Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Inertial frame of reference

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

In classical physics and special relativity, an inertial frame of reference (also called an inertial space or a Galilean reference frame) is a frame of reference in which objects exhibit inertia: they remain at rest or in uniform motion relative to the frame until acted upon by external forces. In such a frame, the laws of nature can be observed without the need to correct for acceleration.

All frames of reference with zero acceleration are in a state of constant rectilinear motion (straight-line motion) with respect to one another. In such a frame, an object with zero net force acting on it, is perceived to move with a constant velocity, or, equivalently, Newton's first law of motion holds. Such frames are known as inertial. Some physicists, like Isaac Newton, originally thought that one of these frames was absolute — the one approximated by the fixed stars. However, this is not required for the definition, and it is now known that those stars are in fact moving, relative to one another.

According to the principle of special relativity, all physical laws look the same in all inertial reference frames, and no inertial frame is privileged over another. Measurements of objects in one inertial frame can be converted to measurements in another by a simple transformation — the Galilean transformation in Newtonian physics or the Lorentz transformation (combined with a translation) in special relativity; these approximately match when the relative speed of the frames is low, but differ as it approaches the speed of light.

By contrast, a non-inertial reference frame is accelerating. In such a frame, the interactions between physical objects vary depending on the acceleration of that frame with respect to an inertial frame. Viewed from the perspective of classical mechanics and special relativity, the usual physical forces caused by the interaction of objects have to be supplemented by fictitious forces caused by inertia.[1][2] Viewed from the perspective of general relativity theory, the fictitious (i.e. inertial) forces are attributed to geodesic motion in spacetime.

Due to Earth's rotation, its surface is not an inertial frame of reference. The Coriolis effect can deflect certain forms of motion as seen from Earth, and the centrifugal force will reduce the effective gravity at the equator. Nevertheless, for many applications the Earth is an adequate approximation of an inertial reference frame.

Introduction

[edit]The motion of a body can only be described relative to something else—other bodies, observers, or a set of spacetime coordinates. These are called frames of reference. According to the first postulate of special relativity, all physical laws take their simplest form in an inertial frame, and there exist multiple inertial frames interrelated by uniform translation:[3]

Special principle of relativity: If a system of coordinates K is chosen so that, in relation to it, physical laws hold good in their simplest form, the same laws hold good in relation to any other system of coordinates K' moving in uniform translation relatively to K.

— Albert Einstein: The foundation of the general theory of relativity, Section A, §1

This simplicity manifests itself in that inertial frames have self-contained physics without the need for external causes, while physics in non-inertial frames has external causes.[4] The principle of simplicity can be used within Newtonian physics as well as in special relativity:[5][6]

The laws of Newtonian mechanics do not always hold in their simplest form...If, for instance, an observer is placed on a disc rotating relative to the earth, he/she will sense a 'force' pushing him/her toward the periphery of the disc, which is not caused by any interaction with other bodies. Here, the acceleration is not the consequence of the usual force, but of the so-called inertial force. Newton's laws hold in their simplest form only in a family of reference frames, called inertial frames. This fact represents the essence of the Galilean principle of relativity:

The laws of mechanics have the same form in all inertial frames.

— Milutin Blagojević: Gravitation and Gauge Symmetries, p. 4

However, this definition of inertial frames is understood to apply in the Newtonian realm and ignores relativistic effects.

In practical terms, the equivalence of inertial reference frames means that scientists within a box moving with a constant absolute velocity cannot determine this velocity by any experiment. Otherwise, the differences would set up an absolute standard reference frame.[7][8] According to this definition, supplemented with the constancy of the speed of light, inertial frames of reference transform among themselves according to the Poincaré group of symmetry transformations, of which the Lorentz transformations are a subgroup.[9] In Newtonian mechanics, inertial frames of reference are related by the Galilean group of symmetries.

Newton's inertial frame of reference

[edit]Absolute space

[edit]Newton posited an absolute space considered well-approximated by a frame of reference stationary relative to the fixed stars. An inertial frame was then one in uniform translation relative to absolute space. However, some "relativists",[10] even at the time of Newton, felt that absolute space was a defect of the formulation, and should be replaced.

The expression inertial frame of reference (German: Inertialsystem) was coined by Ludwig Lange in 1885, to replace Newton's definitions of "absolute space and time" with a more operational definition:[11][12]

A reference frame in which a mass point thrown from the same point in three different (non co-planar) directions follows rectilinear paths each time it is thrown, is called an inertial frame.[13]

The inadequacy of the notion of "absolute space" in Newtonian mechanics is spelled out by Blagojevich:[14]

- The existence of absolute space contradicts the internal logic of classical mechanics since, according to the Galilean principle of relativity, none of the inertial frames can be singled out.

- Absolute space does not explain inertial forces since they are related to acceleration with respect to any one of the inertial frames.

- Absolute space acts on physical objects by inducing their resistance to acceleration but it cannot be acted upon.

— Milutin Blagojević: Gravitation and Gauge Symmetries, p. 5

The utility of operational definitions was carried much further in the special theory of relativity.[15] Some historical background including Lange's definition is provided by DiSalle, who says in summary:[16]

The original question, "relative to what frame of reference do the laws of motion hold?" is revealed to be wrongly posed. The laws of motion essentially determine a class of reference frames, and (in principle) a procedure for constructing them.

Newtonian mechanics

[edit]Classical theories that use the Galilean transformation postulate the equivalence of all inertial reference frames. The Galilean transformation transforms coordinates from one inertial reference frame, , to another, , by simple addition or subtraction of coordinates:

where r0 and t0 represent shifts in the origin of space and time, and v is the relative velocity of the two inertial reference frames. Under Galilean transformations, the time t2 − t1 between two events is the same for all reference frames and the distance between two simultaneous events (or, equivalently, the length of any object, |r2 − r1|) is also the same.

Within the realm of Newtonian mechanics, an inertial frame of reference, or inertial reference frame, is one in which Newton's first law of motion is valid.[17] However, the principle of special relativity generalizes the notion of an inertial frame to include all physical laws, not simply Newton's first law.

Newton viewed the first law as valid in any reference frame that is in uniform motion (neither rotating nor accelerating) relative to absolute space; as a practical matter, "absolute space" was considered to be the fixed stars[18][19] In the theory of relativity the notion of absolute space or a privileged frame is abandoned, and an inertial frame in the field of classical mechanics is defined as:[20][21]

An inertial frame of reference is one in which the motion of a particle not subject to forces is in a straight line at constant speed.

Hence, with respect to an inertial frame, an object or body accelerates only when a physical force is applied, and (following Newton's first law of motion), in the absence of a net force, a body at rest will remain at rest and a body in motion will continue to move uniformly—that is, in a straight line and at constant speed. Newtonian inertial frames transform among each other according to the Galilean group of symmetries.

If this rule is interpreted as saying that straight-line motion is an indication of zero net force, the rule does not identify inertial reference frames because straight-line motion can be observed in a variety of frames. If the rule is interpreted as defining an inertial frame, then being able to determine when zero net force is applied is crucial. The problem was summarized by Einstein:[22]

The weakness of the principle of inertia lies in this, that it involves an argument in a circle: a mass moves without acceleration if it is sufficiently far from other bodies; we know that it is sufficiently far from other bodies only by the fact that it moves without acceleration.

