Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Syllable

View on WikipediaA syllable is a basic unit of organization within a sequence of speech sounds, such as within a word, typically defined by linguists as a nucleus (most often a vowel) with optional sounds before or after that nucleus (margins, which are most often consonants). In phonology and studies of languages, syllables are often considered the "building blocks" of words.[1] They can influence the rhythm of a language: its prosody or poetic metre. Properties such as stress, tone and reduplication operate on syllables and their parts.[2] Speech can usually be divided up into a whole number of syllables: for example, the word ignite is made of two syllables: ig and nite. Most languages of the world use relatively simple syllable structures that often alternate between vowels and consonants.[3]

Despite being present in virtually all human languages, syllables still have no precise definition that is valid for all known languages.[2] A common criterion for finding syllable boundaries is native-speaker intuition, but individuals sometimes disagree on them.[4]

Syllabic writing began several hundred years before the first instances of alphabetic writing. The earliest recorded syllables are on tablets written around 2800 BC in the Sumerian city of Ur. This shift from pictograms to syllables has been called "the most important advance in the history of writing".[5]

A word that consists of a single syllable (like English dog) is called a monosyllable (and is said to be monosyllabic). Similar terms include disyllable (and disyllabic; also bisyllable and bisyllabic) for a word of two syllables; trisyllable (and trisyllabic) for a word of three syllables; and polysyllable (and polysyllabic), which may refer either to a word of more than three syllables or to any word of more than one syllable.

Etymology

[edit]Syllable is an Anglo-Norman variation of Old French sillabe, from Latin syllaba, from Koine Greek συλλαβή syllabḗ (Ancient Greek pronunciation: [sylːabɛ̌ː]). συλλαβή means "the taken together", referring to letters that are taken together to make a single sound.[6]

συλλαβή is a verbal noun from the verb συλλαμβάνω syllambánō, a compound of the preposition σύν sýn "with" and the verb λαμβάνω lambánō "take".[7] The noun uses the root λαβ-, which appears in the aorist tense; the present tense stem λαμβάν- is formed by adding a nasal infix ⟨μ⟩ ⟨m⟩ before the β b and a suffix -αν -an at the end.[8]

Transcription

[edit]In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), the fullstop ⟨.⟩ marks syllable breaks, as in the word "astronomical" ⟨/ˌæs.trə.ˈnɒm.ɪk.əl/⟩.

In practice, however, IPA transcription is typically divided into words by spaces, and often these spaces are also understood to be syllable breaks. In addition, the stress mark ⟨ˈ⟩ is placed immediately before a stressed syllable, and when the stressed syllable is in the middle of a word, in practice, the stress mark also marks a syllable break, for example in the word "understood" ⟨/ʌndərˈstʊd/⟩ (though the syllable boundary may still be explicitly marked with a full stop,[9] e.g. ⟨/ʌn.dər.ˈstʊd/⟩).

When a word space comes in the middle of a syllable (that is, when a syllable spans words), a tie bar ⟨‿⟩ can be used for liaison, as in the French combination les amis ⟨/lɛ.z‿a.mi/⟩. The liaison tie is also used to join lexical words into phonological words, for example hot dog ⟨/ˈhɒt‿dɒɡ/⟩.

A Greek sigma, ⟨σ⟩, is used as a wild card for 'syllable', and a dollar/peso sign, ⟨$⟩, marks a syllable boundary where the usual fullstop might be misunderstood. For example, ⟨σσ⟩ is a pair of syllables, and ⟨V$⟩ is a syllable-final vowel.

Components

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2025) |

Onset–nucleus–rime segmentation

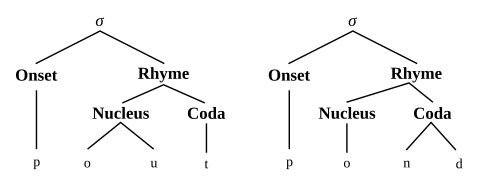

[edit]In this framework, the general structure of a syllable (σ) consists of three segments grouped into two components:

- Onset (ω): A consonant or consonant cluster, obligatory in some languages, optional or even restricted in others

- Rime (ρ): Right branch, contrasts with onset, splits into nucleus and coda

- Nucleus (ν): A vowel or syllabic consonant, obligatory in most languages

- Coda (κ): A consonant or consonant cluster, optional in some languages, highly restricted or prohibited in others

The syllable is usually considered right-branching, i.e. nucleus and coda are grouped together as a "rime" and are only distinguished at the second level.

The sounds occupying these positions may also be denoted with the following notation:

- Consonant (C, or, for a consonant from a idiosyncratic set of possibilities, X)

- Obstruent (T)

- Nasal consonant (N)

- Liquid consonant (L)

- Glide (G, or, less often, H)

- Vowel (V)

- Tone (T, or, if there is a risk of confusion with an obstruent, T)

- an exact phoneme or even phone (any specific IPA symbol)

possibly with the following notation to indicate occurrence count:

- "Exactly one" (no exponent)

- "Zero or one" (surrounding parentheses or, more rarely, ? after the letter)

- "Zero or more" (* after the letter)

- "One or more" (+ after the letter)

The nucleus is usually the vowel in the middle of a syllable.[10] The onset is the sound or sounds occurring before the nucleus, and the coda (literally 'tail') is the sound or sounds that follow the nucleus. They are sometimes collectively known as the shell. The term rime covers the nucleus plus coda. In the one-syllable English word cat, the nucleus is a (the sound that can be shouted or sung on its own), the onset c, the coda t, and the rime at. This syllable can be abstracted as a consonant-vowel-consonant syllable, abbreviated CVC. Languages vary greatly in the restrictions on the sounds making up the onset, nucleus and coda of a syllable, according to what is termed a language's phonotactics.

Although every syllable has supra-segmental features, these are usually ignored if not semantically relevant, e.g. in tonal languages.

Chinese segmentation

[edit]

In the syllable structure of Sinitic languages, the onset is replaced with an initial, and a semivowel or liquid forms another segment, called the medial. These four segments are grouped into two slightly different components:[example needed]

- Initial ⟨ι⟩: Optional onset, excluding semivowels

- Final ⟨φ⟩: Medial, nucleus, and final consonant[11]

- Tone ⟨τ⟩: May be carried by the syllable as a whole or by the rime

In many languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, such as Chinese, the syllable structure is expanded to include an additional, optional medial segment located between the onset (often termed the initial in this context) and the rime. The medial is normally a semivowel, but reconstructions of Old Chinese generally include liquid medials (/r/ in modern reconstructions, /l/ in older versions), and many reconstructions of Middle Chinese include a medial contrast between /i/ and /j/, where the /i/ functions phonologically as a glide rather than as part of the nucleus. In addition, many reconstructions of both Old and Middle Chinese include complex medials such as /rj/, /ji/, /jw/ and /jwi/. The medial groups phonologically with the rime rather than the onset, and the combination of medial and rime is collectively known as the final.

Some linguists, especially when discussing the modern Chinese varieties, use the terms "final" and "rime" interchangeably. In historical Chinese phonology, however, the distinction between "final" (including the medial) and "rime" (not including the medial) is important in understanding the rime dictionaries and rime tables that form the primary sources for Middle Chinese, and as a result most authors distinguish the two according to the above definition.

Grouping of components

[edit]

In some theories of phonology, syllable structures are displayed as tree diagrams (similar to the trees found in some types of syntax). Not all phonologists agree that syllables have internal structure; in fact, some phonologists doubt the existence of the syllable as a theoretical entity.[13]

There are many arguments for a hierarchical relationship, rather than a linear one, between the syllable constituents. One hierarchical model groups the syllable nucleus and coda into an intermediate level, the rime. The hierarchical model accounts for the role that the nucleus+coda constituent plays in verse (i.e., rhyming words such as cat and bat are formed by matching both the nucleus and coda, or the entire rime), and for the distinction between heavy and light syllables, which plays a role in phonological processes such as, for example, sound change in Old English scipu and wordu, where in a process called high vowel deletion (HVD), the nominative/accusative plural of single light-syllable roots (like "*scip-") got a "u" ending in OE, whereas heavy syllable roots (like "*word-") would not, giving "scip-u" but "word-∅".[14][15][16]

Body

[edit]

In some traditional descriptions of certain languages such as Cree and Ojibwe, the syllable is considered left-branching, i.e. onset and nucleus group below a higher-level unit, called a "body" or "core". This contrasts with the coda.

Rime

[edit]The rime or rhyme of a syllable consists of a nucleus and an optional coda. It is the part of the syllable used in most poetic rhymes, and the part that is lengthened or stressed when a person elongates or stresses a word in speech.

