Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Karyotype

View on WikipediaA karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes.[1][2] Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is discerned by determining the chromosome complement of an individual, including the number of chromosomes and any abnormalities.

A karyogram or idiogram is a graphical depiction of a karyotype, wherein chromosomes are generally organized in pairs, ordered by size and position of centromere for chromosomes of the same size. Karyotyping generally combines light microscopy and photography in the metaphase of the cell cycle, and results in a photomicrographic (or simply micrographic) karyogram. In contrast, a schematic karyogram is a designed graphic representation of a karyotype. In schematic karyograms, just one of the sister chromatids of each chromosome is generally shown for brevity, and in reality they are generally so close together that they look as one on photomicrographs as well unless the resolution is high enough to distinguish them. The study of whole sets of chromosomes is sometimes known as karyology.

Karyotypes describe the chromosome count of an organism and what these chromosomes look like under a light microscope. Attention is paid to their length, the position of the centromeres, banding pattern, any differences between the sex chromosomes, and any other physical characteristics.[3] The preparation and study of karyotypes is part of cytogenetics.

The basic number of chromosomes in the somatic cells of an individual or a species is called the somatic number and is designated 2n. In the germ-line (the sex cells) the chromosome number is n (humans: n = 23).[4][5]p28 Thus, in humans 2n = 46.

So, in normal diploid organisms, autosomal chromosomes are present in two copies. There may, or may not, be sex chromosomes. Polyploid cells have multiple copies of chromosomes and haploid cells have single copies.

Karyotypes can be used for many purposes; such as to study chromosomal aberrations, cellular function, taxonomic relationships, medicine and to gather information about past evolutionary events (karyosystematics).[6]

Observations on karyotypes

[edit]

Staining

[edit]The study of karyotypes is made possible by staining. Usually, a suitable dye, such as Giemsa,[8] is applied after cells have been arrested during cell division by a solution of colchicine usually in metaphase or prometaphase when most condensed. In order for the Giemsa stain to adhere correctly, all chromosomal proteins must be digested and removed. For humans, white blood cells are used most frequently because they are easily induced to divide and grow in tissue culture.[9] Sometimes observations may be made on non-dividing (interphase) cells. The sex of an unborn fetus can be predicted by observation of interphase cells (see amniotic centesis and Barr body).

Observations

[edit]Six different characteristics of karyotypes are usually observed and compared:[10]

- Differences in absolute sizes of chromosomes. Chromosomes can vary in absolute size by as much as twenty-fold between genera of the same family. For example, the legumes Lotus tenuis and Vicia faba each have six pairs of chromosomes, yet V. faba chromosomes are many times larger. These differences probably reflect different amounts of DNA duplication.

- Differences in the position of centromeres. These differences probably came about through translocations.

- Differences in relative size of chromosomes. These differences probably arose from segmental interchange of unequal lengths.

- Differences in basic number of chromosomes. These differences could have resulted from successive unequal translocations which removed all the essential genetic material from a chromosome, permitting its loss without penalty to the organism (the dislocation hypothesis) or through fusion. Humans have one pair fewer chromosomes than the great apes. Human chromosome 2 appears to have resulted from the fusion of two ancestral chromosomes, and many of the genes of those two original chromosomes have been translocated to other chromosomes.

- Differences in number and position of satellites. Satellites are small bodies attached to a chromosome by a thin thread.

- Differences in degree and distribution of GC content (Guanine-Cytosine pairs versus Adenine-Thymine). In metaphase where the karyotype is typically studied, all DNA is condensed, but most of the time, DNA with a high GC content is usually less condensed, that is, it tends to appear as euchromatin rather than heterochromatin. GC rich DNA tends to contain more coding DNA and be more transcriptionally active.[11] GC rich DNA is lighter on Giemsa staining.[12] Euchromatin regions contain larger amounts of Guanine-Cytosine pairs (that is, it has a higher GC content). The staining technique using Giemsa staining is called G banding and therefore produces the typical "G-Bands".[12]

A full account of a karyotype may therefore include the number, type, shape and banding of the chromosomes, as well as other cytogenetic information.

Variation is often found:

- between the sexes,

- between the germ-line and soma (between gametes and the rest of the body),

- between members of a population (chromosome polymorphism),

- in geographic specialization, and

- in mosaics or otherwise abnormal individuals.[13]

Human karyogram

[edit]

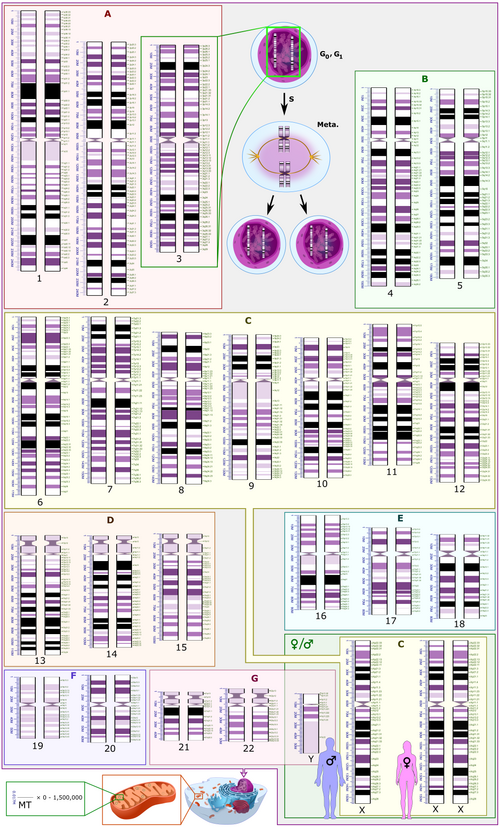

Both the micrographic and schematic karyograms shown in this section have a standard chromosome layout, and display darker and lighter regions as seen on G banding, which is the appearance of the chromosomes after treatment with trypsin (to partially digest the chromosomes) and staining with Giemsa stain. Compared to darker regions, the lighter regions are generally more transcriptionally active, with a greater ratio of coding DNA versus non-coding DNA, and a higher GC content.[11]

Both the micrographic and schematic karyograms show the normal human diploid karyotype, which is the typical composition of the genome within a normal cell of the human body, and which contains 22 pairs of autosomal chromosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes (allosomes). A major exception to diploidy in humans is gametes (sperm and egg cells) which are haploid with 23 unpaired chromosomes, and this ploidy is not shown in these karyograms. The micrographic karyogram is converted into grayscale, whereas the schematic karyogram shows the purple hue as typically seen on Giemsa stain (and is a result of its azure B component, which stains DNA purple).[14]

The schematic karyogram in this section is a graphical representation of the idealized karyotype. For each chromosome pair, the scale to the left shows the length in terms of million base pairs, and the scale to the right shows the designations of the bands and sub-bands. Such bands and sub-bands are used by the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature to describe locations of chromosome abnormalities. Each row of chromosomes is vertically aligned at centromere level.

Human chromosome groups

[edit]Based on the karyogram characteristics of size, position of the centromere and sometimes the presence of a chromosomal satellite (a segment distal to a secondary constriction), the human chromosomes are classified into the following groups:[15]

| Group | Chromosomes | Features |

|---|---|---|

| A | 1–3 | Large, metacentric or submetacentric |

| B | 4-5 | Large, submetacentric |

| C | 6–12, X | Medium-sized, submetacentric |

| D | 13–15 | Medium-sized, acrocentric, with satellite |

| E | 16–18 | Small, metacentric or submetacentric |

| F | 19–20 | Very small, metacentric |

| G | 21–22, Y | Very small, acrocentric (and 21, 22 with satellite) |

Alternatively, the human genome can be classified as follows, based on pairing, sex differences, as well as location within the cell nucleus versus inside mitochondria:

- 22 homologous autosomal chromosome pairs (chromosomes 1 to 22). Homologous means that they have the same genes in the same loci, and autosomal means that they are not sex chromomes.

