Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

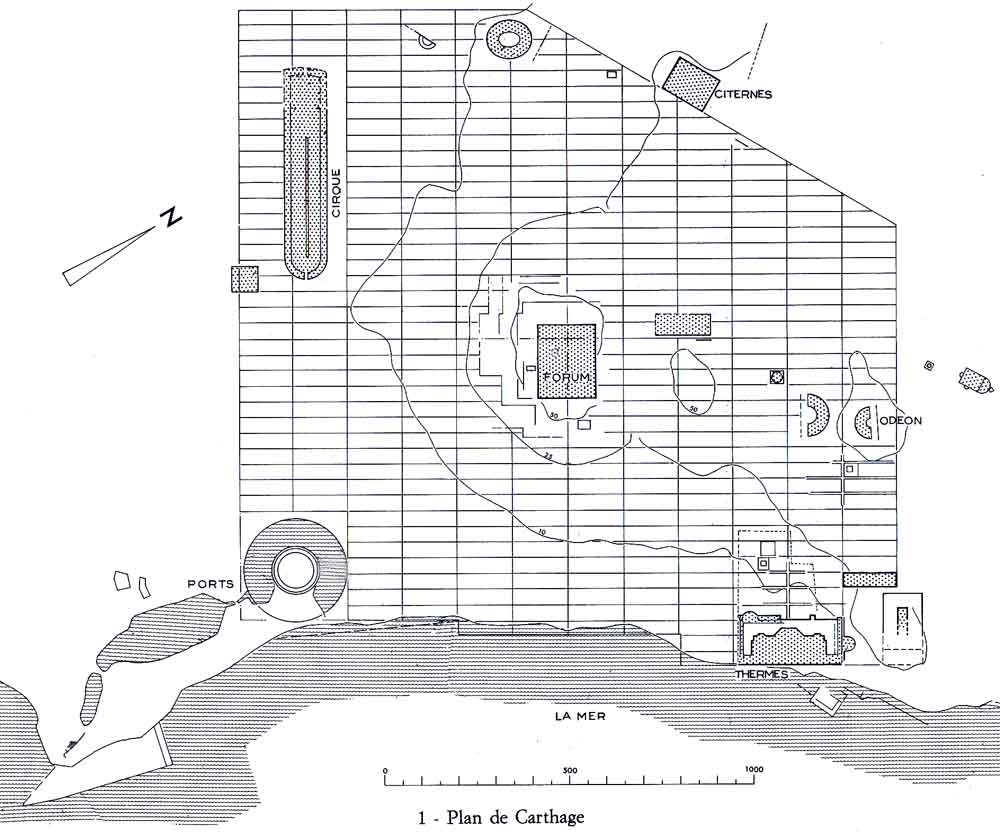

Roman Carthage

View on Wikipedia

Roman Carthage was an important city in ancient Rome, located in modern-day Tunisia. Approximately 100 years after the destruction of Punic Carthage in 146 BC, a new city of the same name (Latin Carthāgō) was built on the same land by the Romans in the period from 49 to 44 BC. By the 3rd century, Carthage had developed into one of the largest cities of the Roman Empire, with a population of several hundred thousand.[1] It was the center of the Roman province of Africa, which was a major breadbasket of the empire. Carthage briefly became the capital of a usurper, Domitius Alexander, in 308–311. Conquered by the Vandals in 439,[2] Carthage served as the capital of the Vandal Kingdom for a century. Re-conquered by the Eastern Roman Empire in 533–534, it continued to serve as an Eastern Roman regional center, as the seat of the praetorian prefecture of Africa (after 590 the Exarchate of Africa).

The city was sacked and destroyed by Umayyad Arab forces after the Battle of Carthage in 698 to prevent it from being reconquered by the Byzantine Empire.[3] A fortress on the site was garrisoned by Muslim forces[4] until the Hafsid period, when it was captured by Crusaders during the Eighth Crusade. After the withdrawal of the Crusaders, the Hafsids decided to destroy the fortress to prevent any future use by a hostile power.[5] Roman Carthage was used as a source of building materials for Kairouan and Tunis in the 8th century.[6]

History

[edit]

Foundation

[edit]

After the Roman conquest of Carthage, its nearby rival Utica, a Roman ally, was made capital of the region and for a while replaced Carthage as the leading centre of Punic trade and leadership. It had the advantageous position of being situated on the outlet of the Medjerda River, Tunisia's only river that flowed all year long. However, grain cultivation in the Tunisian mountains caused large amounts of silt to erode into the river. This silt accumulated in the harbour until it became useless, and so Rome looked for a new harbour town.