— Albert Einstein: The Meaning of Relativity, p. 58

There are several approaches to this issue. One approach is to argue that all real forces drop off with distance from their sources in a known manner, so it is only needed that a body is far enough away from all sources to ensure that no force is present.[23] A possible issue with this approach is the historically long-lived view that the distant universe might affect matters (Mach's principle). Another approach is to identify all real sources for real forces and account for them. A possible issue with this approach is the possibility of missing something, or accounting inappropriately for their influence, perhaps, again, due to Mach's principle and an incomplete understanding of the universe. A third approach is to look at the way the forces transform when shifting reference frames. Fictitious forces, those that arise due to the acceleration of a frame, disappear in inertial frames and have complicated rules of transformation in general cases. Based on the universality of physical law and the request for frames where the laws are most simply expressed, inertial frames are distinguished by the absence of such fictitious forces.

Newton enunciated a principle of relativity himself in one of his corollaries to the laws of motion:[24][25]

The motions of bodies included in a given space are the same among themselves, whether that space is at rest or moves uniformly forward in a straight line.

— Isaac Newton: Principia, Corollary V, p. 88 in Andrew Motte translation

This principle differs from the special principle in two ways: first, it is restricted to mechanics, and second, it makes no mention of simplicity. It shares the special principle of the invariance of the form of the description among mutually translating reference frames.[26] The role of fictitious forces in classifying reference frames is pursued further below.

Special relativity

[edit]Einstein's theory of special relativity, like Newtonian mechanics, postulates the equivalence of all inertial reference frames. However, because special relativity postulates that the speed of light in free space is invariant, the transformation between inertial frames is the Lorentz transformation, not the Galilean transformation which is used in Newtonian mechanics.

The invariance of the speed of light leads to counter-intuitive phenomena, such as time dilation, length contraction, and the relativity of simultaneity. The predictions of special relativity have been extensively verified experimentally.[27] The Lorentz transformation reduces to the Galilean transformation as the speed of light approaches infinity or as the relative velocity between frames approaches zero.[28]

Examples

[edit]Simple example

[edit]

Consider a situation common in everyday life. Two cars travel along a road, both moving at constant velocities. See Figure 1. At some particular moment, they are separated by 200 meters. The car in front is traveling at 22 meters per second and the car behind is traveling at 30 meters per second. If we want to find out how long it will take the second car to catch up with the first, there are three obvious "frames of reference" that we could choose.[29]

First, we could observe the two cars from the side of the road. We define our "frame of reference" S as follows. We stand on the side of the road and start a stop-clock at the exact moment that the second car passes us, which happens to be when they are a distance d = 200 m apart. Since neither of the cars is accelerating, we can determine their positions by the following formulas, where is the position in meters of car one after time t in seconds and is the position of car two after time t.

Notice that these formulas predict at t = 0 s the first car is 200m down the road and the second car is right beside us, as expected. We want to find the time at which . Therefore, we set and solve for , that is:

Alternatively, we could choose a frame of reference S′ situated in the first car. In this case, the first car is stationary and the second car is approaching from behind at a speed of v2 − v1 = 8 m/s. To catch up to the first car, it will take a time of d/v2 − v1 = 200/8 s, that is, 25 seconds, as before. Note how much easier the problem becomes by choosing a suitable frame of reference. The third possible frame of reference would be attached to the second car. That example resembles the case just discussed, except the second car is stationary and the first car moves backward towards it at 8 m/s.

It would have been possible to choose a rotating, accelerating frame of reference, moving in a complicated manner, but this would have served to complicate the problem unnecessarily. One can convert measurements made in one coordinate system to another. For example, suppose that your watch is running five minutes fast compared to the local standard time. If you know that this is the case, when somebody asks you what time it is, you can deduct five minutes from the time displayed on your watch to obtain the correct time. The measurements that an observer makes about a system depend therefore on the observer's frame of reference (you might say that the bus arrived at 5 past three, when in fact it arrived at three).

Additional example

[edit]

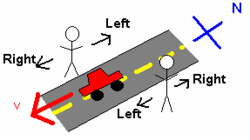

For a simple example involving only the orientation of two observers, consider two people standing, facing each other on either side of a north-south street. See Figure 2. A car drives past them heading south. For the person facing east, the car was moving to the right. However, for the person facing west, the car was moving to the left. This discrepancy is because the two people used two different frames of reference from which to investigate this system.

For a more complex example involving observers in relative motion, consider Alfred, who is standing on the side of a road watching a car drive past him from left to right. In his frame of reference, Alfred defines the spot where he is standing as the origin, the road as the x-axis, and the direction in front of him as the positive y-axis. To him, the car moves along the x axis with some velocity v in the positive x-direction. Alfred's frame of reference is considered an inertial frame because he is not accelerating, ignoring effects such as Earth's rotation and gravity.

Now consider Betsy, the person driving the car. Betsy, in choosing her frame of reference, defines her location as the origin, the direction to her right as the positive x-axis, and the direction in front of her as the positive y-axis. In this frame of reference, it is Betsy who is stationary and the world around her that is moving – for instance, as she drives past Alfred, she observes him moving with velocity v in the negative y-direction. If she is driving north, then north is the positive y-direction; if she turns east, east becomes the positive y-direction.

Finally, as an example of non-inertial observers, assume Candace is accelerating her car. As she passes by him, Alfred measures her acceleration and finds it to be a in the negative x-direction. Assuming Candace's acceleration is constant, what acceleration does Betsy measure? If Betsy's velocity v is constant, she is in an inertial frame of reference, and she will find the acceleration to be the same as Alfred in her frame of reference, a in the negative y-direction. However, if she is accelerating at rate A in the negative y-direction (in other words, slowing down), she will find Candace's acceleration to be a′ = a − A in the negative y-direction—a smaller value than Alfred has measured. Similarly, if she is accelerating at rate A in the positive y-direction (speeding up), she will observe Candace's acceleration as a′ = a + A in the negative y-direction—a larger value than Alfred's measurement.

Non-inertial frames

[edit]Here the relation between inertial and non-inertial observational frames of reference is considered. The basic difference between these frames is the need in non-inertial frames for fictitious forces, as described below.

General relativity

[edit]General relativity is based upon the principle of equivalence:[30][31]

There is no experiment observers can perform to distinguish whether an acceleration arises because of a gravitational force or because their reference frame is accelerating.

— Douglas C. Giancoli, Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics, p. 155.

This idea was introduced in Einstein's 1907 article "Principle of Relativity and Gravitation" and later developed in 1911.[32] Support for this principle is found in the Eötvös experiment, which determines whether the ratio of inertial to gravitational mass is the same for all bodies, regardless of size or composition. To date no difference has been found to a few parts in 1011.[33] For some discussion of the subtleties of the Eötvös experiment, such as the local mass distribution around the experimental site (including a quip about the mass of Eötvös himself), see Franklin.[34]

Einstein's general theory modifies the distinction between nominally "inertial" and "non-inertial" effects by replacing special relativity's "flat" Minkowski Space with a metric that produces non-zero curvature. In general relativity, the principle of inertia is replaced with the principle of geodesic motion, whereby objects move in a way dictated by the curvature of spacetime. As a consequence of this curvature, it is not a given in general relativity that inertial objects moving at a particular rate with respect to each other will continue to do so. This phenomenon of geodesic deviation means that inertial frames of reference do not exist globally as they do in Newtonian mechanics and special relativity.