- Two sex chromosome (in green rectangle at bottom right in the schematic karyogram, with adjacent silhouettes of typical representative phenotypes): The most common karyotypes for females contain two X chromosomes and are denoted 46,XX; males usually have both an X and a Y chromosome denoted 46,XY. However, approximately 0.018% percent of humans are intersex, sometimes due to variations in sex chromosomes.[16]

- The human mitochondrial genome (shown at bottom left in the schematic karyogram, to scale compared to the nuclear DNA in terms of base pairs), although this is not included in micrographic karyograms in clinical practice. Its genome is relatively tiny compared to the rest.

Copy number

[edit]

Schematic karyograms generally display a DNA copy number corresponding to the G0 phase of the cellular state (outside of the replicative cell cycle) which is the most common state of cells. The schematic karyogram in this section also shows this state. In this state (as well as during the G1 phase of the cell cycle), each cell has two autosomal chromosomes of each kind (designated 2n), where each chromosome has one copy of each locus, making a total copy number of two for each locus (2c). At top center in the schematic karyogram, it also shows the chromosome 3 pair after having undergone DNA synthesis, occurring in the S phase (annotated as S) of the cell cycle. This interval includes the G2 phase and metaphase (annotated as "Meta."). During this interval, there is still 2n, but each chromosome will have two copies of each locus, wherein each sister chromatid (chromosome arm) is connected at the centromere, for a total of 4c.[17] The chromosomes on micrographic karyograms are in this state as well, because they are generally micrographed in metaphase, but during this phase the two copies of each chromosome are so close to each other that they appear as one unless the image resolution is high enough to distinguish them. In reality, during the G0 and G1 phases, nuclear DNA is dispersed as chromatin and does not show visually distinguishable chromosomes even on micrography.

The copy number of the human mitochondrial genome per human cell varies from 0 (erythrocytes)[18] up to 1,500,000 (oocytes), mainly depending on the number of mitochondria per cell.[19]

Diversity and evolution of karyotypes

[edit]Although the replication and transcription of DNA is highly standardized in eukaryotes, the same cannot be said for their karyotypes, which are highly variable. There is variation between species in chromosome number, and in detailed organization, despite their construction from the same macromolecules. This variation provides the basis for a range of studies in evolutionary cytology.

In some cases there is even significant variation within species. In a review, Godfrey and Masters conclude:

In our view, it is unlikely that one process or the other can independently account for the wide range of karyotype structures that are observed ... But, used in conjunction with other phylogenetic data, karyotypic fissioning may help to explain dramatic differences in diploid numbers between closely related species, which were previously inexplicable.[20]

Although much is known about karyotypes at the descriptive level, and it is clear that changes in karyotype organization has had effects on the evolutionary course of many species, it is quite unclear what the general significance might be.

We have a very poor understanding of the causes of karyotype evolution, despite many careful investigations ... the general significance of karyotype evolution is obscure.

— Maynard Smith[21]

Changes during development

[edit]Instead of the usual gene repression, some organisms go in for large-scale elimination of heterochromatin, or other kinds of visible adjustment to the karyotype.

- Chromosome elimination. In some species, as in many sciarid flies, entire chromosomes are eliminated during development.[22]

- Chromatin diminution (founding father: Theodor Boveri). In this process, found in some copepods and roundworms such as Ascaris suum, portions of the chromosomes are cast away in particular cells. This process is a carefully organised genome rearrangement where new telomeres are constructed and certain heterochromatin regions are lost.[23][24] In A. suum, all the somatic cell precursors undergo chromatin diminution.[25]

- X-inactivation. The inactivation of one X chromosome takes place during the early development of mammals (see Barr body and dosage compensation). In placental mammals, the inactivation is random as between the two Xs; thus the mammalian female is a mosaic in respect of her X chromosomes. In marsupials it is always the paternal X which is inactivated. In human females some 15% of somatic cells escape inactivation,[26] and the number of genes affected on the inactivated X chromosome varies between cells: in fibroblast cells up about 25% of genes on the Barr body escape inactivation.[27]

Number of chromosomes in a set

[edit]A spectacular example of variability between closely related species is the muntjac, which was investigated by Kurt Benirschke and Doris Wurster. The diploid number of the Chinese muntjac, Muntiacus reevesi, was found to be 46, all telocentric. When they looked at the karyotype of the closely related Indian muntjac, Muntiacus muntjak, they were astonished to find it had female = 6, male = 7 chromosomes.[28]

They simply could not believe what they saw ... They kept quiet for two or three years because they thought something was wrong with their tissue culture ... But when they obtained a couple more specimens they confirmed [their findings].

— Hsu p. 73-4[29]

The number of chromosomes in the karyotype between (relatively) unrelated species is hugely variable. The low record is held by the nematode Parascaris univalens, where the haploid n = 1; and an ant: Myrmecia pilosula.[30] The high record would be somewhere amongst the ferns, with the adder's tongue fern Ophioglossum ahead with an average of 1262 chromosomes.[31] Top score for animals might be the shortnose sturgeon Acipenser brevirostrum at 372 chromosomes.[32] The existence of supernumerary or B chromosomes means that chromosome number can vary even within one interbreeding population; and aneuploids are another example, though in this case they would not be regarded as normal members of the population.

Fundamental number

[edit]The fundamental number, FN, of a karyotype is the number of visible major chromosomal arms per set of chromosomes.[33][34] Thus, FN ≤ 2 × 2n, the difference depending on the number of chromosomes considered single-armed (acrocentric or telocentric) present. Humans have FN = 82,[35] due to the presence of five acrocentric chromosome pairs: 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22 (the human Y chromosome is also acrocentric). The fundamental autosomal number or autosomal fundamental number, FNa[36] or AN,[37] of a karyotype is the number of visible major chromosomal arms per set of autosomes (non-sex-linked chromosomes).

Ploidy

[edit]Ploidy is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell.

- Polyploidy, where there are more than two sets of homologous chromosomes in the cells, occurs mainly in plants. It has been of major significance in plant evolution according to Stebbins.[38][39][40][41] The proportion of flowering plants which are polyploid was estimated by Stebbins to be 30–35%, but in grasses the average is much higher, about 70%.[42] Polyploidy in lower plants (ferns, horsetails and psilotales) is also common, and some species of ferns have reached levels of polyploidy far in excess of the highest levels known in flowering plants. Polyploidy in animals is much less common, but it has been significant in some groups.[43]

Polyploid series in related species which consist entirely of multiples of a single basic number are known as euploid.

- Haplo-diploidy, where one sex is diploid, and the other haploid. It is a common arrangement in the Hymenoptera, and in some other groups.

- Endopolyploidy occurs when in adult differentiated tissues the cells have ceased to divide by mitosis, but the nuclei contain more than the original somatic number of chromosomes.[44] In the endocycle (endomitosis or endoreduplication) chromosomes in a 'resting' nucleus undergo reduplication, the daughter chromosomes separating from each other inside an intact nuclear membrane.[45]

In many instances, endopolyploid nuclei contain tens of thousands of chromosomes (which cannot be exactly counted). The cells do not always contain exact multiples (powers of two), which is why the simple definition 'an increase in the number of chromosome sets caused by replication without cell division' is not quite accurate.

