Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

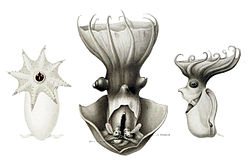

Vampire squid

View on Wikipedia

| Vampire squid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Vampyromorphida |

| Family: | Vampyroteuthidae |

| Genus: | Vampyroteuthis Chun, 1903 |

| Species: | V. infernalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vampyroteuthis infernalis Chun, 1903

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

The vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis, lit. 'vampire squid from hell') is a small cephalopod found throughout temperate and tropical oceans in extreme deep sea conditions.[2][3] The vampire squid uses its bioluminescent organs and its unique oxygen metabolism to thrive in the parts of the ocean with the lowest concentrations of oxygen. It has two long retractile filaments, located between the first two pairs of arms on its dorsal side,[4] which distinguish it from both octopuses and squids, though its closest relatives are octopods. As a phylogenetic relict, it is the only known surviving member of the order Vampyromorphida.[5]

The first specimens were collected on the Valdivia Expedition and were originally described as an octopus in 1903 by German teuthologist Carl Chun, but later assigned to a new order together with several extinct taxa.

Etymology

[edit]The genus name Vampyroteuthis comes from Latin vampyrus, meaning vampire, and Ancient Greek τευθίς (teuthís), meaning "squid". The species name "infernalis" means "of hell" in Latin. The name Vampyroteuthis was reportedly inspired by its dark colour and cloaklike webbing, rather than its habits — it feeds on detritus, not blood.[6][7][8]

Discovery

[edit]The vampire squid was discovered during the Valdivia Expedition (1898–1899), led by Carl Chun. Chun was a zoologist who was inspired by the Challenger Expedition, and wanted to verify that life does indeed exist below 300 fathoms (550 meters).[9] Chun later classified the vampire squid into its family, Vampyroteuthidae.[4] This expedition was funded by the German society Gesellschaft Deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte, a group of German scientists who believed there was life at depths greater than 550 meters, contrary to the Abyssus theory. Valdivia was fitted with equipment for the collection of deep-sea organisms, as well as laboratories and specimen jars, in order to analyze and preserve what was caught. The voyage began in Hamburg, Germany, followed by Edinburgh, and then traced around the west coast of Africa. After navigating around the southern point of Africa, the expedition studied deep areas of the Indian and Antarctic Ocean.[10] Researchers had not before discovered any species from this family that could be traced back to the Cenozoic. This suggests two ideas which are: a notable preservation bias called the Lazarus effect may exist; or an inaccurate determination of when vampire squids originally settled in the deep oceans. The Lazarus effect may result from the scarcity of post-Cretaceous research regions or from the reduced abundance and distribution of vampire squids. In any case, even while the search regions remain the same, it is more difficult to locate and analyze them.[11][8]

Description

[edit]The vampire squid can reach a maximum total length around 30 cm (1 ft). Its 15-centimetre (5.9 in) gelatinous body varies in colour from velvety jet-black to pale reddish, depending on location and lighting conditions.[clarification needed] A webbing of skin connects its eight arms, each lined with rows of fleshy spines or cirri; the inner side of this "cloak" is black. Only the distal halves (farthest from the body) of the arms have suckers.

Its limpid, globular eyes, which appear red or blue, depending on lighting, are proportionately the largest in the animal kingdom, with a 6 inches (15 cm) squid possessing eyes 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter.[12] Their large eyes are accompanied by the similarly expanded optic lobes of their brain.[13]

Mature adults have a pair of small fins projecting from the lateral sides of the mantle. These earlike fins serve as the adult's primary means of propulsion: vampire squid move through the water by flapping their fins. Their beaklike jaws are white. Within the webbing are two pouches wherein the tactile velar filaments are concealed. The filaments are analogous to a true squid's tentacles, extending well past the arms; but differ in origin, and represent the pair that was lost by the ancestral octopus.

The vampire squid is almost entirely covered in light-producing organs called photophores, capable of producing disorienting flashes of light ranging in duration from fractions of a second to several minutes. The intensity and size of the photophores can also be modulated. Appearing as small, white discs, the photophores are larger and more complex at the tips of the arms and at the base of the two fins, but are absent from the undersides of the caped arms. Two larger, white areas on top of the head were initially believed to also be photophores, but are now identified as photoreceptors.[citation needed]

The chromatophores (pigment organs) common to most cephalopods are poorly developed in the vampire squid. The animal is, therefore, incapable of changing its skin colour in the dramatic fashion of shallow-dwelling cephalopods, as such an ability would not be useful at the lightless depths where it lives.

