Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

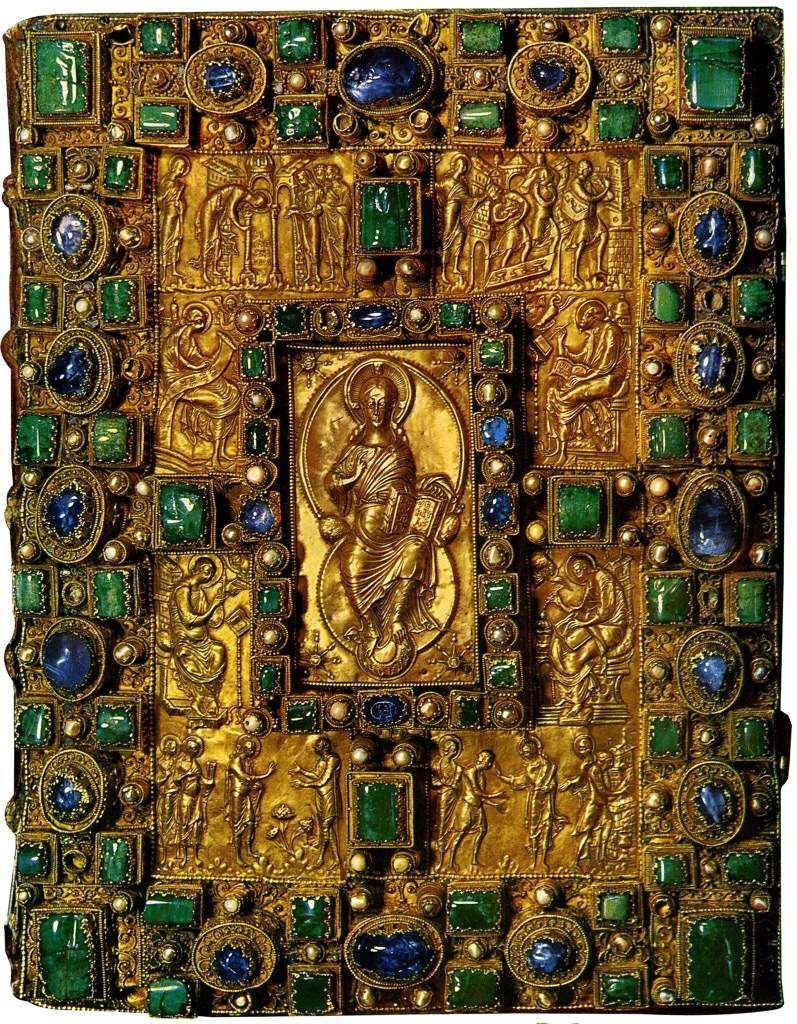

Treasure binding

View on Wikipedia

A treasure binding or jewelled bookbinding is a luxurious book cover using metalwork in gold or silver, jewels, or ivory, perhaps in addition to more usual bookbinding material for book covers such as leather, velvet, or other cloth.[1] The actual bookbinding technique is the same as for other medieval books, with the folios, normally of vellum, stitched together and bound to wooden cover boards. The metal furnishings of the treasure binding are then fixed, normally by tacks, onto these boards. Treasure bindings appear to have existed from at least Late Antiquity, though there are no surviving examples from so early, and Early Medieval examples are very rare. They were less used by the end of the Middle Ages, but a few continued to be produced in the West even up to the present day, and many more in areas where Eastern Orthodoxy predominated. The bindings were mainly used on grand illuminated manuscripts, especially gospel books designed for the altar and use in church services, rather than study in the library.[2]

The vast majority of these bookbindings were later destroyed as their valuable gold and jewels were removed by looters, or the owners when in need of cash. Others survive without their jewels, and many are either no longer attached to a book, or have been moved to a different book.[3] Some survive in major libraries; for example, the Morgan Library in New York City, the John Rylands Library in Manchester, the British Library in London, the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. As the carved ivory reliefs often used could not usually be recycled, these survive in much larger numbers, giving a better idea of the numbers of treasure bindings that once existed. Other examples are recorded in documentary sources but though the books survive the covers do not. The Book of Kells lost its binding after a robbery, and the fate of the missing cover of the Book of Lindisfarne is not recorded.

