Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Retinal nerve fiber layer

View on Wikipedia

| Retinal nerve fiber layer | |

|---|---|

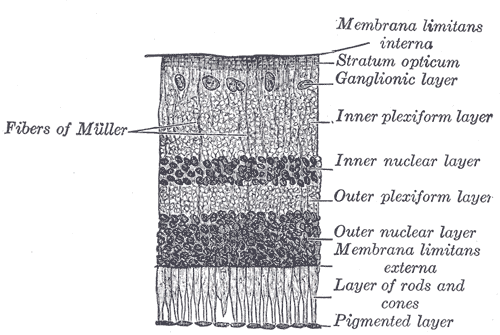

Section of retina. (Stratum opticum labeled at right, second from the top.) | |

Plan of retinal neurons. (Stratum opticum labeled at left, second from the top.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | stratum neurofibrarum retinae |

| TA98 | A15.2.04.017 |

| FMA | 58688 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) or nerve fiber layer, stratum opticum, is part of the anatomy of the eye.

Physical structure

[edit]The RNFL formed by the expansion of the fibers of the optic nerve; it is thickest near the optic disc, gradually diminishing toward the ora serrata.

As the nerve fibers pass through the lamina cribrosa sclerae they lose their medullary sheaths and are continued onward through the choroid and retina as simple axis-cylinders.

When they reach the internal surface of the retina they radiate from their point of entrance over this surface grouped in bundles, and in many places arranged in plexuses.

Most of the fibers are centripetal, and are the direct continuations of the axis-cylinder processes of the cells of the ganglionic layer, but a few of them are centrifugal and ramify in the inner plexiform and inner nuclear layers, where they end in enlarged extremities.

Measurement

[edit]RNFL measurement can be made by Optical coherence tomography.[1]

Relation with diseases

[edit]RNFL reduction

[edit]Retinitis pigmentosa

[edit]Patients with retinitis pigmentosa have abnormal thinning of the RNFL which correlates with the severity of the disease.[2] However the thickness of the RNFL also decreases with age and not visual acuity.[3] The sparing of this layer is important in the treatment of the disease as it is the basis for connecting retinal prostheses to the optic nerve, or implanting stem cells that could regenerate the lost photoreceptors.

Asymmetric RNFL

[edit]RNFL asymmetry is the difference between the RNFL of the left and right eyes. In healthy patients, one study (2008, n=109) found asymmetry to be typically between 0-8μm, but occasionally higher, with average asymmetry of c.3μm at age 25 rising to 5μm at age 60.[4] A 2011 study (n=284) concluded that RNFL asymmetry exceeding 9μm may be considered statistically significant and may be indicative of early glaucomatous damage.[5] A 2023 study of 4034 children found mean RNFL of 106μm with SD of 9.4μm.[6]

Optic neuritis

[edit]RNFL asymmetry has been proposed as a strong indicator of optic neuritis,[7][8] with one small study proposing that asymmetry of 5–6μm was "a robust structural threshold for identifying the presence of a unilateral optic nerve lesion in MS."[9] Optic neuritis is often associated with multiple sclerosis, and RNFL data may indicate the pace of future development of the MS.[10][11]

Glaucoma

[edit]RNFL asymmetry may be produced by glaucoma.[12][13][14][15] Glaucoma is a lead cause of irreversible blindness. Resesrch in RNFL and optic nerve head (ONH) abnormalities may enable early detection and diagnosis of glaucoma.[2]

Fibromyalgia

[edit]One small study found that fibromyalgia patients had decreased RNFL thickness[16] but another found no difference.[17]

Correlation with ethnicity

[edit]Other factors affecting RNFL

[edit]Some processes can excite RNFL apoptosis. Harmful situations which can damage RNFL include high intraocular pressure, high fluctuation on phase of intraocular pressure, inflammation, vascular disease and any kind of hypoxia. Gede Pardianto (2009) reported 6 cases of RNFL thickness change after the procedures of phacoemulsification.[20] Sudden intraocular fluctuation in any kind of intraocular surgeries maybe harmful to RNFL in accordance with mechanical stress on sudden compression and also ischemic effect of micro emboly as the result of the sudden decompression that may generate micro bubble that can clog micro vessels.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Optic Nerve and Retinal Nerve Fiber Imaging - EyeWiki". eyewiki.org.[unreliable medical source?]

- ^ a b Desissaire S, Pollreisz A, Sedova A, Hajdu D, Datlinger F, Steiner S, et al. (October 2020). "Analysis of retinal nerve fiber layer birefringence in patients with glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy by polarization sensitive OCT". Biomedical Optics Express. 11 (10): 5488–5505. doi:10.1364/BOE.402475. PMC 7587266. PMID 33149966.