Systematics

[edit]

The Vampyromorphida is the extant sister taxon to all octopuses. Phylogenetic studies of cephalopods using multiple genes and mitochondrial genomes have shown that the Vampyromorphida are the first group of Octopodiformes to evolutionarily diverge from all others.[14][15][16] The Vampyromorphida is characterized by derived characters such as the possession of photophores and of two velar filaments which are likely modified arms. It also shares the inclusion of an internal gladius with other coleoids, including squid, and eight webbed arms with cirrate octopods.

Vampyroteuthis shares its eight cirrate arms with the Cirrata, in which lateral cirri, or filaments, alternate with the suckers. Vampyroteuthis differs in that suckers are present only on the distal half of the arms while cirri run the entire length. In cirrate octopods suckers and cirri run and alternate on the entire length. Also, a close relationship between Vampyroteuthis and the Jurassic-Cretaceous Loligosepiina is indicated by the similarity of their gladii, the internal stiffening structure. Vampyronassa rhodanica from the middle Jurassic La Voulte-sur-Rhône of France is considered as one of a vampyroteuthid that shares some characters with Vampyroteuthis.[17]

The supposed vampyromorphids from the Kimmeridgian-Tithonian (156–146 mya) of Solnhofen, Plesioteuthis prisca, Leptotheuthis gigas, and Trachyteuthis hastiformis, cannot be positively assigned to this group; they are large species (from 35 cm in P. prisca to > 1 m in L. gigas) and show features not found in vampyromorphids, being somewhat similar to the true squids, Teuthida.[18]

Biology

[edit]The vampire squid's worldwide range is confined to the tropics and subtropics.[19][contradictory] This species is an extreme example of a deep sea cephalopod, thought to reside at aphotic (lightless) depths from 600 to 900 metres (2,000 to 3,000 ft) or more. Within this region of the world's oceans is a discrete habitat known as the oxygen minimum zone (OMZ). Within an OMZ, the saturation of oxygen is too low to support aerobic metabolism in most complex organisms. The vampire squid is the only cephalopod able to live its entire life cycle in the minimum zone, at oxygen saturations as low as 3%.

What behavioral data is known has been gleaned from ephemeral encounters with remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROV). Vampire squid are frequently injured during capture, and can survive up to two months in aquaria. It has been hypothesized that they can live for over eight years.[20]

To cope with life in the suffocating depths, vampire squids have developed several adaptations: Of all deep-sea cephalopods, their mass-specific metabolic rate is the lowest. Their blue blood's hemocyanin binds and transports oxygen more efficiently than in other cephalopods,[21] aided by gills possessing an especially large surface area. The animals have weak musculature and a greatly reduced shell,[22] but maintain agility and buoyancy with little effort because of sophisticated statocysts (balancing organs akin to a human's inner ear)[23] and ammonium-rich gelatinous tissues closely matching the density of the surrounding seawater. The vampire squid's ability to thrive in OMZs also keeps it safe from apex predators that require a large amount of oxygen to live.[24]

The vampire squid's large eyes and optic lobes (of their brain) may be an adaptation for greater sensitivity to distant bioluminescence; signs of animals, such as prey aggregations or potential mates. This sensitivity is useful when monitoring a vast area of the water column, which is largely featureless at these depths.[13]

Antipredator behavior

[edit]Like many deep-sea cephalopods, the vampire squid lacks ink sacs. This, along with their low metabolic rate, lead to it adapting various alternate methods of defence. If disturbed, it will curl its arms up outwards and wrap them around its body, turning itself inside-out in a way, making itself seem larger and exposing the spiny projections on its tentacles (the cirri). The underside of the cape is heavily pigmented, concealing most of the body's photophores. The glowing arm tips are clustered together far above the animal's head, diverting attack away from critical areas. This antipredator behavior is dubbed the "pumpkin" or "pineapple" posture.[25][26] The armtips regenerate, so if they are bitten off, they can serve as a diversion allowing the animal to escape while its predator is distracted.[27]

If highly agitated, it may eject a sticky cloud of bioluminescent mucus containing innumerable orbs of blue light from its arm tips.[28] This luminous barrage, which may last nearly 10 minutes, would presumably serve to dazzle would-be predators and allow the vampire squid to disappear into the dark without the need to swim far. The glowing "ink" is also able to stick to the predator, creating what is called the "burglar alarm effect" (making the vampire squid's would-be predator more visible to secondary predators, similar to the Atolla jellyfish's light display). The display is made only if the animal is very agitated, due to the metabolic cost of mucus regeneration.

Their aforementioned bioluminescent "fireworks" are combined with the writhing of glowing arms, along with erratic movements and escape trajectories, making it difficult for a predator to identify the squid itself among multiple sudden targets. The vampire squid's retractile filaments have been suggested to play a larger role in predator avoidance via both detection and escape mechanisms.[4]

Despite these defence mechanisms, vampire squids have been found among the stomach contents of large deep water fish, including giant grenadiers,[29] and deep-diving mammals, such as whales and sea lions.

Feeding

[edit]Vampire squid have eight arms but lack feeding tentacles (like octopods), and instead use two retractile filaments in order to capture food. These filaments have small hairs on them, made up of many sensory cells, that help them detect and secure their prey. They combine waste with mucus secreted from the suckers to form balls of food. As sedentary generalist feeders, they feed on detritus, including the remains of gelatinous zooplankton (such as salps, larvaceans, and medusae jellies) and complete crustaceans, such as copepods, ostracods, amphipods, and isopods,[24] as well as faecal pellets of other aquatic organisms that live above.[8][30] Vampire squids also use a unique luring method where they purposefully agitate bioluminescent protists in the water as a way to attract larger prey for them to consume.[24]

The mature vampire squid is also thought to be an opportunistic hunter of larger prey as fish bones and scales, along with gelatinous zooplankton, has been recorded in mature vampire squid stomachs.[31]

Life cycle

[edit]

If hypotheses may be drawn from knowledge of other deep-sea cephalopods, the vampire squid likely reproduces slowly by way of a small number of large eggs, or a K-selected strategy. Ovulation is irregular and there is minimal energy devotion into the development of the gonad.[32] Growth is slow, as nutrients are not abundant at depths frequented by the animals. The vastness of their habitat and its sparse population make reproductive encounters a fortuitous event. With iteroparity often seen in organisms with high adult survival rates, such as the vampire squid, many low-cost reproductive cycles would be expected for the species.[20]

Reproduction of the vampire squid is unlike any other coleoid cephalopod; the males pass a "packet" of sperm to a female and the female accepts it and stores it in a special pouch inside her mantle. The female may store a male's hydraulically implanted spermatophore for long periods before she is ready to fertilize her eggs. Once she does, she may need to brood over them for up to 400 days before they hatch. Their reproductive strategy appears to be iteroparous, which is an exception amongst the otherwise semelparous Coleoidea.[20] During their life, coleoid cephalopods are thought to go through only one reproductive cycle whereas vampire squid have shown evidence of multiple reproductive cycles. After releasing their eggs, new batches of eggs are formed after the female vampire squid returns to resting. This process may repeat up to, and sometimes more than, twenty times in their lifespan. These spawning events happen quite far apart due to the vampire squid's low metabolic rate.[32]

Few specifics are known regarding the ontogeny of the vampire squid. Hatchlings are about 8 mm in length and are well-developed miniatures of the adults, with some differences: they are transparent, their arms lack webbing, their eyes are smaller proportionally, and their velar filaments are not fully formed.[33] Their development progresses through three morphologic forms: the very young animals have a single pair of fins, an intermediate form has two pairs, and the mature form again has one pair of fins. At their earliest and intermediate phases of development, a pair of fins is located near the eyes; as the animal develops, this pair gradually disappears as the other pair develops.[34] As the animals grow and their surface area to volume ratio drops, the fins are resized and repositioned to maximize gait efficiency. Whereas the young propel themselves primarily by jet propulsion, mature adults prefer the more efficient means of flapping their fins.[35] This unique ontogeny caused confusion in the past, with the varying forms identified as several species in distinct families.[36]

The hatchlings survive on a generous internal yolk supply for an unknown period before they begin to actively feed.[33] The younger animals frequent much deeper waters, feeding on marine snow and zooplankton.[31]

