Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Hand | |

|---|---|

Back of a human's left hand | |

Front of a human's left hand | |

| Details | |

| Vein | Dorsal venous network of hand |

| Nerve | Ulnar, median, radial nerves |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | manus |

| MeSH | D006225 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.025 |

| TA2 | 148 |

| FMA | 9712 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

A hand is a prehensile, multi-fingered appendage located at the end of the forearm or forelimb of primates such as humans, chimpanzees, monkeys, and lemurs. A few other vertebrates such as the koala (which has two opposable thumbs on each "hand" and fingerprints extremely similar to human fingerprints) are often described as having "hands" instead of paws on their front limbs. The raccoon is usually described as having "hands" though opposable thumbs are lacking.[1]

Some evolutionary anatomists use the term hand to refer to the appendage of digits on the forelimb more generally—for example, in the context of whether the three digits of the bird hand involved the same homologous loss of two digits as in the dinosaur hand.[2]

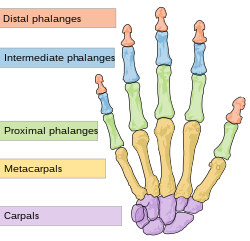

The human hand usually has five digits: four fingers plus one thumb;[3][4] however, these are often referred to collectively as five fingers, whereby the thumb is included as one of the fingers.[3][5][6] It has 27 bones, not including the sesamoid bone, the number of which varies among people,[7] 14 of which are the phalanges (proximal, intermediate and distal) of the fingers and thumb. The metacarpal bones connect the fingers and the carpal bones of the wrist. Each human hand has five metacarpals[8] and eight carpal bones.

Fingers contain some of the densest areas of nerve endings in the body, and are the richest source of tactile feedback. They also have the greatest positioning capability of the body; thus, the sense of touch is intimately associated with hands. Like other paired organs (eyes, feet, legs) each hand is dominantly controlled by the opposing brain hemisphere, so that handedness—the preferred hand choice for single-handed activities such as writing with a pencil—reflects individual brain functioning.

Among humans, the hands play an important function in body language and sign language. Likewise, the ten digits of two hands and the twelve phalanges of four fingers (touchable by the thumb) have given rise to number systems and calculation techniques.

Structure

[edit]Many mammals and other animals have grasping appendages similar in form to a hand such as paws, claws, and talons, but these are not scientifically considered to be grasping hands. The scientific use of the term hand in this sense to distinguish the terminations of the front paws from the hind ones is an example of anthropomorphism. The only true grasping hands appear in the mammalian order of primates. Hands must also have opposable thumbs, as described later in the text.

The hand is located at the distal end of each arm. Apes and monkeys are sometimes described as having four hands, because the toes are long and the hallux is opposable and looks more like a thumb, thus enabling the feet to be used as hands.

The word "hand" is sometimes used by evolutionary anatomists to refer to the appendage of digits on the forelimb such as when researching the homology between the three digits of the bird hand and the dinosaur hand.[2]

An adult human male's hand weighs about a pound.[9]

Areas

[edit]

Areas of the human hand include:

- The palm (volar), which is the central region of the anterior part of the hand, located superficially to the metacarpus. The skin in this area contains dermal papillae to increase friction, such as are also present on the fingers and used for fingerprints.

- The opisthenar area (dorsal) is the corresponding area on the posterior part of the hand.

- The heel of the hand is the area anteriorly to the bases of the metacarpal bones, located in the proximal part of the palm. It is the area that sustains most pressure when using the palm of the hand for support, such as in handstand. Its skeletal foundation is formed by the distal row of carpal bones (specifically the hamate, capitate, trapezoid, and trapezium) and the bases of the metacarpal bones. The skin is thick and tough, adapted for pressure and friction, a layer of subcutaneous fat and connective tissue provides cushioning, and palmar fascia contributes to the palm's shape and stability.