- ^ Oishi A, Otani A, Sasahara M, Kurimoto M, Nakamura H, Kojima H, et al. (March 2009). "Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in patients with retinitis pigmentosa". Eye. 23 (3): 561–6. doi:10.1038/eye.2008.63. PMID 18344951.

- ^ Budenz DL (2008). "Symmetry Between the Right and Left Eyes of the Normal Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Measured with Optical Coherence Tomography (An AOS Thesis)". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 106: 252–275. PMC 2646446. PMID 19277241.

- ^ Mwanza JC, Durbin MK, Budenz DL (March 2011). "Interocular Symmetry in Peripapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness Measured With the Cirrus HD-OCT in Healthy Eyes". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 151 (3): 514–521.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2010.09.015. PMC 5457794. PMID 21236402.

- ^ Zhang XJ, Wang YM, Jue Z, Chan HN, Lau YH, Zhang W, et al. (2023). "Interocular Symmetry in Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Children: The Hong Kong Children Eye Study". Ophthalmology and Therapy. 12 (6): 3373–3382. doi:10.1007/s40123-023-00825-7. PMC 10640485. PMID 37851163.

- ^ Jiang H, Delgado S, Wang J (2021). "Advances in ophthalmic structural and functional measures in multiple sclerosis: do the potential ocular biomarkers meet the unmet needs?". Current Opinion in Neurology. 34 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000897. PMC 7856092. PMID 33278142.

- ^ Nij Bijvank J, Uitdehaag BM, Petzold A (2021). "Short report: Retinal inter-eye difference and atrophy progression in multiple sclerosis diagnostics". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 93 (2): 216–219. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2021-327468. PMC 8785044. PMID 34764152.

- ^ Nolan RC, Galetta SL, Frohman TC, Frohman EM, Calabresi PA, Castrillo-Viguera C, et al. (December 2018). "Optimal Intereye Difference Thresholds in Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness for Predicting a Unilateral Optic Nerve Lesion in Multiple Sclerosis". Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 38 (4): 451–458. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000629. PMC 8845082. PMID 29384802.

- ^ Bsteh G, Hegen H, Altmann P, Auer M, Berek K, Pauli FD, et al. (October 19, 2020). "Retinal layer thinning is reflecting disability progression independent of relapse activity in multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis Journal: Experimental, Translational and Clinical. 6 (4) 2055217320966344. doi:10.1177/2055217320966344. PMC 7604994. PMID 33194221.

- ^ Martinez-Lapiscina EH, Arnow S, Wilson JA, Saidha S, Preiningerova JL, Oberwahrenbrock T, et al. (May 2016). "Retinal thickness measured with optical coherence tomography and risk of disability worsening in multiple sclerosis: a cohort study". The Lancet. Neurology. 15 (6): 574–584. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00068-5. PMID 27011339.

- ^ Rodríguez-Robles F, Verdú-Monedero R, Berenguer-Vidal R, Morales-Sánchez J, Sellés-Navarro I (14 May 2023). "Analysis of the Asymmetry between Both Eyes in Early Diagnosis of Glaucoma Combining Features Extracted from Retinal Images and OCTs into Classification Models". Sensors. 23 (10): 4737. Bibcode:2023Senso..23.4737R. doi:10.3390/s23104737. PMC 10220946. PMID 37430650.

- ^ Choplin NT, Craven ER, Reus NJ, Lemij HG, Barnebey H (2015). "Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer (RNFL) Photography and Computer Analysis". Glaucoma. pp. 244–260. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-5193-7.00021-2. ISBN 978-0-7020-5193-7.

- ^ Berenguer-Vidal R, Verdú-Monedero R, Morales-Sánchez J, Sellés-Navarro I, Kovalyk O (2022). "Analysis of the Asymmetry in RNFL Thickness Using Spectralis OCT Measurements in Healthy and Glaucoma Patients". Artificial Intelligence in Neuroscience: Affective Analysis and Health Applications. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 13258. pp. 507–515. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-06242-1_50. ISBN 978-3-031-06241-4.

- ^ "RNFL Analysis in the Diagnosis of Glaucoma". Glaucoma Today.

- ^ Garcia-Martin E, Tello A, Vilades E, Perez-Velilla J, Cordon B, Fernandez-Velasco D, et al. (February 26, 2022). "Diagnostic Ability and Capacity of Optical Coherence Tomography-Angiography to Detect Retinal and Vascular Changes in Patients with Fibromyalgia". Journal of Ophthalmology. 2022 (1) 3946017. doi:10.1155/2022/3946017. PMC 9440831. PMID 36065284.

- ^ Talu Erten P, Bilgin S (June 2024). "Assessment of ophthalmic vascular changes in fibromyalgia patients using optical coherence tomography angiography: is there a real pathology?". JFO Open Ophthalmology. 6 100057. doi:10.1016/j.jfop.2023.100057.

