Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stuckism

View on Wikipedia

Stuckism (/ˈstʌkɪzəm/) is an international art movement founded in 1999 by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson to promote figurative painting as opposed to conceptual art.[2][3] By May 2017, the initial group of 13 British artists had expanded to 236 groups in 52 countries.[4]

Key Information

Childish and Thomson have issued several manifestos. The first one was The Stuckists, consisting of 20 points starting with "Stuckism is a quest for authenticity".[5] Remodernism, the other well-known manifesto of the movement, opposes the deconstruction and irony of postmodernism in favor of what Stuckists refer to as the "spirituality" of the artist.[6] In another manifesto they define themselves as anti-anti-art[7] which is against anti-art and for what they consider conventional art.[8]

After exhibiting in small galleries in Shoreditch, London, the Stuckists' first show in a major public museum was held in 2004 at the Walker Art Gallery, as part of the Liverpool Biennial. The group has demonstrated annually at Tate Britain against the Turner Prize since 2000, sometimes dressed in clown costumes. They have also come out in opposition to the Charles Saatchi-patronised Young British Artists.[9][10]

Although painting is the dominant artistic form of Stuckism, artists using other media such as photography, sculpture, film and collage have also joined, and share the Stuckist opposition to conceptualism and "ego-art."[11]

Name, founding and origin

[edit]

The name "Stuckism" was coined in January 1999 by Charles Thomson in response to a poem read to him several times by Billy Childish. In it, Childish recites that his former girlfriend, Tracey Emin had said he was "stuck! stuck! stuck!" with his art, poetry and music.[12] Later that month, Thomson approached Childish with a view to co-founding an art group called Stuckism, which Childish agreed to, on the basis that Thomson would do the work for the group, as Childish already had a full schedule.[12]

There were eleven other founding members: Philip Absolon, Frances Castle, Sheila Clark, Eamon Everall, Ella Guru, Wolf Howard, Bill Lewis, Sanchia Lewis, Joe Machine, Sexton Ming, and Charles Williams.[12] The membership has evolved since its founding through creative collaborations:[13] the group was originally promoted as working in paint, but members have since worked in various other media, including poetry, fiction, performance, photography, film and music.[12]

In 1979, Thomson, Childish, Bill Lewis and Ming were members of the Medway Poets performance group, to which Absolon and Sanchia Lewis had earlier contributed.[12] Peter Waite's Rochester Pottery staged a series of solo painting shows.[12] In 1982, TVS broadcast a documentary on the poets.[12] That year, Emin, then a fashion student, and Childish started a relationship; her writing was edited by Bill Lewis, printed by Thomson and published by Childish.[12] Group members published dozens of works.[12] The poetry group dispersed after two years, reconvening in 1987 to record The Medway Poets LP.[12] Clark, Howard and Machine became involved over the following years.[12] Thomson got to know Williams, who was a local art student and whose girlfriend was a friend of Emin; Thomson also met Everall.[12] During the foundation of the group, Ming brought in his girlfriend, Guru, who in turn invited Castle.[12]

Manifestos

[edit]

In August 1999, Childish and Thomson wrote The Stuckists manifesto[5] which stress the value of painting as a medium, its use for communication, and the expression of emotion and experience – as opposed to what Stuckists see as the superficial novelty, nihilism and irony of conceptual art and postmodernism. The most contentious statement in the manifesto is: "Artists who don't paint aren't artists".[14]

The second and third manifestos, An Open Letter to Sir Nicholas Serota and Remodernism respectively, were sent to the director of the Tate, Nicholas Serota. He sent a brief reply: "Thank you for your open letter dated 6 March. You will not be surprised to learn that I have no comment to make on your letter, or your manifesto 'Remodernism'."[15]

In the Remodernism manifesto, the Stuckists declared that they aimed to replace postmodernism with remodernism, a period of renewed spiritual (as opposed to religious) values in art, culture and society. Other manifestos have included Handy Hints, Anti-anti-art, The Cappuccino writer and the Idiocy of Contemporary Writing, The Turner Prize, The Decreptitude of the Critic and Stuckist critique of Damien Hirst.

In Anti-anti-art, the Stuckists outlined their opposition to what is known as "anti-art".[8] Stuckists claim that conceptual art is justified by the work of Marcel Duchamp, but that Duchamp's work is "anti-art by intent and effect". The Stuckists feel that "Duchamp's work was a protest against the stale, unthinking artistic establishment of his day", while "the great (but wholly unintentional) irony of postmodernism is that it is a direct equivalent of the conformist, unoriginal establishment that Duchamp attacked in the first place".[16]

Manifestos have been written by other Stuckists, including the Students for Stuckism group. An "Underage Stuckists" group was founded in 2006 with a manifesto for teenagers written by two 16-year-olds, Liv Soul and Rebekah Maybury, on MySpace.[17] In 2009, a group calling itself the Other Muswell Hill Stuckists published The Founding, Manifesto and Rules of the Other Muswell Hill Stuckists.[18]

Growth in the UK

[edit]

In July 1999, the Stuckists were first mentioned in the media, in an article in The Evening Standard and soon gained other coverage, helped by press interest in Tracey Emin, who had been nominated for the Turner Prize.[19][20]

The first Stuckist show was Stuck! Stuck! Stuck! in September 1999 in Joe Crompton's in Shoreditch Gallery 108 (now defunct), followed by The Resignation of Sir Nicholas Serota. In 2000, they staged The Real Turner Prize Show at the same time as the Tate Gallery's Turner Prize exhibition.[21]

A "Students for Stuckism" group was founded in 2000 by students from Camberwell College of Arts, who staged their own exhibition. S.P. Howarth was expelled from the painting degree course at Camberwell college for his paintings,[22] and had the first solo exhibit at the Stuckism International Gallery in 2002, named I Don't Want a Painting Degree if it Means Not Painting.[23]

Thomson stood as a Stuckist candidate for the 2001 British General Election, in the constituency of Islington South & Finsbury, against Chris Smith, the then Secretary of State for Culture. He picked up 108 votes (0.4%).[24][25] Childish left the group at this time because he objected to Thomson's leadership.[26][27]

From 2002 to 2005, Thomson ran the Stuckism International Centre and Gallery in Shoreditch, London. In 2003, under the title A Dead Shark Isn't Art, the gallery exhibited a shark which had first been put on public display in 1989 (two years before Damien Hirst's) by Eddie Saunders in his Shoreditch shop, JD Electrical Supplies. It was suggested that Hirst may have seen this and copied it.[28]

In 2003, they reported Charles Saatchi to the UK Office of Fair Trading, complaining that he had an effective monopoly on art. The complaint was not upheld.[29] In 2003, an allied group, Stuckism Photography, was founded by Larry Dunstan and Andy Bullock. In 2005, the Stuckists offered a donation of 175 paintings from the Walker show to the Tate; however, it was rejected by the Tate's trustees.[30]

In August 2005, Thomson alerted the press to the fact that the Tate had purchased a work by Chris Ofili, The Upper Room, for £705,000 while the artist was a serving Tate trustee.[31][32] Fraser Kee Scott, owner of A Gallery, demonstrated with the Stuckists outside the Tate Gallery against the gallery's purchase of The Upper Room. Scott said in The Daily Telegraph that the Tate Gallery's chairman, Paul Myners, was hypocritical for refusing to divulge the price paid. Ofili had asked other artists to donate work to the gallery.[33] In July 2006 the Charity Commission censured the gallery for acting outside its legal powers.[34] Sir Nicholas Serota stated that the Stuckists had "acted in the public interest".[35]

In October 2006, the Stuckists staged their first exhibition, Go West, in a commercial West End gallery, Spectrum London;[36] this signalled their entry as "major players" in the art world.[37]

An international symposium on Stuckism took place in October 2006 at the Liverpool John Moores University during the Liverpool Biennial. The programme was led by Naive John, founder of the Liverpool Stuckists. There was an accompanying exhibition in the 68 Hope Gallery at Liverpool School of Art and Design (John Moores University Gallery).[38]

