Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hyperbolic functions

View on Wikipedia

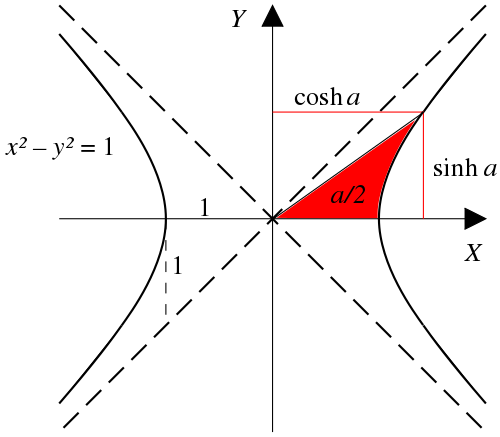

In mathematics, hyperbolic functions are analogues of the ordinary trigonometric functions, but defined using the hyperbola rather than the circle. Just as the points (cos t, sin t) form a circle with a unit radius, the points (cosh t, sinh t) form the right half of the unit hyperbola. Also, similarly to how the derivatives of sin(t) and cos(t) are cos(t) and –sin(t) respectively, the derivatives of sinh(t) and cosh(t) are cosh(t) and sinh(t) respectively.

Hyperbolic functions are used to express the angle of parallelism in hyperbolic geometry. They are used to express Lorentz boosts as hyperbolic rotations in special relativity. They also occur in the solutions of many linear differential equations (such as the equation defining a catenary), cubic equations, and Laplace's equation in Cartesian coordinates. Laplace's equations are important in many areas of physics, including electromagnetic theory, heat transfer, and fluid dynamics.

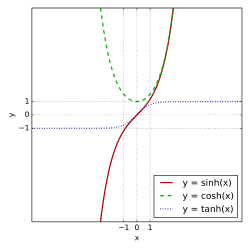

The basic hyperbolic functions are:[1]

- hyperbolic sine "sinh" (/ˈsɪŋ, ˈsɪntʃ, ˈʃaɪn/),[2]

- hyperbolic cosine "cosh" (/ˈkɒʃ, ˈkoʊʃ/),[3]

from which are derived:[4]

- hyperbolic tangent "tanh" (/ˈtæŋ, ˈtæntʃ, ˈθæn/),[5]

- hyperbolic cotangent "coth" (/ˈkɒθ, ˈkoʊθ/),[6][7]

- hyperbolic secant "sech" (/ˈsɛtʃ, ˈʃɛk/),[8]

- hyperbolic cosecant "csch" or "cosech" (/ˈkoʊsɛtʃ, ˈkoʊʃɛk/[3])

corresponding to the derived trigonometric functions.

The inverse hyperbolic functions are:

- inverse hyperbolic sine "arsinh" (also denoted "sinh−1", "asinh" or sometimes "arcsinh")[9][10][11]

- inverse hyperbolic cosine "arcosh" (also denoted "cosh−1", "acosh" or sometimes "arccosh")

- inverse hyperbolic tangent "artanh" (also denoted "tanh−1", "atanh" or sometimes "arctanh")

- inverse hyperbolic cotangent "arcoth" (also denoted "coth−1", "acoth" or sometimes "arccoth")

- inverse hyperbolic secant "arsech" (also denoted "sech−1", "asech" or sometimes "arcsech")

- inverse hyperbolic cosecant "arcsch" (also denoted "arcosech", "csch−1", "cosech−1","acsch", "acosech", or sometimes "arccsch" or "arccosech")

The hyperbolic functions take a real argument called a hyperbolic angle. The magnitude of a hyperbolic angle is the area of its hyperbolic sector to xy = 1. The hyperbolic functions may be defined in terms of the legs of a right triangle covering this sector.

In complex analysis, the hyperbolic functions arise when applying the ordinary sine and cosine functions to an imaginary angle. The hyperbolic sine and the hyperbolic cosine are entire functions. As a result, the other hyperbolic functions are meromorphic in the whole complex plane.

By Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem, the hyperbolic functions have a transcendental value for every non-zero algebraic value of the argument.[12]

History

[edit]The first known calculation of a hyperbolic trigonometry problem is attributed to Gerardus Mercator when issuing the Mercator map projection circa 1566. It requires tabulating solutions to a transcendental equation involving hyperbolic functions.[13]

The first to suggest a similarity between the sector of the circle and that of the hyperbola was Isaac Newton in his 1687 Principia Mathematica.[14]

Roger Cotes suggested to modify the trigonometric functions using the imaginary unit to obtain an oblate spheroid from a prolate one.[14]

Hyperbolic functions were formally introduced in 1757 by Vincenzo Riccati.[14][13][15] Riccati used Sc. and Cc. (sinus/cosinus circulare) to refer to circular functions and Sh. and Ch. (sinus/cosinus hyperbolico) to refer to hyperbolic functions.[14] As early as 1759, Daviet de Foncenex showed the interchangeability of the trigonometric and hyperbolic functions using the imaginary unit and extended de Moivre's formula to hyperbolic functions.[15][14]

During the 1760s, Johann Heinrich Lambert systematized the use functions and provided exponential expressions in various publications.[14][15] Lambert credited Riccati for the terminology and names of the functions, but altered the abbreviations to those used today.[15][16]

Notation

[edit]Definitions

[edit]

With hyperbolic angle u, the hyperbolic functions sinh and cosh can be defined with the exponential function eu.[1][4] In the figure .

