Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tibia

View on Wikipedia| Tibia | |

|---|---|

Position of tibia (shown in red) | |

Cross section of the leg showing the different compartments (latin terminology) | |

| Details | |

| Articulations | Knee, ankle, superior and inferior tibiofibular joint |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | (os) tibia |

| MeSH | D013977 |

| TA98 | A02.5.06.001 |

| TA2 | 1397 |

| FMA | 24476 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The tibia (/ˈtɪbiə/; pl.: tibiae /ˈtɪbii/ or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects the knee with the ankle. The tibia is found on the medial side of the leg next to the fibula and closer to the median plane. The tibia is connected to the fibula by the interosseous membrane of leg, forming a type of fibrous joint called a syndesmosis with very little movement. The tibia is named for the flute tibia. It is the second largest bone in the human body, after the femur. The leg bones are the strongest long bones as they support the rest of the body.

Structure

[edit]In human anatomy, the tibia is the second largest bone after the femur. As in other vertebrates the tibia is one of two bones in the lower leg, the other being the fibula, and is a component of the knee and ankle joints. The tibia together with the fibula make up the front part of the leg, between the knee and the ankle, known as the shin.

The ossification or formation of the bone starts from three centers, one in the shaft and one in each extremity.

The tibia is categorized as a long bone and is as such composed of a diaphysis and two epiphyses. The diaphysis is the midsection of the tibia, also known as the shaft or body. While the epiphyses are the two rounded extremities of the bone; an upper (also known as superior or proximal) closest to the thigh and a lower (also known as inferior or distal) closest to the foot. The tibia is most contracted in the lower third and the distal extremity is smaller than the proximal.

Upper extremity

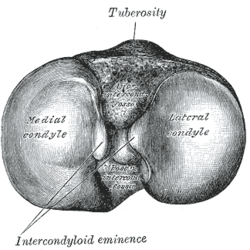

[edit]Condyles of tibia

[edit]

The proximal or upper extremity of the tibia is expanded in the transverse plane with a medial and lateral condyle, which are both flattened in the horizontal plane. The medial condyle is the larger of the two and is better supported over the shaft. The upper surfaces of the condyles articulate with the femur to form the tibiofemoral joint, the weightbearing part of the knee joint.[1]

The medial and lateral condyle are separated by the intercondylar area, where the cruciate ligaments and the menisci attach. Here the medial and lateral intercondylar tubercle forms the intercondylar eminence. Together with the medial and lateral condyle the intercondylar region forms the tibial plateau, which both articulates with and is anchored to the lower extremity of the femur. The intercondylar eminence divides the intercondylar area into an anterior and posterior part. The anterolateral region of the anterior intercondylar area are perforated by numerous small openings for nutrient arteries.[1]

The articular surfaces of both condyles are concave, particularly centrally. The flatter outer margins are in contact with the menisci. The medial condyles superior surface is oval in form and extends laterally onto the side of medial intercondylar tubercle. The lateral condyles superior surface is more circular in form and its medial edge extends onto the side of the lateral intercondylar tubercle. The posterior surface of the medial condyle bears a horizontal groove for part of the attachment of the semimembranosus muscle, whereas the lateral condyle has a circular facet for articulation with the head of the fibula.[1]

Beneath the condyles is the tibial tuberosity which serves for attachment of the patellar ligament, a continuation of the quadriceps femoris muscle.[1]

Facets

[edit]The superior articular surface presents two smooth articular facets.

- The medial facet, oval in shape, is slightly concave from side to side, and from before backward.

- The lateral, nearly circular, is concave from side to side, but slightly convex from before backward, especially at its posterior part, where it is prolonged on to the posterior surface for a short distance.

The central portions of these facets articulate with the condyles of the femur, while their peripheral portions support the menisci of the knee joint, which here intervene between the two bones.

Intercondyloid eminence

[edit]Between the articular facets in the intercondylar area, but nearer the posterior than the anterior aspect of the bone, is the intercondyloid eminence (spine of tibia), surmounted on either side by a prominent tubercle, on to the sides of which the articular facets are prolonged; in front of and behind the intercondyloid eminence are rough depressions for the attachment of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments and the menisci.

Surfaces

[edit]The anterior surfaces of the condyles are continuous with one another, forming a large somewhat flattened area; this area is triangular, broad above, and perforated by large vascular foramina; narrow below where it ends in a large oblong elevation, the tuberosity of the tibia, which gives attachment to the patellar ligament; a bursa intervenes between the deep surface of the ligament and the part of the bone immediately above the tuberosity.

Posteriorly, the condyles are separated from each other by a shallow depression, the posterior intercondyloid fossa, which gives attachment to part of the posterior cruciate ligament of the knee-joint. The medial condyle presents posteriorly a deep transverse groove, for the insertion of the tendon of the semimembranosus.

Its medial surface is convex, rough, and prominent; it gives attachment to the medial collateral ligament.

The lateral condyle presents posteriorly a flat articular facet, nearly circular in form, directed downward, backward, and lateralward, for articulation with the head of the fibula. Its lateral surface is convex, rough, and prominent in front: on it is an eminence, situated on a level with the upper border of the tuberosity and at the junction of its anterior and lateral surfaces, for the attachment of the iliotibial band. Just below this a part of the extensor digitorum longus takes origin and a slip from the tendon of the biceps femoris is inserted.

Shaft

[edit]

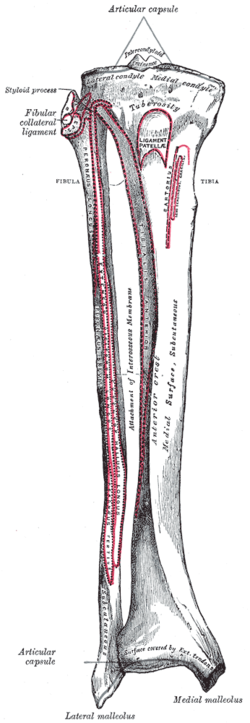

The shaft or body of the tibia is triangular in cross-section and forms three borders: an anterior, medial, and lateral or interosseous border. These three borders form three surfaces: the medial, lateral, and posterior.[2]

Borders

[edit]The anterior crest or border, the most prominent of the three, commences above at the tuberosity, and ends below at the anterior margin of the medial malleolus. It is sinuous and prominent in the upper two-thirds of its extent, but smooth and rounded below; it gives attachment to the deep fascia of the leg.

