Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reductive group

View on Wikipedia| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In mathematics, a reductive group is a type of linear algebraic group over a field. One definition is that a connected linear algebraic group G over a perfect field is reductive if it has a representation that has a finite kernel and is a direct sum of irreducible representations. Reductive groups include some of the most important groups in mathematics, such as the general linear group GL(n) of invertible matrices, the special orthogonal group SO(n), and the symplectic group Sp(2n). Simple algebraic groups and (more generally) semisimple algebraic groups are reductive.

Claude Chevalley showed that the classification of reductive groups is the same over any algebraically closed field. In particular, the simple algebraic groups are classified by Dynkin diagrams, as in the theory of compact Lie groups or complex semisimple Lie algebras. Reductive groups over an arbitrary field are harder to classify, but for many fields such as the real numbers R or a number field, the classification is well understood. The classification of finite simple groups says that most finite simple groups arise as the group G(k) of k-rational points of a simple algebraic group G over a finite field k, or as minor variants of that construction.

Reductive groups have a rich representation theory in various contexts. First, one can study the representations of a reductive group G over a field k as an algebraic group, which are actions of G on k-vector spaces. But also, one can study the complex representations of the group G(k) when k is a finite field, or the infinite-dimensional unitary representations of a real reductive group, or the automorphic representations of an adelic algebraic group. The structure theory of reductive groups is used in all these areas.

Definitions

[edit]A linear algebraic group over a field k is defined as a smooth closed subgroup scheme of GL(n) over k, for some positive integer n. Equivalently, a linear algebraic group over k is a smooth affine group scheme over k.

With the unipotent radical

[edit]A connected linear algebraic group over an algebraically closed field is called semisimple if every smooth connected solvable normal subgroup of is trivial. More generally, a connected linear algebraic group over an algebraically closed field is called reductive if the largest smooth connected unipotent normal subgroup of is trivial.[1] This normal subgroup is called the unipotent radical and is denoted . (Some authors do not require reductive groups to be connected.) A group over an arbitrary field k is called semisimple or reductive if the base change is semisimple or reductive, where is an algebraic closure of k. (This is equivalent to the definition of reductive groups in the introduction when k is perfect.[2]) Any torus over k, such as the multiplicative group Gm, is reductive.

With representation theory

[edit]Over fields of characteristic zero another equivalent definition of a reductive group is a connected group admitting a faithful semisimple representation which remains semisimple over its algebraic closure [3] page 424.

Simple reductive groups

[edit]A linear algebraic group G over a field k is called simple (or k-simple) if it is semisimple, nontrivial, and every smooth connected normal subgroup of G over k is trivial or equal to G.[4] (Some authors call this property "almost simple".) This differs slightly from the terminology for abstract groups, in that a simple algebraic group may have nontrivial center (although the center must be finite). For example, for any integer n at least 2 and any field k, the group SL(n) over k is simple, and its center is the group scheme μn of nth roots of unity.

A central isogeny of reductive groups is a surjective homomorphism with kernel a finite central subgroup scheme. Every reductive group over a field admits a central isogeny from the product of a torus and some simple groups. For example, over any field k,

It is slightly awkward that the definition of a reductive group over a field involves passage to the algebraic closure. For a perfect field k, that can be avoided: a linear algebraic group G over k is reductive if and only if every smooth connected unipotent normal k-subgroup of G is trivial. For an arbitrary field, the latter property defines a pseudo-reductive group, which is somewhat more general.

Split-reductive groups

[edit]A reductive group G over a field k is called split if it contains a split maximal torus T over k (that is, a split torus in G whose base change to is a maximal torus in ). It is equivalent to say that T is a split torus in G that is maximal among all k-tori in G.[5] These kinds of groups are useful because their classification can be described through combinatorical data called root data.

Examples

[edit]GLn and SLn

[edit]A fundamental example of a reductive group is the general linear group of invertible n × n matrices over a field k, for a natural number n. In particular, the multiplicative group Gm is the group GL(1), and so its group Gm(k) of k-rational points is the group k* of nonzero elements of k under multiplication. Another reductive group is the special linear group SL(n) over a field k, the subgroup of matrices with determinant 1. In fact, SL(n) is a simple algebraic group for n at least 2.

O(n), SO(n), and Sp(n)

[edit]An important simple group is the symplectic group Sp(2n) over a field k, the subgroup of GL(2n) that preserves a nondegenerate alternating bilinear form on the vector space k2n. Likewise, the orthogonal group O(q) is the subgroup of the general linear group that preserves a nondegenerate quadratic form q on a vector space over a field k. The algebraic group O(q) has two connected components, and its identity component SO(q) is reductive, in fact simple for q of dimension n at least 3. (For k of characteristic 2 and n odd, the group scheme O(q) is in fact connected but not smooth over k. The simple group SO(q) can always be defined as the maximal smooth connected subgroup of O(q) over k.) When k is algebraically closed, any two (nondegenerate) quadratic forms of the same dimension are isomorphic, and so it is reasonable to call this group SO(n). For a general field k, different quadratic forms of dimension n can yield non-isomorphic simple groups SO(q) over k, although they all have the same base change to the algebraic closure .

Tori

[edit]The group and products of it are called the algebraic tori. They are examples of reductive groups since they embed in through the diagonal, and from this representation, their unipotent radical is trivial. For example, embeds in from the map

Non-examples

[edit]- Any unipotent group is not reductive since its unipotent radical is itself. This includes the additive group .

- The Borel group of has a non-trivial unipotent radical of upper-triangular matrices with on the diagonal. This is an example of a non-reductive group which is not unipotent.

Associated reductive group

[edit]Note that the normality of the unipotent radical implies that the quotient group is reductive. For example,

Other characterizations of reductive groups

[edit]Every compact connected Lie group has a complexification, which is a complex reductive algebraic group. In fact, this construction gives a one-to-one correspondence between compact connected Lie groups and complex reductive groups, up to isomorphism. For a compact Lie group K with complexification G, the inclusion from K into the complex reductive group G(C) is a homotopy equivalence, with respect to the classical topology on G(C). For example, the inclusion from the unitary group U(n) to GL(n,C) is a homotopy equivalence.

For a reductive group G over a field of characteristic zero, all finite-dimensional representations of G (as an algebraic group) are completely reducible, that is, they are direct sums of irreducible representations.[6] That is the source of the name "reductive". Note, however, that complete reducibility fails for reductive groups in positive characteristic (apart from tori). In more detail: an affine group scheme G of finite type over a field k is called linearly reductive if its finite-dimensional representations are completely reducible. For k of characteristic zero, G is linearly reductive if and only if the identity component Go of G is reductive.[7] For k of characteristic p>0, however, Masayoshi Nagata showed that G is linearly reductive if and only if Go is of multiplicative type and G/Go has order prime to p.[8]