Exponential definitions

[edit]

- Hyperbolic sine: the odd part of the exponential function, that is,

- Hyperbolic cosine: the even part of the exponential function, that is,

- Hyperbolic tangent:

- Hyperbolic cotangent: for x ≠ 0,

- Hyperbolic secant:

- Hyperbolic cosecant: for x ≠ 0,

Differential equation definitions

[edit]The hyperbolic functions may be defined as solutions of differential equations: The hyperbolic sine and cosine are the solution (s, c) of the system with the initial conditions The initial conditions make the solution unique; without them any pair of functions would be a solution.

sinh(x) and cosh(x) are also the unique solution of the equation f ″(x) = f (x), such that f (0) = 1, f ′(0) = 0 for the hyperbolic cosine, and f (0) = 0, f ′(0) = 1 for the hyperbolic sine.

Complex trigonometric definitions

[edit]Hyperbolic functions may also be deduced from trigonometric functions with complex arguments:

- Hyperbolic sine:[1]

- Hyperbolic cosine:[1]

- Hyperbolic tangent:

- Hyperbolic cotangent:

- Hyperbolic secant:

- Hyperbolic cosecant:

where i is the imaginary unit with i2 = −1.

The above definitions are related to the exponential definitions via Euler's formula (See § Hyperbolic functions for complex numbers below).

Characterizing properties

[edit]Hyperbolic cosine

[edit]It can be shown that the area under the curve of the hyperbolic cosine (over a finite interval) is always equal to the arc length corresponding to that interval:[17]

Hyperbolic tangent

[edit]The hyperbolic tangent is the (unique) solution to the differential equation f ′ = 1 − f 2, with f (0) = 0.[18][19]

Useful relations

[edit]The hyperbolic functions satisfy many identities, all of them similar in form to the trigonometric identities. In fact, Osborn's rule[20] (named after George Osborn) states that one can convert any trigonometric identity (up to but not including sinhs or implied sinhs of 4th degree) for , , or and into a hyperbolic identity, by:

- expanding it completely in terms of integral powers of sines and cosines,

- changing sine to sinh and cosine to cosh, and

- switching the sign of every term containing a product of two sinhs.

Odd and even functions:

Hence:

Thus, cosh x and sech x are even functions; the others are odd functions.

Hyperbolic sine and cosine satisfy:

which are analogous to Euler's formula, and

which is analogous to the Pythagorean trigonometric identity.

One also has

for the other functions.

Sums of arguments

[edit]particularly

Also:

Product formulas

[edit]

Subtraction formulas

[edit]

Also:[21]

Half argument formulas

[edit]

where sgn is the sign function.

If x ≠ 0, then[22]

Square formulas

[edit]

Inequalities

[edit]The following inequality is useful in statistics:[23]

It can be proved by comparing the Taylor series of the two functions term by term.

Inverse functions as logarithms

[edit]

Derivatives

[edit]

Second derivatives

[edit]Each of the functions sinh and cosh is equal to its second derivative, that is:

All functions with this property are linear combinations of sinh and cosh, in particular the exponential functions and .[24]

Standard integrals

[edit]

The following integrals can be proved using hyperbolic substitution:

where C is the constant of integration.

Taylor series expressions

[edit]It is possible to express explicitly the Taylor series at zero (or the Laurent series, if the function is not defined at zero) of the above functions.

This series is convergent for every complex value of x. Since the function sinh x is odd, only odd exponents for x occur in its Taylor series.

This series is convergent for every complex value of x. Since the function cosh x is even, only even exponents for x occur in its Taylor series.

The sum of the sinh and cosh series is the infinite series expression of the exponential function.

The following series are followed by a description of a subset of their domain of convergence, where the series is convergent and its sum equals the function.

where:

- is the nth Bernoulli number

- is the nth Euler number

Infinite products and continued fractions

[edit]The following expansions are valid in the whole complex plane:

Comparison with circular functions

[edit]

The hyperbolic functions represent an expansion of trigonometry beyond the circular functions. Both types depend on an argument, either circular angle or hyperbolic angle.

Since the area of a circular sector with radius r and angle u (in radians) is r2u/2, it will be equal to u when r = √2. In the diagram, such a circle is tangent to the hyperbola xy = 1 at (1, 1). The yellow sector depicts an area and angle magnitude. Similarly, the yellow and red regions together depict a hyperbolic sector with area corresponding to hyperbolic angle magnitude.