However, the general theory reduces to the special theory over sufficiently small regions of spacetime, where curvature effects become less important and the earlier inertial frame arguments can come back into play.[35][36] Consequently, modern special relativity is now sometimes described as only a "local theory".[37] "Local" can encompass, for example, the entire Milky Way galaxy: The astronomer Karl Schwarzschild observed the motion of pairs of stars orbiting each other. He found that the two orbits of the stars of such a system lie in a plane, and the perihelion of the orbits of the two stars remains pointing in the same direction with respect to the Solar System. Schwarzschild pointed out that that was invariably seen: the direction of the angular momentum of all observed double star systems remains fixed with respect to the direction of the angular momentum of the Solar System. These observations allowed him to conclude that inertial frames inside the galaxy do not rotate with respect to one another, and that the space of the Milky Way is approximately Galilean or Minkowskian.[38]

Inertial frames and rotation

[edit]In an inertial frame, Newton's first law, the law of inertia, is satisfied: Any free motion has a constant magnitude and direction.[39] Newton's second law for a particle takes the form:

with F the net force (a vector), m the mass of a particle and a the acceleration of the particle (also a vector) which would be measured by an observer at rest in the frame. The force F is the vector sum of all "real" forces on the particle, such as contact forces, electromagnetic, gravitational, and nuclear forces.

In contrast, Newton's second law in a rotating frame of reference (a non-inertial frame of reference), rotating at angular rate Ω about an axis, takes the form:

which looks the same as in an inertial frame, but now the force F′ is the resultant of not only F, but also additional terms (the paragraph following this equation presents the main points without detailed mathematics):

where the angular rotation of the frame is expressed by the vector Ω pointing in the direction of the axis of rotation, and with magnitude equal to the angular rate of rotation Ω, symbol × denotes the vector cross product, vector xB locates the body and vector vB is the velocity of the body according to a rotating observer (different from the velocity seen by the inertial observer).

The extra terms in the force F′ are the "fictitious" forces for this frame, whose causes are external to the system in the frame. The first extra term is the Coriolis force, the second the centrifugal force, and the third the Euler force. These terms all have these properties: they vanish when Ω = 0; that is, they are zero for an inertial frame (which, of course, does not rotate); they take on a different magnitude and direction in every rotating frame, depending upon its particular value of Ω; they are ubiquitous in the rotating frame (affect every particle, regardless of circumstance); and they have no apparent source in identifiable physical sources, in particular, matter. Also, fictitious forces do not drop off with distance (unlike, for example, nuclear forces or electrical forces). For example, the centrifugal force that appears to emanate from the axis of rotation in a rotating frame increases with distance from the axis.

All observers agree on the real forces, F; only non-inertial observers need fictitious forces. The laws of physics in the inertial frame are simpler because unnecessary forces are not present.

In Newton's time the fixed stars were invoked as a reference frame, supposedly at rest relative to absolute space. In reference frames that were either at rest with respect to the fixed stars or in uniform translation relative to these stars, Newton's laws of motion were supposed to hold. In contrast, in frames accelerating with respect to the fixed stars, an important case being frames rotating relative to the fixed stars, the laws of motion did not hold in their simplest form, but had to be supplemented by the addition of fictitious forces, for example, the Coriolis force and the centrifugal force. Two experiments were devised by Newton to demonstrate how these forces could be discovered, thereby revealing to an observer that they were not in an inertial frame: the example of the tension in the cord linking two spheres rotating about their center of gravity, and the example of the curvature of the surface of water in a rotating bucket. In both cases, application of Newton's second law would not work for the rotating observer without invoking centrifugal and Coriolis forces to account for their observations (tension in the case of the spheres; parabolic water surface in the case of the rotating bucket).

As now known, the fixed stars are not fixed. Those that reside in the Milky Way turn with the galaxy, exhibiting proper motions. Those that are outside our galaxy (such as nebulae once mistaken to be stars) participate in their own motion as well, partly due to expansion of the universe, and partly due to peculiar velocities.[40] For instance, the Andromeda Galaxy is on collision course with the Milky Way at a speed of 117 km/s.[41] The concept of inertial frames of reference is no longer tied to either the fixed stars or to absolute space. Rather, the identification of an inertial frame is based on the simplicity of the laws of physics in the frame. The laws of nature take a simpler form in inertial frames of reference because in these frames one did not have to introduce inertial forces when writing down Newton's law of motion.[42]

In practice, using a frame of reference based upon the fixed stars as though it were an inertial frame of reference introduces little discrepancy. For example, the centrifugal acceleration of the Earth because of its rotation about the Sun is about thirty million times greater than that of the Sun about the galactic center.[43]

To illustrate further, consider the question: "Does the Universe rotate?" An answer might explain the shape of the Milky Way galaxy using the laws of physics,[44] although other observations might be more definitive; that is, provide larger discrepancies or less measurement uncertainty, like the anisotropy of the microwave background radiation or Big Bang nucleosynthesis.[45][46] The flatness of the Milky Way depends on its rate of rotation in an inertial frame of reference. If its apparent rate of rotation is attributed entirely to rotation in an inertial frame, a different "flatness" is predicted than if it is supposed that part of this rotation is actually due to rotation of the universe and should not be included in the rotation of the galaxy itself. Based upon the laws of physics, a model is set up in which one parameter is the rate of rotation of the Universe. If the laws of physics agree more accurately with observations in a model with rotation than without it, we are inclined to select the best-fit value for rotation, subject to all other pertinent experimental observations. If no value of the rotation parameter is successful and theory is not within observational error, a modification of physical law is considered, for example, dark matter is invoked to explain the galactic rotation curve. So far, observations show any rotation of the universe is very slow, no faster than once every 6×1013 years (10−13 rad/yr),[47] and debate persists over whether there is any rotation. However, if rotation were found, interpretation of observations in a frame tied to the universe would have to be corrected for the fictitious forces inherent in such rotation in classical physics and special relativity, or interpreted as the curvature of spacetime and the motion of matter along the geodesics in general relativity.[48]

When quantum effects are important, there are additional conceptual complications that arise in quantum reference frames.

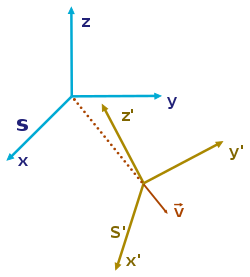

Primed frames

[edit]An accelerated frame of reference is often delineated as being the "primed" frame, and all variables that are dependent on that frame are notated with primes, e.g. x′, y′, a′.

The vector from the origin of an inertial reference frame to the origin of an accelerated reference frame is commonly notated as R. Given a point of interest that exists in both frames, the vector from the inertial origin to the point is called r, and the vector from the accelerated origin to the point is called r′.

From the geometry of the situation

Taking the first and second derivatives of this with respect to time

where V and A are the velocity and acceleration of the accelerated system with respect to the inertial system and v and a are the velocity and acceleration of the point of interest with respect to the inertial frame.

These equations allow transformations between the two coordinate systems; for example, Newton's second law can be written as

When there is accelerated motion due to a force being exerted there is manifestation of inertia. If an electric car designed to recharge its battery system when decelerating is switched to braking, the batteries are recharged, illustrating the physical strength of manifestation of inertia. However, the manifestation of inertia does not prevent acceleration (or deceleration), for manifestation of inertia occurs in response to change in velocity due to a force. Seen from the perspective of a rotating frame of reference the manifestation of inertia appears to exert a force (either in centrifugal direction, or in a direction orthogonal to an object's motion, the Coriolis effect).

A common sort of accelerated reference frame is a frame that is both rotating and translating (an example is a frame of reference attached to a CD which is playing while the player is carried).

This arrangement leads to the equation (see Fictitious force for a derivation):

or, to solve for the acceleration in the accelerated frame,

Multiplying through by the mass m gives

where

- (Euler force),

- (Coriolis force),

- (centrifugal force).

