Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wednesbury

View on Wikipedia

Wednesbury (/ˈwɛnzbəri/[1] locally [ˈwɛnzbriː]) is a market town in the Sandwell district, in the county of the West Midlands, England; it was historically in Staffordshire. It is located near the source of the River Tame and is part of the Black Country. Wednesbury is situated 5 miles (8km) south-east of Wolverhampton, 3 miles (4.4km) south-west of Walsall and 7 miles (11.8km) north-west of Birmingham. At the 2021 Census, the town's built-up area had a population of 20,313.[2]

Key Information

History

[edit]Medieval and earlier

[edit]

The substantial remains of a large ditch excavated in St Mary's Road in 2008, following the contours of the hill and predating the Early Medieval period, has been interpreted as part of a hilltop enclosure and possibly the Iron Age hillfort long suspected on the site.[3] The first authenticated spelling of the name was Wodensbyri, written in an endorsement on the back of the copy of the will of Wulfric Spot, dated 1004. Wednesbury ("Woden's borough")[4] is one of a number of places in England to be named after the pre-Christian deity Woden, the leader of the Old English pantheon.

During the Anglo-Saxon period there are believed to have been two battles fought in Wednesbury, in 592 and 715. According to The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle there was "a great slaughter" in 592 and "Ceawlin was driven out". Ceawlin was a king of Wessex and the second Bretwalda, or overlord of all Britain. The 715 battle was between Mercia (of which Wednesbury was part) and the kingdom of Wessex. Both sides allegedly claimed to have won the battle, although it is believed that the victory inclined to Wessex.[5]

Wednesbury was fortified by Æthelflæd (Ethelfleda), daughter of Alfred the Great and known as the Lady of Mercia. She erected five fortifications to defend against the Danes at Bridgnorth, Tamworth, Stafford and Warwick, with Wednesbury in the centre. Wednesbury's fort would probably have been an extension of an older fortification and made of a stone foundation with a wooden stockade above. Earthwork ramparts and water filled ditches would probably have added to its strength.[5] A plaque on the gardens between Ethelfleda Terrace and St Bartholomew's church states that the gardens there – created in the 1950s – used stone from the graff, or fighting platform, of the old fort. Exploration of the gardens reveals several dressed stones, which appear to be those referred to on the plaque.[6]

In 1086, the Domesday Book describes Wednesbury (Wadnesberie) as being a thriving rural community encompassing Bloxwich and Shelfield (now part of Walsall). During the Middle Ages the town was a rural village, with each family farming a strip of land with nearby heath being used for grazing. The town was held by the king until the reign of Henry II, when it passed to the Heronville family.

Medieval Wednesbury was very small, and its inhabitants would appear to have been farmers and farm workers. In 1315, coal pits were first recorded, which led to an increase in the number of jobs. Nail making was also in progress during these times. William Paget was born in Wednesbury in 1505, the son of a nail maker. He became Secretary of State, a Knight of the Garter and an Ambassador. He was one of executors of the will of Henry VIII.

It was historically when in Staffordshire a part of the Hundred of Offlow.

Post-Medieval

[edit]

In the 17th century Wednesbury pottery – "Wedgbury ware" – was being sold as far away as Worcester, while white clay from Monway Field was used to make tobacco pipes.

By the 18th century the main occupations were coal mining[7] and nail making. With the introduction of the first turnpike road in 1727 and the development of canals and later the railways came a big increase in population.[7] In 1769 the first Birmingham Canal was cut to link Wednesbury's coalfields to the Birmingham industries. The canal banks were soon full of factories.

In 1743, the Wesleys and their new Methodist movement were severely tested.[8] Early in the year, John and Charles Wesley preached in the open air on the Tump.[9] They were warmly received and made welcome by the vicar. Soon afterwards another preacher came and was rude about the current state of the Anglican clergy. This angered the vicar, and the magistrates published a notice ordering that any further preachers were to be brought to them. When Wesley next came his supporters were still there but a crowd of others heckled him and threw stones. Later the crowd came to his lodgings and took him to the magistrates, but they declined to have anything to do with Wesley or the crowd. The crowd ill-treated Wesley and nearly killed him but he remained calm. Eventually they came to their senses and returned him to his hosts.

Soon afterward, the vicar asked his congregation to pledge not to associate with Methodists, and some who refused to pledge had their windows smashed. Others who hosted Methodist meetings had the contents of their houses destroyed. This terrible episode came to an end in December when the vicar died. After that mainstream Anglican and Methodist relations were generally cordial. Methodism grew strongly and Wesley visited often, almost until his death.[10][11] Francis Asbury, Richard Whatcoat and the Earl of Dartmouth are among those who attended Methodist meetings, all to have a profound effect on the United States.[12]

Wednesbury was incorporated as a municipal borough, with its headquarters at Wednesbury Town Hall, in 1886,[13][14] the district contained only the civil parish of Wednesbury, on 1 April 1966 the district was abolished and merged with the County Borough of West Bromwich and the County Borough of Walsall.[15][16] The parish was also abolished on 1 April 1966 and merged with West Bromwich and Walsall.[17] In 1961 the parish had a population of 34,511.[18]

In 1887, Brunswick Park was opened to celebrate Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee.

