Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sampi

View on Wikipedia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Greek alphabet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diacritics and other symbols | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sampi (modern: ϡ; ancient shapes: ![]() ,

, ![]() ) is an archaic letter of the Greek alphabet. It was used as an addition to the classical 24-letter alphabet in some eastern Ionic dialects of ancient Greek in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, to denote some type of a sibilant sound, probably [ss] or [ts], and was abandoned when the sound disappeared from Greek.

) is an archaic letter of the Greek alphabet. It was used as an addition to the classical 24-letter alphabet in some eastern Ionic dialects of ancient Greek in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, to denote some type of a sibilant sound, probably [ss] or [ts], and was abandoned when the sound disappeared from Greek.

It later remained in use as a numeral symbol for 900 in the alphabetic ("Milesian") system of Greek numerals. Its modern shape, which resembles a π inclining to the right with a longish curved cross-stroke, developed during its use as a numeric symbol in minuscule handwriting of the Byzantine era.

Its current name, sampi, originally probably meant "san pi", i.e. "like a pi", and is also of medieval origin. The letter's original name in antiquity is not known. It has been proposed that sampi was a continuation of the archaic letter san, which was originally shaped like an M and denoted the sound [s] in some other dialects. Besides san, names that have been proposed for sampi include parakyisma and angma, while other historically attested terms for it are enacosis, sincope, and o charaktir.

Alphabetic sampi

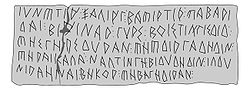

[edit]As an alphabetic letter denoting a sibilant sound, sampi (shaped ![]() ) was mostly used between the middle of the 6th and the middle of the 5th centuries BC,[1] although some attestations have been dated as early as the 7th century BC. It has been attested in the cities of Miletus,[2] Ephesos, Halikarnassos, Erythrae, Teos (all situated in the region of Ionia in Asia Minor), in the island of Samos, in the Ionian colony of Massilia,[3] and in Kyzikos (situated farther north in Asia Minor, in the region of Mysia). In addition, in the city of Pontic Mesembria, on the Black Sea coast of Thrace, it was used on coins, which were marked with the abbreviation of the city's name, spelled "ΜΕͲΑ".[1]

) was mostly used between the middle of the 6th and the middle of the 5th centuries BC,[1] although some attestations have been dated as early as the 7th century BC. It has been attested in the cities of Miletus,[2] Ephesos, Halikarnassos, Erythrae, Teos (all situated in the region of Ionia in Asia Minor), in the island of Samos, in the Ionian colony of Massilia,[3] and in Kyzikos (situated farther north in Asia Minor, in the region of Mysia). In addition, in the city of Pontic Mesembria, on the Black Sea coast of Thrace, it was used on coins, which were marked with the abbreviation of the city's name, spelled "ΜΕͲΑ".[1]

Sampi occurs in positions where other dialects, including written Ionic, normally have double sigma (σσ), i.e. a long /ss/ sound. Some other dialects, particularly Attic Greek, have ττ (long /tt/) in the same words (e.g. θάλασσα vs. θάλαττα 'sea', or τέσσαρες vs. τέτταρες 'four'). The sounds in question are all reflexes of the proto-Greek consonant clusters *[kj], *[kʰj], *[tj], *[tʰj], or *[tw]. It is therefore believed that the local letter sampi was used to denote some kind of intermediate sound during the phonetic change from the earlier plosive clusters towards the later /s/ sound, possibly an affricate /ts/, forming a triplet with the Greek letters for /ks/ and /ps/.[4][5]

Among the earliest known uses of sampi in this function is an abecedarium from Samos dated to the mid-7th century BC. This early attestation already bears witness to its alphabetic position behind omega (i.e. not the position of san), and it shows that its invention cannot have been much later than that of omega itself.[2][3]

The first known use of alphabetic sampi in writing native Greek words is an inscription found on a silver plate in Ephesus, which has the words "τέͳαρες" ("four") and "τεͳαράϙοντα" ("forty") spelled with sampi (cf. normal spelling Ionic "τέσσαρες/τεσσαράκοντα" vs. Attic τέτταρες/τετταράκοντα). It can be dated between the late 7th century and mid 6th century BC.[6][7] An inscription from Halicarnassus[8] has the names "Ἁλικαρναͳέ[ω]ν" ("of the Halicarnassians") and the personal names "Ὀαͳαͳιος" and "Π[α]νυάͳιος". All of these names appear to be of non-Greek, local origin, i.e. Carian.[9] On a late 6th century bronze plate from Miletus dedicated to the sanctuary of Athena at Assesos, the spelling "τῇ Ἀθηνάηι τῇ Ἀͳησίηι" ("to Athena of Assessos") has been identified.[2][10] This is currently the first known instance of alphabetic sampi in Miletus itself, commonly assumed to be the birthplace of the numeral system and thus of the later numeric use of sampi.

It has been suggested that there may be an isolated example of the use of alphabetic sampi in Athens. In a famous painted black figure amphora from c.615 BC, known as the "Nessos amphora", the inscribed name of the eponymous centaur Nessus is rendered in the irregular spelling "ΝΕΤΟΣ" (Νέτος). The expected regular form of the name would have been either Attic "Νέττος" – with a double "τ" – or Ionic "Νέσσος". Traces of corrections that are still visible underneath the painted "Τ" have led to the conjecture that the painter originally wrote Νέͳος, with sampi for the σσ/ττ sound.[11][12]

Pamphylian sampi

[edit]A letter similar to Ionian sampi, but of unknown historical relation with it, existed in the highly deviant local dialect of Pamphylia in southern Asia Minor. It was shaped like ![]() . According to Brixhe[13] it probably stood for the sounds /s/, /ss/, or /ps/. It is found in a few inscriptions in the cities of Aspendos and Perge as well as on local coins. For instance, an inscription from Perge dated to around 400 BC reads: Ͷανά

. According to Brixhe[13] it probably stood for the sounds /s/, /ss/, or /ps/. It is found in a few inscriptions in the cities of Aspendos and Perge as well as on local coins. For instance, an inscription from Perge dated to around 400 BC reads: Ͷανά![]() αι Πρειίαι Κλεμύτας Λϝαράμυ Ͷασιρϝο̄τας ἀνέθε̄κε (="Vanássāi Preiíāi Klemútas Lwarámu Vasirwōtas anéthēke", "Klemutas the vasirwotas, son of Lwaramus, dedicated this to the Queen of Perge").[14] The same title "Queen of Perge", the local title for the goddess Artemis, is found on coin legends: Ͷανά