Separating non-inertial from inertial reference frames

[edit]Theory

[edit]

Inertial and non-inertial reference frames can be distinguished by the absence or presence of fictitious forces.[1][2]

The effect of this being in the noninertial frame is to require the observer to introduce a fictitious force into his calculations…

— Sidney Borowitz and Lawrence A Bornstein in A Contemporary View of Elementary Physics, p. 138

The presence of fictitious forces indicates the physical laws are not the simplest laws available, in terms of the special principle of relativity, a frame where fictitious forces are present is not an inertial frame:[49]

The equations of motion in a non-inertial system differ from the equations in an inertial system by additional terms called inertial forces. This allows us to detect experimentally the non-inertial nature of a system.

— V. I. Arnol'd: Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics Second Edition, p. 129

Bodies in non-inertial reference frames are subject to so-called fictitious forces (pseudo-forces); that is, forces that result from the acceleration of the reference frame itself and not from any physical force acting on the body. Examples of fictitious forces are the centrifugal force and the Coriolis force in rotating reference frames.

To apply the Newtonian definition of an inertial frame, the understanding of separation between "fictitious" forces and "real" forces must be made clear.

For example, consider a stationary object in an inertial frame. Being at rest, no net force is applied. But in a frame rotating about a fixed axis, the object appears to move in a circle, and is subject to centripetal force. How can it be decided that the rotating frame is a non-inertial frame? There are two approaches to this resolution: one approach is to look for the origin of the fictitious forces (the Coriolis force and the centrifugal force). It will be found there are no sources for these forces, no associated force carriers, no originating bodies.[50] A second approach is to look at a variety of frames of reference. For any inertial frame, the Coriolis force and the centrifugal force disappear, so application of the principle of special relativity would identify these frames where the forces disappear as sharing the same and the simplest physical laws, and hence rule that the rotating frame is not an inertial frame.

Newton examined this problem himself using rotating spheres, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. He pointed out that if the spheres are not rotating, the tension in the tying string is measured as zero in every frame of reference.[51] If the spheres only appear to rotate (that is, we are watching stationary spheres from a rotating frame), the zero tension in the string is accounted for by observing that the centripetal force is supplied by the centrifugal and Coriolis forces in combination, so no tension is needed. If the spheres really are rotating, the tension observed is exactly the centripetal force required by the circular motion. Thus, measurement of the tension in the string identifies the inertial frame: it is the one where the tension in the string provides exactly the centripetal force demanded by the motion as it is observed in that frame, and not a different value. That is, the inertial frame is the one where the fictitious forces vanish.

For linear acceleration, Newton expressed the idea of undetectability of straight-line accelerations held in common:[25]

If bodies, any how moved among themselves, are urged in the direction of parallel lines by equal accelerative forces, they will continue to move among themselves, after the same manner as if they had been urged by no such forces.

— Isaac Newton: Principia Corollary VI, p. 89, in Andrew Motte translation

This principle generalizes the notion of an inertial frame. For example, an observer confined in a free-falling lift will assert that he himself is a valid inertial frame, even if he is accelerating under gravity, so long as he has no knowledge about anything outside the lift. So, strictly speaking, inertial frame is a relative concept. With this in mind, inertial frames can collectively be defined as a set of frames which are stationary or moving at constant velocity with respect to each other, so that a single inertial frame is defined as an element of this set.

For these ideas to apply, everything observed in the frame has to be subject to a base-line, common acceleration shared by the frame itself. That situation would apply, for example, to the elevator example, where all objects are subject to the same gravitational acceleration, and the elevator itself accelerates at the same rate.

Applications

[edit]Inertial navigation systems used a cluster of gyroscopes and accelerometers to determine accelerations relative to inertial space. After a gyroscope is spun up in a particular orientation in inertial space, the law of conservation of angular momentum requires that it retain that orientation as long as no external forces are applied to it.[52]: 59 Three orthogonal gyroscopes establish an inertial reference frame, and the accelerators measure acceleration relative to that frame. The accelerations, along with a clock, can then be used to calculate the change in position. Thus, inertial navigation is a form of dead reckoning that requires no external input, and therefore cannot be jammed by any external or internal signal source.[53]

A gyrocompass, employed for navigation of seagoing vessels, finds the geometric north. It does so, not by sensing the Earth's magnetic field, but by using inertial space as its reference.[54] The outer casing of the gyrocompass device is held in such a way that it remains aligned with the local plumb line. When the gyroscope wheel inside the gyrocompass device is spun up, the way the gyroscope wheel is suspended causes the gyroscope wheel to gradually align its spinning axis with the Earth's axis. Alignment with the Earth's axis is the only direction for which the gyroscope's spinning axis can be stationary with respect to the Earth and not be required to change direction with respect to inertial space. After being spun up, a gyrocompass can reach the direction of alignment with the Earth's axis in as little as a quarter of an hour.[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Milton A. Rothman (1989). Discovering the Natural Laws: The Experimental Basis of Physics. Courier Dover Publications. p. 23-24. ISBN 0-486-26178-6.

reference laws of physics.

- ^ a b Sidney Borowitz; Lawrence A. Bornstein (1968). A Contemporary View of Elementary Physics. McGraw-Hill. p. 138. ASIN B000GQB02A.

- ^ Einstein, A.; Lorentz, H. A.; Minkowski, H.; Weyl, H. (1952). The Principle of Relativity: a collection of original memoirs on the special and general theory of relativity. Courier Dover Publications. p. 111. ISBN 0-486-60081-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Ferraro, Rafael (2007), Einstein's Space-Time: An Introduction to Special and General Relativity, Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 209–210, Bibcode:2007esti.book.....F, ISBN 9780387699462, archived from the original on 7 March 2023, retrieved 2 November 2022

- ^ Ernest Nagel (1979). The Structure of Science. Hackett Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 0-915144-71-9.

- ^ Milutin Blagojević (2002). Gravitation and Gauge Symmetries. CRC Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-7503-0767-6.

- ^ Albert Einstein (1920). Relativity: The Special and General Theory. H. Holt and Company. p. 17.

The Principle of Relativity.

- ^ Richard Phillips Feynman (1998). Six not-so-easy pieces: Einstein's relativity, symmetry, and space-time. Basic Books. p. 73. ISBN 0-201-32842-9.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Armin Wachter; Henning Hoeber (2006). Compendium of Theoretical Physics. Birkhäuser. p. 98. ISBN 0-387-25799-3.

- ^ Ernst Mach (1915). The Science of Mechanics. The Open Court Publishing Co. p. 38.

rotating sphere Mach cord OR string OR rod.

- ^ Lange, Ludwig (1885). "Über die wissenschaftliche Fassung des Galileischen Beharrungsgesetzes". Philosophische Studien. 2.

- ^ Julian B. Barbour (2001). The Discovery of Dynamics (Reprint of 1989 Absolute or Relative Motion? ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 645–646. ISBN 0-19-513202-5.

- ^ L. Lange (1885) as quoted by Max von Laue in his book (1921) Die Relativitätstheorie, p. 34, and translated by Harald Iro (2002). A Modern Approach to Classical Mechanics. World Scientific. p. 169. ISBN 981-238-213-5.

- ^ Milutin Blagojević (2002). Gravitation and Gauge Symmetries. CRC Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-7503-0767-6.

- ^ NMJ Woodhouse (2003). Special relativity. London: Springer. p. 58. ISBN 1-85233-426-6.

- ^ Robert DiSalle (Summer 2002). "Space and Time: Inertial Frames". In Edward N. Zalta (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ^ C Møller (1976). The Theory of Relativity (Second ed.). Oxford UK: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-560539-X. OCLC 220221617.

- ^ For a discussion of the role of fixed stars, see Henning Genz (2001). Nothingness: The Science of Empty Space. Da Capo Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-7382-0610-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Robert Resnick; David Halliday; Kenneth S. Krane (2001). Physics (5th ed.). Wiley. Volume 1, Chapter 3. ISBN 0-471-32057-9.

physics resnick.