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]

On the evening of 31 January 1916, Wednesbury was hit by one of the first wave of German Zeppelins aimed at Britain during the First World War. Joseph Smith and his three children were killed in their house in the King Street area. His wife survived, having left the house to investigate the cause of a loud noise at a nearby factory, caused by the first bombs falling.[19]

The first council houses in Wednesbury were built in the early 1920s, but progress was slow compared to nearby towns including Tipton and West Bromwich. By 1930, a mere 206 families had been rehoused from slums. However, the building of council houses quickened at the start of the 1930s; the 1,000th council house was occupied before the end of 1931. By 1935, some 1,250 older houses had been demolished or earmarked for demolition. By 1944 there were more than 3,000 council properties; by 1959, more than 5,000. The largest development in Wednesbury was the Hateley Heath estate in the late 1940s and early 1950s, which straddled the border of Wednesbury and West Bromwich.[20]

In 1947, the Corporation granted a licence for the operation of a cinema, on the condition that no children under 15 were to be admitted on Sundays. The cinema operator challenged this decision in court, claiming that the imposition of the condition was outside the corporation's powers. The court used this case to establish a general test for overturning the decision of a public body in this type of case, which is now known as "Wednesbury unreasonableness".[21]

The borough of Wednesbury ceased to exist in 1966. Much of its area was absorbed into West Bromwich and small parts went into the County Borough of Walsall. The Wednesbury section of Hateley Heath was absorbed into West Bromwich, and Wednesbury gained the Friar Park estate from West Bromwich.[22] The Dangerfield Lane estate (developed during the interwar and early postwar years) was absorbed into Darlaston, which was now part of an expanded Walsall borough. In 1974 West Bromwich amalgamated with Warley (i.e. Oldbury, Rowley Regis and Smethwick) to form the present-day borough of Sandwell.[23] Wednesbury has the postcode WS10, shared with Darlaston in the borough of Walsall.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Wednesbury's traditional industry declined and unemployment rose, but since 1990 new developments such as a new light industrial estate, a retail park and the pedestrian-only Union Street have given a new look to the town. The traditional market is still a feature of the bustling centre, and the streets around Market Place are now a protected conservation area.

In the late 1980s, land near junction 9 of the M6 motorway was designated as the location for a retail development. Swedish furniture retailer Ikea was the first to move in; its superstore opened in January 1991. In the 1990s the retail park grew to include several more large units, but most of these were empty by 2009 due to the recession. However, most of the units were occupied again by 2012 and the retail is home to numerous retailers. The retail park was expanded in 2017 with the construction of more retail units and 'eateries', and the car park was remodelled to create more parking spaces.[24]

Wednesbury was the scene of two major tragedies during the second half of the 20th century. On 21 December 1977, four siblings aged between 4 and 12 years died in a house fire in School Road, Friar Park, at the height of the national firefighters strike. The house was demolished soon afterwards, leaving a gap in a terrace of council houses.[25] On 24 September 1984, four pupils and a teacher from Stuart Bathurst RC High School were killed when their minibus was struck by a roll of steel which fell from the back of a lorry, on Wood Green Road close to the park keepers house.[26]

For well over 100 years, Wednesbury was dominated by the huge Patent Shaft steel works, which opened during the 19th century and closed in 1980. The factory was demolished in 1983, and within a decade had been developed for light industry and services. The iron gates of the factory still exist and are mounted on the traffic island at Holyhead Road and Dudley Street.

In 2003, Wednesbury Museum and Art Gallery staged Stuck in Wednesbury,[27] the first show in a public gallery of the Stuckism international art movement.[28]

The archives for Wednesbury Borough are held at Sandwell Community History and Archives Service in Smethwick.

Transport history

[edit]Wednesbury was first connected to the rail network in the mid-19th century, and has been served by heavy and light rail for all but six years since then.

The South Staffordshire Line between Walsall and Stourbridge served Wednesbury until 1993. Passenger services were withdrawn after Wednesbury railway station closed in 1964 under the Beeching Axe,[29] but a steel terminal soon opened on the site and did not close until December 1992, with the railway closing on 19 March 1993 after serving the town for some 150 years.

Until 1972, the town was served by the former Great Western Railway line between Birmingham and Wolverhampton at Wednesbury Central station. Passenger trains were withdrawn at this time, with Wednesbury-Birmingham section of the line through West Bromwich closing. The Bilston-Wolverhampton section survived for another decade before closing over the winter of 1982/83. The final section between Wednesbury and Bilston, serving a scrapyard at Bilston, remained open until 30 August 1992, before the line was closed to allow for the creation of the Midland Metro, which opened in May 1999.

A steam tram service opened to Dudley, also serving Tipton, on 21 January 1884. The line was electrified in 1907 but discontinued in March 1930 on its replacement by Midland Red buses.[30]

The town's current bus station was opened in the autumn of 2004 on the site of its predecessor.

Oakeswell Hall

[edit]Second in importance to Wednesbury manor house was Oakeswell Hall, built c. 1421 by William Byng. The property descended to the family of Jennyns. By 1662 the house was known as Okeswell or Hopkins New Hall Place (it being adjacent to the Hopkins family's New Hall Fields). Richard Parkes, a Quaker ironmaster, bought it in 1707 and moved in the following year. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries it was a farmhouse. Between 1825 and 1962 it had several different owners, including Joseph Smith (the first town clerk) who greatly restored it. In 1962 it was demolished.[31]

Dr Walter Chancellor Garman (1860–1923), a general practitioner, and his wife, Margaret Frances Magill[32][33] lived at Oakeswell Hall.[34] Their children included the Garman sisters who were associated with the Bloomsbury group. There were nine children, seven sisters and two brothers: Mary (1898), Sylvia (1899), Kathleen (1901), Douglas (1903), Rosalind (1904), Helen (1906), Mavin (1907), Ruth (1909) and Lorna (1911).