The medial border is smooth and rounded above and below, but more prominent in the center. It begins at the back part of the medial condyle, and ends at the posterior border of the medial malleolus; its upper part gives attachment to the tibial collateral ligament of the knee-joint to the extent of about 5 cm., and insertion to some fibers of the popliteus muscle. From its middle third some fibers of the soleus and flexor digitorum longus muscles take origin.

The interosseous crest or lateral border is thin and prominent, especially its central part, and gives attachment to the interosseous membrane; it commences above in front of the fibular articular facet, and bifurcates below, to form the boundaries of a triangular rough surface, for the attachment of the interosseous ligament connecting the tibia and fibula.

Surfaces

[edit]The medial surface is smooth, convex, and broader above than below; its upper third, directed forward and medialward, is covered by the aponeurosis derived from the tendon of the sartorius, and by the tendons of the Gracilis and Semitendinosus, all of which are inserted nearly as far forward as the anterior crest; in the rest of its extent it is subcutaneous.

The lateral surface is narrower than the medial; its upper two-thirds present a shallow groove for the origin of the Tibialis anterior; its lower third is smooth, convex, curves gradually forward to the anterior aspect of the bone, and is covered by the tendons of the Tibialis anterior, Extensor hallucis longus, and Extensor digitorum longus, arranged in this order from the medial side.

The posterior surface presents, at its upper part, a prominent ridge, the popliteal line, which extends obliquely downward from the back part of the articular facet for the fibula to the medial border, at the junction of its upper and middle thirds; it marks the lower limit of the insertion of the Popliteus, serves for the attachment of the fascia covering this muscle, and gives origin to part of the Soleus, Flexor digitorum longus, and Tibialis posterior. The triangular area, above this line, gives insertion to the Popliteus. The middle third of the posterior surface is divided by a vertical ridge into two parts; the ridge begins at the popliteal line and is well-marked above, but indistinct below; the medial and broader portion gives origin to the Flexor digitorum longus, the lateral and narrower to part of the Tibialis posterior. The remaining part of the posterior surface is smooth and covered by the Tibialis posterior, Flexor digitorum longus, and Flexor hallucis longus. Immediately below the popliteal line is the nutrient foramen, which is large and directed obliquely downward.

Lower extremity

[edit]

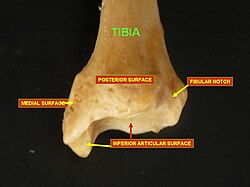

The distal end of the tibia is much smaller than the proximal end and presents five surfaces; it is prolonged downward on its medial side as a strong pyramidal process, the medial malleolus. The lower extremity of the tibia together with the fibula and talus forms the ankle joint.

Surfaces

[edit]The inferior articular surface is quadrilateral, and smooth for articulation with the talus. It is concave from before backward, broader in front than behind, and traversed from before backward by a slight elevation, separating two depressions. It is continuous with that on the medial malleolus.

The anterior surface of the lower extremity is smooth and rounded above, and covered by the tendons of the Extensor muscles; its lower margin presents a rough transverse depression for the attachment of the articular capsule of the ankle-joint.

The posterior surface is traversed by a shallow groove directed obliquely downward and medialward, continuous with a similar groove on the posterior surface of the talus and serving for the passage of the tendon of the Flexor hallucis longus.

The lateral surface presents a triangular rough depression for the attachment of the inferior interosseous ligament connecting it with the fibula; the lower part of this depression is smooth, covered with cartilage in the fresh state, and articulates with the fibula. The surface is bounded by two prominent borders (the anterior and posterior colliculi), continuous above with the interosseous crest; they afford attachment to the anterior and posterior ligaments of the lateral malleolus.

The medial surface – see medial malleolus for details.

Fractures

[edit]Ankle fractures of the tibia have several classification systems based on location or mechanism:

- Medial malleolus – Herscovici classification

- Posterior malleolus – Haruguchi classification

- Mechanism – Lauge-Hansen classification

Blood supply

[edit]The tibia is supplied with blood from two sources: A nutrient artery, as the main source, and periosteal vessels derived from the anterior tibial artery.[3]

Joints

[edit]The tibia is a part of four joints; the knee, ankle, superior and inferior tibiofibular joint.

In the knee the tibia forms one of the two articulations with the femur, often referred to as the tibiofemoral components of the knee joint.;[4][5] it is the weightbearing part of the knee joint.[2] The tibiofibular joints are the articulations between the tibia and fibula which allows very little movement.[citation needed] The proximal tibiofibular joint is a small plane joint. The joint is formed between the undersurface of the lateral tibial condyle and the head of fibula. The joint capsule is reinforced by anterior and posterior ligament of the head of the fibula.[2] The distal tibiofibular joint (tibiofibular syndesmosis) is formed by the rough, convex surface of the medial side of the distal end of the fibula, and a rough concave surface on the lateral side of the tibia.[2]

The part of the ankle joint known as the talocrural joint, is a synovial hinge joint that connects the distal ends of the tibia and fibula in the lower limb with the proximal end of the talus. The articulation between the tibia and the talus bears more weight than between the smaller fibula and the talus.[citation needed]

Development

[edit]The tibia is ossified from three centers: a primary center for the diaphysis (shaft) and a secondary center for each epiphysis (extremity). Ossification begins in the center of the body, about the seventh week of fetal life, and gradually extends toward the extremities.

The center for the upper epiphysis appears before or shortly after birth at close to 34 weeks gestation; it is flattened in form, and has a thin tongue-shaped process in front, which forms the tuberosity; that for the lower epiphysis appears in the second year.

The lower epiphysis fuses with the tibial shaft at about the eighteenth, and the upper one fuses about the twentieth year.

Two additional centers occasionally exist, one for the tongue-shaped process of the upper epiphysis, which forms the tuberosity, and one for the medial malleolus.