The rime is usually the portion of a syllable from the first vowel to the end. For example, /æt/ is the rime of all of the words at, sat, and flat. However, the nucleus does not necessarily need to be a vowel in some languages, such as English. For instance, the rime of the second syllables of the words bottle and fiddle is just /l/, a liquid consonant.

Just as the rime branches into the nucleus and coda, the nucleus and coda may each branch into multiple phonemes. The limit for the number of phonemes which may be contained in each varies by language. For example, Japanese and most Sino-Tibetan languages do not have consonant clusters at the beginning or end of syllables, whereas many Eastern European languages can have more than two consonants at the beginning or end of the syllable. In English, the onset may have up to three consonants, and the coda four.[17]

Rime and rhyme are variants of the same word, but the rarer form rime is sometimes used to mean specifically syllable rime to differentiate it from the concept of poetic rhyme. This distinction is not made by some linguists and does not appear in most dictionaries.

| structure: | syllable = | onset | + rhyme |

|---|---|---|---|

| C+V+C*: | C1(C2)V1(V2)(C3)(C4) = | C1(C2) | + V1(V2)(C3)(C4) |

| V+C*: | V1(V2)(C3)(C4) = | ∅ | + V1(V2)(C3)(C4) |

Weight

[edit]

A heavy syllable is generally one with a branching rime, i.e. it is either a closed syllable that ends in a consonant, or a syllable with a branching nucleus, i.e. a long vowel or diphthong. The name is a metaphor, based on the nucleus or coda having lines that branch in a tree diagram.

In some languages, heavy syllables include both VV (branching nucleus) and VC (branching rime) syllables, contrasted with V, which is a light syllable. In other languages, only VV syllables are considered heavy, while both VC and V syllables are light. Some languages distinguish a third type of superheavy syllable, which consists of VVC syllables (with both a branching nucleus and rime) or VCC syllables (with a coda consisting of two or more consonants) or both.

In moraic theory, heavy syllables are said to have two moras, while light syllables are said to have one and superheavy syllables are said to have three. Japanese phonology is generally described this way.

Many languages forbid superheavy syllables, while a significant number forbid any heavy syllable. Some languages strive for constant syllable weight; for example, in stressed, non-final syllables in Italian, short vowels co-occur with closed syllables while long vowels co-occur with open syllables, so that all such syllables are heavy (not light or superheavy).

The difference between heavy and light frequently determines which syllables receive stress – this is the case in Latin and Arabic, for example. The system of poetic meter in many classical languages, such as Classical Greek, Classical Latin, Old Tamil and Sanskrit, is based on syllable weight rather than stress (so-called quantitative rhythm or quantitative meter).

Syllabification

[edit]Syllabification is the separation of a word into syllables, whether spoken or written. In most languages, the actually spoken syllables are the basis of syllabification in writing too. Due to the very weak correspondence between sounds and letters in the spelling of modern English, for example, written syllabification in English has to be based mostly on etymological i.e. morphological instead of phonetic principles. English written syllables therefore do not correspond to the actually spoken syllables of the living language.

Phonotactic rules determine which sounds are allowed or disallowed in each part of the syllable. English allows very complicated syllables; syllables may begin with up to three consonants (as in strength), and occasionally end with as many as four[17] (as in angsts, pronounced [æŋsts]). Many other languages are much more restricted; Japanese, for example, only allows /ɴ/ and a chroneme in a coda, and theoretically has no consonant clusters at all, as the onset is composed of at most one consonant.[18]

The linking of a word-final consonant to a vowel beginning the word immediately following it forms a regular part of the phonetics of some languages, including Spanish, Hungarian, and Turkish. Thus, in Spanish, the phrase los hombres ('the men') is pronounced [loˈsom.bɾes], Hungarian az ember ('the human') as [ɒˈzɛm.bɛr], and Turkish nefret ettim ('I hated it') as [nefˈɾe.tet.tim]. In Italian, a final [j] sound can be moved to the next syllable in enchainement, sometimes with a gemination: e.g., non ne ho mai avuti ('I've never had any of them') is broken into syllables as [non.neˈɔ.ma.jaˈvuːti] and io ci vado e lei anche ('I go there and she does as well') is realized as [jo.tʃiˈvaːdo.e.lɛjˈjaŋ.ke]. A related phenomenon, called consonant mutation, is found in the Celtic languages like Irish and Welsh, whereby unwritten (but historical) final consonants affect the initial consonant of the following word.

Ambisyllabicity

[edit]There can be disagreement about the location of some divisions between syllables in spoken language. The problems of dealing with such cases have been most commonly discussed with relation to English. In the case of a word such as hurry, the division may be /hʌr.i/ or /hʌ.ri/, neither of which seems a satisfactory analysis for a non-rhotic accent such as RP (British English): /hʌr.i/ results in a syllable-final /r/, which is not normally found, while /hʌ.ri/ gives a syllable-final short stressed vowel, which is also non-occurring. Arguments can be made in favour of one solution or the other: A general rule has been proposed that states that "Subject to certain conditions ..., consonants are syllabified with the more strongly stressed of two flanking syllables",[19] while many other phonologists prefer to divide syllables with the consonant or consonants attached to the following syllable wherever possible. However, an alternative that has received some support is to treat an intervocalic consonant as ambisyllabic, i.e. belonging both to the preceding and to the following syllable: /hʌṛi/. This is discussed in more detail in English phonology § Phonotactics.

Onset

[edit]The onset (also known as anlaut) is the consonant sound or sounds at the beginning of a syllable, occurring before the nucleus. Most syllables have an onset. Syllables without an onset may be said to have an empty, zero or null onset – that is, nothing where the onset would be.

Onset cluster

[edit]Some languages restrict onsets to be only a single consonant, while others allow multiconsonant onsets according to various rules. For example, in English, onsets such as pr-, pl- and tr- are possible but tl- is not, and sk- is possible but ks- is not. In Greek, however, both ks- and tl- are possible onsets, while contrarily in Classical Arabic no multiconsonant onsets are allowed at all.

Onset clusters often follow the sonority principle, that is, onsets with increasing sonority (/kl/) are usually preferred to ones with a plateau (/ll/) and even stronger preferred to decreasing sonority (/lk/); however, many languages have counterexamples to this tendency.[20]

Null onset

[edit]Some languages forbid null onsets. In these languages, words beginning in a vowel, like the English word at, are impossible.

This is less strange than it may appear at first, as most such languages allow syllables to begin with a phonemic glottal stop (the sound in the middle of English uh-oh or, in some dialects, the double T in button, represented in the IPA as /ʔ/). In English, a word that begins with a vowel may be pronounced with an epenthetic glottal stop when following a pause, though the glottal stop may not be a phoneme in the language.

Few languages make a phonemic distinction between a word beginning with a vowel and a word beginning with a glottal stop followed by a vowel, since the distinction will generally only be audible following another word. However, Maltese and some Polynesian languages do make such a distinction, as in Hawaiian /ahi/ ('fire') and /ʔahi/ ← /kahi/ ('tuna') and Maltese /∅/ ← Arabic /h/ and Maltese /k~ʔ/ ← Arabic /q/.

Ashkenazi and Sephardi Hebrew may commonly ignore א, ה and ע, and Arabic forbids empty onsets. The names Israel, Abel, Abraham, Omar, Abdullah, and Iraq appear not to have onsets in the first syllable, but in the original Hebrew and Arabic forms they actually begin with various consonants: the semivowel /j/ in יִשְׂרָאֵל yisra'él, the glottal fricative in /h/ הֶבֶל heḇel, the glottal stop /ʔ/ in אַבְרָהָם 'aḇrāhām, or the pharyngeal fricative /ʕ/ in عُمَر ʿumar, عَبْدُ ٱللّٰ ʿabdu llāh, and عِرَاق ʿirāq. Conversely, the Arrernte language of central Australia may prohibit onsets altogether; if so, all syllables have the underlying shape VC(C).[21]

The difference between a syllable with a null onset and one beginning with a glottal stop is often purely a difference of phonological analysis, rather than the actual pronunciation of the syllable. In some cases, the pronunciation of a (putatively) vowel-initial word when following another word – particularly, whether or not a glottal stop is inserted – indicates whether the word should be considered to have a null onset. For example, many Romance languages such as Spanish never insert such a glottal stop, while English does so only some of the times, depending on factors such as conversation speed; in both cases, this suggests that the words in question are truly vowel-initial.