αι Πρειίαι Κλεμύτας Λϝαράμυ Ͷασιρϝο̄τας ἀνέθε̄κε (="Vanássāi Preiíāi Klemútas Lwarámu Vasirwōtas anéthēke", "Klemutas the vasirwotas, son of Lwaramus, dedicated this to the Queen of Perge").[14] The same title "Queen of Perge", the local title for the goddess Artemis, is found on coin legends: Ͷανά![]() ας Πρειιας.[15] As Ͷανά

ας Πρειιας.[15] As Ͷανά![]() α is known to be the local feminine form of the archaic Greek noun ἄναξ/ϝάναξ, i.e. (w)anax ("king"), it is believed that the

α is known to be the local feminine form of the archaic Greek noun ἄναξ/ϝάναξ, i.e. (w)anax ("king"), it is believed that the ![]() letter stood for some type of sibilant reflecting Proto-Greek */ktj/.

letter stood for some type of sibilant reflecting Proto-Greek */ktj/.

Numeric sampi

[edit]In the alphabetic numeral system, which was probably invented in Miletus and is therefore sometimes called the "Milesian" system, there are 27 numeral signs: the first nine letters of the alphabet, from alpha (A) to theta (Θ) stand for the digits 1–9; the next nine, beginning with iota (Ι), stand for the multiples of ten (10, 20, etc. up to 90); and the last nine, beginning with rho (Ρ), stand for the hundreds (100 – 900). For this purpose, the 24 letters of the standard classical Greek alphabet were used with the addition of three archaic or local letters: digamma/wau (Ϝ, ![]() , originally denoting the sound /w/) for "6", koppa (Ϙ, originally denoting the sound /k/) for "90", and sampi for "900". While digamma and koppa were retained in their original alphabetic positions inherited from Phoenician, the third archaic Phoenician character, san/tsade (Ϻ, denoting an [s] sound), was not used in this way. Instead, sampi was chosen, and added at the end of the system, after omega (800).

, originally denoting the sound /w/) for "6", koppa (Ϙ, originally denoting the sound /k/) for "90", and sampi for "900". While digamma and koppa were retained in their original alphabetic positions inherited from Phoenician, the third archaic Phoenician character, san/tsade (Ϻ, denoting an [s] sound), was not used in this way. Instead, sampi was chosen, and added at the end of the system, after omega (800).

From this, it has been concluded that the system must have been invented at a time and place when digamma and koppa were still either in use or at least still remembered as parts of the alphabetic sequence, whereas san had either already been forgotten, or at least was no longer remembered with its original alphabetic position. In the latter case, according to a much debated view, sampi itself may in fact have been regarded as being san, but with a new position in the alphabet.

The dating of the emergence of this system, and with it of numeric sampi, has been the object of much discussion. At the end of the 19th century, authors such as Thompson[16] placed its full development only in the 3rd century BC. Jeffery[1] states that the system as a whole can be traced much further back, into the 6th century BC. An early, though isolated, instance of apparent use of alphabetic Milesian numerals in Athens occurs on a stone inscribed with several columns of two-digit numerals, of unknown meaning, dated from the middle of the 5th century BC.[17][18]

While the emergence of the system as a whole has thus been given a much earlier dating than was often assumed earlier, actual occurrences of the letter sampi in this context have as yet not been found in any early examples. According to Threatte, the earliest known use of numeric sampi in a stone inscription occurs in an inscription in Magnesia from the 2nd century BC, in a phrase denoting a sum of money ("δραχ(μὰς) ϡʹ)[19] but the exact numeric meaning of this example is disputed.[12] In Athens, the first attestation is only from the beginning of the 2nd century AD, again in an inscription naming sums of money.[20][21]

Earlier than the attestations in the full function as a numeral are a few instances where sampi was used in Athens as a mark to enumerate sequences of things in a set, along with the 24 other letters of the alphabet, without implying a specific decimal numeral value. For instance, there is a set of 25 metal tokens, each stamped with one of the letters from alpha to sampi, which are dated to the 4th century BC and were probably used as identification marks for judges in the courts of the Athenian democracy.[6][22]

In papyrus texts from the Ptolemaic period onwards, numeric sampi occurs with some regularity.[21]

At an early stage in the papyri, the numeral sampi was used not only for 900, but, somewhat confusingly, also as a multiplicator for 1000, since a way of marking thousands and their multiples was not yet otherwise provided by the alphabetic system. Writing an alpha over sampi (![]() or, in a ligature,

or, in a ligature, ![]() ) meant "1×1000", a theta over sampi (

) meant "1×1000", a theta over sampi (![]() ) meant "9×1000", and so on. In the examples cited by Gardthausen, a slightly modified shape of sampi, with a shorter right stem (

) meant "9×1000", and so on. In the examples cited by Gardthausen, a slightly modified shape of sampi, with a shorter right stem (![]() ), is used.[23] This system was later simplified into one where the thousands operator was marked just as a small stroke to the left of the letter (͵α = 1000).

), is used.[23] This system was later simplified into one where the thousands operator was marked just as a small stroke to the left of the letter (͵α = 1000).

Glyph development

[edit]In early stone inscriptions, the shape of sampi, both alphabetic and numeric, is ![]() . Square-topped shapes, with the middle vertical stroke either of equal length with the outer ones

. Square-topped shapes, with the middle vertical stroke either of equal length with the outer ones ![]() or longer

or longer ![]() , are also found in early papyri. This form fits the earliest attested verbal description of the shape of sampi as a numeral sign in the ancient literature, which occurs in a remark in the works of the 2nd-century AD physician Galen. Commenting on the use of certain obscure abbreviations found in earlier manuscripts of Hippocrates, Galen says that one of them "looks like the way some people write the sign for 900", and describes this as "the shape of the letter Π with a vertical line in the middle" ("ὁ τοῦ π γραμμάτος χαρακτὴρ ἔχων ὀρθίαν μέσην γραμμὴν, ὡς ἔνιοι γράφουσι τῶν ἐννεακοσίων χαρακτῆρα").[24]