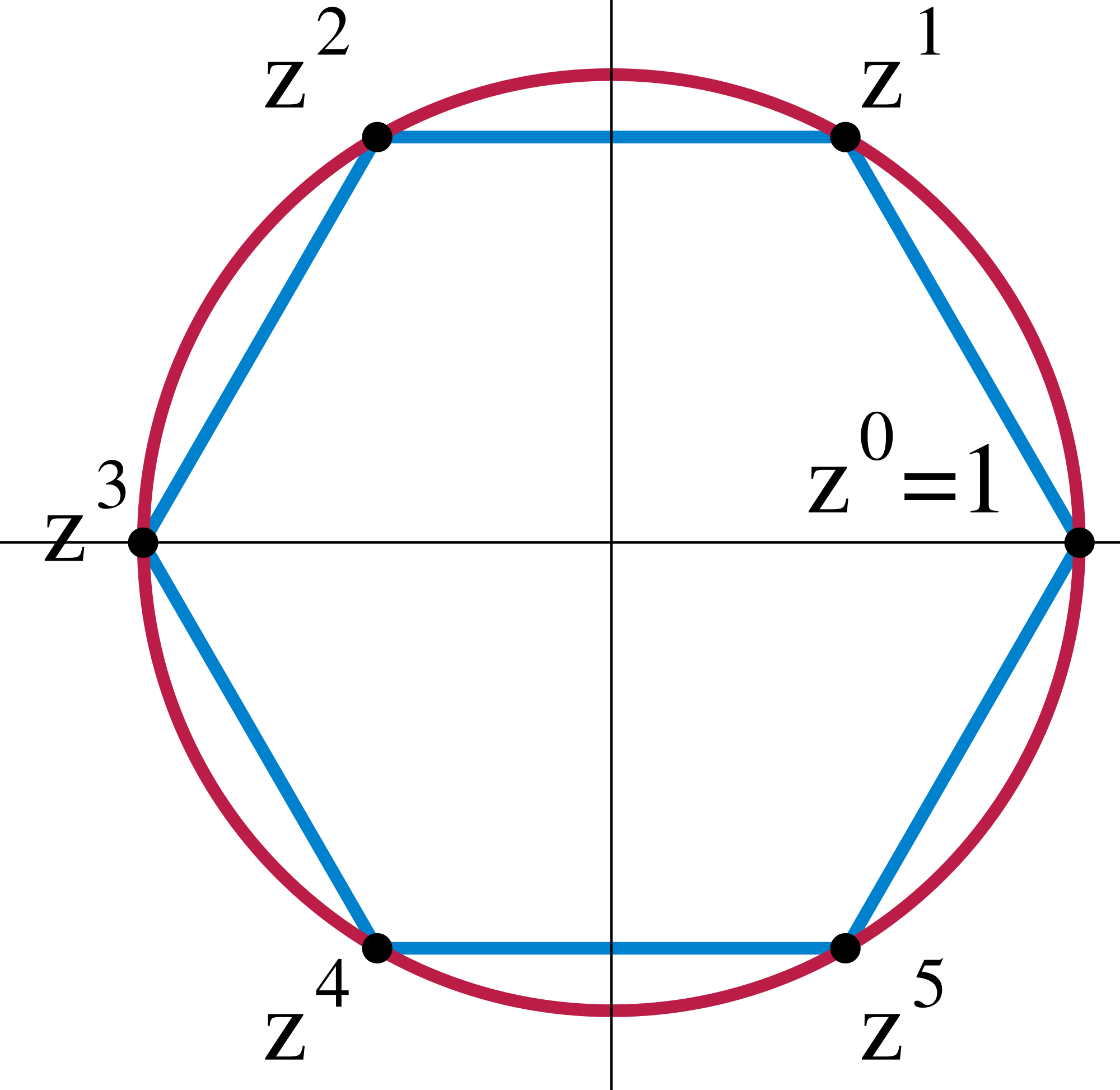

Roots

[edit]The classification of reductive algebraic groups is in terms of the associated root system, as in the theories of complex semisimple Lie algebras or compact Lie groups. Here is the way roots appear for reductive groups.

Let G be a split reductive group over a field k, and let T be a split maximal torus in G; so T is isomorphic to (Gm)n for some n, with n called the rank of G. Every representation of T (as an algebraic group) is a direct sum of 1-dimensional representations.[9] A weight for G means an isomorphism class of 1-dimensional representations of T, or equivalently a homomorphism T → Gm. The weights form a group X(T) under tensor product of representations, with X(T) isomorphic to the product of n copies of the integers, Zn.

The adjoint representation is the action of G by conjugation on its Lie algebra . A root of G means a nonzero weight that occurs in the action of T ⊂ G on . The subspace of corresponding to each root is 1-dimensional, and the subspace of fixed by T is exactly the Lie algebra of T.[10] Therefore, the Lie algebra of G decomposes into together with 1-dimensional subspaces indexed by the set Φ of roots:

For example, when G is the group GL(n), its Lie algebra is the vector space of all n × n matrices over k. Let T be the subgroup of diagonal matrices in G. Then the root-space decomposition expresses as the direct sum of the diagonal matrices and the 1-dimensional subspaces indexed by the off-diagonal positions (i, j). Writing L1,...,Ln for the standard basis for the weight lattice X(T) ≅ Zn, the roots are the elements Li − Lj for all i ≠ j from 1 to n.

The roots of a semisimple group form a root system; this is a combinatorial structure which can be completely classified. More generally, the roots of a reductive group form a root datum, a slight variation.[11] The Weyl group of a reductive group G means the quotient group of the normalizer of a maximal torus by the torus, W = NG(T)/T. The Weyl group is in fact a finite group generated by reflections. For example, for the group GL(n) (or SL(n)), the Weyl group is the symmetric group Sn.

There are finitely many Borel subgroups containing a given maximal torus, and they are permuted simply transitively by the Weyl group (acting by conjugation).[12] A choice of Borel subgroup determines a set of positive roots Φ+ ⊂ Φ, with the property that Φ is the disjoint union of Φ+ and −Φ+. Explicitly, the Lie algebra of B is the direct sum of the Lie algebra of T and the positive root spaces:

For example, if B is the Borel subgroup of upper-triangular matrices in GL(n), then this is the obvious decomposition of the subspace of upper-triangular matrices in . The positive roots are Li − Lj for 1 ≤ i < j ≤ n.

A simple root means a positive root that is not a sum of two other positive roots. Write Δ for the set of simple roots. The number r of simple roots is equal to the rank of the commutator subgroup of G, called the semisimple rank of G (which is simply the rank of G if G is semisimple). For example, the simple roots for GL(n) (or SL(n)) are Li − Li+1 for 1 ≤ i ≤ n − 1.

Root systems are classified by the corresponding Dynkin diagram, which is a finite graph (with some edges directed or multiple). The set of vertices of the Dynkin diagram is the set of simple roots. In short, the Dynkin diagram describes the angles between the simple roots and their relative lengths, with respect to a Weyl group-invariant inner product on the weight lattice. The connected Dynkin diagrams (corresponding to simple groups) are pictured below.

For a split reductive group G over a field k, an important point is that a root α determines not just a 1-dimensional subspace of the Lie algebra of G, but also a copy of the additive group Ga in G with the given Lie algebra, called a root subgroup Uα. The root subgroup is the unique copy of the additive group in G which is normalized by T and which has the given Lie algebra.[10] The whole group G is generated (as an algebraic group) by T and the root subgroups, while the Borel subgroup B is generated by T and the positive root subgroups. In fact, a split semisimple group G is generated by the root subgroups alone.

Parabolic subgroups

[edit]For a split reductive group G over a field k, the smooth connected subgroups of G that contain a given Borel subgroup B of G are in one-to-one correspondence with the subsets of the set Δ of simple roots (or equivalently, the subsets of the set of vertices of the Dynkin diagram). Let r be the order of Δ, the semisimple rank of G. Every parabolic subgroup of G is conjugate to a subgroup containing B by some element of G(k). As a result, there are exactly 2r conjugacy classes of parabolic subgroups in G over k.[13] Explicitly, the parabolic subgroup corresponding to a given subset S of Δ is the group generated by B together with the root subgroups U−α for α in S. For example, the parabolic subgroups of GL(n) that contain the Borel subgroup B above are the groups of invertible matrices with zero entries below a given set of squares along the diagonal, such as:

By definition, a parabolic subgroup P of a reductive group G over a field k is a smooth k-subgroup such that the quotient variety G/P is proper over k, or equivalently projective over k. Thus the classification of parabolic subgroups amounts to a classification of the projective homogeneous varieties for G (with smooth stabilizer group; that is no restriction for k of characteristic zero). For GL(n), these are the flag varieties, parametrizing sequences of linear subspaces of given dimensions a1,...,ai contained in a fixed vector space V of dimension n:

For the orthogonal group or the symplectic group, the projective homogeneous varieties have a similar description as varieties of isotropic flags with respect to a given quadratic form or symplectic form. For any reductive group G with a Borel subgroup B, G/B is called the flag variety or flag manifold of G.