- ^ RG Takwale (1980). Introduction to classical mechanics. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 70. ISBN 0-07-096617-6.

- ^ NMJ Woodhouse (2003). Special relativity. London/Berlin: Springer. p. 6. ISBN 1-85233-426-6.

- ^ A Einstein (1950). The Meaning of Relativity. Princeton University Press. p. 58.

- ^ William Geraint Vaughan Rosser (1991). Introductory Special Relativity. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-85066-838-7.

- ^ Richard Phillips Feynman (1998). Six not-so-easy pieces: Einstein's relativity, symmetry, and space-time. Basic Books. p. 50. ISBN 0-201-32842-9.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b See the Principia on line at Andrew Motte Translation

- ^ However, in the Newtonian system the Galilean transformation connects these frames and in the special theory of relativity the Lorentz transformation connects them. The two transformations agree for speeds of translation much less than the speed of light.

- ^ Skinner, Ray (2014). Relativity for Scientists and Engineers (reprinted ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-486-79367-2. Extract of page 27

- ^ LD Landau; LM Lifshitz (1975). The Classical Theory of Fields (4th Revised English ed.). Pergamon Press. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-7506-2768-9.

- ^ Susskind, Leonard; Art Friedman (2017). Special relativity and classical field theory: the theoretical minimum. New York: Hachette UK. Figure 2.1. ISBN 978-0-465-09334-2. OCLC 968771417.

- ^ David Morin (2008). Introduction to Classical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 649. ISBN 978-0-521-87622-3.

acceleration azimuthal Morin.

- ^ Douglas C. Giancoli (2007). Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-13-149508-1.

- ^ A. Einstein, "On the influence of gravitation on the propagation of light Archived 24 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine", Annalen der Physik, vol. 35, (1911) : 898–908

- ^ National Research Council (US) (1986). Physics Through the Nineteen Nineties: Overview. National Academies Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-309-03579-1.

- ^ Allan Franklin (2007). No Easy Answers: Science and the Pursuit of Knowledge. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8229-5968-7.

- ^ Green, Herbert S. (2000). Information Theory and Quantum Physics: Physical Foundations for Understanding the Conscious Process. Springer. p. 154. ISBN 354066517X. Extract of page 154

- ^ Bandyopadhyay, Nikhilendu (2000). Theory of Special Relativity. Academic Publishers. p. 116. ISBN 8186358528. Extract of page 116

- ^ Liddle, Andrew R.; Lyth, David H. (2000). Cosmological Inflation and Large-Scale Structure. Cambridge University Press. p. 329. ISBN 0-521-57598-2. Extract of page 329

- ^ In the Shadow of the Relativity Revolution Archived 20 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine Section 3: The Work of Karl Schwarzschild (2.2 MB PDF-file)

- ^ Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1960). Mechanics (PDF). Pergamon Press. pp. 4–6.

- ^ Amedeo Balbi (2008). The Music of the Big Bang. Springer. p. 59. ISBN 978-3-540-78726-6.

- ^ Abraham Loeb; Mark J. Reid; Andreas Brunthaler; Heino Falcke (2005). "Constraints on the proper motion of the Andromeda Galaxy based on the survival of its satellite M33" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 633 (2): 894–898. arXiv:astro-ph/0506609. Bibcode:2005ApJ...633..894L. doi:10.1086/491644. S2CID 17099715. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ John J. Stachel (2002). Einstein from "B" to "Z". Springer. pp. 235–236. ISBN 0-8176-4143-2.

- ^ Peter Graneau; Neal Graneau (2006). In the Grip of the Distant Universe. World Scientific. p. 147. ISBN 981-256-754-2.

- ^ Henning Genz (2001). Nothingness. Da Capo Press. p. 275. ISBN 0-7382-0610-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ J Garcio-Bellido (2005). "The Paradigm of Inflation". In J. M. T. Thompson (ed.). Advances in Astronomy. Imperial College Press. p. 32, §9. ISBN 1-86094-577-5.

- ^ Wlodzimierz Godlowski; Marek Szydlowski (2003). "Dark energy and global rotation of the Universe". General Relativity and Gravitation. 35 (12): 2171–2187. arXiv:astro-ph/0303248. Bibcode:2003GReGr..35.2171G. doi:10.1023/A:1027301723533. S2CID 118988129.

- ^ Birch, P. (29 July 1982). "Is the Universe rotating?". Nature. 298 (5873): 451–454. Bibcode:1982Natur.298..451B. doi:10.1038/298451a0. S2CID 4343095. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ Gilson, James G. (1 September 2004), Mach's Principle II, arXiv:physics/0409010, Bibcode:2004physics...9010G

- ^ V. I. Arnol'd (1989). Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics. Springer. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-387-96890-2.

- ^ For example, there is no body providing a gravitational or electrical attraction.

- ^ That is, the universality of the laws of physics requires the same tension to be seen by everybody. For example, it cannot happen that the string breaks under extreme tension in one frame of reference and remains intact in another frame of reference, just because we choose to look at the string from a different frame.

- ^ Chatfield, Averil B. (1997). Fundamentals of High Accuracy Inertial Navigation, Volume 174. AIAA. ISBN 9781600864278.

- ^ Kennie, T.J.M.; Petrie, G., eds. (1993). Engineering Surveying Technology (pbk. ed.). Hoboken: Taylor & Francis. p. 95. ISBN 9780203860748.

- ^ Bowditch, Nathaniel (25 September 2002). The American Practical Navigator. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. ISBN 9780939837540.

- ^ "The gyroscope pilots ships & planes". Life. 15 March 1943. pp. 80–83.

Further reading

[edit]- Edwin F. Taylor and John Archibald Wheeler, Spacetime Physics, 2nd ed. (Freeman, NY, 1992)

- Albert Einstein, Relativity, the special and the general theories, 15th ed. (1954)

- Poincaré, Henri (1900). "La théorie de Lorentz et le Principe de Réaction". Archives Neerlandaises. V: 253–78.

- Albert Einstein, On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies, included in The Principle of Relativity, page 38. Dover 1923

- Rotation of the Universe

- Julian B. Barbour; Herbert Pfister (1998). Mach's Principle: From Newton's Bucket to Quantum Gravity. Birkhäuser. p. 445. ISBN 0-8176-3823-7.

- PJ Nahin (1999). Time Machines. Springer. p. 369; Footnote 12. ISBN 0-387-98571-9.

- B Ciobanu, I Radinchi Archived 19 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine Modeling the electric and magnetic fields in a rotating universe Rom. Journ. Phys., Vol. 53, Nos. 1–2, P. 405–415, Bucharest, 2008

- Yuri N. Obukhov, Thoralf Chrobok, Mike Scherfner Archived 9 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine Shear-free rotating inflation Phys. Rev. D 66, 043518 (2002) [5 pages]

- Yuri N. Obukhov On physical foundations and observational effects of cosmic rotation (2000)

- Li-Xin Li Archived 9 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine Effect of the Global Rotation of the Universe on the Formation of Galaxies General Relativity and Gravitation, 30 (1998) doi:10.1023/A:1018867011142

- P Birch Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Is the Universe rotating? Nature 298, 451 – 454 (29 July 1982)

- Kurt Gödel[permanent dead link] An example of a new type of cosmological solutions of Einstein's field equations of gravitation Rev. Mod. Phys., Vol. 21, p. 447, 1949.

External links

[edit]- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry Archived 4 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Animation clip on YouTube showing scenes as viewed from both an inertial frame and a rotating frame of reference, visualizing the Coriolis and centrifugal forces.