, are also found in early papyri. This form fits the earliest attested verbal description of the shape of sampi as a numeral sign in the ancient literature, which occurs in a remark in the works of the 2nd-century AD physician Galen. Commenting on the use of certain obscure abbreviations found in earlier manuscripts of Hippocrates, Galen says that one of them "looks like the way some people write the sign for 900", and describes this as "the shape of the letter Π with a vertical line in the middle" ("ὁ τοῦ π γραμμάτος χαρακτὴρ ἔχων ὀρθίαν μέσην γραμμὴν, ὡς ἔνιοι γράφουσι τῶν ἐννεακοσίων χαρακτῆρα").[24]

From the time of the earliest papyri, the square-topped forms of handwritten sampi alternate with variants where the top is rounded (![]() ,

, ![]() ) or pointed (

) or pointed (![]() ,

, ![]() ).[25][26] The rounded form

).[25][26] The rounded form ![]() also occurs in stone inscriptions in the Roman era.[21] In the late Roman period, the arrow-shaped or rounded forms are often written with a loop connecting the two lines at the right, leading to the "ace-of-spades" form

also occurs in stone inscriptions in the Roman era.[21] In the late Roman period, the arrow-shaped or rounded forms are often written with a loop connecting the two lines at the right, leading to the "ace-of-spades" form ![]() , or to

, or to ![]() . These forms, in turn, occasionally have another decorative stroke added on the left (

. These forms, in turn, occasionally have another decorative stroke added on the left (![]() ). It can be found attached in several different ways, from the top (

). It can be found attached in several different ways, from the top (![]() ) or the bottom (

) or the bottom (![]() ).[26] From these shapes, finally, the modern form of sampi emerges, beginning in the 9th century, with the two straight lines becoming more or less parallel (

).[26] From these shapes, finally, the modern form of sampi emerges, beginning in the 9th century, with the two straight lines becoming more or less parallel (![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ).

).

In medieval western manuscripts describing the Greek alphabet, the arrowhead form is sometimes rendered as ![]() .[27]

.[27]

Origins

[edit]Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, many authors have assumed that sampi was essentially a historical continuation of the archaic letter san (Ϻ), the M-shaped alternative of sigma (Σ) that formed part of the Greek alphabet when it was originally adopted from Phoenician. Archaic san stood in an alphabetic position between pi (Π) and koppa (Ϙ). It dropped out of use in favour of sigma in most dialects by the 7th century BC, but was retained in place of the latter in a number of local alphabets until the 5th century BC.[28] It is generally agreed to be derived from Phoenician tsade.

The hypothetical identification between san and sampi is based on a number of considerations. One is the similarity of the sounds represented by both. San represented either simple [s] or some other, divergent phonetic realization of the common Greek /s/ phoneme. Suggestions for its original sound value have included [ts],[4] [z],[28] and [ʃ].[29] The second reason for the assumption is the systematicity in the development of the letter inventory: there were three archaic letters that dropped out of use in alphabetic writing (digamma/wau, koppa, and san), and three extra-alphabetic letters were adopted for the Milesian numeral system, two of them obviously identical with the archaic digamma and koppa; hence, it is easy to assume that the third in the set had the same history. Objections to this account have been related to the fact that sampi did not assume the same position san had had, and to the lack of any obvious relation between the shapes of the two letters and the lack of any intermediate forms linking the two uses.

Among older authorities, Gardthausen[30] and Thompson[31] took the identity between san and sampi for granted. Foat, in a skeptical reassessment of the evidence, came to the conclusion that it was a plausible hypothesis but unprovable.[6][9] The discussion has continued until the present, while a steady trickle of new archaeological discoveries regarding the relative dating of the various events involved (i.e. the original emergence of the alphabet, the loss of archaic san, the emergence of alphabetic sampi, and the emergence of the numeral system) have continued to affect the data base on which it is founded.

A part of the discussion about the identity of san and sampi has revolved around a difficult and probably corrupted piece of philological commentary by an anonymous scholiast, which has been debated ever since Joseph Justus Scaliger drew attention to it in the mid-17th century. Scaliger's discussion also contains the first known attestation of the name "san pi" (sampi) in the western literature, and the first attempt at explaining it. The passage in question is a scholion on two rare words occurring in the comedies of Aristophanes, koppatias (κοππατίας) and samphoras (σαμφόρας). Both were names for certain breeds of horses, and both were evidently named after the letter used as a branding mark on each: "koppa" and "san" respectively. After explaining this, the anonymous scholiast adds a digression that appears to be meant to further explain the name and function of "san", drawing some kind of link between it and the numeral sign of 900. However, what exactly was meant here is obscure now, because the text was evidently corrupted during transmission and the actual symbols cited in it were probably exchanged. The following is the passage in the reading provided by a modern edition, with problematic words marked:

κοππατίας ἵππους ἐκάλουν οἷς ἐγκεχάρακτο τὸ κ[?] στοιχεῖον, ὡς σαμφόρας τοὺς ἐγκεχαραγμένους τὸ σ. τὸ γὰρ σ[?] κατὰ[?] τὸ ϻ[?] χαρασσόμενον ϻὰν[?] ἔλεγον. αἱ δὲ χαράξεις αὗται καὶ μέχρι τοῦ νῦν σῴζονται ἐπὶ τοῖς ἵπποις. συνεζευγμένου δὲ τοῦ κ[?] καὶ σ[?] τὸ σχῆμα τοῦ ἐνακόσιοι[?] ἀριθμοῦ δύναται νοεῖσθαι, οὗ προηγεῖται τὸ κόππα[?]· καὶ παρὰ γραμματικοῖς οὕτω διδάσκεται, καὶ καλεῖται κόππα ἐνενήκοντα.[32]

"Koppatias" were called horses that were branded with the letter κ[?], just as "Samphoras" were those branded with σ[?]. For the "σ"[?] written like [or: together with?] ϻ[?] was called san[?]. These brandings can still be found on horses today. And from a "κ"[?] joined together with "σ"[?], one can see how the number sign for 900[?] is derived, which is preceded by koppa[?]. This is also taught by the grammarians, and the "90" is called "koppa".

There is no agreement on what was originally meant by this passage.[26] While Scaliger in the 17th century believed that the scholiast spoke of san as a synonym for sigma, and meant to describe the (modern) shape of sampi (ϡ) as being composed of an inverted lunate sigma and a π, the modern editor D. Holwerda believes the scholiast spoke of the actual M-shaped san and expressed a belief that modern sampi was related to it.

An alternative hypothesis to that of the historical identity between san and sampi is that Ionian sampi may have been a loan from the neighbouring Anatolian language Carian, which formed the local substrate in the Ionian colonies of Asia Minor. This hypothesis is mentioned by Jeffery[1] and has been supported more recently by Genzardi[33]

Brixhe[34] suggested that sampi could be related to the Carian letter 25 "![]() ", transcribed as ś. This would fit in with the "plausible, but not provable" hypothesis that the root contained in the Carian-Greek names spelled with sampi, "Πανυασσις" and "Οασσασσις", is identical with a root *uś-/waś- identified elsewhere in Carian, which contains the Carian ś sound spelled with

", transcribed as ś. This would fit in with the "plausible, but not provable" hypothesis that the root contained in the Carian-Greek names spelled with sampi, "Πανυασσις" and "Οασσασσις", is identical with a root *uś-/waś- identified elsewhere in Carian, which contains the Carian ś sound spelled with ![]() .[35] Adiego follows this with the hypothesis that both the Carian letter and sampi could ultimately go back to Greek Ζ (

.[35] Adiego follows this with the hypothesis that both the Carian letter and sampi could ultimately go back to Greek Ζ (![]() ). Like the san–sampi hypothesis, the Carian hypothesis remains an open and controversial issue, especially since the knowledge of Carian itself is still fragmentary and developing.[2]

). Like the san–sampi hypothesis, the Carian hypothesis remains an open and controversial issue, especially since the knowledge of Carian itself is still fragmentary and developing.[2]

While the origin of sampi continues to be debated, the identity between the alphabetic Ionian sampi (/ss/) and the numeral for 900 has rarely been in doubt, although in the older literature it was sometimes mentioned only tentatively,[31] An isolated position was expressed in the early 20th century by Jannaris, who – without mentioning the alphabetic use of Ionian /ss/ – proposed that the shape of numeric sampi was derived from a juxtaposition of three "T"s, i.e. 3×300=900. (He also rejected the historical identity of the other two numerals, stigma (6) and koppa (90), with their apparent alphabetic predecessors.)[36] Today, the link between alphabetic and numeral sampi is universally accepted.

Names

[edit]Despite all uncertainties, authors who subscribe to the hypothesis of a historical link between ancient san and sampi also often continue to use the name san for the latter. Benedict Einarson hypothesizes that it was in fact called *ssan, with the special quality of the sibilant sound it had as Ionian ![]() . This opinion has been rejected as phonologically impossible by Soldati,[26] who points out that the /ss/ sound only ever occurred in the middle of words and therefore could not have been used in the beginning of its own name.

. This opinion has been rejected as phonologically impossible by Soldati,[26] who points out that the /ss/ sound only ever occurred in the middle of words and therefore could not have been used in the beginning of its own name.

As for the name sampi itself, it is generally agreed today that it is of late origin and not the original name of the character in either its ancient alphabetic or its numeral function. Babiniotis describes it as "medieval",[37] while Jannaris places its emergence "after the thirteenth century".[36] However, the precise time of its emergence in Greek is not documented.

The name is already attested in manuscript copies of an Old Church Slavonic text describing the development of the alphabet, the treatise On Letters ascribed to the 9th-century monk Hrabar, which was written first in Glagolitic and later transmitted in the Cyrillic script. In one medieval Cyrillic group of manuscripts of this text, probably going back to a marginal note in an earlier Glagolitic version,[38] the letter names "sampi" ("сѧпи") and "koppa" ("копа") are used for the Greek numerals.[39] Witnesses of this textual variant exist from c.1200, but its archetype can be dated to before 1000 AD.[40]

The first reference to the name sampi in the western literature occurs in a 17th-century work, Scaliger's discussion of the Aristophanes scholion regarding the word samphoras (see above). Some modern authors, taking Scaliger's reference as the first known use and unaware of earlier attestations, have claimed that the name itself only originated in the 17th century[41] and/or that Scaliger himself invented it.[42] A related term was used shortly after Scaliger by the French author Montfaucon, who called the sign "ἀντίσιγμα πῖ" (antisigma-pi), "because the Greeks regarded it as being composed of an inverted sigma, which is called ἀντίσιγμα, and from πῖ" ("Graeci putarunt ex inverso sigma, quod ἀντίσιγμα vocatur, et ex πῖ compositum esse").[43]

The etymology of sampi has given rise to much speculation. The only element all authors agree on is that the -pi refers to the letter π, but about the rest accounts differ depending on each author's stance on the question of the historical identity between sampi and san.

According to the original suggestion by Scaliger, san-pi means "written like a san and a pi together". Here, "san" refers not to the archaic letter san (i.e. Ϻ) itself, but to "san" as a mere synonym of "sigma", referring to the outer curve of the modern ϡ as resembling an inverted lunate sigma.[44] This reading is problematic because it fits the shape only of the modern (late Byzantine) sampi but presupposes active use of an archaic nomenclature that had long since lost currency by the time that shape emerged. According to a second hypothesis, san-pi would originally have meant "the san that stands next to pi in the alphabet". This proposal thus presupposes the historical identity between sampi and ancient san (Ϻ), which indeed stood behind Π. However, this account too is problematic as it implies a very early date of the emergence of the name, since after the archaic period the original position of san was apparently no longer remembered, and the whole point of the use of sampi in the numeral system is that it stands somewhere else. Yet a different hypothesis interprets san-pi in the sense of "the san that resembles pi". This is usually taken as referring to the modern ϡ shape, presupposing that the name san alone had persisted from antiquity until the time the sign took that modern shape.[45] None of these hypotheses has wide support today. The most commonly accepted explanation of the name today is that san pi (σὰν πῖ) simply means "like a pi", where the word san is unrelated to any letter name but simply the modern Greek preposition σαν ("like", from ancient Greek ὡς ἂν).[36][37]

In the absence of a proper name, there are indications that various generic terms were used in Byzantine times to refer to the sign. Thus, the 15th-century Greek mathematician Nikolaos Rabdas referred to the three numerals for 6, 90 and 900 as "τὸ ἐπίσημον", "τὸ ἀνώνυμον σημεῖον" ("the nameless sign", i.e. koppa), and "ὁ καλούμενος χαρακτήρ" ("the so-called charaktir", i.e. just "the character"), respectively.[42] The term "ἐπίσημον" (episēmon, literally "outstanding") is today used properly as a generic cover term for all three extra-alphabetic numeral signs, but was used specifically to refer to 6 (i.e. digamma/stigma).

In some early medieval Latin documents from western Europe, there are descriptions of the contemporary Greek numeral system which imply that sampi was known simply by the Greek word for its numeric value, ἐννεακόσια (enneakosia, "nine hundred"). Thus, in De loquela per gestum digitorum, a didactic text about arithmetics attributed to the Venerable Bede, the three Greek numerals for 6, 90 and 900 are called "episimon", "cophe" and "enneacosis" respectively.[46] the latter two being evidently corrupted versions of koppa and enneakosia. An anonymous 9th-century manuscript from Rheinau Abbey[47] has epistmon [sic], kophe, and ennakose.[48] Similarly, the Psalterium Cusanum, a 9th or 10th century bilingual Greek—Latin manuscript, has episimôn, enacôse and cophê respectively (with the latter two names mistakenly interchanged for each other.)[49] Another medieval manuscript has the same words distorted somewhat more, as psima, coppo and enacos,[50] Other, similar versions of the name include enacosin and niacusin,[51][52] or the curious corruption sincope,[53]

A curious name for sampi that occurs in one Greek source is "παρακύϊσμα" (parakyisma). It occurs in a scholion to Dionysius Thrax,[54] where the three numerals are referred to as "τὸ δίγαμμα καὶ τὸ κόππα καὶ τό καλούμενον παρακύϊσμα". The obscure word ("… the so-called parakyisma") literally means "a spurious pregnancy", from "παρα-" and the verb "κυέω" "to be pregnant". The term has been used and accepted as possibly authentic by Jannaris,[36] Uhlhorn[55] and again by Soldati.[26] While Jannaris hypothesizes that it was meant to evoke the oblique, reclining shape of the character, Soldati suggests it was meant to evoke its status as an irregular, out-of-place addition ("un'utile superfetazione"). Einarson, however, argues that the word is probably the product of textual corruption during transmission in the Byzantine period.[42] He suggests that the original reading was similar to that used by Rabdas, "ὁ καλούμενος χαρακτήρ" ("the so-called character"). Another contemporary cover term for the extra-alphabetic numerals would have been "παράσημον" (parasēmon, lit. "extra sign"). A redactor could have written the consonant letters "π-σ-μ" of "παράσημον" over the letters "χ-κτ-ρ" of "χαρακτήρ", as both words happen to share their remaining intermediate letters. The result, mixed together from letters of both words, could have been misread in the next step as "παρακυησμ", and hence, "παρακύϊσμα".

An entirely new proposal has been made by A. Willi, who suggests that the original name of the letter in ancient Greek was angma (ἄγμα).[3] This proposal is based on a passage in a Latin grammarian, Varro, who uses this name for what he calls a "25th letter" of the alphabet. Varro himself is clearly not referring to sampi, but is using angma to refer to the ng sound [ŋ] in words like angelus. However, Varro ascribes the use of the name angma to an ancient Ionian Greek author, Ion of Chios. Willi conjectures that Varro misunderstood Ion, believing the name angma referred to the [ŋ] sound because that sound happened to occur in the name itself. However, Ion, in speaking of a "25th letter of the alphabet", meant not just a different pronunciation of some other letters but an actual written letter in its own right, namely sampi. According to Willi's hypothesis, the name angma would have been derived from the verbal root *ank-, "to bend, curve", and referred to a "crooked object", used because of the hook-like shape of the letter.

In other scripts

[edit]

In the Greco–Iberian alphabet, used during the 4th century BC in eastern Spain to write the Iberian language (a language unrelated to Greek), sampi was adopted along with the rest of the Ionian Greek alphabet, as an alphabetic character to write a second sibilant sound distinct from sigma. It had the shape ![]() , with three vertical lines of equal length.[56]

Its pronunciation is uncertain, but it is transliterated as ⟨s⟩.

, with three vertical lines of equal length.[56]

Its pronunciation is uncertain, but it is transliterated as ⟨s⟩.

The Greek script was also adapted in Hellenistic times to write the Iranian language Bactrian, spoken in today's Afghanistan. Bactrian used an additional letter "sho"(Ϸ), shaped like the later (unrelated) Germanic letter "thorn" (Þ), to denote its sh sound (š, [ʃ]). This letter, too, has been hypothesized to be a continuation of Greek sampi, and/or san.[29][57]

During the first millennium AD, several neighboring languages whose alphabets were wholly or partly derived from the Greek adopted the structure of the Greek numeral system, and with it, some version or local replacement of sampi.

In Coptic, the sign "Ⳁ" (![]() , which has been described as "the Greek

, which has been described as "the Greek ![]() with a Ρ above"[55]), was used for 900.[58][59] Its numeric role was subsequently taken over by the native character Ϣ (shei, /ʃ/), which is related to the Semitic tsade (and thus, ultimately, cognate with Greek san as well).[60]

with a Ρ above"[55]), was used for 900.[58][59] Its numeric role was subsequently taken over by the native character Ϣ (shei, /ʃ/), which is related to the Semitic tsade (and thus, ultimately, cognate with Greek san as well).[60]

The Gothic alphabet adopted sampi in its Roman-era form of an upwards-pointing arrow (![]() , 𐍊)[61]

, 𐍊)[61]

In the Slavic writing system Glagolitic, the letter ![]() (tse, /ts/) was used for 900. It too may have been derived from a form of the Hebrew tsade.[62] In Cyrillic, in contrast, the character Ѧ (small yus, /ẽ/) was used initially, being the one among the native Cyrillic letters that resembled sampi most closely in shape. However, the letter Ц (tse), the equivalent of the Glagolitic sign, took its place soon later. It has been proposed that sampi was retained in its alternative function of denoting multiplication by thousand, and became the Cyrillic "thousands sign" ҂.[38]

(tse, /ts/) was used for 900. It too may have been derived from a form of the Hebrew tsade.[62] In Cyrillic, in contrast, the character Ѧ (small yus, /ẽ/) was used initially, being the one among the native Cyrillic letters that resembled sampi most closely in shape. However, the letter Ц (tse), the equivalent of the Glagolitic sign, took its place soon later. It has been proposed that sampi was retained in its alternative function of denoting multiplication by thousand, and became the Cyrillic "thousands sign" ҂.[38]

In Armenian, the letter Ջ (ǰ) stands for 900, while Ք (kʿ), similar in shape to the Coptic sign, stands for 9000.

