Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sistan and Baluchestan province

View on Wikipedia

Sistan and Baluchestan province (Persian: استان سيستان و بلوچستان)[a] is the second largest of the 31 Provinces of Iran, after Kerman province, with an area of 180,726 km2. Its capital is the city of Zahedan.[4] The province is in the southeast of the country, bordering Afghanistan and Pakistan.[5][6]

Key Information

The name of the region was Baluchistan at first. Later it became «Baluchistan and Sistan», and today it has become «Sistan and Baluchestan».[7][8][9]

History

[edit]In the inscriptions at Behistun and Persepolis, Sistan is mentioned as one of the eastern territories of Darius the Great. The name Sistan is derived from Saka (also sometimes Saga, or Sagastan), a Central Asian tribe that had taken control over this area in the year 128 BC. During the Arsacid dynasty (248 BC to 224 AD), the province became the seat of Suren-Pahlav Clan. From the Sassanid period until the early Islamic period, Sistan flourished considerably.[citation needed]

During the reign of Ardashir I of Persia, Sistan came under the jurisdiction of the Sassanids, and in 644 AD, the Arab Muslims gained control as the Persian empire was in its final moments of collapsing. During the reign of the second Sunni caliph, Omar ibn Al-Khattab, this territory was conquered by the Arabs and an Arab commander was assigned as governor. The famous Persian ruler Ya'qub-i Laith Saffari, whose descendants dominated this area for many centuries, later became governor of this province. In 916 AD, Baluchestan was ruled by the Daylamids and thereafter the Seljuqids, when it became a part of Kerman. Dynasties such as the Saffarids, Samanids, Qaznavids, and Seljuqids, also ruled over this territory.[citation needed]

In 1508 AD, Shah Ismail I of the Safavid dynasty conquered Sistan. After the assassination of Nader Shah in 1747, Sistan and Balochistan became part of the Brahui Khanate of Kalat, which ruled it until 1896. Afterwards, it became part of Qajar Iran.[10]

Demographics

[edit]Ethnic demographics

[edit]The Baloch form a majority 70-76% of the population and the Persian Sistani a minority. Smaller communities of Kurds (in the eastern highlands and near Iranshahr); the expatriate Brahui (along the border with Pakistan); and other resident and itinerant ethnic groups, such as the Romani, are also found within the province.[citation needed]

Most of the population are Balōch and speak the Baluchi language, although there also exists among them a small community of speakers of the Indo-Aryan language Jadgali.[11]: 25 Baluchestan means "Land of the Balōch"; Sistani Persians are the second largest ethnic group in this province who speak the Sistani dialect of Persian.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]

The majority of the Baloch people of the Baluchestan area in the province are Sunni Muslims, belonging to Hanafi school of thought.[12][13][14]

Population

[edit]At the time of the 2006 National Census, the province's population was 2,349,049 in 468,025 households.[15] The following census in 2011 counted 2,534,327 inhabitants living in 587,921 households.[16] The 2016 census measured the population of the province as 2,775,014 in 704,888 households.[2]

Administrative divisions

[edit]The population history and structural changes of Sistan and Baluchestan Province's administrative divisions over three consecutive censuses are shown in the following table.

| Counties | 2006[15] | 2011[16] | 2016[2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bampur[b] | — | — | — |

| Chabahar | 214,017 | 264,051 | 283,204 |

| Dalgan[c] | — | 62,813 | 67,857 |

| Dashtiari[d] | — | — | — |

| Fanuj[e] | — | — | 49,161 |

| Golshan[f] | — | — | — |

| Hamun[g] | — | — | 41,017 |

| Hirmand[h] | — | 65,471 | 63,979 |

| Iranshahr | 264,226 | 219,796 | 254,314 |

| Khash | 161,918 | 155,652 | 173,821 |

| Konarak | 68,605 | 82,001 | 98,212 |

| Lashar[i] | — | — | — |

| Mehrestan[j] | — | 62,756 | 70,579 |

| Mirjaveh[k] | — | — | 45,357 |

| Nik Shahr | 185,355 | 212,963 | 141,894 |

| Nimruz[g] | — | — | 48,471 |

| Qasr-e Qand[l] | — | — | 61,076 |

| Rask[m] | — | — | — |

| Saravan | 239,950 | 175,728 | 191,661 |

| Sarbaz | 162,960 | 164,557 | 186,165 |

| Sib and Suran[n] | — | 73,189 | 85,095 |

| Taftan[o] | — | — | — |

| Zabol | 317,357 | 259,356 | 165,666 |

| Zahedan | 663,822 | 660,575 | 672,589 |

| Zarabad[p] | — | — | — |

| Zehak | 70,839 | 75,419 | 74,896 |

| Total | 2,349,049 | 2,534,327 | 2,775,014 |

Cities

[edit]According to the 2016 census, 1,345,642 people (over 48% of the population of Sistan and Baluchestan province) live in the following cities:[2]