The legs of the two right triangles with hypotenuse on the ray defining the angles are of length √2 times the circular and hyperbolic functions.

The hyperbolic angle is an invariant measure with respect to the squeeze mapping, just as the circular angle is invariant under rotation.[25]

The Gudermannian function gives a direct relationship between the circular functions and the hyperbolic functions that does not involve complex numbers.

The graph of the function is the catenary, the curve formed by a uniform flexible chain, hanging freely between two fixed points under uniform gravity.

Relationship to the exponential function

[edit]The decomposition of the exponential function in its even and odd parts gives the identities and Combined with Euler's formula this gives for the general complex exponential function.

Additionally,

Hyperbolic functions for complex numbers

[edit] |

|

|

|

|

|

Since the exponential function can be defined for any complex argument, we can also extend the definitions of the hyperbolic functions to complex arguments. The functions sinh z and cosh z are then holomorphic.

Relationships to ordinary trigonometric functions are given by Euler's formula for complex numbers: so:

Thus, hyperbolic functions are periodic with respect to the imaginary component, with period ( for hyperbolic tangent and cotangent).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Weisstein, Eric W. "Hyperbolic Functions". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ (1999) Collins Concise Dictionary, 4th edition, HarperCollins, Glasgow, ISBN 0 00 472257 4, p. 1386

- ^ a b Collins Concise Dictionary, p. 328

- ^ a b "Hyperbolic Functions". www.mathsisfun.com. Retrieved 2020-08-29.

- ^ Collins Concise Dictionary, p. 1520

- ^ Collins Concise Dictionary, p. 329

- ^ tanh

- ^ Collins Concise Dictionary, p. 1340

- ^ Woodhouse, N. M. J. (2003), Special Relativity, London: Springer, p. 71, ISBN 978-1-85233-426-0

- ^ Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene A., eds. (1972), Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0

- ^ Some examples of using arcsinh found in Google Books.

- ^ Niven, Ivan (1985). Irrational Numbers. Vol. 11. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 9780883850381. JSTOR 10.4169/j.ctt5hh8zn.

- ^ a b George F. Becker; C. E. Van Orstrand (1909). Hyperbolic Functions. Universal Digital Library. The Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ a b c d e f McMahon, James (1896). Hyperbolic Functions. Osmania University, Digital Library Of India. John Wiley And Sons.

- ^ a b c d Bradley, Robert E.; D'Antonio, Lawrence A.; Sandifer, Charles Edward. Euler at 300: an appreciation. Mathematical Association of America, 2007. Page 100.

- ^ Becker, Georg F. Hyperbolic functions. Read Books, 1931. Page xlviii.

- ^ N.P., Bali (2005). Golden Integral Calculus. Firewall Media. p. 472. ISBN 81-7008-169-6.

- ^ Steeb, Willi-Hans (2005). Nonlinear Workbook, The: Chaos, Fractals, Cellular Automata, Neural Networks, Genetic Algorithms, Gene Expression Programming, Support Vector Machine, Wavelets, Hidden Markov Models, Fuzzy Logic With C++, Java And Symbolicc++ Programs (3rd ed.). World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 281. ISBN 978-981-310-648-2. Extract of page 281 (using lambda=1)

- ^ Oldham, Keith B.; Myland, Jan; Spanier, Jerome (2010). An Atlas of Functions: with Equator, the Atlas Function Calculator (2nd, illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-387-48807-3. Extract of page 290

- ^ Osborn, G. (July 1902). "Mnemonic for hyperbolic formulae". The Mathematical Gazette. 2 (34): 189. doi:10.2307/3602492. JSTOR 3602492. S2CID 125866575.

- ^ Martin, George E. (1986). The foundations of geometry and the non-Euclidean plane (1st corr. ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 416. ISBN 3-540-90694-0.

- ^ "Prove the identity tanh(x/2) = (cosh(x) - 1)/sinh(x)". StackExchange (mathematics). Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ Audibert, Jean-Yves (2009). "Fast learning rates in statistical inference through aggregation". The Annals of Statistics. p. 1627. [1]

- ^ Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W., eds. (2010), "Hyperbolic functions", NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, MR 2723248.

