Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pyelonephritis

View on Wikipedia

| Pyelonephritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Kidney infection[1] |

| |

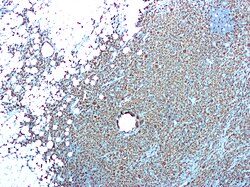

| CD68 immunostaining on this photomicrograph shows macrophages and giant cells in a case of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, urology, nephrology |

| Symptoms | Fever, flank tenderness, nausea, burning with urination, frequent urination[2] |

| Causes | Bacterial infection[2] |

| Risk factors | Sexual intercourse, prior urinary tract infections, diabetes, structural problems of the urinary tract, spermicide use[2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and supported by urinalysis[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, kidney stones[2] |

| Prevention | Urination after sex, drinking sufficient fluids[1] |

| Medication | Antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone)[4] |

| Frequency | Common[5] |

Pyelonephritis is inflammation of the kidney, typically due to a bacterial infection.[3] Symptoms most often include fever and flank tenderness.[2] Other symptoms may include nausea, burning with urination, and frequent urination.[2] Complications may include pus around the kidney, sepsis, or kidney failure.[3]

It is typically due to a bacterial infection, most commonly Escherichia coli.[2] Risk factors include sexual intercourse, prior urinary tract infections, diabetes, structural problems of the urinary tract, and spermicide use.[2][3] The mechanism of infection is usually spread up the urinary tract.[2] Less often infection occurs through the bloodstream.[1] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms and supported by urinalysis.[2] If there is no improvement with treatment, medical imaging may be recommended.[2]

Pyelonephritis may be preventable by urination after sex and drinking sufficient fluids.[1] Once present it is generally treated with antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin or ceftriaxone.[4][6] Those with severe disease may require treatment in hospital.[2] In those with certain structural problems of the urinary tract or kidney stones, surgery may be required.[1][3]

Pyelonephritis affects about 1 to 2 per 1,000 women each year and just under 0.5 per 1,000 males.[5][7] Young adult females are most often affected, followed by the very young and old.[2] With treatment, outcomes are generally good in young adults.[3][5] Among people over the age of 65 the risk of death is about 40%, though this depends on the health of the elderly person, the precise organism involved, and how quickly they can get care through a provider or in hospital.[5]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Signs and symptoms of acute pyelonephritis generally develop rapidly over a few hours or a day. It can cause high fever, pain on passing urine, and abdominal pain that radiates along the flank towards the back. There is often associated vomiting.[9]

Chronic pyelonephritis causes persistent flank or abdominal pain, signs of infection (fever, unintentional weight loss, malaise, decreased appetite), lower urinary tract symptoms and blood in the urine.[10] Chronic pyelonephritis can in addition cause fever of unknown origin. Furthermore, inflammation-related proteins can accumulate in organs and cause the condition AA amyloidosis.[11]

Physical examination may reveal fever and tenderness at the costovertebral angle on the affected side.[12]

Causes

[edit]Most cases of community-acquired pyelonephritis are due to bowel organisms that enter the urinary tract. Common organisms are E. coli (70–80%) and Enterococcus faecalis. Hospital-acquired infections may be due to coliform bacteria and enterococci, as well as other organisms uncommon in the community (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and various species of Klebsiella). Most cases of pyelonephritis start off as lower urinary tract infections, mainly cystitis and prostatitis.[9] E. coli can invade the superficial umbrella cells of the bladder to form intracellular bacterial communities (IBCs), which can mature into biofilms. These biofilm-producing E. coli are resistant to antibiotic therapy and immune system responses, and present a possible explanation for recurrent urinary tract infections, including pyelonephritis.[13] Risk is increased in the following situations:[9][14]

- Mechanical: any structural abnormalities in the urinary tract, vesicoureteral reflux (urine from the bladder flowing back into the ureter), kidney stones, urinary tract catheterization, ureteral stents or drainage procedures (e.g., nephrostomy), pregnancy, neurogenic bladder (e.g., due to spinal cord damage, spina bifida or multiple sclerosis) and prostate disease (e.g., benign prostatic hyperplasia) in men

- Constitutional: diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised states

- Behavioral: change in sexual partner within the last year, spermicide use

- Positive family history (close family members with frequent urinary tract infections)