Function

[edit]Muscle attachments

[edit]| Muscle | Direction | Attachment[6] |

| Tensor fasciae latae muscle | Insertion | Gerdy's tubercle |

| Quadriceps femoris muscle | Insertion | Tuberosity of the tibia |

| Sartorius muscle | Insertion | Pes anserinus |

| Gracilis muscle | Insertion | Pes anserinus |

| Semitendinosus muscle | Insertion | Pes anserinus |

| Horizontal head of the semimembranosus muscle | Insertion | Medial condyle |

| Popliteus muscle | Insertion | Posterior side of the tibia over the soleal line |

| Tibialis anterior muscle | Origin | Lateral side of the tibia |

| Extensor digitorum longus muscle | Origin | Lateral condyle |

| Soleus muscle | Origin | Posterior side of the tibia under the soleal line |

| Flexor digitorum longus muscle | Origin | Posterior side of the tibia under the soleal line |

Strength

[edit]The tibia has been modeled as taking an axial force during walking that is up to 4.7 bodyweight. Its bending moment in the sagittal plane in the late stance phase is up to 71.6 bodyweight times millimetre.[7]

Clinical significance

[edit]Fracture

[edit]Fractures of the tibia can be divided into those that only involve the tibia; bumper fracture, Segond fracture, Gosselin fracture, toddler's fracture, and those including both the tibia and fibula; trimalleolar fracture, bimalleolar fracture, Pott's fracture.

The tibial shaft is the most common location for stress fractures in athletes.[8]

Society and culture

[edit]In Judaism, the tibia, or shankbone, of a goat or sheep is used in the Passover Seder plate.

Other animals

[edit]The structure of the tibia in most other tetrapods is essentially similar to that in humans. The tuberosity of the tibia, a crest to which the patellar ligament attaches in mammals, is instead the point for the tendon of the quadriceps muscle in reptiles, birds, and amphibians, which have no patella.[9]

Additional images

[edit]-

Shape of right tibia

-

3D image

-

Longitudinal section of tibia showing interior

-

Right knee-joint. Anterior view.

-

Right knee joint from the front, showing interior ligaments

-

Left knee joint from behind, showing interior ligaments

-

Left talocrural joint

-

Coronal section through right talocrural and talocalcaneal joints

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection. Anterior view

-

Bones of the right leg. Anterior surface

-

Bones of the right leg. Posterior surface

-

Dorsum of Foot. Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Ankle joint. Deep dissection.

-

Tibia Anatomy

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 256 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 256 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b c d Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, A. Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M. (2010). Gray´s Anatomy for Students (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 558–560. ISBN 978-0-443-06952-9.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, A. Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M. (2010). Gray´s Anatomy for Students (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 584–588. ISBN 978-0-443-06952-9.

- ^ Nelson G, Kelly P, Peterson L, Janes J (1960). "Blood supply of the human tibia". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 42-A (4): 625–36. doi:10.2106/00004623-196042040-00007. PMID 13854090.

- ^ Rytter S, Egund N, Jensen LK, Bonde JP (2009). "Occupational kneeling and radiographic tibiofemoral and patellofemoral osteoarthritis". J Occup Med Toxicol. 4 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/1745-6673-4-19. PMC 2726153. PMID 19594940.

- ^ Gill TJ, Van de Velde SK, Wing DW, Oh LS, Hosseini A, Li G (December 2009). "Tibiofemoral and patellofemoral kinematics after reconstruction of an isolated posterior cruciate ligament injury: in vivo analysis during lunge". Am J Sports Med. 37 (12): 2377–85. doi:10.1177/0363546509341829. PMC 3832057. PMID 19726621.

- ^ Bojsen-Møller, Finn; Simonsen, Erik B.; Tranum-Jensen, Jørgen (2001). Bevægeapparatets anatomi [Anatomy of the Locomotive Apparatus] (in Danish) (12th ed.). Munksgaard Danmark. pp. 364–367. ISBN 978-87-628-0307-7.

- ^ Wehner, T; Claes, L; Simon, U (2009). "Internal loads in the human tibia during gait". Clin Biomech. 24 (3): 299–302. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.12.007. PMID 19185959.

- ^ McCormick, Frank; Nwachukwu, Benedict U.; Provencher, Matthew T. (2012). "Stress Fractures in Runners". Clinics in Sports Medicine. 31 (2): 291–306. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.09.012. Retrieved 2025-10-04.

tibial shaft is the most common location for stress fractures in athletes. ... Whereas high-risk stress fractures are so classified based on their tendency for incomplete healing or fracture completion...

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 205. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

Tibia

View on GrokipediaStructure

Proximal end

The proximal end of the tibia is expanded to form the tibial plateau, a broad, flat superior surface that participates in the knee joint. This region consists of two condyles: the medial condyle, which is larger and longer than the lateral condyle, and both of which have concave superior articular surfaces adapted for articulation with the femoral condyles.[3][5] The medial condyle measures approximately 5-6 cm in anteroposterior length on average in adults, while the lateral condyle is shorter at about 4-5 cm, contributing to the overall tibial plateau width of 7-8 cm mediolaterally.[6][7] Between the condyles lies the intercondylar eminence, a central ridge projecting upward from the tibial plateau, featuring medial and lateral tubercles that serve as attachment sites for the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments.[3][5] The eminence divides the plateau into medial and lateral facets, with the medial facet exhibiting a posterior slope angle of approximately 5-10 degrees and the lateral facet around 6-10 degrees relative to the tibial shaft axis, influencing load distribution across the knee.[8][9] On the anterior aspect, the tibial tuberosity forms a prominent, elongated projection extending inferiorly from the intercondylar region, providing the insertion point for the patellar ligament.[4][10] The posterior surface of the proximal tibia features the soleal line, an oblique ridge that runs inferomedially from near the fibular articular facet, marking the origin site for the soleus muscle.[3][11] This line divides the posterior surface into upper and lower regions, with the upper area also accommodating attachments for other proximal structures. Common variations include differences in ridge prominence.[3]Shaft