By 122 BC, Gaius Gracchus had founded a short-lived Roman colony, called Colonia Junonia. The purpose was to obtain arable lands for impoverished farmers. The Senate abolished the colony some time later, to undermine Gracchus' power.

After this failed effort, Carthage was rebuilt by Julius Caesar in the period from 49 to 44 BC, with the official name Colonia Iulia Concordia Carthago.[7] By the first century, it had grown to be the second-largest city in the western half of the Roman Empire. The geographer Strabo wrote that when the third Punic War began in 149 BC, the Carthaginians ruled 300 cities in Libya and 700,000 people lived in Carthage. Dexter Hoyos writes that it was physically impossible in any period of its history for that many people to live within its walls.[8] According to Hoyos, the population of Roman Carthage and its surrounding territory would have been around 575,000 in AD 149.[9] It was the centre of the Roman province of Africa, which was a major breadbasket of the empire. Among its major monuments was an amphitheatre. The temple of Juno Caelestis, dedicated to the City Protector Goddess Juno Caelestis, was one of the biggest building monuments of Carthage, and became a holy site for pilgrims from all Northern Africa and Spain.[10]

Early Christianity

[edit]Carthage became a centre of early Christianity. In the first of a string of rather poorly reported councils at Carthage a few years later, 70 bishops attended. Tertullian later broke with the mainstream that was increasingly represented in the West by the primacy of the Bishop of Rome, but a more serious rift among Christians was the Donatist controversy, against which Augustine of Hippo spent much time and parchment arguing. At the Council of Carthage (397), the biblical canon for the western Church was confirmed. The Christians at Carthage conducted persecutions against the pagans, during which the pagan temples, including the Temple of Juno Caelesti, were destroyed.[11]

The great fire of the second century, which swept through the capital of the governor of the province, made it possible to develop a hilly area of the city as part of an important urban planning project. A vast district of luxurious dwellings, including the "Villa de la volière", was built on this occasion. A circular monument, which was excavated during the UNESCO campaign, called "rotonde sur podium carré",[12] is sometimes dated to the Christian period and identified by some researchers as a mausoleum.[13] A huge inscription to Aesculapius was found nearby, which suggests that the Punic temple of Eshmun was located on this site. Texts indicate that the Romans built the temple to the corresponding deity of their pantheon on the same site.[12] The last fundamental element of the building program is a large leisure area, with a theatre dating from the second century and an odeon built in the third century. According to Victor de Vita, the whole area was destroyed by the Vandals. However, a remaining population lived there and a settlement persisted in the ruins.

Vandal period

[edit]

The Vandals under Gaiseric landed at the Roman province of Africa in 429,[14] either at the request of Bonifacius, a Roman general and the governor of the Diocese of Africa,[15] or as migrants in search of safety. They subsequently fought against the Roman forces there and by 435[citation needed] had defeated the Roman forces in Africa and established the Vandal Kingdom.[12] As an Arian, Gaiseric was considered a heretic by the Catholic Christians, but a promise of religious toleration might have caused the city's population to accept him.

The 5th-century Roman bishop Victor Vitensis mentions in Historia Persecutionis Africanae Provincia that the Vandals destroyed parts of Carthage, including various buildings and churches.[16] Once in power, the ecclesiastical authorities were persecuted, the locals were aggressively taxed, and naval raids were routinely launched on Romans in the Mediterranean.[17]

Byzantine period

[edit]After two failed attempts by Majorian and Basiliscus to recapture the city in the 5th century, the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire, using the deposition of Gaiseric's grandson Hilderic by his cousin Gelimer as a "casus belli", finally subdued the Vandals in the Vandalic War of 533–534, the Roman general Belisarius, accompanied by his wife Antonina, made his formal entry into Carthage in October 533. Thereafter, for the next 165 years, the city was the capital of Byzantine North Africa, first organised as the praetorian prefecture of Africa, which later became the Exarchate of Africa during the emperor Maurice's reign. Along with the Exarchate of Ravenna, these two regions were the western bulwarks of the Byzantine Empire, all that remained of its power in the West. In the early seventh century Heraclius the Elder, the Exarch of Africa, rebelled against the Byzantine emperor Phocas, whereupon his son Heraclius succeeded to the imperial throne.