There are five digits attached to the hand, notably with a nail fixed to the end in place of the normal claw. The four fingers can be folded over the palm which allows the grasping of objects. Each finger, starting with the one closest to the thumb, has a colloquial name to distinguish it from the others:

- index finger, pointer finger, forefinger, or 2nd digit

- middle finger or long finger or 3rd digit

- ring finger or 4th digit

- little finger, pinky finger, small finger, baby finger, or 5th digit

The thumb (connected to the first metacarpal bone and trapezium) is located on one of the sides, parallel to the arm. A reliable way of identifying human hands is from the presence of opposable thumbs. Opposable thumbs are identified by the ability to be brought opposite to the fingers, a muscle action known as opposition.

Bones

[edit]

The skeleton of the human hand consists of 27 bones:[10] the eight short carpal bones of the wrist are organized into a proximal row (scaphoid, lunate, triquetral and pisiform) which articulates with the bones of the forearm, and a distal row (trapezium, trapezoid, capitate and hamate), which articulates with the bases of the five metacarpal bones of the hand. The heads of the metacarpals will each in turn articulate with the bases of the proximal phalanx of the fingers and thumb. These articulations with the fingers are the metacarpophalangeal joints known as the knuckles. At the palmar aspect of the first metacarpophalangeal joints are small, almost spherical bones called the sesamoid bones. The fourteen phalanges make up the fingers and thumb, and are numbered I-V (thumb to little finger) when the hand is viewed from an anatomical position (palm up). The four fingers each consist of three phalanx bones: proximal, middle, and distal. The thumb only consists of a proximal and distal phalanx.[11] Together with the phalanges of the fingers and thumb these metacarpal bones form five rays or poly-articulated chains.

Because supination and pronation (rotation about the axis of the forearm) are added to the two axes of movements of the wrist, the ulna and radius are sometimes considered part of the skeleton of the hand.

There are numerous sesamoid bones in the hand, small ossified nodes embedded in tendons; the exact number varies between people:[7] whereas a pair of sesamoid bones are found at virtually all thumb metacarpophalangeal joints, sesamoid bones are also common at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb (72.9%) and at the metacarpophalangeal joints of the little finger (82.5%) and the index finger (48%). In rare cases, sesamoid bones have been found in all the metacarpophalangeal joints and all distal interphalangeal joints except that of the long finger.

The articulations are:

- interphalangeal articulations of hand (the hinge joints between the bones of the digits)

- metacarpophalangeal joints (where the digits meet the palm)

- intercarpal articulations (where the palm meets the wrist)

- wrist (may also be viewed as belonging to the forearm).

Arches

[edit]

Red: one of the oblique arches

Brown: one of the longitudinal arches of the digits

Dark green: transverse carpal arch

Light green: transverse metacarpal arch

The fixed and mobile parts of the hand adapt to various everyday tasks by forming bony arches: longitudinal arches (the rays formed by the finger bones and their associated metacarpal bones), transverse arches (formed by the carpal bones and distal ends of the metacarpal bones), and oblique arches (between the thumb and four fingers):

Of the longitudinal arches or rays of the hand, that of the thumb is the most mobile (and the least longitudinal). While the ray formed by the little finger and its associated metacarpal bone still offers some mobility, the remaining rays are firmly rigid. The phalangeal joints of the index finger, however, offer some independence to its finger, due to the arrangement of its flexor and extension tendons.[12]

The carpal bones form two transversal rows, each forming an arch concave on the palmar side. Because the proximal arch simultaneously has to adapt to the articular surface of the radius and to the distal carpal row, it is by necessity flexible. In contrast, the capitate, the "keystone" of the distal arch, moves together with the metacarpal bones and the distal arch is therefore rigid. The stability of these arches is more dependent of the ligaments and capsules of the wrist than of the interlocking shapes of the carpal bones, and the wrist is therefore more stable in flexion than in extension.[12] The distal carpal arch affects the function of the CMC joints and the hands, but not the function of the wrist or the proximal carpal arch. The ligaments that maintain the distal carpal arches are the transverse carpal ligament and the intercarpal ligaments (also oriented transversally). These ligaments also form the carpal tunnel and contribute to the deep and superficial palmar arches. Several muscle tendons attaching to the TCL and the distal carpals also contribute to maintaining the carpal arch.[13]