But there are exceptions here, too. For example, standard German (excluding many southern accents) and Arabic both require that a glottal stop be inserted between a word and a following, putatively vowel-initial word. Yet such words are perceived to begin with a vowel in German but a glottal stop in Arabic. The reason for this has to do with other properties of the two languages. For example, a glottal stop does not occur in other situations in German, e.g. before a consonant or at the end of word. On the other hand, in Arabic, not only does a glottal stop occur in such situations (e.g. Classical /saʔala/ "he asked", /raʔj/ "opinion", /dˤawʔ/ "light"), but it occurs in alternations that are clearly indicative of its phonemic status (cf. Classical /kaːtib/ "writer" vs. /maktuːb/ "written", /ʔaːkil/ "eater" vs. /maʔkuːl/ "eaten"). In other words, while the glottal stop is predictable in German (inserted only if a stressed syllable would otherwise begin with a vowel),[22] the same sound is a regular consonantal phoneme in Arabic. The status of this consonant in the respective writing systems corresponds to this difference: there is no reflex of the glottal stop in German orthography, but there is a letter for it in the Arabic alphabet (Hamza (ء)).

The writing system of a language may not correspond with the phonological analysis of the language in terms of its handling of (potentially) null onsets. For example, in some languages written in the Latin alphabet, an initial glottal stop is left unwritten (see the German example); on the other hand, some languages written using non-Latin alphabets such as abjads and abugidas have a special zero consonant to represent a null onset. As an example, in Hangul, the alphabet of the Korean language, a null onset is represented with ㅇ at the left or top section of a grapheme, as in 역 "station", pronounced yeok, where the diphthong yeo is the nucleus and k is the coda.

Nucleus

[edit]| Word | Nucleus |

|---|---|

| cat [kæt] | [æ] |

| bed [bɛd] | [ɛ] |

| ode [oʊd] | [oʊ] |

| beet [bit] | [i] |

| bite [baɪt] | [aɪ] |

| rain [ɻeɪn] | [eɪ] |

| bitten [ˈbɪt.ən] or [ˈbɪt.n̩] |

[ɪ] [ə] or [n̩] |

The nucleus is usually the vowel in the middle of a syllable. Generally, every syllable requires a nucleus (sometimes called the peak), and the minimal syllable consists only of a nucleus, as in the English words "eye" or "owe". The syllable nucleus is usually a vowel, in the form of a monophthong, diphthong, or triphthong, but sometimes is a syllabic consonant.

It has been suggested that if a language allows a type of consonants to occur in syllable nucleus, it will also allow all the consonant types that are higher in sonority, that is, a language with syllabic fricatives would necessarily also have syllabic nasals, and that syllabic obstruents will be much more rare than liquids; both statements have been shown to be false.[23]

In most Germanic languages, lax vowels can occur only in closed syllables. Therefore, these vowels are also called checked vowels, as opposed to the tense vowels that are called free vowels because they can occur even in open syllables.

Consonant nucleus

[edit]Some languages allow obstruents to occur in the syllable nucleus without any intervening vowel or sonorant.[10] The most common syllabic consonants are sonorants like [l], [r], [m], [n] or [ŋ], as in English bottle or in Slovak krv [krv].[10] However, English allows syllabic obstruents in a few para-verbal onomatopoeic utterances such as shh (used to command silence) and psst (used to attract attention). All of these have been analyzed as phonemically syllabic. Obstruent-only syllables also occur phonetically in some prosodic situations when unstressed vowels elide between obstruents, as in potato [pʰˈteɪɾəʊ] and today [tʰˈdeɪ], which do not change in their number of syllables despite losing a syllabic nucleus.

A few languages have so-called syllabic fricatives, also known as fricative vowels, at the phonemic level. (In the context of Chinese phonology, the related but non-synonymous term apical vowel is commonly used.) Mandarin Chinese allows such sounds in at least some of its dialects, for example the pinyin syllables sī shī rī, usually pronounced [sź̩ ʂʐ̩́ ʐʐ̩́], respectively. Though, like the nucleus of rhotic English church, there is debate over whether these nuclei are consonants or vowels.

Languages of the northwest coast of North America, including Salishan, Wakashan and Chinookan languages, allow stop consonants and voiceless fricatives as syllables at the phonemic level, in even the most careful enunciation. An example is Chinook [ɬtʰpʰt͡ʃʰkʰtʰ] 'those two women are coming this way out of the water'. Syllabic obstruents used to be considered very rare, but surveys have shown that they are relatively common and might even be more common than syllabic liquids.[24]

Other examples:

- Nuxálk (Bella Coola)

- [ɬχʷtʰɬt͡sʰxʷ] 'you spat on me'

- [t͡sʼkʰtʰskʷʰt͡sʼ] 'he arrived'

- [xɬpʼχʷɬtʰɬpʰɬɬs] 'he had in his possession a bunchberry plant'[25]

- [sxs] 'seal blubber'

In Bagemihl's survey of previous analyses, he finds that the Bella Coola word /t͡sʼktskʷt͡sʼ/ 'he arrived' would have been parsed into 0, 2, 3, 5, or 6 syllables depending on which analysis is used. One analysis would consider all vowel and consonant segments as syllable nuclei, another would consider only a small subset (fricatives or sibilants) as nuclei candidates, and another would simply deny the existence of syllables completely. However, when working with recordings rather than transcriptions, the syllables can be obvious in such languages, and native speakers have strong intuitions as to what the syllables are.

This type of phenomenon has also been reported in Berber languages (such as Indlawn Tashlhiyt Berber), Mon–Khmer languages (such as Semai, Temiar, Khmu) and the Ōgami dialect of Miyako, a Ryukyuan language.[26]

- Indlawn Tashlhiyt Berber

- [tftktst tfktstt] 'you sprained it and then gave it'

- [rkkm] 'rot' (imperf.)[27][28]

- Semai

- [kckmrʔɛːc] 'short, fat arms'[29]

Languages with long sequences of obstruents pose a problem to several models of the syllable.[24]

Coda

[edit]The coda (also known as auslaut) comprises the consonant sounds of a syllable that follow the nucleus. The sequence of nucleus and coda is called a rime. Some syllables consist of only a nucleus, only an onset and a nucleus with no coda, or only a nucleus and coda with no onset.

The phonotactics of many languages forbid syllable codas. Examples are Swahili and Hawaiian. In others, codas are restricted to a small subset of the consonants that appear in onset position. At a phonemic level in Japanese, for example, a coda may only be a nasal (homorganic with any following consonant) or, in the middle of a word, gemination of the following consonant. (On a phonetic level, other codas occur due to elision of /i/ and /u/.) In other languages, nearly any consonant allowed as an onset is also allowed in the coda, even clusters of consonants. In English, for example, all onset consonants except /h/ are allowed as syllable codas.

If the coda consists of a consonant cluster, the sonority typically decreases from first to last, as in the English word help. This is called the sonority hierarchy (or sonority scale).[30] English onset and coda clusters are therefore different. The onset /str/ in strengths does not appear as a coda in any English word. However, some clusters do occur as both onsets and codas, such as /st/ in stardust. The sonority hierarchy is more strict in some languages and less strict in others.

Open and closed

[edit]A coda-less syllable of the form V, CV, CCV, etc. (V = vowel, C = consonant) is called an open syllable or free syllable, while a syllable that has a coda (VC, CVC, CVCC, etc.) is called a closed syllable or checked syllable. They have nothing to do with open and close vowels, but are defined according to the phoneme that ends the syllable: a vowel (open syllable) or a consonant (closed syllable). Almost all languages allow open syllables, but some, such as Hawaiian, do not have closed syllables.

When a syllable is not the last syllable in a word, the nucleus normally must be followed by two consonants in order for the syllable to be closed. This is because a single following consonant is typically considered the onset of the following syllable. For example, Spanish casar ("to marry") is composed of an open syllable followed by a closed syllable (ca-sar), whereas cansar "to get tired" is composed of two closed syllables (can-sar). When a geminate (double) consonant occurs, the syllable boundary occurs in the middle, e.g. Italian panna "cream" (pan-na); cf. Italian pane "bread" (pa-ne).

English words may consist of a single closed syllable, with nucleus denoted by ν, and coda denoted by κ:

- in: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /n/

- cup: ν = /ʌ/, κ = /p/

- tall: ν = /ɔː/, κ = /l/

- milk: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /lk/

- tints: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /nts/

- fifths: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /fθs/

- sixths: ν = /ɪ/, κ = /ksθs/

- twelfths: ν = /ɛ/, κ = /lfθs/

- strengths: ν = /ɛ/, κ = /ŋθs/

English words may also consist of a single open syllable, ending in a nucleus, without a coda:

- glue, ν = /uː/

- pie, ν = /aɪ/

- though, ν = /oʊ/

- boy, ν = /ɔɪ/

A list of examples of syllable codas in English is found at English phonology#Coda.

