Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

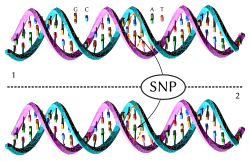

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

View on Wikipedia

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP /snɪp/; plural SNPs /snɪps/) is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in a sufficiently large fraction of the population (e.g. 1% or more),[1] many publications[2][3][4] do not apply such a frequency threshold.

For example, a G nucleotide present at a specific location in a reference genome may be replaced by an A in a minority of individuals. The two possible nucleotide variations of this SNP – G or A – are called alleles.[5]

SNPs can help explain differences in susceptibility to a wide range of diseases across a population. For example, a common SNP in the CFH gene is associated with increased risk of age-related macular degeneration.[6] Differences in the severity of an illness or response to treatments may also be manifestations of genetic variations caused by SNPs. For example, two common SNPs in the APOE gene, rs429358 and rs7412, lead to three major APO-E alleles with different associated risks for development of Alzheimer's disease and age at onset of the disease.[7]

Single nucleotide substitutions with an allele frequency of less than 1% are sometimes called single-nucleotide variants.[8] "Variant" may also be used as a general term for any single nucleotide change in a DNA sequence,[9] encompassing both common SNPs and rare mutations, whether germline or somatic.[10][11] The term single-nucleotide variant has therefore been used to refer to point mutations found in cancer cells.[12] DNA variants must also commonly be taken into consideration in molecular diagnostics applications such as designing PCR primers to detect viruses, in which the viral RNA or DNA sample may contain single-nucleotide variants.[13] However, this nomenclature uses arbitrary distinctions (such as an allele frequency of 1%) and is not used consistently across all fields; the resulting disagreement has prompted calls for a more consistent framework for naming differences in DNA sequences between two samples.[14][15]

Types

[edit]

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms may fall within coding sequences of genes, non-coding regions of genes, or in the intergenic regions (regions between genes). SNPs within a coding sequence do not necessarily change the amino acid sequence of the protein that is produced, due to degeneracy of the genetic code.[16]

SNPs in the coding region are of two types: synonymous SNPs and nonsynonymous SNPs. Synonymous SNPs do not affect the protein sequence, while nonsynonymous SNPs change the amino acid sequence of protein.[17]

- SNPs in non-coding regions can manifest in a higher risk of cancer,[18] and may affect mRNA structure and disease susceptibility.[19] Non-coding SNPs can also alter the level of expression of a gene, as an eQTL (expression quantitative trait locus).

- SNPs in coding regions:

- synonymous substitutions by definition do not result in a change of amino acid in the protein, but still can affect its function in other ways. An example would be a seemingly silent mutation in the multidrug resistance gene 1 (MDR1), which codes for a cellular membrane pump that expels drugs from the cell, can slow down translation and allow the peptide chain to fold into an unusual conformation, causing the mutant pump to be less functional (in MDR1 protein e.g. C1236T polymorphism changes a GGC codon to GGT at amino acid position 412 of the polypeptide (both encode glycine) and the C3435T polymorphism changes ATC to ATT at position 1145 (both encode isoleucine)).[20]

- nonsynonymous substitutions:

- missense – single change in the base results in change in amino acid of protein and its malfunction which leads to disease (e.g. c.1580G>T SNP in LMNA gene – position 1580 (nt) in the DNA sequence (CGT codon) causing the guanine to be replaced with the thymine, yielding CTT codon in the DNA sequence, results at the protein level in the replacement of the arginine by the leucine in the position 527,[21] at the phenotype level this manifests in overlapping mandibuloacral dysplasia and progeria syndrome)

- nonsense – point mutation in a sequence of DNA that results in a premature stop codon, or a nonsense codon in the transcribed mRNA, and in a truncated, incomplete, and usually nonfunctional protein product (e.g. Cystic fibrosis caused by the G542X mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene).[22]

SNPs that are not in protein-coding regions may still affect gene splicing, transcription factor binding, messenger RNA degradation, or the sequence of noncoding RNA. Gene expression affected by this type of SNP is referred to as an eSNP (expression SNP) and may be upstream or downstream from the gene.

Frequency

[edit]More than 600 million SNPs have been identified across the human genome in the world's population.[23] A typical genome differs from the reference human genome at 4–5 million sites, most of which (more than 99.9%) consist of SNPs and short indels.[24]

Within a genome

[edit]The genomic distribution of SNPs is not homogenous; SNPs occur in non-coding regions more frequently than in coding regions or, in general, where natural selection is acting and "fixing" the allele (eliminating other variants) of the SNP that constitutes the most favorable genetic adaptation.[25] Other factors, like genetic recombination and mutation rate, can also determine SNP density.[26]

SNP density can be predicted by the presence of microsatellites: AT microsatellites in particular are potent predictors of SNP density, with long (AT)(n) repeat tracts tending to be found in regions of significantly reduced SNP density and low GC content.[27]

Within a population

[edit]Since there are variations between human populations, a SNP allele that is common in one geographical or ethnic group may be rarer in another. However, this pattern of variation is relatively rare; in a global sample of 67.3 million SNPs, the Human Genome Diversity Project "found no such private variants that are fixed in a given continent or major region. The highest frequencies are reached by a few tens of variants present at >70% (and a few thousands at >50%) in Africa, the Americas, and Oceania. By contrast, the highest frequency variants private to Europe, East Asia, the Middle East, or Central and South Asia reach just 10 to 30%."[28]

Within a population, SNPs can be assigned a minor allele frequency (MAF)—the lowest allele frequency at a locus that is observed in a particular population.[29] This is simply the lesser of the two allele frequencies for single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

With this knowledge, scientists have developed new methods in analyzing population structures in less studied species.[30][31][32] By using pooling techniques, the cost of the analysis is significantly lowered.[33] These techniques are based on sequencing a population in a pooled sample instead of sequencing every individual within the population by itself. With new bioinformatics tools, there is a possibility of investigating population structure, gene flow, and gene migration by observing the allele frequencies within the entire population. With these protocols there is a possibility for combining the advantages of SNPs with micro satellite markers.[34][35] However, there is information lost in the process, such as linkage disequilibrium and zygosity information.