Classification of split reductive groups

[edit]

Chevalley showed in 1958 that the reductive groups over any algebraically closed field are classified up to isomorphism by root data.[14] In particular, the semisimple groups over an algebraically closed field are classified up to central isogenies by their Dynkin diagram, and the simple groups correspond to the connected diagrams. Thus there are simple groups of types An, Bn, Cn, Dn, E6, E7, E8, F4, G2. This result is essentially identical to the classifications of compact Lie groups or complex semisimple Lie algebras, by Wilhelm Killing and Élie Cartan in the 1880s and 1890s. In particular, the dimensions, centers, and other properties of the simple algebraic groups can be read from the list of simple Lie groups. It is remarkable that the classification of reductive groups is independent of the characteristic. For comparison, there are many more simple Lie algebras in positive characteristic than in characteristic zero.

The exceptional groups G of type G2 and E6 had been constructed earlier, at least in the form of the abstract group G(k), by L. E. Dickson. For example, the group G2 is the automorphism group of an octonion algebra over k. By contrast, the Chevalley groups of type F4, E7, E8 over a field of positive characteristic were completely new.

More generally, the classification of split reductive groups is the same over any field.[15] A semisimple group G over a field k is called simply connected if every central isogeny from a semisimple group to G is an isomorphism. (For G semisimple over the complex numbers, being simply connected in this sense is equivalent to G(C) being simply connected in the classical topology.) Chevalley's classification gives that, over any field k, there is a unique simply connected split semisimple group G with a given Dynkin diagram, with simple groups corresponding to the connected diagrams. At the other extreme, a semisimple group is of adjoint type if its center is trivial. The split semisimple groups over k with given Dynkin diagram are exactly the groups G/A, where G is the simply connected group and A is a k-subgroup scheme of the center of G.

For example, the simply connected split simple groups over a field k corresponding to the "classical" Dynkin diagrams are as follows:

- An: SL(n+1) over k;

- Bn: the spin group Spin(2n+1) associated to a quadratic form of dimension 2n+1 over k with Witt index n, for example the form

- Cn: the symplectic group Sp(2n) over k;

- Dn: the spin group Spin(2n) associated to a quadratic form of dimension 2n over k with Witt index n, which can be written as:

The outer automorphism group of a split reductive group G over a field k is isomorphic to the automorphism group of the root datum of G. Moreover, the automorphism group of G splits as a semidirect product:

where Z is the center of G.[16] For a split semisimple simply connected group G over a field, the outer automorphism group of G has a simpler description: it is the automorphism group of the Dynkin diagram of G.

Reductive group schemes

[edit]A group scheme G over a scheme S is called reductive if the morphism G → S is smooth and affine, and every geometric fiber is reductive. (For a point p in S, the corresponding geometric fiber means the base change of G to an algebraic closure of the residue field of p.) Extending Chevalley's work, Michel Demazure and Grothendieck showed that pinned reductive group schemes over any nonempty scheme S are classified by root data.[17] This statement includes the existence of Chevalley groups as group schemes over Z, and it says that every pinned reductive group over a scheme S is isomorphic to the base change of a Chevalley group from Z to S. A pinning of a split reductive group is a choice of root basis and also a choice of trivialisation of the one-dimensional additive group corresponding to each simple root. This statement is false without the pinning; for example, suppose that A is a Dedekind domain and that I is an ideal in A whose class in the class group of A is not a square. Then SL(A + I) and SL_2(A) are split and reductive over Spec A and have the same root data but they are not isomorphic: the flag scheme (the quotient by a Borel subgroup scheme) of the first is the projective line bundle P(A + I) and has no section with trivial normal bundle (a section corresponds to a short exact sequence 0 → J → A + I → K → 0 where J, K are ideal classes and the normal bundle is then J^{-1}K, which is not trivial since JK is isomorphic to I) while the flag scheme of the second is P^1_A and does possess sections with trivial normal bundle.

Real reductive groups

[edit]In the context of Lie groups rather than algebraic groups, a real reductive group is a Lie group G such that there is a linear algebraic group L over R whose identity component (in the Zariski topology) is reductive, and a homomorphism G → L(R) whose kernel is finite and whose image is open in L(R) (in the classical topology). It is also standard to assume that the image of the adjoint representation Ad(G) is contained in Int(gC) = Ad(L0(C)) (which is automatic for G connected).[18]

In particular, every connected semisimple Lie group (meaning that its Lie algebra is semisimple) is reductive. Also, the Lie group R is reductive in this sense, since it can be viewed as the identity component of GL(1,R) ≅ R*. The problem of classifying the real reductive groups largely reduces to classifying the simple Lie groups. These are classified by their Satake diagram; or one can just refer to the list of simple Lie groups (up to finite coverings).

Useful theories of admissible representations and unitary representations have been developed for real reductive groups in this generality. The main differences between this definition and the definition of a reductive algebraic group have to do with the fact that an algebraic group G over R may be connected as an algebraic group while the Lie group G(R) is not connected, and likewise for simply connected groups.

For example, the projective linear group PGL(2) is connected as an algebraic group over any field, but its group of real points PGL(2,R) has two connected components. The identity component of PGL(2,R) (sometimes called PSL(2,R)) is a real reductive group that cannot be viewed as an algebraic group. Similarly, SL(2) is simply connected as an algebraic group over any field, but the Lie group SL(2,R) has fundamental group isomorphic to the integers Z, and so SL(2,R) has nontrivial covering spaces. By definition, all finite coverings of SL(2,R) (such as the metaplectic group) are real reductive groups. On the other hand, the universal cover of SL(2,R) is not a real reductive group, even though its Lie algebra is reductive, that is, the product of a semisimple Lie algebra and an abelian Lie algebra.

For a connected real reductive group G, the quotient manifold G/K of G by a maximal compact subgroup K is a symmetric space of non-compact type. In fact, every symmetric space of non-compact type arises this way. These are central examples in Riemannian geometry of manifolds with nonpositive sectional curvature. For example, SL(2,R)/SO(2) is the hyperbolic plane, and SL(2,C)/SU(2) is hyperbolic 3-space.

For a reductive group G over a field k that is complete with respect to a discrete valuation (such as the p-adic numbers Qp), the affine building X of G plays the role of the symmetric space. Namely, X is a simplicial complex with an action of G(k), and G(k) preserves a CAT(0) metric on X, the analog of a metric with nonpositive curvature. The dimension of the affine building is the k-rank of G. For example, the building of SL(2,Qp) is a tree.

Representations of reductive groups

[edit]For a split reductive group G over a field k, the irreducible representations of G (as an algebraic group) are parametrized by the dominant weights, which are defined as the intersection of the weight lattice X(T) ≅ Zn with a convex cone (a Weyl chamber) in Rn. In particular, this parametrization is independent of the characteristic of k. In more detail, fix a split maximal torus and a Borel subgroup, T ⊂ B ⊂ G. Then B is the semidirect product of T with a smooth connected unipotent subgroup U. Define a highest weight vector in a representation V of G over k to be a nonzero vector v such that B maps the line spanned by v into itself. Then B acts on that line through its quotient group T, by some element λ of the weight lattice X(T). Chevalley showed that every irreducible representation of G has a unique highest weight vector up to scalars; the corresponding "highest weight" λ is dominant; and every dominant weight λ is the highest weight of a unique irreducible representation L(λ) of G, up to isomorphism.[19]

There remains the problem of describing the irreducible representation with given highest weight. For k of characteristic zero, there are essentially complete answers. For a dominant weight λ, define the Schur module ∇(λ) as the k-vector space of sections of the G-equivariant line bundle on the flag manifold G/B associated to λ; this is a representation of G. For k of characteristic zero, the Borel–Weil theorem says that the irreducible representation L(λ) is isomorphic to the Schur module ∇(λ). Furthermore, the Weyl character formula gives the character (and in particular the dimension) of this representation.