The shaft, or diaphysis, of the tibia exhibits a triangular cross-section that provides structural integrity for weight-bearing, featuring three principal borders: the anterior border, which is subcutaneous and palpable as the shin; the medial border, which is rounded and connects the anterior and posterior aspects; and the posterior border, which is less prominent and gives origin to muscular structures. Additionally, the lateral, or interosseous, border serves as the attachment site for the interosseous membrane linking the tibia to the fibula, facilitating load distribution between the two bones.[3][4] The tibial shaft possesses three corresponding surfaces adapted to its biomechanical role. The anteromedial surface is smooth and subcutaneous, lying close to the skin with minimal muscular coverage, which allows for direct palpation. The lateral surface faces the fibula and supports the interosseous membrane. The posterior surface is subdivided by the oblique soleal line—a ridge running inferomedially—into a superior medial area and an inferior lateral area, enhancing compartmentalization for soft tissue attachments.[3][4] A prominent nutrient foramen is typically present on the posterior surface of the tibial shaft, most often located below the soleal line and between it and the interosseous border, serving as the entry point for the primary nutrient artery to supply the medullary cavity. In approximately 98.6% of cases, a single foramen is observed, positioned at about the upper two-fifths of the shaft length. Variations may include multiple foramina in ~1.4% of cases.[3][12] Cortical thickness in the tibial diaphysis varies regionally to optimize resistance to mechanical loads, with the anterior cortex generally thicker than the posterior cortex—particularly in younger adults—to withstand bending and compressive forces during locomotion. This anterior-posterior disparity in thickness contributes to the bone's overall strength, with the anterior region often measuring significantly greater than the posterior in both sexes.[13] Under diaphyseal stress from repetitive loading, the tibial shaft undergoes subperiosteal bone remodeling, characterized by periosteal apposition of new bone tissue on the outer surface in response to mechanical stimuli, following principles of adaptive bone formation to enhance structural resilience. This process, governed by Wolff's law, involves deposition on the periosteal envelope to counter tensile stresses, while endosteal resorption may occur concurrently to maintain medullary space.[14] The shaft gradually tapers from the broader proximal end to the distal expansion, maintaining its cylindrical form for efficient axial load transmission.[4]Distal end

The distal end of the tibia flares slightly from the diaphysis to form specialized articular and malleolar features that support the ankle joint and facilitate weight transmission. The medial malleolus projects inferiorly as a pyramidal bony extension, measuring approximately 1.5 cm in height from the level of the tibial plafond to its tip on average. Its lateral surface bears a comma-shaped malleolar articular facet that articulates directly with the medial aspect of the talus, helping to form the medial wall of the ankle mortise.[15][3] The inferior surface of the distal tibia comprises medial and lateral articular areas that unite to create the tibial plafond, a broad, concave platform that receives the dome of the talus during ankle motion. This plafond has a mediolateral width of approximately 6-7 cm. Laterally, the distal tibia presents the fibular notch, a triangular concave facet on the posterolateral surface that accommodates the lateral malleolus of the fibula, establishing the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis essential for maintaining syndesmotic integrity.[16][3] On the posterior surface of the medial malleolus, two prominent colliculi—the larger medial colliculus and the smaller lateral colliculus—protrude as tubercles separated by a shallow groove. These colliculi provide primary attachment points for the superficial and deep components of the deltoid ligament, respectively, bolstering medial ankle stability without direct involvement in other ligamentous complexes. Variations in colliculi size may occur but are typically consistent.[17][4]Articulations and ligaments

Knee joint

The proximal tibia forms the tibial plateau, which consists of the medial and lateral tibial condyles that articulate with the corresponding condyles of the femur to create the tibiofemoral joint. This articulation is a modified hinge joint that allows for flexion, extension, and limited rotation. Interposed between the femoral and tibial condyles are the medial and lateral menisci, crescent-shaped fibrocartilaginous structures that deepen the articular surfaces of the tibia, enhance joint congruence, and serve as primary shock absorbers by distributing compressive forces and reducing friction during weight-bearing activities.[18][19] The intercondylar area of the tibia, located between the condyles, provides attachment sites for key stabilizing ligaments. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) originates from the anterior intercondylar area of the tibia, just lateral to the anterior tibial spine, and ascends to insert on the lateral femoral condyle, resisting anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur. The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) attaches to the posterior intercondylar area of the tibia and extends to the medial femoral condyle, preventing posterior tibial displacement. Additionally, the medial collateral ligament (MCL) originates from the medial epicondyle of the femur and inserts on the medial aspect of the proximal tibia just below the joint line, resisting valgus forces. The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) originates from the lateral epicondyle of the femur and inserts on the head of the fibula, resisting varus forces.[20][21][22][23] The tibial plateau typically exhibits a mild varus orientation of 3-10 degrees in adults, as measured by the medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA), which influences lower limb mechanical alignment by directing forces medially. This inherent varus tilt promotes efficient load transfer but can predispose to medial compartment overload if exaggerated, increasing the risk of osteoarthritis due to uneven stress distribution. In normal knees, the medial compartment bears approximately 50-60% of the total joint load during gait, with the menisci further modulating this by absorbing up to 50% of the compressive forces in that region.[24][25][26]Proximal tibiofibular joint

The proximal tibiofibular joint is a plane synovial joint formed by the articulation between the posterolateral aspect of the lateral tibial condyle and the medial aspect of the fibular head.[27] This joint is enclosed within a fibrous capsule lined by synovial membrane and covered with hyaline cartilage, allowing for minimal mobility while maintaining structural integrity.[27] In approximately 10% of individuals, the synovial cavity communicates with the knee joint, potentially influencing fluid dynamics and joint health.[28] The joint capsule is reinforced by several key ligaments, including the anterior and posterior proximal tibiofibular ligaments, which provide primary stability against separation and translation.[27] Additional reinforcement comes from the fibular collateral ligament, which attaches to the fibular head and helps resist varus forces, and the arcuate ligament complex, which contributes to posterolateral stability by anchoring the fibula to surrounding structures.00108-9/fulltext) These ligaments collectively limit excessive movement, ensuring the joint functions as a secondary stabilizer in the lower leg.[29] Motion at the proximal tibiofibular joint is limited to slight gliding, with translations typically ranging from 1 to 2 mm in anterior-posterior and medial-lateral directions, accommodating fibular rotation during lower limb movements.[27] The joint's orientation lies in a nearly horizontal plane, which facilitates this subtle mobility without compromising overall alignment.[29] This gliding motion supports rotational adjustments, such as external fibular rotation during ankle dorsiflexion.[27] Functionally, the joint plays a critical role in preventing excessive lateral displacement of the tibia relative to the fibula during knee flexion, thereby dissipating lateral bending moments and torsional stresses transmitted from the ankle.[27] It bears minimal compressive load—approximately one-sixth of the ankle's total—primarily functioning under tension to maintain tibiofibular alignment.[27] This stabilizing contribution integrates with broader knee mechanics to enhance overall lower limb stability during locomotion.[29]Distal tibiofibular joint