In the Eastern Orthodox churches treasure bindings have continued to be produced, mainly for liturgical gospel books, up to the present day, and exist in many artistic styles. Other styles of binding using gems, and typically pearls, have a covering of velvet or other textile, to which the gems are sewn or otherwise fixed. These were more likely to be for the private books of a grand person, especially the prayer books and books of hours of female royalty, and may also include embroidery.

Technique and production

[edit]The techniques for producing jewelled bookbinding have evolved over the course of history with the technologies and methods used in creating books. During the 4th century of the Christian era, manuscripts on papyrus or vellum scrolls first became flattened and turned into books with cut pages tied together through holes punched in their margins. Beginning in the 5th century, books were sewn together in this manner using leather thongs to make the bind stronger and longer lasting with wooden boards placed on top and bottom to keep the pages flat. These thongs then came to be laced into the boards and covered entirely by leather.[4]

Boards afforded the opportunity for decorative ornamentation, with metal casings set into the wood for the installation of precious gems, stones, and jewels.[5] The cover material would then be laid over the casings by hand and cut around the rim of the casings to reveal the jewels. The books typically bound were gospels and other religious books made for use within the church. In the Middle Ages, the responsibility of creating adorned books went to metalworkers and guilders, not the bookbinders, who worked with sheets of gold, silver, or copper to create jewelled and enamelled panels that were nailed separately into the wooden boards.[6]

Other forms

[edit]Metalwork book furniture also included metal clasps holding the book shut when not in use, and isolated metal elements decorating a leather or cloth cover, which were very common in grander libraries in the later Middle Ages. Decorative book clasps or straps were made with jewels or repoussé metal from the 12th century onward, particularly in Holland and Germany.[7] In Scotland and Ireland from the 9th century or earlier, books that were regarded as relics of monastic leaders were enshrined in a decorated metal reliquary box called a cumdach, and thereafter were probably not used as books. These were even carried into battle as a kind of standard, worn around the neck by a soldier like a protective amulet. Jewelled slipcases or boxes were also used to house small editions of the Qur’an during this time period.[6]

In fashion in the 16th century were "books of golde": small, devotional books adorned with jewelled or enamelled covers worn as a girdle or around the neck like pieces of jewellery by the English court. These pieces can be seen in portraits from the period and records of jewels from the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI.[8]

History

[edit]

Treasure bindings were a luxury affordable only by wealthy elites, and were commissioned by wealthy private collectors, churches and senior clergy and royalty, and were often commissioned for presentation by or to royal or noble persons.[7] The earliest reference to them is in a letter of Saint Jerome of 384, where he "writes scornfully of the wealthy Christian women whose books are written in gold on purple vellum, and clothed with gems".[9] From at least the 6th century they are seen in mosaics and other images, such as the 6th-century icon of Christ Pantocrator from Saint Catherine's Monastery and the famous mosaic of Justinian I in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna. The ivory panels often placed in the centre of covers were adapted from the style of consular diptychs, and indeed a large proportion of surviving examples of those were reused on book covers in the Middle Ages.[9] Some bindings were created to contain relics of saints, and these large books were sometimes seen suspended from golden rods and carried in the public processions of Byzantine emperors.[10] Especially in the Celtic Christianity of Ireland and Britain, relatively ordinary books that had belonged to monastic saints became treated as relics, and might be rebound with a treasure binding, or placed in a cumdach.

The gems and gold do not merely create an impression of richness, though that was certainly part of their purpose, but served both to offer a foretaste of the bejewelled nature of the Celestial city in religious contexts, and particular types of gem were believed to have actual powerful properties in various "scientific", medical and magical respects, as set out in the popular lapidary books.[11] Several liturgical books given rich bindings can be shown by textual analysis to lack essential parts of the normal textual apparatus of a "working" version of their text, like the Book of Kells and the Codex Aureus of Echternach. They may have been used for readings at services, but in a monastery were essentially part of the furnishings of the church rather than the library; as records from the Abbey of Kells show, the book of Kells lived in the sacristry.