- ^ Haskell, Mellen W., "On the introduction of the notion of hyperbolic functions", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 1:6:155–9, full text

External links

[edit]- "Hyperbolic functions", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Hyperbolic functions on PlanetMath

- GonioLab: Visualization of the unit circle, trigonometric and hyperbolic functions (Java Web Start)

- Web-based calculator of hyperbolic functions

Hyperbolic functions

View on GrokipediaHistory and Notation

Historical Development

The study of hyperbolas dates back to ancient Greek geometry, where they were first recognized as one of the conic sections. Around 350 BC, Menaechmus discovered the hyperbola while attempting to solve the Delian problem of duplicating the cube, describing it as the intersection of a cone with a plane. Later, in the 3rd century BC, Apollonius of Perga provided a systematic treatment in his work Conics, naming the curve "hyperbola" (meaning "excess") and developing its properties, including parametric representations that related points on the curve to parameters, laying foundational geometric insights that would later inspire hyperbolic functions.[4] A key milestone in the evolution toward hyperbolic functions occurred in the late 17th century with the catenary problem, which describes the shape of a hanging chain under gravity. In 1690, Jakob Bernoulli posed this challenge in Acta Eruditorum, and his brother Johann Bernoulli solved it in 1691, deriving the curve's equation through differential methods, though without explicit hyperbolic terminology; the solution's form was later recognized as involving what became the hyperbolic cosine. This application highlighted the utility of such functions in solving differential equations related to physical curves.[5] The formal introduction of hyperbolic functions emerged in the 18th century. In 1757, Italian mathematician Vincenzo Riccati pioneered their definition in the first volume of Opusculorum ad res physicas et mathematicas pertinentium, expressing sinh and cosh via integrals and linking them to the geometry of the unit hyperbola, complete with addition formulas and derivatives; he denoted them as Sh and Ch. Building on this, Johann Heinrich Lambert provided the first systematic development in his 1761 memoir Mémoire sur les suites, published in 1768, where he defined them logarithmically as "sinus hyperbolicus" and "cosinus hyperbolicus," establishing their trigonometric analogies without complex numbers and popularizing their use in analysis. Leonhard Euler advanced their exponential expressions, such as relating cosh x to (e^x + e^{-x})/2, in works like his 1748 Introductio in analysin infinitorum, refining earlier integral forms into more accessible analytic tools.[6][7][5] In the 20th century, a significant milestone came in 1908, when Hermann Minkowski incorporated hyperbolic functions into special relativity, interpreting Lorentz transformations as hyperbolic rotations in spacetime, thus extending their role in physics.[5][8]Standard Notation

The standard notation for hyperbolic functions employs abbreviations that parallel those of trigonometric functions, with an added "h" to denote the hyperbolic variant. The primary functions are denoted as follows: hyperbolic sine by , hyperbolic cosine by , hyperbolic tangent by , hyperbolic cotangent by , hyperbolic secant by , and hyperbolic cosecant by .[9][10] These symbols, introduced in the 19th century, facilitate consistency with trigonometric notation, where corresponds to and to .[11] Historical alternatives include and for hyperbolic sine and cosine, respectively, as seen in early 20th-century mathematical tables. In physics and older literature, abbreviated forms such as and are common for hyperbolic sine and cosine.[12][13] For inverse hyperbolic functions, the notations , , , , , and are standard, with alternative arc notations like , , , and so on also widely used.[14][15] Typographical guidelines recommend rendering these in italicized lowercase letters within mathematical expressions, with the full terms "hyperbolic sine" or "hyperbolic cosine" used in prose for clarity. Pronunciation typically follows "shine" for , "cosh" for , and "thanch" for , though regional variations exist, such as "sinch" or "cynsh" for .[16]Definitions

Exponential Definitions

The hyperbolic sine and cosine functions are fundamentally defined in terms of the exponential function for real arguments . The hyperbolic sine is given by while the hyperbolic cosine is These definitions provide a direct means for computation and reveal the functions' close ties to exponential growth and decay.[17][18] The remaining hyperbolic functions are derived from and . The hyperbolic tangent is the ratio , the hyperbolic cotangent is , the hyperbolic secant is , and the hyperbolic cosecant is . These expressions maintain the real domain and inherit properties from their foundational components.[19][20] A key behavioral aspect stems from the exponential forms: is an even function, satisfying , whereas is odd, with . The derived functions follow suit, with , , and being odd, and even. As , and , while ; symmetrically, as , , , and . These limits highlight the non-periodic, monotonic nature of the functions for large .[17][21][22] The exponential definitions provide a real analog to the trigonometric functions, which are defined via the complex exponential in Euler's formula.Differential Equation Definitions

Hyperbolic functions can be characterized as solutions to specific linear ordinary differential equations (ODEs). In particular, both the hyperbolic cosine and hyperbolic sine functions serve as fundamental solutions to the second-order linear homogeneous ODE The general solution to this equation is given by where and are arbitrary constants determined by initial conditions.[23][21] This form arises because the characteristic equation has roots , leading to the linear combination of and , though the hyperbolic basis emphasizes the even and odd components.[24] The individual functions are uniquely specified by their initial conditions at : and , with derivatives satisfying and . These conditions ensure that and form a basis for the solution space, guaranteeing uniqueness for the initial value problem.[23][24] Additionally, the hyperbolic sine can be defined as the unique solution to the first-order nonlinear ODE subject to the initial condition . This follows from the identity , which implies . Similarly, the hyperbolic cosine satisfies for , with initial condition ; this defines for (where ), and the full even function is obtained by extension: . These first-order equations highlight the autonomous nature of the functions and their role in separable ODEs.[23][24] Such differential equation formulations connect hyperbolic functions to physical contexts, such as the catenary curve describing a uniformly loaded hanging chain, where the shape satisfies and resolves to .[23] These definitions via ODEs are equivalent to exponential representations but emphasize analytical solutions to boundary value problems.[23]Complex Trigonometric Definitions