By 2006, there were 63 Stuckist groups in the UK. Members include Naive John, Mark D, Elsa Dax, Paul Harvey, Jane Kelly, Udaiyan, Peter McArdle, Peter Murphy, Rachel Jordan, Guy Denning and Abby Jackson. John Bourne opened Stuckism Wales at his home, a permanent exhibition of (mainly Welsh) paintings. Mandy McCartin is a regular guest artist.[39]

In 2010, Paul Harvey's painting of Charles Saatchi was banned from the window display of the Artspace Gallery in Maddox Street, London, on the grounds that it was "too controversial for the area".[40][41] It was the centrepiece of the show, Stuckist Clowns Doing Their Dirty Work, the first exhibition of the Stuckists in Mayfair,[41] and depicted Saatchi with a sheep at his feet and a halo made from a cheese wrapper.[42] The Saatchi Gallery said that Saatchi "would not have any problem" with the painting's display.[42] The gallery announced they were shutting down the show.[41] Harvey said, "I did it to make Saatchi look friendly and human. It's a ludicrous decision".[42] The Stuckists protested with emails to the gallery.[43] Subsequently, the painting was reinstated and the show continued.[43]

Demonstrations

[edit]

The Stuckists gained significant media coverage for eight years of protests (2000–2006 and 2008) outside Tate Britain against the Turner Prize, sometimes dressed as clowns. In 2001, they demonstrated in Trafalgar Square at the unveiling of Rachel Whiteread's Monument. In 2002, they carried a coffin marked The Death of Conceptual Art to the White Cube Gallery.[44][45] Outside the launch of The Triumph of Painting at the Saatchi Gallery in 2004, they wore tall hats with Charles Saatchi's face emblazoned; they also carried placards claiming that Saatchi had copied their ideas.[46]

Events outside Britain have included The Clown Trial of President Bush held in New Haven in 2003 to protest against the Iraq War. Michael Dickinson has exhibited political and satirical collages in Turkey for which he was arrested,[47] and charged, but acquitted of any crime—an outcome which was seen to have positive implications for Turkey's relationship with the European Union.[48]

The Stuckists Punk Victorian

[edit]The Stuckists Punk Victorian was the first national gallery exhibition of Stuckist art. It was held at the Walker Art Gallery and Lady Lever Art Gallery and was part of the 2004 Liverpool Biennial. It consisted of over 250 paintings by 37 artists, mostly from the UK but also with a representation of international Stuckist artists from the US, Germany and Australia. There was an accompanying exhibition of Stuckist photographers. A book, The Stuckists Punk Victorian, was published to accompany the exhibition. Daily Mail journalist Jane Kelly exhibited a painting of Myra Hindley in the show, which may have been the cause of her dismissal from her job.[49]

A Gallery

[edit]

In July 2007, the Stuckists held an exhibition at A Gallery, I Won't Have Sex with You as long as We're Married,[50][51] titled after words apparently said to Thomson by his ex-wife, Stella Vine on their wedding night.[51] The show coincided with the opening of Vine's major show at Modern Art Oxford and was prompted by Thomson's anger that the material promoting her show did not mention her time with the Stuckists.[50] Tate chairman Paul Myners visited both shows.[52]

Sir Nicholas Serota Makes an Acquisitions Decision

[edit]

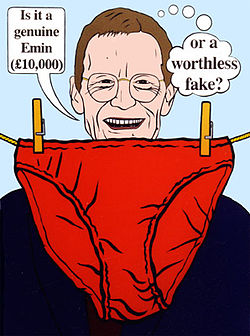

As Charlotte Cripps of The Independent wrote, Charles Thomson's painting Sir Nicholas Serota Makes an Acquisitions Decision is one of the best known paintings to come out of the Stuckist movement,[45] and as Jane Morris wrote in The Guardian it's a likely "signature piece" for the movement,[53] standing for its opposition to conceptual art. Painted in 2000, the piece has been exhibited in later Stuckist shows, and featured on placards in Stuckist demonstrations against the Turner Prize. It depicts Sir Nicholas Serota, Director of the Tate Gallery and the usual chairman of the Turner Prize jury, and satirises Young British Artist Tracey Emin's installation, My Bed, consisting of her bed and objects, including knickers, which she exhibited in 1999 as a Turner Prize nominee.[54]

International movement

[edit]In 2000, Regan Tamanui started the first Stuckist group outside Britain in Melbourne, Australia, and it was decided that other artists should be free to start their own groups also, named after their locality.[55] Stuckism has since grown into an international art movement[2] of 233 groups in 52 countries, as of July 2012.[4]

Africa

[edit]Mafa Bamba founded the Abidgan Stuckists in 2001 in Ivory Coast and Kari Seid founded the Cape Town Stuckists in 2008 in South Africa.[56]

America

[edit]

In 2000, Susan Constanse founded the first U.S. group the Pittsburgh Stuckists in Pittsburgh[56]—the second group to be founded outside the UK. This was announced in the In Pittsburgh Weekly, 1 November 2000: "The new word in art is Stuckism. A Stuckist paints their life, mind and soul with no pretensions and no excuses."[57] By 2011, there were 44 U.S. Stuckist groups. There have been Stuckist shows and demonstrations in the U.S., and American Stuckists have also exhibited in international Stuckist shows abroad. U.S. Stuckists include Ron Throop, Jeffrey Scott Holland, Frank Kozik and Terry Marks.[56] There are also 4 Stuckist groups in Canada including the White Rock Stuckists in British Columbia founded by David Wilson.[56]

Asia

[edit]Asim Butt founded the first Pakistani Stuckist group, the Karachi Stuckists, in 2005.[58] At the end of 2009 he was thinking of expanding the Karachi Stuckists with new members;[59] however, on 15 January 2010 he committed suicide.[60] In 2011, Sheherbano Husain restarted the group.[56]

The Tehran Stuckists is an Iranian Stuckist, Remodernist and anti-anti-art group of painters founded in 2007 in Tehran,[56] which is a major protagonist of Asian Stuckism.[11] In April 2010 they curated the first Stuckist exhibition in Iran, Tehran Stuckists: Searching for the Unlimited Potentials of Figurative Painting, at Iran Artists Forum, Mirmiran Gallery.[61] Their second exhibition, International Stuckists: Painters Out of Order, including paintings by Stuckists from Iran, Britain, USA, Spain, South Africa, Pakistan and Turkey was held at Day Gallery in November 2013.[62] Although one of the main aspects of Stuckism movement is that "the Stuckist allows him/herself uncensored expression";[5] however, the Tehran Stuckists exhibitions in Iran are censored and they are not allowed to exhibit some of their artworks in Iranian galleries.[63] The group has also participated in Stuckist exhibitions in Britain, Lithuania and Spain.[61]

Other Asian Stuckists are Shelley Li (China), Smeetha Boumik (India), Joko Apridinoto (Indonesia), Elio Yuri Figini (Japan) and Fady Chamaa (Lebanon).[56]

Europe

[edit]

The Prague Stuckists were founded in 2005 in the Czech Republic by Robert Janás,[56][64] Other Stuckist artists in Europe include Peter Klint (Germany), Michael Dickinson (Turkey), Odysseus Yakoumakis (Greece), Artista Eli (Spain), Kloot Per W (Belgium), Jaroslav Valečka (Czech Republic), Jiří Hauschka (Czech Republic),[65] Markéta Korečková (Czech Republic), Ján Macko (Slovakia) and Pavel Lefterov (Bulgaria).[56]

Oceania

[edit]In October 2000, Regan Tamanui founded the Melbourne Stuckists in Melbourne,[66] the fourth Stuckist group to be started and the first one outside the UK. On 27 October 2000, he staged the Real Turner Prize Show at the Dead End Gallery in his home, concurrent with three shows with the same title in England (London, Falmouth and Dartington) and one in Germany in protest against the Tate Gallery's Turner Prize. Other Australian Stuckists include Godfrey Blow, who exhibited in The Stuckists Punk Victorian.[67] In 2005 Mike Mayhew also founded the Christchurch Stuckists in New Zealand.[56]

Ex-Stuckists

[edit]Co-founder Billy Childish left the group in 2001, but has stated that he remains committed to its principles. Sexton Ming left to concentrate on a solo career with the Aquarium Gallery. Wolf Howard left in 2006, but has exhibited with the group since. Jesse Richards who ran the Stuckism Centre USA in New Haven, left the group in 2006 to focus on Remodernist film.