The distal tibiofibular joint, also known as the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis, is a fibrous syndesmotic articulation that binds the distal ends of the tibia and fibula, providing essential stability to the ankle complex.[30] This joint consists of the osseous components of the distal tibia and fibula connected by a robust interosseous membrane that extends distally to form the interosseous ligament, along with reinforcing ligaments that limit excessive motion.[31] The syndesmosis allows minimal physiological movement, primarily a slight widening of approximately 1 mm during normal gait or dorsiflexion to accommodate talar motion within the ankle mortise.[31] The primary stabilizing structures include the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL), which originates from the anterolateral distal tibia (Chaput's tubercle) and fans out in a trapezoidal, multifascicular configuration to insert on the anterior fibula (Wagstaffe's tubercle), spanning 6-21 mm in length.[30] The posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL), the strongest component, arises from the posterolateral distal tibia (Volkmann's tubercle) with a broad base that converges triangularly at an oblique angle of 20-40 degrees to attach on the posterior lateral malleolus.[30] The interosseous ligament serves as a distal extension of the interosseous membrane, forming a pyramidal network that further resists diastasis between the bones. The inferior transverse tibiofibular ligament, a strong band passing transversely behind the talus from the distal tibia to the fibula, provides additional posterior stability to the syndesmosis.[31] This syndesmosis plays a critical role in forming the lateral aspect of the ankle mortise, ensuring precise congruence for the talus and preventing excessive lateral translation or rotation under load; even a 1 mm increase in syndesmotic width can reduce tibiotalar contact area by up to 42%.[30] On imaging, the normal tibiofibular clear space measures less than 6 mm on anteroposterior and mortise views, serving as a key diagnostic parameter for integrity assessment.[31] The ligaments attach to specific distal tibial tubercles, including the lateral tibial notch, to anchor the syndesmosis securely.[30]Ankle joint

The tibiotalar joint, also known as the talocrural joint, is a synovial hinge joint formed by the articulation of the dome-shaped superior surface of the talus with the inferior articular surface of the distal tibia, known as the tibial plafond, which is embraced laterally by the medial and lateral malleoli to create a stable mortise structure.[32] The tibial plafond is concave in the sagittal plane and slightly convex transversely, precisely matching the convex trochlear surface of the talus to facilitate congruent contact and smooth gliding during motion.[33] This configuration ensures the talus remains securely positioned within the mortise, with the malleoli providing lateral and medial constraints to prevent excessive translation.[32] The deltoid ligament, a strong triangular complex on the medial aspect, originates from the apex and anterior and posterior colliculi of the medial malleolus of the tibia, fanning out to attach to the talus, calcaneus, and navicular bones, thereby reinforcing medial stability and resisting eversion forces at the ankle.[34] Its deep layer remains intra-articular, directly supporting the tibiotalar articulation, while the superficial layer provides broader reinforcement.[34] At the tibiotalar interface, primary movements include dorsiflexion, ranging from 10° to 20°, and plantarflexion, ranging from 40° to 50°, enabling essential sagittal plane motion for gait while the mortise limits transverse deviations.[35] During weight-bearing, load distribution across the joint favors the tibial side, with approximately 83% transmitted through the tibiotalar contact, of which about 40% passes via the medial malleolus to the talus.[33] The distal tibial features, including the plafond and medial malleolus, form the key components of this mortise, optimizing force transmission during locomotion.[32]Blood supply and innervation

Arterial supply

The arterial supply to the tibia derives from branches of the popliteal artery, which bifurcates into the anterior tibial artery—supplying the anterior surface—and the tibioperoneal trunk, from which the posterior tibial and peroneal arteries arise to perfuse the posterior and lateral aspects, respectively.[36] The nutrient artery, the primary vessel for the diaphysis, originates from the posterior tibial artery and enters the bone through a posterior foramen located in the middle third of the shaft, distal to the soleal line.[36][37] This artery penetrates the posterolateral cortex and traverses an oblique nutrient canal, averaging 5 cm in length, before reaching the medullary cavity, where it bifurcates into multiple ascending branches (typically three) and a single descending branch that distribute as medullary arteries to the endosteal surface.[36][38] These medullary branches further ramify into radial twigs that supply the Haversian systems within the cortex, forming endosteal capillary sinusoids essential for intraosseous circulation and bone nutrition.[38] The nutrient artery accounts for the dominant portion of diaphyseal blood flow, providing up to 91% of cortical perfusion in adults, with the inner two-thirds of the cortex relying almost entirely on this endosteal supply.[39] In contrast, the periosteal network supplies the outer third of the cortical bone and serves as a secondary source, particularly important for viability when the nutrient artery is compromised, such as in fractures.[39][37] This network arises from longitudinal and transverse branches of the anterior tibial artery along the anterior and anterolateral surfaces, reinforced by genicular branches (superior, middle, and inferior medial/lateral) from the popliteal artery around the proximal tibia, and malleolar branches from the anterior and posterior tibial arteries near the distal end.[36][40] The peroneal artery also contributes perforating branches to the posterolateral periosteum, forming anastomotic connections that enhance overall bone vascularity.[36]Venous drainage and innervation