Modern use

[edit]Together with the other elements of the Greek numeral system, sampi is occasionally still used in Greek today. However, since the system is typically used only to enumerate items in relatively small sets, such as the chapters of a book or the names of rulers in a dynasty, the signs for the higher tens and hundreds, including sampi, are much less frequently found in practice than the lower letters for 1 to 10. One of the few domains where higher numbers including thousands and hundreds are still expressed in the old system in Greece with some regularity is the field of law, because until 1914 laws were numbered in this way. For instance, one law which happens to have sampi in its name and is still in force and relatively often referred to is "Νόμος ͵ΓϠΝʹ/1911" (i.e. Law Number 3950 of 1911), "Περί της εκ των αυτοκινήτων ποινικής και αστικής ευθύνης" ("About penal and civil responsibility arising from the use of automobiles").[63] However, in informal practice, the letter sampi is often replaced in such instances by a lowercase or uppercase π.

Typography

[edit]

With the advent of modern printing in the western Renaissance, printers adopted the minuscule version of the numeral sign, ϡ, for their fonts. The typographic realization of Sampi has varied widely throughout its history in print, and a large range of different shapes can still be found in current electronic typesetting. Commonly used forms range from small, π-like shapes (![]() ) to shapes with large swash curves (

) to shapes with large swash curves (![]() ), while the stems can be almost upright (

), while the stems can be almost upright (![]() ) or almost horizontal (

) or almost horizontal (![]() ). More rarely, one can find shapes with the lower end curving outwards, forming an "s" curve (

). More rarely, one can find shapes with the lower end curving outwards, forming an "s" curve (![]() ).

).

In its modern use as a numeral (as with the other two episema, stigma and koppa) no difference is normally made in print between an upper case and lower case form;[64] the same character is typically used in both environments. However, occasionally special typographic variants adapted to an upper case style have also been employed in print. The issue of designing such uppercase variants has become more prominent since the decision of Unicode to encode separate character codepoints for uppercase and lowercase sampi.[65][66] Several different designs are currently found. Older versions of the Unicode charts showed a glyph with a crooked and thicker lower stem (![]() ).[67] While this form has been adopted in some modern fonts, it has been replaced in more recent versions of Unicode with a simpler glyph, similar to the lowercase forms (

).[67] While this form has been adopted in some modern fonts, it has been replaced in more recent versions of Unicode with a simpler glyph, similar to the lowercase forms (![]() ).[68] Many fonts designed for scholarly use have adopted an upright triangular shape with straight lines and serifs (

).[68] Many fonts designed for scholarly use have adopted an upright triangular shape with straight lines and serifs (![]() ), as proposed by the typographer Yannis Haralambous.[66] Other versions include large curved shapes (

), as proposed by the typographer Yannis Haralambous.[66] Other versions include large curved shapes (![]() ), or an upright large π-like glyph with a long descending curve (

), or an upright large π-like glyph with a long descending curve (![]() ).

).

The epigraphic ancient Ionian sampi is not normally rendered with the modern numeral character in print. In specialized epigraphical or palaeographic academic discussion, it is either represented by a glyph ![]() , or by a Latin capital serifed T as a makeshift replacement. As this character has in the past never been supported in normal Greek fonts, there is no typographical tradition for its uppercase and lowercase representation in the style of a normal text font. Since its inclusion in the Unicode character encoding standard, experimental typographical stylizations of a lowercase textual Sampi have been developed. The Unicode reference glyph for "small letter archaic sampi", according to an original draft, was to have looked like the stem of a small τ with a square top at x height,[69] but was changed after consultation with Greek typesetting experts.[70] The glyph shown in current official code charts stands on the baseline and has an ascender slightly higher than cap height, but its stem has no serifs and is slightly curved leftwards like the descender of an ρ or β. Most type designers who have implemented the character in current fonts have chosen to design a glyph either at x height, or with a descender but no ascender, and with the top either square or curved (corresponding to ancient scribal practice.[26])

, or by a Latin capital serifed T as a makeshift replacement. As this character has in the past never been supported in normal Greek fonts, there is no typographical tradition for its uppercase and lowercase representation in the style of a normal text font. Since its inclusion in the Unicode character encoding standard, experimental typographical stylizations of a lowercase textual Sampi have been developed. The Unicode reference glyph for "small letter archaic sampi", according to an original draft, was to have looked like the stem of a small τ with a square top at x height,[69] but was changed after consultation with Greek typesetting experts.[70] The glyph shown in current official code charts stands on the baseline and has an ascender slightly higher than cap height, but its stem has no serifs and is slightly curved leftwards like the descender of an ρ or β. Most type designers who have implemented the character in current fonts have chosen to design a glyph either at x height, or with a descender but no ascender, and with the top either square or curved (corresponding to ancient scribal practice.[26])

Computer encoding

[edit]

Several codepoints for the encoding of sampi and its variants have been included in Unicode. As they were adopted successively in different versions of Unicode, their coverage in current computer fonts and operating systems is inconsistent as of 2010. U+03E0 ("Greek letter Sampi") was present from version 1.1 (1993) and was originally meant to show the normal modern numeral glyph. The uppercase/lowercase contrast was introduced with version 3.0 (1999).[65][71] As the existing code point had been technically defined as an uppercase character, the new addition was declared lowercase (U+03E1, "Greek small letter Sampi"). This has led to some inconsistency between fonts,[72] because the glyph that was present at U+03E0 in older fonts is now usually found at U+03E1 in newer ones, while U+03E0 may have a typographically uncommon capital glyph.

New, separate codepoints for ancient epigraphic sampi, also in an uppercase and lowercase variant, were proposed in 2005,[73] and included in the standard with version 5.1 (2008).[71] They are meant to cover both the Ionian ![]() and Pamphylian

and Pamphylian ![]() , with the Ionian character serving as the reference glyph. As of 2010, these characters are not yet supported by most current Greek fonts.[74] The Gothic "900" symbol was encoded in version 3.1 (2001), and Coptic sampi in version 4.1 (2005). Codepoints for the related Greek characters san and Bactrian "sho" were added in version 4.0 (2003).

, with the Ionian character serving as the reference glyph. As of 2010, these characters are not yet supported by most current Greek fonts.[74] The Gothic "900" symbol was encoded in version 3.1 (2001), and Coptic sampi in version 4.1 (2005). Codepoints for the related Greek characters san and Bactrian "sho" were added in version 4.0 (2003).

Prior to Unicode, support for sampi in electronic encoding was marginal. No common 8-bit codepage for Greek (such as ISO 8859-7) contained sampi. However, lowercase and uppercase sampi were provided for by the ISO 5428:1984 Greek alphabet coded character set for bibliographic information interchange.[65] In Beta code, lowercase and uppercase sampi are encoded as "#5" and "*#5" respectively.[75] In the LaTeX typesetting system, the "Babel" package allows accessing lowercase and uppercase sampi through the commands "\sampi" and "\Sampi".[76] Non-Unicode (8-bit) fonts for polytonic Greek sometimes contained sampi mapped to arbitrary positions, but usually not as a casing pair. For instance, the "WP Greek Century" font that came with WordPerfect had sampi encoded as 0xFC, while the popular "Wingreek" fonts had it encoded as 0x22. No encoding system prior to Unicode 5.1 catered for archaic epigraphic sampi separately.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Jeffery, Lilian H. (1961). The local scripts of archaic Greece. Oxford: Clarendon. pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c d Wachter, R. (1998). "Eine Weihung an Athena von Assesos". Epigraphica Anatolica. 30: 1–8.

- ^ a b c Willi, Andreas (2008). "Cows, houses, hooks: the Graeco-Semitic letter names as a chapter in the history of the alphabet". Classical Quarterly. 58 (2): 401–423, here: p.419f. doi:10.1017/S0009838808000517. S2CID 170573480.

- ^ a b Woodard, Roger D. (1997). Greek writing from Knossos to Homer: a linguistic interpretation of the origin of the Greek alphabet and the continuity of ancient Greek literacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 177–179. ISBN 978-0-19-510520-9.

- ^ C. Brixhe, "History of the Alpbabet", in Christidēs, Arapopoulou, & Chritē, eds., 2007, A History of Ancient Greek

- ^ a b c Foat, F. W. G. (1906). "Fresh evidence for Ͳ[Sampi]". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 26: 286–287. doi:10.2307/624383. JSTOR 624383. S2CID 164111611.

- ^ "Poinikastas, Ephesos number 1335".

- ^ British Museum No. 886, "PHI Greek Inscriptions – Halikarnassos 1".

- ^ a b Foat, F. W. G. (1905). "Tsade and Sampi". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 25: 338–365. doi:10.2307/624245. JSTOR 624245. S2CID 163644187.

- ^ Herrmann, Peter; Feissel, Denis (2006). Inschriften von Milet: Milet. Inschriften n. 1020 - 1580. Vol. 3/6. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 173–174. ISBN 9783110189667.

- ^ Boegehold, Alan L. (1962). "The Nessos Amphora: a Note on the Inscription". American Journal of Archaeology. 66 (4): 405–406. doi:10.2307/502029. JSTOR 502029. S2CID 191375914.

- ^ a b Threatte, Leslie (1980). The grammar of Attic inscriptions: phonology. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 24.

- ^ Brixhe, Claude (1976). Le Dialecte grec de Pamphylie: Documents et grammaire. Paris. pp. 7–9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "PHI Greek Inscriptions – IK Perge 1".. Other editions read "Klevutas" and "Lwaravu". "Ͷ" (transliterated "V") here stands for a second nonstandard letter, "Pamphylian digamma".

- ^ "PHI Greek Inscriptions – Brixhe, Dial.gr.Pamph.1".

- ^ Thompson, Handbook, p. 114.

- ^ "PHI Greek Inscriptions – IG I³ 1387"., also known as IG I² 760.

- ^ Schärlig, Alain (2001). Compter avec des cailloux: le calcul élémentair sur l'abaque chez les anciens Grecs. Lausanne: Presses polytechniques et universitaires Romandes. p. 95.

- ^ "PHI Greek Inscriptions – Magnesia 4"., also known as Syll³ 695.b.

- ^ "PHI Greek Insriptions – IG II² 2776".

- ^ a b c Tod, Marcus N. (1950). "The alphabetic numeral system in Attica". Annual of the British School at Athens. 45: 126–139. doi:10.1017/s0068245400006730. S2CID 128438705.

- ^ Boegehold, Alan L. (1960). "Aristotle's Athenaion Politeia 65,2: the 'official token'". Hesperia. 29 (4): 393–401. doi:10.2307/147161. JSTOR 147161.

- ^ Gardthausen, Viktor (1913). Griechische Palaeographie. Vol. 2: Die Schrift, Unterschriften und Chronologie im Altertum und im byzantinischen Mittelalter. Leipzig: Veit. pp. 368–370.

- ^ Galen (1821–1823). Galenis opera omnia, Vol. 17a. Leipzig: Car. Cnobloch. p. 525.

- ^ Foat, F. W. G. (1902). "Sematography of the Greek papyri". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 22: 135–173. doi:10.2307/623924. JSTOR 623924. S2CID 163867567.

- ^ a b c d e f Soldati, Agostino (2006). ""Τὸ καλούμενον παρακύϊσμα": Le forme del sampi nei papiri". Archiv für Papyrusforschung und Verwandte Gebiete. 52 (2): 209–217. doi:10.1515/apf.2006.52.2.209. S2CID 179007763.

- ^ Gardthausen, Palaeographie, p.167.

- ^ a b Jeffery, Local Scripts, p. 33.

- ^ a b Tarn, William Woodthorpe (1961). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 508. ISBN 9781108009416.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Gardthausen, Griechische Palaeographie, p.369.

- ^ a b Thompson, Handbook, p.7.

- ^ Holwerda, D. (1977). Prolegomena de comoedia. Scholia in Acharnenses, Equites, Nubes (Scholia in Aristophanem 1.3.1.). Groningen: Bouma. p. 13.

- ^ Genzardi, Giuseppe (1987). "Una singolare lettera greca: il Sampi". Rendiconti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. 42: 303–309.

- ^ Brixhe, Claude (1982). "Palatalisations en grec et en phrygien". Bulletin de la Société linguistique de Paris. 77: 209–249.

- ^ Adiego, Ignacio-J. (1998). "Die neue Bilingue von Kaunos und das Problem des karischen Alphabets". Kadmos. 37 (1–2): 57–79. doi:10.1515/kadm.1998.37.1-2.57. S2CID 162337167.

- ^ a b c d Jannaris, A. N. (1907). "The Digamma, Koppa, and Sampi as numerals in Greek". The Classical Quarterly. 1: 37–40. doi:10.1017/S0009838800004936. S2CID 171007977.

- ^ a b Babiniotis, Georgios. "σαμπί". Lexiko tis Neas Ellinikis Glossas.

- ^ a b Veder, William R. (1999). Utrum in alterum abiturum erat?: a study of the beginnings of text transmission in Church Slavic. Bloomington: Slavica. p. 177.

- ^ Veder, Utrum in alterum, p.133f.

- ^ Veder, Utrum in alterum, p.184.

- ^ Thus Keil, Halikarnassische Inschrift, p.265; also Foat, Tsade and Sampi, p.344, and Willi, Cows, houses, hooks, p.420.

- ^ a b c Einarson, Benedict (1967). "Notes on the development of the Greek alphabet". Classical Philology. 62: 1–24, especially p.13 and 22. doi:10.1086/365183. S2CID 161310875.

- ^ Montfaucon, Bernard de (1708). Palaeographia Graeca. Paris: Guerin, Boudot & Robustel. p. 132.; cited in Soldati, Τὸ λεγόμενο παρακύϊσμα, p. 210.

- ^ Scaliger, Joseph (1658). Animadversiones in chronologia Eusebii. Amsterdam: Janssonius. pp. 115–116.

- ^ Thompson, Handbook, p. 104.

- ^ Beda [Venerabilis]. "De loquela per gestum digitorum". In Migne, J.P. (ed.). Opera omnia, vol. 1. Paris. p. 697.

- ^ Zürich, Central Library, Codex Rh.131. The same manuscript is referred to as "Alphabet von Sankt Gallen" by Victor Gardthausen, Griechische Palaeographie, p. 368.

- ^ von Wyss, Paul Friedrich (1850). Alamannische Formeln und Briefe aus dem Neunten Jahrhundert. Zürich. p. 31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gardthausen, Griechische Palaeographie, p.260.

- ^ The Bodleian quarterly record 3 (1923), p.96

- ^ Lauth, Franz Joseph (1857). Das germanische Runen-Fudark, aus den Quellen kritisch erschlossen. München: Lauth. p. 17.

Niacusin.

- ^ Atto [of Vercelli] (1884). Migne, J. P. (ed.). Attonis Vercellensis opera omnia. Paris: Garnier. p. 13.

- ^ Hofman, Rijcklof (1996). The Sankt Gall Priscan Commentary, Part 1, Vol 2. Münster: Nodus. p. 32.

- ^ Hilgard, Alfred (ed.). Scholia Londinensia in Dionyisii Thracis Artem grammaticem (Grammatici Graeci, Vol. I:3. Leipzig. p. 429.

- ^ a b Uhlhorn, F. (1925). "Die Großbuchstaben der sogenannten gotischen Schrift". Zeitschrift für Buchkunde. 2: 57–64 and 64–74.

- ^ Hoz, Javier de (1998). "Epigrafía griega de occidente y escritura greco-ibérica". In Cabrera Bonet, P.; Sánchez Fernández, C. (eds.). Los griegos en España: tras las huellas de Heracles. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Cultura. pp. 180–196.

- ^ Sheldon, John (2003). "Iranian Evidence for Pindar's Spurious San?". Antichthon. 37: 52–61. doi:10.1017/S0066477400001416. S2CID 141879381.

- ^ Layton, Bentley (2000). A Coptic grammar, with chrestomathy and glossary. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz. p. 59. ISBN 9783447042406.

- ^ "Revised proposal to add the Coptic alphabet to the BMP of the UCS (N2636)" (PDF). 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-12-11. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- ^ Foat, Tsade and Sampi, p.363, refers to Ϣ as itself a version of sampi.

- ^ Braune, Wilhelm (1895). A Gothic Grammar - With Selections for Reading and a Glossary. London: Kegan Paul. p. 2.

- ^ Schenker, Alexander M. (1995). "Early Writing". The dawn of Slavic: an introduction to Slavic philology. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 168–172. ISBN 0-300-05846-2.

- ^ Küster, Marc Wilhelm (2006). Geordnetes Weltbild: die Tradition des alphabetischen Sortierens von der Keilschrift bis zur EDV. Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 225, 653.

- ^ Holton, David; Mackridge, Peter; Philippaki-Warburton, Irene (1997). Greek: a comprehensive grammar of the modern language. London: Routledge. p. 105.

- ^ a b c Everson, Michael (1998). "Additional Greek characters for the UCS" (PDF).

- ^ a b Haralambous, Yannis (1999). "From Unicode to typography, a case study: the Greek script" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-04.

- ^ "The Unicode Standard 3.1. Greek and Coptic" (PDF).

- ^ "The Unicode Standard 5.2. Greek and Coptic" (PDF).

- ^ "Summary of repertoire for second PDAM 3 of ISO/IEC 10646" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-04. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ^ "ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N 3891" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ^ a b Unicode Consortium. "Unicode Character Database: Derived Property Data". Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- ^ Nicholas, Nick. "Numerals". Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- ^ Nicholas, Nick (2005). "Proposal to add Greek epigraphical letters to the UCS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2006. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- ^ The following free fonts have implemented the new characters: "IFAO-Grec Unicode" (Institut français d'archéologie orientale. "Polices de caractères". Retrieved 2010-10-03.), "New Athena Unicode" (Donald Mastronarde. "About New Athena Unicode Font".), and a group of fonts including "Alfios", "Aroania", "Atavyros" and others (George Douros. "Unicode fonts for ancient scripts". Retrieved 2010-10-03.).

- ^ "The TLG Beta Code Manual 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-10-04.

- ^ Beccari, Claudio (2010). "Teubner.sty: An extension to the greek option of the babel package" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-10-04.

Sources

[edit]- Thompson, Edward M. (1893). Handbook of Greek and Latin palaeography. New York: D. Appleton. p. 7.