In June 2000, Stella Vine went to a talk given by Childish and Thomson on Stuckism and Remodernism in London.[69] At the end of May 2001, she exhibited some of her paintings publicly for the first time in the Vote Stuckist show in Brixton, and formed the Westminster Stuckists group.[68] On 4 June, she took part in a Stuckist demonstration in Trafalgar Square.[69][70] By 10 July, she had renamed her group the Unstuckists.[71] In mid-August, Thomson and Vine married.[72] A work by her was shown in the Stuckist show in Paris, which ended in mid-November, by which time she had rejected the Stuckists,[68] and the marriage had ended.

In February 2004, Charles Saatchi bought a painting of Diana, Princess of Wales, by Vine and was credited with "discovering" her. Thomson said it was the Stuckists and not Saatchi who had discovered her.[73] At the end of March 2004, Thomson made a formal complaint about Saatchi to the Office of Fair Trading, claiming that Saatchi's leading position was monopolistic "to the detriment of smaller competitors",[74] citing Vine as an example of this.[75] On 15 April, the OFT closed the file on the case on the basis that Saatchi was not "in a dominant position in any relevant market."[76]

Responses and critique

[edit]A short time after the 1999 exhibition of My Bed and the Stuckists' response with Sir Nicholas Serota Makes an Acquisitions Decision, a pair of performance artists named Yuan Cai and Jian Jun Xi performed an art intervention titled Two Naked Men Jump into Tracey's Bed at the Tate Gallery's Turner Prize. Cai had written, among other things, the words "Anti Stuckism" on his bare back as the two jumped on the bed and performed a pillow fight. Fiachra Gibbons of The Guardian wrote (in 1999) that the event "will go down in art history as the defining moment of the new and previously unheard of Anti-Stuckist Movement."[77] Writing in The Guardian ten years later, Jonathan Jones described the Stuckists as "enemies of art", and what they say as "cheap slogans" and "hysterical rants".[78]

The artist Max Podstolski wrote that the art world needed a new manifesto, as confrontational as that of Futurism or Dadaism, "written with a heart-felt passion capable of inspiring and rallying art world outsiders, dissenters, rebels, the neglected and disaffected", and suggests that "Well now we've got it, in the form of Stuckism".[79]

New York art gallery owner Edward Winkleman wrote in 2006 that he had never heard of the Stuckists, so he "looked them up on Wikipedia", and stated he was "turned off by their anti-conceptual stance, not to mention the inanity of their statement about painting, but I'm more than a bit interested in the democratization their movement represents." Thomson responded to Winkleman directly.[80]

Also in 2006, Colin Gleadell, writing in The Telegraph, noted that the Stuckists' first exhibition in central London had brought "multiple sales" for leading artists of the movement, and that this raised the question of how good they were at painting. He observed that "Whatever the critics may say, buyers from the UK, the US and Japan have already taken a punt. Six of Thomson's paintings have sold for between £4,000 and £5,000 each. Joe Machine, a former prisoner who paints for therapeutic reasons, has also sold six paintings for the same price."[81]

Paul Vallely defended Sir Nicholas Serota from Stuckist campaigns, criticizing the movement's anti-conceptualism for its association with "forces of social reaction" such as the Daily Mail and upholding Serota as the "greatest single champion of modern art in Britain".[82] Vallely stated that while "I did smile" at Acquisitions Decision, he equally admired Serota's "cool response to the Stuckist détournement", visiting the Punk Victorian show and conversing with members before rejecting an offered donation of their work as not of "sufficient quality in terms of accomplishment, innovation or originality of thought to warrant preservation in perpetuity in the national collection".[82]

The BBC arts correspondent Lawrence Pollard wrote in 2009 that the way was paved for "cultural agitators" like the Stuckists, as well as the Vorticists, Surrealists and others, by the Futurist Manifesto of 20 February 1909.[83]

Gallery

[edit]Some UK Stuckist artists' work:

-

Philip Absolon. Breakdown (uploaded 2008, date of creation not known)

-

John Bourne. Epsom Kitchen (uploaded 2008)

-

Mark D. Victoria Beckham: America Doesn't Love Me (uploaded 2008)

-

Elsa Dax. Bacchus (uploaded 2008)

-

Eamon Everall. The Marriage (uploaded 2008)

-

Ella Guru. Goodbye Columbus, (uploaded 2008)

-

Paul Harvey. Ford Anglia with Tent and Giotto Tree (uploaded 2008)

-

Jane Kelly. If We Could Undo Psychosis 1 (uploaded 2008)

-

Bill Lewis. The Laughter of Small White Dogs (uploaded 2008)

-

Joe Machine. Diana Dors with an Axe (uploaded 2008)

-

Peter McArdle. Artist and Model (uploaded 2008)

-

Charles Thomson. A Single Woman in London Is Never more than Six Inches from the Nearest Rat (uploaded 2008)

See also

[edit]- List of Stuckist artists

- List of Stuckist shows

- Remodernism – Present-day modernist philosophical movement

- Dogme 95 – Danish filmmaking movement

- Neomodernism – Philosophical movement

- New Puritans – Literary movement

- Wesley Kimler – American painter (anti-conceptual artist)

References

[edit]- ^ "Origins Of Stuckism", staff writer, September 1999 Accessed 11 April 2006

- ^ a b "Glossary: Stuckism", Tate. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ "The Stuckists Punk Victorian", Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Stuckism International", stuckism.com. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ a b c The Stuckists manifesto, stuckism.com. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ Art Glossary: Remodernism Archived 20 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, about.com. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "Stuck on the Turner Prize", artnet, 27 October 2000. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ a b Childish, Billy; Thomson, Charles (4 November 2000). "Anti-anti-art". stuckism.com.

- ^ Stuckism, Artist Biographies website.

- ^ The Turner Prize's most controversial moments, 20 October 2011, The Telegraph website.

- ^ a b "Stuckism International: The Stuckist Decade 1999–2009", Robert Janás, Victoria Press Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 2009, a: p.73 - b: p.64, ISBN 0-907165-28-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Thomson, Charles (August 2004), "A Stuckist on Stuckism: Stella Vine", from: Ed. Frank Milner (2004), The Stuckists Punk Victorian, pp. 7–9, National Museums Liverpool, ISBN 1-902700-27-9. Available online at "The Two Starts of Stuckism" and "The Virtual Stuckists" on stuckism.com.

- ^ "Stuckism: Introduction", stuckism.com. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Stuckists, scourge of BritArt, put on their own exhibition Sarah Cassidy, The Independent, 23 August 2006,

- ^ "An open letter to Sir Nicholas Serota", stuckism.com, 1999. Retrieved 20 May 2007

- ^ "Stuckism : Art Against Art Against Art". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "The Underage Stuckists Manifesto", stuckism.com. Retrieved 25 April 2006

- ^ Danchev, Alex (2011). 100 Artists' Manifestos: From the Futurists to the Stuckists. Penguin Books. p. 537. ISBN 978-0-14-193215-6.

- ^ Stuckism news 1999, stuckism.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Aitch, Iain (23 November 1999). "Dirty Laundry Brit Artists Tracey Emin and Billy Childish go very public". Whoa!. Archived from the original on 4 November 2002. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Turner Prize: a load of rubbish?, London Evening Standard, 24 October 2000. Retrieved 30 August 2011. Archived 14 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alberge, Dalya, "Students accuse art college of failing to teach them the basics", The Times, p. 9, 8 July 2002. Online at stuckism.com.