Compared to the carpal arches, the arch formed by the distal ends of the metacarpal bones is flexible due to the mobility of the peripheral metacarpals (thumb and little finger). As these two metacarpals approach each other, the palmar gutter deepens. The central-most metacarpal (middle finger) is the most rigid. It and its two neighbors are tied to the carpus by the interlocking shapes of the metacarpal bones. The thumb metacarpal only articulates with the trapezium and is therefore completely independent, while the fifth metacarpal (little finger) is semi-independent with the fourth metacarpal (ring finger) which forms a transitional element to the fifth metacarpal.[12]

Together with the thumb, the four fingers form four oblique arches, of which the arch of the index finger functionally is the most important, especially for precision grip, while the arch of the little finger contribute an important locking mechanism for power grip. The thumb is undoubtedly the "master digit" of the hand, giving value to all the other fingers. Together with the index and middle finger, it forms the dynamic tridactyl configuration responsible for most grips not requiring force. The ring and little fingers are more static, a reserve ready to interact with the palm when great force is needed.[12]

Muscles

[edit]

The muscles acting on the hand can be subdivided into two groups: the extrinsic and intrinsic muscle groups. The extrinsic muscle groups are the long flexors and extensors. They are called extrinsic because the muscle belly is located on the forearm.

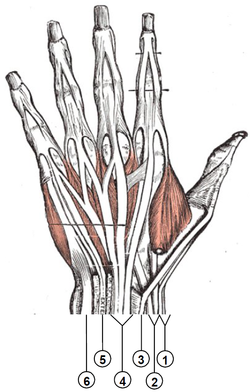

Intrinsic

[edit]The intrinsic muscle groups are the thenar (thumb) and hypothenar (little finger) muscles; the interosseous muscles (four dorsally and three volarly) originating between the metacarpal bones; and the lumbrical muscles arising from the deep flexor (and are special because they have no bony origin) to insert on the dorsal extensor hood mechanism.[14]

Extrinsic

[edit]

The fingers have two long flexors, located on the underside of the forearm. They insert by tendons to the phalanges of the fingers. The deep flexor attaches to the distal phalanx, and the superficial flexor attaches to the middle phalanx. The flexors allow for the actual bending of the fingers. The thumb has one long flexor and a short flexor in the thenar muscle group. The human thumb also has other muscles in the thenar group (opponens and abductor brevis muscle), moving the thumb in opposition, making grasping possible.

The extensors are located on the back of the forearm and are connected in a more complex way than the flexors to the dorsum of the fingers. The tendons unite with the interosseous and lumbrical muscles to form the extensorhood mechanism. The primary function of the extensors is to straighten out the digits. The thumb has two extensors in the forearm; the tendons of these form the anatomical snuff box. Also, the index finger and the little finger have an extra extensor used, for instance, for pointing. The extensors are situated within 6 separate compartments.

| Compartment 1 (Most radial) | Compartment 2 | Compartment 3 | Compartment 4 | Compartment 5 | Compartment 6 (Most ulnar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abductor pollicis longus | Extensor carpi radialis longus | Extensor pollicis longus | Extensor indicis | Extensor digiti minimi | Extensor carpi ulnaris |

| Extensor pollicis brevis | Extensor carpi radialis brevis | Extensor digitorum communis |

The first four compartments are located in the grooves present on the dorsum of inferior side of radius while the 5th compartment is in between radius and ulna. The 6th compartment is in the groove on the dorsum of inferior side of ulna.

Nerve supply

[edit]

The hand is innervated by the radial, median, and ulnar nerves.