This process (especially studied in insects and some higher plants such as maize) may be a developmental strategy for increasing the productivity of tissues which are highly active in biosynthesis.[46]

The phenomenon occurs sporadically throughout the eukaryote kingdom from protozoa to humans; it is diverse and complex, and serves differentiation and morphogenesis in many ways.[47]

Aneuploidy

[edit]Aneuploidy is the condition in which the chromosome number in the cells is not the typical number for the species. This would give rise to a chromosome abnormality such as an extra chromosome or one or more chromosomes lost. Abnormalities in chromosome number usually cause a defect in development. Down syndrome and Turner syndrome are examples of this.

Aneuploidy may also occur within a group of closely related species. Classic examples in plants are the genus Crepis, where the gametic (= haploid) numbers form the series x = 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7; and Crocus, where every number from x = 3 to x = 15 is represented by at least one species. Evidence of various kinds shows that trends of evolution have gone in different directions in different groups.[48] In primates, the great apes have 24x2 chromosomes whereas humans have 23x2. Human chromosome 2 was formed by a merger of ancestral chromosomes, reducing the number.[49]

Chromosomal polymorphism

[edit]Some species are polymorphic for different chromosome structural forms.[50] The structural variation may be associated with different numbers of chromosomes in different individuals, which occurs in the ladybird beetle Chilocorus stigma, some mantids of the genus Ameles,[51] the European shrew Sorex araneus.[52] There is some evidence from the case of the mollusc Thais lapillus (the dog whelk) on the Brittany coast, that the two chromosome morphs are adapted to different habitats.[53]

Species trees

[edit]The detailed study of chromosome banding in insects with polytene chromosomes can reveal relationships between closely related species: the classic example is the study of chromosome banding in Hawaiian drosophilids by Hampton L. Carson.

In about 6,500 sq mi (17,000 km2), the Hawaiian Islands have the most diverse collection of drosophilid flies in the world, living from rainforests to subalpine meadows. These roughly 800 Hawaiian drosophilid species are usually assigned to two genera, Drosophila and Scaptomyza, in the family Drosophilidae.

The polytene banding of the 'picture wing' group, the best-studied group of Hawaiian drosophilids, enabled Carson to work out the evolutionary tree long before genome analysis was practicable. In a sense, gene arrangements are visible in the banding patterns of each chromosome. Chromosome rearrangements, especially inversions, make it possible to see which species are closely related.

The results are clear. The inversions, when plotted in tree form (and independent of all other information), show a clear "flow" of species from older to newer islands. There are also cases of colonization back to older islands, and skipping of islands, but these are much less frequent. Using K-Ar dating, the present islands date from 0.4 million years ago (mya) (Mauna Kea) to 10mya (Necker). The oldest member of the Hawaiian archipelago still above the sea is Kure Atoll, which can be dated to 30 mya. The archipelago itself (produced by the Pacific Plate moving over a hot spot) has existed for far longer, at least into the Cretaceous. Previous islands now beneath the sea (guyots) form the Emperor Seamount Chain.[54]

All of the native Drosophila and Scaptomyza species in Hawaiʻi have apparently descended from a single ancestral species that colonized the islands, probably 20 million years ago. The subsequent adaptive radiation was spurred by a lack of competition and a wide variety of niches. Although it would be possible for a single gravid female to colonise an island, it is more likely to have been a group from the same species.[55][56][57][58]

There are other animals and plants on the Hawaiian archipelago which have undergone similar, if less spectacular, adaptive radiations.[59][60]

Chromosome banding

[edit]Chromosomes display a banded pattern when treated with some stains. Bands are alternating light and dark stripes that appear along the lengths of chromosomes. Unique banding patterns are used to identify chromosomes and to diagnose chromosomal aberrations, including chromosome breakage, loss, duplication, translocation or inverted segments. A range of different chromosome treatments produce a range of banding patterns: G-bands, R-bands, C-bands, Q-bands, T-bands and NOR-bands.

Depiction of karyotypes

[edit]Types of banding

[edit]Cytogenetics employs several techniques to visualize different aspects of chromosomes:[9]

- G-banding is obtained with Giemsa stain following digestion of chromosomes with trypsin. It yields a series of lightly and darkly stained bands — the dark regions tend to be heterochromatic, late-replicating and AT rich. The light regions tend to be euchromatic, early-replicating and GC rich. This method will normally produce 300–400 bands in a normal, human genome. It is the most common chromosome banding method.[61]

- R-banding is the reverse of G-banding (the R stands for "reverse"). The dark regions are euchromatic (guanine-cytosine rich regions) and the bright regions are heterochromatic (thymine-adenine rich regions).

- C-banding: Giemsa binds to constitutive heterochromatin, so it stains centromeres. The name is derived from centromeric or constitutive heterochromatin. The preparations undergo alkaline denaturation prior to staining leading to an almost complete depurination of the DNA. After washing the probe the remaining DNA is renatured again and stained with Giemsa solution consisting of methylene azure, methylene violet, methylene blue, and eosin. Heterochromatin binds a lot of the dye, while the rest of the chromosomes absorb only little of it. The C-bonding proved to be especially well-suited for the characterization of plant chromosomes.

- Q-banding is a fluorescent pattern obtained using quinacrine for staining. The pattern of bands is very similar to that seen in G-banding. They can be recognized by a yellow fluorescence of differing intensity. Most part of the stained DNA is heterochromatin. Quinacrin (atebrin) binds both regions rich in AT and in GC, but only the AT-quinacrin-complex fluoresces. Since regions rich in AT are more common in heterochromatin than in euchromatin, these regions are labelled preferentially. The different intensities of the single bands mirror the different contents of AT. Other fluorochromes like DAPI or Hoechst 33258 lead also to characteristic, reproducible patterns. Each of them produces its specific pattern. In other words: the properties of the bonds and the specificity of the fluorochromes are not exclusively based on their affinity to regions rich in AT. Rather, the distribution of AT and the association of AT with other molecules like histones, for example, influences the binding properties of the fluorochromes.

- T-banding: visualize telomeres.

- Silver staining: Silver nitrate stains the nucleolar organization region-associated protein. This yields a dark region where the silver is deposited, denoting the activity of rRNA genes within the NOR.

Classic karyotype cytogenetics

[edit]

In the "classic" (depicted) karyotype, a dye, often Giemsa (G-banding), less frequently mepacrine (quinacrine), is used to stain bands on the chromosomes. Giemsa is specific for the phosphate groups of DNA. Quinacrine binds to the adenine-thymine-rich regions. Each chromosome has a characteristic banding pattern that helps to identify them; both chromosomes in a pair will have the same banding pattern.

Karyotypes are arranged with the short arm of the chromosome on top, and the long arm on the bottom. Some karyotypes call the short and long arms p and q, respectively. In addition, the differently stained regions and sub-regions are given numerical designations from proximal to distal on the chromosome arms. For example, Cri du chat syndrome involves a deletion on the short arm of chromosome 5. It is written as 46,XX,5p-. The critical region for this syndrome is deletion of p15.2 (the locus on the chromosome), which is written as 46,XX,del(5)(p15.2).[62]

Multicolor FISH (mFISH) and spectral karyotype (SKY technique)

[edit]

Multicolor FISH and the older spectral karyotyping are molecular cytogenetic techniques used to simultaneously visualize all the pairs of chromosomes in an organism in different colors. Fluorescently labeled probes for each chromosome are made by labeling chromosome-specific DNA with different fluorophores. Because there are a limited number of spectrally distinct fluorophores, a combinatorial labeling method is used to generate many different colors. Fluorophore combinations are captured and analyzed by a fluorescence microscope using up to 7 narrow-banded fluorescence filters or, in the case of spectral karyotyping, by using an interferometer attached to a fluorescence microscope. In the case of an mFISH image, every combination of fluorochromes from the resulting original images is replaced by a pseudo color in a dedicated image analysis software. Thus, chromosomes or chromosome sections can be visualized and identified, allowing for the analysis of chromosomal rearrangements.[63] In the case of spectral karyotyping, image processing software assigns a pseudo color to each spectrally different combination, allowing the visualization of the individually colored chromosomes.[64]

Multicolor FISH is used to identify structural chromosome aberrations in cancer cells and other disease conditions when Giemsa banding or other techniques are not accurate enough.