Byzantine and Western medieval treasure bindings are often not entirely unified in style. Apart from being completed at different times, and sometimes in different countries, elements were also removed and readapted for other volumes or reset with new pieces as time passed.[12] For example, the covers now on the Lindau Gospels come from different parts of South Germany, with the lower or back cover created in the 8th century (earlier than the book they now adorn) while the upper or front cover was completed in the 9th century; both incorporate gilded metal ornamented with jewels. It is not known when they were first used on this manuscript.[13]

Outside the monasteries, the emerging bookbinders' guilds of the Middle Ages were often restricted by law with quantitative limitations on the application of jewels. Though this did not significantly affect the craft of decorating books, it did mandate the number of jewels allowed depending on the position or rank of the commissioner of the work.[14] Hardly any early medieval English treasure bindings survived the dissolution of the monasteries and the English Reformation, when ecclesiastical libraries in England were rounded up and treasure bindings removed under an act "to strip off and pay into the king's treasury all gold and silver found on Popish books of devotion." Comparable depredations were not as thorough in the Continental Protestant Reformation, but most bindings survive from Catholic areas that avoided later war and revolutions.[15]

Despite the commoditisation of book production due to the printing press, the artistic tradition of jewelled bookbinding continued in England, though less frequently and often in simpler designs.[16] Luxury bindings were still favoured by the English Court, which is evident from the records on the private library of Queen Elizabeth I, who favoured velvet bindings. On a visit to the Royal Library in 1598, Paul Hentzner remarked on the books "bound in velvet of different colours, though chiefly red, with clasps of gold and silver; some have pearls, and precious stones, set in their bindings."[17] Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, the style evolved to be one using velvet, satin, silk, and canvas in bookbinding decorated less with jewels and more with embroidery, metal threads, pearls, and sequins.[18]

Revival

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

After jewelled bookbinding enjoyed its renaissance, the practice waned until it experienced a revival near the turn of the 20th century in England. Highly influential in the revival of this style were Francis Sangorski and George Sutcliffe of the Sangorski & Sutcliffe bindery. Their bindings were not large uncut gems as in Mediaeval times, but semi-precious stones en cabochon set into beautifully designed bindings with multi-coloured leather inlays and elaborate gilt tooling. The craftsmanship of these bindings was unsurpassable; only their competitors Riviere produced work of similar quality. The most famous of these bindings is "The Great Omar" (1909) on a large copy of FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which included good tooling, inlays of coloured leather, and 1050 jewels in a peacock design scheme.[20] It went down with the Titanic in 1912. Today, a third reproduction of this binding is the only one to survive, after the second one, reproduced to Sutcliffe's design by his nephew Stanley Bray, was damaged in the Blitz during World War II. Bray's second attempt at recreating the design, the third version that survives, was placed in the British Library in 1989.[17]

Other binderies creating books in this style during this period were the companies of Rivière and Zaehnsdorf. The largest collection of these masterpieces was the Phoebe Boyle one; over 100 jewelled bindings were sold in 1923. Jewelled bindings occasionally appear at auction; literature on them is surprisingly scant given their superb quality.

In 1998, Rob Shepherd of Shepherds Bookbinders bought both Zaehnsdorf and Sangorski & Sutcliffe. Presently, binding with jewels is a rare practice, and binding companies both large and small are finding the art form becoming less viable in today's society.[21] Bindings that exist today are housed in private collections or can be found in libraries and museums across the world.