Applications

[edit]Single nucleotide polymorphisms serve as powerful molecular markers in contemporary genetic research and clinical practice. Association studies, particularly genome-wide association studies (GWAS), represent the primary application of SNP technology for identifying genetic variants linked to human diseases and traits.[36] These comprehensive analyses examine hundreds of thousands of genetic markers simultaneously to detect statistical associations between specific SNPs and phenotypic characteristics, enabling researchers to uncover genetic contributions to complex disorders including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neurological conditions.[37]

The development of tag SNP methodology has significantly enhanced the efficiency of genomic studies by exploiting patterns of linkage disequilibrium across the human genome. Tag SNPs function as representative markers that capture genetic variation within specific chromosomal regions, allowing researchers to survey large genomic areas without genotyping every individual variant.[38] This approach reduces both the financial cost and computational burden of large-scale genetic studies while maintaining sufficient power to detect disease-associated loci. The selection of optimal tag SNPs relies on sophisticated algorithms that identify markers capable of capturing the maximum amount of genetic information within defined genomic intervals.[39]

Haplotype reconstruction represents another fundamental application where SNPs enable the characterization of inherited genetic blocks. Researchers utilize dense SNP maps to identify and analyze haplotype structures, which consist of sets of closely linked alleles that tend to be transmitted together through generations.[40] These haplotype patterns provide insights into population history, demographic events, and evolutionary processes that have shaped contemporary genetic diversity. The International HapMap Project exemplified this application by creating comprehensive maps of common haplotype patterns across diverse human populations.[41]

Linkage disequilibrium analysis forms the theoretical foundation for many SNP-based applications in population genetics and disease mapping. This phenomenon describes the non-random association of alleles at different genomic positions, which occurs when variants are inherited together more frequently than would be expected by chance alone.[42] The extent of linkage disequilibrium between SNPs depends primarily on physical distance along chromosomes and local recombination rates, with closer variants generally showing stronger associations. Understanding these patterns enables researchers to predict which SNPs will provide redundant information and guides the selection of informative markers for association studies.[43]

In genetic epidemiology, SNPs have emerged as essential tools for investigating disease transmission patterns and population structure. Whole-genome sequencing approaches utilize SNP variation to define transmission clusters in infectious disease outbreaks, where cases showing similar genetic profiles may represent linked transmission events.[44] This application has proven particularly valuable for tuberculosis surveillance and contact tracing, where traditional epidemiological methods may fail to identify all transmission links. Additionally, SNP-based analyses contribute to understanding population stratification and ancestry, which are crucial factors in designing appropriate study controls and interpreting association results across diverse ethnic groups.[45]

Importance

[edit]Variations in the DNA sequences of humans can affect how humans develop diseases and respond to pathogens, chemicals, drugs, vaccines, and other agents. SNPs are also critical for personalized medicine.[46] Examples include biomedical research, forensics, pharmacogenetics, and disease causation, as outlined below.

Clinical research

[edit]Genome-wide association study (GWAS)

[edit]One of the main contributions of SNPs in clinical research is genome-wide association study (GWAS).[47] Genome-wide genetic data can be generated by multiple technologies, including SNP array and whole genome sequencing. GWAS has been commonly used in identifying SNPs associated with diseases or clinical phenotypes or traits. Since GWAS is a genome-wide assessment, a large sample site is required to obtain sufficient statistical power to detect all possible associations. Some SNPs have relatively small effect on diseases or clinical phenotypes or traits. To estimate study power, the genetic model for disease needs to be considered, such as dominant, recessive, or additive effects. Due to genetic heterogeneity, GWAS analysis must be adjusted for race.

Candidate gene association study

[edit]Candidate gene association study is commonly used in genetic study before the invention of high throughput genotyping or sequencing technologies.[48] Candidate gene association study is to investigate limited number of pre-specified SNPs for association with diseases or clinical phenotypes or traits. So this is a hypothesis driven approach. Since only a limited number of SNPs are tested, a relatively small sample size is sufficient to detect the association. Candidate gene association approach is also commonly used to confirm findings from GWAS in independent samples.

Homozygosity mapping in disease

[edit]Genome-wide SNP data can be used for homozygosity mapping.[49] Homozygosity mapping is a method used to identify homozygous autosomal recessive loci, which can be a powerful tool to map genomic regions or genes that are involved in disease pathogenesis.

Methylation patterns

[edit]

Recently, preliminary results reported SNPs as important components of the epigenetic program in organisms.[50][51] Moreover, cosmopolitan studies in European and South Asiatic populations have revealed the influence of SNPs in the methylation of specific CpG sites.[52] In addition, meQTL enrichment analysis using GWAS database, demonstrated that those associations are important toward the prediction of biological traits.[52][53][54]

Forensic sciences

[edit]SNPs have historically been used to match a forensic DNA sample to a suspect but has been made obsolete due to advancing STR-based DNA fingerprinting techniques. However, the development of next-generation-sequencing (NGS) technology may allow for more opportunities for the use of SNPs in phenotypic clues such as ethnicity, hair color, and eye color with a good probability of a match. This can additionally be applied to increase the accuracy of facial reconstructions by providing information that may otherwise be unknown, and this information can be used to help identify suspects even without a STR DNA profile match.

Some cons to using SNPs versus STRs is that SNPs yield less information than STRs, and therefore more SNPs are needed for analysis before a profile of a suspect is able to be created. Additionally, SNPs heavily rely on the presence of a database for comparative analysis of samples. However, in instances with degraded or small volume samples, SNP techniques are an excellent alternative to STR methods. SNPs (as opposed to STRs) have an abundance of potential markers, can be fully automated, and a possible reduction of required fragment length to less than 100 bp.[27]

Pharmacogenetics

[edit]Pharmacogenetics focuses on identifying genetic variations including SNPs associated with differential responses to treatment.[55] Many drug metabolizing enzymes, drug targets, or target pathways can be influenced by SNPs. The SNPs involved in drug metabolizing enzyme activities can change drug pharmacokinetics, while the SNPs involved in drug target or its pathway can change drug pharmacodynamics. Therefore, SNPs are potential genetic markers that can be used to predict drug exposure or effectiveness of the treatment. Genome-wide pharmacogenetic study is called pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics are important in the development of precision medicine, especially for life-threatening diseases such as cancers.