Relationship with humans

[edit]Conservation status

[edit]The vampire squid is currently not on any endangered or threatened species list and they have no known impact on humans.[37] Vampire squids are at increased risk for micro plastic pollution because their diet is mostly marine snow.[38]

Popular culture

[edit]

Following an article in Rolling Stone magazine by Matt Taibbi[39] after the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, the term "vampire squid" has been regularly used in popular culture to refer to Goldman Sachs, the American investment bank.[40][41][42]

Live vampire squids are shown in the "Ocean Deep" episode of Planet Earth.[43]

The Monterey Bay Aquarium (California, United States) became the first facility to put this species on display, in May 2014.[44][45]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Philippe Bouchet (2018). "Vampyroteuthis infernalis Chun, 1903". MolluscaBase. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Herring, P. J.; Dilly, P. N.; Cope, Celia (1994-05-01). "The bioluminescent organs of the deep-sea cephalopod Vampyroteuthis infernalis (Cephalopoda: Vampyromorpha)". Journal of Zoology. 233 (1): 45–55. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb05261.x. ISSN 0952-8369.

- ^ "Vampire Squid, Vampyroteuthis infernalis". MarineBio.org.

- ^ a b c Young, Richard E. (1967). "Homology of Retractile Filaments of Vampire Squid". Science. 156 (3782): 1633–1634. Bibcode:1967Sci...156.1633Y. doi:10.1126/science.156.3782.1633. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1721610. PMID 6025124. S2CID 24349161.

- ^ Yokobori, Shin-ichi; Lindsay, Dhugal J.; Yoshida, Mari; Tsuchiya, Kotaro; Yamagishi, Akihiko; Maruyama, Tadashi; Oshima, Tairo (August 2007). "Mitochondrial genome structure and evolution in the living fossil vampire squid, Vampyroteuthis infernalis, and extant cephalopods". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 44 (2): 898–910. Bibcode:2007MolPE..44..898Y. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.05.009. PMID 17596970.

- ^ "The vampire squid and the vampire fish". National Ocean Service. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Vampyroteuthis infernalis, Deep-sea Vampire squid". The Cephalopod Page. Dr. James B. Wood. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ a b c Krakauer, Hannah (26 September 2012). "Vampire squid from hell eats faeces to survive depths". New Scientist. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "The Valdivia Expedition: Carl Chun's diving into the deep sea". Senses Atlas. 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ "The German Deep-Sea Expedition". The Geographical Journal. 12 (5): 494–496. 1898. Bibcode:1898GeogJ..12..494.. doi:10.2307/1774523. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1774523.

- ^ Košťák, Martin; Schlögl, Ján; Fuchs, Dirk; Holcová, Katarína; Hudáčková, Natalia; Culka, Adam; Fözy, István; Tomašových, Adam; Milovský, Rastislav; Šurka, Juraj; Mazuch1, Martin (February 18, 2021). "Fossil evidence for vampire squid inhabiting oxygen-depleted ocean zones since at least the Oligocene". Communications Biology. 4 (1): 216. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-01714-0. PMC 7893013. PMID 33603225.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Introducing Vampyroteuthis infernalis, the vampire squid from Hell". The Cephalopod Page. Dr. James B. Wood. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ a b Chung, Wen-Sung; Kurniawan, Nyoman D.; Marshall, N. Justin (2021-11-18). "Comparative brain structure and visual processing in octopus from different habitats". Current Biology. 32 (1): 97–110.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.070. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 34798049. S2CID 244398601.

- ^ Uribe, Juan E.; Zardoya, Rafael (May 1, 2017). "Revisiting the phylogeny of Cephalopoda using complete mitochondrial genomes". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 83 (2): 133–144. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyw052. hdl:10261/156228 – via academic.oup.com.

- ^ Lindgren, Annie R.; Pankey, Molly S.; Hochberg, Frederick G.; Oakley, Todd H. (July 28, 2012). "A multi-gene phylogeny of Cephalopoda supports convergent morphological evolution in association with multiple habitat shifts in the marine environment". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 12 (1): 129. Bibcode:2012BMCEE..12..129L. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-129. PMC 3733422. PMID 22839506.

- ^ Strugnell, Jan; Nishiguchi, Michele K. (November 1, 2007). "Molecular phylogeny of coleoid cephalopods (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) inferred from three mitochondrial and six nuclear loci: a comparison of alignment, implied alignment and analysis methods". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 73 (4): 399–410. doi:10.1093/mollus/eym038.