- Motor

The radial nerve supplies the finger extensors and the thumb abductor, thus the muscles that extends at the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints (knuckles); and that abducts and extends the thumb. The median nerve supplies the flexors of the wrist and digits, the abductors and opponens of the thumb, the first and second lumbrical. The ulnar nerve supplies the remaining intrinsic muscles of the hand.[15]

All muscles of the hand are innervated by the brachial plexus (C5–T1) and can be classified by innervation:[16]

| Nerve | Muscles |

|---|---|

| Radial | Extensors: carpi radialis longus and brevis, digitorum, digiti minimi, carpi ulnaris, pollicis longus and brevis, and indicis. Other: abductor pollicis longus. |

| Median | Flexors: carpi radialis, pollicis longus, digitorum profundus (half), superficialis, and pollicis brevis (superficial head). Other: palmaris longus. abductor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and first and second lumbricals. |

| Ulnar | Flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum profundus (half), palmaris brevis, flexor digiti minimi, abductor digiti minimi, opponens digiti minimi, adductor pollicis, flexor pollicis brevis (deep head), palmar and dorsal interossei, and third and fourth lumbricals. |

- Sensory

The radial nerve supplies the skin on the back of the hand from the thumb to the ring finger and the dorsal aspects of the index, middle, and half ring fingers as far as the proximal interphalangeal joints. The median nerve supplies the palmar side of the thumb, index, middle, and half ring fingers. Dorsal branches innervates the distal phalanges of the index, middle, and half ring fingers. The ulnar nerve supplies the ulnar third of the hand, both at the palm and the back of the hand, and the little and half ring fingers.[15]

There is a considerable variation to this general pattern, except for the little finger and volar surface of the index finger. For example, in some individuals, the ulnar nerve supplies the entire ring finger and the ulnar side of the middle finger, whilst, in others, the median nerve supplies the entire ring finger.[15]

Blood supply

[edit]

The hand is supplied with blood from two arteries, the ulnar artery and the radial artery. These arteries form three arches over the dorsal and palmar aspects of the hand, the dorsal carpal arch (across the back of the hand), the deep palmar arch, and the superficial palmar arch. Together these three arches and their anastomoses provide oxygenated blood to the palm, the fingers, and the thumb.

The hand is drained by the dorsal venous network of the hand with deoxygenated blood leaving the hand via the cephalic vein and the basilic vein.

Skin

[edit]Right: Sexual dimorphism

The glabrous (hairless) skin on the front of the hand, the palm, is relatively thick and can be bent along the hand's flexure lines where the skin is tightly bound to the underlying tissue and bones. Compared to the rest of the body's skin, the hands' palms (as well as the soles of the feet) are usually lighter—and even much lighter in dark-skinned individuals, compared to the other side of the hand. Indeed, genes specifically expressed in the dermis of palmoplantar skin inhibit melanin production and thus the ability to tan, and promote the thickening of the stratum lucidum and stratum corneum layers of the epidermis. All parts of the skin involved in grasping are covered by papillary ridges (fingerprints) acting as friction pads. In contrast, the hairy skin on the dorsal side is thin, soft, and pliable, so that the skin can recoil when the fingers are stretched. On the dorsal side, the skin can be moved across the hand up to 3 cm (1.2 in); an important input the cutaneous mechanoreceptors.[17]

The web of the hand is a "fold of skin which connects the digits".[18] These webs, located between each set of digits, are known as skin folds (interdigital folds or plica interdigitalis). They are defined as "one of the folds of skin, or rudimentary web, between the fingers and toes".[19]

Variation

[edit]The ratio of the length of the index finger to the length of the ring finger in adults is affected by the level of exposure to male sex hormones of the embryo in utero. This digit ratio is below 1 for both sexes but it is lower in males than in females on average.