Islamic conquest

[edit]The Exarchate of Africa first faced Muslim expansion from Egypt in 647, but without lasting effect. A more protracted campaign lasted from 670 to 683 but ended in a Muslim defeat in the battle of Vescera. Captured by the Muslims in 695, it was recaptured by the Byzantines in 697, but was finally conquered in 698 by the Umayyad forces of Hassan ibn al-Nu'man. Fearing that the Eastern Roman Empire might reconquer it, the Umayyads decided to destroy Roman Carthage in a scorched earth policy and establish their centre of government further inland at Tunis. The city walls were torn down, the water supply cut off, the agricultural land ravaged and its harbours made unusable.[3] The destruction of the Roman Carthage and the Exarchate of Africa marked a permanent end to Roman rule in the region, which had largely been in place since the 2nd century BC.

It is visible from archaeological evidence that the town of Carthage continued to be occupied, particularly the neighbourhood of Bjordi Djedid. The Baths of Antoninus continued to function in the Arab period and the historian Al-Bakri stated that they were still in good condition. They also had production centres nearby. It is difficult to determine whether the continued habitation of some other buildings belonged to Late Byzantine or Early Arab period. The Bir Ftouha church might have continued to remain in use though it is not clear when it became uninhabited.[4] Constantine the African was born in Carthage.[18]

The fortress of Carthage continued to be used by the Muslims until the Hafsid era and was captured in 1270 by Christian forces during the Eighth Crusade. After the withdrawal of the Crusaders, Muhammad I al-Mustansir decided to completely destroy it to prevent a repetition.[5]

Rediscovery

[edit]The ruins of Carthage were rediscovered at the end of the 19th century.[19] The Odeon was excavated in 1900–1901,[20] and the amphitheatre was excavated in 1904.

Amphitheatre

[edit]Odeon Hill

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

Odeon Hill, located to the north-east of the archaeological site of Carthage, is the site of numerous Roman ruins, including the theatre, the odeon, and the park of the Roman villas. The park includes the villa of the aviary, the best preserved Roman villa of the site of Carthage.

The House of the Horses contains a mosaic of more than fifty circus horses, bordered by hunting scenes.[21]

The Odeon Hill has its name due to a misidentification of the building which was thought to be the Odeon, known to exist from Tertullian, but what tuned out to be a theatre.[20] Odeon hill and the park of the Roman villas are located to the east of the Roman colony of Carthage, and to the north of the park of the Baths of Antoninus. On its outskirts is now located the area of the presidential palace in the south, while in the north the Mâlik ibn Anas mosque has been built.

Theatre

[edit]

Tertullian mentions in his introduction to the Florides[22] the richness of the decoration, the splendour of the marbles of the cavea, the parquet floor of the proscenium and the haughty beauty of the pillars.[23] There was a colonnade of marble and porphyry on the frons scænae, numerous statues and quality epigraphic ornaments. The theatre extends over an area equivalent of about four blocks and dates probably to the times of Augustus. By size it is the second largest Roman theatre in Africa, only the one in Utica is larger.[20]

Fragments of inscriptions found in the theatre refer to repairs made in the fourth century.[24]

The theatre is a mixture of Greek and Roman theatre: the tiers are supported by a system of vaults, but take advantage of the slope of the hill.[25] The cavea consisted of sections with tiers separated by stairs. The orchestra, with its more comfortable movable seats, was intended for VIP spectators. The pulpitum was a wall separating the orchestra from the stage, while the frons scænae formed the backdrop to the building. The odeon was entirely built, as it did not take advantage of the topography.

There are very few Roman remains of the stands in the present building. The theatre was renovated and since 1964 it is the site of the International Festival of Carthage.[26] The semicircular walls also date from the early 20th century when it was used for costume production.

Odeon

[edit]

Only traces of substructures of the Odeon remain, barely cleared at the beginning of the 20th century. It was rediscovered by Paul Gauckler who lead the excavations between 1900 and 1901.[20] The Odeon was mentioned by the Christian theologist Tertullian and is where the Roman Emperor of African origin Septimus Severus shall have awarded the prize for the winner of the literary competition.[27] The Odeon, which is considered to be the largest Roman Odeon, lies adjacent to the southern theatre and occupies three city blocks. It had a seating capacity of about 20,000 spectators and it was not assumed to be an Odeon were it not for the inscription ODEVM discovered in a cistern under the stage. In comparison, the second largest Roman Odeon in Athens had a seating capacity of 5,000.[20]

Excavations took place again between 1994-2000 by researchers from the School of Architecture of the University of Waterloo in Ontario and the Trinity University in Texas.[20] Although the site is located in a non aedificandi zone, it is now situated in the immediate vicinity of the Mâlik ibn Anas Mosque. The building, which stood against the theater and was built entirely above ground level, had semi-circular corridors for the circulation of visitors. Tertullian mentions the discovery of burial sites during the construction of the building. Timothy Barnes assumed it to have been built around 200 BC.[20]

Roman villas

[edit]

The relics of the villas are in a mediocre state, except for those of the villa of the aviary. The main interest of the district consists in the vision of a neighbourhood of the Colonia Iulia Carthago, organised in insulae or small islands of 35 meters by 141 meters.

The second-century district has orthogonal streets, "successive tiers crammed into the sides of the hill";[28] the upper tier is located in the ground, the lower tier opens onto the street above the lower tier. The flats were located on the upper floor, with the shops occupying the ground floor at street level.

The villa is the main feature of the park, due to the quality of the restoration carried out in the 1960s.[29] The name of the villa comes from the mosaic of the aviary, marked by the presence of birds among the foliage,[28] which occupies the garden, in the centre of the viridarium, the heart of a square courtyard framed by a portico decorated with pink marble pillars.

To the southwest is a terrace that opens onto the street. To the west, a vaulted gallery also serves as a relief from the pressure of the ground, while the building's atrium is located to the east. To the north are all the prestige rooms, the ceremonial flats, the laraire and the vestibule.

Upstairs were the baths and shops. On the upper floor were the private flats of the owners, with shops under the terraced portico. Below the cryptoporticus was a weatherproof promenade.

Baths of Antoninus

[edit]

The Baths of Antoninus or Baths of Carthage are the largest set of Roman thermae built on the African continent and one of three largest built in the Roman Empire. They are the largest outside mainland Italy.[30] The baths are also the only remaining Thermae of Carthage that dates back to the Roman Empire's era. The baths were built during the reign of Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius.[31] The baths continued to function in the Arab period: the historian Al-Bakri stated that they were still in good condition.[citation needed]

The baths are at the South-East of the archaeological site, near the presidential Carthage Palace. The archaeological excavations started during the Second World War and concluded by the creation of an archaeological park for the monument. It is also one of the most important landmarks of Tunisia.[citation needed]

Circus

[edit]

The Circus of Carthage was modelled on the Circus Maximus in Rome. Measuring more than 470 m in length and 30 m in width,[32] it could house up to 45,000 spectators, roughly one third of the Circus Maximus, and was used for chariot racing.

The building appears to have been constructed sometime around 238 AD, and was used for several years before its official dedication.

Remains from the Circus Maximus, specifically the marble "spina" (a dividing barrier) were used in the Circus of Carthage, as well as the Circus of Maxentius and the city of Vienne located in France.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Likely the fourth city in terms of population during the imperial period, following Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, in the 4th century also surpassed by Constantinople; also of comparable size were Ephesus, Smyrna and Pergamum. Stanley D. Brunn, Maureen Hays-Mitchell, Donald J. Zeigler (eds.), Cities of the World: World Regional Urban Development, Rowman & Littlefield, 2012, p. 27

- ^ Peter Heather (2010). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History. Pan Macmillan. p. 402. ISBN 9780330529839.

- ^ a b C. Edmund Bosworth (2008). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Brill Academic Press. p. 536. ISBN 978-9004153882.

- ^ a b Anna Leone (2007). Changing Townscapes in North Africa from Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest. Edipuglia srl. pp. 179–186. ISBN 9788872284988.