- ^ Nousome D, McKean-Cowdin R, Richter GM, Burkemper B, Torres M, Varma R, et al. (2020). "Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Healthy Eyes of African, Chinese, and Latino Americans: A Population-based Multiethnic Study". Ophthalmology. 128 (7): 1005–1015. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.11.015. PMC 8128930. PMID 33217471.

- ^ Heidary F, Gharebaghi R, Wan Hitam WH, Shatriah I (September 2010). "Nerve fiber layer thickness". Ophthalmology. 117 (9): 1861–1862. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.05.024. PMID 20816254.

- ^ Pardianto G (2009). "Mastering phacoemulsification in Mimbar Ilmiah". Oftalmologi Indonesia. 10: 26.

- ^ Pardianto G, Moeloek N, Reveny J, Wage S, Satari I, Sembiring R, et al. (2013). "Retinal thickness changes after phacoemulsification". Clinical Ophthalmology. 7. Auckland, N.Z.: 2207–14. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S53223. PMC 3821754. PMID 24235812.

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1015 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1015 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

[edit]- Histology image: 07902loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

Retinal nerve fiber layer

View on GrokipediaAnatomy and Development

Histological Structure

The retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) constitutes the innermost layer of the neurosensory retina, positioned immediately adjacent to the internal limiting membrane and the overlying vitreous humor.[3] This superficial location allows the RNFL to form the interface between the neural retina and the vitreous cavity, facilitating the convergence of visual signals toward the optic disc.[4] The primary cellular component of the RNFL consists of unmyelinated axons originating from retinal ganglion cells, which extend from the ganglion cell layer to the optic nerve head.[4] These axons are organized into parallel bundles that course across the inner retinal surface, supported structurally by processes of Müller glial cells that wrap and insulate the bundles, preventing mechanical damage and maintaining axonal integrity.[5] Additionally, retinal astrocytes, a specialized type of macroglia, envelop the axonal bundles, providing metabolic support, regulating ion homeostasis, and contributing to the extracellular matrix within the RNFL.[6] Together, these elements form a compact, organized tissue devoid of myelination, which distinguishes the RNFL from the myelinated optic nerve beyond the lamina cribrosa.[7] Regionally, the RNFL exhibits distinct organizational patterns adapted to the topographic distribution of retinal ganglion cell projections. In the superior and inferior quadrants, axons form prominent arcuate bundles that arch around the macula, creating a characteristic "hourglass" pattern that funnels fibers toward the optic disc.[8] Nasally, the papillomacular bundle predominates, comprising a denser aggregation of axons from ganglion cells near the macula that project directly to the optic nerve head, supporting high-acuity central vision.[9] These variations in bundling reflect the functional specialization of visual pathways, with arcuate bundles serving peripheral fields and the papillomacular bundle emphasizing foveal input.[10] The axons within the RNFL remain unmyelinated throughout their intra-retinal course, only acquiring myelin sheaths upon entering the optic nerve head at the lamina cribrosa, which optimizes signal conduction while minimizing retinal bulk.[7] In adults, the RNFL exhibits an average thickness of approximately 100-120 μm, with notable quadrant-specific differences: the superior and inferior regions are thicker (often exceeding 130 μm) compared to the thinner nasal and temporal quadrants, reflecting the higher axonal density in arcuate areas.[11][12][13]Embryological Development

The embryological development of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) begins with the differentiation of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) from retinal progenitor cells in the inner neuroblastic zone of the neural retina. In humans, RGC neurogenesis initiates around the 7th gestational week, marking the first neuronal cell type to emerge in the retina.[14] These cells rapidly extend axons toward the optic disc, with initial axonogenesis occurring before 10 weeks of gestation in the central retina.[15] By 8 weeks, axons begin populating the optic nerve, and extension continues progressively, reaching the chiasm by approximately 10-12 weeks.[16][17] Axonogenesis is precisely guided by molecular cues, including netrins and semaphorins, which direct RGC growth cones during pathfinding. Netrin-1, expressed at the optic nerve head, acts as a chemoattractant to facilitate axon exit from the retina, triggering local protein synthesis in growth cones within minutes via receptors like DCC.[18] Semaphorin 3A, conversely, promotes repulsion and growth cone collapse in distal regions, with responsiveness emerging as axons advance into the optic pathway; this involves cytoskeletal reorganization and endocytosis.[18] Concurrently, astroglial precursors invade the nascent RNFL from the optic nerve, establishing supportive networks essential for axon organization.[19] Müller cells, derived from retinal progenitors via Notch signaling and factors like Sox9, play a critical role in early RNFL assembly by providing structural support for axon bundling. During weeks 12-20 of gestation, their endfeet delimit and stabilize emerging axon bundles within the RNFL, contributing to layer thickening as the inner neuroblastic zone matures.[20] A well-defined RNFL is evident by 18 weeks, comprising about one-fourth of the inner zone thickness, with progressive expansion thereafter.[15] During this period, RGC axons undergo significant overproduction, peaking at approximately 3.7 million axons in the optic nerve around 16-17 weeks gestation, followed by elimination of about 70% (resulting in ~1.2 million axons by birth) through apoptotic processes that refine the RNFL's axonal composition.[17] RNFL maturation involves continued thickening that peaks postnatally, transitioning from a biphasic pattern around 38 weeks postmenstrual age, after which minor thinning occurs as the layer stabilizes.[21] Myelination of RGC axons commences in the late fetal period at the optic disc, progressing anteriorly from the lateral geniculate body but halting posterior to the lamina cribrosa near birth, ensuring the RNFL remains unmyelinated.[22] Recent studies emphasize that the development of retinal astroglia, including Müller cells and RNFL-specific astrocytes, is vital for RNFL structural integrity, as these cells integrate neuronal and vascular elements through VEGF-mediated patterning and mechanical support.[19]Function and Physiology

