Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chu (state)

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Chu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Chu" in seal script (top) and regular (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 楚 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chu (Chinese: 楚; pinyin: Chǔ; Wade–Giles: Ch'u,[2] Old Chinese: *s-r̥aʔ[3]) was an ancient Chinese state during the Zhou dynasty. Their first ruler was King Wu of Chu in the early 8th century BC. Chu was located in the south of the Zhou heartland and lasted during the Spring and Autumn period. At the end of the Warring States period it was annexed by the Qin in 223 BC during the Qin's wars of unification.

Also known as Jing (荊) and Jingchu (荊楚), Chu included most of the present-day provinces of Hubei and Hunan, along with parts of Chongqing, Guizhou, Henan, Anhui, Jiangxi, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai. For more than 400 years, the Chu capital Danyang was located at the junction of the Dan and Xi Rivers[4][5] near present-day Xichuan County, Henan, but later moved to Ying. The house of Chu originally bore the ancestral temple surname Nai (嬭 OC: /*rneːlʔ/) which was later written as Mi (芈 OC: /*meʔ/). They also bore the lineage name Yan (酓 OC: /*qlamʔ/, /*qʰɯːm/) which would later be written Xiong (熊 OC: /*ɢʷlɯm/).[6][7]

History

[edit]Founding

[edit]According to legends recounted in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, the ruling family of Chu descended from the Yellow Emperor and his grandson and successor Zhuanxu. Zhuanxu's great-grandson Wuhui (吳回) was put in charge of fire by Emperor Ku and given the title Zhurong. Wuhui's son Luzhong (陸終) had six sons, all born by Caesarian section. The youngest, Jilian, adopted the ancestral surname Mi.[8] Jilian's descendant Yuxiong was the teacher of King Wen of Zhou (r. 1099–1050 BC). After the Zhou overthrew the Shang dynasty, King Cheng (r. 1042–1021 BC) enfeoffed Yuxiong's great-grandson Xiong Yi with the fiefdom of Chu in the Nanyang Basin and the hereditary title of 子 (zǐ, "viscount"). Then the first capital of Chu was established at Danyang (present-day Xichuan in Henan).[8]

Sinologist Yuri Pines wrote that Chu originated as a normative Zhou polity that gradually developed cultural assertiveness in tandem with the increase in its political power, rather than being a "barbarian entity" drawn to the glory of the Zhou culture as suggested in the Mencius, and that divergent cultural patterns associated with Chu only emerged during the Spring and Autumn period.[9]

Western Zhou

[edit]In 977 BC, during his campaign against Chu, King Zhao of Zhou's boat sank and he drowned in the Han River. After this death, Zhou ceased to expand to the south, allowing the southern tribes and Chu to cement their own autonomy much earlier than the states to the north. The Chu viscount Xiong Qu overthrew E in 863 BC but subsequently made its capital Ezhou one of his capitals.[10] In either 703[11] or 706,[12] the ruler Xiong Tong became the ruler of Chu.

Spring and Autumn period

[edit]

Under the reign of King Zhuang, Chu reached the height of its power and its ruler was considered one of the five Hegemons of the era. After a number of battles with neighboring states, sometime between 695 and 689 BC, the Chu capital moved south-east from Danyang to Ying. Chu first consolidated its power by absorbing other states in its original area (modern Hubei), then it expanded into the north towards the North China Plain. In the summer of 648 BC, the State of Huang was annexed by the state of Chu.[13]

The threat from Chu resulted in multiple northern alliances under the leadership of Jin. These alliances kept Chu in check, and the Chu kingdom lost their first major battle at the Chengpu in 632 BC. During the 6th century BC, Jin and Chu fought numerous battles over the hegemony of central plain. In 597 BC, Jin was defeated by Chu in the battle of Bi, causing Jin's temporary inability to counter Chu's expansion. Chu strategically used the state of Zheng as its representative in the central plain area, through the means of intimidation and threats, Chu forced Zheng to ally with itself. On the other hand, Jin had to balance out Chu's influence by repeatedly allying with Lu, Wey, and Song. The tension between Chu and Jin did not loosen until the year of 579 BC when a truce was signed between the two states.[14]

At the beginning of the sixth century BC, Jin strengthened the state of Wu near the Yangtze delta to act as a counterweight against Chu. Wu defeated Qi and then invaded Chu in 506 BC. Following the Battle of Boju, it occupied Chu's capital at Ying, forcing King Zhao to flee to his allies in Yun and "Sui". King Zhao eventually returned to Ying but, after another attack from Wu in 504 BC, he temporarily moved the capital into the territory of the former state of Ruo. Chu began to strengthen Yue in modern Zhejiang to serve as allies against Wu. Yue was initially subjugated by King Fuchai of Wu until he released their king Goujian, who took revenge for his former captivity by crushing and completely annexing Wu.

Warring States period

[edit]Freed from its difficulties with Wu, Chu annexed Chen in 479 BC and overran Cai to the north in 447 BC. By the end of the 5th century BC, the Chu government had become very corrupt and inefficient, with much of the state's treasury used primarily to pay for the royal entourage. Many officials had no meaningful task except taking money and Chu's army, while large, was of low quality.

In the late 390s BC, King Dao of Chu made Wu Qi his chancellor. Wu's reforms began to transform Chu into an efficient and powerful state in 389 BC, as he lowered the salaries of officials and removed useless officials. He also enacted building codes to make the capital Ying seem less barbaric. Despite Wu Qi's unpopularity among Chu's ruling class, his reforms strengthened the king and left the state very powerful until the late 4th century BC, when Zhao and Qin were ascendant. Chu's powerful army once again became successful, defeating the states of Wei and Yue. Yue was partitioned between Chu and Qi in either 334[citation needed] or 333 BC.[15] However, the officials of Chu wasted no time in their revenge and Wu Qi was assassinated at King Dao's funeral in 381 BC. Prior to Wu's service in the state of Chu, Wu lived in the state of Wei, where his military analysis of the six opposing states was recorded in his magnum opus, The Book of Master Wu. Of Chu, he said:

The Chu people are soft and weak. Their lands stretch far and wide, and the government cannot effectively administer the expanse. Their troops are weary and although their formations are well-ordered, they do not have the resources to maintain their positions for long. To defeat them, we must strike swiftly, unexpectedly and retreat quickly before they can counter-attack. This will create unease in their weary soldiers and reduce their fighting spirit. Thus, with persistence, their army can be defeated.

— Wu Qi, Wuzi

During the late Warring States period, Chu was increasingly pressured by Qin to its west, especially after Qin enacted and preserved the Legalistic reforms of Shang Yang. In 241 BC, five of the seven major warring states–Chu, Zhao, Wei, Yan and Han–formed an alliance to fight the rising power of Qin. King Kaolie of Chu was named the leader of the alliance and Lord Chunshen the military commander. According to historian Yang Kuan, the Zhao general Pang Nuan (庞煖) was the actual commander in the battle. The allies attacked Qin at the strategic Hangu Pass but were defeated. King Kaolie blamed Lord Chunshen for the loss and began to mistrust him. Afterwards, Chu moved its capital east to Shouchun, farther away from the threat of Qin.

As Qin expanded into Chu's territory, Chu was forced to expand southwards and eastwards, absorbing local cultural influences along the way. Lu was conquered by King Kaolie in 249 BC. By the late 4th century BC, however, Chu's prominent status had fallen into decay. As a result of several invasions headed by Zhao and Qin, Chu was eventually completely wiped out by Qin.

Defeat

[edit]The Chu state was completely eradicated by the Qin dynasty.

According to the Records of the Warring States, a debate between the Diplomat strategist Zhang Yi and the Qin general Sima Cuo led to two conclusions concerning the unification of China. Zhang Yi argued in favor of conquering Han and seizing the Mandate of Heaven from the powerless Zhou king would be wise. Sima Cuo, however, considered that the primary difficulty was not legitimacy but the strength of Qin's opponents; he argued that "conquering Shu is conquering Chu" and, "once Chu is eliminated, the country will be united".

The importance of Shu in the Sichuan Basin was its great agricultural output and its control over the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, leading directly into the Chu heartland. King Huiwen of Qin opted to support Sima Cuo. In 316 BC, Qin invaded and conquered Shu and nearby Ba, expanding downriver in the following decades. In 278 BC, the Qin general Bai Qi finally conquered Chu's capital at Ying. Following the fall of Ying, the Chu government moved to various locations in the east until settling in Shouchun in 241 BC. After a massive two-year struggle, Bai Qi lured the main Zhao force of 400,000 men onto the field, surrounding them and forcing their surrender at Changping in 260 BC. The Qin army massacred their prisoners, removing the last major obstacle to Qin dominance over the Chinese states.

By 225 BC, only four kingdoms remained: Qin, Chu, Yan, and Qi. Chu had recovered sufficiently to mount serious resistance. Despite its size, resources, and manpower, though, Chu's corrupt government worked against it. In 224 BC, Ying Zheng called for a meeting with his subjects to discuss his plans for the invasion of Chu. Wang Jian said that the invasion force needed to be at least 600,000 strong, while Li Xin thought that less than 200,000 men would be sufficient. Ying Zheng ordered Li Xin and Meng Wu to lead the army against Chu.[citation needed]

The Chu army, led by Xiang Yan, secretly followed Li Xin's army for three days and three nights, before launching a surprise offensive and destroying Li Xin army. Upon learning of Li's defeat, Ying Zheng replaced Li with Wang Jian, putting Wang in command of the 600,000-strong army he had requested earlier and placing Meng Wu beneath him as a deputy. Worried that the Qin tyrant might fear the power he now possessed and order him executed upon some pretense, Wang Jian constantly sent messengers back to the king in order to remain in contact and reduce the king's suspicion.

Wang Jian's army passed through southern Chen (陳; present-day Huaiyang in Henan) and made camp at Pingyu. The Chu armies under Xiang Yan used their full strength against the camp but failed. Wang Jian ordered his troops to defend their positions firmly but avoid advancing further into Chu territory. After failing to lure the Qin army into an attack, Xiang Yan ordered a retreat; Wang Jian seized this opportunity to launch a swift assault. The Qin forces pursued the retreating Chu forces to Qinan (蕲南; northwest of present-day Qichun in Hubei) and Xiang Yan was either killed in the action or committed suicide following his defeat.[citation needed]

The next year, in 223 BC, Qin launched another campaign and captured the Chu capital Shouchun. King Fuchu was captured and his state annexed.[16] The following year, Wang Jian and Meng Wu led the Qin army against Wuyue around the mouth of the Yangtze, capturing the descendants of the royal family of Yue.[16] These conquered territories became the Kuaiji Prefecture of the Qin Empire.

At their peak, Chu and Qin together fielded over 1,000,000 troops, more than the massive Battle of Changping between Qin and Zhao 35 years before. The excavated personal letters of two regular Qin soldiers, Hei Fu (黑夫) and Jing (惊), tell of a protracted campaign in Huaiyang under Wang Jian. Both soldiers wrote letters requesting supplies of clothing and money from home to sustain the long waiting campaign.[17]

Qin and Han dynasties

[edit]

The Chu populace in areas conquered by Qin openly ignored the stringent Qin laws and governance, as recorded in the excavated bamboo slips of a Qin administrator in Hubei. Chu aspired to overthrow the painful yoke of Qin rule and re-establish a separate state. The attitude was captured in a Chinese expression about implacable hostility: "Though Chu has but three clans,[18] Qin shall fall by Chu's hand" (楚雖三戶, 亡秦必楚).[19]

After Ying Zheng declared himself the First Emperor (Shi Huangdi) and reigned briefly, the people of Chu and its former ruling house organized the first violent insurrections against the new Qin administration. They were especially resentful of the Qin corvée; folk poems record the mournful sadness of Chu families whose men worked in the frigid north to construct the Great Wall of China.

The Dazexiang Uprising occurred in 209 BC under the leadership of a Chu peasant, Chen Sheng, who proclaimed himself "King of Rising Chu" (Zhangchu). This uprising was crushed by the Qin army but it inspired a new wave of other rebellions. One of the leaders, Jing Ju of Chu, proclaimed himself the new king of Chu. Jing Ju was defeated by another rebel force under Xiang Liang. Xiang installed Xiong Xin, a scion of Chu's traditional royal family, on the throne of Chu under the regnal name King Huai II. In 206 BC, after the fall of the Qin Empire, Xiang Yu, Xiang Liang's nephew, proclaimed himself the "Hegemon-King of Western Chu" and promoted King Huai II to "Emperor Yi". He subsequently had Yi assassinated. Xiang Yu then engaged with Liu Bang, another prominent anti-Qin rebel, in a long struggle for supremacy over the lands of the former Qin Empire, which became known as the Chu–Han Contention. The conflict ended in victory for Liu Bang: he proclaimed the Han dynasty and was later honored with the temple name Gaozu, while Xiang Yu committed suicide in defeat.

Liu Bang immediately enacted a more traditional and less intrusive administration than the Qin before him, made peace with the Xiongnu through heqin intermarriages, rewarded his allies with large fiefdoms, and allowed the population to rest from centuries of warfare. The core Chu territories centered in Pengcheng was granted first to general Han Xin and then to Liu Bang's brother Liu Jiao as the Kingdom of Chu. By the time of Emperor Wu of Han, the southern folk culture and aesthetics were mixed with the Han-sponsored Confucian tradition and Qin-influenced central governance to create a distinct "Chinese" culture.

Culture

[edit]

Based on the archaeological finds, Chu's culture was initially quite similar to that of the other Zhou states of the Yellow River basin. However, subsequently, Chu absorbed indigenous elements from the Baiyue lands that it conquered to the south and east, developing a blended culture compared to the northern plains.

During the Western Zhou period, the difference between the culture of Chu and the Central Plains states to the north was negligible. Only in the late Spring and Autumn period does Chu culture begin to diverge, preserving some older aspects of the culture and developing new phenomena. It also absorbed some elements from annexed areas. The culture of Chu had significant internal diversity from locality to locality.[20] Chu, like Qin and Yan, was often described as being not as cultured by people in the Central plains. However, this image originated with the later development of Chu relative to the Central plains, and the stereotype was retrospectively cultivated by Confucian scholars in the Qin dynasty, to indirectly criticise the ruling regime, and the Han dynasty as a means of curbing their ideological opponents who were associated with such cultural practices.[21] As the founder of the Han dynasty was from the state, Chu culture would later become a basis of the culture of the later Han dynasty, along with that of the Qin dynasty's and other preceding states' from the Warring States period.[22]

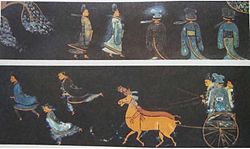

Early Chu burial offerings consisted primarily of bronze vessels in the Zhou style. The bronze wares of the state of Chu also have their own characteristics. For example, the bronze Jin (altar table) unearthed from the Chu tomb in Xichuan, Henan Province are complex in shape. Dated to the mid sixth century BC, it was one of the early confirmed lost-wax cast artifacts discovered in China proper.[23] Later Chu burials, especially during the Warring States, featured distinct burial objects, such as colorful lacquerware, iron, and silk, accompanied by a reduction in bronze vessel offerings. A common Chu motif was the vivid depiction of wildlife, mystical animals, and natural imagery, such as snakes, dragons, phoenixes, tigers, and free-flowing clouds and serpent-like beings. Some archaeologists speculate that Chu may have had cultural connections to the previous Shang dynasty, since many motifs used by Chu appeared earlier at Shang sites such as serpent-tailed gods.

Another common Chu idea was the worship of gibbons and other animals perceived to have auspicious amounts of qi.[24]

Later Chu culture was known for its affinity for shamans. The Chu culture and government supported Taoism[24] and native shamanism supplemented with some Confucian glosses on Zhou ritual. Chu people affiliated themselves with the god of fire Zhurong in Chinese mythology. For this reason, fire worshiping and red coloring were practiced by Chu people.[25]

The naturalistic and flowing art, the Songs of Chu, historical records, excavated bamboo documents such as the Guodian slips, and other artifacts reveal heavy Taoist and native folk influence in Chu culture. The disposition to a spiritual, often pleasurable and decadent lifestyle, and the confidence in the size of the Chu realm led to the inefficiency and eventual destruction of the Chu state by the ruthless Legalist state of Qin. Even though the Qin realm lacked the vast natural resources and waterways of Chu, the Qin government maximized its output under the efficient minister Shang Yang, installing a meritocracy focused solely on agricultural and military might.

Archaeological evidence shows that Chu music was annotated differently from Zhou. Chu music also showed an inclination for using different performance ensembles, as well as unique instruments. In Chu, the se was preferred over the zither, while both instruments were equally preferred in the northern Zhou states.

Chu came into frequent contact with other peoples in the south, most notably the Ba, Yue, and the Baiyue. Numerous burials and burial objects in the Ba and Yue styles have been discovered throughout the territory of Chu, co-existing with Chu-style burials and burial objects.

Some archaeological records of the Chu appear at Mawangdui. After the Han dynasty, some Confucian scholars considered Chu culture with distaste, criticizing the "lewd" music and shamanistic rituals associated with Chu culture.

Chu artisanship includes color, especially the lacquer woodworks. Red and black pigmented lacquer were most used. Silk-weaving also attained a high level of craftsmanship, creating lightweight robes with flowing designs. These examples (as at Mawangdui) were preserved in waterlogged tombs where the lacquer did not peel off over time and in tombs sealed with coal or white clay. Chu used the calligraphic script called "Birds and Worms" style, which was borrowed by the Wu and Yue states. It has a design that embellishes the characters with motifs of animals, snakes, birds, and insects. This is another representation of the natural world and its liveliness. Chu produced broad bronze swords that were similar to Wuyue swords but not as intricate.

Chu created a riverine transport system of boats augmented by wagons. These are detailed in bronze tallies with gold inlay regarding trade along the river systems connecting with those of the Chu capital at Ying.

Linguistic influences

[edit]Although bronze inscriptions from the ancient state of Chu show little linguistic differences from the "Elegant Speech" (yǎyán 雅言) during the Eastern Zhou period,[26] the variety of Old Chinese spoken in Chu has long been assumed to reflect lexical borrowings and syntactical interferences from non-Sinitic substrates, which the Chu may have acquired as a result of its southern migration into what Tian Jizhou believed to be a Kra–Dai or (para-) Hmong–Mien area in southern China.[27][28] Recent excavated texts, corroborated by dialect words recorded in the Fangyan, further demonstrated substrate influences, but there are competing hypotheses on their genealogical affiliation.[29][30]

- Aberrant early Chinese dialect, originally from the North[31]

- Austroasiatic (Norman & Mei 1976, Boltz 1999)

- Hmong–Mien (Erkes 1930, Long & Ma 1983, Brooks 2001, Sagart et al. 2005)[32]

- Kra–Dai (Liu Xingge 1988, Zhengzhang Shangfang 2005)

- Tibeto-Burman (Zhang Yongyan 1992, Zhou Jixu 2001)

- Mixture of Austroasiatic, Hmong-Mien and Tibeto-Burman (Pullyblank 1983, Schuessler 2004 & 2007)

- Unknown

Noticing that both 荆 Jīng and 楚 Chǔ refer to the thorny chaste tree (genus Vitex), Schuessler (2007) proposes two Austroasiatic comparanda:[33]

- 楚 Chǔ < Old Chinese *tshraʔ is comparable to Proto-Monic *jrlaaʔ "thorn, thorny bamboo (added to names of thorny plants)", Khmu /cǝrlaʔ/, Semai /jǝrlaaʔ/, all descending from Proto-Austroasiatic *ɟrla(:)ʔ "thorn";[34]

- 荆 Jīng < Old Chinese *kreŋ is comparable to Khmer ជ្រាំង crĕəng “to bristle” and ប្រែង praeng “bristle”, with Chinese initial *k- possibly being a noun-forming prefix.

Bureaucracy

[edit]

The Mo'ao (莫敖) and the Lingyin (令尹) were the top government officials of Chu. Sima was the military commander of Chu's army. Lingyin, Mo'ao and Sima were the San Gong (三公) of Chu. In the Spring and Autumn period, Zuoyin (左尹) and Youyin (右尹) were added as the undersecretaries of Lingyin. Likewise, Sima (司馬) was assisted by Zuosima (左司馬) and Yousima (右司馬) respectively. Mo'ao's status was gradually lowered while Lingyin and Sima became more powerful posts in the Chu court.[35]

Ministers whose functions vary according to their titles were called Yin (尹). For example: Lingyin (Prime minister), Gongyin (Minister of works), and Zhenyin were all suffixed by the word "Yin".[36] Shenyin (沈尹) was the minister of religious duties or the high priest of Chu, multiple entries in Zuo Zhuan indicated their role as oracles.[37] Other Yins recorded by history were: Yuyin, Lianyin, Jiaoyin, Gongjiyin, Lingyin, Huanlie Zhi Yin (Commander of Palace guards) and Yueyin (Minister of Music). In counties and commanderies, Gong (公), also known as Xianyin (minister of county) was the chief administrator.[38]

In many cases, positions in Chu's bureaucracy were hereditarily held by members of a cadet branch of Chu's royal house of Mi. Mo'ao, one of the three chancellors of Chu, was exclusively chosen from Qu (屈) clan. During the early spring and autumn period and before the Ruo'ao rebellion, Lingyin was a position held by Ruo'aos, namely Dou (鬭) and Cheng (成).[14]

Geography

[edit]Progenitors of Chu such as viscount Xiong Yi were said to originate from the Jing Mountains; a chain of mountains located in today's Hubei province. Rulers of Chu systematically migrated states annexed by Chu to the Jing mountains in order to control them more efficiently. East of Jing mountains are the Tu (塗) mountains. In the north-east part of Chu are the Dabie mountains; the drainage divide of Huai river and Yangtse river. The first capital of Chu, Danyang (丹陽) was located in today's Zhijiang, Hubei province. Ying (郢), one of the later capitals of Chu, is known by its contemporary name Jingzhou. In Chu's northern border lies the Fangcheng mountain. Strategically, Fangcheng is an ideal defense against states of central plain. Due to its strategic value, numerous castles were built on the Fangcheng mountain.[14]

Yunmeng Ze in Jianghan Plain was an immense freshwater lake that historically existed in Chu's realm, It was crossed by Yanzi river, the northern Yunmeng was named Meng (夢), the southern Yunmeng was known as Yun (雲). The lake's body covers parts of today's Zhijiang, Jianli, Shishou, Macheng, Huanggang, and Anlu.[14]

Shaoxi Pass was an important outpost in the mountainous western border of Chu. It was located in today's Wuguan town of Danfeng County, Shaanxi. Any forces that marched from the west, mainly from Qin, to Chu's realm would have to pass Shaoxi.[14]

List of states annexed by Chu

[edit]- 863 BC E

- 704 BC Quan

- 690 BC Luo

- 688–680 BC Shen

- 684–680 BC Xi

- 678 BC Deng

- 648 BC Huang

- after 643 BC Dao

- 623 BC Jiang (江)

- 622 BC Liao

- 622 BC Lù (六).[39]

- after 622 BC Ruo

- 617 BC Jiang (蔣)

- 611 BC Yong

- 601 BC Shuliao[39]

- Sometime in the 6th century BC Zhongli[40]

- after 506 BC Sui

- 574 BC Shuyong

- 538 BC Lai (賴國)

- 512 BC Xu

- 479 BC Chen

- 445 BC Qi

- 447 BC Cai

- 431 BC Ju

- after 418 BC Pi

- About 348 BC Zou

- 334 BC Yue

- 249 BC Lu

Rulers

[edit]- Jilian (季連), married Bi Zhui (妣隹), granddaughter of Shang dynasty king Pangeng; adopted Mi (芈) as ancestral name

- Yingbo (𦀚伯) or Fuju (附沮), son of Jilian

- Yuxiong (鬻熊), ruled 11th century BC: also called Xuexiong (穴熊), teacher of King Wen of Zhou

- Xiong Li (熊麗), ruled 11th century BC: son of Yuxiong, first use of clan name Yan (酓), later written as Xiong (熊)

- Xiong Kuang (熊狂), ruled 11th century BC: son of Xiong Li

- Viscounts

- Xiong Yi (熊繹), ruled 11th century BC: son of Xiong Kuang, enfeoffed by King Cheng of Zhou

- Xiong Ai (熊艾), ruled c. 977 BC: son of Xiong Yi, defeated and killed King Zhao of Zhou

- Xiong Dan (熊䵣), ruled c. 941 BC: son of Xiong Ai, defeated King Mu of Zhou

- Xiong Sheng (熊勝), son of Xiong Dan

- Xiong Yang (熊楊), younger brother of Xiong Sheng

- Xiong Qu (熊渠), son of Xiong Yang, gave the title king to his three sons

- Xiong Kang (熊康), son of Xiong Qu. Shiji says Xiong Kang died early without ascending the throne, but the Tsinghua Bamboo Slips recorded him as the successor of Xiong Qu.[42]

- Xiong Zhi (熊摯), son of Xiong Kang, abdicated due to illness[42][43]

- Xiong Yan (elder) (熊延), ruled ?–848 BC: younger brother of Xiong Zhi

- Xiong Yong (熊勇), ruled 847–838 BC: son of Xiong Yan

- Xiong Yan (younger) (熊嚴), ruled 837–828 BC: brother of Xiong Yong

- Xiong Shuang (熊霜), ruled 827–822 BC: son of Xiong Yan

- Xiong Xun (熊徇), ruled 821–800 BC: youngest brother of Xiong Shuang

- Xiong E (熊咢), ruled 799–791 BC: son of Xiong Xun

- Ruo'ao (若敖) (Xiong Yi 熊儀), ruled 790–764 BC: son of Xiong E

- Xiao'ao (霄敖) (Xiong Kan 熊坎), ruled 763–758 BC: son of Ruo'ao

- Fenmao (蚡冒) (Xiong Xuan 熊眴) ruled 757–741 BC: son of Xiao'ao

- Kings

- King Wu of Chu (楚武王) (Xiong Da 熊達), ruled 740–690 BC: either younger brother or younger son of Fenmao, murdered son of Fenmao and usurped the throne. Declared himself first king of Chu.

- King Wen of Chu (楚文王) (Xiong Zi 熊貲), ruled 689–677 BC: son of King Wu, moved the capital to Ying

- Du'ao (堵敖) or Zhuang'ao (莊敖) (Xiong Jian 熊艱), ruled 676–672 BC: son of King Wen, killed by younger brother, the future King Cheng

- King Cheng of Chu (楚成王) (Xiong Yun 熊惲), ruled 671–626 BC: brother of Du'ao, defeated by the state of Jin at the Battle of Chengpu. Husband to Zheng Mao. He was murdered by his son, the future King Mu

- King Mu of Chu (楚穆王) (Xiong Shangchen 熊商臣) ruled 625–614 BC: son of King Cheng

- King Zhuang of Chu (楚莊王) (Xiong Lü 熊侶) ruled 613–591 BC: son of King Mu. Defeated the State of Jin at the Battle of Bi, and was recognized as a Hegemon.

- King Gong of Chu (楚共王) (Xiong Shen 熊審) ruled 590–560 BC: son of King Zhuang. Defeated by Jin at the Battle of Yanling.

- King Kang of Chu (楚康王) (Xiong Zhao 熊招) ruled 559–545 BC: son of King Gong

- Jia'ao (郟敖) (Xiong Yuan 熊員) ruled 544–541 BC: son of King Kang, murdered by his uncle, the future King Ling.

- King Ling of Chu (楚靈王) (Xiong Wei 熊圍, changed to Xiong Qian 熊虔) ruled 540–529 BC: uncle of Jia'ao and younger brother of King Kang, overthrown by his younger brothers and committed suicide.

- Zi'ao (訾敖) (Xiong Bi 熊比) ruled 529 BC (less than 20 days): younger brother of King Ling, committed suicide.

- King Ping of Chu (楚平王) (Xiong Qiji 熊弃疾, changed to Xiong Ju 熊居) ruled 528–516 BC: younger brother of Zi'ao, tricked Zi'ao into committing suicide.

- King Zhao of Chu (楚昭王) (Xiong Zhen 熊珍) ruled 515–489 BC: son of King Ping. The State of Wu captured the capital Ying and he fled to the State of Sui.

- King Hui of Chu (楚惠王) (Xiong Zhang 熊章) ruled 488–432 BC: son of King Zhao. He conquered the states of Cai and Chen. The year before he died, Marquis Yi of Zeng died, so he made a commemorative bell and attended the Marquis's funeral at Suizhou.

- King Jian of Chu (楚簡王) (Xiong Zhong 熊中) ruled 431–408 BC: son of King Hui

- King Sheng of Chu (楚聲王) (Xiong Dang 熊當) ruled 407–402 BC: son of King Jian

- King Dao of Chu (楚悼王) (Xiong Yi 熊疑) ruled 401–381 BC: son of King Sheng. He made Wu Qi chancellor and reformed the Chu government and army.

- King Su of Chu (楚肅王) (Xiong Zang 熊臧) ruled 380–370 BC: son of King Dao

- King Xuan of Chu (楚宣王) (Xiong Liangfu 熊良夫) ruled 369–340 BC: brother of King Su. Defeated and annexed the Zuo state around 348 BC.

- King Wei of Chu (楚威王) (Xiong Shang 熊商) ruled 339–329 BC: son of King Xuan. Defeated and partitioned the Yue state with Qi state.

- King Huai of Chu (楚懷王) (Xiong Huai 熊槐) ruled 328–299 BC: son of King Wei, was tricked and held hostage by the State of Qin until death in 296 BC

- King Qingxiang of Chu (楚頃襄王) (Xiong Heng 熊橫) ruled 298–263 BC: son of King Huai. As a prince, one of his elderly tutors was buried at the site of the Guodian Chu Slips in Hubei. The Chu capital of Ying was captured and sacked by Qin.

- King Kaolie of Chu (楚考烈王) (Xiong Yuan 熊元) ruled 262–238 BC: son of King Qingxiang. Moved capital to Shouchun.

- King You of Chu (楚幽王) (Xiong Han 熊悍) ruled 237–228 BC: son of King Kaolie.

- King Ai of Chu (楚哀王) (Xiong You 熊猶 or Xiong Hao 熊郝) ruled 228 BC: brother of King You, killed by Fuchu

- Fuchu (楚王負芻) (熊負芻 Xiong Fuchu) ruled 227–223 BC: brother of King Ai. Captured by Qin troops and deposed

- Lord Changping (昌平君) ruled 223 BC (Chu conquered by Qin): brother of Fuchu, killed in battle against Qin

- Others

- Chen Sheng (陳勝) as King Yin of Chu (楚隱王) ruled 210–209 BC

- Jing Ju (景駒) as King Jia of Chu 楚假王 (Jia for fake) ruled 209–208 BC

- Xiong Xin (熊心) as Emperor Yi of Chu (楚義帝) (originally King Huai II 楚後懷王) ruled 208–206 BC: grandson or great-grandson of King Huai

- Xiang Yu (項羽) as Hegemon-King of Western Chu (西楚霸王) ruled 206–202 BC

People

[edit]- Qu Yuan, poet who committed suicide

- Lord Chunshen, one of the Four Lords of the Warring States

- Xiang Yu, the Hegemon-King of Western Chu who defeated the Qin at Julu and vied with Liu Bang in the Chu–Han Contention

- Liu Bang, later citizen of the Qin dynasty and then founder of the Han dynasty

Astronomy

[edit]In traditional Chinese astronomy, Chu is represented by a star in the "Twelve States" asterism, part of the "Girl" lunar mansion in the "Black Turtle" symbol. Opinions differ, however, as to whether that star is Phi[44] or 24 Capricorni.[45] It is also represented by the star Epsilon Ophiuchi in the "Right Wall" asterism in the "Heavenly Market" enclosure.[46][47]

Biology

[edit]The virus taxa Chuviridae and Jingchuvirales are named after Chǔ.[48]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "楚都丹陽". Archived from the original on 2011-07-07.

- ^ "Chu". Encyclopedia Britannica. 3 November 2023.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 332.

- ^ "河南库区发掘工作圆满结束,出土文物已通过验收". 合肥晚报. 2011-01-25. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11.

- ^ "科大考古队觅宝千余件". 凤凰网. 2011-01-25. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich. (2018) "The Regional State of Chu 楚" in ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- ^ Zhang, Zhengming. (2019) A History Of Chu (Volume 1) Honolulu: Enrich Professional Publishing. p. 46-47

- ^ a b c Sima Qian. "楚世家 (House of Chu)". Records of the Grand Historian (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Pines, Yuri (2017). CHU IDENTITY AS SEEN FROM ITS MANUSCRIPTS: A REEVALUATION. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9788184246834.

- ^ "Yu Ding: Evidence of the Extermination of the State of E during the Western Zhou Dynasty (禹鼎:西周灭鄂国的见证)" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- ^ Lothar von Falkenahausen in Cambridge History of Ancient China, 1999, page 516

- ^ Cho-Yun Hsu in Cambridge History of Ancient China, 1999, page 556

- ^ "5.僖公 BOOK V. DUKE XI". The Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (in Chinese). Translated by James Legge (with modifications from Andrew Miller). Retrieved 28 March 2018.

from Zuo zhuan, twelfth year of Duke Xi of Lu《左傳·僖公十二年》: "黃人恃諸侯之睦于齊也,不共楚職,曰,自郢及我,九百里,焉能害我。夏,楚滅黃。 'The people of Huang, relying on the friendship of the States with Qi, did not render the tribute which was due from them to Chu, saying "From Ying [the capital of Chu] to us is 900 li; what harm can Chu do to us?" This summer, Chu extinguished Huang."

- ^ a b c d e Gu, Donggao (1993). 春秋大事表. Zhonghua Book Company. pp. 940–945, 972, 1140, 2055–2066. ISBN 9787101012187.

- ^ Brindley (2015), p. 86.

- ^ a b Li and Zheng, page 188

- ^ "The Warring States" (in Chinese). Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ Traditionally taken to be the Qu (屈), Jing (景), and Zhao (昭).

- ^ Sima Qian. Records of the Grand Historian, "Biography of Xiang Yu" (項羽本紀).

- ^ Constance A., Cook (1999). Defining Chu : Image and Reality in Ancient China. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 3, 21–22, 32, 168. ISBN 0824818857.

- ^ Constance A., Cook (1999). Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 1–4, 149, 151–165. ISBN 0824818857.

- ^ Constance A., Cook (1999). Defining Chu : Image and Reality in Ancient China. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 140–150. ISBN 0824818857.

- ^ Peng, Peng (2020). Metalworking in Bronze Age China: The Lost-Wax Process By Peng Peng. cambria Press. ISBN 9781604979626.

- ^ a b Walker, Hera S. (September 1998). "Indigenous or Foreign? A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. University of Pennsylvania. pp. 53–54.

- ^ Lin, Qingzhang (2008). 中國學術思想研究輯刊: 二編, Volume 6. p. 176. ISBN 9789866528071.

- ^ Yù, Suíshēng (1993). Liăng-Zhōu jīnwén yùnwén he xiān-Qín 'Chŭ-yīn (2 ed.). Journal of Chuxiong Teacher's College. pp. 105–109.[permanent dead link]

- ^ LaPolla, Randy J. (2010-01-01). "Language Contact and Language Change in the History of the Sinitic Languages". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. The Harmony of Civilization and Prosperity for All: Selected Papers of Beijing Forum(2004-2008). 2 (5): 6858–6868. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.05.036. ISSN 1877-0428.

- ^ Tian, Jizhou (1989). "Chuguo ji qi minzu (The country of Chu and its nationalities)". Zhongguo Minzushi Yanjiu. 2: 1–17.

- ^ Behr 2009.

- ^ Chamberlain 2016, p. 67.

- ^ You Rujie 1992, Dong Kun 2006 etc.

- ^ Ye, Xiaofeng (2014). "上古楚语中的南亚语成分 (Austroasiatic elements in ancient Chu dialect)" (PDF). Minzu Yuwen. 3: 28–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-01-14. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- ^ Schuessler, Axel. 2007. An Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. p. 193, 316-7

- ^ Sidwell, Paul (2024). "500 Proto Austroasiatic Etyma: Version 1.0". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 17 (1): viii.

- ^ 中國早期國家性質. Zhishufang Press. 2003. p. 372. ISBN 9789867938176.

- ^ Song, Zhiying (2012). 《左传》研究文献辑刊(全二十二册). Beijing: National Library of China publishing house. ISBN 9787501346158.

- ^ Tian, Chengfang (Autumn 2008). "從新出文字材料論楚沈尹氏之族屬源流". Jianbo (简帛). Archived from the original on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2017-09-28 – via 简帛网.

- ^ Hong, Gang (2012). 财政史研究. 中国财政经济出版社.

- ^ a b Gongyang Zhuan, Duke Wen, 6th year of, Duke Xuan, 8th year of

- ^ Anhui Provincial Institute (2015), p. 83.

- ^ See also, the Tsinghua Bamboo Slips.

- ^ a b Ziju (子居). 清华简《楚居》解析 (in Chinese). jianbo.org. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Note: Shiji calls him Xiong Zhihong (熊摯紅), and says his younger Xiong Yan killed him and usurped the throne. However, Zuo Zhuan and Guoyu both say that Xiong Zhi abdicated due to illness and was succeeded by brother Xiong Yan. Shiji also says he was the younger brother of Xiong Kang, but historians generally agree that he was the son of Xiong Kang.

- ^ Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy. "天文教育資訊網 Archived 2011-05-22 at the Wayback Machine". 4 Jul 2006. (in Chinese)

- ^ Allen, Richard. "Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning: Capricornus".

- ^ "Richard Hinckley Allen: Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning: Ophiuchus". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ AEEA. "天文教育資訊網 Archived 2011-05-22 at the Wayback Machine". 24 Jun 2006. (in Chinese)

- ^ Wolf, Yuri; Krupovic, Mart; Zhang, Yong Zhen; Maes, Piet; Dolja, Valerian; Koonin, Eugene V.; Kuhn, Jens H. "Megataxonomy of negative-sense RNA viruses". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Archived from the original (docx) on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Anhui Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and Bengbu Museum (June 2015). "The Excavation of the tomb of Bai, Lord of the Zhongli State". Chinese Archaeology. 14 (1). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter: 62–85. doi:10.1515/char-2014-0008.

- Baxter, William H.; et al. (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Behr, Wolfgang (2017). "The language of the bronze inscriptions". In Shaughnessy, Edward L. (ed.). Kinship: Studies of Recently Discovered Bronze Inscriptions from Ancient China. The Chinese University Press of Hong Kong. pp. 9–32. ISBN 978-9-629-96639-3.

- Behr, Wolfgang (2009). "Dialects, diachrony, diglossia or all three? Tomb text glimpses into the language(s) of Chǔ". TTW-3, Zürich, 26.-29.VI.2009, "Genius Loci": 1–48.

- Brindley, Erica Fox (2015), Ancient China and the Yue: Perceptions and Identities on the Southern Frontier, c, 400 BC–50 AD, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781107084780.

- Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam". Journal of the Siam Society. 104: 27–77.

- Cook, Constance A.; et al., eds. (January 2004), Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-2905-0.

- Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian (《史記》).

- So, Jenny F. (2000), Music in the Age of Confucius, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, ISBN 0-295-97953-4.

- Zhang Shuyi (2008), Investigation of the Pre-Qin Surname System (《先秦姓氏制度考察》) (in Chinese), Fuzhou: Fujian People's Publishing.

- Zuo Qiuming, Zuo Zhuan (《左传》).

Further reading

[edit]- Miyake, Marc. 2018. Chu and Kra-Dai.

Chu (state)

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Founding

The ruling house of Chu traced its origins to the semi-legendary progenitor Jilian (季連), a descendant of Zhuanxu (a grandson of the Yellow Emperor) through the fire deity Zhurong, adopting the clan name Xiong (熊, "bear").[1] Bamboo slip manuscripts, such as the Chu ju from the Qinghua University collection, record Jilian as descending at Mount Wei, marrying Ancestress Zhui (a daughter of a Shang royal descendant), and fathering sons Cheng and Yuan, emphasizing ties to the preceding Shang dynasty over more distant mythical ancestors like Zhuanxu.[3] These accounts blend mythological genealogy with historical assertions of legitimacy, though archaeological evidence points to indigenous cultural development in the middle Yangzi region predating Zhou influence, featuring distinct bronze styles and settlement patterns distinct from northern Huaxia traditions.[1] The historical founding of Chu as a Zhou vassal state occurred in the early Western Zhou period (c. 1046–771 BCE), when King Cheng of Zhou (r. c. 1042–1021 BCE) enfeoffed Xiong Yi (熊繹), great-grandson of the advisor Yu Xiong (鬻熊) who allegedly aided the Zhou conquest of Shang, with territories in the Han River valley near Mount Jingshan (modern Nanzhang, Hubei).[1][4] Xiong Yi relocated the nascent polity's center to Danyang (modern Zigui, Hubei), receiving the hereditary title of viscount (子, zǐ), which positioned Chu as a peripheral marcher state tasked with managing southern frontiers and non-Zhou tribes, rather than a core feudal domain.[1] This enfeoffment integrated Chu into the Zhou feudal order, though its rulers soon asserted autonomy by claiming the title of king (王, wáng), reflecting limited central oversight and early tensions, as evidenced by King Zhao of Zhou's failed southern campaign against Chu around 977 BCE.[1] Early Chu under Xiong Yi and successors like Xiong Qu focused on consolidating control over the middle Yangzi and Han River basins, incorporating local polities such as Yong and Yangyue through conquest, while archaeological sites reveal a material culture blending Zhou ritual bronzes with regional lacquerware and shamanistic elements, underscoring gradual Sinicization amid indigenous roots.[1] These foundations laid the groundwork for Chu's expansion, distinguishing it from the ritual orthodoxy of Zhou heartland states due to its geographic isolation and adaptive governance.[3]Expansion during Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn Periods