Demography

[edit]At the 2021 census, Wednesbury's built-up area population was recorded as having a population of 20,313. Of the findings, the ethnicity and religious composition of the wards separately were:

| Wednesbury: Ethnicity (2021 Census)[35] | |||||||||||||

| Ethnic group | Population | % | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 15,594 | 76.7% | |||||||||||

| Asian or Asian British | 3,109 | 15.3% | |||||||||||

| Black or Black British | 713 | 3.5% | |||||||||||

| Mixed | 591 | 2.9% | |||||||||||

| Other Ethnic Group | 229 | 1.1% | |||||||||||

| Arab | 82 | 0.3% | |||||||||||

| Total | 20,313 | 100% | |||||||||||

The religious composition of the built-up area at the 2021 Census was recorded as:

| Wednesbury: Religion (2021 Census) | |||||||||||||

| Religious | Population | % | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian | 9,657 | 50.1% | |||||||||||

| Irreligious | 6,389 | 33.1% | |||||||||||

| Muslim | 2,008 | 10.4% | |||||||||||

| Sikh | 673 | 3.5% | |||||||||||

| Hindu | 424 | 2.2% | |||||||||||

| Other religion | 80 | 0.4% | |||||||||||

| Buddhist | 52 | 0.3% | |||||||||||

| Jewish | 1 | 0.1% | |||||||||||

| Total | 20,313 | 100% | |||||||||||

Transport

[edit]Roads

[edit]Wednesbury is on Thomas Telford's London to Holyhead road, built in the early 19th century. The section between Wednesbury and Moxley was widened in 1997 to form a dual carriageway, completing the Black Country Spine Road that had been in development since 1995 when the route between Wednesbury and West Bromwich had opened, along with a one-mile route to the north of Moxley linking with the Black Country Route. The original plan was for a completely new route between Wednesbury and Moxley, but this was abandoned as part of cost-cutting measures, as were the planned grade-separated junctions, which were abandoned in favour of conventional roundabouts.

Buses

[edit]The bus station, rebuilt in 2004, is in the town centre near the swimming baths. It facilitates links to Wolverhampton, West Bromwich, Walsall and Dudley, where connections can be made to the Merry Hill Shopping Centre and Birmingham

Railways

[edit]Since 1999, Wednesbury has been served by the West Midlands Metro light rail tram system, with stops at Great Western Street and Wednesbury Parkway. It runs from Wolverhampton to Birmingham; the maintenance depot is also here.

Wednesbury's rail links are set to improve further with the completion of a new Metro tram line running to Brierley Hill, via Tipton and Dudley, making use of the disused South Staffordshire Line. Originally planned to open in 2023, the project was put back due to lack of funds and is now being built in two parts with part one (to Dudley) now expected to open in 2025. The completion of the extension depends upon funds being available.[36]

Districts

[edit]- Church Hill: near the town centre, is notable for being the location of St Bartholomew's Church.

- Brunswick: to the immediate north of the town centre, was mostly built at the start of the 20th century around Brunswick Park.

- Friar Park: originally in West Bromwich, it was built in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

- Myvod Estate: approximately one mile to the north of the town centre towards the border with Walsall, was built in the 1920s as Wednesbury's first major council housing development.

- Wood Green: situated around the A461 road northwards in the direction of Walsall. Landmarks include Stuart Bathurst RC High School, and on the opposite site of the road is Wood Green Academy. The parish church is St Paul's. Since 1990, a large retail development has sprung upon around Wood Green, extending to the site of the former FH Lloyd steel plant in Park Lane.

- Golf Links: mostly built in the 1940s and 1950s with both private and council housing, in the south of the town.

- Woods Estate: to the north-east of the town centre, was built mostly as council housing between 1930 and 1962.

- King's Hill: to the north of the town centre.

Wards

[edit]- Wednesbury North : Wednesbury Central, Wood Green & Old Park

- Wednesbury South : Hill Top, Ocker Hill (part), Golf Links, Millfields, Harvills Hawthorn

- Friar Park : Woods & Mesty Croft, Friar Park

Media

[edit]Local news and television programmes are provided by BBC West Midlands and ITV Central. Television signals are received from the Sutton Coldfield TV transmitter.[37]

Local radio stations are BBC Radio WM, Heart West Midlands, Smooth West Midlands, Hits Radio Black Country & Shropshire, Greatest Hits Radio Birmingham & The West Midlands, Greatest Hits Radio Black Country & Shropshire and Black Country Radio, a community based station. [38]

The town is served by the local newspapers, Wednesbury Herald and Express & Star.[39]

Schools

[edit]- Tameside Primary Academy

- Park Hill Primary School

- St Mary’s Roman Catholic Primary School

- Old Park Primary School

- St John's Primary Academy

- Stuart Bathurst Catholic High School

- Wodensborough Ormiston Academy

- Wood Green Academy

- Mesty Croft Academy

Notable people

[edit]

- William Paget KG PC (1506–1563), statesman and accountant.[40]

- Moses Haughton the elder (ca.1734 – 1804), engraver, designer and painter.[41]

- Richard Whatcoat (1736–1806), the third bishop of the American Methodist Episcopal Church.