| City | Population |

|---|---|

| Adimi | 3,613 |

| Ali Akbar | 4,779 |

| Bampur | 12,217 |

| Bazman | 5,192 |

| Bent | 5,822 |

| Bonjar | 3,760 |

| Chabahar | 106,739 |

| Dust Mohammad | 6,621 |

| Espakeh | 4,719 |

| Fanuj | 13,070 |

| Galmurti | 10,292 |

| Gosht | 4,992 |

| Hiduj | 1,674 |

| Iranshahr | 113,750 |

| Jaleq | 18,098 |

| Khash | 56,584 |

| Konarak | 43,258 |

| Mehrestan | 12,245 |

| Mirjaveh | 9,359 |

| Mohammadabad | 3,468 |

| Mohammadan | 10,302 |

| Mohammadi | 5,606 |

| Negur | 5,670 |

| Nik Shahr | 17,732 |

| Nosratabad | 5,238 |

| Nukabad | 5,261 |

| Pishin | 16,011 |

| Qasr-e Qand | 11,605 |

| Rask | 10,115 |

| Saravan | 60,014 |

| Sarbaz | 2,020 |

| Sirkan | 2,196 |

| Suran | 13,580 |

| Zabol | 134,950 |

| Zahedan | 587,730 |

| Zarabad | 4,003 |

| Zehak | 13,357 |

The following table shows the ten largest cities of Sistan and Baluchestan province:[2]

| Rank | Name | Population (2016) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zahedan | 587,730 |

| 2 | Zabol | 134,950 |

| 3 | Iranshahr | 113,750 |

| 4 | Chabahar | 106,739 |

| 5 | Saravan | 60,014 |

| 6 | Khash | 56,584 |

| 7 | Konarak | 43,258 |

| 8 | Jaleq | 18,098 |

| 9 | Nik Shahr | 17,732 |

| 10 | Pishin | 16,011 |

Geography

[edit]The whole of the province had previously been called Baluchestan, but the government added Sistan to the end of Baluchestan and became Baluchestan and Sistan. After the 1979 revolution, the name of the province was changed to Sistan and Baluchestan.[7][8]

Today, Sistan refers to the area comrising Zabol, Hamun, Hirmand, Zehak and Nimruz counties.[30] The province borders South Khorasan Province in the north, Kerman Province and Hormozgan Province in the west, the Gulf of Oman in the south, and Afghanistan and Pakistan in the east.

Sistan and Baluchestan Province is one of the driest regions of Iran, with a slight increase in rainfall from east to west, and a rise in humidity in the coastal regions. The province is subject to seasonal winds from different directions, the most important of which are the 120-day wind of Sistan, known in Baluchi as Levar; the seventh wind (Gav-kosh); the south wind (Nambi); the Hooshak wind; the humid and seasonal winds of the Indian Ocean; the north wind (Gurich); and the western wind (Gard).

In 2023, Sistan region was affected by several dust events, occurring in April,[31] June,[30] and August. The latter sent 1120 people to hospitals from 10 to 14 August. Winds reached a speed of 108 km/h (67 mph) in Zabol station and reduced visibility to 600 m (2,000 ft).[32]

Sistan and Baluchestan today

[edit]

Sistan and Baluchestan is the poorest of Iran's 31 provinces, with a HDI score of 0.688.[3]

The government of Iran has been implementing new plans such as creating the Chabahar Free Trade-Industrial Zone.

Economy

[edit]

Industry is new to the province. Efforts have been done and tax, customs and financial motivations have caused more industrial investment, new projects, new producing jobs and improvement of industry. The most important factories are the Khash cement factory with production of 2600 tons cement daily and three other cement.

Factories under construction:

- Cotton cloth and fishing net weaving factories and the brick factory can be named as well.

The province has important geological and metal mineral potentials such as chrome, copper, granite, antimony, talc, manganese, iron, lead, zinc, tin, nickel, platinum, gold and silver.

One of the main mines in this province is Chel Kooreh copper mine in 120 km north of Zahedan.