- ^ a b Thomas F. Madden; James L. Naus; Vincent Ryan, eds. (2018). Crusades – Medieval Worlds in Conflict. Oxford University Press. pp. 113, 184. ISBN 978-0-19-874432-0.

- ^ Colum Hourihane (2012). The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539536-5.

- ^ Hoyos, Dexter (2020). Carthage: A Biography. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-000-32816-5.

- ^ Hoyos, Dexter (2020). Carthage: A Biography. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-000-32816-5.

Only one population figure for the city of Carthage survives and nobody believes it. The Augustan geographer Strabo wrote that in 149 bc, when the third Punic War opened, the Carthaginians ruled 300 cities in Libya and 700,000 people lived in the city. Since by then their territories had been drastically cut back by the acquisitive Numidian king Masinissa, the 300 'cities' must at best have been mostly villages and hamlets. Not only that, but it was a physical impossibility at any period for nearly three-quarters of a million persons to reside within Carthage's walls.

- ^ Hoyos, Dexter (2005). Hannibal's Dynasty: Power and Politics in the Western Mediterranean, 247-183 BC. Psychology Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-415-35958-0.

- ^ McHugh, J. S. (2015). The Emperor Commodus: God and Gladiator. (n.p.): Pen & Sword Books.

- ^ Brent D. Shaw (September 2011). Sacred Violence: African Christians and Sectarian Hatred in the Age of Augustine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521196055. Archived from the original on 2022-11-26. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ a b c Picard (1951, p. 42)

- ^ Ennabli & Slim (1993, p. 55)

- ^ Roger Collins. "Vandal Africa, 429–533", XIV. Cambridge University Press. p. 124.

- ^ Procopius Wars 3.5.23–24 in Collins 2004, p. 124

- ^ Anna Leone (2007). Changing Townscapes in North Africa from Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest. Edipuglia srl. p. 155. ISBN 9788872284988.

- ^ Thomas Brown; George Holmes (1988). The Oxford History of Medieval Europe. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. p. 3.

- ^ Charles Singer (29 October 2013). A Short History of Science to the Nineteenth Century. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486169286.

- ^ "The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, CABANES ("Ildum") Castellón, Spain., CARCASO (Carcassonne) Gallia Narbonensis, Aude, France., CARTHAGE Tunisia". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wells, Colin M. (2007). "A Cuckoo in the Nest: The Roman Odeon at Carthage in its Urban Context". American Journal of Ancient History. New Series. 3–4: 131–135. doi:10.31826/9781463213930-007. ISBN 978-1-4632-1393-0.

- ^ Katherine M. D. Dunbabin (1999). Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780521002301.

- ^ Ennabli & Slim (1993, p. 50)

- ^ Picard & (1951, p. 43)

- ^ Ennabli & Slim (1993, p. 48)

- ^ Ennabli & Slim (1993, p. 49)

- ^ Roua Khlifi (14 August 2015). "Carthage International Festival continues to shine from Roman amphitheatre". Arab Weekly. Retrieved 2023-01-20.

- ^ "Overview". www.tunisiepatrimoine.tn (in Danish). 2 October 2022. Retrieved 2023-01-20.

- ^ a b Picard (1951, p. 44)

- ^ Ennabli & Slim (1993, pp. 51–52)

- ^ "Where climate change threatens ancient sites and modern livelihoods". The Christian Science Monitor. 10 February 2020.

- ^ "How many ancient cities do you know? Quiz answers". TheGuardian.com. 15 November 2013.

- ^ Humphrey, J.H. (1986). Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. University of California Press. p. 446. ISBN 9780520049215. Retrieved 2015-08-14.

- ^ Peck, Harry Thurston (1897). "Harper's Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities".

- Sources

- Ennabli, Abdelmajid; Slim, Hédi (1993). Carthage le site archéologique (in French). Paris: Cérès. p. 91. ISBN 978-9973700834.

- Picard, Colette (1951). Carthage (in French). Paris: Les Belles Lettres. p. 100.

- Heather, Peter (2004). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History. Pan Macmillan. p. 402

Further reading

[edit]- Auguste Audollent (1901), Carthage Romaine, 146 avant Jésus-Christ — 698 après Jésus-Christ, Paris.

- Ernest Babelon, Carthage, Paris (1896).

- S. Raven (2002), Rome in Africa, 3rd ed.