Digital karyotyping

[edit]Digital karyotyping is a technique used to quantify the DNA copy number on a genomic scale. Short sequences of DNA from specific loci all over the genome are isolated and enumerated.[65] This method is also known as virtual karyotyping. Using this technique, it is possible to detect small alterations in the human genome, that cannot be detected through methods employing metaphase chromosomes. Some loci deletions are known to be related to the development of cancer. Such deletions are found through digital karyotyping using the loci associated with cancer development.[66]

Chromosome abnormalities

[edit]Chromosome abnormalities can be numerical, as in the presence of extra or missing chromosomes, or structural, as in derivative chromosome, translocations, inversions, large-scale deletions or duplications. Numerical abnormalities, also known as aneuploidy, often occur as a result of nondisjunction during meiosis in the formation of a gamete; trisomies, in which three copies of a chromosome are present instead of the usual two, are common numerical abnormalities. Structural abnormalities often arise from errors in homologous recombination. Both types of abnormalities can occur in gametes and therefore will be present in all cells of an affected person's body, or they can occur during mitosis and give rise to a genetic mosaic individual who has some normal and some abnormal cells.

In humans

[edit]Chromosomal abnormalities that lead to disease in humans include

- Turner syndrome results from a single X chromosome (45,X or 45,X0).

- Klinefelter syndrome, the most common male chromosomal disease, otherwise known as 47,XXY, is caused by an extra X chromosome.

- Edwards syndrome is caused by trisomy (three copies) of chromosome 18.

- Down syndrome, a common chromosomal disease, is caused by trisomy of chromosome 21.

- Patau syndrome is caused by trisomy of chromosome 13.

- Trisomy 9, believed to be the 4th most common trisomy, has many long lived affected individuals but only in a form other than a full trisomy, such as trisomy 9p syndrome or mosaic trisomy 9. They often function quite well, but tend to have trouble with speech.

- Also documented are trisomy 8 and trisomy 16, although they generally do not survive to birth.

Some disorders arise from loss of just a piece of one chromosome, including

- Cri du chat (cry of the cat), from a truncated short arm on chromosome 5. The name comes from the babies' distinctive cry, caused by abnormal formation of the larynx.

- 1p36 Deletion syndrome, from the loss of part of the short arm of chromosome 1.

- Angelman syndrome – 50% of cases have a segment of the long arm of chromosome 15 missing; a deletion of the maternal genes, example of imprinting disorder.

- Prader-Willi syndrome – 50% of cases have a segment of the long arm of chromosome 15 missing; a deletion of the paternal genes, example of imprinting disorder.

- Chromosomal abnormalities can also occur in cancerous cells of an otherwise genetically normal individual; one well-documented example is the Philadelphia chromosome, a translocation mutation commonly associated with chronic myelogenous leukemia and less often with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

History of karyotype studies

[edit]Chromosomes were first observed in plant cells by Carl Wilhelm von Nägeli in 1842. Their behavior in animal (salamander) cells was described by Walther Flemming, the discoverer of mitosis, in 1882. The name was coined by another German anatomist, Heinrich von Waldeyer in 1888. It is Neo-Latin from Ancient Greek κάρυον karyon, "kernel", "seed", or "nucleus", and τύπος typos, "general form")

The next stage took place after the development of genetics in the early 20th century, when it was appreciated that chromosomes (that can be observed by karyotype) were the carrier of genes. The term karyotype as defined by the phenotypic appearance of the somatic chromosomes, in contrast to their genic contents was introduced by Grigory Levitsky who worked with Lev Delaunay, Sergei Navashin, and Nikolai Vavilov.[67][68][69][70] The subsequent history of the concept can be followed in the works of C. D. Darlington[71] and Michael JD White.[4][13]

Investigation into the human karyotype took many years to settle the most basic question: how many chromosomes does a normal diploid human cell contain?[72] In 1912, Hans von Winiwarter reported 47 chromosomes in spermatogonia and 48 in oogonia, concluding an XX/XO sex determination mechanism.[73] Painter in 1922 was not certain whether the diploid of humans was 46 or 48, at first favoring 46,[74] but revised his opinion from 46 to 48, and he correctly insisted on humans having an XX/XY system.[75] Considering the techniques of the time, these results were remarkable.

Joe Hin Tjio working in Albert Levan's lab[76] found the chromosome count to be 46 using new techniques available at the time:

- Using cells in tissue culture

- Pretreating cells in a hypotonic solution, which swells them and spreads the chromosomes

- Arresting mitosis in metaphase by a solution of colchicine

- Squashing the preparation on the slide forcing the chromosomes into a single plane

- Cutting up a photomicrograph and arranging the result into an indisputable karyogram.

The work took place in 1955, and was published in 1956. The karyotype of humans includes only 46 chromosomes.[77][29] The other great apes have 48 chromosomes. Human chromosome 2 is now known to be a result of an end-to-end fusion of two ancestral ape chromosomes.[78][79]

See also

[edit]- Cytogenetic notation – Symbols and abbreviations used in cytogenetics

- Genome screen – Laboratory process

References

[edit]- ^ "Karyotype, definition". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Judd, Walter S.; Campbell, Christopher S.; Kellogg, Elizabeth A.; Stevens, Peter F.; Donoghue, Michael J. (2002). Plant systematics, a phylogenetic approach (2 ed.). Sunderland MA, US: Sinauer Associates Inc. p. 544. ISBN 0-87893-403-0.

- ^ King, R.C.; Stansfield, W.D.; Mulligan, P.K. (2006). A dictionary of genetics (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 242.

- ^ a b White 1973, p. 35

- ^ Stebbins, G.L. (1950). "Chapter XII: The Karyotype". Variation and evolution in plants. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-01733-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Karyosystematics".

- ^ Lee M. Silver (1995). Mouse Genetics, Concepts and Applications. Chapter 5.2: KARYOTYPES, CHROMOSOMES, AND TRANSLOCATIONS. Oxford University Press. Revised August 2004, January 2008

- ^ A preparation which includes the dyes Methylene Blue, Eosin Y and Azure-A,B,C

- ^ a b Gustashaw K.M. 1991. Chromosome stains. In The ACT Cytogenetics Laboratory Manual 2nd ed, ed. M.J. Barch. The Association of Cytogenetic Technologists, Raven Press, New York.

- ^ Stebbins, G.L. (1971). Chromosomal evolution in higher plants. London: Arnold. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-7131-2287-9.

- ^ a b Romiguier J, Roux C (2017). "Analytical Biases Associated with GC-Content in Molecular Evolution". Front Genet. 8: 16. doi:10.3389/fgene.2017.00016. PMC 5309256. PMID 28261263.

- ^ a b Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine 7th Ed

- ^ a b White M.J.D. 1973. Animal cytology and evolution. 3rd ed, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ K. Lew (2012). Comprehensive Sampling and Sample Preparation. Chapter: 3.05 - Blood Sample Collection and Handling. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-381374-9.

- ^ Erwinsyah, R.; Riandi & Nurjhani, M. (2017). "Relevance of human chromosome analysis activities against mutation concept in genetics course". IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 180 012285. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/180/1/012285. S2CID 90739754.

- ^ Sax, L. (2002). "How Common is Intersex?". Journal of Sex Research. 39 (3): 174–178. doi:10.1080/00224490209552139. PMID 12476264. S2CID 33795209.