- ^ S.P. Howarth, stuckism.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Vote Stuckist 2001, stuckism.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Vote 2001, Islington South & Finsbury, BBC. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Billy Childish On Stuckism, April 2004, trakmarx.com. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Billy Childish, stuckism.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "A Dead Shark Isn't Art", stuckism.com. Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- ^ "Charles Saatchi reported to OFT", stuckism.com. Retrieved 27 May 2006

- ^ How ageing art punks got stuck into Tate's Serota, The Guardian, 11 December 2005. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ How ageing art punks got stuck into Tate's Serota, The Guardian, 11 December 2005.

- ^ "Tate buys trustee Chris Ofili's The Upper Room in secret £705,000 deal", stuckism.com. Retrieved 27 May 2006

- ^ Walden, Celia. "Spy: Art-felt grumble", The Daily Telegraph, p. 22, 19 October 2008.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (2006) "Tate's Ofili purchase broke charity law" The Times online, 19 July 2006. Retrieved 8 April 2007

- ^ Front Row, BBC Radio 4, interview by Mark Lawson, 25 July 2006

- ^ Barnes, Anthony (2006) "Portrait of an ex-husband's revenge" The Independent on Sunday. Retrieved 9 October 2006, from findarticles.com

- ^ Teodorczuk, Tom (2006) "Modern art is pants" London Evening Standard, 22 August 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2006 from thisislondon.co.uk. Archived 17 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Day 13th Oct "International Symposium on Stuckism", Independents Liverpool Biennial. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ Mandy McCartin, stuckism.com. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "Mr Saatchi in the frame" Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, London Evening Standard, 24 August 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b c "Charles Saatchi painting gets Stuckists shut down", Spoonfed Media, 25 August 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010. Archived 12 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Wilkinson, Tara Loader."Mayfair divided over Charles Saatchi cheese painting", Financial News, 26 August 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b Carmichael, Kim. "Painting by North East artist sparks row in art world" Archived 17 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine, The Journal, 28 August 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "White Cube Demo 2002", stuckism.com. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ a b Cripps, Charlotte. "Visual arts: Saying knickers to Sir Nicholas, The Independent, 7 September 2004. Retrieved from findarticles.com, 7 April 2008.

- ^ Painting by North East artist sparks row in art world Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Journal, 28 August 2010.

- ^ Birch, Nicholas. "Briton charged over 'insult' to Turkish PM", The Guardian, 13 September 2006. Retrieved 2 September 2007.

- ^ Tait, Robert. "Turkish court acquits British artist over portraying PM as US poodle", The Guardian, 26 September 2008. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ Wells, Matt and Cozens, Claire. "Daily Mail sacks writer who painted Hindley picture", The Guardian, 30 September 2004. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ a b Duff, Oliver. "Stuckists prune Vine", The Independent, 5 June 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ a b Moody, Paul. "Everyone's talking about Stella Vine", The Guardian, 12 July 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- ^ Duff, Oliver. "Legal sharks circle round Davis and his chief of staff", (3rd story), The Independent, 27 July 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ Morris, Jane. "Getting stuck in", The Guardian, 24 August 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ Cassidy, Sarah. "Stuckists, scourge of BritArt, put on their own exhibition" Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 23 August 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ Thomson, Charles, "A Stuckist on Stuckism" in: Milner, Frank, ed. The Stuckists Punk Victorian, p.20, National Museums Liverpool 2004, ISBN 1-902700-27-9. Essay available online at stuckism.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Stuckist groups", stuckism.com. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ The Stuckists in the Media. The document lists articles in newspapers and magazines from Britain, Cyprus, Germany, Scotland, Switzerland, United Arab Emirates, United States. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ INSTEP Magazine, jang.com. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Asim's tribute page, stuckism.com. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Pakistan Daily Times, Daily Times, 16 January 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ a b Exhibitions - Tehran Stuckists, Tehran Stuckists website. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ International Exhibition of Works of Stuckist Artists in Tehran Archived 8 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Tehran Municipality website. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ^ "Articles about Art 2": Analytic Study of Stuckism Movement in Paintings (in Persian), Tayebeh Rouzbahani, page 237, Daryabeygi publications Archived 19 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 2014, ISBN 978-600-93925-2-0.

- ^ Charles Thomson, Robert Janás, Edward Lucie-Smith, "The Enemies of Art: The Stuckists" (2011), p. 8, Victoria Press Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0-907165-31-6.

- ^ Edward Lucie-Smith, "Stuck Between Prague and London: Paul Harvey Jiri Hauschka Edgeworth Johnstone Charles Thomson Jaroslav Valecka" (2013), Victoria Press Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0-907165-33-0. As available on Amazon.co.uk.

- ^ "International Stuckists", Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ^ "Godfrey Blow", Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 15 November 2008. Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Thomson, Charles (August 2004), "A Stuckist on Stuckism: Stella Vine", from: Ed. Frank Milner (2004), The Stuckists Punk Victorian, p. 23, National Museums Liverpool, ISBN 1-902700-27-9. Available online at stuckism.com.

- ^ a b "Stella Vine the Stuckist in photos", stuckism.com. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "New sculpture in London's Trafalgar Square", Getty Images, 4 June 2001. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ Stuckism news: Westminster Stuckists come unstuck", stuckism.com, 10 July 2001. Retrieved from Internet Archive, 9 January 2009.

- ^ "Trouble and strife", London Evening Standard, p. 12, 20 August 2001.

- ^ Alleyne, Richard. "The 'Saatchi effect' has customers queueing for new artist", The Daily Telegraph, 28 February 2004. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- ^ Stummer, Robin. "Charles Saatchi 'abuses his hold on British art market'", The Independent on Sunday, 28 March 2004. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- ^ Renton, Andrew. "Artists' licence; Collector Charles Saatchi, artist Tracey Emin and painter Stella Vine have all been criticised for 'unfair' practices. But 'fairness' would kill art.", London Evening Standard, p. 41, 6 April 2004.

- ^ Charles Saatchi reported to OFT: OFT conclusion", stuckism.com. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ Gibbons, Fiachra (1999)"Satirists Jump into Tracey's Bed"The Guardian online, 25 October 1999. Retrieved 22 March 2006.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (2 October 2009). "The Stuckists are enemies of art". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Podstolski, Max (May 2002). "Head vs. Heart: a Critique of the Stuckist Manifesto". Spark-online. 32. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Winkleman, Edward (28 August 2006). "The Stuckists". Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Gleadell, Colin (3 October 2006). "Market news: Roger Hilton's child-like drawings, 'stuckist' paintings and Edward Seago". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b Vallely, Paul. "Tate that: Serota defies his critics", The Independent, 16 August 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2024

- ^ "Back to the Futurists". BBC. 20 February 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Ed. Katherine Evans, "The Stuckists", Victoria Press, 2000, ISBN 0-907165-27-3.

- Ed. Frank Milner, "The Stuckists punk Victorian", National Museums Liverpool, 2004, ISBN 1-902700-27-9.

- Robert Janás, "Stuckism International: The Stuckist Decade 1999–2009", Victoria Press, 2009, ISBN 0-907165-28-1.

- Charles Thomson, Robert Janás, Edward Lucie-Smith, "The Enemies of Art: The Stuckists", Victoria Press, 2011, ISBN 0-907165-31-1.

- Gabriela Luciana Lakatos, Expressionism Today (pages 13–14), University of Art and Design Cluj Napoca, 2011.

- Yolanda Morató, "¿Qué pinto yo aquí? Stuckistas, vanguardias remodernistas y el mundo del arte contemporáneo", Zut, 2006, ISSN 1699-7514 [It includes a translation into Spanish of Stuckism International and a portfolio of Larry Dunstan's pictures]

- Charles Thompson, "Stuck in the Emotional Landscape - Jiri Hauschka, Jaroslav Valecka", Victoria press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-907165-32-3.