The venous drainage of the tibia primarily occurs through the deep veins that accompany the anterior and posterior tibial arteries, which converge to form the popliteal vein in the popliteal fossa, facilitating return of blood from the lower leg to the systemic circulation.[41] These venae comitantes run parallel to their respective arteries, collecting deoxygenated blood from the periosteum, muscles, and bone marrow before uniting posteriorly at the knee.[42] Within the bone itself, medullary veins in the diaphyseal marrow drain into emissary channels that perforate the cortex, connecting to transcortical venules and the external venous network without a distinct central venous sinus.[43] This open circulatory system allows diffuse drainage across the medullary canal, extending from metaphysis to metaphysis, via cortical sinusoids, Haversian venules, and intersinusoidal shunts.[43] Emissary veins exit the bone through nutrient foramina, linking intraosseous drainage—similar in pathway to arterial nutrient entry points—to the surrounding soft tissue veins.[44] The tibia receives sensory innervation primarily from branches of the tibial nerve, which supplies the posterior and medial aspects of the lower leg, including the periosteum along the shaft and medial border.[45] The saphenous nerve, a terminal cutaneous branch of the tibial nerve, provides sensory fibers to the medial periosteum, particularly around the medial malleolus and ankle joint.[46] Laterally and posteriorly, the sural nerve—formed by contributions from both the tibial and common fibular nerves—innervates the periosteum of the lateral tibia and fibular articulation.[47] Intraosseous innervation includes nociceptors located in the endosteum lining the medullary cavity and within Haversian canals of the cortical bone, enabling detection of mechanical or inflammatory stimuli that contribute to referred pain patterns in tibial injuries.[48] Sympathetic fibers, often adrenergic or cholinergic, accompany vascular structures within the periosteum, marrow, and cortical bone to regulate vasomotor tone and blood flow distribution.[48]Function

Weight-bearing and locomotion

The tibia functions as the principal weight-bearing structure in the lower extremity, transmitting compressive forces generated during static posture and dynamic activities such as walking and running from the femur to the talus. Its robust diaphyseal structure and trabecular architecture at the ends enable it to endure substantial axial loads, with peak compressive forces reaching 6–14 times body weight during high-impact running, as evidenced by biomechanical analyses of peak ground reaction forces amplified by muscular contractions.[49] This capacity ensures stability and propulsion, minimizing deformation under repetitive cyclic loading inherent to locomotion. In terms of load distribution, the tibia transmits approximately 90% of the total axial force through the lower leg, while the fibula assumes only about 10%, primarily stabilizing the ankle laterally rather than sharing significant compressive responsibility.[50] This uneven partitioning arises from the tibia's medial positioning and broader articular surfaces, optimizing force transfer along the body's midline for efficient upright gait. The alignment facilitating this is further refined by tibial torsion, which measures 15–25 degrees of external rotation in adults relative to the proximal tibia, aligning the ankle joint axis with the transverse plane to promote a natural, energy-efficient stride without excessive varus or valgus deviations.[51] A key adaptation enhancing the tibia's role in locomotion is its intrinsic geometry, including a slight anterior bowing along the diaphysis, which aids shock absorption by allowing controlled elastic deformation and even dissipation of impact forces at heel strike, thereby reducing peak stresses on the bone and surrounding tissues.[52] The shaft's triangular cross-section and cortical thickening further bolster resistance to buckling under these eccentric loads. Biomechanically, the tibia's performance under compression is quantified by the stress equation , where denotes compressive stress, the applied force (such as multiples of body weight during gait), and the bone's cross-sectional area; this relationship underscores how variations in tibial morphology directly influence load tolerance and fatigue resistance during prolonged activity.[53]Muscle attachments and mechanics

The anterior surface of the tibia serves as a primary origin for muscles of the anterior compartment of the leg, facilitating dorsiflexion and inversion of the foot. The tibialis anterior muscle originates from the upper two-thirds of the lateral surface of the tibial shaft and the adjacent interosseous membrane, allowing it to act as the primary dorsiflexor and invertor of the foot at the ankle joint.[5] Additionally, the extensor digitorum longus originates from the proximal lateral surface near the fibula but includes attachments to the anterior aspect of the tibia, contributing to toe extension and assisting in dorsiflexion.[5] On the proximal end, the tibial tuberosity provides the insertion site for the patellar ligament, which transmits the force of the quadriceps femoris muscle group from the femur, enabling knee extension.[5] The posterior surface of the tibia supports origins for key muscles of the deep and superficial posterior compartments, promoting plantarflexion, inversion, and toe flexion essential for propulsion and stability. The tibialis posterior originates from the upper two-thirds of the posterior tibial surface, the interosseous membrane, and the adjacent fibula, serving as the primary invertor of the foot and a supporter of the medial longitudinal arch.[54] The soleus muscle arises from the soleal line—a prominent ridge on the upper three-quarters of the posterior tibial shaft—and the posterior fibula head, acting as a powerful plantarflexor that works synergistically with the gastrocnemius during gait.[5] The flexor digitorum longus originates from the medial two-thirds of the posterior tibial surface below the soleal line, facilitating flexion of the lateral four toes and contributing to foot inversion.[5] Collectively, these attachments along the posterior tibia and soleal line enable balanced force application for lower limb propulsion. These muscle attachments generate critical torques and force vectors that underpin lower limb mechanics, particularly in inversion/eversion and knee stability. The tibialis posterior, through its leverage on the posterior tibia, produces substantial inversion torque at the subtalar and transverse tarsal joints, supporting a normal physiological range of foot inversion of approximately 20 degrees.[55] Similarly, the tibialis anterior attachment on the lateral tibia contributes to inversion alongside dorsiflexion, countering eversion forces from peroneal muscles on the fibula to maintain frontal plane stability. The quadriceps force transmitted via the patellar ligament to the tibial tuberosity creates an anterior shear vector on the proximal tibia relative to the femur, with peak shear occurring near full knee extension (0-20 degrees of flexion) due to the alignment of the insertion angle.[56] This shear is counteracted by posterior structures, highlighting the flexor-extensor balance: anterior extensions from the quadriceps are opposed by posterior flexions from hamstring insertions at the pes anserinus on the medial proximal tibia (sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus), ensuring dynamic knee stability and preventing excessive anterior tibial translation during weight transfer.[5]Clinical significance