- ^ Rowe, Alison J.; Kruta, Isabelle; Landman, Neil H.; Villier, Loïc; Fernandez, Vincent; Rouget, Isabelle (2022-06-23). "Exceptional soft-tissue preservation of Jurassic Vampyronassa rhodanica provides new insights on the evolution and palaeoecology of vampyroteuthids". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 8292. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.8292R. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12269-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9225997. PMID 35739131.

- ^ Fischer & Riou 2002.

- ^ "Vampyroteithis infernalis". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Hoving, Laptikhovsky & Robison 2015.

- ^ Seibel et al. 1999.

- ^ The evolution of predator avoidance in cephalopods: A case of brain over brawn?

- ^ Stephens & Young 2009.

- ^ a b c Hoving & Robison 2012.

- ^ Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) (26 September 2012). "What the vampire squid really eats". Archived from the original on 2021-12-12 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Vampire Squid Turns "Inside Out"". National Geographic. 4 February 2010. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Robison et al. 2003.

- ^ "Vampire Squid". Aquarium of the Pacific. Retrieved 18 February 2025.

- ^ Drazen, Jeffrey C; Buckley, Troy W; Hoff, Gerald R (2001). "The feeding habits of slope dwelling macrourid fishes in the eastern North Pacific". Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 48 (3): 909–935. Bibcode:2001DSRI...48..909D. doi:10.1016/S0967-0637(00)00058-3.

- ^ "Vampyrotheuthis infernalis (Vampire Squid)" (PDF). The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago. UWI. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ a b Golikov, A. V. (2019). "The first global deep-sea stable isotope assessment reveals the unique trophic ecology of Vampire Squid Vampyroteuthis infernalis (Cephalopoda)". Nature. 9 (1) 19099. Bibcode:2019NatSR...919099G. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55719-1. PMC 6910912. PMID 31836823.

- ^ a b Henk-Jan, Hoving (20 April 2015). "Vampire squid reproductive strategy is unique among coleoid cephalopods". Current Biology. 25 (8): R322–R323. Bibcode:2015CBio...25.R322H. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.018. PMID 25898098.

- ^ a b Young, R. E. (1998). "Morphological Observations On A Hatchling And A Paralarva Of The Vampire Squid, Vampyroteuthis Infernalis Chun (Mollusca : Cephalopoda)". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 112: 661–666. Retrieved 2020-02-09 – via biostor.org.

- ^ Pickford 1949.

- ^ Seibel, Thuesen & Childress 1998.

- ^ Young 2002.

- ^ "Vampire Squid". Marine Life. The MarineBio Conservation Society. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Ferreira, Guilherme; Justino, Anne; Eduardo, Leandro; Lenoble, Véronique; Fauvelle, Vincent; Schmidt, Natascha; Vaske, Teodoro; Frédou, Thierry; Lucena-Frédou, Flávia (January 2022). "Plastic in the inferno: Microplastic contamination in deep-sea cephalopods (Vampyroteuthis infernalis and Abralia veranyi) from the southwestern Atlantic". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 174 113309. Bibcode:2022MarPB.17413309F. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.113309. hdl:11449/230261. PMID 35090293. S2CID 246387973.

- ^ Taibbi, Matt (5 April 2010). "The Great American Bubble Machine". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Zamansky, Jake (8 August 2013). "The Great Vampire Squid Keeps On Sucking". Forbes. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ English, Simon (9 January 2020). "Goldman Sachs: the death of the vampire squid". The Evening Standard. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Blackhurst, Chris (7 February 2020). "Goldman Sachs is still the 'giant vampire squid': When will it decide to change?". The Independent. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "BBC One - Planet Earth, Ocean Deep". BBC. Retrieved 2024-07-13.

- ^ "World's first vampire squid on display at Monterey Bay Aquarium". KION News. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Adams, J. (5 May 2000). "First ever vampire squid goes on display at the Monterey Bay Aquarium". ReefBuilders. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

References

[edit]- Bolstad, Kat (2003). "Deep-Sea Cephalopods: An Introduction and Overview". (Version of 5/6/03, retrieved 2006-DEC-06.)