Hyperbolic functions can be defined using trigonometric functions evaluated at purely imaginary arguments, providing an analogy between hyperbolic and circular trigonometry in the complex plane. Specifically, the hyperbolic sine and cosine are expressed as where is the imaginary unit and and are the standard trigonometric functions.[10] These definitions establish a direct connection to the exponential forms of the hyperbolic functions. Substituting Euler's formula, , into the trigonometric expressions yields the equivalence. For instance, , and similarly, .[10][9] The remaining hyperbolic functions follow analogously from their trigonometric counterparts: These relations highlight the structural similarities while adapting for the hyperbolic case.[9][25] Unlike the trigonometric functions, which are periodic with period on the real line, the hyperbolic functions are non-periodic for real arguments. However, in the complex domain, they exhibit periodicity with imaginary periods, such as for and , reflecting their trigonometric origins but shifted into the hyperbolic regime.[10]Fundamental Identities and Properties

Addition and Subtraction Formulas

The addition and subtraction formulas for hyperbolic functions are fundamental identities that express the hyperbolic sine and cosine of a sum or difference of arguments in terms of products of the individual functions, mirroring the angle-addition theorems in trigonometry but without the alternating signs characteristic of circular functions. These formulas arise naturally from the exponential definitions of the hyperbolic functions and are essential for simplifying expressions involving combined arguments.[26] The sum formulas are given by: These can be derived by substituting the exponential definitions of and into , expanding, and simplifying the resulting expressions. A similar derivation applies to , resulting in the positive product identity.[26] The difference formulas follow by replacing with in the sum formulas, leveraging the identities and : These can be verified analogously via exponential substitution for .[26] For the hyperbolic tangent, the addition formula is derived by dividing the sum formulas for and : Dividing numerator and denominator by simplifies this to which highlights the similarity to the trigonometric tangent addition formula.[26]Multiple-Angle and Half-Argument Formulas

Multiple-angle formulas for hyperbolic functions express sinh(nx) and cosh(nx) in terms of powers of sinh(x) and cosh(x), analogous to their trigonometric counterparts but derived from the addition formulas for hyperbolic functions.[27] The double-angle formulas are fundamental and given by These identities follow directly from applying the addition formula and with .[27][28] For the triple angle, the formulas are These can be obtained by composing the double-angle formulas or using the addition formula iteratively.[27] Half-argument formulas provide expressions for half-angles in terms of the full argument: The signs depend on the quadrant or branch considered, with the principal values often taken positive for real . These derive from solving the double-angle relations for half-arguments.[27]Square and Power Identities

One of the fundamental identities for hyperbolic functions is the hyperbolic Pythagorean theorem, which states that This identity is derived directly from the exponential definitions of the hyperbolic functions and serves as an analog to the trigonometric identity . Power-reduction formulas express the squares of hyperbolic sine and cosine in terms of the double-angle hyperbolic cosine: These formulas follow from rearranging the double-angle identity for combined with the Pythagorean identity. For higher powers, identities relate cubes and other powers to multiple-angle expressions. For example, the cube of the hyperbolic sine is given by which is obtained by solving the triple-angle formula for the cubic term, yielding . A similar relation holds for the hyperbolic cosine: derived from . These power identities are useful in expanding series representations and solving differential equations involving hyperbolic functions.[29]Characterizing Properties of Individual Functions

Hyperbolic Cosine and Sine

The hyperbolic cosine function, denoted , and the hyperbolic sine function, denoted , are defined in terms of exponentials as and . These functions form the foundational pair of hyperbolic functions, analogous to cosine and sine in trigonometric contexts but exhibiting unbounded growth rather than periodicity.[30] A key distinguishing property is their symmetry: is an even function, satisfying for all real , while is an odd function, satisfying . This evenness of reflects its symmetry about the y-axis in the real plane, whereas the oddness of implies antisymmetry about the origin.[17] For real arguments, , achieving its global minimum value of 1 at , and remains positive everywhere. In contrast, passes through the origin with and is strictly monotonic increasing over all real , ranging from to . These behaviors underscore as a convex "U-shaped" curve and as a strictly rising S-shaped curve.[31] As becomes large, both functions exhibit exponential growth: and , dominating any polynomial behavior and reflecting their ties to exponential functions. Geometrically, generates the shape of a catenary, the curve formed by a uniformly dense hanging chain under gravity, described by for scaling constant .[32] The arc length along this catenary from the vertex to a point at parameter is given by , highlighting 's role in measuring hyperbolic "distances."[33]Hyperbolic Tangent and Cotangent

The hyperbolic tangent function, defined as the ratio , and the hyperbolic cotangent function, , exhibit distinct behaviors arising from their definitions in terms of the fundamental hyperbolic sine and cosine. For real arguments , the hyperbolic tangent is strictly bounded such that , with the function being odd and strictly increasing across the entire real line.[34] As , approaches asymptotically, and a more precise approximation for large is .[35] The addition formula for the hyperbolic tangent is , which facilitates computations involving sums or differences of arguments. In contrast, the hyperbolic cotangent has simple poles at for integers , including a pole on the real axis at , rendering it undefined there and introducing discontinuities.[34] On the real line excluding the origin, is real-valued and monotonic: strictly decreasing on from to , and strictly decreasing on from to .[34] For large , , approaching as . The addition formula is .Hyperbolic Secant and Cosecant

The hyperbolic secant function, denoted , is defined as .[10] It attains a maximum value of 1 at and exhibits exponential decay to 0 as increases, approaching 0 asymptotically for large .[36] This bell-shaped profile makes particularly useful in modeling localized phenomena, such as optical solitons in nonlinear wave equations, where it describes stable, non-dispersive pulses. The Fourier transform of is , highlighting its self-similar transform properties under certain scalings.[37] The hyperbolic cosecant function, denoted , is defined as .[10] As an odd function, , it features a pole at where it diverges to .[36] For large positive , decays exponentially to 0, asymptotically ; for large negative , .[1] Both functions are integrable over appropriate intervals. The indefinite integral of is .[38] For , the indefinite integral over is .[39] These antiderivatives underscore the functions' roles in solving differential equations involving exponential decay.Inverse Hyperbolic Functions

Logarithmic Expressions

The inverse hyperbolic functions can be expressed explicitly in terms of natural logarithms, providing closed-form representations that facilitate computation and analysis in real analysis. These expressions arise from the exponential definitions of the hyperbolic functions by solving for the inverse. For instance, the inverse hyperbolic sine, denoted or , satisfies , where . Substituting and solving the resulting quadratic equation in yields the logarithmic form.[15] For real , the principal value is given by which holds for all real and corresponds to the branch where the result is real-valued. Similarly, for the inverse hyperbolic cosine, or , set with for the principal branch, leading to for . The inverse hyperbolic tangent, or , derives from , which simplifies to solving for in terms of the ratio of exponentials, giving for . For the inverse hyperbolic cotangent, or , the relation leads to for .[40] The remaining inverse functions follow analogous derivations. The inverse hyperbolic secant, or , uses , resulting in for .[41] Finally, for the inverse hyperbolic cosecant, or , from , for , ensuring the principal real branch.[42] These logarithmic forms underscore the connection between hyperbolic and exponential functions, enabling efficient evaluation in computational contexts.[15]Domains and Ranges

The inverse hyperbolic functions are defined on specific domains over the real and complex numbers, with principal branches selected to ensure analyticity in cut planes. For real arguments, these functions are single-valued and real-valued on their principal domains, reflecting their roles as inverses of the corresponding hyperbolic functions. The domains and ranges vary by function, determined by the monotonicity of the hyperbolic functions and the need to avoid singularities. Over the real numbers, the principal domain and range for each inverse hyperbolic function are as follows:| Function | Domain | Range |

|---|---|---|

| arcsinh z | (−∞, ∞) | (−∞, ∞) |

| arccosh z | [1, ∞) | [0, ∞) |

| arctanh z | (−1, 1) | (−∞, ∞) |

| arccoth z | (−∞, −1) ∪ (1, ∞) | (−∞, ∞) |

| arcsech z | (0, 1] | [0, ∞) |

| arccsch z | (−∞, 0) ∪ (0, ∞) | (−∞, ∞) |

Calculus Aspects

First Derivatives

The first derivatives of the hyperbolic functions are derived from their exponential definitions, yielding results analogous to those of the trigonometric functions but with distinct signs. Specifically, the derivative of the hyperbolic sine function is the hyperbolic cosine: This follows from the definition and the known derivatives of the exponential functions.[43] Similarly, the derivative of the hyperbolic cosine is the hyperbolic sine: obtained via .[43] For the hyperbolic tangent, defined as , the quotient rule yields where .[44] The derivatives of the remaining functions are: [45] The derivatives of the inverse hyperbolic functions are also fundamental in calculus. For the inverse hyperbolic sine, which holds for all real and is derived using implicit differentiation from , leading to and substituting the identity .[17] Likewise, for the inverse hyperbolic cosine (defined for ), obtained analogously via implicit differentiation and the hyperbolic identity.[46] When applying the chain rule to composite functions, the derivatives retain their form scaled by the inner function's derivative. For instance, the derivative of is , mirroring the structure for as . This pattern extends naturally to other hyperbolic functions, facilitating computations in more complex expressions.[45] Geometrically, these derivatives interpret the slopes of curves defined by hyperbolic functions, particularly in the catenary, the shape of a hanging chain under uniform gravity modeled by for some constant . The slope of this curve is , representing the tangent of the angle that the chain makes with the horizontal, which equals the ratio of arc length from the vertex to the horizontal tension component.[47] This connection underscores the physical relevance of the derivatives in describing equilibrium shapes.[32]Integrals and Antiderivatives