Disease

[edit]Only small amount of SNPs in the human genome may have impact on human diseases. Large scale GWAS has been done for the most important human diseases, including heart diseases, metabolic diseases, autoimmune diseases, and neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders.[47] Most of the SNPs with relatively large effects on these diseases have been identified. These findings have significantly improved understanding of disease pathogenesis and molecular pathways, and facilitated development of better treatment. Further GWAS with larger samples size will reveal the SNPs with relatively small effect on diseases. For common and complex diseases, such as type-2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and Alzheimer's disease, multiple genetic factors are involved in disease etiology. In addition, gene-gene interaction and gene-environment interaction also play an important role in disease initiation and progression.[56]

Examples

[edit]- rs6311 and rs6313 are SNPs in the Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor gene on human chromosome 13.[57]

- The SNP − 3279C/A (rs3761548) is amongst the SNPs locating in the promoter region of the Foxp3 gene, might be involved in cancer progression.[58]

- A SNP in the F5 gene causes Factor V Leiden thrombophilia.[59]

- rs3091244 is an example of a triallelic SNP in the CRP gene on human chromosome 1.[60]

- TAS2R38 codes for PTC tasting ability, and contains 6 annotated SNPs.[61]

- rs148649884 and rs138055828 in the FCN1 gene encoding M-ficolin crippled the ligand-binding capability of the recombinant M-ficolin.[62]

- rs12821256 on a cis-regulatory module changes the amount of transcription of the KIT ligand gene. Among northern Europeans, high levels of transcription leads to brown hair, and low levels leads to blond hair. This is an example of overt but non-pathological phenotype change by one SNP.[63]

- An intronic SNP in DNA mismatch repair gene PMS2 (rs1059060, Ser775Asn) is associated with increased sperm DNA damage and risk of male infertility.[64]

Databases

[edit]As there are for genes, bioinformatics databases exist for SNPs.

- dbSNP is a SNP database from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). As of June 8, 2015[update], dbSNP listed 149,735,377 SNPs in humans.[65][66]

- Kaviar[67] is a compendium of SNPs from multiple data sources including dbSNP.

- SNPedia is a wiki-style database supporting personal genome annotation, interpretation and analysis.

- The OMIM database describes the association between polymorphisms and diseases (e.g., gives diseases in text form)

- dbSAP – single amino-acid polymorphism database for protein variation detection[68]

- The Human Gene Mutation Database provides gene mutations causing or associated with human inherited diseases and functional SNPs

- The International HapMap Project, where researchers are identifying Tag SNPs to be able to determine the collection of haplotypes present in each subject.

- GWAS Central allows users to visually interrogate the actual summary-level association data in one or more genome-wide association studies.

The International SNP Map working group mapped the sequence flanking each SNP by alignment to the genomic sequence of large-insert clones in Genebank. These alignments were converted to chromosomal coordinates that is shown in Table 1.[69] This list has greatly increased since, with, for instance, the Kaviar database now listing 162 million single nucleotide variants.

| Chromosome | Length(bp) | All SNPs | TSC SNPs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total SNPs | kb per SNP | Total SNPs | kb per SNP | ||

| 1 | 214,066,000 | 129,931 | 1.65 | 75,166 | 2.85 |

| 2 | 222,889,000 | 103,664 | 2.15 | 76,985 | 2.90 |

| 3 | 186,938,000 | 93,140 | 2.01 | 63,669 | 2.94 |

| 4 | 169,035,000 | 84,426 | 2.00 | 65,719 | 2.57 |

| 5 | 170,954,000 | 117,882 | 1.45 | 63,545 | 2.69 |

| 6 | 165,022,000 | 96,317 | 1.71 | 53,797 | 3.07 |

| 7 | 149,414,000 | 71,752 | 2.08 | 42,327 | 3.53 |

| 8 | 125,148,000 | 57,834 | 2.16 | 42,653 | 2.93 |

| 9 | 107,440,000 | 62,013 | 1.73 | 43,020 | 2.50 |

| 10 | 127,894,000 | 61,298 | 2.09 | 42,466 | 3.01 |

| 11 | 129,193,000 | 84,663 | 1.53 | 47,621 | 2.71 |

| 12 | 125,198,000 | 59,245 | 2.11 | 38,136 | 3.28 |

| 13 | 93,711,000 | 53,093 | 1.77 | 35,745 | 2.62 |

| 14 | 89,344,000 | 44,112 | 2.03 | 29,746 | 3.00 |

| 15 | 73,467,000 | 37,814 | 1.94 | 26,524 | 2.77 |

| 16 | 74,037,000 | 38,735 | 1.91 | 23,328 | 3.17 |

| 17 | 73,367,000 | 34,621 | 2.12 | 19,396 | 3.78 |

| 18 | 73,078,000 | 45,135 | 1.62 | 27,028 | 2.70 |

| 19 | 56,044,000 | 25,676 | 2.18 | 11,185 | 5.01 |

| 20 | 63,317,000 | 29,478 | 2.15 | 17,051 | 3.71 |

| 21 | 33,824,000 | 20,916 | 1.62 | 9,103 | 3.72 |

| 22 | 33,786,000 | 28,410 | 1.19 | 11,056 | 3.06 |

| X | 131,245,000 | 34,842 | 3.77 | 20,400 | 6.43 |

| Y | 21,753,000 | 4,193 | 5.19 | 1,784 | 12.19 |

| RefSeq | 15,696,674 | 14,534 | 1.08 | ||

| Totals | 2,710,164,000 | 1,419,190 | 1.91 | 887,450 | 3.05 |

Nomenclature

[edit]The nomenclature for SNPs include several variations for an individual SNP, while lacking a common consensus.

The rs### standard is that which has been adopted by dbSNP and uses the prefix "rs", for "reference SNP", followed by a unique and arbitrary number.[70] SNPs are frequently referred to by their dbSNP rs number, as in the examples above.

The Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) uses a standard which conveys more information about the SNP. Examples are:

- c.76A>T: "c." for coding region, followed by a number for the position of the nucleotide, followed by a one-letter abbreviation for the nucleotide (A, C, G, T, or U), followed by a greater than sign (">") to indicate substitution, followed by the abbreviation of the nucleotide which replaces the former[71][72][73]

- p.Ser123Arg: "p." for protein, followed by a three-letter abbreviation for the amino acid, followed by a number for the position of the amino acid, followed by the abbreviation of the amino acid which replaces the former.[74]

SNP analysis

[edit]SNPs can be easily assayed due to only containing two possible alleles and three possible genotypes involving the two alleles: homozygous A, homozygous B and heterozygous AB, leading to many possible techniques for analysis. Some include: DNA sequencing; capillary electrophoresis; mass spectrometry; single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP); single base extension; electrochemical analysis; denaturating HPLC and gel electrophoresis; restriction fragment length polymorphism; and hybridization analysis.

Programs for prediction of SNP effects

[edit]An important group of SNPs are those that corresponds to missense mutations causing amino acid change on protein level. Point mutation of particular residue can have different effect on protein function (from no effect to complete disruption its function). Usually, change in amino acids with similar size and physico-chemical properties (e.g. substitution from leucine to valine) has mild effect, and opposite. Similarly, if SNP disrupts secondary structure elements (e.g. substitution to proline in alpha helix region) such mutation usually may affect whole protein structure and function. Using those simple and many other machine learning derived rules a group of programs for the prediction of SNP effect was developed:[75]

- SIFT This program provides insight into how a laboratory induced missense or nonsynonymous mutation will affect protein function based on physical properties of the amino acid and sequence homology.

- LIST (Local Identity and Shared Taxa)[76][77] estimates the potential deleteriousness of mutations resulted from altering their protein functions. It is based on the assumption that variations observed in closely related species are more significant when assessing conservation compared to those in distantly related species.

- SNAP2

- SuSPect

- PolyPhen-2

- PredictSNP

- MutationTaster: official website

- Variant Effect Predictor from the Ensembl project

- SNPViz Archived 2020-08-07 at the Wayback Machine:[78] This program provides a 3D representation of the protein affected, highlighting the amino acid change so doctors can determine pathogenicity of the mutant protein.

- PROVEAN

- PhyreRisk is a database which maps variants to experimental and predicted protein structures.[79]

- Missense3D is a tool which provides a stereochemical report on the effect of missense variants on protein structure.[80]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "single-nucleotide polymorphism / SNP | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-10. Retrieved 2015-11-13.

- ^ Sherry, S. T.; Ward, M.; Sirotkin, K. (1999). "dbSNP—Database for Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Other Classes of Minor Genetic Variation". Genome Research. 9 (8): 677–679. doi:10.1101/gr.9.8.677. PMID 10447503. S2CID 10775908.

- ^ Lander, E. S.; et al. (2001). "Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome". Nature. 409 (6822): 860–921. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..860L. doi:10.1038/35057062. hdl:2027.42/62798. PMID 11237011.

- ^ Auton, Adam; et al. (2015). "A global reference for human genetic variation". Nature. 526 (7571): 68–74. Bibcode:2015Natur.526...68T. doi:10.1038/nature15393. PMC 4750478. PMID 26432245.

- ^ Monga, Isha; Qureshi, Abid; Thakur, Nishant; Gupta, Amit Kumar; Kumar, Manoj (September 2017). "ASPsiRNA: A Resource of ASP-siRNAs Having Therapeutic Potential for Human Genetic Disorders and Algorithm for Prediction of Their Inhibitory Efficacy". G3. 7 (9): 2931–2943. doi:10.1534/g3.117.044024. PMC 5592921. PMID 28696921.

- ^ Calippe, Bertrand; Guillonneau, Xavier; Sennlaub, Florian (March 2014). "Complement factor H and related proteins in age-related macular degeneration". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 337 (3): 178–184. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2013.12.003. ISSN 1631-0691. PMID 24702844.

- ^ Husain, Mohammed Amir; Laurent, Benoit; Plourde, Mélanie (2021-02-17). "APOE and Alzheimer's Disease: From Lipid Transport to Physiopathology and Therapeutics". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 15 630502. doi:10.3389/fnins.2021.630502. ISSN 1662-453X. PMC 7925634. PMID 33679311.

- ^ "Definition of single nucleotide variant - NCI Dictionary of Genetics Terms". www.cancer.gov. 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

- ^ Wright, Alan F (September 23, 2005), "Genetic Variation: Polymorphisms and Mutations", eLS, Wiley, doi:10.1038/npg.els.0005005, ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6, S2CID 82415195

- ^ Goya, R.; Sun, M. G.; Morin, R. D.; Leung, G.; Ha, G.; Wiegand, K. C.; Senz, J.; Crisan, A.; Marra, M. A.; Hirst, M.; Huntsman, D.; Murphy, K. P.; Aparicio, S.; Shah, S. P. (2010). "SNVMix: predicting single nucleotide variants from next-generation sequencing of tumors". Bioinformatics. 26 (6): 730–736. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq040. PMC 2832826. PMID 20130035.

- ^ Katsonis, Panagiotis; Koire, Amanda; Wilson, Stephen Joseph; Hsu, Teng-Kuei; Lua, Rhonald C.; Wilkins, Angela Dawn; Lichtarge, Olivier (2014-10-20). "Single nucleotide variations: Biological impact and theoretical interpretation". Protein Science. 23 (12): 1650–1666. doi:10.1002/pro.2552. ISSN 0961-8368. PMC 4253807. PMID 25234433.

- ^ Khurana, Ekta; Fu, Yao; Chakravarty, Dimple; Demichelis, Francesca; Rubin, Mark A.; Gerstein, Mark (2016-01-19). "Role of non-coding sequence variants in cancer". Nature Reviews Genetics. 17 (2): 93–108. doi:10.1038/nrg.2015.17. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 26781813. S2CID 14433306.

- ^ Dong, Hongjie; Wang, Shuai; Zhang, Junmei; Zhang, Kundi; Zhang, Fengyu; Wang, Hongwei; Xie, Shiling; Hu, Wei; Gu, Lichuan (2021). "Structure-Based Primer Design Minimizes the Risk of PCR Failure Caused by SARS-CoV-2 Mutations". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 11 741147. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.741147. ISSN 2235-2988. PMC 8573093. PMID 34760717.

- ^ Karki, Roshan; Pandya, Deep; Elston, Robert C.; Ferlini, Cristiano (July 15, 2015). "Defining "mutation" and "polymorphism" in the era of personal genomics". BMC Medical Genomics. 8 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 37. doi:10.1186/s12920-015-0115-z. ISSN 1755-8794. PMC 4502642. PMID 26173390.

- ^ Li, Heng (March 15, 2021). "SNP vs SNV". Heng Li's blog. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ Spencer, Paige S.; Barral, José M. (2012). "Genetic code redundancy and its influence on the encoded polypeptides". Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 1 e201204006. doi:10.5936/csbj.201204006. ISSN 2001-0370. PMC 3962081. PMID 24688635.

- ^ Chu, Duan; Wei, Lai (2019-04-16). "Nonsynonymous, synonymous and nonsense mutations in human cancer-related genes undergo stronger purifying selections than expectation". BMC Cancer. 19 (1): 359. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5572-x. ISSN 1471-2407. PMC 6469204. PMID 30991970.

- ^ Li G, Pan T, Guo D, Li LC (2014). "Regulatory Variants and Disease: The E-Cadherin -160C/A SNP as an Example". Molecular Biology International. 2014 967565. doi:10.1155/2014/967565. PMC 4167656. PMID 25276428.

- ^ Lu YF, Mauger DM, Goldstein DB, Urban TJ, Weeks KM, Bradrick SS (November 2015). "IFNL3 mRNA structure is remodeled by a functional non-coding polymorphism associated with hepatitis C virus clearance". Scientific Reports. 5 16037. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516037L. doi:10.1038/srep16037. PMC 4631997. PMID 26531896.

- ^ Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW, Sauna ZE, Calcagno AM, Ambudkar SV, Gottesman MM (January 2007). "A "silent" polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity". Science. 315 (5811): 525–8. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..525K. doi:10.1126/science.1135308. PMID 17185560. S2CID 15146955.

- ^ Al-Haggar M, Madej-Pilarczyk A, Kozlowski L, Bujnicki JM, Yahia S, Abdel-Hadi D, Shams A, Ahmad N, Hamed S, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M (November 2012). "A novel homozygous p.Arg527Leu LMNA mutation in two unrelated Egyptian families causes overlapping mandibuloacral dysplasia and progeria syndrome". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (11): 1134–40. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.77. PMC 3476705. PMID 22549407.

- ^ Cordovado SK, Hendrix M, Greene CN, Mochal S, Earley MC, Farrell PM, Kharrazi M, Hannon WH, Mueller PW (February 2012). "CFTR mutation analysis and haplotype associations in CF patients". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 105 (2): 249–54. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.10.013. PMC 3551260. PMID 22137130.

- ^ "What are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)?: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ^ Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, Abecasis GR (October 2015). "A global reference for human genetic variation". Nature. 526 (7571): 68–74. Bibcode:2015Natur.526...68T. doi:10.1038/nature15393. PMC 4750478. PMID 26432245.

- ^ Barreiro LB, Laval G, Quach H, Patin E, Quintana-Murci L (March 2008). "Natural selection has driven population differentiation in modern humans". Nature Genetics. 40 (3): 340–5. doi:10.1038/ng.78. PMID 18246066. S2CID 205357396.

- ^ Nachman MW (September 2001). "Single nucleotide polymorphisms and recombination rate in humans". Trends in Genetics. 17 (9): 481–5. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02409-X. PMID 11525814.

- ^ a b Varela MA, Amos W (March 2010). "Heterogeneous distribution of SNPs in the human genome: microsatellites as predictors of nucleotide diversity and divergence". Genomics. 95 (3): 151–9. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2009.12.003. PMID 20026267.

- ^ Bergström A, McCarthy SA, Hui R, Almarri MA, Ayub Q, Danecek P; et al. (2020). "Insights into human genetic variation and population history from 929 diverse genomes". Science. 367 (6484) eaay5012. doi:10.1126/science.aay5012. PMC 7115999. PMID 32193295.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhu Z, Yuan D, Luo D, Lu X, Huang S (2015-07-24). "Enrichment of Minor Alleles of Common SNPs and Improved Risk Prediction for Parkinson's Disease". PLOS ONE. 10 (7) e0133421. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1033421Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133421. PMC 4514478. PMID 26207627.

- ^ Hivert, Valentin; Leblois, Raphaël; Petit, Eric J.; Gautier, Mathieu; Vitalis, Renaud (2018-07-30). "Measuring Genetic Differentiation from Pool-seq Data". Genetics. 210 (1): 315–330. doi:10.1534/genetics.118.300900. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 6116966. PMID 30061425.

- ^ Ekblom, R; Galindo, J (2010-12-08). "Applications of next generation sequencing in molecular ecology of non-model organisms". Heredity. 107 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1038/hdy.2010.152. ISSN 0018-067X. PMC 3186121. PMID 21139633.

- ^ Ellegren, Hans (January 2014). "Genome sequencing and population genomics in non-model organisms". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 29 (1): 51–63. Bibcode:2014TEcoE..29...51E. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2013.09.008. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 24139972.

- ^ Chen, Chao; Parejo, Melanie; Momeni, Jamal; Langa, Jorge; Nielsen, Rasmus O.; Shi, Wei; Smartbees Wp Diversity Contributors, null; Vingborg, Rikke; Kryger, Per; Bouga, Maria; Estonba, Andone; Meixner, Marina (2022-01-21). "Population Structure and Diversity in European Honey Bees (Apismellifera L.)-An Empirical Comparison of Pool and Individual Whole-Genome Sequencing". Genes. 13 (2): 182. doi:10.3390/genes13020182. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 8872436. PMID 35205227.

{{cite journal}}:|last7=has generic name (help) - ^ Dorant, Yann; Benestan, Laura; Rougemont, Quentin; Normandeau, Eric; Boyle, Brian; Rochette, Rémy; Bernatchez, Louis (2019). "Comparing Pool-seq, Rapture, and GBS genotyping for inferring weak population structure: The American lobster (Homarus americanus) as a case study". Ecology and Evolution. 9 (11): 6606–6623. Bibcode:2019EcoEv...9.6606D. doi:10.1002/ece3.5240. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 6580275. PMID 31236247.

- ^ Vendrami, David L. J.; Telesca, Luca; Weigand, Hannah; Weiss, Martina; Fawcett, Katie; Lehman, Katrin; Clark, M. S.; Leese, Florian; McMinn, Carrie; Moore, Heather; Hoffman, Joseph I. (2017). "RAD sequencing resolves fine-scale population structure in a benthic invertebrate: implications for understanding phenotypic plasticity". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (2) 160548. Bibcode:2017RSOS....460548V. doi:10.1098/rsos.160548. PMC 5367306. PMID 28386419.

- ^ Uffelmann, Emil; Huang, Qin Qin; Munung, Nchangwi Syntia; de Vries, Jantina; Okada, Yukinori; Martin, Alicia R.; Martin, Hilary C.; Lappalainen, Tuuli; Posthuma, Danielle (2021-08-26). "Genome-wide association studies". Nature Reviews Methods Primers. 1 (1): 59. doi:10.1038/s43586-021-00056-9. ISSN 2662-8449.

- ^ Buniello, Annalisa; MacArthur, Jacqueline A. L.; Cerezo, Maria; Harris, Laura W.; Hayhurst, James; Malangone, Cinzia; McMahon, Aoife; Morales, Joannella; Mountjoy, Edward; Sollis, Elliot; Suveges, Daniel; Vrousgou, Olga; Whetzel, Patricia L.; Amode, Ridwan; Guillen, Jose A. (2019-01-08). "The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019". Nucleic Acids Research. 47 (D1): D1005 – D1012. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1120. ISSN 1362-4962. PMC 6323933. PMID 30445434.

- ^ Carlson, Christopher S.; Eberle, Michael A.; Rieder, Mark J.; Yi, Qian; Kruglyak, Leonid; Nickerson, Deborah A. (January 2004). "Selecting a maximally informative set of single-nucleotide polymorphisms for association analyses using linkage disequilibrium". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (1): 106–120. doi:10.1086/381000. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1181897. PMID 14681826.

- ^ Sebastiani, Paola; Lazarus, Ross; Weiss, Scott T.; Kunkel, Louis M.; Kohane, Isaac S.; Ramoni, Marco F. (2003-08-19). "Minimal haplotype tagging". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (17): 9900–9905. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.9900S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1633613100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 187880. PMID 12900503.

- ^ Gabriel, Stacey B.; Schaffner, Stephen F.; Nguyen, Huy; Moore, Jamie M.; Roy, Jessica; Blumenstiel, Brendan; Higgins, John; DeFelice, Matthew; Lochner, Amy; Faggart, Maura; Liu-Cordero, Shau Neen; Rotimi, Charles; Adeyemo, Adebowale; Cooper, Richard; Ward, Ryk (2002-06-21). "The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome". Science. 296 (5576): 2225–2229. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.2225G. doi:10.1126/science.1069424. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 12029063.

- ^ Altshuler, David; Donnelly, Peter; The International HapMap Consortium (October 2005). "A haplotype map of the human genome". Nature. 437 (7063): 1299–1320. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1299T. doi:10.1038/nature04226. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 1880871. PMID 16255080.

- ^ Slatkin, Montgomery (June 2008). "Linkage disequilibrium--understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 9 (6): 477–485. doi:10.1038/nrg2361. ISSN 1471-0064. PMC 5124487. PMID 18427557.

- ^ Wall, Jeffrey D.; Pritchard, Jonathan K. (September 2003). "Assessing the performance of the haplotype block model of linkage disequilibrium". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (3): 502–515. doi:10.1086/378099. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1180676. PMID 12916017.

- ^ Walker, Timothy M.; Ip, Camilla L. C.; Harrell, Ruth H.; Evans, Jason T.; Kapatai, Georgia; Dedicoat, Martin J.; Eyre, David W.; Wilson, Daniel J.; Hawkey, Peter M.; Crook, Derrick W.; Parkhill, Julian; Harris, David; Walker, A. Sarah; Bowden, Rory; Monk, Philip (February 2013). "Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 13 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70277-3. ISSN 1474-4457. PMC 3556524. PMID 23158499.

- ^ Price, Alkes L.; Patterson, Nick J.; Plenge, Robert M.; Weinblatt, Michael E.; Shadick, Nancy A.; Reich, David (August 2006). "Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies". Nature Genetics. 38 (8): 904–909. doi:10.1038/ng1847. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 16862161.

- ^ Carlson, Bruce (15 June 2008). "SNPs — A Shortcut to Personalized Medicine". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 28 (12). Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

(subtitle) Medical applications are where the market's growth is expected

- ^ a b Visscher, Peter M.; Wray, Naomi R.; Zhang, Qian; Sklar, Pamela; McCarthy, Mark I.; Brown, Matthew A.; Yang, Jian (July 2017). "10 Years of GWAS Discovery: Biology, Function, and Translation". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 101 (1): 5–22. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.005. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 5501872. PMID 28686856.

- ^ Dong, Linda M.; Potter, John D.; White, Emily; Ulrich, Cornelia M.; Cardon, Lon R.; Peters, Ulrike (2008-05-28). "Genetic Susceptibility to Cancer". JAMA. 299 (20): 2423–2436. doi:10.1001/jama.299.20.2423. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 2772197. PMID 18505952.

- ^ Alkuraya, Fowzan S. (April 2010). "Homozygosity mapping: One more tool in the clinical geneticist's toolbox". Genetics in Medicine. 12 (4): 236–239. doi:10.1097/gim.0b013e3181ceb95d. ISSN 1098-3600. PMID 20134328. S2CID 10789932.

- ^ Vohra, Manik; Sharma, Anu Radha; Prabhu B, Navya; Rai, Padmalatha S. (2020). "SNPs in Sites for DNA Methylation, Transcription Factor Binding, and miRNA Targets Leading to Allele-Specific Gene Expression and Contributing to Complex Disease Risk: A Systematic Review". Public Health Genomics. 23 (5–6): 155–170. doi:10.1159/000510253. ISSN 1662-4246. PMID 32966991. S2CID 221886624.

- ^ Wang, Jing; Ma, Xiaoqin; Zhang, Qi; Chen, Yinghui; Wu, Dan; Zhao, Pengjun; Yu, Yu (2021). "The Interaction Analysis of SNP Variants and DNA Methylation Identifies Novel Methylated Pathogenesis Genes in Congenital Heart Diseases". Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 9 665514. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.665514. ISSN 2296-634X. PMC 8143053. PMID 34041244.

- ^ a b Hawe, Johann S.; Wilson, Rory; Schmid, Katharina T.; Zhou, Li; Lakshmanan, Lakshmi Narayanan; Lehne, Benjamin C.; Kühnel, Brigitte; Scott, William R.; Wielscher, Matthias; Yew, Yik Weng; Baumbach, Clemens; Lee, Dominic P.; Marouli, Eirini; Bernard, Manon; Pfeiffer, Liliane (January 2022). "Genetic variation influencing DNA methylation provides insights into molecular mechanisms regulating genomic function". Nature Genetics. 54 (1): 18–29. doi:10.1038/s41588-021-00969-x. ISSN 1546-1718. PMC 7617265. PMID 34980917. S2CID 256821844.

- ^ Perzel Mandell, Kira A.; Eagles, Nicholas J.; Wilton, Richard; Price, Amanda J.; Semick, Stephen A.; Collado-Torres, Leonardo; Ulrich, William S.; Tao, Ran; Han, Shizhong; Szalay, Alexander S.; Hyde, Thomas M.; Kleinman, Joel E.; Weinberger, Daniel R.; Jaffe, Andrew E. (2021-09-02). "Genome-wide sequencing-based identification of methylation quantitative trait loci and their role in schizophrenia risk". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 5251. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.5251P. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25517-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8413445. PMID 34475392.

- ^ Hoffmann, Anke; Ziller, Michael; Spengler, Dietmar (December 2016). "The Future is The Past: Methylation QTLs in Schizophrenia". Genes. 7 (12): 104. doi:10.3390/genes7120104. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 5192480. PMID 27886132.

- ^ Daly, Ann K (2017-10-11). "Pharmacogenetics: a general review on progress to date". British Medical Bulletin. 124 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldx035. ISSN 0007-1420. PMID 29040422.

- ^ Musci, Rashelle J.; Augustinavicius, Jura L.; Volk, Heather (2019-08-13). "Gene-Environment Interactions in Psychiatry: Recent Evidence and Clinical Implications". Current Psychiatry Reports. 21 (9): 81. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1065-5. ISSN 1523-3812. PMC 7340157. PMID 31410638.

- ^ Giegling I, Hartmann AM, Möller HJ, Rujescu D (November 2006). "Anger- and aggression-related traits are associated with polymorphisms in the 5-HT-2A gene". Journal of Affective Disorders. 96 (1–2): 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.016. PMID 16814396.

- ^ Ezzeddini R, Somi MH, Taghikhani M, Moaddab SY, Masnadi Shirazi K, Shirmohammadi M, Eftekharsadat AT, Sadighi Moghaddam B, Salek Farrokhi A (February 2021). "Association of Foxp3 rs3761548 polymorphism with cytokines concentration in gastric adenocarcinoma patients". Cytokine. 138 155351. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155351. ISSN 1043-4666. PMID 33127257. S2CID 226218796.

- ^ Kujovich JL (January 2011). "Factor V Leiden thrombophilia". Genetics in Medicine. 13 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181faa0f2. PMID 21116184.

- ^ Morita A, Nakayama T, Doba N, Hinohara S, Mizutani T, Soma M (June 2007). "Genotyping of triallelic SNPs using TaqMan PCR". Molecular and Cellular Probes. 21 (3): 171–6. doi:10.1016/j.mcp.2006.10.005. PMID 17161935.

- ^ Prodi DA, Drayna D, Forabosco P, Palmas MA, Maestrale GB, Piras D, Pirastu M, Angius A (October 2004). "Bitter taste study in a sardinian genetic isolate supports the association of phenylthiocarbamide sensitivity to the TAS2R38 bitter receptor gene". Chemical Senses. 29 (8): 697–702. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjh074. PMID 15466815.

- ^ Ammitzbøll CG, Kjær TR, Steffensen R, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Nielsen HJ, Thiel S, Bøgsted M, Jensenius JC (28 November 2012). "Non-synonymous polymorphisms in the FCN1 gene determine ligand-binding ability and serum levels of M-ficolin". PLOS ONE. 7 (11) e50585. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750585A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050585. PMC 3509001. PMID 23209787.

- ^ Guenther, Catherine A.; Tasic, Bosiljka; Luo, Liqun; Bedell, Mary A.; Kingsley, David M. (July 2014). "A molecular basis for classic blond hair color in Europeans". Nature Genetics. 46 (7): 748–752. doi:10.1038/ng.2991. ISSN 1546-1718. PMC 4704868. PMID 24880339.