- "Is Gravity An Illusion?". PBS Space Time. 3 June 2015. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021 – via YouTube.

Inertial frame of reference

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

An inertial frame of reference is a coordinate system in which Newton's first law of motion holds true, such that an object subject to no net external force remains at rest or continues to move with constant velocity in a straight line.[9][1] Key properties of an inertial frame include the absence of acceleration relative to the distant stars, which approximates a frame at rest with respect to the fixed stars or the cosmic microwave background.[10][11] In such frames, the total linear momentum of an isolated system is conserved, as there are no external forces to alter it.[12] Additionally, fictitious forces—such as centrifugal or Coriolis forces—do not appear, distinguishing inertial frames from non-inertial ones.[13] From a coordinate system perspective, an inertial frame typically employs Cartesian coordinates whose origin and axes move at constant velocity relative to the distant stars (or another inertial frame), ensuring that the laws of motion apply without modification.[2] In classical mechanics, this equates to an unaccelerated frame, where the relative velocity between frames remains constant, preserving the form of physical laws.[9]Historical Development

The concept of an inertial frame emerged in the early 17th century through Galileo Galilei's work on the relativity of motion. In his 1632 book Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Galileo presented the ship thought experiment, illustrating that an observer in a closed cabin below deck on a ship moving at constant velocity over calm waters cannot detect the motion through mechanical experiments, such as dropping a ball or observing a pendulum. This demonstrated that uniform rectilinear motion is indistinguishable from rest, laying the groundwork for the principle that the laws of mechanics remain invariant across frames in relative uniform motion.[14] Isaac Newton advanced this idea significantly in his 1687 Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, where he introduced the notion of absolute space and time as unchanging references. Newton defined inertial frames as those at rest or moving with constant velocity relative to absolute space, in which his first law of motion—the principle of inertia—holds true without external forces. The specific term "inertial frame of reference" (German: Inertialsystem) was coined by German physicist Ludwig Lange in 1885 to replace Newton's definitions of absolute space and time.[1] This formalization tied inertial motion to an absolute framework, enabling the precise prediction of planetary and terrestrial dynamics, and marked a paradigm shift from qualitative Aristotelian views toward quantitative mechanics.[15] By the late 19th century, Ernst Mach challenged Newton's absolute space in his 1883 The Science of Mechanics: A Critical and Historical Account of Its Development. Mach argued that the law of inertia implicitly relies on the distribution of distant matter, such as the fixed stars, rather than an undetectable absolute space, proposing a relational view of motion where acceleration is measured against the bulk of the universe. This critique highlighted the empirical unverifiability of absolute space and influenced the transition away from Newtonian absolutes. Albert Einstein synthesized these developments in his 1905 paper "On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies," which founded special relativity. Einstein redefined inertial frames as those where the laws of physics, including the constancy of the speed of light, are the same for all observers in uniform relative motion, dispensing entirely with absolute space and time. This reformulation resolved inconsistencies between Newtonian mechanics and electromagnetism, extending Galileo's relativity principle to all physical laws and paving the way for modern spacetime concepts.[16]Newtonian Mechanics

Absolute Space and Time

In his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), Isaac Newton introduced the concepts of absolute space and absolute time as foundational elements of classical mechanics. Absolute space is described as an immaterial, infinite entity that exists independently of any objects or relations, remaining always similar and immovable in its own nature. Absolute time, likewise, flows equably without relation to anything external, serving as a universal, uniform measure of durations that is independent of motion or change. These definitions appear in the Scholium following the Definitions in the Principia, where Newton distinguishes them from relative space and time, which are measurable approximations based on sensible objects.[17] Newton's absolute space and time underpin the notion of inertial frames of reference, which are those frames either at rest relative to absolute space or moving at constant velocity with respect to it. In such frames, bodies maintain their state of rest or uniform rectilinear motion unless acted upon by external forces, as articulated in Newton's first law of motion. This absolute framework allows for the identification of true motion as alteration of position in absolute space, contrasting with apparent or relative motions observed from different viewpoints.[18] Philosophically, Newton viewed absolute space as the sensorium of God—an omnipresent, immaterial medium enabling divine perception and action throughout creation— a idea elaborated in the Queries appended to the Latin edition of his Opticks (1706). To demonstrate the reality of absolute rotation, Newton described the famous bucket experiment in the Principia (1687), in which a bucket of water suspended by a rope is spun; the water's surface becomes concave due to centrifugal effects, indicating rotation relative to absolute space even when the water and bucket rotate together, as the concavity persists until equilibrium with absolute space is reached. This argument aimed to show that rotational motion has detectable effects independent of relative motions between bodies.[19][18] Newton's conceptions faced significant philosophical challenges regarding the observability of absolute space. George Berkeley, in his treatise De Motu (1721), critiqued absolute space as an imperceptible, fictitious entity that violates principles of human knowledge, arguing instead that all motion is inherently relative to perceivers or other bodies and that absolute notions introduce unnecessary metaphysics without empirical basis. Building on such relational ideas, Ernst Mach, in Die Mechanik in ihrer Entwicklung (The Science of Mechanics, 1883), denounced absolute space as an unscientific invention, contending that it lacks direct observability and that inertial effects, like those in the bucket experiment, should be understood relative to the fixed stars and distant masses rather than an invisible absolute backdrop.[20]Laws of Motion in Inertial Frames

In an inertial frame of reference, Newton's laws of motion provide the foundational principles for describing the dynamics of physical systems. The first law, also known as the law of inertia, states that every body perseveres in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed thereon./Axioms,or_Laws_of_Motion) In mathematical terms, if the net force acting on a body is zero, then its velocity remains constant: ./Book%3A_University_Physics_I-Mechanics_Sound_Oscillations_and_Waves(OpenStax)/05%3A_Newtons_Laws_of_Motion/5.02%3A_Newtons_First_Law) This law implicitly defines an inertial frame as one in which unforced bodies maintain uniform rectilinear motion, serving as the baseline for all subsequent dynamical descriptions and assuming no acceleration relative to absolute space.[1] The second law quantifies the relationship between force, mass, and acceleration in such frames: the alteration of motion is always proportional to the motive force impressed and takes place along the line of the impressed force./Axioms,or_Laws_of_Motion) For a body of constant mass , this is expressed as , where is the acceleration./Book%3A_University_Physics_I-Mechanics_Sound_Oscillations_and_Waves(OpenStax)/05%3A_Newtons_Laws_of_Motion/5.03%3A_Newtons_Second_Law) This formulation holds precisely only within inertial frames; in non-inertial frames, additional terms would be required to account for the frame's acceleration.[1] Newton's third law asserts that to every action there is always opposed an equal reaction: or, the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal and directed to contrary parts./Axioms,or_Laws_of_Motion) This action-reaction principle implies the conservation of momentum for isolated systems. Consider two bodies interacting, with forces on body 1 due to body 2 and on body 2 due to body 1; the third law requires . Applying the second law, and , so , where is the momentum. Thus, the total momentum remains constant./Book%3A_University_Physics_I-Mechanics_Sound_Oscillations_and_Waves(OpenStax)/05%3A_Newtons_Laws_of_Motion/5.05%3A_Newtons_Third_Law) This derivation follows directly from the third law and extends to systems of multiple bodies, as elaborated in Newton's corollaries to the laws./Axioms,_or_Laws_of_Motion)Special Relativity