Sistan embroidery has been an ancient handicraft of the region that has been traced as far back as 5th-century BC, originating from the Scythians.[33]

Transportation

[edit]Road transport

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) |

National rail network

[edit]The city of Zahedan has been connected to Quetta in Pakistan for a century with a broad gauge railway. It has weekly trains for Kovaitah. Recently a railway from Bam, Iran to Zahedan has been inaugurated. There may be plans to build railway lines from Zahedan to Chabahar.[34]

Airports

[edit]

Sistan and Baluchistan province has two main passenger airports:

- Zahedan Airport

- Chabahar Airport (Konarak Airport)

Ports

[edit]The Port of Chabahar in the south of the province is the main port. It is to be connected by a new railway to Zahedan. India is investing on this port. The port stands on the Coast of Makran and is 70 km west of Gwadar, Pakistan.[35]

Higher education

[edit]- University of Sistan and Baluchestan

- Chabahar Maritime University

- Zabol University

- Islamic Azad University of Iranshahr

- Islamic Azad University of Zahedan[36]

- Zahedan University of Medical Sciences[37]

- Zabol University of Medical Sciences

- International University of Chabahar

- Velayat University of Iranshar

- Jamiah Darul Uloom Zahedan

Water

[edit]Iran ranks among the most water stressed countries in the world. Sistan-Baluchestan province suffers from major water problems that were aggravated by corruption in Iran's water supply sector, lack of transparency, neglect of marginalized communities, and political favoritism. The IRGC and other politically connected entities control water resources, prioritizing projects for political and economic gain rather than public need. They divert supplies to favored regions, causing shortages in vulnerable provinces like Khuzestan and Sistan-Baluchestan. For example, water diversion projects in Isfahan and Yazd provinces receive priority despite critical shortages in Khuzestan and Sistan-Baluchestan. Reports also indicate that certain agricultural and industrial enterprises with ties to the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) have received significant amounts of water, while small farmers and rural communities struggle with severe shortages.[38]

Iran's central government prioritizes water allocation for industrial and urban centers, often at the expense of rural and minority populations. These groups face severe water shortages, ecological degradation, and a loss of livelihoods. This pattern of unequal development not only exacerbates regional disparities but also fuels social unrest and environmental crises. Iran's water policy is also characterized by an overreliance on dam construction and large-scale diversion projects, primarily benefiting politically connected enterprises and urban elites. This has led to the drying of rivers, wetlands, and other vital ecosystems, intensifying dust storms and land subsidence in regions like Khuzestan and Sistan-Baluchestan. Such environmental degradation, combined with insufficient governmental oversight and transparency, worsens living conditions for marginalized communities, reinforcing cycles of poverty and socio-political marginalization.[39]

Gallery

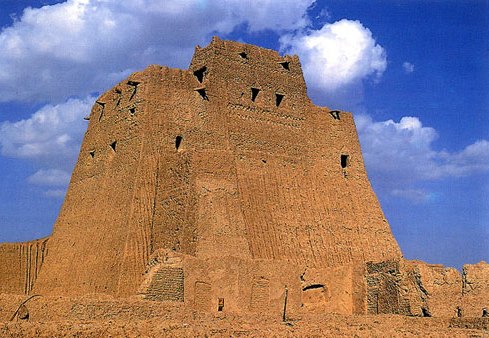

[edit]Landmarks such as the Firuzabad Castle, Rostam Castle and the Naseri Castle are located in the province.

-

Naseri Castle, Iranshahr

See also

[edit]- Balochi cuisine

- Bazman, volcano mountain

- Baloch people

- Sistan region

- Balochistan region

- Balochistan, Afghanistan

- Balochistan, Pakistan

![]() Media related to Sistan and Baluchestan Province at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sistan and Baluchestan Province at Wikimedia Commons

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also romanized as Ostân-e Sistân o Balučestân

- ^ Separated from Iranshahr County after the 2016 census[17]

- ^ Separated from Iranshahr County after the 2006 census[18]

- ^ Separated from Chabahar County after the 2016 census[19]

- ^ Separated from Nik Shahr County after the 2011 census

- ^ Separated from Saravan County after the 2016 census[20]

- ^ a b Separated from Zabol County after the 2011 census[21]

- ^ Separated from Zabol County after the 2006 census[22]

- ^ Separated from Nik Shahr County after the 2016 census[23]

- ^ Separated from Saravan County and Sarbaz County after the 2006 census[24]

- ^ Separated from Zahedan County after the 2011 census[25]

- ^ Separated from Chabahar County and Nik Shahr County after the 2011 census[26]