External links

[edit]Stuckism

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Founding

Etymology and Initial Conception

The term "Stuckism" derives from an insult directed at painter Billy Childish by his former partner, the artist Tracey Emin, who in the early 1990s dismissed his figurative paintings as "stuck, stuck, stuck," implying they were outdated and rigid.[4][5] Charles Thomson, a fellow artist and collaborator with Childish, repurposed the phrase in 1999 to name the nascent movement, framing "stuck" not as creative stagnation but as steadfast adherence to authentic, personal expression through painting, in defiance of transient conceptual trends.[5] This etymology reflects the movement's roots in personal defiance against dismissive critiques from the emerging Young British Artists (YBAs) scene, of which Emin was a prominent figure.[4] Stuckism's initial conception crystallized in August 1999, when Childish and Thomson jointly authored The Stuckist Manifesto, a foundational text that articulated the movement's core tenets as a rebuke to conceptualism's dominance in British art institutions.[2] The manifesto emphasized painting's capacity for holistic communication—merging conscious intent with unconscious emotion—and rejected elitist, idea-driven art that prioritized novelty over sincerity, directly challenging the YBAs' conceptual focus and events like the 1997 Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy.[2][6] This document, self-published and circulated independently, marked Stuckism's emergence as a "remodernist" anti-anti-art stance, advocating for accessible, truth-seeking creativity amid what its founders saw as institutional corruption favoring shock value over substantive skill.[2] The conception drew from Childish's earlier punk-influenced Medway Poets group in Kent, where Thomson and others had already explored anti-establishment themes, but formalized into a visual art movement only after years of frustration with the Turner Prize and similar accolades.[6]Key Founders and Early Influences

Stuckism was co-founded in 1999 by Billy Childish, a multidisciplinary artist known for his work as a painter, poet, musician, and filmmaker, and Charles Thomson, a painter and former art lecturer.[1][7] The movement's name originated from a derogatory remark made by Childish's former partner, the artist Tracey Emin, who described his artistic style as "stuck," implying stagnation; Thomson adopted this term to embrace the idea of authenticity over fashionable novelty.[1] Childish departed from the group in 2001, after which Thomson became its primary leader.[1] The founders' collaboration drew from their shared background in the Medway Poets, a punk-influenced poetry and performance collective active in the Medway Towns area of Kent since the late 1970s, which emphasized raw expression and anti-establishment attitudes.[7][6] This scene, involving figures like Bill Lewis and Sexton Ming, fostered a DIY ethos that paralleled punk's rejection of elitism and informed Stuckism's advocacy for genuine, idea-driven figurative painting against conceptual art's perceived superficiality.[1] Early influences also included outsider art traditions, valuing unpolished, personal creativity over institutional approval, as seen in Childish's self-taught approach and Thomson's satirical works critiquing the art market.[7] The original Stuckist group consisted of 13 members, including Philip Absolon, Frances Castle, Sheila Clark, Eamon Everall, Ella Guru, Wolf Howard, Bill Lewis, Sanchia Lewis, Joe Machine, Sexton Ming, and Charles Williams, many of whom emerged from Medway's artistic undercurrents.[1] This foundational cohort held the first Stuckist exhibition in 1999, marking the movement's public debut as a direct response to the dominance of Young British Artists and events like the Turner Prize.[7]Core Ideology and Manifestos

The Stuckism Manifesto and Principles

The Stuckism Manifesto was co-authored by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson on August 4, 1999, establishing the core tenets of the art movement as a direct response to the perceived dominance of conceptual art and institutional elitism in the British art scene.[2] Published by The Hangman Bureau of Enquiry, the document comprises 20 statements that prioritize painting as an authentic medium of expression over conceptualism's emphasis on ideas detached from traditional techniques.[2] It derives its name from a derogatory remark by artist Tracey Emin to Childish—"Your paintings are stuck, you are stuck! Stuck! Stuck! Stuck!"—reclaiming the term to signify a deliberate embrace of unpolished, personal creativity rather than contrived novelty.[2] Central to the manifesto is the principle that "Stuckism is the quest for authenticity," positioning the movement as a rejection of postmodern fragmentation in favor of holistic art that integrates conscious and unconscious elements, thought and emotion, and spiritual and material aspects.[2] Painting is framed as the primary medium for self-discovery, with the assertion that "artists who don't paint aren't artists," underscoring a commitment to hands-on creation over theoretical or ready-made works, which are dismissed as materialistic and lacking inner depth.[2] The Stuckist artist is depicted as an amateur willing to take risks, focused on the process of painting rather than commercial prizes or career advancement, and embracing neurosis, innocence, and failure as pathways to genuine expression.[2] The manifesto critiques conceptual art and BritArt as ego-driven, state-sponsored phenomena that prioritize cleverness and subversion through institutional channels, such as galleries and high-profile endorsements, over substantive content.[2] It declares postmodernism a "cul-de-sac of idiocy" and calls for art that is alive, communicative, and international, free from jingoistic nationalism or anti-ism dogmatism.[2] Exhibitions should occur in accessible venues like homes or museums rather than sterile galleries, and art education must foster uncensored expression instead of bureaucratic conformity, advocating for open admissions policies.[2] Realism, content, humor, and the championing of process are elevated, with the Stuckist's role defined as being "wrong" in opposition to conceptualists' pursuit of being "right" or clever.[2] Influential historical figures are proposed as honorary Stuckists, including Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige, Vincent van Gogh, Edvard Munch, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff, Max Beckmann, and Kurt Schwitters, linking the movement to a lineage of expressive, idea-infused painting that transcends modernism's sterility.[2] These principles collectively aim to revive painting's vitality by grounding it in personal authenticity and public engagement, positioning Stuckism as a punk-inflected antidote to the commodified art world of the late 1990s.[2]Critiques of Conceptualism and Institutional Art

Stuckists argue that conceptual art privileges abstract ideas and novelty over skill, authenticity, and emotional resonance, resulting in works that prioritize shock or intellectual posturing at the expense of genuine creativity. In their foundational critique, co-founders Billy Childish and Charles Thomson contended that conceptualism's emphasis on the concept detached from execution enables the creation of superficial objects masquerading as profound, often reliant on curatorial interpretation for any perceived meaning rather than inherent artistic quality.[8] This separation, they asserted, fosters laziness among artists and commodifies art as an elite product, exemplified by Young British Artists (YBAs) such as Damien Hirst, whose formaldehyde-preserved shark The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) was dismissed as a "cumbersome poet with a rather excessive visual aid" purporting depth but delivering banality.[9][10] The movement further condemns institutional art establishments for entrenching conceptualism through monopolistic curation and public funding decisions that sidelined traditional painting. Charles Thomson criticized Charles Saatchi, the advertising magnate and YBA patron, for exerting undue influence over the British art market, effectively dictating tastes and suppressing competition from non-conceptual works by controlling gallery access and media hype.[11] Similarly, Stuckists targeted the Tate Gallery under director Sir Nicholas Serota, accusing it of institutional bias in acquiring overpriced YBA pieces—such as Hirst's works totaling millions—while rejecting donations of figurative paintings, including offers from Stuckist artists in the early 2000s.[12] Annual protests at the Turner Prize from 2000 onward highlighted this as an "ongoing embarrassment," with demonstrators decrying the award's promotion of conceptual installations as evidence of elitist gatekeeping that favored market-driven novelty over substantive art.[13] These critiques portray institutions not as neutral arbiters but as complicit in a cycle where conceptual art's dominance sustains high-value sales and insider networks, marginalizing artists committed to craftsmanship.[14]Emphasis on Authenticity, Figuration, and Anti-Elitism