Null coda

[edit]Some languages forbid codas, so that all syllables are open. Examples are Hawaiian from the Austronesian family, and Swahili from the Atlantic–Congo family.

Suprasegmental features

[edit]The domain of suprasegmental features is a syllable (or some larger unit), but not a specific sound. That is to say, these features may affect more than a single segment, and possibly all segments of a syllable:

Sometimes syllable length is also counted as a suprasegmental feature; for example, in some Germanic languages, long vowels may only exist with short consonants and vice versa. However, syllables can be analyzed as compositions of long and short phonemes, as in Finnish and Japanese, where consonant gemination and vowel length are independent.

Tone

[edit]In most languages, the pitch or pitch contour in which a syllable is pronounced conveys shades of meaning such as emphasis or surprise, or distinguishes a statement from a question. In tonal languages, however, the pitch affects the basic lexical meaning (e.g. "cat" vs. "dog") or grammatical meaning (e.g. past vs. present). In some languages, only the pitch itself (e.g. high vs. low) has this effect, while in others, especially East Asian languages such as Chinese, Thai or Vietnamese, the shape or contour (e.g. level vs. rising vs. falling) also needs to be distinguished.

Accent

[edit]Syllable structure often interacts with stress or pitch accent. In Latin, for example, stress is regularly determined by syllable weight, a syllable counting as heavy if it has at least one of the following:

In each case, the syllable is considered to have two morae.

The first syllable of a word is the initial syllable and the last syllable is the final syllable.

In languages accented on one of the last three syllables, the last syllable is called the ultima, the next-to-last is called the penult, and the third syllable from the end is called the antepenult. These terms come from Latin ultima "last", paenultima "almost last", and antepaenultima "before almost last".

In Ancient Greek, there are three accent marks (acute, circumflex, and grave), and terms were used to describe words based on the position and type of accent. Some of these terms are used in the description of other languages.

| Placement of accent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antepenult | Penult | Ultima | ||

| Type of accent |

Circumflex | — | properispomenon | perispomenon |

| Acute | proparoxytone | paroxytone | oxytone | |

| Any | barytone | — | ||

History

[edit]Guilhem Molinier, a member of the Consistori del Gay Saber, which was the first literary academy in the world and held the Floral Games to award the best troubadour with the violeta d'aur top prize, gave a definition of the syllable in his Leys d'amor (1328–1337), a book aimed at regulating then-flourishing Occitan poetry:

Sillaba votz es literals. |

A syllable is the sound of several letters, |

Crosslinguistic patterns

[edit]CV is purported to be the universal syllable type that is found in all languages of the world, although two Australian languages, Arrernte and the Oykangand dialect of Kunjen, are possible exceptions.[31] CV is the first syllable type to be acquired by children, and if a language has only one type of a syllable, it is always CV (e. g. Hawaiian and Hua).[32]

Several asymmetries in onset and coda have been identified. All languages have syllables with onsets, but about 12.6% of languages in WALS do not allow codas.[33] The list of consonants allowed in the coda is usually smaller than the ones allowed in the onset (e. g. in Northern Germany, coda cannot have voiced consonants).[33] All combinations of onset and nucleus are usually allowed, but the coda consonant is sometimes restricted by the nucleus.[33]

Consonant clusters are more typical in onsets than in codas.[34]

Morphology

[edit]Complex syllables often occur as a result of morphological processes (e. g. the English word "texts" has an uncommon coda /kst-s/ after pluralisation).[24] Some models of the syllable even exclude morphologically complex syllables from their analysis.[24] At the same time, these clusters are acquired earlier by L1 speakers than the ones arising within a single morpheme, and are less reduced.[35]

See also

[edit]- English phonology#Phonotactics. Covers syllable structure in English.

- Line (poetry)

- List of the longest English words with one syllable

- Minor syllable

- Syllabary writing system

- Syllable (computing)

- Timing (linguistics)

- Vocalese

References

[edit]- ^ de Jong, Kenneth (2003). "Temporal constraints and characterising syllable structuring". In Local, John; Ogden, Richard; Temple, Rosalind (eds.). Phonetic Interpretation: Papers in Laboratory Phonology VI. Cambridge University Press. p. 254. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511486425.015. ISBN 978-0-521-82402-6.

- ^ a b Easterday 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Easterday 2019, p. 1.

- ^ Easterday 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Hooker, J. T. (1990). "Introduction". Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet. University of California Press; British Museum. p. 8. ISBN 0-520-07431-9.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "syllable". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ λαμβάνω. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Smyth 1920, §523: present stems formed by suffixes containing ν

- ^ International Phonetic Association (December 1989). "Report on the 1989 Kiel Convention: International Phonetic Association". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 19 (2). Cambridge University Press: 75–76. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003868. S2CID 249412330.

- ^ a b c Easterday 2019, p. 10.

- ^ More generally, the letter φ indicates a prosodic foot of two syllables

- ^ More generally, the letter μ indicates a mora

- ^ For discussion of the theoretical existence of the syllable see "CUNY Conference on the Syllable". CUNY Phonology Forum. CUNY Graduate Center. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Bermúdez-Otero, Ricardo (2015). "The life cycle of High Vowel Deletion in Old English: from prosody to stratification and loss" (PDF). p. 2.

- ^ Fikkert, Paula; Dresher, Elan; Lahiri, Aditi (2006). "Chapter 6, Prosodic Preferences: From Old English to Early Modern English". The Handbook of the History of English (PDF). pp. 134–135. ISBN 9780470757048.

- ^ Feng, Shengli (2003). A Prosodic Grammar of Chinese. University of Kansas. p. 3.

- ^ a b Hultzén, Lee S. (1965). "Consonant Clusters in English". American Speech. 40 (1): 5–19. doi:10.2307/454173. ISSN 0003-1283. JSTOR 454173.

- ^ Shibatani, Masayoshi (1987). "Japanese". In Bernard Comrie (ed.). The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 855–80. ISBN 0-19-520521-9.

- ^ Wells, John C. (1990). "Syllabification and allophony". In Ramsaran, Susan (ed.). Studies in the pronunciation of English : a commemorative volume in honour of A.C. Gimson. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 76–86. ISBN 9781138918658.

- ^ Easterday 2019, p. 9.

- ^ Breen, Gavan; Pensalfini, Rob (1999). "Arrernte: A Language with No Syllable Onsets" (PDF). Linguistic Inquiry. 30 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1162/002438999553940. JSTOR 4179048. S2CID 57564955.

- ^ Wiese, Richard (2000). Phonology of German. Oxford University Press. pp. 58–61. ISBN 9780198299509.

- ^ Easterday 2019, pp. 10−11.

- ^ a b c d Easterday 2019, p. 11.

- ^ Bagemihl 1991, pp. 589, 593, 627

- ^ Pellard, Thomas (2010). "Ōgami (Miyako Ryukyuan)". In Shimoji, Michinori (ed.). An introduction to Ryukyuan languages (PDF). Fuchū, Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. pp. 113–166. ISBN 978-4-86337-072-2. Retrieved 21 June 2022. HAL hal-00529598

- ^ Dell & Elmedlaoui 1985

- ^ Dell & Elmedlaoui 1988

- ^ Sloan 1988

- ^ Harrington, Jonathan; Cox, Felicity (August 2014). "Syllable and foot: The syllable and phonotactic constraints". Department of Linguistics. Macquarie University. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Easterday 2019, pp. 4−5.

- ^ Easterday 2019, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Easterday 2019, p. 6.

- ^ Easterday 2019, p. 6–7.

- ^ Easterday 2019, p. 12.

Sources and recommended reading

[edit]- Bagemihl, Bruce (1991). "Syllable structure in Bella Coola". Linguistic Inquiry. 22 (4): 589–646. JSTOR 4178744.

- Clements, George N.; Keyser, Samuel J. (1983). CV phonology: a generative theory of the syllable. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs. Vol. 9. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press. ISBN 9780262030984.

- Dell, François; Elmedlaoui, Mohamed (1985). "Syllabic consonants and syllabification in Imdlawn Tashlhiyt Berber". Journal of African Languages and Linguistics. 7 (2): 105–130. doi:10.1515/jall.1985.7.2.105. S2CID 29304770.

- Dell, François; Elmedlaoui, Mohamed (1988). "Syllabic consonants in Berber: Some new evidence". Journal of African Languages and Linguistics. 10: 1–17. doi:10.1515/jall.1988.10.1.1. S2CID 144470527.