- ^ Separated from Sarbaz County after the 2016 census[27]

- ^ Separated from Saravan County after the 2006 census[24]

- ^ Separated from Khash County after the 2016 census[28]

- ^ Separated from Konarak County after the 2016 census[29]

References

[edit]- ^ OpenStreetMap contributors (8 January 2025). "Sistan and Baluchestan Province" (Map). OpenStreetMap (in Persian). Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1395 (2016): Sistan and Baluchestan Province. amar.org.ir (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Habibi, Hassan (5 March 2013) [Approved 21 June 1369]. Approval of the organization and chain of citizenship of the elements and units of the national divisions of Sistan and Baluchestan province, centered in the city of Zahedan. rc.majlis.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Defense Political Commission of the Government Board. Proposal 3233.1.5.53; Letter 907-93808; Notification 82822/T129. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2023 – via Research Center of the System of Laws of the Islamic Council of the Farabi Library of Mobile Users.

- ^ "معرفی استان سیستان و بلوچستان". hprc.zaums.ac.ir. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "آشنایی با استان سیستان و بلوچستان". hamshahrionline.ir. 25 May 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Inside Iran's Most Secretive Region". The Diplomat. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

Eighty years ago, this area was called "Balochistan." Later it became "Balochistan and Sistan" and today it's "Sistan and Balochistan"

- ^ a b "Sistan and Baluchestan Tourist and Travel Guide". ADVENTURE IRAN. Retrieved 26 January 2025.

Sistan and Baluchestan province comprises two large sections, Sistan in the north and Baluchestan in the south. The Farsi name "Sistan" comes from Old Persian Sakastana, meaning "Land of the Saka". The name Baluchestan- also written "Baluchestan"- means "Land of the Baluch" in the Persian language and is used to represent the majority of Baloch people inhabiting the province. Sistan was added to thLarge intestinee name of the Baluchestan province to represent the minority Persian people who speak the Sistani dialect of Persian.

- ^ Sajidi, Jiand (20 October 2022). "Western Balochistan: Past and Present". The Baloch News. Retrieved 3 October 2025.

- ^ "Brahui". Encyclopedia Irannica.

- ^ Delforooz, Behrooz Barjasteh (2008). "A sociolinguistic survey of among the Jagdal in Iranian Balochistan". In Jahani, Carina; Korn, Agnes; Titus, Paul Brian (eds.). The Baloch and others: linguistic, historical and socio-political perspectives on pluralism in Balochistan. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag. pp. 23–44. ISBN 978-3-89500-591-6.

- ^ Sistan and Baluchestan Province tabnak.ir. Retrieved 20 July 2020

- ^ "Ahmady, Kameel. A Peace-Oriented Investigation of the Ethnic Identity Challenge in Iran (A Study of Five Iranian Ethnic Groups with the GT Method), 2022, 13th Eurasian Conferences on Language and Social Sciences pp.591-624". 13th Eurasian Conferences on Language and Social Sciences. 2022. Pp.591-624.

- ^ "Baluchistan | History, People, Religion, & Map | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ a b Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1385 (2006): Sistan and Baluchestan Province. amar.org.ir (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ a b Census of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1390 (2011): Sistan and Baluchestan Province. irandataportal.syr.edu (Report) (in Persian). The Statistical Center of Iran. Archived from the original (Excel) on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022 – via Iran Data Portal, Syracuse University.

- ^ Jahangiri, Ishaq (c. 2023) [Approved 13 August 1397]. Letter of approval regarding reforms and divisional changes in Sistan and Baluchestan province. qavanin.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Council of Ministers. Proposal 163101. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023 – via Laws and Regulations Portal of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ^ Davodi, Parviz (c. 2013) [Approved 18 September 1386]. Approval letter regarding the reforms of national divisions in Sistan and Baluchestan province, Iranshahr County. rc.majlis.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior. Proposal 93023/42/4/1; Letter 58538/T26118H; Notification 161466/T38028K. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2023 – via Research Center of the Islamic Council.

- ^ Jahangiri, Ishaq (c. 2023) [Approved 13 September 1398]. Letter of approval regarding the national divisions of Chabahar County, Sistan and Baluchestan province. qavanin.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Council of Ministers. Proposal 20047. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2023 – via Laws and Regulations Portal of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ^ Jahangiri, Ishaq (21 December 2019) [Approved 17 October 1399]. "Approval letter regarding some national divisions in Saravan County of Sistan and Baluchestan province". dotic.ir (in Persian). Ministry of Interior, Board of Ministers. Proposal 193481. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2023 – via Laws and Regulations Portal of Iran.