Stuckism prioritizes authenticity in artistic creation, defining it as the uncensored expression of personal truth without reliance on conceptual detachment or intellectual posturing. The movement's foundational document asserts that "Stuckism is the quest for authenticity," achieved by artists removing "the mask of cleverness" to confront their immediate reality and emotions directly.[2] This principle, articulated by co-founders Billy Childish and Charles Thomson in 1999, rejects the artifice of irony or detachment prevalent in conceptual works, favoring instead raw, sincere output that reflects the artist's lived experience.[2] Central to this authenticity is a commitment to figuration, particularly through painting, as the primary medium for conveying human narrative and emotional depth. Stuckists advocate for "contemporary figurative painting with ideas," positioning it against the abstraction or object-based ephemera of conceptualism, which they view as evading genuine representation.[14] Figurative works by Stuckist artists, such as Eamon Everall's The Marriage (c. 2000s), exemplify this by depicting intimate, recognizable scenes that prioritize narrative clarity and personal symbolism over abstract experimentation.[14] This emphasis stems from the belief that figuration enables direct emotional veracity, allowing viewers to engage with art as a mirror of human conditions rather than esoteric theory.[15] Anti-elitism forms a core critique, targeting the institutional gatekeeping of bodies like the Tate Gallery and collectors such as Charles Saatchi, whom Stuckists accuse of promoting a "conceptual star system" that privileges novelty and commerce over substantive creativity.[16] The movement opposes this hierarchy by championing non-professional and outsider artists, arguing that authenticity thrives outside elite validation, as seen in their support for works embodying "spirituality found in non-professional art."[16] Thomson and Childish's 1999 manifesto explicitly denounces such elitism, calling for art to be accessible and rooted in universal human expression rather than curatorial endorsement.[2] This stance interconnects with authenticity and figuration by insisting that true art resists commodification, fostering instead a democratized practice where sincerity supplants status.[17]UK Development and Activities

Early Expansion and Domestic Groups

Following the inaugural Stuckist exhibition in September 1999, which featured works by ten of the thirteen founding artists, the movement expanded domestically through the establishment of independent regional groups in the United Kingdom.[1] This growth was fueled by the publication of the Stuckism Manifesto and early protests against institutional art, attracting artists disillusioned with conceptualism.[1] By 2000, affiliated groups had formed in locations such as Maidstone, with the Maidstone Stuckists organizing local activities.[1] Individual artists played key roles in nucleating early domestic outposts; for instance, Paul Harvey established a Stuckist presence in Newcastle, while Jane Kelly did so in Acton, London, emphasizing figurative painting in opposition to elite-dominated trends.[1] The Kingstone Stuckists, founded in 2000 by Charlotte Gavin, represented one of the first formalized subgroups outside the core London-Medway circle, focusing on authentic expression over conceptual abstraction.[18] Similarly, the Westminster Stuckists emerged in 2001 under Stella Vine, contributing to the movement's foothold in central London beyond the originators.[18] These nascent groups participated in parallel exhibitions, such as the Real Turner Prize Show in October 2000, which showcased anti-establishment works and drew media attention, further catalyzing recruitment.[1] Domestic expansion remained organic and decentralized, with groups maintaining autonomy while adhering to core principles of remodernism, leading to rapid proliferation across Britain by the early 2000s.[13]Protests, Demonstrations, and Campaigns

Stuckists conducted annual protests against the Turner Prize at Tate Britain starting in 2000, criticizing the award's emphasis on conceptual art over painting.[19] These demonstrations sought to expose what participants described as institutional corruption and the prioritization of novelty over artistic merit.[6] Protesters often wore clown costumes to symbolize the perceived absurdity of the contemporary art establishment.[20] The inaugural event, termed a "Clown Non-Demo," occurred on 28 November 2000, coinciding with the Turner Prize announcement; participants gathered silently outside the gallery.[19] In 2002, demonstrations took place on 29 October during the exhibition opening and on 8 December at the award ceremony, with Stuckists delivering manifestos and engaging media.[21] Similar actions followed in 2004, where the group highlighted Charles Saatchi's partial endorsement of painting while maintaining opposition to the prize's format.[22] Protests extended to critiques of specific Tate acquisitions, such as the 2005 demonstration against the purchase of Chris Ofili's The Upper Room installation, which Stuckists argued exemplified wasteful spending on conceptual works.[20] Beyond the Turner Prize, Stuckists targeted Charles Saatchi for promoting Young British Artists; on 20 October 2005, they demonstrated at the Saatchi Gallery in County Hall during the private view of The Triumph of Painting, distributing leaflets decrying his market influence.[23] As a parallel campaign, Stuckists launched the Real Turner Prize Show in 2000 as an alternative exhibition showcasing figurative painting, held annually to contrast with the official prize; the 2002 edition at the Stuckism International Gallery featured nominated artists and underscored their advocacy for authentic expression.[6][24] These efforts amplified Stuckism's message against conceptualism, though the group later reduced protests, noting the Turner Prize's diminished provocation by the mid-2010s.[25]Notable Exhibitions and Artworks

The inaugural Stuckist exhibition, titled "Stuck! Stuck! Stuck!", opened on 16 September 1999 at Gallery 108 on Leonard Street in Shoreditch, London, marking the public debut of the movement's collective works and principles.[26] This event featured paintings by the founding artists, emphasizing figurative styles in opposition to conceptual art.[27] In October 2000, the "Real Turner Prize Show" was staged at Pure Gallery in Shoreditch from 24 October to 28 November, presenting works by the initial group of 13 Stuckist artists as a direct counter to the Tate's Turner Prize.[26][19] The exhibition included paintings critiquing institutional art practices, with Charles Thomson's contributions highlighting themes of authenticity and anti-elitism.[6] A significant milestone occurred in 2004 with "The Stuckists Punk Victorian" exhibition at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, integrated into the Liverpool Biennial, which displayed over 250 paintings by 37 Stuckist artists from the UK and abroad.[6] This marked the first time Stuckist works entered a major national gallery collection, featuring pieces like Paul Harvey's Ford Anglia with Tent and Giotto Tree, which exemplifies the movement's focus on everyday subjects rendered in expressive, painterly techniques.[28][29] Other notable UK exhibitions include "Stuck! Paintings by the Stuckists" at the Metropole Arts Centre in Folkestone in 2000, showcasing regional artists' contributions to the movement's early expansion.[28] In 2015, "Stuckism: Remodernising the Mainstream" at Studio 3 Gallery in Kent presented over 70 paintings by 42 artists, reviving local interest since the movement's Medway origins.[30] Prominent artworks from UK Stuckists often critique cultural figures and consumerism, such as Charles Thomson's A Single Woman in London Is Never more than Six Inches from the Nearest Rat, a 1999 painting satirizing urban isolation through figurative narrative.[29] Eamon Everall's The Marriage (2002) depicts domestic scenes with symbolic depth, aligning with Stuckism's advocacy for personal authenticity over abstraction.[29] These pieces, frequently exhibited in the aforementioned shows, underscore the movement's commitment to painting as a medium of direct expression.[6]International Spread

Formation of Global Groups

The formation of Stuckist groups beyond the United Kingdom began in late 2000, driven by international interest sparked through the movement's website, which facilitated direct contact and endorsements from co-founder Charles Thomson.[1][31] The inaugural non-UK group, the Melbourne Stuckists, was established in October 2000 by artist Regan Tamanui in Australia, marking the fourth overall Stuckist entity and the first overseas expansion; this group promptly organized a "Real Turner Prize Show" in parallel with the London event, underscoring early alignment with core anti-establishment protests.[32][18] Subsequent groups emerged rapidly as independent entities allied via the Stuckism International network, with founders typically initiating after online engagement and Thomson's approval, though each operated autonomously without centralized control.[1] By 2002, the Munich Stuckists formed in Germany under Frank Schroeder, while U.S. chapters, including early activities documented in New York and New Haven, gained traction around 2001, evidenced by group demonstrations and gallery openings that echoed UK tactics against conceptual art dominance.[18] Canada's Vancouver Stuckists followed in 2003, led by Derek von Essen, contributing to a pattern of grassroots establishment in response to local art scenes perceived as elitist.[18] This decentralized model, leveraging digital communication as the first major art movement to do so systematically, enabled proliferation without formal hierarchy, resulting in over 170 groups across 41 countries by the mid-2000s and eventual growth to more than 200 in over 50 nations.[1][18] Early international formations emphasized shared principles of figurative painting and institutional critique, often manifesting in localized exhibitions and protests tailored to regional contexts, such as challenges to national contemporary art prizes.[31]Regional Variations and Key Examples