Fractures and injuries

Tibial fractures represent a significant portion of lower extremity injuries, often resulting from high-energy trauma such as motor vehicle accidents or falls, as well as low-energy mechanisms in osteoporotic bone. These fractures can occur at the proximal, diaphyseal, or distal regions of the tibia, with classifications guiding treatment based on fracture pattern, displacement, and associated soft tissue damage. Proximal tibial fractures, particularly those involving the tibial plateau, are intra-articular and commonly classified using the Schatzker system, which delineates six types based on the location and morphology of the injury. Type I involves a lateral split fracture without depression, typically from valgus force; type II combines a split with central depression of the lateral plateau, often seen in older patients with weaker bone; types III through VI progress to more complex bicondylar or medial involvement with increasing comminution and energy.[57] Shaft fractures of the tibia, comprising the diaphysis, are among the most common long bone fractures and are categorized by pattern, including transverse (from direct impact), oblique, or spiral (from torsional forces). Open tibial shaft fractures, which expose bone to the environment, are further graded by the Gustilo-Anderson classification to assess soft tissue involvement: type I features a clean wound less than 1 cm with minimal periosteal stripping; type II involves a wound 1-10 cm with moderate contamination but no extensive soft tissue loss; type III is severe, subdivided into IIIA (adequate soft tissue coverage despite high contamination), IIIB (periosteal stripping with tissue loss requiring flap coverage), and IIIC (vascular injury necessitating repair).[58][59] Distal tibial fractures include pilon fractures, which affect the weight-bearing articular surface and result from axial loading, leading to high-energy comminution and metaphyseal involvement, often with significant soft tissue compromise. Malleolar fractures at the distal tibia, involving the medial malleolus or affecting syndesmotic stability, are classified by the Danis-Weber system based on the level of the associated fibular fracture: type A (infrasyndesmotic, below the syndesmosis, typically stable); type B (trans-syndesmotic, at the level of the syndesmosis, with potential instability); and type C (suprasyndesmotic, above the syndesmosis, often disrupting the syndesmosis and requiring fixation).[60][61] The annual incidence of tibial fractures varies by region and subtype, with tibial shaft fractures occurring at approximately 16.9 per 100,000 population, while overall tibia fractures reach up to 51.7 per 100,000, showing higher rates in males, athletes due to sports-related trauma, and elderly individuals from falls on osteoporotic bone.[62][63] Common complications of tibial fractures include acute compartment syndrome, characterized by intracompartmental pressures exceeding 30 mmHg or a delta pressure (diastolic blood pressure minus compartment pressure) less than 30 mmHg, which can lead to muscle necrosis if not urgently decompressed via fasciotomy. Non-union rates for tibial fractures range from 5-10%, influenced by factors such as open wounds, infection, and poor vascularity, with higher risks in distal and segmental patterns.[64][65]Other conditions and surgical considerations

Osteomyelitis of the tibia is a serious bacterial infection primarily caused by Staphylococcus aureus, leading to bone necrosis and sequestrum formation, where a segment of dead bone becomes separated from viable tissue.[66] This condition often presents with prolonged sinus tracts, pus drainage, and radiographic evidence of osteosclerosis alongside dead space formation, necessitating aggressive debridement and antibiotic therapy.[67] Vascular supply risks exacerbate the infection's spread, potentially compromising surrounding soft tissues if not addressed promptly.[68] Osteoporosis contributes to tibial stress fractures through reduced bone density, defined by a T-score of -2.5 or lower on dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, increasing susceptibility in the lower extremities, particularly with varus malalignment.[69] These insufficiency fractures, distinct from acute trauma, arise from repetitive loading on weakened trabecular and cortical bone, often in the medial tibial plateau or shaft, and may mimic other overuse injuries.[70] Medial tibial stress syndrome, commonly known as shin splints, involves periosteal inflammation along the posteromedial border of the tibia due to repetitive traction from surrounding muscles like the tibialis posterior.[71] This overuse condition typically affects runners and athletes, presenting as diffuse pain exacerbated by activity, and is thought to stem from microtrauma to the periosteum rather than true stress fractures.[72] Osgood-Schlatter disease is an apophysitis of the tibial tuberosity caused by repetitive traction from the patellar tendon on the developing ossification center. It predominantly affects adolescents during growth spurts, presenting with anterior knee pain, swelling, and tenderness at the tibial tuberosity, often aggravated by physical activity. The condition is generally self-limiting and managed conservatively with rest and activity modification.[73] Blount disease, also known as tibia vara, is a developmental growth disorder of the medial proximal tibial physis, resulting in progressive varus deformity and leg bowing in children. It has infantile and adolescent forms, with associated risk factors including obesity and mechanical stress on the knee. Treatment options range from bracing in mild cases to surgical osteotomy for correction in advanced cases.[74] Paget's disease of bone is a chronic disorder of abnormal bone remodeling, which can affect the tibia leading to bone enlargement, deformity (such as bowing), pain, secondary osteoarthritis, and increased risk of pathological fractures. Treatment typically involves bisphosphonates to suppress excessive bone turnover and manage symptoms.[75] Surgical interventions for tibial pathologies include intramedullary nailing for shaft involvement, where reamed techniques may offer advantages such as lower nonunion rates and fewer reoperations compared to unreamed methods, particularly in closed fractures, without significantly increasing complications.[76][77] For tibial plateau disruptions, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) using locking compression plates restores articular congruence and supports early mobilization, with low-profile mini-fragment plates (2.0-2.7 mm) aiding in fragment-specific stabilization.[78][79] Recent advances in tibial reconstruction incorporate 3D-printed custom implants, such as porous titanium alloy prostheses for intercalary defects, which promote osseointegration and improve functional outcomes in post-resection cases like tumors or infections, as demonstrated in studies since 2020.[80] These patient-specific designs, often with highly cancellous surfaces, enhance bone and soft tissue integration while reducing mechanical complications in complex reconstructions.[81]Development and variations

Embryonic development and ossification

The development of the tibia begins during the embryonic period through endochondral ossification, where mesenchymal cells in the lower limb bud condense to form a cartilaginous template. Mesenchymal condensation occurs around the sixth week of gestation, followed by chondrification by the seventh week, establishing the basic structure of the future bone.[82][83] The primary ossification center emerges in the diaphysis (shaft) of the tibia at approximately 6-7 weeks of fetal life, where vascular invasion into the calcified cartilage matrix allows osteoblasts to deposit bone tissue, gradually replacing the cartilage from the center outward. Secondary ossification centers form later in the epiphyses: the proximal epiphysis center appears around birth, while the distal epiphysis center develops at about 6-12 months postpartum.[5][82] Throughout childhood and adolescence, longitudinal growth continues at the epiphyseal plates (physes), zones of cartilage between the epiphyses and diaphysis that undergo endochondral ossification. This process involves chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophy, followed by matrix calcification, apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes, and vascular invasion that brings osteoprogenitor cells to form new bone trabeculae. The proximal physis typically closes between 16 and 18 years of age, while the distal physis fuses earlier, around 14-16 years, marking skeletal maturity.[82][84][5] Hormonal factors significantly influence this progression, with growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) stimulating chondrocyte proliferation and overall longitudinal growth at the physes. Estrogen, rising during puberty, accelerates senescence of the growth plate by promoting rapid ossification and fusion of the epiphyses to the diaphysis, effectively halting further elongation.[85][86][87]Anatomical variations