The indefinite integrals of the primary hyperbolic functions are straightforward and mirror their differentiation rules. These results follow from the exponential definitions of the functions or direct verification via differentiation.[48] For the remaining hyperbolic functions, the antiderivatives involve logarithmic or inverse trigonometric expressions: The integral of arises from substitution using the identity , while the form can be derived via the substitution , leveraging . Equivalent representations for include . The integrals for and follow similarly from their definitions and identities.[48][49] Reduction formulas facilitate evaluation of integrals involving powers of hyperbolic functions by recursively lowering the exponent. For even or odd powers greater than 1, integration by parts with the identity (or its variants) yields: These formulas reduce the power by 2 each step until reaching a base case solvable by basic integrals. For odd powers, direct substitution (saving one factor for the differential) often simplifies computation without full recursion.[50] A notable definite integral involving the hyperbolic secant is the improper integral over the real line: This result can be established using contour integration in the complex plane, where the poles of lie on the imaginary axis, and the residue theorem applied to a suitable rectangular contour yields the value .[37]Second Derivatives and Higher

The second derivatives of the primary hyperbolic functions follow directly from their first derivatives. For the hyperbolic sine, since the first derivative is and the derivative of is .[51] Similarly, for the hyperbolic cosine, as its first derivative is and the second is then .[51] These relations highlight that both functions are eigenfunctions of the second derivative operator, satisfying up to the sign convention inherent in their definitions.[51] Higher-order derivatives exhibit a periodic pattern with period 4, arising from the repeated application of the differentiation rules or the characteristic differential equation . For , the th derivative is when is even and when is odd. For , it is for even and for odd . This recurrence can be expressed in the complex plane as (up to a phase factor), linking hyperbolic functions to rotations in the complex argument analogous to trigonometric derivatives.[51] For inverse hyperbolic functions, higher derivatives are more involved but follow from differentiating the known first derivatives. Consider , whose first derivative is .[52] The second derivative is then Similar expressions hold for other inverses, often involving rational functions of the form where is a polynomial.[52] These derivative properties are essential in solving linear ordinary differential equations (ODEs). The equation has the general solution , where and are constants determined by initial conditions.[51] Higher-order linear ODEs with constant coefficients can likewise leverage the recurrence patterns, reducing solutions to linear combinations of hyperbolic functions or their shifts. For instance, the fourth-order equation factors into , yielding solutions involving , , , and .[51]Series and Other Representations

Taylor Series Expansions

The Taylor series expansions of the hyperbolic sine and cosine functions centered at are infinite power series that converge for all real and complex values of . The series for is derived from repeated differentiation of its definition . Similarly, the series for is obtained analogously from . These expansions mirror the Taylor series for and but lack alternating signs, reflecting the absence of oscillatory behavior in hyperbolic functions.[53] The hyperbolic tangent function, defined as , has a Taylor series expansion around given by where denotes the -th Bernoulli number (with , , etc.). This series arises from the quotient of the and expansions and converges within the radius , limited by the poles of at for integer . The involvement of Bernoulli numbers highlights a connection to broader combinatorial and analytic structures, as these numbers frequently parameterize series for rational functions of exponentials.[54][53] For large positive arguments, asymptotic expansions of hyperbolic functions can be obtained directly from their exponential representations, providing efficient approximations beyond the regime of power series. As , These leading-order terms capture the dominant exponential growth or saturation, with higher-order corrections available by including additional powers of (for ) or (for and ). For , the approximations adjust by replacing with for and for , while . Such expansions are particularly useful for numerical computations and analytical estimates in regimes where full power series become inefficient.Infinite Products and Continued Fractions