- ^ Gomes CJ, Harman MW, Centuori SM, Wolgemuth CW, Martinez JD (2018). "Measuring DNA content in live cells by fluorescence microscopy". Cell Div. 13 6. doi:10.1186/s13008-018-0039-z. PMC 6123973. PMID 30202427.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shuster RC, Rubenstein AJ, Wallace DC (1988). "Mitochondrial DNA in anucleate human blood cells". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 155 (3): 1360–5. doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81291-9. PMID 3178814.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhang D, Keilty D, Zhang ZF, Chian RC (2017). "Mitochondria in oocyte aging: current understanding". Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 9 (1): 29–38. PMC 5506767. PMID 28721182.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Godfrey LR, Masters JC (August 2000). "Kinetochore reproduction theory may explain rapid chromosome evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (18): 9821–3. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.9821G. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.18.9821. PMC 34032. PMID 10963652.

- ^ Maynard Smith J. 1998. Evolutionary genetics. 2nd ed, Oxford. p218-9

- ^ Goday C, Esteban MR (March 2001). "Chromosome elimination in sciarid flies". BioEssays. 23 (3): 242–50. doi:10.1002/1521-1878(200103)23:3<242::AID-BIES1034>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 11223881. S2CID 43718856.

- ^ Müller F, Bernard V, Tobler H (February 1996). "Chromatin diminution in nematodes". BioEssays. 18 (2): 133–8. doi:10.1002/bies.950180209. PMID 8851046. S2CID 24583845.

- ^ Wyngaard GA, Gregory TR (December 2001). "Temporal control of DNA replication and the adaptive value of chromatin diminution in copepods". J. Exp. Zool. 291 (4): 310–6. Bibcode:2001JEZ...291..310W. doi:10.1002/jez.1131. PMID 11754011.

- ^ Gilbert S.F. 2006. Developmental biology. Sinauer Associates, Stamford CT. 8th ed, Chapter 9

- ^ King, Stansfield & Mulligan 2006

- ^ Carrel L, Willard H (2005). "X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females". Nature. 434 (7031): 400–404. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..400C. doi:10.1038/nature03479. PMID 15772666. S2CID 4358447.

- ^ Wurster DH, Benirschke K (June 1970). "Indian muntjac, Muntiacus muntjak: a deer with a low diploid chromosome number". Science. 168 (3937): 1364–6. Bibcode:1970Sci...168.1364W. doi:10.1126/science.168.3937.1364. PMID 5444269. S2CID 45371297.

- ^ a b Hsu T.C. 1979. Human and mammalian cytogenetics: a historical perspective. Springer-Verlag, NY.

- ^ Crosland M.W.J.; Crozier, R.H. (1986). "Myrmecia pilosula, an ant with only one pair of chromosomes". Science. 231 (4743): 1278. Bibcode:1986Sci...231.1278C. doi:10.1126/science.231.4743.1278. PMID 17839565. S2CID 25465053.

- ^ Khandelwal S. (1990). "Chromosome evolution in the genus Ophioglossum L". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 102 (3): 205–217. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1990.tb01876.x.

- ^ Kim, D.S.; Nam, Y.K.; Noh, J.K.; Park, C.H.; Chapman, F.A. (2005). "Karyotype of North American shortnose sturgeon Acipenser brevirostrum with the highest chromosome number in the Acipenseriformes". Ichthyological Research. 52 (1): 94–97. Bibcode:2005IchtR..52...94K. doi:10.1007/s10228-004-0257-z. S2CID 20126376.

- ^ Matthey, R. (15 May 1945). "L'evolution de la formule chromosomiale chez les vertébrés". Experientia (Basel). 1 (2): 50–56. doi:10.1007/BF02153623. S2CID 38524594.

- ^ de Oliveira, R.R.; Feldberg, E.; dos Anjos, M. B.; Zuanon, J. (July–September 2007). "Karyotype characterization and ZZ/ZW sex chromosome heteromorphism in two species of the catfish genus Ancistrus Kner, 1854 (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the Amazon basin". Neotropical Ichthyology. 5 (3): 301–6. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252007000300010.

- ^ Pellicciari, C.; Formenti, D.; Redi, C. A.; Manfredi, M. G.; Romanini (February 1982). "DNA content variability in primates". Journal of Human Evolution. 11 (2): 131–141. Bibcode:1982JHumE..11..131P. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(82)80045-6.

- ^ Souza, A. L. G.; de O. Corrêa, M. M.; de Aguilar, C. T.; Pessôa, L. M. (February 2011). "A new karyotype of Wiedomys pyrrhorhinus (Rodentia: Sigmodontinae) from Chapada Diamantina, northeastern Brazil" (PDF). Zoologia. 28 (1): 92–96. doi:10.1590/S1984-46702011000100013.

- ^ Weksler, M.; Bonvicino, C. R. (3 January 2005). "Taxonomy of pygmy rice rats genus Oligoryzomys Bangs, 1900 (Rodentia, Sigmodontinae) of the Brazilian Cerrado, with the description of two new species" (PDF). Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 63 (1): 113–130. ISSN 0365-4508. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ Stebbins, G. L. (1940). "The significance of polyploidy in plant evolution". The American Naturalist. 74 (750): 54–66. Bibcode:1940ANat...74...54S. doi:10.1086/280872. S2CID 86709379.

- ^ Stebbins 1950

- ^ Comai, L. (November 2005). "The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid". Nature Reviews Genetics. 6 (11): 836–46. doi:10.1038/nrg1711. PMID 16304599. S2CID 3329282.

- ^ Adams KL, Wendel JF (April 2005). "Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 8 (2): 135–141. Bibcode:2005COPB....8..135A. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.001. PMID 15752992.

- ^ Stebbins 1971

- ^ Gregory, T. R.; Mable, B. K. (2011). "Ch. 8: Polyploidy in animals". In Gregory, T. Ryan (ed.). The Evolution of the Genome. Academic Press. pp. 427–517. ISBN 978-0-08-047052-8.

- ^ White, M. J. D. (1973). The chromosomes (6th ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. p. 45.

- ^ Lilly, M. A.; Duronio, R. J. (2005). "New insights into cell cycle control from the Drosophila endocycle". Oncogene. 24 (17): 2765–75. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1208610. PMID 15838513.

- ^ Edgar BA, Orr-Weaver TL (May 2001). "Endoreplication cell cycles: more for less". Cell. 105 (3): 297–306. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00334-8. PMID 11348589. S2CID 14368177.

- ^ Nagl, W. (1978). Endopolyploidy and polyteny in differentiation and evolution: towards an understanding of quantitative and qualitative variation of nuclear DNA in ontogeny and phylogeny. New York: Elsevier.

- ^ Stebbins, G. Ledley, Jr. 1972. Chromosomal evolution in higher plants. Nelson, London. p18

- ^ IJdo JW, Baldini A, Ward DC, Reeders ST, Wells RA (October 1991). "Origin of human chromosome 2: an ancestral telomere-telomere fusion". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (20): 9051–5. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.9051I. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.20.9051. PMC 52649. PMID 1924367.

- ^ Rieger, R.; Michaelis, A.; Green, M.M. (1968). A glossary of genetics and cytogenetics: Classical and molecular. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-07668-3.

- ^ Gustavsson, Ingemar (3 March 1969). "Cytogenetics, distribution and phenotypic effects of a translocation in Swedish cattle". Hereditas. 63 (1–2): 68–169. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5223.1969.tb02259.x. PMID 5399228.

- ^ Searle, J. B. (1 June 1984). "Three New Karyotypic Races of the Common Shrew Sorex Araneus (Mammalia: Insectivora) and a Phylogeny". Systematic Biology. 33 (2): 184–194. doi:10.1093/sysbio/33.2.184. ISSN 1063-5157.