Lorentz Transformations

In classical Newtonian mechanics, the Galilean transformations relate coordinates between two inertial frames moving at constant relative velocity along the -axis: , , , and . These transformations assume absolute time and fail to account for the observed constancy of the speed of light in all inertial frames, leading to inconsistencies at relativistic speeds, as evidenced by experiments like the Michelson-Morley null result.[21] To resolve this, Albert Einstein derived the Lorentz transformations in 1905, based on two postulates: the principle of relativity (laws of physics are identical in all inertial frames) and the invariance of the speed of light. The transformations for frames moving at velocity along the -axis are: where is the Lorentz factor. These differ from Galilean transformations by incorporating time dilation and length contraction, ensuring the speed of light remains in both frames.[22] Einstein's derivation assumes linear transformations for homogeneity and isotropy of space-time, then imposes the condition that light propagates at in all directions, solving for the coefficients to yield the above forms; this approach contrasts with the ad hoc electromagnetic origins of earlier Lorentz transformations by Hendrik Lorentz. In the low-speed limit (), , recovering the Galilean transformations as the classical approximation.[22] The Lorentz transformations preserve the space-time interval , introduced by Hermann Minkowski in 1908 to geometrize special relativity, where inertial frames are those in which this Minkowski metric is invariant under Lorentz boosts. This invariance defines the equivalence of inertial frames, as the interval measures proper time and distance independently of the observer's motion.[23] A key consequence is the relativistic velocity addition formula, which replaces the classical : for an object with velocity in one frame, its velocity in a frame moving at relative to the first is along the line of motion. This non-intuitive addition ensures no velocity exceeds , distinguishing relativistic inertial frames from Newtonian ones.[22]Invariance Principles

In special relativity, the principle of relativity asserts that the form of the laws of physics is identical in all inertial frames of reference, meaning no experiment can distinguish one inertial frame from another based on the laws themselves.[24] This principle, central to the theory, ensures that physical predictions remain consistent regardless of uniform translational motion between frames.[24] A key postulate supporting this invariance is the constancy of the speed of light in vacuum, which remains for all observers irrespective of their relative motion or the source's velocity.[24] This invariance implies profound consequences for measurements across frames, such as time dilation, where the elapsed time in a moving frame relates to the proper time by , with for relative speeds .[24] Similarly, it leads to the relativity of simultaneity, where events deemed simultaneous in one inertial frame occur at different times in another moving relative to it, and length contraction, wherein objects appear shortened along the direction of relative motion by a factor of .[24] These effects underscore that there is no absolute rest frame in special relativity; all inertial frames are equivalent, with no privileged frame capable of being identified as "at rest" through physical laws alone.[24] This equivalence contrasts sharply with Newtonian mechanics, which posited an absolute space serving as a universal rest frame.[24] To formalize this framework, Hermann Minkowski introduced the concept of spacetime in 1908, representing inertial frames within a flat four-dimensional geometry where the spacetime interval between events is invariant across frames.[25] In this Minkowski spacetime, the Lorentz transformations serve as the coordinate mappings that preserve the invariance of physical laws and the speed of light.[25]Examples

Translational Motion

In an inertial frame of reference, uniform translational motion exemplifies the principle that objects maintain constant velocity without external forces. A classic illustration involves an observer inside a train moving at constant velocity relative to the ground. If the train travels in a straight line without acceleration, an observer on the platform sees the train moving steadily, while the passenger inside perceives no motion relative to the train's interior; both frames are inertial, as physical laws, such as the behavior of dropped objects, remain unchanged in each.[26][27] A free particle in an inertial frame moves in a straight line at constant speed, embodying the foundational idea that no net force acts upon it. This rectilinear, uniform motion defines the frame's inertial nature, where the particle's trajectory remains unaltered unless perturbed by an external influence.[1][28] Consider two inertial frames moving at a constant relative velocity ; the laws of physics, including descriptions of motion and interactions, are identical in both, ensuring that no experiment can distinguish one as "at rest." This equivalence stems from Newton's first law, which posits that bodies persist in uniform motion in the absence of forces, holding equally in all such frames.[29][30] In everyday scenarios, a car cruising on a highway at steady speed—ignoring minor frictional effects—serves as an intuitive inertial frame for its occupants. Passengers experience no apparent acceleration, and objects like a suspended keychain hang vertically, mirroring the physics observed from the roadside, provided the velocity remains constant.[31]Laboratory and Celestial Frames

In laboratory settings, the frame of reference fixed to the Earth's surface serves as a quasi-inertial frame for many short-duration experiments, where the effects of the planet's rotation and orbital motion can be neglected without significant error. For typical tabletop physics experiments lasting seconds to minutes and spanning distances of meters or less, the fictitious forces arising from Earth's rotation—such as the Coriolis effect—are on the order of 10^{-5} m/s² or smaller at mid-latitudes, far below the precision of most measurements and the dominant gravitational acceleration of approximately 9.8 m/s².[32][33] This approximation holds because the rotational angular velocity of Earth (about 7.3 × 10^{-5} rad/s) induces negligible deviations for non-rotating or slowly moving objects in such confined scales.[33] In celestial mechanics, the barycentric frame centered on the solar system's center of mass provides a close approximation to an inertial frame for describing planetary motions, as the total momentum of the system is zero in this reference. This frame, with its origin at the solar system barycenter (slightly offset from the Sun's center due to planetary influences), aligns well with Kepler's laws, which empirically describe planetary orbits as ellipses with the Sun at one focus, treating the heliocentric view as sufficiently accurate given the Sun's mass dominance (over 99.8% of the solar system's total).[34] Deviations from perfect inertia arise from mutual planetary perturbations, but for two-body approximations like Earth's orbit, the error is minimal, on the order of 10^{-6} in orbital parameters.[34] A more universal inertial reference emerges from the rest frame of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), where the radiation appears isotropic, defining a preferred frame for the observable universe in modern cosmology. This frame, corresponding to the comoving rest frame of the universe's large-scale structure post-recombination, has our solar system moving relative to it at about 370 km/s due to the Milky Way's motion toward the Great Attractor.[35][36] In this frame, local accelerations like Earth's orbital motion around the Sun—yielding a centripetal acceleration of approximately 0.006 m/s²—are small compared to cosmic scales, underscoring its suitability as a baseline inertial system despite the universe's expansion.Non-Inertial Frames

Fictitious Forces

In non-inertial reference frames that accelerate relative to an inertial frame, Newton's second law must be modified to account for the frame's acceleration, resulting in the appearance of fictitious forces that have no physical origin but are necessary to describe the motion of objects as if the frame were inertial. These forces arise because the reference frame itself is undergoing acceleration, such as linear translation or rotation, leading to apparent deviations from the laws of motion observed in inertial frames where no such fictitious terms are required. In a rotating reference frame with constant angular velocity , the most prominent fictitious forces are the centrifugal force and the Coriolis force. The centrifugal force acts radially outward from the axis of rotation and is given by , where is the mass of the object, is its position vector relative to the axis, and the negative sign indicates its direction in the effective equation of motion. This force explains why objects in the rotating frame appear to be pushed away from the center, as seen in a spinning carnival ride where riders feel pressed against the outer wall.[37] The Coriolis force, which depends on the velocity of the object in the rotating frame, is , where is the velocity relative to the rotating frame; it acts perpendicular to both and , deflecting moving objects to the right in the Northern Hemisphere or to the left in the Southern Hemisphere for Earth's rotation. This velocity-dependent force is responsible for the curved paths of projectiles and winds in meteorological models when analyzed from Earth's surface.[38] If the angular velocity is not constant but changing with time, an additional Euler force appears: . This force accounts for the tangential acceleration due to the varying rotation rate, such as in a slowing merry-go-round where objects experience a torque-like push. All three forces—centrifugal, Coriolis, and Euler—emerge from the transformation of coordinates between the inertial and rotating frames, ensuring that Newton's laws hold in their modified form.[39] A classic demonstration of the Coriolis force is the deflection of the Foucault pendulum, where the plane of oscillation rotates over time due to Earth's rotation; in the Northern Hemisphere, the pendulum's swing appears to veer clockwise when viewed from above, with the rate of rotation equal to the local component of Earth's angular velocity. This effect, first observed in 1851, highlights how fictitious forces manifest in everyday scales for slowly rotating systems like Earth.[40]Connection to General Relativity

In general relativity, the concept of an inertial frame of reference is fundamentally tied to the equivalence principle, which posits that the effects of a uniform gravitational field are locally indistinguishable from those of an accelerated reference frame. This principle implies that, in a sufficiently small region of spacetime, an observer in free fall experiences no gravitational effects and thus occupies a local inertial frame. Albert Einstein first articulated this idea in 1907, recognizing it as a key insight for extending special relativity to include gravity, and later formalized it in the 1915-1916 development of general relativity.[41][42] In curved spacetime, as described by general relativity, non-inertial frames in the classical sense approximate the behavior near gravitational sources, but true inertial frames correspond to observers following geodesic paths— the "straightest" possible trajectories in the manifold, analogous to straight lines in flat space. These geodesics represent free fall under gravity, where the only "forces" acting are those encoded in the geometry of spacetime itself. Einstein's field equations, presented in 1915, link the curvature of spacetime to the distribution of mass and energy, ensuring that inertial motion aligns with this geometry.[42] The metric tensor provides the mathematical framework for this generalization, extending the flat Minkowski metric of special relativity to curved spaces, where the spacetime interval is given by Inertial frames locally align with coordinate systems where the metric reduces to the Minkowski form, and observers along geodesics—satisfying the geodesic equation , with Christoffel symbols derived from the metric—experience no proper acceleration. This structure, derived from Einstein's 1916 review, unifies the description of inertial motion across gravitational fields.[42][25] A striking illustration of inertial frames in general relativity appears in black hole spacetimes, such as the Schwarzschild solution for a non-rotating mass. Here, the event horizon at radius (where is the gravitational constant, the mass, and the speed of light) delineates a boundary: inertial observers (those in free fall) crossing it cannot return or send signals to distant regions, as their worldlines inevitably lead to the singularity. Karl Schwarzschild derived this metric in 1916 as the first exact solution to Einstein's equations, highlighting how inertial paths terminate within the horizon for external observers.[43] Unlike the fictitious forces arising in non-inertial frames of classical mechanics, which are artifacts of coordinate choice, general relativity treats gravity not as a force but as the intrinsic geometry of spacetime, with inertial frames defined relative to that curvature. This geometric interpretation, central to Einstein's theory, resolves the equivalence between acceleration and gravitation by embedding both in the same manifold structure.[42]Distinguishing Frames

Theoretical Criteria

One key theoretical criterion for identifying an inertial frame is the conservation of linear momentum in isolated systems. In such frames, the total momentum of a closed system remains constant in the absence of external forces, as Newton's first law dictates uniform motion for free particles. This conservation holds precisely because the frame is non-accelerating, ensuring that no fictitious forces alter the momentum balance.[44] Similarly, the conservation of angular momentum serves as a criterion, manifesting when there is no net external torque on an isolated system. In an inertial frame, the angular momentum vector of the system stays constant, reflecting the absence of rotational fictitious effects that would otherwise introduce spurious torques. This principle underscores the frame's uniformity and isotropy, allowing rotational dynamics to follow Euler's laws without corrections.[45] Another defining feature is the propagation of light, which travels in straight lines at the constant speed in vacuum within inertial frames. This behavior aligns with the null geodesics of flat spacetime, where light rays follow linear paths without deviation due to acceleration or curvature effects local to the frame. In special relativity, this invariance under Lorentz transformations further confirms the frame's inertial nature, as the speed of light remains regardless of the observer's uniform motion.[46][47] Mach's principle provides a relational perspective, positing that inertial frames are determined by the distribution of distant matter in the universe, such that local inertia arises from the average motion relative to remote masses. This view suggests that absolute rotation or acceleration would be detectable against the fixed stars, defining inertia cosmologically. However, post-Einstein developments in general relativity have rendered this principle debated, as the theory permits solutions where local inertia does not strictly depend on global matter distribution.[48] In the framework of general relativity, a formal criterion emerges from spacetime geometry: an inertial frame exists locally where the Riemann curvature tensor vanishes, allowing geodesics to approximate straight lines in Minkowski coordinates at that point. This zero curvature condition ensures that, to first order, the laws of special relativity hold without tidal distortions, though non-zero Riemann components elsewhere signal deviations over extended regions.[49]Practical Applications

In practical applications, accelerometers serve as essential tools for detecting deviations from inertial frames by measuring proper acceleration, which is the acceleration experienced by the device relative to free fall. In an ideal inertial frame, a freely falling accelerometer registers zero proper acceleration, as there are no fictitious forces acting; any non-zero reading indicates acceleration relative to an inertial frame, signaling a non-inertial status such as in accelerating vehicles or rotating platforms. This principle is widely used in inertial navigation systems (INS) to monitor and correct for linear accelerations, ensuring accurate positioning in aerospace and automotive technologies.[50] Gyroscopes complement accelerometers by detecting rotational motion, which renders a frame non-inertial through the introduction of centrifugal and Coriolis effects. These devices measure angular velocity via the precession of a spinning mass or, in optical variants, the Sagnac effect in ring interferometers, where rotation causes a phase shift in counter-propagating light beams. For instance, fiber-optic gyroscopes in aircraft and spacecraft sense Earth's rotation or vehicle turns, allowing real-time adjustments to maintain orientation relative to an inertial reference; nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) gyroscopes achieve even higher precision by observing spin precession in polarized atoms.[51] The Global Positioning System (GPS) exemplifies the use of inertial frame corrections in everyday technology, accounting for Earth's non-inertial motion due to rotation and orbital dynamics through relativistic adjustments. Satellite clocks are pre-adjusted to run slower by approximately 38 μs per day to compensate for special relativistic time dilation from orbital velocity and general relativistic gravitational redshift, ensuring synchronization with ground receivers; additionally, the Sagnac effect from Earth's rotation introduces path delays up to about 133 ns for signals, which are computed dynamically based on receiver position to maintain positioning accuracy within meters. These corrections highlight how non-inertial effects, akin to fictitious forces, must be modeled to achieve reliable satellite-based navigation.[52][53] In high-energy physics, particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN treat the laboratory frame as approximately inertial for analyzing collisions, given the extremely short timescales involved compared to Earth's rotational period. Protons are accelerated to energies of 7 TeV in opposite directions within a 27 km ring, colliding head-on where the center-of-mass frame aligns closely with the lab frame due to symmetric boosts; this setup minimizes non-inertial influences, enabling precise measurements of particle interactions under inertial conditions despite the accelerator's location on a rotating Earth.[54][55] Astronomy leverages distant quasars to establish a deep-space inertial reference frame, as these active galactic nuclei are sufficiently remote that their apparent positions are unaffected by solar system accelerations on human timescales. The International Celestial Reference Frame (ICRF), defined by radio observations of over 3,000 quasars, provides a quasi-inertial basis aligned with the cosmic microwave background; the Gaia mission has enhanced this through optical astrometry, cataloging positions for over 6.6 million quasar candidates in its Data Release 3 (2022) with microarcsecond precision, improving frame stability and enabling better modeling of galactic dynamics and tests of general relativity.[56]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:Space_and_Time