Diagnosis

[edit]Laboratory examination

[edit]Analysis of the urine may show signs of urinary tract infection. Specifically, the presence of nitrite and white blood cells on a urine test strip in patients with typical symptoms are sufficient for the diagnosis of pyelonephritis, and are an indication for empirical treatment. Blood tests such as a complete blood count may show neutrophilia. Microbiological culture of the urine, with or without blood cultures and antibiotic sensitivity testing are useful for establishing a formal diagnosis,[9] and are considered mandatory.[15]

Imaging studies

[edit]If a kidney stone is suspected (e.g. on the basis of characteristic colicky pain or the presence of a disproportionate amount of blood in the urine), a kidneys, ureters, and bladder x-ray (KUB film) may assist in identifying radioopaque stones.[9] Where available, a noncontrast helical CT scan with 5 millimeter sections is the diagnostic modality of choice in the radiographic evaluation of suspected nephrolithiasis.[16][17][18] All stones are detectable on CT scans except very rare stones composed of certain drug residues in the urine.[19] In patients with recurrent ascending urinary tract infections, it may be necessary to exclude an anatomical abnormality, such as vesicoureteral reflux or polycystic kidney disease. Investigations used in this setting include kidney ultrasonography or voiding cystourethrography.[9] CT scan or kidney ultrasonography is useful in the diagnosis of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis; serial imaging may be useful for differentiating this condition from kidney cancer.[10]

Ultrasound findings that indicate pyelonephritis are enlargement of the kidney, edema in the renal sinus or parenchyma, bleeding, loss of corticomedullary differentiation, abscess formation, or an areas of poor blood flow on doppler ultrasound.[21] However, ultrasound findings are seen in only 20–24% of people with pyelonephritis.[21]

A DMSA scan is a radionuclide scan that uses dimercaptosuccinic acid in assessing the kidney morphology. It is now[when?] the most reliable test for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis.[22]

Classification

[edit]Acute pyelonephritis

[edit]Acute pyelonephritis is an exudative purulent localized inflammation of the renal pelvis (collecting system) and kidney. The kidney parenchyma presents in the interstitium abscesses (suppurative necrosis), consisting in purulent exudate (pus): neutrophils, fibrin, cell debris and central germ colonies (hematoxylinophils). Tubules are damaged by exudate and may contain neutrophil casts. In the early stages, the glomerulus and vessels are normal. Gross pathology often reveals pathognomonic radiations of bleeding and suppuration through the renal pelvis to the renal cortex.[citation needed]

Chronic pyelonephritis

[edit]Chronic pyelonephritis implies recurrent kidney infections and can result in scarring of the renal parenchyma and impaired function, especially in the setting of obstruction. A perinephric abscess (infection around the kidney) and/or pyonephrosis may develop in severe cases of pyelonephritis.[23]

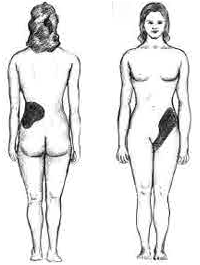

-

Abscess around both kidneys[24]

-

Abscess around both kidneys[24]

-

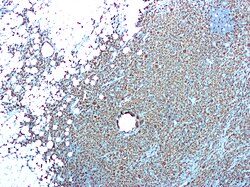

Chronic pyelonephritis with reduced kidney size and focal cortical thinning. Measurement of kidney length on the US image is illustrated by '+' and a dashed line.[20]

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis

[edit]Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is an unusual form of chronic pyelonephritis characterized by granulomatous abscess formation, severe kidney destruction, and a clinical picture that may resemble renal cell carcinoma and other inflammatory kidney parenchymal diseases. Most affected individuals present with recurrent fevers and urosepsis, anemia, and a painful kidney mass. Other common manifestations include kidney stones and loss of function of the affected kidney. Bacterial cultures of kidney tissue are almost always positive.[25] Microscopically, there are granulomas and lipid-laden macrophages (hence the term xantho-, which means yellow in ancient Greek). It is found in roughly 20% of specimens from surgically managed cases of pyelonephritis.[10]

Prevention

[edit]In people who experience recurrent urinary tract infections, additional investigations may identify an underlying abnormality. Occasionally, surgical intervention is necessary to reduce the likelihood of recurrence. If no abnormality is identified, some studies suggest long-term preventive treatment with antibiotics, either daily or after sexual activity.[26] In children at risk for recurrent urinary tract infections, not enough studies have been performed to conclude prescription of long-term antibiotics has a net positive benefit.[27] Cranberry products and drinking cranberry juice appears to provide a benefit in decreasing urinary tract infections for certain groups of individuals.[28]