- Easterday, Shelece (2019). Highly complex syllable structure: A typological and diachronic study. Language Science Press. ISBN 978-3-96110-194-8. Retrieved 2025-03-10.

- Ladefoged, Peter (2001). A course in phonetics (4th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers. ISBN 0-15-507319-2.

- Sloan, Kerry (1988). "Bare-Consonant Reduplication: Implications for a Prosodic Theory of Reduplication". In Borer, Hagit (ed.). The Proceedings of the Seventh West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. WCCFL 7. Irvine, CA: University of Chicago Press. pp. 319–330. ISBN 9780937073407.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). A Greek Grammar for Colleges. American Book Company. Retrieved 1 January 2014 – via CCEL.

Syllable

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Definition

Etymology

The term "syllable" entered English through Middle English syllable, borrowed from Anglo-Norman sillable and Old French sillebe, ultimately deriving from Latin syllaba, which translates to "a letter" or "the smallest part of a word." This Latin form stems directly from Ancient Greek συλλαβή (sullabḗ), literally meaning "a gathering of letters" or "that which is held together," formed by compounding σύν (sýn, "together") with λαμβάνω (lambánō, "to take" or "to seize").[8][9] In parallel to this Greco-Latin lineage, ancient Indian linguistics developed the concept of the syllable through the Sanskrit term akṣara, meaning "imperishable" or "indestructible," denoting the atomic units of speech that form the foundation of phonetic and phonological analysis. Articulated in Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī (circa 4th century BCE), akṣara encompassed vowels and consonant-vowel clusters as stable, eternal elements of language, influencing early phonological thought and later comparative studies in Indo-European linguistics.[10] The evolution of the term in European linguistics traces back to classical antiquity, where Greek grammarians like Dionysius Thrax (2nd century BCE) defined the syllable as a prosodic unit composed of a vowel and optional consonants, primarily for metrical and accentual purposes in poetry.[11] By the 16th century, Renaissance humanists revived this framework in vernacular grammars, such as William Lily's A Short Introduction of Grammar (1540), integrating the syllable into pedagogical tools for pronunciation, spelling, and classical imitation across languages like Latin, Greek, and emerging national tongues. In the 19th century, amid the rise of historical-comparative philology, scholars such as Franz Bopp and August Schleicher reconceptualized the syllable as a phonological primitive—a core structural element driving sound changes and language reconstruction in Indo-European studies—shifting its emphasis from mere prosodic timing to a fundamental building block of sound systems.[12] This transformation marked a key etymological shift, aligning the term with modern phonology's focus on universal sound organization rather than classical metrics alone.Definition

In phonology, a syllable is defined as the smallest unit of speech organization, consisting of a nucleus—typically a vowel or vowel-like element—around which optional consonants are grouped as an onset preceding the nucleus and a coda following it.[1] This structure captures the hierarchical grouping of sounds in spoken language, where the nucleus forms the core sonority peak essential to syllablehood.[1] Unlike a phoneme, which is the minimal contrastive unit of sound that distinguishes meaning (such as /p/ versus /b/ in "pat" and "bat"), a syllable functions as a prosodic unit that organizes phonemes into larger rhythmic and structural patterns across words and utterances.[1] Phonemes operate at the segmental level to convey lexical distinctions, whereas syllables impose suprasegmental properties like stress, tone, and timing, enabling the phonological hierarchy observed in languages worldwide.[1] Criteria for identifying syllables often rely on the sonority principle, where a syllable centers on a peak of sonority—the relative loudness or resonance of sounds—with sonority rising toward the nucleus from the onset and falling toward the coda, as in the hierarchy vowels > glides > liquids > nasals > obstruents.[1] In moraic theory, syllables are further analyzed as timing units composed of moras, the basic quanta of phonological weight, where a short vowel contributes one mora and a long vowel or heavy syllable (with a coda) contributes two, accounting for rhythmic isochrony in languages like Japanese.[13] The reality of syllables as primitive phonological units remains debated, with strong evidence from phonotactics—restrictions on sound sequences that align with syllabic boundaries, such as English disfavoring coda clusters like /tl/—supporting their necessity for explaining linguistic patterns.[1] However, skeptics propose that syllables may be epiphenomenal or dispensable, arguing that many phonotactic effects can be captured by syllable-independent, string-based conditions on positional markedness, without invoking syllabic constituents.[14]Representation

Transcription

In phonetic transcription, syllables are delineated using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), where a dot (.) serves as the standard symbol to indicate syllabic boundaries, facilitating precise analysis of phonological structure across languages. For instance, the English word "cater" is transcribed as /kæt.ə/, separating the consonant cluster and vowel nucleus into distinct syllables. This convention, established by the International Phonetic Association, ensures clarity in representing syllable divisions for comparative linguistic studies. Syllabification practices differ between broad and narrow transcriptions: broad transcriptions provide a general overview of syllable structure without fine-grained details, while narrow transcriptions capture variations such as allophonic realizations or suprasegmental features like tone. In narrow transcription, suprasegmentals are integrated, as seen in Mandarin Chinese where syllables often carry lexical tones marked above vowels, such as /ma¹/ for "mother" versus /ma⁴/ for "scold," highlighting how tone influences syllabic identity. Broad transcriptions, by contrast, might omit these for simplicity, focusing solely on segmental content. This distinction aids in pedagogical and analytical contexts, balancing accessibility with phonetic accuracy. Transcribing ambiguous cases poses challenges, particularly in connected speech where resyllabification occurs, shifting boundaries across word edges and complicating static representations. In English, the phrase "hand bag" may resyllabify in fluent speech from /hænd.bæɡ/ to /hæn.dbæɡ/, with the /d/ moving to the onset of the following syllable, requiring contextual notation in narrow transcription to reflect prosodic flow. Similarly, in French, liaison phenomena like "les amis" (/le.z‿a.mi/) demonstrate resyllabification where a latent consonant integrates into the next syllable's onset, often marked with a tie bar (‿) to indicate elision and boundary adjustment. These dynamic processes underscore the limitations of linear transcription in capturing real-time phonology, often necessitating supplementary annotations or spectrographic analysis. Examples from diverse languages illustrate these conventions: in English, "strengths" is broadly transcribed as /streŋθs/ but narrowly as /strɛŋkθs/ to show epenthetic elements affecting syllabification; in French, "Paris" appears as /pa.ʁi/ with clear vowel-centered syllables; and in Mandarin, disyllabic words like "shūfáng" (book room) are rendered as /ʂu¹.fa²ŋ/, incorporating tones and aspirated onsets to define each syllable unit. Such representations emphasize syllables as core units for phonological comparison, revealing language-specific patterns in segmentation.Notation Systems

Syllabaries represent a class of writing systems in which individual symbols correspond to syllables, typically following a consonant-vowel (CV) structure, facilitating the notation of syllabic units directly in scripts used for languages with relatively simple syllable inventories.[15] In Japanese, the kana systems—hiragana and katakana—each consist of about 46 basic characters that denote morae, which often align with syllables, enabling phonetic representation without alphabetic segmentation. Similarly, the Cherokee syllabary, developed by Sequoyah in the early 19th century, employs 85 symbols to encode Cherokee syllables, allowing rapid literacy acquisition as each glyph maps straightforwardly to a spoken syllable.[16] In linguistic analysis, syllable boundaries are commonly notated using hyphens, dots, or spaces to delineate structure, particularly in phonological representations and theoretical frameworks. For instance, in Optimality Theory tableaux, candidate forms often employ dots (.) to mark syllable divisions, such as in evaluating constraints on onset or coda formation across potential parses like /at.las/ versus /a.tlas/.[17] This convention aids in visualizing constraint interactions without relying on phonetic details, complementing broader transcription methods.[18] Computational notations for syllables appear in speech synthesis systems, where markup languages control prosody and emphasis at the syllabic level to enhance naturalness. The Speech Synthesis Markup Language (SSML), standardized by the W3C, includes thetag allows explicit specification of syllable stress markers for precise pronunciation control.[19] For example, in SSML, stress can be denoted within phonemic alphabets to place primary or secondary emphasis on specific syllables, as supported in APIs like Google Cloud Text-to-Speech.[20]