- ^ Rahimi, Mohammad Reza (c. 2023) [Approved 29 September 1391]. "Carrying out national divisions about Saberi and Teymurabad and Nimruz and Hamun Counties of Sistan and Baluchestan province". qavanin.ir (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Council of Ministers. Proposal 174107/42/4/1. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023 – via Laws and Regulations Portal of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ^ Davodi, Parviz (c. 2023) [Approved 5 March 1386]. "Reforms of national divisions in Sistan and Baluchestan province, Zabol County". qavanin.ir (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Board of Ministers. Proposal 4/1/42/149078; Letter 58538/T26118AH. Archived from the original on 21 July 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2023 – via Laws and Regulations Portal of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ^ Jahangiri, Ishaq (c. 2022) [Approved 13 April 1400]. Letter of approval regarding national divisions in Fanuj and Nik Shahr Counties in Sistan and Baluchestan province. qavanin.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Council of Ministers. Proposal 160989. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2023 – via Laws and Regulations Portal of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ^ a b Davodi, Parviz (c. 2023) [Approved 29 July 1386]. The approval letter of the Ministers of the Political-Defense Commission of the Government Board regarding some changes and divisions of the country in Sistan and Baluchestan province. lamtakam.com (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Political-Defense Commission of the Government Board. Proposal 93023/42/1/4; Letter 58538/T26118H; Notification 161431/T38028K. Archived from the original on 30 December 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023 – via Lam ta Kam.

- ^ Rahimi, Mohammad Reza (21 October 2012) [Approved 29 September 1391]. Resolution on the national divisions in Sistan and Baluchestan province. rc.majlis.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Council of Ministers. Proposal 5676/42/4/1; Notification 200666/T46606H. Archived from the original on 10 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2025 – via Research Center of the Law System of the Islamic Consultative Assembly of the Farabi Library of Mobile Users.

- ^ Rahimi, Mohammad Reza (c. 2023) [Approved 29 September 1391]. Carrying out reforms of national divisions in Sistan and Baluchestan province. qavanin.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Council of Ministers. Proposal 5603/42/1/1. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2023 – via Laws and Regulations Portal of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ^ Jahangiri, Ishaq (c. 2023) [Approved 13 September 1398]. Letter of approval regarding the national divisions of Sarbaz County of Sistan and Baluchestan province. qavanin.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Council of Ministers. Proposal 235379. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023 – via Laws and Regulations Portal of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ^ Jahangiri, Ishaq (4 February 2018) [Approved 13 September 1398]. Approval letter regarding the national divisions of Khash County of Sistan and Baluchestan province. rc.majlis.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Council of Ministers. Proposal 84088; Notification 120508/T56818H. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2023 – via Islamic Parliament Research Center of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- ^ Jahangiri, Ishaq (12 September 2021) [Approved 13 April 1400]. Approval regarding the national divisions in the counties of Dashtiari, Chabahar and Konarak in Sistan and Baluchestan province. sdil.ac.ir (Report) (in Persian). Ministry of the Interior, Cabinet of Ministers. Proposal 160986; Notification 40833/T58355AH. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2025 – via Shahr Danesh Legal Research Institute.

- ^ a b "Storm in Sistan sent 330 people to medical centers" توفان در سیستان ۳۳۰ نفر را راهی مراکز درمانی کرد, Tabnak (in Persian), 25 June 2023, 1180454, retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "The storm sent 99 people to the hospital in Sistan region" توفان در منطقه سیستان ۹۹ نفر را راهی بیمارستان کرد, Tabnak (in Persian), 18 April 2023, 1171738, retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "1120 people went to hospital in Sistan and Baluchistan" ۱۱۲۰ نفر در سیستان و بلوچستان راهی بیمارستان شدند. tabnak.ir (in Persian). Tabnak. 14 August 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "هفتهزار سال هنر در یک سرزمین" [Seven thousand years of art in one land]. ایسنا (in Persian). 15 March 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Projects Invest Iran [dead link]

- ^ "From Gwadar to Chabahar, the Makran Coast Is Becoming an Arena for Rivalry Between Powers". The Wire.

