution, mechanism of inhibition, novel functions, and a revised nomenclature". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (36): 33293–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.R100016200. PMID 11435447.

- ^ Holm L, Laakso LM (July 2016). "Dali server update". Nucleic Acids Research. 44 (W1): W351–5. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw357. PMC 4987910. PMID 27131377.

- ^ Pascual-García A, Abia D, Ortiz ÁR, Bastolla U (2009). "Cross-Over between Discrete and Continuous Protein Structure Space: Insights into Automatic Classification and Networks of Protein Structures". PLOS Computational Biology. 5 (3) e1000331. Bibcode:2009PLSCB...5E0331P. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000331. PMC 2654728. PMID 19325884.

- ^ Li D, Zhang L, Yin H, Xu H, Satkoski Trask J, Smith DG, Li Y, Yang M, Zhu Q (June 2014). "Evolution of primate α and θ defensins revealed by analysis of genomes". Molecular Biology Reports. 41 (6): 3859–66. doi:10.1007/s11033-014-3253-z. PMID 24557891. S2CID 14936647.

- ^ Krishna SS, Grishin NV (April 2005). "Structural drift: a possible path to protein fold change". Bioinformatics. 21 (8): 1308–10. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti227. PMID 15604105.

- ^ Bryan PN, Orban J (August 2010). "Proteins that switch folds". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 20 (4): 482–8. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2010.06.002. PMC 2928869. PMID 20591649.

- ^ a b Dessailly, Benoit H.; Dawson, Natalie L.; Das, Sayoni; Orengo, Christine A. (2017), "Function Diversity within Folds and Superfamilies", From Protein Structure to Function with Bioinformatics, Springer Netherlands, pp. 295–325, doi:10.1007/978-94-024-1069-3_9, ISBN 978-94-024-1067-9

- ^ Echave J, Spielman SJ, Wilke CO (February 2016). "Causes of evolutionary rate variation among protein sites". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 17 (2): 109–21. doi:10.1038/nrg.2015.18. PMC 4724262. PMID 26781812.

- ^ Shafee T, Gatti-Lafranconi P, Minter R, Hollfelder F (September 2015). "Handicap-Recover Evolution Leads to a Chemically Versatile, Nucleophile-Permissive Protease". ChemBioChem. 16 (13): 1866–1869. doi:10.1002/cbic.201500295. PMC 4576821. PMID 26097079.

- ^ Buller AR, Townsend CA (February 2013). "Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (8): E653–61. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110E.653B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221050110. PMC 3581919. PMID 23382230.

- ^ Coutinho PM, Deleury E, Davies GJ, Henrissat B (April 2003). "An evolving hierarchical family classification for glycosyltransferases". Journal of Molecular Biology. 328 (2): 307–17. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00307-3. PMID 12691742.

- ^ Zámocký M, Hofbauer S, Schaffner I, Gasselhuber B, Nicolussi A, Soudi M, Pirker KF, Furtmüller PG, Obinger C (May 2015). "Independent evolution of four heme peroxidase superfamilies". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 574: 108–19. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.025. PMC 4420034. PMID 25575902.

- ^ Akiva, Eyal; Brown, Shoshana; Almonacid, Daniel E.; Barber, Alan E.; Custer, Ashley F.; Hicks, Michael A.; Huang, Conrad C.; Lauck, Florian; Mashiyama, Susan T. (2013-11-23). "The Structure–Function Linkage Database". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (D1): D521 – D530. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1130. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 3965090. PMID 24271399.

- ^ Shakhnovich BE, Deeds E, Delisi C, Shakhnovich E (March 2005). "Protein structure and evolutionary history determine sequence space topology". Genome Research. 15 (3): 385–92. arXiv:q-bio/0404040. doi:10.1101/gr.3133605. PMC 551565. PMID 15741509.

- ^ Ranea JA, Sillero A, Thornton JM, Orengo CA (October 2006). "Protein superfamily evolution and the last universal common ancestor (LUCA)". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 63 (4): 513–25. Bibcode:2006JMolE..63..513R. doi:10.1007/s00239-005-0289-7. hdl:10261/78338. PMID 17021929. S2CID 25258028.

- ^ Carr PD, Ollis DL (2009). "Alpha/beta hydrolase fold: an update". Protein and Peptide Letters. 16 (10): 1137–48. doi:10.2174/092986609789071298. PMID 19508187.

- ^ Nardini M, Dijkstra BW (December 1999). "Alpha/beta hydrolase fold enzymes: the family keeps growing". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 9 (6): 732–7. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(99)00037-8. PMID 10607665.

- ^ "SCOP". Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Mohamed MF, Hollfelder F (January 2013). "Efficient, crosswise catalytic promiscuity among enzymes that catalyze phosphoryl transfer". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1834 (1): 417–24. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.07.015. PMID 22885024.

- ^ Branden C, Tooze J (1999). Introduction to protein structure (2nd ed.). New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 978-0-8153-2305-1.

- ^ Bolognesi M, Onesti S, Gatti G, Coda A, Ascenzi P, Brunori M (February 1989). "Aplysia limacina myoglobin. Crystallographic analysis at 1.6 A resolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 205 (3): 529–44. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(89)90224-6. PMID 2926816.

- ^ Bork P, Holm L, Sander C (September 1994). "The immunoglobulin fold. Structural classification, sequence patterns and common core". Journal of Molecular Biology. 242 (4): 309–20. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1582. PMID 7932691.

- ^ Brümmendorf T, Rathjen FG (1995). "Cell adhesion molecules 1: immunoglobulin superfamily". Protein Profile. 2 (9): 963–1108. PMID 8574878.

- ^ Angerer, Heike (2015-02-12). "Eukaryotic LYR Proteins Interact with Mitochondrial Protein Complexes". Biology. 4 (1): 133–150. doi:10.3390/biology4010133. ISSN 2079-7737. PMC 4381221. PMID 25686363.

- ^ Dohnálek, Vít; Doležal, Pavel (May 2024). "Installation of LYRM proteins in early eukaryotes to regulate the metabolic capacity of the emerging mitochondrion". Open Biology. 14 (5). doi:10.1098/rsob.240021. ISSN 2046-2441. PMC 11293456. PMID 38772414.

- ^ Bazan JF, Fletterick RJ (November 1988). "Viral cysteine proteases are homologous to the trypsin-like family of serine proteases: structural and functional implications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 85 (21): 7872–6. Bibcode:1988PNAS...85.7872B. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.21.7872. PMC 282299. PMID 3186696.

- ^ Vetter IR, Wittinghofer A (November 2001). "The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions". Science. 294 (5545): 1299–304. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.1299V. doi:10.1126/science.1062023. PMID 11701921. S2CID 6636339.

- ^ Atkinson, Gemma C.; Tenson, Tanel; Hauryliuk, Vasili (2011-08-09). "The RelA/SpoT Homolog (RSH) Superfamily: Distribution and Functional Evolution of ppGpp Synthetases and Hydrolases across the Tree of Life". PLOS ONE. 6 (8) e23479. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...623479A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023479. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3153485. PMID 21858139.

- ^ Nagano N, Orengo CA, Thornton JM (August 2002). "One fold with many functions: the evolutionary relationships between TIM barrel families based on their sequences, structures and functions". Journal of Molecular Biology. 321 (5): 741–65. doi:10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00649-6. PMID 12206759.

- ^ Farber G (1993). "An α/β-barrel full of evolutionary trouble". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 3 (3): 409–412. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(05)80114-9.

External links

[edit] Media related to Protein superfamilies at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Protein superfamilies at Wikimedia Commons