Phonological Structure

Onset

In phonology, the onset of a syllable comprises the optional sequence of one or more consonants that immediately precede the nucleus, the core vocalic element of the syllable.[23] For example, in the English word "street" /striːt/, the onset is the cluster /str/, consisting of the fricative /s/, the stop /t/, and the approximant /r/.[24] Cross-linguistically, onsets are preferred over onsetless syllables, a tendency known as the Onset Principle, though many languages permit syllables without onsets, particularly those beginning with vowels.[23] Onset clusters are governed by the Sonority Sequencing Principle (SSP), which posits that sonority— a measure of acoustic prominence increasing from obstruents (stops and fricatives) to sonorants (nasals, liquids, glides) to vowels—must generally rise from the onset toward the nucleus.[24] In languages like English, this results in permissible clusters such as /pl/ in "play," where the stop /p/ (low sonority) precedes the liquid /l/ (higher sonority).[25] English allows complex onsets up to three consonants (CCC), typically structured as an initial sibilant /s/ followed by a stop and a liquid or glide, as in /spl/ of "splash," though such clusters may deviate from strict rising sonority due to language-specific allowances for obstruent sequences.[26] Syllables may have a null (empty) onset when they begin with a vowel, as in English "apple" /ˈæp.əl/, where the first syllable lacks preceding consonants.[27] In some languages, such as French, vowel-initial syllables can trigger liaison, where a consonant from a preceding word fills the onset position, e.g., /lə.z.am.i/ for "les amis."[28] Phonotactic constraints further restrict possible onsets based on language-specific rules, prohibiting certain combinations even if they align with sonority. In English, for instance, clusters like *tl or *dl are illicit in onsets, as in the non-occurring *tlight, due to restrictions on stop-liquid sequences involving alveolar stops and lateral approximants.[28] These constraints reflect universal tendencies modulated by historical and articulatory factors, ensuring only well-formed onsets occur within syllables.[29]Nucleus

The nucleus constitutes the obligatory core of the syllable, serving as its sonority peak and providing the primary prominence through maximal acoustic intensity and resonance.[1] This peak is typically realized as a vowel, which occupies the highest position on the sonority scale—a hierarchical ranking of speech sounds based on their relative loudness and openness of articulation.[30] The scale places vowels at the apex, followed by glides, liquids, nasals, and obstruents in descending order of sonority (vowel > glide > liquid > nasal > obstruent), ensuring that the nucleus stands out as the most resonant element and anchors the syllable's perceptual structure.[25] This centrality explains why every syllable must contain a nucleus: without it, the syllable lacks a perceptible peak, rendering the unit unstable or ill-formed in phonological theory.[30] While vowels predominate, the nucleus may also consist of syllabic consonants in certain languages or contexts, where a consonant assumes a vowel-like role due to its sufficient sonority and lack of an adjacent vowel.[1] For instance, in English, the dark lateral /l̩/ functions as a syllabic nucleus in words like "bottle" (/ˈbɑt.l̩/), where it replaces a full vowel in the second syllable.[31] Articulatory evidence shows that syllabic /l/ involves a prolonged lateral gesture with vocalic lowering of the tongue body, mimicking vowel production, while acoustic analysis reveals clear formant transitions (e.g., F1 around 500–700 Hz and F2 around 1200–1500 Hz) that parallel those of mid vowels, confirming its nuclear status despite consonantal articulation.[31] Such cases highlight the nucleus's flexibility, extending to other syllabic sonorants like /n̩/ or /m̩/ in languages such as Slovak or Polish, where sonority thresholds allow consonants to peak without vowel support.[32] Nuclei can also be complex, incorporating multiple vocalic elements within a single peak to enhance sonority or express phonological contrasts.[33] Diphthongs, such as /aɪ/ in English "eye" (/aɪ/), exemplify this: the glide from a low central vowel to a high front one forms a unified nucleus occupying two timing slots, treated as a single sonorous unit rather than separate vowels.[33] This configuration maintains the syllable's peak integrity while allowing internal movement, as evidenced by consistent stress placement and moraic weight in languages like English.[33] The onset and coda, comprising pre- and post-nuclear consonants, respectively, frame this peak without altering its obligatory sonorous dominance.[1]Coda

The coda consists of the optional consonants or consonant cluster that immediately follow the nucleus in a syllable, providing closure to the syllabic peak and influencing its phonetic realization.[23] In languages like English, the coda may include one or more post-nuclear consonants, such as the velar nasal-stop sequence /ŋk/ in the word think (/θɪŋk/), where these segments trail the vowel nucleus /ɪ/.[34] Syllables lacking a coda are termed open, ending in a vowel and typically allowing for freer vowel quality or length, as in English go (/goʊ/), a CV syllable structure.[24] In contrast, syllables with a coda are closed, featuring a final consonant that often shortens the preceding vowel, exemplified by got (/gɑt/), where /t/ forms the coda.[35] This distinction affects prosodic patterns across languages, with closed syllables contributing to greater syllabic weight in some phonological systems.[34] Coda clusters, when present, are subject to phonotactic constraints that generally enforce a falling sonority profile, where sonority decreases from the nucleus outward to facilitate perceptual clarity.[36] English permits complex triconsonantal codas like /sts/ in tests (/tɛsts/), adhering to sonority sequencing despite the cluster's intricacy, though such formations are limited by language-specific rules prohibiting certain combinations.[37] In languages with strict open syllable structures, codas are null, meaning no consonants follow the nucleus; Hawaiian exemplifies this, restricting syllables to V or CV forms without any coda elements.[38] This prohibition shapes Hawaiian phonology, eliminating closed syllables and favoring vowel sequences across morpheme boundaries.[39] Codas may interact with adjacent onsets during resyllabification processes in connected speech.[23]Rime

In phonology, the rime (also spelled rhyme) constitutes the core subunit of a syllable, comprising the nucleus and the coda. This structure groups the syllabic peak—typically a vowel or diphthong—with any following consonants, forming a tight-knit unit that contrasts with the optional onset. For instance, in the English monosyllabic word "out" transcribed as /aʊt/, the rime is /aʊt/, where /aʊ/ serves as the nucleus and /t/ as the coda.[5] The rime's internal cohesion is evident in phonological processes that treat it as indivisible, such as certain assimilation rules where coda consonants influence the nucleus quality.[29] The rime plays a central role in rhyming patterns, particularly in poetry and verse, where linguistic rhyme occurs when two or more words share an identical rime while differing in their onsets. This shared rime creates auditory parallelism, enhancing memorability and rhythmic flow; for example, the words "out" and "shout" rhyme because both have the rime /aʊt/, despite differing onsets /Ø/ and /ʃ/. Such patterns underpin traditional poetic forms across languages, from English sonnets to Mandarin tonal verses, underscoring the rime's perceptual salience in sound organization.[40] Evidence for the rime as a distinct constituent emerges from language games and speech errors that manipulate syllables by isolating the onset from the rime. In Pig Latin, a common English word game, the onset is typically detached and affixed to the end of the word, with a filler like "ay" added to the remaining rime; thus, "cat" (/kæt/) becomes "atcay," preserving the rime /æt/ intact. Similar rearrangements in other games, such as spoonerisms, often swap onsets while keeping rimes stable, supporting the hierarchical structure where the rime functions as a cohesive block.[29][41] Although the nucleus and coda are individually analyzed as the rime's components, some phonological frameworks propose an alternative "body" constituent encompassing the onset and nucleus, with the coda treated separately; however, the standard rime model predominates in generative phonology for its explanatory power in rhyming and prosodic grouping.Syllabification

Principles

Syllabification involves dividing a sequence of sounds into syllables according to phonological rules that structure words into onset, nucleus, and coda components.[42] A key principle is the Maximal Onset Principle, which prioritizes assigning as many consonants as possible to the onset of a syllable rather than the coda of the preceding one, provided the resulting cluster is permissible in the language.[42] For instance, in English, the word "extra" is syllabified as /ɛk.strə/, where /str/ forms the maximal onset of the second syllable.[43] Another foundational approach is sonority-based syllabification, which relies on the Sonority Sequencing Principle to organize sounds within syllables.[44] According to this principle, sonority rises from the syllable margins toward the nucleus (the sonority peak, typically a vowel) and falls afterward, with sonority troughs marking the edges of syllables.[44] Language-specific rules further refine these principles; for example, English tends to favor divisions like VC.CV (closed syllable followed by open) over CV.CVC when consonant clusters allow maximal onsets, as seen in words like "happen" (/hæp.ən/).[42] Algorithmic steps for syllabification generally proceed by first identifying and assigning syllable nodes to nuclei (syllabic sounds like vowels), then attaching consonants to onsets of following syllables per the Maximal Onset Principle, and finally assigning any remaining consonants to codas of preceding syllables.[42]Ambisyllabicity