- Moses Haughton the younger (1773–1849), engraver and painter, often of miniatures.[42]

- John Brotherton (1829–1917), tube manufacturer and Mayor of Wolverhampton 1883/84.

- John Ashley Kilvert (1833–1920), soldier in the Charge of the Light Brigade, later Mayor of Wednesbury

- Wilson Lloyd (1835–1908), iron founder and twice MP for Wednesbury

- The Garman Sisters (ca.1900-ca.1975), members of the Bloomsbury Group, lived at Oakeswell Hall

- Gwynneth Holt (1909–1995), artist known for her ivory sculptures on religious subjects.

- Kathleen Margaret Midwinter (1909–1995), the first female Clerk of the House of Commons.

- Henry Treece (1911–1966), poet and writer, mostly of children's historical novels.

- Richard Wattis (1912–1975), character actor

- Kevin Laffan (1922–2003), screenwriter, author and actor; created the soap opera now titled Emmerdale.

- Peter Archer, Baron Archer of Sandwell QC, PC (1926–2012), lawyer and MP for Rowley Regis and Tipton from 1966 until 1992

- Jon Brookes (ca.1945–2013), drummer for The Charlatans

- Alex Lester (born 11 May 1956), BBC Radio 2 overnight broadcaster

- David Howarth (born 1958), politician and MP for Cambridge, 2005 to 2010.

- Karl Shuker (born 1959), zoologist, cryptozoologist and author.

- Lee Payne (born 1960), the founding bassist and songwriter of heavy metal, power metal band Cloven Hoof.

- Baga Chipz (born 1989), drag queen and TV personality

Sport

[edit]- Billy Malpass (1867–1939), footballer who played 133 games for Wolves

- Marty Hogan (1869–1923), baseball player and manager.[43]

- Fred Shinton (1883–1923), footballer played 163 games, most for The Albion and Leicester City

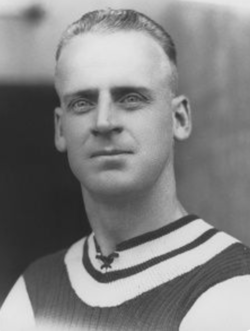

- Billy Walker (1897–1964), footballer who played for 478 games for Aston Villa and 18 for England and was later manager of Nottingham Forest's FA Cup winning side in 1959

- Syd Gibbons (1907–1953), footballer, played 299 games for Fulham

- Jack Burkitt (1926–2003), footballer who played 463 games for Nottingham Forest

- Roy Proverbs (1932–2017), footballer, played over 350 games, mainly for Gillingham

- Wilf Carter (1933–2013), footballer who played over 350 games, mainly for Plymouth Argyle

- Norman Deeley (1933–2007), footballer, played 279 games including 206 for Wolves

- Gordon Wills (1934–2018), footballer who played 300 games mainly for Notts County and Leicester City

- Johnny Gill (born 1941), footballer who played 343 games, mainly for Hartlepool United

- Alan Hinton (born 1942), footballer, played over 500 games, including 253 for Derby County

- Roy Cross (born 1947), footballer, played 298 games, including 136 for Port Vale

- Brian Caswell (born 1956), footballer who played 425 games including 400 for Walsall

- John Thomas (born 1958), footballer who played 365 games

- Aaron Williams (born 1993), footballer who played over 360 games

Notable employers

[edit]Current

[edit]- Property developers J.J. Gallagher had purchased the bulk of the Lloyd site in 1988 and once mineshafts were filled in, decontamination was completed the land was suitable for mass retail development. IKEA purchased the former F.H. Lloyd steel plant from Triplex in 1988, and opened one of its first British stores on the site in January 1991, just 14 months after the development had been given the go-ahead.[44]

- Morrisons opened a supermarket in the town centre on 4 November 2007, creating some 350 new jobs. A number of council bungalows and a section of the town centre shops had been demolished to make way for it.

- Quantum print and packaging Limited employs 30 people since relocating to Wednesbury in 2013 from their Willenhall base. The factory occupies a 30000 sq ft site in the town centre.

- In 2016, successful German supermarket chain Lidl opened a new distribution centre just off Wood Green Road, on land near Junction 9 Retail Park.

- MSC Industrial Supply a leading distributor of metalworking and maintenance, repair, and operations (MRO) products and services

Former

[edit]- Patent Shaft (part of the Cammel Laird group) steelworks was erected on land off Leabrook Road near the border with Tipton in 1840, serving the town for 140 years before its closure on 17 April 1980 – an early casualty of the recession. Demolition of the site took place in 1983.

- Metro Cammell (Metropolitan Company) set up business after acquiring all of the assets of the Patent Shaft in 1902, in 1919 Vickers ltd acquired the shares of The Metropolitan Company ltd, in 1929 Vickers ltd and Cammel laird and Co merged their interests to form The Metropolitan Cammel Carriage and Wagon works Co ltd, where it produced railway coach bodies, turntables, Bridges, railway wagons and pressings at the Old Park works. The plant remained opened until 1964. The work and its workers were transferred to the Washwood heath works Birmingham. The site was sold to The Rubbery Owen group.[45]

- F.H. Lloyd steelworks was formed at a site on Park Lane near the boundaries with Walsall and Darlaston during the 1880s, and provided employment for some 100 years. However, F.H. Lloyd was hit hard by the economic problems of the 1970s and early 1980s, and went out of business in 1982. Triplex Iron Foundry of Tipton then took the site over, but the new owners kept the factory open for just six years and it was then sold to Swedish home products company IKEA in 1988, being demolished almost immediately to make way for the superstore, which opened in January 1991.[46]

- A Cargo Club supermarket-style retail warehouse, part of the Nurdin and Peacock group, opened in July 1994. It was one of three Cargo Club stores in Britain, and the venture was not a success: by the end of 1995 it had been shut down following heavy losses.[47]

Cock-fighting ballad

[edit]A ballad about cock-fighting in the town called "Wedgebury Cocking" or "Wednesbury Cocking" became well known in the 19th century.[48] It begins:

At Wednesbury there was a cocking,

A match between Newton and Skrogging;

The colliers and nailers left work,

And all to Spittles' went jogging

To see this noble sport.

Many noted men there resorted,

And though they'd but little money,

Yet that they freely sported.

References

[edit]- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ "West Midlands (United Kingdom): Settlements in Counties and Unitary Districts - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "West Midlands – Birmingham Area" (PDF). Archaeological Investigations Project. Bournemouth University. 2008. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Mills, A. D.; Room, Adrian (2002). The Oxford Names Companion. Oxford: the Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198605617.

- ^ a b F[rederick] W[illiam] Hackwood (1903). Wednesbury Ancient and Modern. Brewin Books Ltd. ISBN 1-85858-219-9 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Tim Clarkson (26 March 2019). "Æthelflæd and Wednesbury". SASVA: notes on the Viking Age. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

These gardens occupy the site of the graff or fighting platform of the stronghold built by Ethelfleda, princess of Mercia, daughter of King Alfred the Great, about A.D.916 when she fortified Wednesbury against the Danes.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ a b John Holland (1835). The History and Description of Fossil Fuel, the Collieries, and Coal Trade of Great Britain. Whittaker; G. ISBN 1-144-62255-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Charles H. Goodwin, "Vile or reviled? The causes of the anti-Methodist riots at Wednesbury between May, 1743 and April, 1744 in the light of New England revivalism." Methodist history 35#1 (1996): 14–28.

- ^ A step for travellers to get on or off their horses

- ^ Hackwood, Frederick William (1900). "Religious Wednesbury, its Creeds, Churches and Chapels". Dudley: Dudley Herald.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wesley, John (1745). "Modern Christianity Exemplified at Wednesbury" (Second ed.).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help). Witness statements collected by John Wesley, quoted by Hackwood - ^ John Lednum (1859). A History of the Rise of Methodism in America. Lednum. ISBN 1-112-17734-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Brunswick Park: Historical Summary". Archived from the original on 21 September 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- ^ "Barratt Homes: Brief history of Wednesbury". Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- ^ "Archive catalogues | Our collections | Sandwell Council". Sandwell.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Relationships and changes Wednesbury MB through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ "Wednesbury Registration District". UKBMD. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ "Population statistics Wednesbury Ch/CP/AP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ "HELLFIRE CORNER - Wednesbury - Zeppelin". Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "A History of Wednesbury". Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Wednesbury unreasonableness". Practical Law. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "West Bromwich: Social life | British History Online". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ The Sandwell Official Guide, British-publishing.com

- ^ Sandwell MBC: Conservation Archived 12 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A truce is not enough for mother who lost all in 1977". Telegraph.co.uk. 27 October 2002. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Getty Images". Gettyimages.com. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Archive: Diary", stuckism.com. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Milner, Frank ed., The Stuckists Punk Victorian, p.210, National Museums Liverpool 2004, ISBN 1-902700-27-9. An essay from the book is online at stuckism.com.

- ^ "Wednesbury Town Station". Railaroundbirmingham.co.uk. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Brief History of Tipton". Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ Bev Parker A History of Wednesbury; accessed 5 June 2019

- ^ Harrington, Illtyd (9 September 2004). "Three sisters with a love, and lust, for life". Camden New Journal. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Walter Chancellor Garman MD + Margaret Frances Magill". Stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ "Kathleen Garman". Spartacus-Educational.com. 19 August 1959. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Wednesbury (West Midlands, West Midlands, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de.

- ^ "Midland Metro Website – Wednesbury to Brierley Hill Extension". Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ "Sutton Coldfield (Birmingham, England) Full Freeview transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "Black Country Radio". Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ "Newspapers". Sandwell Council. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 452.

- ^ Cust, Lionel (1891). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 25. pp. 169–170.

- ^ Cust, Lionel (1891). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 25. p. 170.

- ^ Reichler, Joseph L., ed. (1979) [1969]. The Baseball Encyclopedia (4th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing. ISBN 0-02-578970-8.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "A History of Wednesbury". Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ "ABC Couplers". Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ "Cargo Club: the profitable failure". Grocer. 1995.

- ^ Egan, Pierce (1836). Pierce Eganʼs Book of Sports, and Mirror of Life Embracing the Turf, the Chase, the Ring and the Stage Interspersed with Original Memoirs of Sporting Men. London: Thomas Tegg and Son. pp. 154–155.

External links

[edit]- The Black Country 1969, Video, ATV, 1969

Wednesbury

View on GrokipediaWednesbury is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Sandwell within the West Midlands county of England, historically situated in Staffordshire.[1][2] At the 2021 census, the town had a population of 41,335 residents.[1] Its name originates from the Anglo-Saxon "Wodnesburh," referring to a fortified settlement associated with the god Woden.[3] Wednesbury forms part of the Black Country, a region defined by its dense concentration of coal mines, ironworks, and factories during the Industrial Revolution, which transformed the local landscape and economy through heavy manufacturing.[2] The town's industrial heritage prominently features large-scale tube production, steel fabrication, and the manufacture of railway axles, contributing significantly to Britain's infrastructural development in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[2] Key landmarks include the medieval St Bartholomew's Church, a Scheduled Ancient Monument, and the Wednesbury Old Canal, which facilitated industrial transport.[4] Modern Wednesbury maintains a commercial center with retail and service sectors, while preserving elements of its manufacturing past amid urban regeneration efforts.[5]

Geography

Location and administrative status

Wednesbury is situated at coordinates approximately 52°33′N 2°1′W within the Sandwell Metropolitan Borough in the West Midlands county of England.[6] It forms part of the Black Country conurbation, positioned roughly 7 miles (11 km) northwest of Birmingham city centre.[7] Historically within Staffordshire, Wednesbury was integrated into the Sandwell Metropolitan Borough upon its creation on 1 April 1974 during the local government reorganization that established the metropolitan counties.[8][9] The borough encompasses Wednesbury along with adjacent towns such as West Bromwich and Tipton, under the administration of Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council.[10]Topography and environment

Wednesbury occupies a low-lying position within the gently undulating topography of the Birmingham region's drift-covered areas, where superficial deposits overlie bedrock and constrain natural drainage patterns.[11] The underlying geology forms part of the South Staffordshire Coalfield, dominated by Carboniferous coal measures comprising interbedded sandstones, mudstones, and coal seams, which have historically influenced surface stability and resource extraction.[12] These strata, part of the Paleozoic outcrop in the South Staffordshire Horst, contribute to the area's flat to moderate relief, with elevations typically ranging from 120 to 160 meters above sea level, limiting steep gradients and promoting broad, even terrain.[12] Environmental challenges stem primarily from legacy mining activities, including subsidence risks from collapsed underground workings in both coal and limestone mines. A notable incident occurred in 1978 on Wednesbury's outskirts, where pillar collapse in the Cow Pasture limestone mine triggered severe surface deformation and property damage, exemplifying ongoing geohazards in the coalfield.[13] Such events arise from voids and pillar failures at depths up to 150 meters, posing constraints on development through potential instability and requiring site-specific assessments for new infrastructure.[14] Proximity to the River Tame introduces fluvial flood risks, particularly in low-lying zones near Hydes Road, The Woods, and Bescot, where the Environment Agency maintains a dedicated flood warning area for watercourse overflow during heavy rainfall.[15] Local green spaces, such as those in Friar Park, provide limited natural buffers amid urban pressures, though enhancement projects aim to improve accessibility and ecological quality without altering underlying topographic constraints. The region exhibits a temperate maritime climate characteristic of the West Midlands, with average annual precipitation around 770 mm, distributed fairly evenly but peaking in autumn, as recorded in nearby Birmingham data.[16]History

Etymology and early settlement

The name Wednesbury originates from Old English Wōdnesbyriġ, translating to "Woden's burh" or the fortified settlement dedicated to Woden, the Anglo-Saxon god of war and wisdom, equivalent to the Norse Odin, indicating pagan roots prior to Christianization. The element burh denotes a defended enclosure or stronghold, common in Anglo-Saxon place names for strategic sites. This etymology underscores the site's early association with pre-Christian religious and military significance in the Mercian landscape.[17][3] The earliest documented reference appears in the Domesday Book of 1086, spelled Wadnesberie, describing Wednesbury as a manor in Staffordshire's Offlow Hundred held by the king, with an estimated 9 households (implying a population of around 140 persons based on contemporary multipliers) engaged in agriculture and rendering customary dues like 12 swine and honey. Pre-Conquest evidence points to its role as a royal Saxon burh, likely fortified for defense against Viking raids in the late 9th and early 10th centuries during Mercian resistance under leaders like Æthelflæd, who coordinated burh networks across the region from circa 910 onward. Archaeological traces of such defenses may align with a possible Iron Age hillfort precursor on Church Hill, though confirmation remains tentative absent extensive excavation.[18][19][20] Roman-era finds, such as scattered artifacts, suggest peripheral activity near nearby routes like Watling Street but no organized settlement, with substantive habitation emerging only in the Anglo-Saxon era amid Mercian consolidation. This defensive burh function, prioritizing elevated terrain for visibility and fortification, reflects pragmatic responses to invasion pressures rather than expansive urbanization, as evidenced by the modest Domesday holdings of arable land, meadow, and woodland.[20][3]Medieval and post-medieval development