- ^ "دانشگاه آزاد اسلامی واحد زاهدان". iauzah.ac.ir. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ "Zahedan University of Medical Sciences(zdmu)". 17 July 2007. Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Kuzma, Samantha; Saccoccia, Liz; Chertock, Marlena (16 August 2023). "25 Countries, Housing One-Quarter of the Population, Face Extremely High Water Stress".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Water, Corruption, and Security in Iran". New Security Beat. 23 January 2024. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- W. Barthold (1984). "Sistan, the Southern Part of Afghanistan, and Baluchistan". An Historical Geography of Iran. Translated by Svat Soucek. Princeton University Press. pp. 64–86. ISBN 978-1-4008-5322-9.

- Kameel Ahmady (2019). From border to border. Comprehensive research study on identity and ethnicity in Iran. London: Mehri publication. ISBN 9781914165221.

External links

[edit]Sistan and Baluchestan province

View on GrokipediaHistory

Pre-Islamic Period

The region encompassing modern Sistan and Baluchestan shows archaeological evidence of human occupation from the fourth millennium BCE, with sites in Baluchestan linked to early trade networks involving Mesopotamian civilizations such as Sumer and Akkad, where the area was referred to as Makan or Meluhha.[6] In the Sistan basin, Bronze Age settlements of the Helmand Civilization, dating to the third millennium BCE, demonstrate cultural and material exchanges with the Indus Valley Civilization, including shared pottery styles and settlement patterns. These early communities relied on irrigation agriculture in the fertile plains around Lake Hamun and the Helmand River, amidst a predominantly arid landscape. Under the Achaemenid Empire, the northern Sistan area formed the satrapy of Zranka (Greek Drangiana), conquered by Cyrus the Great circa 550 BCE and administratively organized by Darius I (r. 522–486 BCE) as a tax district inhabited by tribes such as the Sarangians.[7] The southern Baluchestan portion corresponded to the satrapy of Maka (Makran), integrated into the empire's eastern frontier provinces as attested in inscriptions at Bisotun and Persepolis.[6] The Achaemenid capital of Drangiana, Phrada (possibly near modern Dahan-i Ghulaman), served as an administrative center amid the region's wetlands and dunes. Alexander the Great subdued Drangiana in November 330 BCE during his campaign against Darius III, renaming the capital Prophthasia after thwarting a conspiracy there and appointing Arsames as satrap.[7] In 325 BCE, Alexander's return march from India traversed the Gedrosian desert encompassing southern Baluchestan, resulting in heavy casualties from thirst and terrain, with key settlements like Pura (possibly Bampur) noted as trade hubs.[6][7] Post-Alexander, the territory came under Seleucid control following Seleucus I Nicator's consolidation circa 312 BCE, before shifting to Parthian dominance in the second century BCE.[7] Around 128 BCE, invading Sakas (Scythians) established control over Sistan, renaming it Sakastan ("land of the Sakas"), a designation persisting into later eras.[7] The region, including fortified sites like Kuh-i Khwaja with its pre-Islamic temple complexes and palaces, remained a strategic eastern province under Parthian and subsequent Sasanian rule; during this era, Buddhism spread into Sistan via Bactria, Arachosia, and Kushan influence from the 1st century BCE to 1st century CE, with communities persisting despite Zoroastrian state dominance and occasional persecutions, as indicated by Chinese pilgrim accounts and studies of eastern Iranian Buddhism, until the mid-seventh century CE Arab invasions.[8][9][10]Islamic Era to Qajar Dynasty