For a split reductive group G over a field k of positive characteristic, the situation is far more subtle, because representations of G are typically not direct sums of irreducibles. For a dominant weight λ, the irreducible representation L(λ) is the unique simple submodule (the socle) of the Schur module ∇(λ), but it need not be equal to the Schur module. The dimension and character of the Schur module are given by the Weyl character formula (as in characteristic zero), by George Kempf.[20] The dimensions and characters of the irreducible representations L(λ) are in general unknown, although a large body of theory has been developed to analyze these representations. One important result is that the dimension and character of L(λ) are known when the characteristic p of k is much bigger than the Coxeter number of G, by Henning Andersen, Jens Jantzen, and Wolfgang Soergel (proving Lusztig's conjecture in that case). Their character formula for p large is based on the Kazhdan–Lusztig polynomials, which are combinatorially complex.[21] For any prime p, Simon Riche and Geordie Williamson conjectured the irreducible characters of a reductive group in terms of the p-Kazhdan-Lusztig polynomials, which are even more complex, but at least are computable.[22]

Non-split reductive groups

[edit]As discussed above, the classification of split reductive groups is the same over any field. By contrast, the classification of arbitrary reductive groups can be hard, depending on the base field. Some examples among the classical groups are:

- Every nondegenerate quadratic form q over a field k determines a reductive group G = SO(q). Here G is simple if q has dimension n at least 3, since is isomorphic to SO(n) over an algebraic closure . The k-rank of G is equal to the Witt index of q (the maximum dimension of an isotropic subspace over k).[23] So the simple group G is split over k if and only if q has the maximum possible Witt index, .

- Every central simple algebra A over k determines a reductive group G = SL(1,A), the kernel of the reduced norm on the group of units A* (as an algebraic group over k). The degree of A means the square root of the dimension of A as a k-vector space. Here G is simple if A has degree n at least 2, since is isomorphic to SL(n) over . If A has index r (meaning that A is isomorphic to the matrix algebra Mn/r(D) for a division algebra D of degree r over k), then the k-rank of G is (n/r) − 1.[24] So the simple group G is split over k if and only if A is a matrix algebra over k.

As a result, the problem of classifying reductive groups over k essentially includes the problem of classifying all quadratic forms over k or all central simple algebras over k. These problems are easy for k algebraically closed, and they are understood for some other fields such as number fields, but for arbitrary fields there are many open questions.

A reductive group over a field k is called isotropic if it has k-rank greater than 0 (that is, if it contains a nontrivial split torus), and otherwise anisotropic. For a semisimple group G over a field k, the following conditions are equivalent:

- G is isotropic (that is, G contains a copy of the multiplicative group Gm over k);

- G contains a parabolic subgroup over k not equal to G;

- G contains a copy of the additive group Ga over k.

For k perfect, it is also equivalent to say that G(k) contains a unipotent element other than 1.[25]

For a connected linear algebraic group G over a local field k of characteristic zero (such as the real numbers), the group G(k) is compact in the classical topology (based on the topology of k) if and only if G is reductive and anisotropic.[26] Example: the orthogonal group SO(p,q) over R has real rank min(p,q), and so it is anisotropic if and only if p or q is zero.[23]

A reductive group G over a field k is called quasi-split if it contains a Borel subgroup over k. A split reductive group is quasi-split. If G is quasi-split over k, then any two Borel subgroups of G are conjugate by some element of G(k).[27] Example: the orthogonal group SO(p,q) over R is split if and only if |p−q| ≤ 1, and it is quasi-split if and only if |p−q| ≤ 2.[23]

Structure of semisimple groups as abstract groups

[edit]For a simply connected split semisimple group G over a field k, Robert Steinberg gave an explicit presentation of the abstract group G(k).[28] It is generated by copies of the additive group of k indexed by the roots of G (the root subgroups), with relations determined by the Dynkin diagram of G.

For a simply connected split semisimple group G over a perfect field k, Steinberg also determined the automorphism group of the abstract group G(k). Every automorphism is the product of an inner automorphism, a diagonal automorphism (meaning conjugation by a suitable -point of a maximal torus), a graph automorphism (corresponding to an automorphism of the Dynkin diagram), and a field automorphism (coming from an automorphism of the field k).[29]

For a k-simple algebraic group G, Tits's simplicity theorem says that the abstract group G(k) is close to being simple, under mild assumptions. Namely, suppose that G is isotropic over k, and suppose that the field k has at least 4 elements. Let G(k)+ be the subgroup of the abstract group G(k) generated by k-points of copies of the additive group Ga over k contained in G. (By the assumption that G is isotropic over k, the group G(k)+ is nontrivial, and even Zariski dense in G if k is infinite.) Then the quotient group of G(k)+ by its center is simple (as an abstract group).[30] The proof uses Jacques Tits's machinery of BN-pairs.

The exceptions for fields of order 2 or 3 are well understood. For k = F2, Tits's simplicity theorem remains valid except when G is split of type A1, B2, or G2, or non-split (that is, unitary) of type A2. For k = F3, the theorem holds except for G of type A1.[31]

For a k-simple group G, in order to understand the whole group G(k), one can consider the Whitehead group W(k,G)=G(k)/G(k)+. For G simply connected and quasi-split, the Whitehead group is trivial, and so the whole group G(k) is simple modulo its center.[32] More generally, the Kneser–Tits problem asks for which isotropic k-simple groups the Whitehead group is trivial. In all known examples, W(k,G) is abelian.

For an anisotropic k-simple group G, the abstract group G(k) can be far from simple. For example, let D be a division algebra with center a p-adic field k. Suppose that the dimension of D over k is finite and greater than 1. Then G = SL(1,D) is an anisotropic k-simple group. As mentioned above, G(k) is compact in the classical topology. Since it is also totally disconnected, G(k) is a profinite group (but not finite). As a result, G(k) contains infinitely many normal subgroups of finite index.[33]

Lattices and arithmetic groups

[edit]Let G be a linear algebraic group over the rational numbers Q. Then G can be extended to an affine group scheme G over Z, and this determines an abstract group G(Z). An arithmetic group means any subgroup of G(Q) that is commensurable with G(Z). (Arithmeticity of a subgroup of G(Q) is independent of the choice of Z-structure.) For example, SL(n,Z) is an arithmetic subgroup of SL(n,Q).

For a Lie group G, a lattice in G means a discrete subgroup Γ of G such that the manifold G/Γ has finite volume (with respect to a G-invariant measure). For example, a discrete subgroup Γ is a lattice if G/Γ is compact. The Margulis arithmeticity theorem says, in particular: for a simple Lie group G of real rank at least 2, every lattice in G is an arithmetic group.

The Galois action on the Dynkin diagram

[edit]In seeking to classify reductive groups which need not be split, one step is the Tits index, which reduces the problem to the case of anisotropic groups. This reduction generalizes several fundamental theorems in algebra. For example, Witt's decomposition theorem says that a nondegenerate quadratic form over a field is determined up to isomorphism by its Witt index together with its anisotropic kernel. Likewise, the Artin–Wedderburn theorem reduces the classification of central simple algebras over a field to the case of division algebras. Generalizing these results, Tits showed that a reductive group over a field k is determined up to isomorphism by its Tits index together with its anisotropic kernel, an associated anisotropic semisimple k-group.