Stuckism's international branches maintain the movement's foundational opposition to conceptual art and emphasis on authentic figurative painting, but regional groups often incorporate local cultural motifs, media, and critiques of domestic art establishments. As an independent "non-movement," variations arise from autonomous group initiatives rather than centralized directives, leading to adaptations such as the integration of indigenous techniques or responses to regional institutional biases. By 2023, over 200 groups existed across more than 50 countries, with concentrations in North America, Europe, and Oceania demonstrating tailored expressions of Stuckist principles.[18] In North America, the United States hosts the largest number of Stuckist groups, exceeding 40, with early formations including the Pittsburgh Stuckists in 2000 led by Susan Constanse and the New York Stuckists in 2001 under Terry Marks. These groups mirrored UK activities through demonstrations against conceptual art dominance, such as protests at major institutions, while focusing on urban American themes in paintings critiquing consumer culture and media influence. Canadian branches, numbering six, emerged later, with Vancouver Stuckists founded in 2003 by Derek von Essen emphasizing community-based exhibitions that highlighted regional landscapes and anti-elitist narratives.[18] European variations outside the UK feature robust presences in France and Germany. The Paris Stuckists, established in 2001 by Elsa Dax, produced works blending mythological themes with critiques of French contemporary art scenes, exemplified by Dax's Bacchus series exploring personal authenticity amid institutional abstraction. Germany's Munich Stuckists, formed in 2002 by Frank Schroeder, and Berlin group in 2008, hosted exhibitions at centers like Atelier Lewenhagen, adapting Stuckism to confront post-war German art orthodoxy through expressive figuration influenced by Expressionism.[18][32] In Oceania, Australia marked the first international expansion with the Melbourne Stuckists in 2000, initiated by Regan Zero (also known as Regan Tamanui), which incorporated unique media like stonecarving in the Newcastle group established in 2001 to evoke indigenous and colonial histories. Sydney Stuckists, from 2008, extended this by organizing local protests against biennales favoring installation art. Asian examples include China's Beijing Stuckists, founded in 2001 by Richard Todd, which navigated censorship by focusing on introspective portraiture challenging state-sanctioned modernism, while Japan's Tokyo group from 2003 emphasized meticulous traditional techniques in anti-commercial statements.[18]Membership Dynamics

Prominent Members and Contributions

Billy Childish and Charles Thomson co-founded Stuckism on August 4, 1999, with eleven other artists, establishing the initial group of thirteen members in London.[1] [2] Childish, a prolific painter, musician, and poet, inspired the movement's name from an insult by his former partner, Tracey Emin, who derided his commitment to traditional painting as being "stuck."[2] He co-authored the foundational "Stuckist Manifesto," which advocated for authentic, holistic figurative art over conceptualism and institutional elitism, emphasizing uncensored personal expression and the rejection of artifice.[2] Childish departed the group in 2001 to pursue independent projects but continued producing works aligned with Stuckist principles, including paintings and prints drawing from personal experience.[1] Charles Thomson, an artist and lecturer, served as the movement's enduring leader after Childish's exit, organizing protests, exhibitions, and international expansion.[1] He co-authored the 1999 manifesto and later texts like "Remodernism," promoting spiritual renewal in art through direct engagement with reality rather than irony or detachment.[1] Thomson's contributions included spearheading annual demonstrations against the Turner Prize, such as clown-costumed protests outside Tate Britain starting in 2000, and curating shows like "The Real Turner Prize Show" in 2000 to showcase alternative figurative works.[1] His paintings, often narrative and satirical, critiqued consumer culture and art world hypocrisies, as seen in pieces addressing urban alienation.[1] Among other prominent members, Ella Guru developed the official Stuckism website in the early 2000s, enabling global networking and documentation of member activities across emerging groups.[1] Joe Machine, an autodidact and former prisoner, gained recognition for raw, confessional oil paintings depicting his life experiences, such as domestic scenes and celebrity portraits like Diana Dors with an Axe, which embodied Stuckism's valorization of outsider authenticity over polished technique.[1] Paul Harvey contributed detailed realist canvases integrating everyday objects and landscapes, exemplified by Ford Anglia with Tent and Giotto Tree, blending personal narrative with references to art history to affirm painting's vitality.[1] Eamon Everall and Philip Absolon furthered the movement through figurative works—Everall's The Marriage exploring domestic themes, and Absolon's Breakdown conveying emotional introspection—both reinforcing anti-elitist stances via accessible, emotive styles.[1] These artists collectively advanced Stuckism by participating in over 200 exhibitions by 2004, prioritizing self-taught vigor and thematic depth.[1]Ex-Stuckists and Internal Schisms

Co-founder Billy Childish departed Stuckism in 2001, shortly after its formal establishment, while affirming ongoing commitment to its emphasis on authentic, figurative painting over conceptualism.[4] [33] His reasons centered on a desire for solitary practice, eschewing organized group dynamics that might foster conformity or "echo chambers."[34] Several other artists have since exited the movement, often to pursue independent careers. Stella Vine, who joined in 2001 and featured in early exhibitions, later rejected affiliation, transitioning from proponent to critic of the group.[6] [35] Peter McArdle, who formed the Gateshead Stuckists subgroup in 2003, withdrew in 2008 amid his ongoing solo exhibitions and gallery work.[36] [37] The Stuckism website categorizes additional ex-members, including Gina Bold, Dave Beesley, Angela Edwards, Dan Belton, and Charles Williams, without detailing specific motives beyond personal divergence.[29] These departures reflect individual preferences for autonomy rather than broader ideological rifts, as no documented factional schisms or collective disputes have fractured the movement's core under Charles Thomson's leadership.[6]Reception, Critiques, and Controversies

Achievements and Positive Impacts

Stuckism secured institutional validation through the 2004 exhibition The Stuckists Punk Victorian at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, part of the Liverpool Biennial, marking the first national museum presentation of Stuckist works and featuring over 200 paintings by 41 artists that emphasized raw, expressive figurative styles.[32] This event drew significant attendance and media coverage, demonstrating the movement's capacity to engage public interest beyond fringe circles.[38] The exhibition highlighted Stuckism's advocacy for painting as a direct medium for personal and emotional truth, contrasting with prevailing conceptual trends.[6] The movement expanded globally, forming over 236 independent groups across 52 countries by 2018, fostering a decentralized network that sustained activity through self-organized shows and publications like the foundational Stuckist Manifesto of 1999, which articulated principles of holistic art integrating conscious and unconscious elements.[39] [2] This growth enabled the inclusion of outsider and naive artists, such as Joe Machine, whose prison-originated works gained visibility, promoting art as an accessible pursuit unhindered by formal training or elite gatekeeping.[40] Stuckism's emphasis on authentic figurative painting contributed to a broader revival of painterly practices in the early 21st century, influencing remodernist tendencies that prioritized individual expression over institutional approval and redefining artistic success as consistent creation rather than commercial acclaim.[41] By challenging the dominance of conceptual art, it sparked discourse on art's intrinsic value, encouraging practitioners to prioritize emotional content and technical engagement with traditional media, thereby democratizing participation in visual culture.[1]Criticisms from Art Establishment and Peers