In 1086, Wednesbury appeared in the Domesday Book as a manor in the hundred of Offlow, Staffordshire, held directly by King William I, with an estimated 9.3 households including 16 villagers and 11 smallholders engaged primarily in agriculture.[18] The estate comprised 9 ploughlands (1 held by the lord and 7 by men), 1 acre of meadow, extensive woodland measuring 2 leagues by 1 furlong plus 3 furlongs, and 1 mill valued at 2 shillings, indicating a rural economy centered on arable cultivation, pastoral farming, and limited milling, though the land was noted as partially waste.[18] Following the Conquest, ownership shifted; by 1164, King Henry II had granted the manor to Ralph Boterel as a tenant under the barony of d'Oyly, with an annual taxable value of £4.[21] The de Heronville family subsequently held lordship from around 1182, with John de Heronville documented as lord from 1255 to 1315, during which the manor house included a hall, solar, brewhouse, bakery, stables, and associated demesne lands of 120 acres arable and 10 acres meadow.[21] Common fields such as Monway Field and Church Field supported communal agriculture, while a manorial mill was rented to Bordesley Abbey's monks for 10 shillings annually and sublet locally.[21] Subsidy rolls from 1332–1333 record 13 taxpayers contributing £1 19s. 1d., reflecting modest prosperity under the reduced 1/10th tax rate for ancient manors.[21] St Bartholomew's Church, Wednesbury's principal medieval architectural feature, was first mentioned in records dating to 1088, with a 13th-century structure noted in plea rolls from 1210–1211.[22] The church retained medieval elements, including a 13th-century window, amid later rebuildings, serving as a focal point for local religious and communal life under the Diocese of Lichfield.[23] ![St Bartholomew's Church, a key medieval site in Wednesbury][float-right]Post-medieval developments saw continued manorial evolution, with the estate passing to the Beaumont family by the mid-15th century—Henry Beaumont's 1471 will bequeathing funds for a church chaplain—and later to the Comberfords through marriage in the 16th century.[21][24] Agriculture remained the economic foundation, supplemented by early extraction of coal and ironstone resources documented from 1315, though formal market rights were absent until the 18th century; informal trade likely occurred via the manorial Court Leet, which regulated local justice and exchange from Saxon origins.[21] Secondary residences like Oakeswell Hall, constructed around 1421 by William Byng, underscored gentry investment in the locale.[21]

Industrial era and 19th century growth

Wednesbury's industrialization accelerated in the late 18th century, driven primarily by coal mining and the expansion of wrought iron production. Coal extraction, documented since the medieval period but intensifying with deeper shafts in the 18th century, fueled local forges and supported export via emerging transport networks. The Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN), including the Wednesbury Old Canal opened in 1769, facilitated coal transport from Wednesbury's coalfields to Birmingham, spurring economic activity and attracting laborers.[25][26] Nail-making, a longstanding cottage industry since around 1500, reached its peak in the 19th century as hand-forging techniques proliferated, with thousands of small forges operating in the Black Country region by the 1830s. Wrought iron tube drawing emerged as a specialty, pioneered by figures like John Russell who began production in 1811 using tapered wrought iron tubes for applications such as gun barrels and later railways. By the 1850s, Wednesbury firms held a near-monopoly in the iron tube trade, supplying railways and becoming the area's largest iron exporter, bolstered by steam-powered rolling mills and forges like Wednesbury Forge, active since the 17th century but expanded for industrial output.[27][28][29] Population growth reflected these developments, rising from 4,160 in 1801 to 14,281 by 1851, exceeding 15,000 by 1901, as migrant workers filled expanding workforces in mines and forges. This artisan-based economy fostered innovations like water- and steam-powered machinery, yet census data and contemporary accounts reveal harsh conditions, including precarious employment for nailers—estimated at around 50,000 regionally by mid-century—who endured low wages, irregular work, and descriptions as among England's "most immoral" laborers due to poverty-driven hardships.[30][31]20th and 21st centuries

The coal mining sector in Wednesbury and the surrounding Black Country experienced significant closures during the 1960s, as part of broader post-war rationalization efforts by the National Coal Board, which deemed many pits uneconomical amid mechanization and shifting energy demands.[32] This marked the end of deep coal extraction in the locality, contributing to early signs of industrial contraction. Similarly, the steel industry, a cornerstone of local manufacturing, faced contraction from the 1970s onward due to intensified global competition from lower-cost producers in Asia and internal factors including frequent union-led disruptions and inefficiencies stemming from the 1967 nationalization of British Steel, which prioritized employment preservation over productivity enhancements.[33][34] Local examples included substantial job losses at firms like Patent Shaft, with 1,500 redundancies announced in 1982 amid the British Steel Corporation's restructuring.[35] These developments, compounded by over-reliance on heavy industry without timely diversification, drove unemployment in the West Midlands region to peaks around 13% during the early 1980s recession, with Wednesbury sharing in the acute local impacts.[36] Post-war policies, including nationalization and expansive welfare provisions, inadvertently prolonged structural vulnerabilities by discouraging agile adaptation to market signals, as evidenced by persistent overmanning and investment shortfalls in state-controlled entities.[37] Narratives attributing decline solely to external forces overlook these domestic policy shortcomings, which causal analysis reveals amplified the effects of globalization; for instance, union actions in the late 1970s disrupted production, eroding competitiveness against non-unionized foreign rivals. Empirical data from the period underscore that UK steel output stagnated while global production expanded, highlighting failures in modernization under public ownership.[33] In the 21st century, regeneration initiatives have sought to address these legacies through town center revitalization, including the Wednesbury Masterplan and improvements to public spaces funded by UK government and EU sources, alongside developments like the Gallagher Retail Park to bolster retail and light industry.[38][39] Outcomes remain mixed, with ongoing projects like frontage enhancements and infrastructure upgrades showing partial success in enhancing attractiveness, yet persistent economic challenges per Office for National Statistics data indicate limited reversal of deprivation metrics.[40] The 2021 Census reflects a broader shift toward the service sector in England and Wales, with employment growth in areas like health and social work, mirroring Wednesbury's transition away from manufacturing dominance, though manufacturing retains a foothold in the Black Country economy.[41] This evolution underscores the necessity of diversified economic bases to mitigate risks exposed by prior mono-industrial dependence.Transport evolution