Functions

[edit]In primates, hands are not only used for locomotion, but can be used for hand movements like grasping and gripping onto objects. In apes, hands are also good at hand movements not involving grasping, like pushing, lifting, or tapping the keys of a typewriter or piano.[20]

Clinical significance

[edit]

A number of genetic disorders affect the hand. Polydactyly is the presence of more than the usual number of fingers. One of the disorders that can cause this is Catel-Manzke syndrome. The fingers may be fused in a disorder known as syndactyly. Or there may be an absence of one or more central fingers—a condition known as ectrodactyly. Additionally, some people are born without one or both hands (amelia). Hereditary multiple exostoses of the forearm—also known as hereditary multiple osteochondromas—is another cause of hand and forearm deformity in children and adults.[21]

There are several cutaneous conditions that can affect the hand including the nails.

The autoimmune disease rheumatoid arthritis can affect the hand, particularly the joints of the fingers.

Some conditions can be treated by hand surgery. These include carpal tunnel syndrome, a painful condition of the hand and fingers caused by compression of the median nerve, and Dupuytren's contracture, a condition in which fingers bend towards the palm and cannot be straightened. Similarly, injury to the ulnar nerve may result in a condition in which some of the fingers cannot be flexed.

A common fracture of the hand is a scaphoid fracture—a fracture of the scaphoid bone, one of the carpal bones. This is the commonest carpal bone fracture and can be slow to heal due to a limited blood flow to the bone. There are various types of fracture to the base of the thumb; these are known as Rolando fractures, Bennet's fracture, and Gamekeeper's thumb. Another common fracture, known as Boxer's fracture, is to the neck of a metacarpal. One can also have a broken finger.

Evolution

[edit]

The prehensile hands and feet of primates evolved from the mobile hands of semi-arboreal tree shrews that lived about 60 million years ago. This development has been accompanied by important changes in the brain and the relocation of the eyes to the front of the face, together allowing the muscle control and stereoscopic vision necessary for controlled grasping. This grasping, also known as power grip, is supplemented by the precision grip between the thumb and the distal finger pads made possible by the opposable thumbs. Hominidae (great apes including humans) acquired an erect bipedal posture about 3.6 million years ago, which freed the hands from the task of locomotion and paved the way for the precision and range of motion in human hands.[22] Functional analyses of the features unique to the hand of modern humans have shown that they are consistent with the stresses and requirements associated with the effective use of Paleolithic stone tools.[23] It is possible that the refinement of the bipedal posture in the earliest hominids evolved to facilitate the use of the trunk as leverage in accelerating the hand.[24]

While the human hand has unique anatomical features, including a longer thumb and fingers that can be controlled individually to a higher degree, the hands of other primates are anatomically similar and the dexterity of the human hand can not be explained solely on anatomical factors. The neural machinery underlying hand movements is a major contributing factor; primates have evolved direct connections between neurons in cortical motor areas and spinal motoneurons, giving the cerebral cortex monosynaptic control over the motoneurons of the hand muscles; placing the hands "closer" to the brain.[25] The recent evolution of the human hand is thus a direct result of the development of the central nervous system, and the hand, therefore, is a direct tool of our consciousness—the main source of differentiated tactile sensations—and a precise working organ enabling gestures—the expressions of our personalities.[26]

There are nevertheless several primitive features left in the human hand, including pentadactyly (having five fingers), the hairless skin of the palm and fingers, and the os centrale found in human embryos, prosimians, and apes. Furthermore, the precursors of the intrinsic muscles of the hand are present in the earliest fishes, reflecting that the hand evolved from the pectoral fin and thus is much older than the arm in evolutionary terms.[22]

The proportions of the human hand are plesiomorphic (shared by both ancestors and extant primate species); the elongated thumbs and short hands more closely resemble the hand proportions of Miocene apes than those of extant primates.[27] Humans did not evolve from knuckle-walking apes,[28] and chimpanzees and gorillas independently acquired elongated metacarpals as part of their adaptation to their modes of locomotion.[29] Several primitive hand features most likely present in the chimpanzee–human last common ancestor (CHLCA) and absent in modern humans are still present in the hands of Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and Homo floresiensis. This suggests that the derived changes in modern humans and Neanderthals did not evolve until 2.5 to 1.5 million years ago or after the appearance of the earliest Acheulian stone tools, and that these changes are associated with tool-related tasks beyond those observed in other hominins.[30] The thumbs of Ardipithecus ramidus, an early hominin, are almost as robust as in humans, so this may be a primitive trait, while the palms of other extant higher primates are elongated to the extent that some of the thumb's original function has been lost (most notably in highly arboreal primates such as the spider monkey). In humans, the big toe is thus more derived than the thumb.[29]

There is a hypothesis suggesting the form of the modern human hand is especially conducive to the formation of a compact fist, presumably for fighting purposes. The fist is compact and thus effective as a weapon. It also provides protection for the fingers.[31][32][33] However, this is not widely accepted to be one of the primary selective pressures acting on hand morphology throughout human evolution, with tool use and production being thought to be far more influential.[23]

Additional images

[edit]-

Illustration of hand and wrist bones

-

Bones of the left hand. Volar surface.

-

Bones of the left hand. Dorsal surface.

-

Static adult human physical characteristics of the hand

-

X-ray showing joints

-

Hand bone anatomy

See also

[edit]- Dactylonomy

- Dermatoglyphics

- Finger-counting

- Finger tracking

- Handstand

- Hand strength

- Hand walking

- Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism

- Knuckle-walking

- Palmistry—fortune-telling based on lines in hand palms

- Manus (anatomy)

- Mudra—Hindu term for hand gestures

- Muscles of the hand

References

[edit]- ^ Thomas, Dorcas MacClintock; illustrated by J. Sharkey (2002). A natural history of raccoons. Caldwell, N.J.: Blackburn Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-930665-67-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Xu, X; Clark, JM; Mo, J; Choiniere, J; Forster, CA; Erickson, GM; Hone, DWE; Sullivan, C; Eberth, DA; Nesbitt, S; Zhao, Q; Hernandez, R; Jia, CK; Han, FL; Guo, Y (2009). "A Jurassic ceratosaur from China helps clarify avian digital homologies" (PDF). Nature. 459 (7249): 940–944. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..940X. doi:10.1038/nature08124. PMID 19536256. S2CID 4358448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Latash, Mark L. (2008). Synergy. Oxford University Press, US. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-0-19-533316-9.

- ^ Kivell, Tracy L.; Lemelin, Pierre; Richmond, Brian G.; Schmitt, Daniel (2016). The Evolution of the Primate Hand: Anatomical, Developmental, Functional, and Paleontological Evidence. Springer. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-1-4939-3646-5.

- ^ Goldfinger, Eliot (1991). Human Anatomy for Artists : The Elements of Form: The Elements of Form. Oxford University Press. pp. 177, 295. ISBN 9780199763108.

- ^ O'Rahilly, Ronan; Müller, Fabiola (1983). Basic Human Anatomy: A Regional Study of Human Structure. Saunders. p. 93. ISBN 9780721669908.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Hans-Martin; Lanz, Ulrich (2003). Surgical Anatomy of the Hand. Thieme. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-58890-007-4.

- ^ Marieb, Elaine N (2004). Human Anatomy & Physiology (Sixth ed.). Pearson PLC. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-321-20413-4.

- ^ "Body Segment Data". ExRx.net.

- ^ Tubiana, Raoul; Thomine, Jean-Michel; Mackin, Evelyn (1998). Examination of the Hand and Wrist (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-85317-544-2.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2007) Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ a b c d Tubiana, Raoul; Thomine, Jean-Michel; Mackin, Evelyn (1998). Examination of the Hand and Wrist (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 9–14. ISBN 978-1-85317-544-2.

- ^ Austin, Noelle M. (2005). "Chapter 9: The Wrist and Hand Complex". In Levangie, Pamela K.; Norkin, Cynthia C. (eds.). Joint Structure and Function: A Comprehensive Analysis (4th ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company. pp. 319–320. ISBN 978-0-8036-1191-7.

