Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Serous membrane

View on Wikipedia| Serous membrane | |

|---|---|

Stomach. (Serosa is labeled at far right, and is colored yellow.) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Mesoderm |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tunica serosa |

| MeSH | D012704 |

| FMA | 9581 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| This article is one of a series on the |

| Gastrointestinal wall |

|---|

The serous membrane (or serosa) is a smooth epithelial membrane of mesothelium lining the contents and inner walls of body cavities, which secrete serous fluid to allow lubricated sliding movements between opposing surfaces. The serous membrane that covers internal organs (viscera) is called visceral, while the one that covers the cavity wall is called parietal. For instance the parietal peritoneum is attached to the abdominal wall and the pelvic walls.[2] The visceral peritoneum is wrapped around the visceral organs. For the heart, the layers of the serous membrane are called parietal and visceral pericardium. For the lungs they are called parietal and visceral pleura. The visceral serosa of the uterus is called the perimetrium. The potential space between two opposing serosal surfaces is mostly empty except for the small amount of serous fluid.[3]

The Latin anatomical name is tunica serosa. Serous membranes line and enclose several body cavities, also known as serous cavities, where they secrete a lubricating fluid which reduces friction from movements. Serosa is entirely different from the adventitia, a connective tissue layer which binds together structures rather than reducing friction between them. The serous membrane covering the heart and lining the mediastinum is referred to as the pericardium, the serous membrane lining the thoracic cavity and surrounding the lungs is referred to as the pleura, and that lining the abdominopelvic cavity and the viscera is referred to as the peritoneum.

Structure

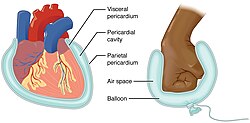

[edit]Serous membranes have two layers. The parietal layers of the membranes line the walls of the body cavity (pariet- refers to a cavity wall). The visceral layer of the membrane covers the organs (the viscera). Between the parietal and visceral layers is a very thin, fluid-filled serous space, or cavity.[4]

Visceral and parietal layers

[edit]Each serous membrane is composed of a secretory epithelial layer and a connective tissue layer underneath.

- The epithelial layer, known as mesothelium, consists of a single layer of avascular flat nucleated cells (simple squamous epithelium) which produce the lubricating serous fluid. This fluid has a consistency similar to thin mucus. These cells are bound tightly to the underlying connective tissue.

- The connective tissue layer provides the blood vessels and nerves for the overlying secretory cells, and also serves as the binding layer which allows the whole serous membrane to adhere to organs and other structures.

For the heart, the layers of the serous membrane are called the parietal pericardium, and the visceral pericardium (sometimes called the epicardium). Other parts of the body may also have specific names for these structures. For example, the serosa of the uterus is called the perimetrium.

The pericardial cavity (surrounding the heart), pleural cavity (surrounding the lungs) and peritoneal cavity (surrounding most organs of the abdomen) are the three serous cavities within the human body. While serous membranes have a lubricative role to play in all three cavities, in the pleural cavity it has a greater role to play in the function of breathing.

The serous cavities are formed from the intraembryonic coelom and are basically an empty space within the body surrounded by serous membrane. Early in embryonic life visceral organs develop adjacent to a cavity and invaginate into the bag-like coelom. Therefore, each organ becomes surrounded by serous membrane - they do not lie within the serous cavity. The layer in contact with the organ is known as the visceral layer, while the parietal layer is in contact with the body wall.

Examples

[edit]In the human body, there are three serous cavities with associated serous membranes:

- A serous membrane lines the pericardial cavity of the heart, and reflects back to cover the heart, much like an under-inflated balloon would form two layers surrounding a fist. Called the pericardium, this serous membrane is a two-layered sac that surrounds the entire heart except where blood vessels emerge on the heart's superior side;[4]

- The pleura is the serous membrane that surrounds the lungs in the pleural cavity;

- The peritoneum is the serous membrane that surrounds several organs in the abdominopelvic cavity.

- The tunica vaginalis is the serous membrane, which surrounds the male gonad, the testis.

The two layers of serous membranes are named parietal and visceral. Between the two layers is a thin fluid filled space.[4] The fluid is produced by the serous membranes and stays between the two layers to reduce friction between the walls of the cavities and the internal organs when they move with respect to one another, such as when the lungs inflate or the heart beats. Such movement could otherwise lead to inflammation of the organs.[4]

Development

[edit]All serous membranes found in the human body are formed ultimately from the mesoderm of the trilaminar embryo. The trilaminar embryo consists of three relatively flat layers of ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm.

As the embryo develops, the mesoderm starts to segment into three main regions: the paraxial mesoderm, the intermediate mesoderm and the lateral plate mesoderm.

The lateral plate mesoderm later splits in half to form two layers bounding a cavity known as the intraembryonic coelom. Individually, each layer is known as splanchnopleure and somatopleure.

- The splanchnopleure is associated with the underlying endoderm with which it is in contact, and later becomes the serous membrane in contact with visceral organs within the body.

- The somatopleure is associated with the overlying ectoderm and later becomes the serous membrane in contact with the body wall.

The intraembryonic coelom can now be seen as a cavity within the body which is covered with serous membrane derived from the splanchnopleure. This cavity is divided and demarcated by the folding and development of the embryo, ultimately forming the serous cavities which house many different organs within the thorax and abdomen.

Diseases

[edit]Mesotheliomas are neoplasms that are relatively specific for serous membranes. The modified Müllerian-derived serous membranes that surrounds the ovaries in females can give rise to serous tumors, a solid to papillary tumor type that may also arise within the uterus.

Anatomical images

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]This Wikipedia entry incorporates text from the freely licensed Connexions [1] edition of Anatomy & Physiology [2] text-book by OpenStax College

- ^ J. Gordon Betts; Kelly A. Young; James A. Wise; Eddie Johnson; Brandon Poe; Dean H. Kruse; Oksana Korol; Jody E. Johnson; Mark Womble; Peter DeSaix (Apr 25, 2013). "1.6 Anatomical Terminology". Anatomy and Physiology. Houston, Texas: OpenStax.

- ^ Tank PW (2013). "Chapter 4: The abdomen". Grant's dissector (Fifteenth ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-60913-606-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Anatomy of Lining and Covering Tissues-Membranes!". McGraw-Hill Companies. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Anatomy & Physiology". Openstax college at Connexions. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

External links

[edit]- UIUC Histology Subject 844

- Parsons, Frederick Gymer (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). pp. 642–644.