- ^ White 1973, p. 169

- ^ Clague, D.A.; Dalrymple, G.B. (1987). "The Hawaiian-Emperor volcanic chain, Part I. Geologic evolution" (PDF). In Decker, R.W.; Wright, T.L.; Stauffer, P.H. (eds.). Volcanism in Hawaii. Vol. 1. pp. 5–54. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1350. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Carson HL (June 1970). "Chromosome tracers of the origin of species". Science. 168 (3938): 1414–8. Bibcode:1970Sci...168.1414C. doi:10.1126/science.168.3938.1414. PMID 5445927.

- ^ Carson HL (March 1983). "Chromosomal sequences and interisland colonizations in Hawaiian Drosophila". Genetics. 103 (3): 465–82. doi:10.1093/genetics/103.3.465. PMC 1202034. PMID 17246115.

- ^ Carson H.L. (1992). "Inversions in Hawaiian Drosophila". In Krimbas, C.B.; Powell, J.R. (eds.). Drosophila inversion polymorphism. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press. pp. 407–439. ISBN 978-0-8493-6547-8.

- ^ Kaneshiro, K.Y.; Gillespie, R.G.; Carson, H.L. (1995). "Chromosomes and male genitalia of Hawaiian Drosophila: tools for interpreting phylogeny and geography". In Wagner, W.L.; Funk, E. (eds.). Hawaiian biogeography: evolution on a hot spot archipelago. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 57–71.

- ^ Craddock E.M. (2000). "Speciation Processes in the Adaptive Radiation of Hawaiian Plants and Animals". In Hecht, Max K.; MacIntyre, Ross J.; Clegg, Michael T. (eds.). Evolutionary Biology. Vol. 31. pp. 1–43. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4185-1_1. ISBN 978-1-4613-6877-9.

- ^ Ziegler, Alan C. (2002). Hawaiian natural history, ecology, and evolution. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2190-6.

- ^ Maloy, Stanley R.; Hughes, Kelly (2013). Brenner's Encyclopedia of Genetics. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-096156-9. OCLC 836404630.

- ^ Lisa G. Shaffer; Niels Tommerup, eds. (2005). ISCN 2005: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Switzerland: S. Karger AG. ISBN 978-3-8055-8019-9.

- ^ Liehr T, Starke H, Weise A, Lehrer H, Claussen U (January 2004). "Multicolour FISH probe sets and their applications". Histol. Histopathol. 19 (1): 229–237. PMID 14702191.

- ^ Schröck E, du Manoir S, Veldman T, et al. (July 1996). "Multicolor spectral karyotyping of human chromosomes". Science. 273 (5274): 494–7. Bibcode:1996Sci...273..494S. doi:10.1126/science.273.5274.494. PMID 8662537. S2CID 22654725.

- ^ Wang TL, Maierhofer C, Speicher MR, et al. (December 2002). "Digital karyotyping". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (25): 16156–61. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916156W. doi:10.1073/pnas.202610899. PMC 138581. PMID 12461184.

- ^ Leary, Rebecca J; Cummins, Jordan; Wang, Tian-Li; Velculescu, Victor E (August 2007). "Digital karyotyping". Nature Protocols. 2 (8): 1973–1986. doi:10.1038/nprot.2007.276. ISSN 1754-2189. PMID 17703209. S2CID 33337972.

- ^ Zelenin, A. V.; Rodionov, A. V.; Bolsheva, N. L.; Badaeva, E. D.; Muravenko, O. V. (2016). "Genome: Origins and evolution of the term". Molecular Biology. 50 (4): 542–550. doi:10.1134/S0026893316040178. ISSN 0026-8933. PMID 27668601. S2CID 9373640.

- ^ Vermeesch, Joris Robert; Rauch, Anita (2006). "Reply to Hochstenbach et al". European Journal of Human Genetics. 14 (10): 1063–1064. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201663. ISSN 1018-4813. PMID 16736034. S2CID 46363277.

- ^ Delaunay L. N. Comparative karyological study of species Muscari Mill. and Bellevalia Lapeyr. Bulletin of the Tiflis Botanical Garden. 1922, v. 2, n. 1, p. 1-32[in Russian]

- ^ Battaglia, Emilio (1994). "Nucleosome and nucleotype: a terminological criticism". Caryologia. 47 (3–4): 193–197. doi:10.1080/00087114.1994.10797297.

- ^ Darlington C.D. 1939. Evolution of genetic systems. Cambridge University Press. 2nd ed, revised and enlarged, 1958. Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh.

- ^ MJ, Kottler (1974). "From 48 to 46: cytological technique, preconception, and the counting of human chromosomes". Bull Hist Med. 48 (4): 465–502. PMID 4618149.

- ^ von Winiwarter H. (1912). "Études sur la spermatogenèse humaine". Archives de Biologie. 27 (93): 147–9.

- ^ Painter T.S. (1922). "The spermatogenesis of man". Anat. Res. 23: 129.

- ^ Painter T.S. (1923). "Studies in mammalian spermatogenesis II". J. Exp. Zoology. 37 (3): 291–336. doi:10.1002/jez.1400370303.

- ^ Wright, Pearce (11 December 2001). "Joe Hin Tjio The man who cracked the chromosome count". The Guardian.

- ^ Tjio J.H.; Levan A. (1956). "The chromosome number of man". Hereditas. 42 (1–2): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5223.1956.tb03010.x. PMID 345813.

- ^ Human chromosome 2 is a fusion of two ancestral. chromosomes Alec MacAndrew; accessed 18 May 2006.

- ^ Evidence of common ancestry: human chromosome 2 (video) 2007

External links

[edit] Media related to Karyotypes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Karyotypes at Wikimedia Commons- Making a karyotype, an online activity from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center.

- Karyotyping activity with case histories from the University of Arizona's Biology Project.

- Printable karyotype project from Biology Corner, a resource site for biology and science teachers.

- Chromosome Staining and Banding Techniques

- Bjorn Biosystems for Karyotyping and FISH Archived 12 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine

Karyotype

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Key Characteristics

A karyotype is the complete set of chromosomes of an organism, characterized by their number, size, shape, and banding patterns within the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell.[1][4] This chromosomal complement provides a snapshot of the organism's genetic material at the structural level, distinct from the genome, which encompasses the full sequence of DNA across all chromosomes.[1] Key characteristics of a karyotype include the diploid chromosome number, denoted as 2n, representing the paired set of chromosomes in somatic cells of diploid organisms.[5] The shape of individual chromosomes is primarily determined by the position of the centromere, which can be classified as metacentric (centrally located, producing arms of equal length), submetacentric (slightly off-center), acrocentric (near one end, with a very short arm), or telocentric (at the terminal end).[6][7] The centromere divides each chromosome into a shorter p (petite) arm and a longer q (queue) arm.[8] Additionally, certain chromosomes feature secondary constrictions, such as nucleolar organizer regions (NORs), which are sites of ribosomal RNA gene clusters involved in nucleolus formation.[9] Karyotypes are typically examined during the metaphase stage of mitosis, when chromosomes are fully condensed and aligned, making their number, size, and morphology clearly visible under a microscope.[5] This analysis applies exclusively to eukaryotic cells, as prokaryotes lack true chromosomes and instead possess a single circular DNA molecule in a nucleoid region without a membrane-bound nucleus.[10] A karyotype is often represented visually as a karyogram, an organized photographic display of the chromosomes arranged by size and type.[1]Karyogram as a Visual Representation