- Ellis, Richard (1996). "Introducing Vampyroteuthis infernalis, the vampire squid from Hell". The Deep Atlantic: Life, Death, and Exploration in the Abyss. New York: New York : Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-43324-8. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- Fischer, Jean-Claude; Riou, Bernard (2002). "Vampyronassa rhodanica nov. gen. nov sp., vampyromorphe (Cephalopoda, Coleoidea) du Callovien inférieur de la Voulte-sur-Rhône (Ardèche, France)". Annales de Paléontologie. 88 (1): 1–17. Bibcode:2002AnPal..88....1F. doi:10.1016/S0753-3969(02)01037-6. (French with English abstract)

- Hoving, Henk-Jan T.; Robison, Bruce H. (2012). "Vampire squid: Detritivores in the oxygen minimum zone". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1747): 4559–4567. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.1357. PMC 3479720. PMID 23015627.

- Hoving, Henk-Jan T.; Laptikhovsky, Vladimir V.; Robison, Bruce H. (20 April 2015). "Vampire squid reproductive strategy is unique among coleoid cephalopods" (PDF). Current Biology. 25 (8): R322–R323. Bibcode:2015CBio...25.R322H. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.018. PMID 25898098. S2CID 668950. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- Pickford, Grace E. (1949). "Vampyroteuthis infernalis Chun an archaic dibranchiate cephalopod. II". External Anatomy (32). Dana Report: 1–132.

- Robison, Bruce H.; Reisenbichler, Kim R.; Hunt, James C.; Haddock, Steven H. D. (2003). "Light Production by the Arm Tips of the Deep-Sea Cephalopod Vampyroteuthis infernalis" (PDF). Biological Bulletin. 205 (2): 102–109. doi:10.2307/1543231. ISSN 0006-3185. JSTOR 1543231. PMID 14583508. S2CID 16259043. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-16.

- Seibel, Brad A. (2001). "Vampyroteuthis infernalis". Archived from the original on 2005-12-24. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- Seibel, Brad A.; Thuesen, Erik V.; Childress, James J. (1998). "Flight of the vampire: ontogenetic gait-transition in Vampyroteuthis infernalis (Cephalopoda: Vampyromorpha)" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 201 (16): 2413–2424. Bibcode:1998JExpB.201.2413S. doi:10.1242/jeb.201.16.2413. PMID 9679103.

- Seibel, Brad A.; Chausson, Fabienne; Lallier, Francois H.; Zal, Franck; Childress, James J. (1999). "Vampire blood: respiratory physiology of the vampire squid (Cephalopoda: Vampyromorpha) in relation to the oxygen minimum layer". Experimental Biology Online. 4 (1): 1–10. Bibcode:1999EvBO....4a...1S. doi:10.1007/s00898-999-0001-2. S2CID 85327502. (HTML abstract)

- Stephens, P. R.; Young, J. Z. (2009). "The statocyst of Vampyroteuthis infernalis (Mollusca: Cephalopoda)". Journal of Zoology. 180 (4): 565–588. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1976.tb04704.x.

- Young, Richard E. (June 2002). "Taxa Associated with the Family Vampyroteuthidae". Retrieved 2006-12-06.

External links

[edit]- "CephBase: Vampire squid". Archived from the original on 2005-08-17.

- Tree of Life: Vampyroteuthis infernalis.

- National Geographic video of a vampire squid

- Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI): What the vampire squid really eats.

- Vampire squid

- Vampyroteuthis infernalis discussed on RNZ Critter of the Week, 13 Oct 2023

- The vampire squid's photophores and photoreceptors

- Diagram and images of a Vampyroteuthis hatchling

- Photomicrograph of arm tip fluorescence

Vampire squid

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Etymology

Scientific Classification

The vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis Chun, 1903) is the sole extant species in the family Vampyroteuthidae and order Vampyromorphida, a lineage that branches early from other cephalopods and exhibits traits intermediate between octopuses and squid.[7][8] Its taxonomic position reflects phylogenetic analyses placing it within the superorder Octopodiformes, distinct from the squid-inclusive Decapodiformes.[7][2] The full hierarchical classification is as follows:| Rank | Classification |

|---|---|

| Domain | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Mollusca |

| Class | Cephalopoda |

| Subclass | Coleoidea |

| Superorder | Octopodiformes |

| Order | Vampyromorphida |

| Family | Vampyroteuthidae |

| Genus | Vampyroteuthis |

| Species | Vampyroteuthis infernalis |