- ^ Dawson-Amoah, K.; Varacallo, M. (2022). "Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Hand Intrinsic Muscles". NCBI. PMID 30969632. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

- ^ a b c Jones, Lynette A.; Lederman, Susan J. (2006). "Structure of the Skin". Human hand function. Oxford University Press. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-19-517315-4.

- ^ Ross, Lawrence M.; Lamperti, Edward D., eds. (2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-58890-419-5.

- ^ Jones, Lynette A.; Lederman, Susan J. (2006). "Structure of the Skin". Human hand function. Oxford University Press. pp. 18–21. ISBN 978-0-19-517315-4.

- ^ "Web". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "web of fingers/ toes". Farlex Medical Dictionary. Farlex Partner Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Exploring Life Sciences. Vol. 6. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 474–475. ISBN 0-7614-7141-3.

- ^ EL-Sobky, Tamer A.; Samir, Shady; Atiyya, Ahmed Naeem; Mahmoud, Shady; Aly, Ahmad S.; Soliman, Ramy (2018). "Current paediatric orthopaedic practice in hereditary multiple osteochondromas of the forearm: a systematic review". SICOT-J. 4: 10. doi:10.1051/sicotj/2018002. PMC 5863686. PMID 29565244.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Hans-Martin; Lanz, Ulrich (2003). Surgical Anatomy of the Hand. Thieme. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-58890-007-4.

- ^ a b Key, Alastair J.M.; Lycett, Stephen J. (2011). "Technology based evolution? A biometric test of the effects of handsize versus tool form on efficiency in an experimental cutting task". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (7): 1663–1670. Bibcode:2011JArSc..38.1663K. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.02.032.

- ^ Marzke, Mary. "Evolution of the hand and bipedality". Massey University, NZ. Archived from the original on October 5, 1999. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Flanagan, J Randall; Johansson, Roland S (2002). "Hand Movements" (PDF). Encyclopedia of the human brain. Elsevier Science.

- ^ Putz, RV; Tuppek, A. (November 1999). "Evolution of the hand". Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 31 (6): 357–61. doi:10.1055/s-1999-13552. PMID 10637723.

- ^ Almécija, Sergio (2009). Evolution of the hand in Miocene apes: Implications for the appearance of the human hand (PhD thesis). Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. hdl:10803/3707. ISBN 978-84-693-4823-9. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ Kivella, Tracy L.; Schmitt, Daniel (August 25, 2009). "Independent evolution of knuckle-walking in African apes shows that humans did not evolve from a knuckle-walking ancestor". PNAS. 106 (34): 14241–14246. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10614241K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901280106. PMC 2732797. PMID 19667206.

- ^ a b Lovejoy, C. Owen; Suwa, Gen; Simpson, Scott W.; Matternes, Jay H.; White, Tim D. (October 2009). "The Great Divides: Ardipithecus ramidus Reveals the Postcrania of Our Last Common Ancestors with African Apes". Science. 326 (5949): 101–102. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..100L. doi:10.1126/science.1175833. PMID 19810199. S2CID 19629241.

- ^ Tocheri, Matthew W.; Orr, Caley M.; Jacofsky, Marc C.; Marzke, Mary W. (2008). "The evolutionary history of the hominin hand since the last common ancestor of Pan and Homo" (PDF). J. Anat. 212 (4): 544–562. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00865.x. PMC 2409097. PMID 18380869. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-09. Retrieved 2011-12-25.)

- ^ Reardon, Sara (December 19, 2012). "Human hands evolved so we could punch each other". New Scientist. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Knight, Kathryn (2012). "Fighting Shaped Human Hands". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (2): i.1–i. doi:10.1242/jeb.083725.

- ^ Morgan, Michael H.; Carrier, David R. (January 2013). "Protective buttressing of the human fist and the evolution of hominin hands". J Exp Biol. 216 (2): 236–244. Bibcode:2013JExpB.216..236M. doi:10.1242/jeb.075713. PMID 23255192.