The infinite product representations of hyperbolic functions provide a multiplicative factorization that reveals their zeros in the complex plane. For the hyperbolic sine function, it is given by which holds for all complex and encodes the simple zeros of at for each integer . This form was derived by Leonhard Euler in the 18th century as part of his work on infinite products for entire functions, drawing an analogy to the product expansion for the sine function and facilitating the study of function zeros through Weierstrass factorization principles. Similarly, the hyperbolic cosine admits the product reflecting its zeros at for positive integers . These representations converge uniformly on compact subsets of the complex plane avoiding the poles, and they parallel the Wallis product for in their historical development, where Euler used similar techniques to connect products to integrals and special values.[55][56] Continued fractions offer another non-power series expansion, particularly useful for computational approximations and asymptotic analysis. The hyperbolic tangent function has the continued fraction representation known as Lambert's continued fraction, which converges for all complex in the right half-plane and can be extended analytically. This form, originally developed by Johann Heinrich Lambert in 1761 for the tangent function and adapted to its hyperbolic counterpart, arises from integral representations or differential equations satisfied by , and its partial quotients grow linearly, ensuring rapid convergence compared to series expansions for moderate . The structure highlights the poles of at , analogous to the infinite products, and has been applied in numerical methods for evaluating hyperbolic functions near their singularities.[54]Extensions and Comparisons

Hyperbolic Functions of Complex Numbers

Hyperbolic functions extend naturally to complex arguments via their exponential definitions, preserving analyticity across the entire complex plane. The hyperbolic sine is defined as and the hyperbolic cosine as for any complex number . These functions are entire, meaning they are holomorphic everywhere in the complex plane with no singularities. The remaining hyperbolic functions—tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant—are then expressed as ratios: , , , and . These ratio functions inherit poles from the zeros of their denominators.[9] The functions and exhibit periodicity in the complex plane with period , satisfying and . This follows directly from the periodicity of the exponential function, . In contrast, has fundamental period . The zeros of occur at for integers , leading to simple poles of at these points. Similarly, has zeros at .[10] For a complex argument with real and , the hyperbolic sine decomposes into real and imaginary parts as The hyperbolic cosine follows analogously: These identities arise from substituting the complex form into the exponential definitions and applying Euler's formula. They highlight the interplay between hyperbolic and trigonometric functions in the complex domain.[9] The inverse hyperbolic functions, such as , , and , are multivalued in the complex plane and require branch cuts to define single-valued principal branches. For , the principal branch employs cuts along the imaginary axis from to and from to . The function uses cuts from to and from 1 to along the real axis. For , cuts run from to and from to on the imaginary axis. These branch structures ensure analytic continuation while respecting the multivalued nature stemming from the logarithmic expressions underlying the inverses.[15]Relation to Exponential and Trigonometric Functions

Hyperbolic functions are fundamentally defined in terms of exponential functions. The hyperbolic cosine is given by , and the hyperbolic sine by .[17] These definitions extend to the other hyperbolic functions, such as , which can all be expressed as combinations of and .[19] From these exponential forms, key identities emerge that link hyperbolic functions directly to the exponential function. For instance, and .[24] The fundamental identity follows directly from substituting the exponential definitions and simplifying.[25] Hyperbolic functions also exhibit a close analogy to trigonometric functions through complex arguments. Specifically, and , where is the imaginary unit, revealing that hyperbolic functions can be viewed as trigonometric functions evaluated at imaginary arguments.[26] This connection underscores the structural similarities between the two sets of functions, though they differ in their geometric interpretations: trigonometric functions parameterize the unit circle in Euclidean geometry (), while hyperbolic functions parameterize the unit hyperbola in hyperbolic geometry ().[18] The table below compares selected fundamental identities, highlighting the sign difference that reflects their distinct geometric roles:| Trigonometric Identity | Hyperbolic Identity |

|---|---|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\cosh x\,\cosh y&={\tfrac {1}{2}}{\bigl (}\!\!~\cosh(x+y)+\cosh(x-y){\bigr )}\\[5mu]\sinh x\,\sinh y&={\tfrac {1}{2}}{\bigl (}\!\!~\cosh(x+y)-\cosh(x-y){\bigr )}\\[5mu]\sinh x\,\cosh y&={\tfrac {1}{2}}{\bigl (}\!\!~\sinh(x+y)+\sinh(x-y){\bigr )}\\[5mu]\cosh x\,\sinh y&={\tfrac {1}{2}}{\bigl (}\!\!~\sinh(x+y)-\sinh(x-y){\bigr )}\\[5mu]\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ebcc6e905df736163061cf56b304ab50d7853739)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sinh \left({\frac {x}{2}}\right)&={\frac {\sinh x}{\sqrt {2(\cosh x+1)}}}&&=\operatorname {sgn} x\,{\sqrt {\frac {\cosh x-1}{2}}}\\[6px]\cosh \left({\frac {x}{2}}\right)&={\sqrt {\frac {\cosh x+1}{2}}}\\[6px]\tanh \left({\frac {x}{2}}\right)&={\frac {\sinh x}{\cosh x+1}}&&=\operatorname {sgn} x\,{\sqrt {\frac {\cosh x-1}{\cosh x+1}}}={\frac {e^{x}-1}{e^{x}+1}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/412a4ffd109486f684e515634b33447b13444954)