Ambisyllabicity refers to the phonological phenomenon in which a consonant is simultaneously affiliated with two adjacent syllables, functioning as the coda of the preceding syllable and the onset of the following one.[45] This dual membership arises in word-medial positions, particularly after a short stressed vowel followed by an unstressed vowel, as in English words like apple (/ˈæp.əl/), where the /p/ exhibits ambisyllabic properties, or bottle (/ˈbɑt̬.əl/), where the /t/ is shared.[46] Evidence for ambisyllabicity in English comes from phonological processes that treat medial consonants differently based on their potential dual role. For instance, in American English, intervocalic flapping applies to /t/ and /d/ in words like butter (/ˈbʌt̬ɚ/), where the consonant is ambisyllabic, producing a flap [ɾ], but not in button (/ˈbʌt.n̩/), where it functions solely as a coda.[47] Experimental studies further support this, showing that speakers classify consonants as ambisyllabic more frequently when the preceding vowel is lax or stressed and the consonant is a sonorant, as analyzed in 581 bisyllabic words like habit (/ˈhæb.ɪt/), where /b/ was deemed ambisyllabic in participant divisions.[48] Articulatory correlates, such as increased duration and tension in glides and liquids, also indicate ambisyllabic status in forms like feeling.[49] Theories of ambisyllabicity contrast linear and nonlinear approaches. Linear models represent it through gemination, where the consonant is duplicated or linked across syllables, as proposed in analyses of English flapping and Danish consonant gradation, treating ambisyllabic consonants as geminates to account for rules like stød association in words such as laba (/ˈlaː.bɑ/).[47] Nonlinear theories, influential since Kahn's 1976 work on syllable-based generalizations, employ branching structures in autosegmental phonology, allowing a single consonant to associate with both a coda and an onset position, facilitating constraints in Optimality Theory for heavy syllables (e.g., short vowel + coda).[50] In contrast, Government Phonology rejects ambisyllabicity, prohibiting improper bracketing and instead deriving similar effects through strict constituent government relations between skeletal positions, as in Harris's 1994 framework.[51] Cross-linguistically, ambisyllabicity is prevalent in Germanic languages but rare in Romance ones. In Germanic varieties like English, Danish, and German, it explains vowel length alternations and voicing patterns, such as fricative voicing in West Germanic dialects (e.g., Dutch water with ambisyllabic /t/), where medial consonants after short vowels share syllabic roles.[52] Danish provides clear evidence through mixed rule application in monomorphemic forms like kapa, supporting geminate-like representations.[47] Romance languages, however, typically exhibit clearer syllable boundaries with less dual affiliation; for example, Spanish shows incomplete resyllabification across morphemes but avoids word-internal ambisyllabicity, as in habla (/ˈaβ.la/), where /b/ aligns strictly as an onset without coda sharing.[53] This typological difference aligns with Germanic tolerance for complex onsets and Romance preference for sonority-based divisions.[54]Special Configurations

In syllable structure, null onsets occur when a syllable begins with a vowel without a preceding consonant, as seen in the first syllable of the English word "approach" pronounced as [əˈproʊtʃ], where [ə] lacks both an onset and a coda. Null codas similarly appear in open syllables ending in a vowel, such as the final syllable in "sofa" [ˈsoʊ.fə], which has no coda consonant. These configurations are common in languages adhering to the Sonority Sequencing Principle, where vowels form the peak without obligatory marginal consonants, though some phonological theories posit empty consonantal slots to maintain universal templates. In certain dialects, vowel-initial words trigger prothetic sounds to fill potential null onsets; for instance, in some Romance varieties like Asturian Spanish, a prothetic /e/ may insert before initial /s/ + consonant clusters in loanwords, effectively creating an onset where none existed etymologically, as in adaptations resembling "español" from Latin sources. This process avoids hiatus or eases articulation in casual speech, though it varies by dialect and is not universal across V-initial forms. Consonant nuclei, or syllabic consonants, arise when a sonorant consonant—typically /l/, /r/, /m/, or /n/—functions as the syllable's peak due to the absence of a vowel, often in unstressed positions following obstruents. Conditions for syllabicity generally require the consonant to exhibit sufficient sonority to peak the syllable, be unlicensed by a preceding vowel (e.g., in coda positions without epenthesis), and occur in languages permitting non-vocalic nuclei, such as English in words like "bottle" [ˈbɑt.l̩] or "button" [ˈbʌt.n̩]. In Slavic languages, while some like Czech permit syllabic consonants, as in "prst" [pr̝st] (finger) with a syllabic /r/, analyses of Polish highlight that trapped sonorants in complex clusters are typically realized with a reduced vowel rather than a true consonantal nucleus, underscoring constraints against pure syllabic consonants in modern Polish phonology.[55] These structures contrast with standard vocalic nuclei and often involve resyllabification or schwa insertion to resolve complexity. Extreme onset and coda clusters push syllable margins beyond typical biconsonantal limits, as in Georgian, where word-initial onsets can reach three or more consonants, such as the CCC sequence in "mtvrtneli" (vintner), comprising /m-t-v/ without intervening vowels. Georgian permits up to eight-consonant onsets in derived forms, with sonority profiles allowing rising or flat sequences (e.g., obstruent-sonorant-obstruent), facilitated by aggressive vowel reduction in the language's historical morphology. Coda clusters similarly extend to four or more consonants in some Caucasian languages, though Georgian codas are generally simpler, maxing at two or three, reflecting typological preferences for onset complexity over coda in ejective-heavy systems. Such extremes challenge linear models of syllable structure, often analyzed as single-branching onsets in optimality-theoretic frameworks. Resyllabification across word boundaries alters null onsets by reassigning a coda consonant from one syllable to become the onset of the next, prominently in French liaison. For example, in "petit ami" (little friend), the latent /t/ of "petit" [pə.ti] resyllabifies to form [pə.ti.t‿a.mi], creating a new CV onset for "ami" and avoiding a null onset after the vowel. This process is obligatory in certain syntactic contexts, such as between determiners and nouns, and involves both phonetic realization of the consonant and perceptual adjustment by listeners to the shifted boundary. Relatedly, ambisyllabicity may overlap in such cases, where a consonant holds dual affiliation briefly during the transition.Suprasegmental Features

Tone

In tonal languages, tone functions as a suprasegmental feature that employs pitch variations—either steady levels or dynamic contours—to differentiate lexical items or grammatical categories, with these pitch distinctions fundamentally linked to syllables as the domain of realization.[56] For instance, in Mandarin Chinese, a Sino-Tibetan language, each syllable carries one of four primary tones: a high-level tone (e.g., mā 'mother'), a rising tone (e.g., má 'hemp'), a low-dipping tone (e.g., mǎ 'horse'), or a high-falling tone (e.g., mà 'scold'), where altering the tone can change the word's meaning entirely.[57] These tones are contrastive at the lexical level, highlighting how pitch serves as a phonemic property in approximately 40-60% of the world's languages.[56] The syllable, often specifically its sonorous nucleus, acts as the primary tone-bearing unit (TBU) in the majority of tonal systems, supporting associations with high or low pitch registers that define the tone's perceptual quality.[58] In autosegmental phonology, tones are represented on a separate tier linked to these TBUs via association lines, allowing a single tone to potentially spread across multiple syllables if needed to ensure universal association.[59] The nucleus provides the stable anchor for tone, as its vowel or syllabic consonant sustains the pitch trajectory throughout the syllable's duration.[60] Contour tones, such as rising or falling patterns, represent more complex pitch movements over the syllable and are frequently decomposed phonologically into sequences of simpler level tones, like a low followed by a high for a rising contour.[61] This decomposition facilitates analysis in frameworks like autosegmental-metrical theory, where contours arise from sequential tone associations rather than unitary features.[56] Tonal phonology encompasses dynamic processes that operate on syllable-associated tones, including spreading, where a tone from a marked syllable links to adjacent toneless ones to fill gaps in the tonal melody—for example, in Bantu languages like Chishona, a high tone may spread rightward across two syllables in verbal stems.[62] Tone sandhi rules further modify these associations contextually, often to resolve phonetically disfavored sequences; in Mandarin, when two third-tone syllables adjoin (e.g., nǐ hǎo), the first shifts to a second-tone realization (ní hǎo) to avoid a low-dipping contour followed by another low, a change triggered by prosodic structure and perceptual ease.[63] Such rules exemplify how tonal systems maintain harmony across syllables while preserving contrastive distinctions.[64]Stress and Accent