- ^ Ji G, Long Y, Zhou Y, Huang C, Gu A, Wang X (May 2012). "Common variants in mismatch repair genes associated with increased risk of sperm DNA damage and male infertility". BMC Medicine. 10 49. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-49. PMC 3378460. PMID 22594646.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information, United States National Library of Medicine. 2014. NCBI dbSNP build 142 for human. "[DBSNP-announce] DBSNP Human Build 142 (GRCh38 and GRCh37.p13)". Archived from the original on 2017-09-10. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information, United States National Library of Medicine. 2015. NCBI dbSNP build 144 for human. Summary Page. "DBSNP Summary". Archived from the original on 2017-09-10. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ Glusman G, Caballero J, Mauldin DE, Hood L, Roach JC (November 2011). "Kaviar: an accessible system for testing SNV novelty". Bioinformatics. 27 (22): 3216–7. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr540. PMC 3208392. PMID 21965822.

- ^ Cao R, Shi Y, Chen S, Ma Y, Chen J, Yang J, Chen G, Shi T (January 2017). "dbSAP: single amino-acid polymorphism database for protein variation detection". Nucleic Acids Research. 45 (D1): D827 – D832. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw1096. PMC 5210569. PMID 27903894.

- ^ Sachidanandam R, Weissman D, Schmidt SC, Kakol JM, Stein LD, Marth G, Sherry S, Mullikin JC, Mortimore BJ, Willey DL, Hunt SE, Cole CG, Coggill PC, Rice CM, Ning Z, Rogers J, Bentley DR, Kwok PY, Mardis ER, Yeh RT, Schultz B, Cook L, Davenport R, Dante M, Fulton L, Hillier L, Waterston RH, McPherson JD, Gilman B, Schaffner S, Van Etten WJ, Reich D, Higgins J, Daly MJ, Blumenstiel B, Baldwin J, Stange-Thomann N, Zody MC, Linton L, Lander ES, Altshuler D (February 2001). "A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms". Nature. 409 (6822): 928–33. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..928S. doi:10.1038/35057149. PMID 11237013.

- ^ "Clustered RefSNPs (rs) and Other Data Computed in House". SNP FAQ Archive. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2005.

- ^ J.T. Den Dunnen (2008-02-20). "Recommendations for the description of sequence variants". Human Genome Variation Society. Archived from the original on 2008-09-14. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE (2000). "Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion". Human Mutation. 15 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 10612815.

- ^ Ogino S, Gulley ML, den Dunnen JT, Wilson RB (February 2007). "Standard mutation nomenclature in molecular diagnostics: practical and educational challenges". The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 9 (1): 1–6. doi:10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060081. PMC 1867422. PMID 17251329.

- ^ "Sequence Variant Nomenclature". varnomen.hgvs.org. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ Johnson, Andrew D. (October 2009). "SNP bioinformatics: a comprehensive review of resources". Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2 (5): 530–536. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.872010. ISSN 1942-325X. PMC 2789466. PMID 20031630.

- ^ Malhis N, Jones SJ, Gsponer J (April 2019). "Improved measures for evolutionary conservation that exploit taxonomy distances". Nature Communications. 10 (1) 1556. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1556M. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09583-2. PMC 6450959. PMID 30952844.

- ^ Nawar Malhis; Matthew Jacobson; Steven J. M. Jones; Jörg Gsponer (2020). "LIST-S2: Taxonomy Based Sorting of Deleterious Missense Mutations Across Species". Nucleic Acids Research. 48 (W1): W154 – W161. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa288. PMC 7319545. PMID 32352516.

- ^ "View of SNPViz - Visualization of SNPs in proteins". genomicscomputbiol.org. doi:10.18547/gcb.2018.vol4.iss1.e100048. Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- ^ Ofoegbu TC, David A, Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Islam SA, Mersmann SF, et al. (June 2019). "PhyreRisk: A Dynamic Web Application to Bridge Genomics, Proteomics and 3D Structural Data to Guide Interpretation of Human Genetic Variants". Journal of Molecular Biology. 431 (13): 2460–2466. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.043. PMC 6597944. PMID 31075275.

- ^ Ittisoponpisan S, Islam SA, Khanna T, Alhuzimi E, David A, Sternberg MJ (May 2019). "Can Predicted Protein 3D Structures Provide Reliable Insights into whether Missense Variants Are Disease Associated?". Journal of Molecular Biology. 431 (11): 2197–2212. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.009. PMC 6544567. PMID 30995449.

Further reading

[edit]- "Glossary". Nature Reviews.

- Human Genome Project Information – SNP Fact Sheet

External links

[edit]- NCBI resources Archived 2013-09-02 at the Wayback Machine – Introduction to SNPs from NCBI

- The SNP Consortium LTD – SNP search

- NCBI dbSNP database – "a central repository for both single base nucleotide substitutions and short deletion and insertion polymorphisms"

- HGMD – the Human Gene Mutation Database, includes rare mutations and functional SNPs

- GWAS Central – a central database of summary-level genetic association findings

- 1000 Genomes Project – A Deep Catalog of Human Genetic Variation

- WatCut Archived 2007-06-18 at the Wayback Machine – an online tool for the design of SNP-RFLP assays

- SNPStats Archived 2008-10-13 at the Wayback Machine – SNPStats, a web tool for analysis of genetic association studies

- Restriction HomePage – a set of tools for DNA restriction and SNP detection, including design of mutagenic primers

- American Association for Cancer Research Cancer Concepts Factsheet on SNPs

- PharmGKB – The Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base, a resource for SNPs associated with drug response and disease outcomes.

- GEN-SNiP Archived 2010-01-19 at the Wayback Machine – Online tool that identifies polymorphisms in test DNA sequences.

- Rules for Nomenclature of Genes, Genetic Markers, Alleles, and Mutations in Mouse and Rat

- HGNC Guidelines for Human Gene Nomenclature

- SNP effect predictor with galaxy integration

- Open SNP – a portal for sharing own SNP test results

- dbSAP Archived 2016-12-20 at the Wayback Machine – SNP database for protein variation detection