The Wednesbury Old Canal, engineered by James Brindley under the Birmingham Canal Navigations Act of 1768, entered service in 1769, forming a critical link from Wednesbury to Birmingham via the Bradley Arm and Wednesbury Oak Loop.[42] This infrastructure directly enabled the export of locally abundant coal and iron from Wednesbury's mines and forges to broader markets, while allowing imports of limestone and other raw materials essential for ironworking, thereby accelerating the area's industrial takeoff during the late 18th century.[43] Rail connectivity arrived with the Grand Junction Railway's opening on July 4, 1837, which skirted Wednesbury en route from Birmingham to Warrington, initially served by Bescot station approximately two miles north.[44] The line facilitated bulk transport of heavy goods like coal and finished iron products at speeds and volumes unattainable by canal, importing raw materials such as ore from distant regions and sustaining Wednesbury's chain-making and tube-manufacturing sectors through enhanced supply chain efficiency. Subsequent developments included the Great Western Railway's extension to Wednesbury by 1865, establishing Wednesbury Town station to handle local passenger and freight traffic.[45] Post-World War II shifts prioritized road infrastructure, with the M6 motorway's completion in the 1960s-1970s positioning Wednesbury adjacent to Junction 9, promoting freight haulage by truck and reducing reliance on aging rail and canal networks. However, the 1963 Beeching Report's recommendations led to Wednesbury Town station's closure on January 18, 1964, severing direct passenger rail access and exemplifying broader cuts that dismantled over 40% of Black Country lines, which critics contend inflicted long-term economic damage by isolating communities from labor markets and eroding freight competitiveness against road dominance.[46] Recent light rail initiatives, including West Midlands Metro extensions branching from Wednesbury Great Western Street stop since 1999, have partially restored connectivity along disused corridors, underscoring rail's enduring role in mitigating prior disruptions.[47]Governance

Local administration

Wednesbury has been governed as part of the Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council (MBC) since 1 April 1974, following the abolition of its independent municipal borough status under the Local Government Act 1972, which merged it with the boroughs of West Bromwich and Smethwick and portions of other districts to form the larger metropolitan borough. Prior to this, Wednesbury operated as a municipal borough from 1886, with its own elected council managing local affairs independently.[8] Sandwell MBC holds principal authority over Wednesbury's local services, including spatial planning, social housing provision, and waste collection, with decisions centralized at the borough level rather than town-specific.[48][49][50] The council's 72 members are elected from 24 wards, with the Labour Party securing 64 seats after the 2 May 2024 elections, maintaining its long-standing control and influencing policy priorities such as budget allocation and service delivery.[51] Financially, Sandwell MBC's operations in Wednesbury depend on a mix of revenues, with approximately 40% from council tax, 56% from retained business rates, and 4% from non-specific central government grants, though specific grants for areas like social care supplement this, totaling £55.391 million in 2025/26 amid ongoing fiscal pressures from historic grant reductions.[52][53] This structure reflects a shift from Wednesbury's pre-1974 self-contained fiscal autonomy to integrated borough-wide funding, where local precepts fund shared services but limit town-level discretion.[52]Electoral wards and districts

Wednesbury falls within three wards of Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council: Friar Park, Wednesbury North, and Wednesbury South, each electing three councillors to represent local interests in planning, community services, and infrastructure decisions.[54][55][56] These wards encompass the town's core areas, with boundaries reviewed periodically by the Local Government Boundary Commission for England to ensure electoral equality, as implemented in recent adjustments effective from 2024.[57] According to the 2021 Census, Friar Park ward had a population of 12,793, Wednesbury North 13,319, and Wednesbury South approximately 15,227, collectively forming the bulk of Wednesbury's 41,335 residents and highlighting denser urban settlement in the north and south wards.[1][58] Each ward's councillors, as of the 2024 local elections, are affiliated with the Labour Party, reflecting the party's longstanding control in Sandwell with 64 of 72 seats council-wide.[59][60] Sub-areas such as Oakeswell End within Wednesbury South function as localized districts for targeted community representation, informing ward-level planning on issues like housing and green spaces, though they lack independent electoral status. Voter turnout in Wednesbury wards remains low, with Wednesbury South recording 26% in the 2024 election on 2,717 valid ballots, underscoring empirical challenges in civic engagement amid broader Sandwell trends of subdued participation.[61]Demographics

Population statistics

According to the 2001 United Kingdom census, the population of Wednesbury—defined by its North and South electoral wards—totalled 23,950 residents.[58][62] This figure rose to 25,192 by the 2011 census, reflecting a 5.2% increase over the decade, before climbing further to 28,545 in the 2021 census, a 13.4% rise from 2011.[58][62] Overall, the population grew by 19.3% between 2001 and 2021, indicating steady urban expansion amid regional trends in the West Midlands.[58][62]| Census Year | Wednesbury North Ward | Wednesbury South Ward | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 11,728 | 12,222 | 23,950 |

| 2011 | 12,682 | 12,510 | 25,192 |

| 2021 | 13,319 | 15,226 | 28,545 |