A karyogram is a visual representation of the complete set of chromosomes derived from a single cell, systematically arranged to facilitate analysis of their number, size, and morphology. This organized image, often produced from cells arrested in metaphase, allows researchers to identify chromosomal features and detect potential abnormalities. Unlike the abstract concept of a karyotype, which refers to the inherent characteristics of an organism's chromosome complement, the karyogram provides a concrete, pictorial depiction for study and comparison.[11] The preparation of a karyogram begins with culturing cells, such as those from blood, bone marrow, or amniotic fluid, to ensure active division. Mitotic arrest is induced using agents like colchicine or colcemid, which disrupt spindle formation and halt cells at metaphase when chromosomes are maximally condensed and visible. Cells are then subjected to hypotonic treatment to swell and separate chromosomes, followed by fixation with a methanol-acetic acid solution to preserve structure. The fixed cells are dropped onto a slide to spread the chromosomes, stained for visibility, and photographed under a microscope. Individual chromosomes are then cut out from the image and manually or digitally arranged into the final karyogram.[12] In the karyogram, homologous chromosome pairs are positioned side by side and ordered from largest to smallest, with the sex chromosomes (X and Y) placed last. This arrangement follows established conventions, initially outlined by the Denver classification in 1960, which grouped human chromosomes into seven categories (A through G) based on decreasing size and centromere position. Subsequent standardization came from the Paris Conference in 1971, which refined nomenclature to include banding patterns while maintaining the core ordering principles for clarity and consistency in cytogenetic reporting. The landmark publication of the first detailed human karyograms occurred in 1956 by Joe Hin Tjio and Albert Levan, who used improved culturing and photographic techniques to accurately count 46 chromosomes, correcting prior estimates of 48.[13]Visualization Techniques

Staining and Banding Methods

Staining and banding methods are essential techniques in cytogenetics for visualizing chromosomes and revealing their structural details during karyotype preparation. Basic staining provides overall contrast to chromosomes, with Giemsa stain commonly used to highlight chromatin density and produce a general outline of metaphase chromosomes under light microscopy.[14] Quinacrine staining, on the other hand, induces fluorescence in chromosomes, particularly useful for early identification of specific regions like the long arm of the Y chromosome due to its affinity for AT-rich DNA sequences.[15] Banding techniques build on these stains by creating distinct patterns of light and dark bands along chromosomes, enabling precise identification and detection of abnormalities. G-banding, the most widely adopted method, involves treating chromosomes with trypsin to partially digest proteins, followed by Giemsa staining, which results in dark G-bands corresponding to AT-rich, gene-poor regions and light bands in GC-rich areas; it was introduced and standardized at the Paris Conference in 1971, becoming the gold standard for clinical cytogenetics.[16] R-banding, or reverse banding, achieves the opposite pattern by heating chromosomes in a saline buffer (typically at 85°C) before Giemsa staining, preferentially staining GC-rich telomeric regions dark while leaving centromeric areas light.[17] C-banding specifically targets constitutive heterochromatin, primarily in centromeric and pericentromeric regions, through treatment with alkali (such as 0.07 M NaOH) to denature DNA, followed by saline incubation and Giemsa staining, which highlights repetitive, AT-rich sequences.[18] T-banding, a variant of R-banding, further emphasizes telomeres by using higher heat denaturation (around 87°C) or additional steps to strongly stain the terminal GC-rich regions while faintly staining the rest of the chromosome arms.[19] The resolution of these banding methods varies by technique and preparation quality, typically resolving 400 to 850 bands per haploid set (bphs), where 400 bphs offers basic identification, 550 bphs provides intermediate detail, and 850 bphs enables detection of microdeletions or duplications as small as 5-10 megabases.[20] These patterns are crucial in classical karyotyping for identifying structural variants like deletions, duplications, and translocations by comparing band positions against standardized ideograms.[21]Classical and Spectral Karyotyping

Classical karyotyping begins with the harvesting of metaphase chromosomes from cultured cells, typically derived from blood, bone marrow, or tissue samples. Cells are stimulated to divide using mitogens like phytohemagglutinin for lymphocytes, followed by arrest in metaphase with colchicine or Colcemid to depolymerize microtubules and accumulate condensed chromosomes.[22] A hypotonic solution, such as 0.075 M potassium chloride, is then applied to swell the cells, facilitating chromosome spreading, after which cells are fixed in a methanol-acetic acid mixture (typically 3:1 ratio) to preserve structure.[12] Slide preparation involves dropping the fixed cell suspension from a height of 30-50 cm onto clean, chilled glass slides to rupture cells and disperse chromosomes evenly, followed by air-drying at controlled humidity (around 50%) and temperature (20-25°C) to prevent aggregation.[23] Slides are briefly treated with staining and banding methods, such as Giemsa for G-banding, to reveal characteristic patterns for chromosome identification. Under a light microscope, analysts select well-spread metaphase spreads, capture images, and manually pair homologous chromosomes based on size, centromere position, and banding patterns before arranging them into a karyogram, a standardized idiogram for analysis.[24] Spectral karyotyping (SKY), developed in 1996, extends classical methods by integrating fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with spectral imaging for whole-genome visualization. It employs a set of 24 chromosome-specific painting probes, each labeled with a unique combination of five fluorochromes, to hybridize to metaphase chromosomes, "painting" each of the 22 autosomes and sex chromosomes in a distinct pseudo-color. The emitted fluorescence spectra are captured using an interferometer and separated via Fourier spectroscopy, allowing software to assign unique spectral signatures to each chromosome pair, even in complex rearrangements.[25] Multicolor FISH (mFISH), introduced concurrently in 1996, operates similarly to SKY for whole-chromosome painting but relies on combinatorial labeling with 5-7 fluorochromes and multiple bandpass filters rather than spectral separation, enabling software-based color assignment for all 24 human chromosomes.[26] While SKY excels in spectral resolution for distinguishing overlapping signals, mFISH offers flexibility for locus-specific probes targeting centromeres or gene regions, providing higher resolution for detecting subtle translocations and insertions not visible in classical karyotypes.[27] SKY has proven particularly valuable in tumor cytogenetics, where it facilitates the identification of marker chromosomes and complex structural abnormalities in cancer cells, such as those in hematological malignancies, by revealing hidden translocations and derivatives that banding alone cannot resolve.[28]Molecular and Emerging Techniques

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) represents a pivotal molecular technique in karyotyping, employing fluorescently labeled DNA probes that hybridize to specific chromosomal loci, enabling the visualization of targeted genetic sequences under fluorescence microscopy. This method surpasses classical banding by allowing precise localization of genes or chromosomal regions, facilitating the detection of microdeletions, amplifications, and translocations not resolvable by standard cytogenetics.[29] Variants such as multicolor FISH (M-FISH) extend this capability by using multiple fluorophores to simultaneously label and distinguish all chromosomes in a karyotype, proving essential for unraveling complex rearrangements in clinical samples.[30] Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) further advances molecular karyotyping by comparing test DNA from a sample to reference DNA, both hybridized to normal metaphase spreads or microarray platforms, to identify copy number imbalances across the genome. Introduced in 1992, CGH detects gains and losses of chromosomal material without prior knowledge of specific loci, offering a genome-wide profile of aneuploidy and segmental alterations at resolutions down to 5-10 Mb in its classical form.[31] Array-based CGH (aCGH) refines this approach with oligonucleotide or BAC arrays, achieving sub-megabase resolution and enabling high-throughput screening for structural variants in uncultured cells.[32] Digital karyotyping provides a sequencing-based alternative, utilizing a SAGE-like protocol to generate millions of short genomic tags from restriction enzyme-digested DNA, which are sequenced and mapped to quantify copy number at loci spaced approximately 1 kb apart. Developed in 2002, this method delivers quantitative, high-resolution DNA content analysis without reliance on metaphase preparations, identifying amplifications and deletions in complex genomes like human cancer cells.[33] Emerging techniques in the 2020s, such as optical genome mapping (OGM), leverage nanotechnology to image ultra-long DNA molecules labeled at specific motifs, producing contig maps that reveal structural variants including large insertions, inversions, and balanced translocations with resolutions exceeding 500 bp. OGM excels in detecting complex rearrangements overlooked by traditional karyotyping, for example, a 2023 multicenter study on acute myeloid leukemia identified clinically relevant structural variants and copy number variations in 13% of cases missed by routine cytogenetic methods, with findings altering clinical management in 4% and affecting trial eligibility in 8%.[34] Complementing this, artificial intelligence (AI)-guided karyotyping employs deep neural networks to automate metaphase image analysis, chromosome segmentation, and abnormality classification, achieving accuracies of 97% in diverse specimen types and reducing manual processing time by over 50% in clinical laboratories.[35] These AI models, advanced between 2023 and 2025, integrate convolutional layers for feature extraction, enhancing throughput while maintaining diagnostic precision for routine cytogenetic workflows.[36]Analysis and Observations

