Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Classic of Poetry

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Classic of Poetry | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

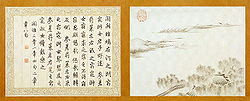

"Classic of Poetry" in seal script (top),[a] Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 詩經 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 诗经 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Kinh Thi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 經詩 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 시경 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 詩經 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | しきょう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyūjitai | 詩經 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 詩経 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Confucianism |

|---|

|

The Classic of Poetry, also Shijing or Shih-ching, translated variously as the Book of Songs, Book of Odes, or simply known as the Odes or Poetry (詩; Shī), is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, comprising 305 works dating from the 11th to 7th centuries BC. It is one of the "Five Classics" traditionally said to have been edited by Confucius, and has been studied and memorized by scholars in China and neighboring countries over two millennia. It is also a rich source of chengyu (four-character classical idioms) that are still a part of learned discourse and even everyday language in modern Chinese. Since the Qing dynasty, its rhyme patterns have also been analysed in the study of Old Chinese phonology.

Name

[edit]Early references refer to the anthology as the 300 Poems (shi). The Odes first became known as a jīng, or a "classic book", in the canonical sense, as part of the Han dynasty's official adoption of Confucianism as the guiding principle of Chinese society.[citation needed] The same word shi later became a generic term for poetry.[1] In English, lacking an exact equivalent for the Chinese, the translation of the word shi in this regard is generally as "poem", "song", or "ode". Before its elevation as a canonical classic, the Classic of Poetry (Shi jing) was known as the Three Hundred Songs or the Songs.[2]

Content

[edit]The Classic of Poetry contains the oldest chronologically authenticated Chinese poems.[1] The majority of the Odes date to the Western Zhou period (1046–771 BCE), and were drawn from around provinces and cities in the Zhongyuan (Central Plains) area. A final section of 5 "Eulogies of Shang" purports to be ritual songs of the Shang dynasty as handed down by their descendants in the state of Song, but is generally considered quite late in date.[3][4] According to the Eastern Han scholar Zheng Xuan, the latest material in the Shijing was the song "Tree-Stump Grove" (株林) in the "Odes of Chen", dated to the middle of the Spring and Autumn period (c. 700 BCE).[5]

| Part | Number and meaning | Date (BCE)[6][7] |

|---|---|---|

| 國風 Guó fēng | 160 "Airs of the States" | 8th & 7th century |

| 小雅 Xiǎo yǎ | 74 "Lesser Court Hymns" | 9th & 8th century |

| 大雅 Dà yǎ | 31 "Major Court Hymns" | 10th & 9th century |

| 周頌 Zhōu sòng | 31 "Eulogies of Zhou" | 11th & 10th century |

| 魯頌 Lǔ sòng | 4 "Eulogies of Lu" | 7th century |

| 商頌 Shāng sòng | 5 "Eulogies of Shang" | 7th century |

The content of the Poetry can be divided into two main sections: the "Airs of the States", and the "Eulogies" and "Hymns".[8]

The "Airs of the States" are shorter lyrics in simple language that are generally ancient folk songs which record the voice of the common people.[8] They often speak of love and courtship, longing for an absent lover, soldiers on campaign, farming and housework, and political satire and protest.[8] The first song of the "Airs of the States", "Fishhawk" (Guān jū 關雎), is a well-known example of the category. Confucius commented on it, and it was traditionally given special interpretive weight.[9]

The fishhawks sing gwan-gwan

On sandbars of the stream.

Gentle maiden, pure and fair,

Fit pair for a prince.

Watercress grows here and there,

Right and left we gather it.

Gentle maiden, pure and fair,

Wanted waking and sleep.

Wanting, sought her, had her not,

Waking, sleeping, thought of her,

On and on he thought of her,

He tossed from one side to another.

Watercress grows here and there,

Right and left we pull it.

Gentle maiden, pure and fair,

With harps we bring her company.

Watercress grows here and there,

Right and left we pick it out.

Gentle maiden, pure and fair,

With bells and drums do her delight.

關關雎鳩

在河之洲

窈窕淑女

君子好逑

參差荇菜

左右流之

窈窕淑女

寤寐求之

求之不得

寤寐思服

悠哉悠哉

輾轉反側

參差荇菜

左右采之

窈窕淑女

琴瑟友之

參差荇菜

左右芼之

窈窕淑女

鐘鼓樂之

On the other hand, songs in the two "Hymns" sections and the "Eulogies" section tend to be longer ritual or sacrificial songs, usually in the forms of courtly panegyrics and dynastic hymns which praise the founders of the Zhou dynasty.[8] They also include hymns used in sacrificial rites and songs used by the aristocracy in their sacrificial ceremonies or at banquets.[11][12]

"Court Hymns" contains "Lesser Court Hymns" and "Major Court Hymns". Most of the poems were used by the aristocrats to pray for good harvests each year, worship gods, and venerate their ancestors. The authors of "Major Court Hymns" are nobles who were dissatisfied with the political reality. Therefore, they wrote poems not only related to the feast, worship, and epic but also to reflect the public feelings.[13]

Ah! Solemn is the clear temple,

Reverent and concordant the illustrious assistants.

Dignified, dignified are the many officers,

Holding fast to the virtue of King Wen.

Responding in praise to the one in Heaven,

They hurry swiftly within the temple.

Greatly illustrious, greatly honored,

May [King Wen] never be weary of [us] men.

於穆清廟

肅雝顯相

濟濟多士

秉文之德

對越在天

駿奔走在廟

不顯不承

無射於人斯

Style

[edit]Whether the various Shijing poems were folk songs or not, they "all seem to have passed through the hands of men of letters at the royal Zhou court".[15] In other words, they show an overall literary polish together with some general stylistic consistency. About 95% of lines in the Poetry are written in a four-syllable meter, with a slight caesura between the second and third syllables.[8] Lines tend to occur in syntactically related couplets, with occasional parallelism, and longer poems are generally divided into similarly structured stanzas.[16]

All but six of the "Eulogies" consist of a single stanza, and the "Court Hymns" exhibit wide variation in the number of stanzas and their lengths. Almost all of the "Airs", however, consist of three stanzas, with four-line stanzas being most common.[17][18] Although a few rhyming couplets occur, the standard pattern in such four-line stanzas required a rhyme between the second and fourth lines. Often the first or third lines would rhyme with these, or with each other.[19] This style later became known as the "shi" style for much of Chinese history.

One of the characteristics of the poems in the Classic of Poetry is that they tend to possess "elements of repetition and variation".[16] This results in an "alteration of similarities and differences in the formal structure: in successive stanzas, some lines and phrases are repeated verbatim, while others vary from stanza to stanza".[20] Characteristically, the parallel or syntactically matched lines within a specific poem share the same, identical words (or characters) to a large degree, as opposed to confining the parallelism between lines to using grammatical category matching of the words in one line with the other word in the same position in the corresponding line; but, not by using the same, identical word(s).[16] Disallowing verbal repetition within a poem would by the time of Tang poetry be one of the rules to distinguish the old style poetry from the new, regulated style.

The works in the Classic of Poetry vary in their lyrical qualities, which relates to the musical accompaniment with which they were in their early days performed. The songs from the "Hymns" and "Eulogies", which are the oldest material in the Poetry, were performed to slow, heavy accompaniment from bells, drums, and stone chimes.[8] However, these and the later actual musical scores or choreography which accompanied the Shijing poems have been lost.

Nearly all of the songs in the Poetry are rhyming, with end rhyme, as well as frequent internal rhyming.[16] While some of these verses still rhyme in modern varieties of Chinese, others had ceased to rhyme by the Middle Chinese period. For example, the eighth song (芣苢 Fú Yǐ[b]) has a tightly constrained structure implying rhymes between the penultimate words (here shown in bold) of each pair of lines:[21]

|

Chinese characters 采采芣苢、薄言采之。 |

Pinyin transliteration Cǎi cǎi fú yǐ, báo yán cǎi zhī. |

Early Middle Chinese (Baxter) tshojX tshojX bju yiX, bak ngjon tshojX tsyi. |

The second and third stanzas still rhyme in modern Standard Chinese, with the rhyme words even having the same tone, but the first stanza does not rhyme in Middle Chinese or any modern variety. Such cases were attributed to lax rhyming practice until the late-Ming dynasty scholar Chen Di argued that the original rhymes had been obscured by sound change. Since Chen, scholars have analyzed the rhyming patterns of the Poetry as crucial evidence for the reconstruction of Old Chinese phonology.[22] For instance, 采; cǎi and 有; yǒu in the above example are reconstructed to share the same rhyme, *-əʔ, in Schuessler's "Minimal Old Chinese" (as *tsʰə̂ʔ and *wəʔ respectively)[23] as well as in Baxter and Sagart's Old Chinese reconstruction (as *s.r̥ˤəʔ and *[ɢ]ʷəʔ respectively).[24]

Traditional scholarship of the Poetry identified three major literary devices employed in the songs: straightforward narrative (賦; fù), explicit comparisons (比; bǐ) and implied comparisons (興; xìng). The poems of the Classic of Poetry tend to have certain typical patterns in both rhyme and rhythm, to make much use of imagery, often derived from nature.

Authorship

[edit]Although the Shijing does not specify the names of authors in association with the contained works, both traditional commentaries and modern scholarship have put forth hypotheses on authorship. The "Golden Coffer" chapter of the Book of Documents says that the poem "Owl" (鴟鴞) in the "Odes of Bin" was written by the Duke of Zhou. Many of the songs appear to be folk songs and other compositions used in the court ceremonies of the aristocracy.[11] Furthermore, many of the songs, based on internal evidence, appear to be written either by women, or from the perspective of a female persona. The repeated emphasis on female authorship of poetry in the Shijing was made much of in the process of attempting to give the poems of the women poets of the Ming-Qing period canonical status.[25] Despite the impersonality of the poetic voice characteristic of the Songs,[26] many of the poems are written from the perspective of various generic personalities.

Textual history

[edit]

According to tradition, the method of collection of the various Shijing poems involved the appointment of officials, whose duties included documenting verses current from the various states which constituted the empire. Out of these many collected pieces, also according to tradition, Confucius made a final editorial round of decisions for elimination or inclusion in the received version of the Poetry. As with all great literary works of ancient China, the Poetry has been annotated and commented on continuously throughout history, as well as in this case providing a model to inspire future poetic works.

Various traditions concern the gathering of the compiled songs and the editorial selection from these make up the classic text of the Odes: "Royal Officials' Collecting Songs" (王官采詩) is recorded in the Book of Han,[c] and "Master Confucius Deletes Songs" (孔子刪詩) refers to Confucius and his mention in the Records of the Grand Historian, where it says from originally some 3,000 songs and poems in a previously extant "Odes" that Confucius personally selected the "300" which he felt best conformed to traditional ritual propriety, thus producing the Classic of Poetry.

In 2015, Anhui University purchased a group of looted manuscripts dating to c. 330 BC (during the Warring States period), among which is one of the oldest extant scribal copies of the Classic of Poetry (at least part of it). The manuscript has been published in the first volume of this collection of manuscripts, Anhui daxue cang Zhanguo zhujian (安徽大學藏戰國竹簡).[27]

Compilation

[edit]The Confucian school eventually came to consider the verses of the "Airs of the States" to have been collected in the course of activities of officers dispatched by the Zhou dynasty court, whose duties included the field collection of the songs local to the territorial states of Zhou.[1] This territory was roughly the Yellow River Plain, Shandong, southwestern Hebei, eastern Gansu, and the Han River region. Perhaps during the harvest. After the officials returned from their missions, the king was said to have observed them himself in an effort to understand the current condition of the common people.[1] The well-being of the people was of special concern to the Zhou because of their ideological position that the right to rule was based on the benignity of the rulers to the people in accordance with the will of Heaven, and that this Heavenly Mandate would be withdrawn upon the failure of the ruling dynasty to ensure the prosperity of their subjects.[28] The people's folksongs were deemed to be the best gauge of their feelings and conditions, and thus indicative of whether the nobility was ruling according to the mandate of Heaven or not. Accordingly, the songs were collected from the various regions, converted from their diverse regional dialects into standard literary language, and presented accompanied with music at the royal courts.[29]

Confucius

[edit]The Classic of Poetry historically has a major place in the Four Books and Five Classics, the canonical works associated with Confucianism.[30] Some pre-Qin dynasty texts, such as the Analects and a recently excavated manuscript from 300 BCE entitled "Confucius' Discussion of the Odes", mention Confucius' involvement with the Classic of Poetry but Han dynasty historian Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian was the first work to directly attribute the work to Confucius.[31] Subsequent Confucian tradition held that the Shijing collection was edited by Confucius from a larger 3,000-piece collection to its traditional 305-piece form.[32] This claim is believed to reflect an early Chinese tendency to relate all of the Five Classics in some way or another to Confucius, who by the 1st century BCE had become the model of sages and was believed to have maintained a cultural connection to the early Zhou dynasty.[31] This view is now generally discredited, as the Zuo zhuan records that the Classic of Poetry already existed in a definitive form when Confucius was just a young child.[11]

In works attributed to him, Confucius comments upon the Classic of Poetry in such a way as to indicate that he holds it in great esteem. A story in the Analects recounts that Confucius' son Kong Li told the story: "The Master once stood by himself, and I hurried to seek teaching from him. He asked me, 'You've studied the Odes?' I answered, 'Not yet.' He replied, 'If you have not studied the Odes, then I have nothing to say.'"[33]

Han dynasty

[edit]According to Han tradition, the Poetry and other classics were targets of the burning of books in 213 BCE under Qin Shi Huang, and the songs had to be reconstructed largely from memory in the subsequent Han period. However the discovery of pre-Qin copies showing the same variation as Han texts, as well as evidence of Qin patronage of the Poetry, have led modern scholars to doubt this account.[34]

During the Han period there were three different versions of the Poetry which each belonged to different hermeneutic traditions.[35] The Lu Poetry (魯詩; Lǔ shī), the Qi Poetry (齊詩; Qí shī) and the Han Poetry (韓詩; Hán shī) were officially recognized with chairs at the Imperial Academy during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (156–87 BCE).[35] Until the later years of the Eastern Han period, the dominant version of the Poetry was the Lu Poetry, named after the state of Lu, and founded by Shen Pei, a student of a disciple of the Warring States period philosopher Xunzi.[35]

The Mao Tradition of the Poetry (毛詩傳; Máo shī zhuàn), attributed to an obscure scholar named Máo Hēng (毛亨) who lived during the 2nd or 3rd centuries BCE,[35] was not officially recognized until the reign of Emperor Ping (1 BCE to 6 CE).[36] However, during the Eastern Han period, the Mao Poetry gradually became the primary version.[35] Proponents of the Mao Poetry said that its text was descended from the first generation of Confucius' students, and as such should be the authoritative version.[35] Xu Shen's influential dictionary Shuowen Jiezi, written in the 2nd-century CE, quotes almost exclusively from the Mao Poetry.[35] Finally, the renowned Eastern Han scholar Zheng Xuan used the Mao Poetry as the basis for his annotated 2nd-century edition of the Poetry. Zheng Xuan's edition of the Mao text was itself the basis of the "Right Meaning of the Mao Poetry" (毛詩正義; Máo shī zhèngyì) which became the imperially authorized text and commentary on the Poetry in 653 CE.[35]

By the 5th-century, the Lu, Qi, and Han traditions had died out, leaving only the Mao Poetry, which has become the received text in use today.[34] Only isolated fragments of the Lu text survive, among the remains of the Xiping Stone Classics.[36]

Legacy

[edit]Confucian allegory

[edit]

The Book of Odes has been a revered Confucian classic since the Han dynasty, and has been studied and memorized by centuries of scholars in China.[12] The individual songs of the Odes, though frequently on simple, rustic subjects, have traditionally been saddled with extensive, elaborate allegorical meanings that assigned moral or political meaning to the smallest details of each line.[37] The popular songs were seen as good keys to understanding the troubles of the common people, and were often read as allegories, and complaints against lovers were seen as complaints against faithless rulers.[12][37] Confucius taught that the Odes were a valuable focus for knowledge and self-cultivation, as recorded in an anecdote in the Analects:

The Odes can be a source of inspiration and a basis for evaluation; they can help you to come together with others, as well as to properly express complaints. In the home, they teach you about how to serve your father, and in public life they teach you about how to serve your lord. They also broadly acquaint you with the names of birds, beasts, plants, and trees.

詩可以興,可以觀,可以群,可以怨。邇之事父,遠之事君。多識於鳥獸草木之名。

— Analects, chapter 17 (Edward Slingerland, trans.)[38]

The extensive allegorical traditions associated with the Odes were theorized by Herbert Giles to have begun in the Warring States period as a justification for Confucius' focus upon such a seemingly simple and ordinary collection of verses.[39] These elaborate, far-fetched interpretations seem to have gone completely unquestioned until the 12th century, when scholar Zheng Qiao (鄭樵, 1104–1162) first wrote his scepticism of them.[40] European sinologists like Giles and Marcel Granet ignored these traditional interpretations in their analysis of the original meanings of the Odes. Granet, in his list of rules for properly reading the Odes, wrote that readers should "take no account of the standard interpretation", "reject in no uncertain terms the distinction drawn between songs evicting a good state of morals and songs attesting to perverted morality", and "[discard] all symbolic interpretations, and likewise any interpretation that supposes a refined technique on the part of the poets".[41] These traditional allegories of politics and morality are no longer seriously followed by any modern readers in China or elsewhere.[40]

Political influence

[edit]The Odes became an important and controversial force, influencing political, social and educational phenomena.[42] During the struggle between Confucian, Legalist, and other schools of thought, the Confucians used the Shijing to bolster their viewpoint.[42] On the Confucian side, the Shijing became a foundational text which informed and validated literature, education, and political affairs.[43] The Legalists, on their side, attempted to suppress the Shijing by violence, after the Legalist philosophy was endorsed by the Qin dynasty, prior to their final triumph over the neighboring states: the suppression of Confucian and other thought and literature after the Qin victories and the start of Burning of Books and Burying of Scholars era, starting in 213 BCE, extended to attempt to prohibit the Shijing.[42]

As the idea of allegorical expression grew, when kingdoms or feudal leaders wished to express or validate their own positions, they would sometimes couch the message within a poem, or by allusion. This practice became common among educated Chinese in their personal correspondences and spread to Japan and Korea as well.

Modern scholarship

[edit]Modern scholarship on the Classic of Poetry often focuses on doing linguistic reconstruction and research in Old Chinese by analyzing the rhyme schemes in the Odes, which show vast differences when read in modern Mandarin Chinese.[21] Although preserving more Old Chinese syllable endings than Mandarin, Modern Cantonese and Min Nan are also quite different from the Old Chinese language represented in the Odes.[44]

C.H. Wang refers to the account of King Wu's victory over the Shang dynasty in the "Major Court Hymns" as the "Weniad" (a name that parallels The Iliad), seeing it as part of a greater narrative discourse in China that extols the virtues of wén (文 "literature, culture") over more military interests.[45]

Marquis of Haihun's tomb

[edit]A copy of the Book of Songs was recently found in the Marquis of Haihun's tomb (Chinese: 海昏侯墓; pinyin: Hǎihūn hóu mù) in Jiangxi Province. This find from a Chinese imperial tomb includes bamboo slips that form a nearly intact edition.[46]

Contents list

[edit]| group | char | group name | poem #s |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 周南 | Odes of Zhou & South | 001–011 |

| 02 | 召南 | Odes of Shao & South | 012–025 |

| 03 | 邶風 | Odes of Bei | 026–044 |

| 04 | 鄘風 | Odes of Yong | 045–054 |

| 05 | 衛風 | Odes of Wei | 055–064 |

| 06 | 王風 | Odes of Wang | 065–074 |

| 07 | 鄭風 | Odes of Zheng | 075–095 |

| 08 | 齊風 | Odes of Qi | 096–106 |

| 09 | 魏風 | Odes of Wei | 107–113 |

| 10 | 唐風 | Odes of Tang | 114–125 |

| 11 | 秦風 | Odes of Qin | 126–135 |

| 12 | 陳風 | Odes of Chen | 136–145 |

| 13 | 檜風 | Odes of Kuai | 146–149 |

| 14 | 曹風 | Odes of Cao | 150–153 |

| 15 | 豳風 | Odes of Bin | 154–160 |

| group | char | group name | poem #s |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 鹿鳴 之什 | Decade of Lu Ming | 161–169 |

| 02 | 白華 之什 | Decade of Baihua | 170–174 |

| 03 | 彤弓 之什 | Decade of Tong Gong | 175–184 |

| 04 | 祈父 之什 | Decade of Qi Fu | 185–194 |

| 05 | 小旻 之什 | Decade of Xiao Min | 195–204 |

| 06 | 北山 之什 | Decade of Bei Shan | 205–214 |

| 07 | 桑扈 之什 | Decade of Sang Hu | 215–224 |

| 08 | 都人士 之什 | Decade of Du Ren Shi | 225–234 |

| group | char | group name | poem #s |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 文王之什 | Decade of Wen Wang | 235–244 |

| 02 | 生民之什 | Decade of Sheng Min | 245–254 |

| 03 | 蕩之什 | Decade of Dang | 255–265 |

| group | char | group name | poem #s |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 周頌 | Sacrificial Odes of Zhou | 266–296 |

| 01a | 清廟之什 | Decade of Qing Miao | 266–275 |

| 01b | 臣工之什 | Decade of Chen Gong | 276–285 |

| 01c | 閔予小子之什 | Decade of Min You Xiao Zi | 286–296 |

| 02 | 魯頌 | Praise Odes of Lu | 297–300 |

| 03 | 商頌 | Sacrificial Odes of Shang | 301–305 |

Note: alternative divisions may be topical or chronological (Legge): Song, Daya, Xiaoya, Guofeng

Notable translations

[edit]- Legge, James (1871). The She-king, or the Lessons from the States. The Chinese Classics. Vol. 4. Part 1, Part 2. rpt. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press (1960).

- —— (1876). The She king, or The Book of Ancient Poetry (PDF). London: Trübner. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-12.

- —— (1879). The Shû king. The religious portions of the Shih king. The Hsiâo king. The Sacred Books of China. Vol. 3. Oxford, The Clarendon press.

- Lacharme, P. (1830). Confucii Chi-King sive Liber Carminum. Sumptibus J.G. Cottae. Latin translation.

- Jennings, William (1891). The Shi King: The Old "Poetry Classic" of the Chinese.; rpt. New York: Paragon (1969).

- (in French and Latin) Couvreur, Séraphin (1892). Cheu-king; Texte chinois avec une double traduction en français et en Latin [Shijing; Chinese Text With a Double Translation in French and Latin]. Hokkien: Mission Catholique.

- Granet, Marcel (1929). Fêtes et chansons anciennes de la Chine (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Translated into English by E. D. Edwards (1932), Festivals and Songs of Ancient China, New York: E.P. Dutton. - Waley, Arthur (1937). The Book of Songs. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9780802134776.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) Rpt. New York: Grove Press, 1996, with a Preface by Joseph Allen. ISBN 0802134777. - Karlgren, Bernhard (1950). The Book of Odes (PDF). Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Reprint of

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1944). "The Book of Odes: Kuo Feng and Siao Ya". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 16: 171–256.

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1945). "The Book of Odes: Ta Ya and Sung". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 17: 65–99.

- Pound, Ezra (1954). The Confucian Odes: The Classic Anthology Defined by Confucius. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Takada, Shinji 高田真治 (1966). Shikyō 詩経 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shūeisha.

- (in Mandarin Chinese) Cheng Junying 程俊英 (1985). Shijing Yizhu 诗经译注 [Shijing, Translated and Annotated]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe and

- (in Mandarin Chinese) Cheng Junying 程俊英 (1991). Shijing Zhuxi 詩經注析 [Shijing, Annotation and Analysis]. Zhonghua Publishing House.[1]

- (in Japanese) Mekada, Makoto 目加田誠 (1991). Shikyō 詩経. Tokyo: Kōbansha.

- Vincenzo, Cannata (2021). Il Libro delle Odi: edizione integrale. Milano, Italy: Luni Editrice.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c The *k-lˤeng (jing 經) appellation would not have been used until the Han dynasty, after the core Old Chinese period.

- ^ The variant character 苡 may sometimes be used in place of 苢, in which case the title is 芣苡, with corresponding substitutions for the fourth character of each line within the body of the poem.

- ^ In the 食貨志.; Shi Huo Zhi

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Davis (1970), p. xliii.

- ^ Hawkes (2011), p. 25.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 356.

- ^ Allan (1991), p. 39.

- ^ Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (AD 127–200), Shipu xu 詩譜序.

- ^ Dobson (1964), p. 323.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 355–356.

- ^ a b c d e f Kern (2010), p. 20.

- ^ Owen (1996), p. 31.

- ^ Owen (1996), pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c de Bary & Chan (1960), p. 3.

- ^ a b c Ebrey (1993), pp. 11–13.

- ^ Shi & Hu (2011).

- ^ Kern (2010), p. 23.

- ^ Frankel (1978), p. 215–216.

- ^ a b c d Frankel (1978), p. 216.

- ^ Riegel (2001), p. 107.

- ^ Nylan (2001), pp. 73–74.

- ^ Riegel (2001), pp. 107–108.

- ^ Frankel (1978), p. 51–52.

- ^ a b Baxter (1992), pp. 150–151.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 150–155.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 175, 580.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 330, 372.

- ^ Chang (2001), p. 2.

- ^ Yip (1997), p. 54.

- ^ Smith & Poli (2021), p. 516.

- ^ Hinton (2008), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Hinton (2008), p. 8.

- ^ Frankel (1978), p. 215.

- ^ a b Kern (2010), p. 19.

- ^ Idema & Haft (1997), p. 94.

- ^ Analects 16.13.

- ^ a b Kern (2010), p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kern (2010), p. 21.

- ^ a b Loewe (1993), p. 416.

- ^ a b Giles (1901), pp. 12–14.

- ^ Jenco (2023), p. 671.

- ^ Cited in Saussy (1993), p. 19.

- ^ a b Saussy (1993), p. 20.

- ^ Granet (1929), cited in Saussy (1993), p. 20.

- ^ a b c Davis (1970), p. xlv.

- ^ Davis (1970), p. xliv.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 1–12.

- ^ Wang (1975), pp. 26–29.

- ^ "海昏侯墓首次发现秦汉时期全本《诗经》". www.stdaily.com. Retrieved 2025-11-18.

Works cited

[edit]- Allan, Sarah (1991), The Shape of the Turtle: Myth, Art, and Cosmos in Early China, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-0460-7.

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014). Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Chang, Kang-i Sun (2001), "Gender and Canonicity", in Fong, Grace S. (ed.), Hsiang Lectures on Chinese Poetry, vol. 1, Montreal: Center for East Asian Research, McGill University.

- Davis, Albert Richard, ed. (1970), The Penguin Book of Chinese Verse, Baltimore: Penguin Books.

- de Bary, William Theodore; Chan, Wing-Tsit (1960), Sources of Chinese Tradition: Volume I, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-10939-0.

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Dobson, W. A. C. H. (1964), "Linguistic Evidence and the Dating of the Book of Songs", T'oung Pao, 51 (4–5): 322–334, doi:10.1163/156853264x00028, JSTOR 4527607.

- Ebrey, Patricia (1993), Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook (2nd ed.), The Free Press, ISBN 978-0-02-908752-7.

- Frankel, Hans H. (1978), The Flowering Plum and the Palace Lady, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-02242-1.

- Giles, Herbert (1901), A History of Chinese Literature, New York: Appleton-Century.

- Granet, Marcel (1929), Fêtes et chansons anciennes de la Chine [Ancient Festivals and Songs of China], Paris: Leroux.

- Hawkes, David, ed. (2011) [1985], The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2.

- Hinton, David (2008), Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, ISBN 978-0-374-10536-5.

- Idema, Wilt L.; Haft, Lloyd (1997), A Guide to Chinese Literature, Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, ISBN 978-0-892-64123-9.

- Jenco, Leigh (2023). "Chen Di's Investigations of the Ancient Pronunciations of the Mao Odes (Mao Shi guyin kao) and Textual Research in the Late Ming". T'oung Pao. 109 (5/6): 668–704. doi:10.1163/15685322-10905006.

- Kern, Martin (2005), "The Odes in Excavated Manuscripts" (PDF), in Kern, Martin (ed.), Text and Ritual in Early China, Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 149–193, ISBN 978-0-295-98562-6.

- Kern, Martin (2010), "Early Chinese Literature, Beginnings Through Western Han", in Owen, Stephen (ed.), The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, vol. 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–115, ISBN 978-0-521-85558-7.

- Knechtges, David R.; Shih, Hsiang-ling (2014). "Shijing 詩經". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part Two. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 904–915. ISBN 978-90-04-19240-9.

- Loewe, Michael (1993), "Shih ching 詩經", in Loewe, Michael (ed.), Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide, Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California Berkeley, pp. 415–423, ISBN 978-1-55729-043-4.

- Nylan, Michael (2001), The Five "Confucian" Classics, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-08185-5.

- Owen, Stephen (1996). An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03823-8.

- Riegel, Jeffrey (2001). "Shih-ching Poetry and Didacticism in Ancient Chinese Literature". In Mair, Victor H. (ed.). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 97–109. ISBN 0-231-10984-9.

- Saussy, Haun (1993), The Problem of a Chinese Aesthetic, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2593-4.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007), ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- Shi, Zhongwen; Hu, Xiaowen (2011), "The History of Literature in the Warring States Period", The Whole History of China, China: China Books Publishing House, ISBN 9787506823623. 10 volumes.

- Smith, Adam; Poli, Maddalena (2021), "Establishing the text of the Odes: The Anhui University Bamboo Manuscript", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 84 (3): 515–557, doi:10.1017/S0041977X22000015.

- Yip, Wai-lim (1997), Chinese Poetry: An Anthology of Major Modes and Genres, Durham and London: Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0-8223-1946-7.

- Wang, C. H. (1975), "Towards Defining a Chinese Heroism", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 95 (1): 25–35, doi:10.2307/599155, JSTOR 599155.

External links

[edit]- Bilingual Chinese-English searchable edition at Chinese Text Project

- Shi Ji Zhuan from the Chinese Text Initiative, University of Virginia: Chinese text based on Zhu Xi's edition; English translation from James Legge, with Chinese names updated to pinyin.

- The Book of Odes at Wengu zhixin. Chinese text with James Legge and Marcel Granet (partial) translations.

- Legge translation of the Book of Odes at the Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- Shijing and collated commentaries (Harrison Huang's website) Archived 2020-01-16 at the Wayback Machine (Chinese text)

- The Book of Songs at Chinese Notes; Chinese and English parallel text with matching dictionary entries.

Classic of Poetry

View on GrokipediaNomenclature

Alternative Names and Designations

The primary Chinese designation for the anthology is Shījīng (詩經), where shī (詩) denotes poetry or songs, and jīng (經) signifies a canonical classic or warp thread in the Confucian textual tradition.[8][9] Prior to the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), it was commonly referred to simply as Shī (詩), meaning "Poetry," or as the "300 Poems," reflecting its approximate count of 305 works gathered from oral folk traditions and courtly compositions during the Zhou period (c. 1046–256 BCE).[10] During the Han era, under imperial standardization and Confucian elevation, the suffix jīng was appended, marking its transformation from a collection of regional songs to one of the Five Classics (Wǔjīng), essential for bureaucratic examinations and moral instruction.[8][10] Alternative designations derive from its tripartite structure: Fēng (風, Airs of the States), Yǎ (雅, Odes of the Courts), and Sòng (頌, Hymns of the Temples), sometimes collectively termed Fēng Yǎ Sòng (風雅頌) to evoke its folk, aristocratic, and ritual elements.[8] A prominent variant is Máoshī (毛詩), referencing the Mao family's scholarly transmission, which became the dominant recension after Han Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BCE) endorsed it over rival versions like those of Lu and Qi.[8] This naming underscores transmission lineages rather than uniform authorship, with archaeological evidence from sites like Mawangdui (c. 168 BCE) confirming textual variants predating standardized editions.[3] In Western scholarship, English renderings vary, including "Book of Songs," "Book of Odes," and "Book of Poetry," with "Classic of Poetry" gaining prominence for aligning with the Han jīng connotation of authoritative scripture.[4] Romanization systems influence accessibility: modern Pinyin yields Shījīng, while older Wade-Giles uses Shih-ching, affecting phonetic fidelity in non-specialist contexts.[5] These translations shape perceptions, as "Songs" highlights empirical origins in Zhou-era folk recitations for rituals and governance, whereas "Classic" emphasizes later Han-era interpretive layers, potentially overshadowing its pre-canonical diversity as evidenced by oracle bone and bronze inscriptions.[5][3]Historical Context

Zhou Dynasty Setting

The Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–771 BCE) established a feudal system after overthrowing the Shang, wherein the king enfeoffed relatives, allies, and meritorious officials with hereditary lands organized into semi-autonomous states, creating a decentralized hierarchy bound by obligations of military service, tribute, and counsel. This structure positioned the Zhou king as the paramount lord under the Mandate of Heaven, a concept asserting divine sanction for rule contingent on moral governance and just order, with bronze inscriptions frequently recording land allotments, rank promotions, and vows of loyalty that reinforced these ties of fealty and reciprocal duty. Agrarian life formed the economic foundation, supported by bronze tools and early iron implements that boosted productivity in millet and wheat cultivation across the Yellow River basin, while ritual cycles of sacrifices and seasonal labors underscored the interdependence of human society and natural rhythms.)[11][12][13][14] In 771 BCE, nomadic incursions led by the Quanrong sacked the western capital at Haojing, killing King You and prompting the relocation of the royal court eastward to Luoyang, inaugurating the Eastern Zhou (771–256 BCE) amid weakened central authority. Early Eastern Zhou, encompassing the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BCE), witnessed accelerating fragmentation as regional lords asserted dominance, forming alliances and engaging in conflicts that undermined the original feudal compact, with royal influence reduced to ceremonial oversight. Bronze inscriptions from this transitional era continued to invoke hierarchical duties and ancestral precedents, yet reflected growing tensions in maintaining loyalty amid power shifts./04%3A_The_Development_of_States_-(800_BCE__300_BCE)/4.03%3A_Eastern_Zhou(771_BCE__400_BCE))[15][14] The dynasty's sociopolitical framework causally fostered an ethos of hierarchical obligation and cosmic harmony, as the king's legitimacy derived from exemplifying virtue to secure heavenly favor, with lapses inviting disorder manifest in famines or invasions—a realism echoed in inscriptions linking official diligence to state prosperity and ancestral merit. This emphasis on duty-bound loyalty within a natural order of superiors and inferiors provided the cultural substrate for expressions of governance ideals, distinct from later egalitarian constructs, grounded in the empirical record of ritual bronzes and land charters that prioritized stability through fealty over individual autonomy.[16][13][17]Estimated Composition Dates

The poems comprising the Classic of Poetry (Shijing) are estimated to have been composed primarily between the 11th and 7th centuries BCE, with linguistic archaisms and historical allusions providing the strongest empirical anchors for this range rather than later Han dynasty attributions to Confucius or earlier legendary figures. Archaeological evidence, such as oracle bone inscriptions and early bronze vessel texts from the Western Zhou (c. 1046–771 BCE), corroborates the antiquity of ritual language echoed in the hymns, while phonetic reconstructions of Old Chinese forms in the poems align with dated inscriptions, rejecting unsubstantiated extensions into the 5th century BCE or later based on the absence of post-600 BCE linguistic innovations or historical mismatches. Manuscripts on bamboo slips, including those from the Shanghai Museum dated paleographically to the mid-Warring States period (c. 4th–3rd centuries BCE), preserve near-canonical versions of select poems, indicating an oral-to-written stabilization by the late Western Zhou or early Eastern Zhou but confirming the core corpus predates these copies by centuries through consistent archaic vocabulary and syntax not found in contemporaneous texts.[18] Stratification by the traditional divisions reveals temporal layering: the Song (Hymns) of Lu, Shang, and Zhou, totaling 40 poems, exhibit the most archaic features, including ritual formulae paralleling Western Zhou bronze inscriptions (c. 11th–9th centuries BCE), positioning them as the earliest stratum tied to dynastic foundational cults. The Ya (Odes), divided into Da ya (Greater Odes) and Xiao ya (Lesser Odes), span Western Zhou courtly compositions—evident in Da ya's references to early kings like Wen and Wu—with Xiao ya extending into early Eastern Zhou (c. 8th–7th centuries BCE) via allusions to political upheavals post-771 BCE relocation of the capital. In contrast, the Guo feng (Airs of the States), 160 folk-style poems from 15 regions, cluster toward the later end (c. 8th–7th centuries BCE), as their dialectal variations and social motifs align with Eastern Zhou fragmentation, though linguistic conservatism precludes dating beyond 600 BCE. This internal differentiation, derived from comparative philology rather than Mao school commentaries, underscores a gradual accretion from elite ritual origins to broader societal expressions, with no verifiable additions after the Spring and Autumn period's onset.[19][20]Compilation and Organization

Traditional Compilation Narratives

The primary traditional narrative credits Confucius (551–479 BCE) with compiling the Classic of Poetry by selecting and editing 305 poems from an original corpus of around 3,000 odes, reportedly excising those deemed excessively licentious or morally deficient to align with ethical instruction.[8] This account, preserved in Han dynasty historiography, portrays the process as a deliberate curation for pedagogical purposes, drawing on the master's reputed use of poetry to inculcate virtue, as referenced in the Analects. However, no contemporary records from the fifth century BCE substantiate the claim, rendering it a retrospective attribution that elevates the anthology's authority within emerging Confucian orthodoxy rather than a verifiable historical event.[21] A complementary tradition traces the poems' origins to Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE) practices, wherein royal music officials, dispatched quarterly to feudal states, gathered folk airs (feng), courtly songs (ya), and hymns (song) to reflect public sentiment and inform governance—a mechanism described in ritual compendia like the Zhouli, which details the yueguan (music master's) role in archiving such materials for state rituals and political diagnostics.[8] These collections, purportedly maintained in the king's music bureau, supplied the raw material later refined into the anthology, underscoring a causal link between Zhou bureaucratic oversight and the preservation of oral traditions. Yet the Zhouli itself, compiled during the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), idealizes rather than documents contemporaneous operations, introducing skepticism regarding the scale and systematic nature of such efforts absent archaeological confirmation. Empirical assessment reveals no pre-Han artifacts evincing the full 305-poem compilation; while discrete verses surface in Warring States philosophical works like the Xunzi and Mozi (c. fourth to third centuries BCE), indicating circulation of individual pieces, the standardized corpus and its tripartite division materialize prominently in early Han exegeses.[19] This evidentiary gap suggests the narratives primarily served to canonize the text, embedding it in a framework of moral realism where poetry functions as empirical testimony to societal virtues and vices, thereby justifying its scriptural status over precise reconstructive history.[8]Divisions and Poem Counts

The Classic of Poetry (Shijing) is organized into four principal divisions: Guo Feng (Airs of the States), Xiao Ya (Minor Odes), Da Ya (Major Odes), and Song (Hymns), totaling 305 poems in the standard Mao edition transmitted since the Han dynasty.[8][1] This structure reflects a progression from regional folk traditions to courtly and ritual compositions, aligning with Zhou hierarchical cosmology by starting with local state airs, advancing to dynastic odes of varying scope, and culminating in ancestral praises.[8][5]| Division | Description | Number of Poems |

|---|---|---|

| Guo Feng | Airs from 15 feudal states | 160 |

| Xiao Ya | Minor court odes | 74 |

| Da Ya | Major court odes | 31 |

| Song | Hymns and praises | 40 |