Anatomical variations in the tibia encompass deviations from the typical straight morphology, including differences in alignment, presence of accessory structures, rotational angles, bilateral symmetry, and population-specific traits. These variations can influence biomechanics and clinical assessments but are often asymptomatic in the general population. Bowing variations of the tibia include genu varum, characterized by lateral deviation of the mechanical axis with varus angulation exceeding normal adult alignment of 3-5 degrees of valgus, and recurvatum, involving hyperextension of the knee joint. In newborns, a physiologic varus angulation of 15-20 degrees is common and typically corrects to neutral by age 2, but persistent bowing beyond this may reflect individual variation or underlying conditions.[88] Accessory ossicles near the tibial malleolus, such as os subtibiale at the medial aspect, occur with a prevalence of 0.7-1.2% in the general population and may mimic fractures on imaging. These small, corticated structures, typically 4-15 mm in size, arise from unfused ossification centers or avulsion fragments and are usually incidental findings without symptoms.[89] Tibial torsion, the rotational alignment relative to the proximal tibia, normally measures 24-30 degrees of external torsion in adults; excessive external torsion exceeding 30 degrees is associated with altered patellofemoral joint loading, increased lateral patellar tilt, and higher risk of instability or pain. This variation can contribute to dynamic valgus during gait and may necessitate derotational osteotomy if symptomatic.[90] Bilateral asymmetry in tibial length is prevalent in approximately 44% of individuals, with typical differences ranging from 0.1 to 0.8 mm, though larger discrepancies up to 3 mm or more occur in subsets of the population and may affect lower limb alignment. Such asymmetry is more common on the right side and does not usually impact function unless exceeding 5 mm.[91][92] Ethnic differences include longer tibial lengths in individuals of African descent compared to those of European descent, with tibiae in individuals of African descent being significantly longer and narrower overall, potentially influencing relative proportions to the femur and locomotion patterns. These variations highlight the need for population-specific reference data in orthopedic planning.[93]Comparative anatomy

In mammals

In quadrupedal mammals adapted for cursorial locomotion, such as horses, the tibia is elongated to enhance stride length and speed. The fibula is rudimentary and partially fused to the tibia distally, forming the lateral malleolus, which reduces weight while maintaining structural integrity for high-speed running.[94] This fusion is a common adaptation in large cursorial quadrupeds, optimizing energy efficiency during sustained locomotion.[95] Among primates, tibial morphology reflects locomotor diversity, with bipedal humans exhibiting increased robusticity in the diaphysis and proximal epiphysis compared to arboreal non-human primates like monkeys, whose tibiae show greater curvature to facilitate climbing and suspension.[96] This robusticity in humans supports upright weight-bearing and shock absorption during terrestrial bipedalism, contrasting with the more gracile, mediolaterally compressed tibiae of arboreal forms that prioritize flexibility over compressive strength.[97] In carnivorous mammals, particularly felids, the tibia is shortened relative to body size but markedly robust, enabling powerful explosive movements like pouncing on prey. This morphology, with reinforced cortical bone along the shaft, withstands high torsional and bending forces during ambush predation. Across cursorial mammals, the tibia typically bears most of the compressive load in the crus during locomotion, with the fibula providing supplementary stabilization but minimal weight support. In canines, the caudal aspect of the tibia serves as an attachment site for the deep digital flexor muscle, facilitating digit flexion essential for traction and grip during agile movement.[98]In non-mammalian vertebrates

In reptiles, the tibia typically remains a distinct bone from the fibula, though they are of comparable length and articulate proximally with the femur via separate condyles, supporting the sprawling gait characteristic of many species such as lizards.[99] The tibia is often stouter than the fibula, with an expanded proximal head that articulates broadly with the femoral condyle, facilitating lateral limb movement during terrestrial locomotion.[100] In some reptiles, including certain squamates, the tibia and fibula exhibit close association or partial fusion distally, enhancing structural stability for sprawling postures. For instance, in the fossil crocodilian Simosuchus clarki, the tibia and fibula are associated with approximately 20 dermal bony plates (osteoderms), providing armor-like protection along the limb.[101] In birds, the homologue of the tibia is the tibiotarsus, formed by the fusion of the tibia with the proximal tarsal bones (astragalus and calcaneum), which creates a robust, elongated structure essential for weight-bearing during bipedal locomotion and flight support. This fusion occurs early in development, resulting in a single bone with a cnemial tubercle for muscle attachment and a fibular crest where the reduced fibula articulates.[102] In many avian species, particularly larger flying birds, the tibiotarsus is pneumatic, containing air sacs that reduce weight while maintaining strength for aerial efficiency.[103] Among amphibians, the tibia in anurans such as frogs is fused with the fibula to form a single tibiofibula bone, which is shorter relative to the femur and adapted for powerful jumping propulsion rather than sustained walking.[104] This fusion is complete in adults, with the tibiofibula presenting expanded, flattened ends for articulation and persistent cartilaginous elements in some distal regions that aid in flexibility during leaps.[105] In more basal amphibians like salamanders, the tibia and fibula remain separate but are slender and elongated, supporting undulating aquatic or terrestrial movement. Evolutionarily, the tibia traces its origins to the endochondral elements of sarcopterygian fish pelvic fins, where multiple radials contributed to the proximal limb skeleton; in early tetrapods, this led to a reduction in fibular dominance as the tibia became the primary load-bearing bone in the crus.[106] This trend reflects adaptations for terrestrial support, with the fibula diminishing in size and function across tetrapod lineages, contrasting with the more prominent tibial role in derived forms like mammals.[107]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Osteology_of_the_Reptiles/Chapter_5