The art establishment has predominantly dismissed Stuckism as a reactionary backlash against conceptual art, portraying its emphasis on figurative painting as nostalgic and resistant to innovation. Critics have argued that the movement's vehement opposition to trends like those promoted by Charles Saatchi and the Young British Artists (YBAs) positions it as traditionalist rather than forward-looking, with artists speaking out against the "brave new art establishment" routinely labeled as such.[6] This view frames Stuckism's promotion of paint as an "antiquated" medium, ignoring its claims to remodernism in favor of seeing it as a retreat from conceptualism's intellectual rigor.[42] Prominent art critic Jonathan Jones, writing in The Guardian on October 2, 2009, described Stuckism as "enemies of art," contending that its "cheap slogans and hysterical rants" do not advance figurative painting but instead "make it harder for creativity to thrive" by fostering divisive polemics over substantive dialogue.[43] Jones's critique highlights a broader establishment sentiment that Stuckist manifestos and protests—such as annual demonstrations outside Tate Britain during Turner Prize announcements—prioritize confrontation over artistic production, often reducing the movement to performative spectacle rather than a viable alternative.[44] Peers and institutional figures have largely ignored or marginalized Stuckism, with minimal engagement from YBA luminaries like Damien Hirst or gallery directors such as Tate's Nicholas Serota, contributing to its exclusion from major exhibitions and acquisitions. Charles Thomson, a co-founder, noted in a 2002 interview that the movement was "completely ignored by the art critics of the mainstream press," attributing this to a self-serving commercial art world intolerant of challenges to its dominance.[45] This neglect extended to a perception that Stuckism exists reactively, defined by opposition to conceptualism rather than independent merit, as articulated in analyses viewing it as "secondary" to the very BritArt it critiques.[46] Some commentators have criticized Stuckism for potentially stifling broader creativity by rigidly rejecting conceptual elements, labeling it at its extremes as a "moribund troupe of alternative painters lamenting dead art movements" instead of fostering inclusive evolution.[47] This perspective underscores concerns that its anti-elitist stance, while aimed at democratizing art, risks entrenching a narrow focus on technical skill over diverse expression, further alienating it from peers who see value in hybrid forms.[48]Debates on Innovation vs. Reactionism

Critics of Stuckism, particularly within the contemporary art establishment, have characterized the movement as reactionary, arguing that its emphasis on figurative painting and rejection of conceptualism constitutes a regressive backlash against modernist and postmodernist innovations. For instance, defenders of the Turner Prize have dismissed Stuckists as "absurdly reactionary" for failing to appreciate the Prize's role in advancing experimental forms, implying that Stuckism clings to outdated mediums like oil on canvas rather than embracing novelty-driven progress.[49] This view posits that Stuckism's manifestos, which prioritize emotional authenticity over formal experimentation, mimic 19th-century academic art without contributing fresh paradigms, thereby reinforcing a conservative cultural stasis amid the dominance of installation and performance since the 1990s.[50] Stuckist proponents counter that the movement is not a mere reaction but a forward-looking remodernism that innovates by reclaiming art's spiritual and communicative essence, which they contend has been eroded by postmodernism's ironic detachment and institutional commodification. The 2000 Remodernist Manifesto outlines this as a "rebirth of spiritual art," reapplying early modernism's visionary principles—such as personal insight over formalism—while rejecting the nihilism and elitism of late-20th-century trends, including CIA-backed abstract expressionism's suppression of figurative content since the 1950s.[51][52] Advocates like Charles Thomson emphasize inclusivity and self-knowledge through art processes, positioning Stuckism as a radical alternative that fosters human connection and profundity, rather than gimmickry, and anticipates painting's revival as evidenced by shifts in exhibitions like the 2005 Turner Prize nominees.[53] The tension underscores broader art-world divides: where establishment critiques often equate innovation with disruption of tradition—favoring conceptual works' shock value—Stuckism substantiates its case through sustained output, with over 200 international groups by the mid-2000s demonstrating adaptive, non-hierarchical growth beyond mere opposition.[54] Yet, even sympathetic analyses note that Stuckism's stylistic diversity, while avoiding uniformity, risks diluting revolutionary impact by echoing resolved historical debates on figuration versus abstraction, without uniquely transcending them.[55] This debate persists, with Remodernism's emphasis on perennial meaning challenging the presumption that reactionism equates to obsolescence, provided it yields verifiable cultural renewal.[52]Legacy and Ongoing Influence

Relation to Broader Art Movements

Stuckism arose as a vehement reaction against the dominance of conceptual art in the late 20th century, particularly the ironic, media-driven works of the Young British Artists (YBAs) and the institutional endorsement of non-figurative forms like installation, performance, and video art. Founded in 1999 by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson, the movement's inaugural manifesto condemned these trends for prioritizing shock value and commercialism over substantive ideas or authentic expression, positioning Stuckism as an advocate for painting as a direct, idea-infused medium capable of conveying personal truth.[2] This opposition extended to broader postmodern practices, which Stuckists viewed as fostering detachment and nihilism rather than meaningful communication.[1] Integral to Stuckism is its alignment with Remodernism, articulated in the March 1, 2000, manifesto co-authored by Childish and Thomson, which reframes the movement as a renewal of early Modernism's spiritual and visionary core—emphasizing integrity, self-knowledge, and transcendence over formalism or irony.[51] Remodernism critiques Postmodernism for disintegrating Modernism's potential without offering viable alternatives, instead proposing a "spiritual renaissance" that integrates body and soul through art's communicative power.[51] While inclusive of diverse disciplines, it reinforces Stuckism's focus on painting as a shamanistic tool for confronting the self and the divine, distinguishing it from Modernism's unfulfilled promises and Postmodernism's perceived futility.[1] Stuckism echoes elements of earlier figurative movements, such as Expressionism's raw emotionalism and Realism's commitment to observable truth, without seeking mere stylistic emulation; co-founder Childish, for instance, drew personal inspiration from Expressionists like Van Gogh and Impressionists, applying their immediacy to autobiographical narratives.[56] The Stuckist manifesto explicitly champions "realism over abstraction" and "content over void," adapting these historical impulses to critique contemporary elitism and promote unpretentious, process-driven creation.[2] This synthesis positions Stuckism not as isolationist but as a bridge to traditions valuing human-centered depiction, countering the abstraction and conceptual voids of 20th-century avant-gardes.[1]Current Status and Future Prospects

As of 2025, Stuckism endures as a decentralized, anti-establishment art network with 236 affiliated groups spanning 52 countries, emphasizing figurative painting and personal authenticity over conceptual trends.[14] The movement maintains visibility through online platforms, including an active Facebook group where members share recent works, such as Ella Guru's 2024 oil painting Mistress of Industry Slave of War.[57] Individual Stuckists continue sporadic exhibitions, exemplified by Joe Machine's 2021 show at Masterpiece Fine Art Gallery in Dubai, which highlighted outsider perspectives within the movement.[14] A notable 2025 development is the documentary Saving Stuckism: A to Zed, directed by American painter Ron Throop, which premiered internationally on September 20 at SUNY Oswego's Marano Campus Center Auditorium.[58] The film documents Throop's April 2025 trip to Muswell Hill, North London, to collaborate with British Stuckists, underscoring ongoing transatlantic ties and the movement's commitment to hands-on artistic practice amid institutional marginalization.[59] Charles Thomson, a co-founder, remains engaged, authoring a 2024 analysis of cultural iconography in CounterPunch that aligns with Stuckist critiques of superficial modernity.[60] Prospects for Stuckism hinge on its niche appeal to artists disillusioned with conceptual art dominance, potentially bolstered by digital dissemination and backlash against elite art markets. The 2025 documentary serves as a archival and promotional tool, suggesting sustained documentation efforts, though the movement's official site shows limited updates, indicating reliance on grassroots and individual initiatives rather than centralized growth.[61] Without penetration into major galleries or academia, Stuckism is likely to persist as a contrarian fringe, fostering small-scale home shows and online advocacy as it marks over 25 years since inception.[62]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stuckists_Saatchi_Gallery_leaflet_2005.jpg