The Arab conquest of Sistan occurred in 651 CE during the caliphate of ʿUthmān, when forces under ʿAbdallāh b. ʿĀmer entered the region from Khorasan, marking the initial Muslim incursion into this eastern frontier province of the former Sasanian Empire.[11] The area, previously known as Sakastān, came under Umayyad administration, with governors appointed from Basra; resistance persisted, including Zoroastrian revolts suppressed around 697 CE.[11] Under the Abbasids from 750 CE, Sistan functioned as a semi-autonomous border zone against Central Asian threats, fostering local military leaders amid caliphal weakening. In 861 CE, Yaʿqūb b. Layṯ al-Saffār, a native coppersmith (ṣaffār) from Sistan, overthrew Tahirid rule and established the Saffarid dynasty, nominally vassal to the Abbasids but effectively independent.[12] From Zaranj as capital, the Saffarids expanded aggressively, capturing Khorasan by 867 CE, Fars by 875 CE, and challenging Baghdad itself in 879 CE, before defeats limited their realm primarily to Sistan by the 10th century.[12] The dynasty endured until 1003 CE, promoting Persian cultural revival and Sunni orthodoxy against Shiʿa Buyids. Successors, the Nasrids (or Maliks of Nimruz, ca. 913–1220 CE), maintained localized control in Sistan as vassals to larger powers, resisting Ghaznavid incursions in the 11th century.[11] Subsequently, Sistan experienced successive overlordships: Ghaznavids exerted influence from ca. 1000 CE, followed by Seljuk conquest around 1041 CE, integrating it into their Turco-Persian empire until Mongol invasions devastated the region in 1221 CE.[11] Timurid rule from the late 14th century brought temporary stability, but post-Timurid fragmentation led to local autonomy under petty dynasties. Safavids incorporated Sistan by 1508 CE under Shāh Ismāʿīl I, enforcing Shiʿism amid resistance from Sunni populations.[11] Afsharid and Zand interregna (1736–1794 CE) saw intermittent control, often contested by Afghan incursions. In adjacent Baluchestan (encompassing Makrān and surrounding highlands), Arab forces under ʿUthmān conquered Makrān in 644 CE, but the arid terrain limited sustained governance, reverting to de facto tribal autonomy.[13] Baloch tribes, first documented in 9th-century Arabic sources as pastoralists in Kermān and Sistan, underwent eastward migrations from the 11th century amid Seljuk disruptions, establishing presence in the lowlands by the 13th–14th centuries.[13] The region evaded firm central control under Ghaznavids, Seljuks, and Mongols, with Buyid campaigns against Baloch raiders noted in 971–972 CE.[13] Under Safavids and Mughals, Baluchestan fragmented into confederacies, culminating in the Aḥmadzay Khanate of Kalāt founded in 1666 CE by Mīr Aḥmad Khan, who allied with Mughal India for expansion.[13] Naṣīr Khan I (r. ca. 1740s–1795 CE) unified much of the highlands, but Qajar consolidation from 1794 CE involved military expeditions, including Moḥammad Shāh's campaigns (1838–1844 CE) against rebellious chiefs like Āqā Khān.[13] During the Qajar era (1794–1925 CE), Sistan's settlements shifted due to Hirmand River channel alterations, prompting construction of fortified outposts for defense against nomads and water scarcity.[14] Baluchestan remained tribal, with Qajar governors overseeing ports like Chabahar but facing persistent insurgency, as in Sardār Ḥosayn Khān's revolt (1897–1900 CE) against central authority.[13] Anglo-Persian rivalries over the area intensified, yet Qajar suzerainty integrated it loosely into the empire's southeastern periphery.20th Century Integration and Conflicts

In the early 20th century, Sistan and Baluchestan, long characterized by Baloch tribal autonomy under loose Qajar oversight, underwent forceful integration into the centralized Iranian state under Reza Shah Pahlavi. Following his 1925 deposition of the Qajars, Reza Shah initiated military campaigns to disarm tribes and assert direct control. In 1928, General Amīr Amān-Allāh Jahānbānī commanded operations from August to December that defeated prominent tribal figures, including Dūst-Moḥammad Khan, culminating in the formal annexation of West Baluchistan as a province.[15][5] Centralization policies included suppressing local governance structures, resettling populations to weaken ethnic cohesion, and redrawing administrative boundaries to incorporate the region more firmly into national frameworks. Tribal resistance to these measures, rooted in opposition to disarmament and taxation, sparked several uprisings. The 1931 rebellion in Sarḥadd, led by Jomʿa Khan Esmāʿīlzay, sought to restore autonomy but was crushed, with the leader exiled to Shiraz. In 1938, Kūhak tribes revolted against new customs duties, resulting in 74 deaths during suppression by forces under General Alborz.[15] During Mohammad Reza Shah's reign (1941–1979), integration shifted toward co-optation, with economic incentives, land allocations to compliant elites, and infrastructure projects aimed at fostering loyalty and reducing separatism. However, underlying tensions persisted, as evidenced by the 1960s Free Baluchistan movement under Mīr ʿAbdī Khan Sardārzay, which demanded cultural and political recognition before being dismantled through exile and arrests.[15] The 1979 Islamic Revolution disrupted prior accommodations, exacerbating conflicts as the new regime prioritized ideological uniformity over ethnic pluralism, viewing the Sunni-majority Baloch areas as a perennial security risk. Separatist activities revived under figures like Amān-Allāh Bārakzay, evolving into low-intensity insurgency by the 1980s–1990s, fueled by grievances over marginalization, cross-border tribal ties with Pakistan and Afghanistan, and limited development.[15][5]Geography

Topography and Borders

Sistan and Baluchestan Province occupies southeastern Iran, sharing an approximately 959-kilometer border with Pakistan to the east and a combined land border of about 1,100 kilometers with Pakistan and Afghanistan to the northeast.[16][17] To the south, the province features a 300-kilometer coastline along the Gulf of Oman, part of the Makran Coast.[17] Internally, it adjoins South Khorasan Province to the north, Kerman Province to the northwest, and Hormozgan Province to the southwest.[1] The province's topography is diverse, encompassing arid plains, rugged mountains, and coastal lowlands, with an average elevation of 763 meters.[18] The northern Sistan region consists of a low-lying alluvial plain and the seasonal Hamun depression, fed intermittently by the Helmand River originating in Afghanistan.[19] Central and western areas rise into the Baluchestan Plateau and mountain ranges, including volcanic peaks like Taftan at 3,947 meters and Bazman at 3,503 meters.[20] In the south, the Makran zone features narrow coastal strips along the Gulf of Oman, backed by steep parallel mountain ranges such as the Central Makran Range, with seasonal rivers like the Bahu Kalat draining eastward.[21] The overall terrain contributes to the province's aridity, with vast desert expanses and limited perennial water sources beyond border-fed systems.[1]Climate and Natural Resources

Sistan and Baluchestan province exhibits a desert climate under the Köppen classification, marked by extreme aridity and minimal precipitation throughout most of the region. Annual rainfall averages below 100 millimeters in inland areas such as Zahedan, with virtually no measurable precipitation during extended dry periods.[22][23] Summer temperatures frequently surpass 40°C, peaking at around 42.6°C in July across the province, while winter lows dip to approximately 7.15°C in January.[24] The northern Sistan subregion faces intensified aridity due to the prolonged drying of Lake Hamun, exacerbated by upstream damming in Afghanistan and regional climate variability, resulting in recurrent dust storms and acute water shortages.[25] Southern Baluchestan, bordering the Gulf of Oman, benefits marginally from maritime influences, yielding slightly higher humidity and occasional monsoon-driven rains, though overall precipitation remains under 200 millimeters annually in coastal zones.[26] These conditions contribute to widespread drought vulnerability, with satellite data indicating persistent water stress and desertification trends as of 2024.[27] Natural resources are dominated by mineral deposits, positioning the province as a key mining area with reserves of 28 distinct mineral types, including chromite, copper, gold, antimony, and titanium.[28] Official assessments highlight untapped potential in these commodities, though extraction is limited by infrastructure deficits and security issues. The Makran coastline supports fisheries, leveraging the Gulf of Oman's rich marine ecosystem for sardines and other species, though overexploitation and environmental pressures constrain yields. Agriculture is severely limited by water scarcity, relying on irrigation for crops like dates and citrus in oases, with northern melon production historically viable but now diminished due to desiccation.[29]Demographics

Population Trends and Density

The population of Sistan and Baluchestan province stood at 2,534,327 according to the 2011 Iranian census, increasing to 2,775,014 by the 2016 census, yielding an average annual growth rate of about 1.8% over that period.[1][30] This rate exceeded the national average of roughly 1.3%, driven by the province's notably young demographic structure, with 37.6% of residents under age 15 in 2011 compared to lower proportions elsewhere in Iran.[31][32] Projections based on census trends estimate the population reached approximately 3.25 million by 2023, assuming sustained growth amid national fertility declines.[33] Urbanization remains limited, with roughly 48.5% of the 2016 population residing in urban areas, making it the only Iranian province where rural dwellers constitute a slim majority (about 51%).[5] This contrasts with the national urban share of over 70%, reflecting sparse infrastructure, economic marginalization, and reliance on pastoral and subsistence agriculture in rural districts.[32] Internal migration to urban centers like Zahedan has accelerated modestly, but net out-migration to more prosperous provinces persists due to high poverty rates—exceeding one-third in rural areas—and chronic underinvestment.[34] Spanning 180,726 square kilometers, the province exhibits one of Iran's lowest population densities at approximately 15.4 inhabitants per square kilometer in 2016, rising to an estimated 17.9 by 2023.[35][33] This sparsity stems from harsh arid topography, limited water resources, and security instability along borders with Pakistan and Afghanistan, which constrain settlement in vast desert and mountainous expanses.[1] Despite growth, density lags far behind the national figure of 46 per square kilometer, underscoring the province's peripheral status in Iran's demographic landscape.[32]| Census Year | Population | Annual Growth Rate (Prior Period) | Density (per km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2,534,327 | - | ~14.0 |

| 2016 | 2,775,014 | 1.8% (2011–2016) | ~15.4 |