Management

[edit]In people suspected of having pyelonephritis, a urine culture and antibiotic sensitivity test is performed, so therapy can eventually be tailored on the basis of the infecting organism.[5] As most cases of pyelonephritis are due to bacterial infections, antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment.[5] The choice of antibiotic depends on the species and antibiotic sensitivity profile of the infecting organism, and may include fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, either alone or in combination.[15]

Simple

[edit]A 2018 systematic review recommended the use of norfloxacin as it has the lowest rate of side effects with a comparable efficacy to commonly used antibiotics.[29]

In people who do not require hospitalization and live in an area where there is a low prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, a fluoroquinolone by mouth such as ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin is an appropriate initial choice for therapy.[5] In areas where there is a higher prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance, it is useful to initiate treatment with a single intravenous dose of a long-acting antibiotic such as ceftriaxone or an aminoglycoside, and then continuing treatment with a fluoroquinolone. Oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is an appropriate choice for therapy if the bacteria is known to be susceptible.[5] If trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is used when the susceptibility is not known, it is useful to initiate treatment with a single intravenous dose of a long-acting antibiotic such as ceftriaxone or an aminoglycoside. Oral beta-lactam antibiotics are less effective than other available agents for treatment of pyelonephritis.[15] Improvement is expected in 48 to 72 hours.[5]

Complicated

[edit]People with acute pyelonephritis that is accompanied by high fever and leukocytosis are typically admitted to the hospital for intravenous hydration and intravenous antibiotic treatment. Treatment is typically initiated with an intravenous fluoroquinolone, an aminoglycoside, an extended-spectrum penicillin or cephalosporin, or a carbapenem. Combination antibiotic therapy is often used in such situations. The treatment regimen is selected based on local resistance data and the susceptibility profile of the specific infecting organism(s).[15]

During the course of antibiotic treatment, serial white blood cell count and temperature are closely monitored. Typically, the intravenous antibiotics are continued until the person has no fever for at least 24 to 48 hours, then equivalent antibiotics by mouth can be given for a total of two-week duration of treatment.[30] Intravenous fluids may be administered to compensate for the reduced oral intake, insensible losses (due to the raised temperature) and vasodilation and to optimize urine output. Percutaneous nephrostomy or ureteral stent placement may be indicated to relieve obstruction caused by a stone. Children with acute pyelonephritis can be treated effectively with oral antibiotics (cefixime, ceftibuten and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) or with short courses (2 to 4 days) of intravenous therapy followed by oral therapy.[31] If intravenous therapy is chosen, single daily dosing with aminoglycosides is safe and effective.[31]

Fosfomycin can be used as an efficacious treatment for both UTIs and complicated UTIs including acute pyelonephritis. The standard regimen for complicated UTIs is an oral 3 g dose administered once every 48 or 72 hours for a total of 3 doses or a 6 grams every 8 hours for 7 days to 14 days when fosfomycin is given in IV form.[32]

Treatment of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis involves antibiotics as well as surgery. Removal of the kidney is the best surgical treatment in the overwhelming majority of cases, although polar resection (partial nephrectomy) has been effective for some people with localized disease.[10][33] Watchful waiting with serial imaging may be appropriate in rare circumstances.[34]

Follow-up

[edit]If no improvement is made in one to two days post therapy, inpatients should repeat a urine analysis and imaging. Outpatients should check again with their doctor.[35]

Epidemiology

[edit]There are roughly 12–13 cases annually per 10,000 population in women receiving outpatient treatment and 3–4 cases requiring admission. In men, 2–3 cases per 10,000 are treated as outpatients and 1–2 cases/10,000 require admission.[36] Young women are most often affected. Infants and the elderly are also at increased risk, reflecting anatomical changes and hormonal status.[36] Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is most common in middle-aged women.[25] It can present somewhat differently in children, in whom it may be mistaken for Wilms' tumor.[37]

Research

[edit]According to a 2015 meta analysis, vitamin A has been shown to alleviate renal damage and/or prevent renal scarring.[38]

Terminology

[edit]The term is from Greek πύελο|ς pýelo|s, "basin" + νεφρ|ός nepʰrós, "kidney" + suffix -itis suggesting "inflammation".[citation needed]

A similar term is "pyelitis", which means inflammation of the renal pelvis and calyces.[39][40] In other words, pyelitis together with nephritis is collectively known as pyelonephritis.[citation needed]

Etymology

[edit]The word pyelonephritis is formed by the Greek roots pyelo- from πύελος (púelos) renal pelvis and nephro- from νεφρός (nephrós) kidney together with the suffix -itis from -ῖτις (-itis) used in medicine to indicate diseases or inflammations.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Kidney Infection (Pyelonephritis)". NIDDK. April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Colgan R, Williams M, Johnson JR (September 2011). "Diagnosis and treatment of acute pyelonephritis in women". American Family Physician. 84 (5): 519–526. PMID 21888302.

- ^ a b c d e f Lippincott's Guide to Infectious Diseases. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-60547-975-0. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Antibiotic therapy for acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis in women. Take resistance into account". Prescrire International. 23 (155): 296–300. December 2014. PMID 25629148.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ferri FF (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1097. ISBN 978-0-323-52957-0. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, et al. (March 2011). "International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 52 (5): e103 – e120. doi:10.1093/cid/ciq257. PMID 21292654.

- ^ Lager DJ, Abrahams N (2012). Practical Renal Pathology, A Diagnostic Approach E-Book: A Volume in the Pattern Recognition Series. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-4557-3786-4. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Urinary Tract Infection Common Clinical and Laboratory Features of Acute Pyelonephritis". netterimages.com. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Ramakrishnan K, Scheid DC (March 2005). "Diagnosis and management of acute pyelonephritis in adults". American Family Physician. 71 (5): 933–942. PMID 15768623. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d Korkes F, Favoretto RL, Bróglio M, Silva CA, Castro MG, Perez MD (February 2008). "Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: clinical experience with 41 cases". Urology. 71 (2): 178–180. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.026. PMID 18308077.

- ^ Herrera GA, Picken MM (2007). "Chapter 19: Renal Diseases". In Jennette JC, Olson JL, Schwartz MM, Silva FG (eds.). Heptinstall's Pathology of the Kidney. Vol. 2 (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 853–910. ISBN 978-0-7817-4750-9. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- ^ Weiss M, Liapis H, Tomaszewski JE, Arend LJ (2007). "Chapter 22: Pyelonephritis and other infections, reflux nephropathy, hydronephrosis, and nephrolithiasis". In Jennette JC, Olson JL, Schwartz MM, Silva FG (eds.). Heptinstall's Pathology of the Kidney. Vol. 2 (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 991–1082. ISBN 978-0-7817-4750-9.

- ^ Hultgren SJ (2011). "Pathogenic Cascade of E. coli UTI". UTI Pathogenesis. St. Louis, Missouri: Molecular Microbiology and Microbial Pathogenesis Program, Washington University. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Scholes D, Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Gupta K, Stapleton AE, Stamm WE (January 2005). "Risk factors associated with acute pyelonephritis in healthy women". Annals of Internal Medicine. 142 (1): 20–27. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00008. PMC 3722605. PMID 15630106.

- ^ a b c d Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, et al. (March 2011). "International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 52 (5): e103 – e120. doi:10.1093/cid/ciq257. PMID 21292654.

- ^ Pearle MS, Calhoun EA, Curhan GC (2007). "Chapter 8: Urolithiasis" (PDF). In Litwin MS, Saigal CS (eds.). Urologic Diseases in America (NIH Publication No. 07–5512). Bethesda, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. pp. 283–319. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2011.

- ^ Smith RC, Varanelli M (July 2000). "Diagnosis and management of acute ureterolithiasis: CT is truth". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 175 (1): 3–6. doi:10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750003. PMID 10882237. S2CID 73387308.

- ^ Fang LS (2009). "Chapter 135: Approach to the Paient with Nephrolithiasis". In Goroll AH, Mulley AG (eds.). Primary care medicine: office evaluation and management of the adult patient (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 962–7. ISBN 978-0-7817-7513-7.

- ^ Pietrow PK, Karellas ME (July 2006). "Medical management of common urinary calculi" (PDF). American Family Physician. 74 (1): 86–94. PMID 16848382. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2011.

- ^ a b Content initially copied from: Hansen KL, Nielsen MB, Ewertsen C (December 2015). "Ultrasonography of the Kidney: A Pictorial Review". Diagnostics. 6 (1): 2. doi:10.3390/diagnostics6010002. PMC 4808817. PMID 26838799.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b Craig WD, Wagner BJ, Travis MD (2008). "Pyelonephritis: radiologic-pathologic review". Radiographics. 28 (1): 255–276. doi:10.1148/rg.281075171. PMID 18203942.

- ^ Goldraich NP, Goldraich IH (April 1995). "Update on dimercaptosuccinic acid renal scanning in children with urinary tract infection". Pediatric Nephrology. 9 (2): 221–6, discussion 227. doi:10.1007/bf00860755. PMID 7794724. S2CID 34078339.

- ^ Griebling TL (2007). "Chapter 18: Urinary Tract Infection in Women" (PDF). In Litwin MS, Saigal CS (eds.). Urologic Diseases in America (NIH Publication No. 07–5512). Bethesda, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. pp. 589–619. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ a b "UOTW #72 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 11 July 2016. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b Malek RS, Elder JS (May 1978). "Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: a critical analysis of 26 cases and of the literature". The Journal of Urology. 119 (5): 589–593. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57559-x. PMID 660725.

- ^ Schooff M, Hill K (April 2005). "Antibiotics for recurrent urinary tract infections". American Family Physician. 71 (7): 1301–1302. PMID 15832532.

- ^ Williams G, Craig JC (April 2019). "Long-term antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4) CD001534. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001534.pub4. PMC 6442022. PMID 30932167.

- ^ Williams G, Stothart CI, Hahn D, Stephens JH, Craig JC, Hodson EM (November 2023). "Cranberries for preventing urinary tract infections". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (11) CD001321. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001321.pub7. PMC 10636779. PMID 37947276.

- ^ Cattrall JW, Robinson AV, Kirby A (December 2018). "A systematic review of randomised clinical trials for oral antibiotic treatment of acute pyelonephritis". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 37 (12): 2285–2291. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3371-y. PMID 30191339.

- ^ Cabellon M (2005). "Chapter 8: Urinary Tract Infections". In Starlin R (ed.). The Washington Manual: Infectious Diseases Subspecialty Consult (1st ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 95–108. ISBN 978-0-7817-4373-0. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013.

- ^ a b Strohmeier Y, Hodson EM, Willis NS, Webster AC, Craig JC (July 2014). "Antibiotics for acute pyelonephritis in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (7) CD003772. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003772.pub4. hdl:2123/22283. PMC 10580126. PMID 25066627.

- ^ Zhanel GG, Zhanel MA, Karlowsky JA (28 March 2020). "Oral and Intravenous Fosfomycin for the Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections". The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology. 2020 8513405. doi:10.1155/2020/8513405. PMC 7142339. PMID 32300381.

- ^ Rosi P, Selli C, Carini M, Rosi MF, Mottola A (1986). "Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: clinical experience with 62 cases". European Urology. 12 (2): 96–100. doi:10.1159/000472589. PMID 3956552.

- ^ Lebret T, Poulain JE, Molinie V, Herve JM, Denoux Y, Guth A, et al. (October 2007). "Percutaneous core biopsy for renal masses: indications, accuracy and results". The Journal of Urology. 178 (4 Pt 1): 1184–8, discussion 1188. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.155. PMID 17698122.

- ^ Johnson JR, Russo TA (January 2018). "Acute Pyelonephritis in Adults". The New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (1): 48–59. doi:10.1056/nejmcp1702758. PMID 29298155. S2CID 3919412.

- ^ a b Czaja CA, Scholes D, Hooton TM, Stamm WE (August 2007). "Population-based epidemiologic analysis of acute pyelonephritis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 45 (3): 273–280. doi:10.1086/519268. PMID 17599303.

- ^ Goodman TR, McHugh K, Lindsell DR (1998). "Paediatric xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 52 (1): 43–45. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.1998.tb11558.x. PMID 9536568. S2CID 28900400.

- ^ Zhang GQ, Chen JL, Zhao Y (March 2016). "The effect of vitamin A on renal damage following acute pyelonephritis in children: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Pediatric Nephrology. 31 (3): 373–379. doi:10.1007/s00467-015-3098-2. PMID 25980468. S2CID 24441322.

- ^ medilexicon.com Archived 6 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Using Medical Terminology: A Practical Approach 2006 p.723

External links

[edit]- Kidney Infection (Pyelonephritis) at the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

![Chronic pyelonephritis with reduced kidney size and focal cortical thinning. Measurement of kidney length on the US image is illustrated by '+' and a dashed line.[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Ultrasonography_of_chronic_pyelonephritis_with_reduced_kidney_size_and_focal_cortical_thinning.jpg/250px-Ultrasonography_of_chronic_pyelonephritis_with_reduced_kidney_size_and_focal_cortical_thinning.jpg)