Chromosome Number and Fundamental Features

The chromosome number in a karyotype refers to the total count of chromosomes in a cell, with most eukaryotic organisms exhibiting a diploid (2n) configuration in somatic cells, consisting of two sets of chromosomes—one inherited from each parent—while gametes are haploid (n), containing a single set.[1] For instance, humans have a haploid number of n=23, resulting in a diploid number of 2n=46 in somatic cells. In contrast, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster has a haploid number of n=4, yielding a diploid number of 2n=8.[37] The fundamental number (FN), also known as the number of chromosome arms (NF), quantifies the total major arms across the diploid set, serving as a key metric in cytotaxonomy to compare karyotypic evolution and relatedness among species.[38] Biarmed chromosomes, such as metacentric or submetacentric types with distinct p (short) and q (long) arms, contribute two arms each to the FN, whereas uniarmed acrocentric or telocentric chromosomes, featuring a single prominent arm, contribute one.[39] In humans, with predominantly biarmed chromosomes including short arms on acrocentrics, the FN equals 92.[40] For the house mouse (Mus musculus), despite a diploid number of 2n=40 composed entirely of acrocentric autosomes, the FN is 40, reflecting the uniarmed nature of these chromosomes.[41] Fundamental structural elements of chromosomes visible in karyotypes include telomeres, centromeres, and kinetochores, which ensure stability, segregation, and attachment during cell division. Telomeres cap the ends of linear chromosomes, comprising repetitive DNA sequences and associated proteins that prevent end-to-end fusions and degradation. Centromeres are specialized pericentromeric regions rich in repetitive DNA, serving as sites for kinetochore assembly to facilitate microtubule attachment and proper chromosome alignment on the mitotic spindle.[42] Kinetochores are multilayered protein complexes assembled on centromeric DNA, acting as the interface for spindle fibers to pull sister chromatids apart.[42]Copy Number, Ploidy, and Polymorphisms

Copy number variation (CNV) refers to structural alterations in the genome involving gains or losses of DNA segments ranging from 1 kilobase to several megabases, which can affect gene dosage and contribute to phenotypic diversity within populations. These variations are typically submicroscopic and not visible in standard karyograms but can be detected using high-resolution techniques such as array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH), which compares the hybridization intensity of test and reference DNA to genomic arrays to identify copy number imbalances.[43] Array CGH, first demonstrated in 1998, enables precise mapping of CNVs across the genome with resolutions down to 50-100 kilobases, surpassing traditional karyotyping.[43] Ploidy describes the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, with haploidy (n) featuring one set, as seen in gametes of many organisms, diploidy (2n) being the standard in most somatic cells of animals and many plants, and polyploidy (3n or more) occurring naturally in various species, such as triploidy (3n) in certain plants like seedless watermelons that enhances fruit size and vigor.[44] Polyploidy arises through mechanisms like whole-genome duplication and is particularly prevalent in plants, where it drives speciation and adaptation, with over 15% of angiosperm speciation events linked to polyploid origins.[45] In development, endoreduplication—a form of polyploidy—involves repeated DNA replication without cell division, leading to highly polyploid cells that support rapid growth, as observed in Drosophila larval tissues or plant endosperm.[46] Chromosomal polymorphisms encompass heritable variations in chromosome structure or morphology that occur at frequencies greater than 1% in populations, including pericentric inversions and heterochromatin size variants, which do not typically alter gene content but may influence recombination rates.[47] Pericentric inversions, which reverse segments around the centromere, are found in approximately 1-2% of individuals and are often balanced, with higher frequencies in certain ethnic groups due to founder effects.[48] Heterochromatin variants, such as enlarged pericentric regions denoted as qh+, commonly affect chromosomes 1, 9, and 16; for instance, the 1qh+ variant, involving expanded heterochromatin on the long arm of chromosome 1, occurs in about 1-2% of human populations based on cytogenetic surveys, though reported frequencies vary by study and ethnicity up to 20-30% in some cohorts when including subtle enlargements.[49][50] Aneuploidy represents a specific deviation from balanced ploidy, characterized by the gain or loss of individual chromosomes, such as monosomy (2n-1), which disrupts gene balance and is detectable in karyotypes as an abnormal chromosome count.[51]Human Karyotype

Normal Human Configuration

The normal human karyotype is diploid, comprising 46 chromosomes arranged in 23 pairs, including 22 pairs of autosomes numbered 1 through 22 and one pair of sex chromosomes.[52] Females typically have two X chromosomes (46,XX), while males have one X and one Y chromosome (46,XY).[53] This configuration was established in 1956 through cytogenetic analysis of human cells, confirming 46 as the modal chromosome number across multiple tissue samples.[54] In metaphase, the autosomes form 5 metacentric pairs (chromosomes 1, 3, 16, 19, 20), 12 submetacentric pairs (chromosomes 2, 4–12, 17, 18), and 5 acrocentric pairs (chromosomes 13–15, 21, 22), with the total length of the condensed chromosome set measuring approximately 200 μm.[55] Metacentric chromosomes have the centromere positioned centrally, resulting in two arms of nearly equal length; submetacentric chromosomes feature an off-center centromere, producing one longer arm; and acrocentric chromosomes have the centromere near one end, often with short stalks and satellites on the shorter arm.[56] The X chromosome is submetacentric and larger, with distinct short (p) and long (q) arms containing essential genes for various functions.[56] In contrast, the Y chromosome is small and acrocentric, primarily determining male sex through genes like SRY on its long arm.[57] Both sex chromosomes include pseudoautosomal regions—short homologous segments at the tips of their p and q arms—that facilitate pairing and recombination during male meiosis, ensuring proper segregation.[58] These regions, PAR1 on the short arms and PAR2 on the long arms, span about 2.6 Mb and 0.33 Mb, respectively, and contain genes expressed in both sexes.[59]Chromosome Groups and Nomenclature

Human chromosomes are organized into seven morphological groups, labeled A through G, based on their relative size, the position of the centromere, and other structural features. This classification system originated from the Denver Conference in 1960, which established a standard for identifying chromosomes without banding techniques, and was refined at the Paris Conference in 1971 to incorporate banding patterns for greater precision in clinical cytogenetics.[60][61] The groups are as follows:| Group | Chromosomes | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| A | 1–3 | Large, metacentric or submetacentric |

| B | 4–5 | Large, submetacentric |

| C | 6–12, X | Medium-sized, submetacentric |

| D | 13–15 | Medium-sized, acrocentric with satellites |

| E | 16–18 | Small, metacentric/submetacentric |

| F | 19–20 | Very small, metacentric |

| G | 21–22, Y | Very small, acrocentric |