For a reductive group G over a field k, the absolute Galois group Gal(ks/k) acts (continuously) on the "absolute" Dynkin diagram of G, that is, the Dynkin diagram of G over a separable closure ks (which is also the Dynkin diagram of G over an algebraic closure ). The Tits index of G consists of the root datum of Gks, the Galois action on its Dynkin diagram, and a Galois-invariant subset of the vertices of the Dynkin diagram. Traditionally, the Tits index is drawn by circling the Galois orbits in the given subset.

There is a full classification of quasi-split groups in these terms. Namely, for each action of the absolute Galois group of a field k on a Dynkin diagram, there is a unique simply connected semisimple quasi-split group H over k with the given action. (For a quasi-split group, every Galois orbit in the Dynkin diagram is circled.) Moreover, any other simply connected semisimple group G over k with the given action is an inner form of the quasi-split group H, meaning that G is the group associated to an element of the Galois cohomology set H1(k,H/Z), where Z is the center of H. In other words, G is the twist of H associated to some H/Z-torsor over k, as discussed in the next section.

Example: Let q be a nondegenerate quadratic form of even dimension 2n over a field k of characteristic not 2, with n ≥ 5. (These restrictions can be avoided.) Let G be the simple group SO(q) over k. The absolute Dynkin diagram of G is of type Dn, and so its automorphism group is of order 2, switching the two "legs" of the Dn diagram. The action of the absolute Galois group of k on the Dynkin diagram is trivial if and only if the signed discriminant d of q in k*/(k*)2 is trivial. If d is nontrivial, then it is encoded in the Galois action on the Dynkin diagram: the index-2 subgroup of the Galois group that acts as the identity is . The group G is split if and only if q has Witt index n, the maximum possible, and G is quasi-split if and only if q has Witt index at least n − 1.[23]

Torsors and the Hasse principle

[edit]A torsor for an affine group scheme G over a field k means an affine scheme X over k with an action of G such that is isomorphic to with the action of on itself by left translation. A torsor can also be viewed as a principal G-bundle over k with respect to the fppf topology on k, or the étale topology if G is smooth over k. The pointed set of isomorphism classes of G-torsors over k is called H1(k,G), in the language of Galois cohomology.

Torsors arise whenever one seeks to classify forms of a given algebraic object Y over a field k, meaning objects X over k which become isomorphic to Y over the algebraic closure of k. Namely, such forms (up to isomorphism) are in one-to-one correspondence with the set H1(k,Aut(Y)). For example, (nondegenerate) quadratic forms of dimension n over k are classified by H1(k,O(n)), and central simple algebras of degree n over k are classified by H1(k,PGL(n)). Also, k-forms of a given algebraic group G (sometimes called "twists" of G) are classified by H1(k,Aut(G)). These problems motivate the systematic study of G-torsors, especially for reductive groups G.

When possible, one hopes to classify G-torsors using cohomological invariants, which are invariants taking values in Galois cohomology with abelian coefficient groups M, Ha(k,M). In this direction, Steinberg proved Serre's "Conjecture I": for a connected linear algebraic group G over a perfect field of cohomological dimension at most 1, H1(k,G) = 1.[34] (The case of a finite field was known earlier, as Lang's theorem.) It follows, for example, that every reductive group over a finite field is quasi-split.

Serre's Conjecture II predicts that for a simply connected semisimple group G over a field of cohomological dimension at most 2, H1(k,G) = 1. The conjecture is known for a totally imaginary number field (which has cohomological dimension 2). More generally, for any number field k, Martin Kneser, Günter Harder and Vladimir Chernousov (1989) proved the Hasse principle: for a simply connected semisimple group G over k, the map

is bijective.[35] Here v runs over all places of k, and kv is the corresponding local field (possibly R or C). Moreover, the pointed set H1(kv,G) is trivial for every nonarchimidean local field kv, and so only the real places of k matter. The analogous result for a global field k of positive characteristic was proved earlier by Harder (1975): for every simply connected semisimple group G over k, H1(k,G) is trivial (since k has no real places).[36]

In the slightly different case of an adjoint group G over a number field k, the Hasse principle holds in a weaker form: the natural map

is injective.[37] For G = PGL(n), this amounts to the Albert–Brauer–Hasse–Noether theorem, saying that a central simple algebra over a number field is determined by its local invariants.

Building on the Hasse principle, the classification of semisimple groups over number fields is well understood. For example, there are exactly three Q-forms of the exceptional group E8, corresponding to the three real forms of E8.

See also

[edit]- The groups of Lie type are the finite simple groups constructed from simple algebraic groups over finite fields.

- Generalized flag variety, Bruhat decomposition, Schubert variety, Schubert calculus

- Schur algebra, Deligne–Lusztig theory

- Real form (Lie theory)

- Weil's conjecture on Tamagawa numbers

- Langlands classification, Langlands dual group, Langlands program, geometric Langlands program

- Special group, essential dimension

- Geometric invariant theory, Luna's slice theorem, Haboush's theorem

- Radical of an algebraic group

Notes

[edit]- ^ SGA 3 (2011), v. 3, Définition XIX.1.6.1.

- ^ Milne (2017), Proposition 21.60.

- ^ Milne. Linear Algebraic Groups (PDF). pp. 381–394.

- ^ Conrad (2014), after Proposition 5.1.17.

- ^ Borel (1991), 18.2(i).

- ^ Milne (2017), Theorem 22.42.

- ^ Milne (2017), Corollary 22.43.

- ^ Demazure & Gabriel (1970), Théorème IV.3.3.6.

- ^ Milne (2017), Theorem 12.12.

- ^ a b Milne (2017), Theorem 21.11.

- ^ Milne (2017), Corollary 21.12.

- ^ Milne (2017), Proposition 17.53.

- ^ Borel (1991), Proposition 21.12.

- ^ Chevalley (2005); Springer (1998), 9.6.2 and 10.1.1.

- ^ Milne (2017), Theorems 23.25 and 23.55.

- ^ Milne (2017), Corollary 23.47.

- ^ SGA 3 (2011), v. 3, Théorème XXV.1.1; Conrad (2014), Theorems 6.1.16 and 6.1.17.

- ^ Springer (1979), section 5.1.

- ^ Milne (2017), Theorem 22.2.

- ^ Jantzen (2003), Proposition II.4.5 and Corollary II.5.11.

- ^ Jantzen (2003), section II.8.22.

- ^ Riche & Williamson (2018), section 1.8.

- ^ a b c d Borel (1991), section 23.4.

- ^ Borel (1991), section 23.2.

- ^ Borel & Tits (1971), Corollaire 3.8.

- ^ Platonov & Rapinchuk (1994), Theorem 3.1.

- ^ Borel (1991), Theorem 20.9(i).

- ^ Steinberg (2016), Theorem 8.

- ^ Steinberg (2016), Theorem 30.

- ^ Tits (1964), Main Theorem; Gille (2009), Introduction.

- ^ Tits (1964), section 1.2.

- ^ Gille (2009), Théorème 6.1.

- ^ Platonov & Rapinchuk (1994), section 9.1.

- ^ Steinberg (1965), Theorem 1.9.

- ^ Platonov & Rapinchuk (1994), Theorem 6.6.

- ^ Platonov & Rapinchuk (1994), section 6.8.

- ^ Platonov & Rapinchuk (1994), Theorem 6.4.

References

[edit]- Borel, Armand (1991) [1969], Linear Algebraic Groups, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 126 (2nd ed.), New York: Springer Nature, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0941-6, ISBN 0-387-97370-2, MR 1102012

- Borel, Armand; Tits, Jacques (1971), "Éléments unipotents et sous-groupes paraboliques de groupes réductifs. I.", Inventiones Mathematicae, 12 (2): 95–104, Bibcode:1971InMat..12...95B, doi:10.1007/BF01404653, MR 0294349, S2CID 119837998

- Chevalley, Claude (2005) [1958], Cartier, P. (ed.), Classification des groupes algébriques semi-simples, Collected Works, Vol. 3, Springer Nature, ISBN 3-540-23031-9, MR 2124841

- Conrad, Brian (2014), "Reductive group schemes" (PDF), Autour des schémas en groupes, vol. 1, Paris: Société Mathématique de France, pp. 93–444, ISBN 978-2-85629-794-0, MR 3309122

- Demazure, Michel; Gabriel, Pierre (1970), Groupes algébriques. Tome I: Géométrie algébrique, généralités, groupes commutatifs, Paris: Masson, ISBN 978-2225616662, MR 0302656

- Demazure, M.; Grothendieck, A. (2011) [1970]. Gille, P.; Polo, P. (eds.). Schémas en groupes (SGA 3), I: Propriétés générales des schémas en groupes. Société Mathématique de France. ISBN 978-2-85629-323-2. MR 2867621. Revised and annotated edition of the 1970 original.

- Demazure, M.; Grothendieck, A. (1970). Groupes de Type Multiplicatif, et Structure des Schémas en Groupes Généraux. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. Vol. 152. Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/BFb0059005. ISBN 978-3540051800. MR 0274459.

- Demazure, M.; Grothendieck, A. (2011) [1970]. Gille, P.; Polo, P. (eds.). Schémas en groupes (SGA 3), III: Structure des schémas en groupes réductifs. Société Mathématique de France. ISBN 978-2-85629-324-9. MR 2867622. Revised and annotated edition of the 1970 original.

- Gille, Philippe (2009), "Le problème de Kneser–Tits" (PDF), Séminaire Bourbaki. Vol. 2007/2008, Astérisque, vol. 326, Société Mathématique de France, pp. 39–81, ISBN 978-285629-269-3, MR 2605318

- Jantzen, Jens Carsten (2003) [1987], Representations of Algebraic Groups (2nd ed.), American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-3527-2, MR 2015057

- Milne, J. S. (2017), Algebraic Groups: The Theory of Group Schemes of Finite Type over a Field, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/9781316711736, ISBN 978-1107167483, MR 3729270

- Platonov, Vladimir; Rapinchuk, Andrei (1994), Algebraic Groups and Number Theory, Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-558180-7, MR 1278263

- V.L. Popov (2001) [1994], "Reductive group", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- Riche, Simon; Williamson, Geordie (2018), Tilting Modules and the p-Canonical Basis, Astérisque, vol. 397, Société Mathématique de France, arXiv:1512.08296, Bibcode:2015arXiv151208296R, ISBN 978-2-85629-880-0

- Springer, Tonny A. (1979), "Reductive groups", Automorphic Forms, Representations, and L-functions, vol. 1, American Mathematical Society, pp. 3–27, ISBN 0-8218-3347-2, MR 0546587

- Springer, Tonny A. (1998), Linear Algebraic Groups, Progress in Mathematics, vol. 9 (2nd ed.), Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston, doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4840-4, ISBN 978-0-8176-4021-7, MR 1642713

- Steinberg, Robert (1965), "Regular elements of semisimple algebraic groups", Publications Mathématiques de l'IHÉS, 25: 49–80, doi:10.1007/bf02684397, MR 0180554, S2CID 55638217

- Steinberg, Robert (2016) [1968], Lectures on Chevalley Groups, University Lecture Series, vol. 66, American Mathematical Society, doi:10.1090/ulect/066, ISBN 978-1-4704-3105-1, MR 3616493

- Tits, Jacques (1964), "Algebraic and abstract simple groups", Annals of Mathematics, 80 (2): 313–329, doi:10.2307/1970394, JSTOR 1970394, MR 0164968

External links

[edit]- Demazure, M.; Grothendieck, A., Gille, P.; Polo, P. (eds.), Schémas en groupes (SGA 3), II: Groupes de type multiplicatif, et structure des schémas en groupes généraux Revised and annotated edition of the 1970 original.

Reductive group

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Basic Concepts

Definition via unipotent radical

Over an arbitrary field , a linear algebraic group is reductive if its geometric unipotent radical (after base change to the algebraic closure ) is trivial. Over an algebraically closed field , this simplifies to the unipotent radical being trivial, that is, .[4] This condition ensures that contains no nontrivial connected normal unipotent subgroups, distinguishing it from more general solvable or unipotent groups.[4] The unipotent radical is the unique maximal connected normal unipotent subgroup of .[4] A subgroup is unipotent if every one of its elements is unipotent. An element is unipotent if, in every rational representation, all eigenvalues of the image of are 1 (or equivalently, via Jordan-Chevalley decomposition, equals its unipotent part).[4] Over fields of characteristic zero, unipotent elements arise from the Jordan decomposition of elements in the Lie algebra , where every decomposes uniquely as with semisimple, nilpotent, and ; the unipotent radical then corresponds to the case where the nilpotent radical —the maximal nilpotent ideal of —is zero.[4] In general characteristics, the connection persists via the Lie algebra, with having Lie algebra equal to the nilradical of .[5] This definition originates in the foundational work of Claude Chevalley on algebraic groups during the 1950s, particularly in his seminar notes where he developed the structure theory linking Lie algebras to algebraic groups over arbitrary fields.[5] Reductive groups are smooth varieties of finite type over , and a key structural theorem states that every algebraic group admits a Levi decomposition , where is a reductive subgroup serving as the Levi factor.[4] This decomposition highlights how reductive groups capture the "nonsolvable" core of any algebraic group.[4]Equivalent characterizations

A linear algebraic group over a field of characteristic zero is reductive if and only if every finite-dimensional rational representation of is completely reducible, meaning that for every such representation on a vector space , every -invariant subspace has a -invariant complement, or equivalently, there are no infinite ascending chains of proper -invariant subspaces.[4][2] This representation-theoretic characterization highlights the absence of non-trivial extensions in the category of rational representations, distinguishing reductive groups from those with unipotent radicals that induce indecomposable representations. An equivalent criterion, often attributed to foundational work in the structure theory of algebraic groups, states that is reductive if and only if, for every faithful rational representation , the unipotent radical of the Zariski closure of the image is trivial.[4] This condition ensures that no non-trivial unipotent normal subgroups arise in faithful embeddings, directly tying back to the triviality of the unipotent radical of itself. In the presence of a maximal torus , the Lie algebra admits a weight space decomposition , where is the toral part, the are the root spaces (one-dimensional over algebraically closed fields), and is the set of roots; is reductive precisely when this decomposition holds with no non-zero nilpotent ideals in .[4][2] Such ideals would correspond to unipotent structure not captured by the semisimple and toral components. Reductive groups are precisely the central extensions of semisimple groups by tori: for a connected reductive , there exists a central torus and a semisimple group (the derived subgroup) such that fits in an exact sequence , with for some .[4][2] Cohomologically, over fields of characteristic zero, is reductive if and only if for every finite-dimensional rational -module , as this vanishing implies the absence of non-trivial extensions and thus complete reducibility of representations.[4]Simple and semisimple reductive groups

In the context of algebraic groups over an algebraically closed field of characteristic zero, a connected reductive group is called semisimple if its center is finite, or equivalently, if the derived subgroup coincides with and the maximal central torus is trivial.[6][7] This condition ensures that has no nontrivial unipotent normal subgroups and no positive-dimensional central torus, distinguishing it from more general reductive groups that may include a nontrivial torus in their center.[6] Semisimple groups thus capture the "non-abelian core" of reductive groups, where the structure is determined entirely by semisimple components without abelian extensions.[7] A semisimple group is simple if it has no nontrivial proper connected normal algebraic subgroups.[6] In this case, is indecomposable in the sense that its root system is irreducible, providing a direct correspondence between simple algebraic groups and irreducible root systems.[7] Every semisimple group admits a central isogeny decomposition into a product of simple factors, reflecting its structure as a direct product up to finite central kernels.[6] Conversely, reductive groups are central extensions of semisimple groups by tori, where the torus accounts for any abelian central factors.[7] Semisimple groups possess the property that they admit no nontrivial algebraic characters, meaning the homomorphism group is trivial, as their trivial center prevents any surjective maps onto the multiplicative group.[6] For the associated Lie algebra of a semisimple group, the commutator ideal and the center , emphasizing the perfect and centerless nature of the algebra.[6] The classification of simple algebraic groups over algebraically closed fields traces back to the foundational work of Killing and Cartan in the early 20th century on root systems and Lie algebras, later extended by Chevalley to algebraic groups.[6]Split reductive groups

A reductive algebraic group over a field is called split if it admits a maximal torus that is split over , meaning for some positive integer , and such that the root system associated to is defined over . For a split torus , the character group is a free -module of rank , and the induced Galois action of on is trivial, so that as -vector spaces with trivial action.[4][2] Equivalently, is split if and only if it possesses a Borel subgroup defined over , which contains a split maximal torus and whose unipotent radical is generated by root groups corresponding to a set of positive roots in . Split reductive groups are maximally compatible with the base field in the sense that their structure— including maximal tori, root systems, and Borel subgroups—can be described entirely over without extension.[4][2] These groups provide the standard models for the classification of reductive groups over arbitrary fields, as every reductive group over becomes split after base change to an algebraic closure . Non-split reductive groups arise as Galois twists of split ones, parametrized by elements of the cohomology set , where is the split form. Split simple reductive groups, such as or , serve as the basic building blocks for decomposing general split reductive groups into direct products of such simples times a central torus.[4][2]Examples

Classical reductive groups

The classical reductive groups are fundamental examples of reductive algebraic groups over a field , typically realized as closed subgroups of the general linear group that preserve specific bilinear or quadratic forms on the vector space or . These groups illustrate the abstract definition of reductivity through concrete matrix descriptions, where the unipotent radical is explicitly trivial, and they possess maximal tori that split over suitable extensions of . Their structures highlight the interplay between semisimple and toroidal components, with the former dominating in non-abelian cases. The general linear group consists of all invertible matrices with entries in . It is reductive, as its unipotent radical is trivial; this follows from the explicit observation that any unipotent normal subgroup must centralize and hence consist solely of the identity element, since unipotent scalars beyond the identity do not exist in . The dimension of is , matching that of its Lie algebra , the space of all matrices over . A maximal torus in is the diagonal subgroup, isomorphic to . The special linear group is the closed subgroup of defined by matrices of determinant 1. For , is semisimple, with center isomorphic to the finite group of -th roots of unity in (assuming does not divide ); its unipotent radical is trivial, verified by the same centralization argument as for , combined with the derived group structure . The Lie algebra consists of all trace-zero matrices over , and satisfies , confirming the semisimplicity at the infinitesimal level; its dimension is . A maximal torus in is the subgroup of diagonal matrices with product of entries equal to 1, a hypersurface in the torus of . The orthogonal groups and preserve a non-degenerate symmetric bilinear form (or equivalently, a quadratic form ) on the vector space . Specifically, , where is the Gram matrix of the form, and is the kernel of the determinant map . Both are reductive, with trivial unipotent radical for non-degenerate , as explicit computation shows no non-trivial unipotent elements normalize the form while being normal in the group; this holds particularly for split forms where the Witt index is maximal. A maximal split torus in these groups is isomorphic to , arising from orthogonal decompositions of the space into hyperbolic planes paired with possible anisotropic factors. For even , the root system is of type ; for odd , it is of type . The symplectic group (also denoted in some conventions) is the closed subgroup of preserving a non-degenerate alternating bilinear form on , given explicitly by , where is the standard skew-symmetric matrix with 1's on the anti-diagonal blocks. It is semisimple, with trivial unipotent radical verified by direct computation: any unipotent normal subgroup would preserve and centralize the group, but no such non-trivial elements exist due to the form's non-degeneracy. The dimension of is , and a maximal torus is the diagonal subgroup isomorphic to , acting via pairs on the standard symplectic basis. Its root system is of type . In each case, the triviality of the unipotent radical is confirmed via explicit matrix computations over algebraically closed fields, where semisimple elements diagonalize and unipotent ones Jordan-form, revealing no non-trivial normal unipotent subgroups compatible with the preserved forms. These groups often contain tori as central components in their Levi decompositions, underscoring their reductive nature.Tori as reductive groups

A torus in the context of algebraic groups over a field is defined as a connected reductive group that is isomorphic to for some integer , where denotes the multiplicative group . Over an algebraically closed field, every torus is split and thus isomorphic to . Split tori exist over any base field and serve as the abelian building blocks within more general reductive groups.[4][8][5] In a connected reductive group , a maximal torus is a torus that is not properly contained in any larger torus, and all such maximal tori are conjugate under the action of . The dimension of any maximal torus equals the rank of , which is invariant across conjugates. For a maximal torus in a semisimple reductive group, the centralizer coincides with itself, reflecting the absence of nontrivial central elements beyond the torus. Split maximal tori are conjugate via elements of .[4][8][5] Tori play a pivotal role in the structure of reductive groups, as every connected reductive group is generated by a maximal torus together with unipotent subgroups, such as root groups in the semisimple case; notably, the unipotent radical of a torus is trivial, underscoring its reductive purity. The character group of a split torus , defined as , is a free -module isomorphic to , providing a lattice that encodes the group's representations and diagonalizability.[4][8][5]Non-examples and associated reductive groups

Unipotent algebraic groups serve as fundamental non-examples of reductive groups, as their unipotent radical coincides with the group itself, rendering it nontrivial unless the group is trivial.[9] A prototypical instance is the subgroup of consisting of upper triangular matrices with 1's on the diagonal; this group is unipotent and hence non-reductive, with every element satisfying for the identity matrix .[9] Borel subgroups provide another class of non-reductive groups. In , the standard Borel subgroup comprises all upper triangular matrices, which is solvable but not reductive due to its nontrivial unipotent radical .[9] For any linear algebraic group , the quotient is reductive and termed the reductive quotient, effectively isolating the reductive structure by modding out the unipotent contributions.[10] In the specific case of the Borel subgroup in , the reductive quotient is isomorphic to the maximal torus of diagonal matrices, illustrating how the quotient captures the toral component.[9] More generally, connected solvable algebraic groups admit a Levi decomposition , where the Levi subgroup is reductive—often a torus—and serves as a reductive complement to the unipotent radical.[11] This decomposition underscores that the reductive quotient encodes the semisimple and central toral elements of modulo its unipotent part, providing a canonical path to reductivity.[10]Structure and Subgroups

Root systems

In a reductive algebraic group defined over an algebraically closed field, with a maximal torus , the roots are the nontrivial characters such that the root group , the unique connected unipotent subgroup of that is normalized by and on which acts via the character , and which is isomorphic to the additive group , is nontrivial (i.e., ).[4] These roots form the set , which encodes the structure of relative to .[8] The Lie algebra of decomposes under the adjoint action of as , where is the Lie algebra of , and each root space is the 1-dimensional eigenspace on which acts via the character .[4] Moreover, , and the root groups are isomorphic to the additive group .[12] The set of roots forms a reduced root system in the real vector space , meaning that is finite, spans , contains no nonzero scalar multiples of its elements except for each , and is invariant under reflections across hyperplanes orthogonal to roots, where is the coroot.[4] Additionally, is crystallographic, lying in a -lattice (the character lattice ) such that the reflections preserve this lattice and the inner products are integers for all roots .[8] A choice of Borel subgroup containing induces a notion of positive roots , consisting of those for which , the Lie algebra of the unipotent radical of .[4] This set admits a unique basis of simple roots such that every positive root is a nonnegative integer combination of elements of , and .[12] The Weyl group is the finite group generated by the reflections for , acting faithfully on and on .[4] It normalizes and plays a key role in the symmetry of the root system.[8] For root spaces, the Lie bracket satisfies if , and otherwise ; more precisely, for and , we have where is a structure constant (possibly zero).[4] A key property is the existence of root strings: for , the set forms a finite string of consecutive integer multiples, unbroken except possibly at the ends, with length determined by the integer .[4] This reflects the crystallographic nature and ensures the integrality of the root system.[8]Parabolic subgroups

In the theory of reductive algebraic groups, a parabolic subgroup of a connected reductive group over an algebraically closed field is defined as a closed connected subgroup that contains a Borel subgroup of .[13] Equivalently, is the stabilizer in of a nontrivial partial flag in some finite-dimensional rational representation of , where the partial flag consists of a chain of -stable subspaces.[13] This geometric characterization underscores the role of parabolic subgroups in the study of flag varieties , which are projective algebraic varieties.[13] Every parabolic subgroup admits a unique Levi decomposition , where is a reductive Levi subgroup (centralizing a Levi torus) and is the unipotent radical of , a normal connected unipotent subgroup.[13] The Levi subgroup intersects every Borel subgroup of in a maximal torus of , and is generated by the root groups corresponding to a certain set of positive roots relative to that torus.[13] This semidirect product structure is canonical up to conjugation within , and it generalizes the Borel case where (a maximal torus) and is the unipotent radical of the Borel.[13] Parabolic subgroups are parametrized by the root system of : fixing a Borel with associated set of simple roots, each parabolic containing corresponds bijectively to a subset .[13] The Levi subgroup has root system consisting of the roots spanned by , while the unipotent radical is generated by the root groups for positive roots in , where denotes the roots generated by and are the positive roots for .[13] Thus, the roots associated to are .[13] This correspondence relies on the root datum and ensures that all parabolics containing a fixed Borel are standard, with conjugates filling out the full set of parabolics in .[13] The minimal parabolic subgroups are precisely the Borel subgroups, which stabilize complete flags and correspond to .[13] Maximal parabolic subgroups, on the other hand, arise when omits exactly one simple root from , stabilizing flags of codimension equal to the multiplicity of that root; for example, in the standard representation of , a maximal parabolic stabilizes a line (projective space stabilizer) or a hyperplane.[13] For each parabolic , there exists a unique opposite parabolic such that (the Levi subgroup) and the unipotent radicals and generate their product as a direct product, with .[13] This pair facilitates the Bruhat decomposition relative to parabolics: , where is the Weyl group of (or more precisely, a set of coset representatives for , with the Weyl group of ), providing a cell decomposition of the flag variety into -orbits.[13] The opposite parabolic corresponds to replacing with in the root description, ensuring symmetry in the theory.[13]Borel subgroups

In the theory of reductive algebraic groups, a Borel subgroup of a connected reductive group over a field is defined as a maximal connected solvable subgroup.[13] Equivalently, it is a minimal parabolic subgroup, meaning it is a proper parabolic subgroup that does not properly contain any other parabolic subgroup.[13] These subgroups play a central role in the structure theory of reductive groups, as they encode choices of positive roots relative to a maximal torus. All Borel subgroups of are conjugate under the action of , provided is algebraically closed or is quasi-split over .[13] For a fixed maximal torus , the Weyl group acts simply and transitively by conjugation on the set of Borel subgroups containing .[13] Every Borel subgroup contains a unique maximal torus up to conjugation within , and it admits a Levi decomposition , where is a maximal torus and is the unipotent radical of , a connected unipotent subgroup normal in .[13] The unipotent radical is generated by the root subgroups corresponding to a system of positive roots in the root system of with respect to , and explicitly, .[13] In the case of a split reductive group over , there exist Borel subgroups defined over , and the positive roots can be chosen compatibly with the split torus.[13] This splitting property ensures that the structure of aligns with the base field, facilitating computations in number theory and representation theory. A fundamental application of Borel subgroups is the Bruhat decomposition, which expresses as a disjoint union of double cosets: , where is the Weyl group.[13] Each double coset is an affine space of dimension equal to the length of in , and this decomposition parametrizes the geometry of the flag variety .[13] The choice of determines the Borel uniquely among those containing , establishing a bijection between Borel subgroups containing and systems of positive roots.Classification

Classification of split reductive groups

Split reductive groups over an algebraically closed field are classified up to isomorphism by their rank and the type of their root system, which determines the Weyl group and the structure of the group.[4] The root system is a finite reduced root system in the character lattice of a maximal split torus, and two such groups are isomorphic if and only if their root data—consisting of the character lattice, the root system, and the pairing with coroots—are isomorphic.[4] This classification extends the earlier work on semisimple Lie algebras to the group setting over arbitrary fields when the group is split.[14] Simple split reductive groups correspond precisely to irreducible root systems, which fall into four infinite families of classical types—A (), B (), C (), and D ()—along with five exceptional types: E, E, E, F, and G.[4] Each type determines the group uniquely up to isogeny, with examples including SL for type A, Spin for B, Sp for C, and Spin for D, while the exceptional groups arise from structures like octonions (G) or Jordan algebras (F, E series).[4] Semisimple split reductive groups are then direct products of simple ones, corresponding to decomposable root systems as orthogonal direct sums of irreducibles.[4] In the general reductive case, the group is a central extension of a semisimple group by a torus, where the torus is the connected component of the center, and the semisimple quotient is determined by the root system as above.[4] Isogeny classes within each type are parameterized by finite central subgroups, leading to simply connected forms (universal covers) and adjoint forms (quotients by the full center), with intermediate isogenies corresponding to subgroups of the fundamental group of the root system.[4] For instance, in type A, the simply connected form is SL and the adjoint is PGL, connected by the determinant map.[4] The full classification of split forms over arbitrary fields was established by Borel and Tits in the 1960s, building on Chevalley's earlier work for algebraically closed fields and extending it via the existence of split maximal tori and root data over the base field.[14] For a simply connected semisimple split reductive group with maximal torus , the dimension is given by , where is the set of positive roots relative to a choice of Borel subgroup containing .[4] This formula reflects the decomposition of the Lie algebra into the Cartan subalgebra (dimension ) and the root spaces (two per positive root).[4]Dynkin diagrams and root data

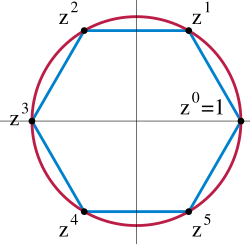

Dynkin diagrams provide a graphical classification of the root systems associated to split reductive groups over algebraically closed fields of characteristic zero. They encode the structure of a basis of simple roots for the root system of the group, where is the semisimple rank. Each diagram consists of nodes representing the simple roots, connected by edges that indicate the angles between them: a single edge denotes an angle of 120 degrees, a double edge 135 degrees, and a triple edge 150 degrees, with arrows pointing from longer to shorter roots when lengths differ.[15] The irreducible Dynkin diagrams, corresponding to simple root systems, fall into classical and exceptional types. The classical series include:- (for ): A linear chain of nodes connected by single edges, associated to the special linear group .

- (for ): A linear chain of single edges ending in a double edge with arrow pointing to the end node, reflecting short roots at the end, linked to odd orthogonal groups .

- (for ): A linear chain of nodes with the double edge between the first two nodes and the arrow pointing toward the first node (short root), corresponding to symplectic groups .

- (for ): A linear chain of nodes connected by single edges, with the th node forking into two additional nodes connected by single edges, tied to even orthogonal groups .

- : Extended branched structures with 6, 7, and 8 nodes, respectively, featuring a linear chain with an additional branch of two or three nodes.

- : Four nodes with single, double, and single edges in sequence, including an arrow.

- : Two nodes connected by a triple edge with an arrow.[16][17]