Role in Visual Signal Transmission

The retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) comprises the unmyelinated axons of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), which serve as the final output neurons of the retina, integrating and relaying processed visual information from upstream retinal circuits to the central nervous system.[23] These axons originate from RGC somata in the ganglion cell layer, course superficially through the retina in bundled arcuate trajectories, and converge at the optic disc to exit the eye as the optic nerve (cranial nerve II).[23] Upon leaving the eye, the optic nerve contains approximately 1.2 million axons that conduct action potentials toward the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus, passing through the optic chiasm where nasal fibers partially decussate and then continuing via the optic tract.[24] This pathway integration ensures the transmission of spatially organized visual signals from the retina to higher visual centers.[23] Within the RNFL, action potentials propagate along these unmyelinated axons at conduction velocities typically ranging from 0.5 to 1.7 m/s, enabling the relay of neural signals despite the absence of myelin sheaths in the intraretinal segment.[25] Myelination begins just posterior to the lamina cribrosa in the optic nerve head, accelerating conduction beyond the eye, but the RNFL's slower velocity contributes to the overall timing of visual processing.[26] Conduction velocities vary spatially across the RNFL, with peripheral axons propagating faster than foveal ones (up to three times higher) to compensate for longer paths and synchronize signals at the LGN.[25] Glial support is crucial for maintaining this transmission: astrocytes, primarily located in the RNFL, provide metabolic support to axons by regulating nutrient supply and waste removal, while also ensheathing blood vessels to stabilize the local microenvironment.[27] Complementarily, Müller cells span the retinal thickness, their processes interfacing with the RNFL to maintain ionic balance—particularly potassium homeostasis—during repetitive firing, preventing disruptions in signal propagation.[28] The RNFL's role is fundamentally important for conveying feature-specific visual data, such as contrast sensitivity, motion detection, and color opponency, encoded by distinct RGC subtypes whose axons form the layer.[23] This selective transmission preserves the fidelity of retinal computations, allowing the brain to reconstruct coherent visual scenes.[23] Damage to RNFL axons, such as from injury or degeneration, compromises this relay, resulting in reduced signal amplitude and desynchronized arrival times at the LGN, which manifests as visual field defects.[23]Normal Thickness Characteristics

The retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in healthy adults exhibits a mean global thickness ranging from 97 to 110 μm, reflecting the bundled unmyelinated axons of retinal ganglion cells that converge toward the optic disc.[29][13] This thickness varies by quadrant, following the ISNT rule (inferior > superior > nasal > temporal), with typical values of approximately 120 μm in the superior and inferior quadrants, 80 μm in the nasal quadrant, and 70 μm in the temporal quadrant.[30][11] Age-related thinning of the RNFL is a physiological process, with an annual reduction of 0.2-0.4 μm observed after age 20, accelerating to higher rates after age 50 due to progressive axonal loss.[31][32] In healthy individuals, inter-eye symmetry is high, with typical differences in average RNFL thickness less than 5-10 μm, supporting the use of bilateral comparisons in clinical assessments.[33][34] Minor diurnal fluctuations in RNFL thickness, on the order of 2-5 μm, occur in healthy eyes, primarily attributable to variations in intraocular pressure throughout the day.[35] Normative reference databases, such as those derived from large cohorts like the UK Biobank, provide age- and sex-adjusted percentiles for RNFL thickness, enabling percentile-based evaluations in populations exceeding 20,000 individuals.[36]| Quadrant | Approximate Normal Thickness (μm) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Superior | ~120 | Knighton et al., 2012 |

| Inferior | ~120 | Knighton et al., 2012 |

| Nasal | ~80 | Bendsen et al., 2017 |

| Temporal | ~70 | Bendsen et al., 2017 |