Stress refers to the relative prominence given to a particular syllable within a word, often realized through increased duration, intensity, and pitch height, contributing to the rhythmic structure of languages like English.[65] In English, stress typically follows trochaic patterns, where prominence alternates in a left-to-right fashion, forming binary feet with a strong-weak syllable structure, as proposed in metrical phonology.[66] This rhythmic organization avoids clashes between adjacent stressed syllables, ensuring a balanced prosodic flow.[67] Accent, in contrast, often involves lexical specification of prominence, particularly in pitch-accent systems where high pitch marks the accented syllable. In Japanese, accent is moraic, with the pitch falling after the accented mora, distinguishing words like hashi 'bridge' (high-low on first mora) from hashi 'edge' (low-high-low).[68] This system relies on the mora as the unit of timing, where each mora receives roughly equal duration, and accent location is lexically determined rather than purely rhythmic.[69] Syllable weight plays a crucial role in determining stress placement, with heavy syllables—those containing a bimoraic rhyme, such as CVV or CVC—attracting prominence over light syllables (CV).[70] In weight-sensitive systems like Latin or certain dialects of English, stress favors the penultimate heavy syllable, reflecting a universal tendency where longer or more sonorous rimes draw rhythmic emphasis.[71] This sensitivity integrates phonetic duration with phonological rules, as heavier syllables inherently sound more prominent.[72] Stress rules operate at both word and phrase levels, with word stress assigned lexically or morphologically, while phrase stress highlights content words in sentences, reducing function words.[73] In unstressed syllables, vowels often undergo reduction, centralizing to a schwa /ə/ sound, as in English photograph (/ˈfoʊ.tə.ɡræf/), which minimizes articulatory effort and enhances rhythmic contrast.[74] In pitch-accent languages like Japanese, stress-like effects can interact with tone through pitch prominence on accented moras.[75]Historical Development

Ancient and Medieval Views

In ancient Greek linguistic thought, the syllable was primarily understood as a combination of letters forming a phonetic unit. Aristotle conceptualized the syllable as "a non-significant sound, composed of a mute [consonant] and a vowel," categorizing it among non-significant elements of speech distinct from meaningful words or propositions.[76] This definition emphasized the syllable's role as a basic building block of sound, excluding isolated vowels which he treated as inherently long but not as prototypical syllables.[77] Dionysius Thrax, in his influential Techne Grammatike (Art of Grammar), defined the syllable as the combination of a vowel with a consonant or consonants; a single vowel is considered improperly a syllable.[11] He highlighted their function in prosody where quantity—long or short—determined metrical patterns in poetry, such as in epic verse where long syllables (by nature or position) contrasted with short ones to create rhythmic feet.[78] The Sanskrit grammatical tradition, as codified by Pāṇini in the Aṣṭādhyāyī (circa 5th–4th century BCE), integrated the syllable (akṣara or ekāc) as a core phonological unit essential for metrics (chandas). Pāṇini defined ekāc as a segment containing a single vowel (ac), serving as the fundamental element for generating words and verses, with rules specifying how consonants attach to vowels to form syllables.[79] In poetic metrics, syllables were distinguished by duration: short (laghu, one mātrā or time unit, typically a short vowel) and long (guru, two mātrā, either a long vowel or short vowel followed by a consonant), enabling complex patterns in Vedic hymns and classical kāvya.[80] Pāṇini's formal rules, such as those in the Chandas-sūtra sections, ensured precise syllabification for rhythmic scansion, prioritizing the syllable's role in maintaining metrical integrity over semantic considerations.[81] During the medieval period, Arabic scholars advanced syllable theory within poetics and linguistics, building on Greek foundations while adapting to Semitic structures. Al-Khalīl ibn Aḥmad al-Farāhīdī (d. 791 CE) founded the science of ʿarūḍ, analyzing poetic meter through quantitative prosody based on short and long syllables, where long syllables could be extended by diphthongs or following consonants, creating balanced patterns for auditory pleasure and structural coherence in poetry.[82] These distinctions, rooted in quantitative prosody, influenced medieval Latin grammarians through translations, as they incorporated similar notions of syllable length into analyses of Latin verse, emphasizing positio (position-induced length) and natura (inherent length) for metrical composition in hymns and epic poetry.[83] This cross-cultural exchange reinforced the syllable's centrality in metrics, where long and short distinctions governed poetic form across traditions, from Arabic qaṣīda to Latin hexameter.[83]Modern Linguistic Theories

The late 19th-century Neogrammarian school, led by linguists such as Hermann Osthoff and Karl Brugmann, conceptualized the syllable as the fundamental phonotactic domain regulating regular sound changes, where phonetic conditioning operates exceptionlessly within syllable-internal positions like onset, nucleus, and coda.[84] This approach emphasized the syllable's role in defining permissible sound sequences and transitions, treating it as a mechanistic unit in speech production that constrains phonetic evolution across languages. In the structuralist tradition of the early 20th century, Nikolai Trubetzkoy advanced the syllable's prosodic significance in his seminal Grundzüge der Phonologie (1939), portraying it as a suprasegmental unit that organizes phonological oppositions and bears features such as stress, tone, and intonation beyond individual segments.[85] Trubetzkoy argued that the syllable functions as a structural bundle of successive phonemes, with boundaries determined by sonority hierarchies, thereby integrating it into the broader phonological system as a domain for prosodic analysis.[86] Generative phonology marked a shift toward formal representations, with Noam Chomsky and Morris Halle's The Sound Pattern of English (1968) introducing the syllable as an explicit constituent in phonological derivations, enabling rules for stress assignment and segmental interactions within a hierarchical framework.[87] This model treated the syllable as a necessary structural layer to capture generalizations about vowel length, consonant clusters, and prosodic well-formedness, influencing subsequent developments in rule-based phonology. Following the 1980s, moraic theory, as proposed by Larry Hyman in A Theory of Phonological Weight (1985), redefined the syllable in terms of timing units called moras, where syllable weight emerges from linear associations of segments to moras rather than branching trees, accounting for phenomena like compensatory lengthening and stress sensitivity.[88] Concurrently, Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky, 1993) modeled syllabification through ranked, violable constraints—such as ONSET (favoring syllable-initial consonants), NOCODA (prohibiting codas), and *COMPLEX (limiting cluster size)—where the optimal output resolves conflicts via constraint interaction.[89] These frameworks prioritized universal principles over language-specific rules, enhancing cross-linguistic explanations of syllable structure.[90] In the 2020s, ongoing debates center on the syllable's psychological reality, bolstered by psycholinguistic evidence from tasks like nonword repetition and implicit learning, which demonstrate speakers' subconscious access to syllabic units in production and perception, as seen in studies of children's syllable boundary detection.[91] Such findings affirm the syllable's cognitive salience, challenging purely abstract phonological models and supporting hybrid representations that incorporate processing constraints.[92]Cross-Linguistic Variation

Common Patterns

The consonant-vowel (CV) template represents the most basic and universal syllable structure, occurring in every known language as the core or permitted pattern. This simplicity aligns with typological universals proposed in early phonological theory, where CV is posited as the unmarked syllable type acquired first by children and preserved across linguistic evolution. In a global sample of 486 languages, CV syllables form the foundation for all syllable structures, with only 12.5% of languages restricting themselves exclusively to CV without additional complexity.[7] Across languages, simple onsets and codas—typically consisting of a single consonant—are predominant, especially in moderately complex syllable systems that characterize 56.5% of sampled languages. These systems permit CV and CVC patterns or restricted CCV onsets (e.g., involving liquids or glides), but avoid dense clusters, reflecting a preference for sonority-based sequencing where consonants rise in sonority toward the vowel nucleus. This predominance of single-consonant margins contributes to the overall accessibility of phonological parsing in everyday speech.[7] Open syllables, lacking a coda and thus ending in a vowel, are especially frequent in vowel-heavy languages such as those of the Polynesian family, where the syllable template is strictly (C)V or CV with no closed forms. For instance, Hawaiian and Māori exhibit only open syllables of the form (C)V(V), prohibiting codas entirely and emphasizing vocalic prominence in prosody. This pattern underscores a typological tendency in Austronesian languages toward syllable openness, facilitating rhythmic flow and vowel harmony.[5] Statistical analyses from databases like the UCLA Phonological Segment Inventory Database (UPSID), covering 451 languages, reveal average syllable complexity as moderate, with most languages exhibiting a balance between CV simplicity and limited additions like single-coda CVC. Complexity indices, which score onsets, nuclei, and codas (ranging from 1 for pure CV to 8 for highly clustered forms like English), show a mean around 4-5, correlating positively with consonant inventory size but favoring uncomplicated margins in the majority of cases. These tendencies highlight CV-centric patterns as the norm, promoting efficiency in articulation and perception worldwide.[93]Typological Diversity