-

Gospel book cover with Byzantine and Western elements of various medieval periods

-

10th-century ivory, with kneeling donor bishop, 12th-century gold and enamel, Mosan

-

The binding of the Mstislav Gospel (Novgorod, 1551) incorporates numerous Byzantine miniatures from the 10th and 11th centuries

-

The cover of the Vienna Coronation Gospels, used in imperial coronations, was replaced in 1500

-

Russian gospel book, 1911, gold and enamel

-

Armenian gospels, 1262, with metal elements over leather

-

The library of the Duke of Burgundy about 1480; books with metal elements probably on velvet

-

Renaissance miniature manuscript formed as a pendant, Italian, c. 1550

-

Unusual secular Rococo binding, using techniques from the making of gold boxes, with mother of pearl and hardstone, Berlin, 1750–1760

-

18th-century German clasped treasure binding

-

Gruel and Engelmann, binding for a book of hours, Paris 1870, silver-gilt and enamel on leather

-

Binding for the so-called Stephanus-codex from Weihenstephan, German, 13th century

-

Front cover to psalter of medieval German origin, with treasure binding incorporating both thirteenth and late-nineteenth/early-twentieth century materials

Notes

[edit]- ^ Greenfield, Jane (2002). ABC of bookbinding: a unique glossary with over 700 illustrations for collectors and librarians. New Castle (Del.) Nottingham (GB): Oak Knoll press The Plough press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-884718-41-0.

- ^ Michelle P. Brown, Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts, revised: A Guide to Technical Terms, 2018, Getty Publications, ISBN 1606065785, 9781606065785 google books

- ^ See for example the Lindau Gospels; as removing and attaching cover plates is relatively easy, moving them between books seems to have been common at all periods. In the last 200 years many art dealers have preferred to treat book and cover as different objects, and have separated them.

- ^ Johnson, Pauline (1990). Creative Bookbinding. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 8. ISBN 9780486263076.

- ^ Johnson, Pauline (1990). Creative Bookbinding. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 11. ISBN 9780486263076.

- ^ a b Marks, P.J.M. (1998). The British Library Guide to Bookbinding: History and Techniques. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 56.

- ^ a b Foot, Miriam M.; Robert C. Akers. "Bookbinding". Oxford Art Online.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Foot, Miriam M. "Bookbinding 1400–1557". Cambridge Histories Online. Cambridge University Press. p. 123.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b Needham, 21

- ^ Diehl, Edith (1980). Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique Vol. 1. New York: Dover Publications. p. 19.

- ^ Metz, 26-30

- ^ Prideaux, Sarah Teverbian; Edward Gordon Duff (1893). An Historical Sketch of Bookbinding. London: Lawrence and Bullen. pp. 179.

An Historical Sketch of Bookbinding.

- ^ Needham, 24–29

- ^ Diehl, Edith (1980). Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique Vol. 1. New York: Dover Publications. p. 52.

- ^ Prideaux, Sarah Teverbian; Edward Gordon Duff (1893). An Historical Sketch of Bookbinding. London: Lawrence and Bullen. pp. 2.

An Historical Sketch of Bookbinding.

- ^ Davenport, Cyril (1898). Cantor Lectures on Decorative Bookbinding. London: William Trounce. p. 8.

- ^ a b Marks, P.J.M. (1998). The British Library Guide to Bookbinding: History and Techniques. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 57.

- ^ Marks, P.J.M. (1998). The British Library Guide to Bookbinding: History and Techniques. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 59.

- ^ "Lindau Gospels Cover". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Middleton, Bernard (1996). A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique (4th ed.). London: The British Library. pp. 125–126.

- ^ Severs, John (27 March 2009). "A Model, Modern Artisan". Printweek: 22–23.

References

[edit]- Metz, Peter (trans. Ilse Schrier and Peter Gorge), The Golden Gospels of Echternach, 1957, Frederick A. Praeger, LOC 57-5327

- Needham, Paul (1979). Twelve Centuries of Bookbindings 400–1600. Pierpont Morgan Library/Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-192-11580-5.

External links

[edit]The links listed below can take you to some currently exhibited examples of jewelled bookbinding in museums and galleries.

- Upper Cover of the Lindau Gospels, c. 880, Switzerland, The Morgan Library & Museum

- Jeweled Book Cover with Byzantine Icon of the Crucifixion, before 1085, Byzantine, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Jeweled Book Cover with Ivory Figures, before 1085, Spanish, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Girdle Prayer Book, London, England, c. 1540-45, British Museum

- Semantic Media Wiki with descriptions and images of treasure bindings in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich