Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

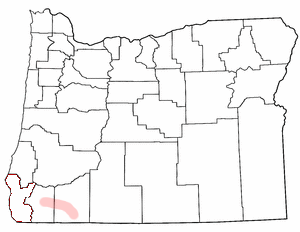

Rogue Valley

View on Wikipedia

The Rogue Valley is a valley region in southwestern Oregon in the United States. Located along the middle Rogue River and its tributaries in Josephine and Jackson counties, the valley forms the cultural and economic heart of Southern Oregon near the California border. The largest communities in the Rogue Valley are Medford, Ashland, and Grants Pass. The most populated part of the Rogue Valley is not along the Rogue proper, but along the smaller Bear Creek tributary.

Key Information

The valley forms a relatively isolated enclave west of the Cascade Range along the north side of the Siskiyou Mountains. It is separated from the nearby coast by a high section of the Southern Oregon Coast Range. The valley is characterized by a mild climate that allows a long growing season, especially for many varieties of fruits, nuts and herbs. A regional manufacturing industry is centered in Medford, the most highly populated area of the valley. In recent years the valley has emerged as a wine-growing region and it is the location of the Rogue Valley AVA (American Viticultural Area). The mild climate and relative isolation have made the valley a popular retirement destination. The community of Ashland is famous for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and Mount Ashland Ski Area. Interstate 5 follows the valley through Ashland, Medford and Grants Pass.

History

[edit]

In the early 19th century, the first European Americans began to pass through the valley, inhabited by the Shasta, Takelma, and Rogue River Athabaskan tribes of Native Americans. The early fur traders named this river the "River of the Rogues". White settlers began to arrive in the valley after the Donation Land Act, which allocated 640 acres (2.6 km2) of land to each married couple. Between 1836 and 1856, the valley was the scene of a series of bloody conflicts between European Americans and the Rogue River tribes. In 1850, gold was discovered[1] on the Rogue River; the next year gold was discovered in the nearby mountains. Early mining activity was centered on the lower Rogue River, on Althouse Creek in Josephine County, and near the now-restored town of Jacksonville, west of Medford. During the gold rush, some $70 million was extracted from the area.

Climate

[edit]| Medford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grants Pass | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ashland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unlike the rest of Western Oregon, because of the rain shadow effect resulting from the close range of the Cascades and Siskiyous, the Rogue Valley is relatively dry when compared to the coast and Portland. Most of the valley has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate. Winters are chilly and rainy, but relatively dry and slightly colder when compared to the rest of western Oregon, with frequent fog, and occasional snow. Summers are hot and sunny, but dry, with low humidity. Temperatures surpass 100 °F (37.8 °C) on an average of 10–15 days during the summer.[citation needed] Because of the combination of heat and dry air, wildfires are a problem during the summer, and frequently, smoke will fill up the valley for weeks, reducing visibility and air quality. On average, the first frost occurs October 22, and the last on May 6.[citation needed] The Rogue Valley is in USDA plant hardiness zones 7–9.[2] Sub-zero temperatures are extremely rare in the valley; the Rogue Valley International-Medford Airport has not recorded such extreme cold weather since December 21, 1990, when the temperature dropped to −2 °F (−18.9 °C).[3]

Due to the valley's generally mild climate, it is used as a region to grow pears, and there are multiple vineyards. Medford has, on average, 175 sunny days per year, compared to 80 on average for the Willamette Valley, and 65 on average for the coast.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Rich Gulch". Southern Oregon History Revised. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ The Associated Press. "Know your Hardiness Zone Map". MailTribune.com.

- ^ "Weather History for Medford, OR – Weather Underground".