During the Western Zhou period (c. 1046–771 BCE), the state of Chu, enfeoffed in the middle Yangtze valley by King Cheng of Zhou (r. 1116–1079 BCE), experienced limited territorial expansion centered on consolidation rather than aggressive conquest.[1] The early rulers, including Xiong Yi in the late 11th century BCE, established settlements near Mount Jingshan and Danyang in modern Hubei province.[1] Under Xiong Qu (dates uncertain, c. 9th–8th century BCE), Chu extended its control along the middle Yangtze and Han Rivers, annexing small statelets such as Yong and Yangyue.[1] These gains incorporated local non-Zhou tribes, laying the foundation for later growth but remaining peripheral to the Zhou heartland.[1] The Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BCE) marked Chu's rapid expansion, transforming it from a southern periphery state into a major power challenging northern hegemons. King Wu (r. 741–690 BCE) initiated this phase by conquering the state of Sui and subjugating the hundred Pu tribes south of the Yangtze River, securing access to the Huai River basin.[1] His successor, King Wen (r. 690–677 BCE), continued northward, annexing Xi (modern Xixian, Henan), Shen (modern Nanyang, Henan), and Deng (modern Xiangfan, Hubei).[1] Under King Cheng (r. 672–626 BCE), Chu absorbed numerous smaller polities including Xu, Xian, Huang, and Ying, while defeating larger rivals; in 656 BCE, it repelled Duke Huan of Qi at Zhaoling (modern Yancheng, Henan), forging a temporary alliance, and in 634 BCE conquered Gu and Kui.[1] King Mu (r. 626–614 BCE) seized Jiang (modern Xixian, Henan) and Lu (modern Lu'an, Anhui), pressuring Chen.[1] The zenith came under King Zhuang (r. 614–591 BCE), who in 597 BCE defeated Jin at Bi (modern Zhengzhou, Henan), conquered Chen (later reinstated), and in 594 BCE annexed Yong (modern Zhushan, Hubei), Shu-Liao (modern Shucheng, Anhui), and Xiao (modern Xuzhou, Jiangsu); further victories included subduing Zheng and triumphing over Jin again at Yanling in 575 BCE.[1] These campaigns extended Chu's domain from the Yangtze basin northward beyond the Huai River, incorporating swathes of modern Henan, Anhui, and Jiangsu, and establishing it as a counterweight to Qi and Jin hegemony.[1]Dominance in the Warring States Period

During the early Warring States period, Chu attained dominance through administrative and military reforms initiated under King Dao (r. 402–381 BCE). Appointing the strategist Wu Qi as chancellor around 389 BCE, Chu implemented policies that centralized authority, diminished the influence of hereditary nobility, and reorganized the military into efficient units based on merit rather than birth. These reforms enabled Chu to launch successful campaigns against northern rivals, including victories over Wei that captured several cities and expanded control into the Huai River plain.[1][5] Under King Wei (r. 340–329 BCE), Chu further consolidated its power by conquering the state of Yue in 333 BCE, in alliance with Qi, thereby annexing vast eastern territories along the Pacific coast and extending influence southward to regions like Dongting and Cangwu. This expansion marked Chu's territorial peak, encompassing approximately one-third of the known Chinese world, from the Yangtze River basin northward to the Huai River and eastward to the sea, surpassing other states in size and resources. The conquest of Yue provided access to maritime trade and timber, bolstering Chu's economy and military capabilities, while its reformed army demonstrated prowess in amphibious and large-scale operations.[1][6][7] Chu's dominance persisted into the reign of King Huai (r. 329–299 BCE), who pursued anti-Qin alliances with states like Qi and Wei, temporarily checking Qin's westward advances and reclaiming areas such as Hanzhong in 312 BCE before subsequent setbacks. The state's cultural and administrative sophistication, evidenced by advanced lacquerware and bronze production, complemented its military strength, positioning Chu as a leading power until mid-century pressures from Qin eroded its northern frontiers.[1]Decline, Defeat, and Absorption into Qin

During the late fourth century BCE, the state of Chu suffered significant setbacks against Qin, beginning under King Huai (r. 329–299 BCE). In 312 BCE, Qin forces defeated Chu at Danyang, seizing Hanzhong and capturing Chu troops, followed by another loss at Lantian in 311 BCE that allowed Han and Wei to encroach on Chu territory.[1] These defeats marked the start of territorial erosion, compounded by King Huai's failed alliances, such as the 318 BCE coalition against Qin that dissolved without decisive gains.[1] King Huai's diplomatic overtures to Qin proved disastrous; in 299 BCE, he was lured to Wuguan Pass under pretense of alliance but captured and detained in Xianyang, where he died in captivity around 296 BCE.[1] His son, King Qingxiang (r. 299–263 BCE), inherited a weakened realm, facing further humiliation in 278 BCE when Qin's general Bai Qi seized Chu's capital Ying, desecrated royal tombs, and forced relocation to Chen.[1][8] This loss of the ancestral center exacerbated internal divisions, as persistent issues with overmighty ministers and fragmented feudal lords undermined central authority, a problem reformers like Wu Qi had identified earlier but failed to resolve durably.[9] Under subsequent rulers, including King Kaolie (r. 263–238 BCE), Chu relocated its capital again to Shouchun amid ongoing pressures, achieving minor recoveries like allying with Wei against Qin in 257 BCE but unable to reverse broader decline.[1] Internal strife intensified with the assassination of prime minister Lord Chunshen in 238 BCE during King You's brief reign (r. 238–228 BCE), followed by rapid successions: King Ai ruled only two months before overthrow, yielding to half-brother King Fuchu (r. 228–223 BCE).[1] Qin's final offensive commenced in 224 BCE, when general Wang Jian led a massive campaign that defeated Chu's army and killed its commander Xiang Yan.[1] By 223 BCE, Wang Jian and Meng Wu captured Shouchun, overran remaining territories, and annexed Chu entirely into the Qin empire as commanderies, ending its independence after centuries of rivalry.[1][8] This absorption facilitated Qin's unification of China by 221 BCE, with Chu's vast southern lands integrated under centralized Legalist administration.[8]Geography and Territorial Control

Core Territories and Natural Features

The core territories of the Chu state were centered in the Jianghan Plain, a fertile alluvial region in modern Hubei Province, formed at the confluence of the Han and Yangtze Rivers. Initially established in the Han River valley around the 11th century BCE, Chu's heartland shifted southeastward into the Yangtze Valley by the 7th century BCE, with the capital relocating from Danyang to Ying, located near present-day Jingzhou. This plain, spanning over 30,000 square kilometers, provided expansive lowlands ideal for intensive agriculture, distinguishing Chu from the more arid northern Zhou states.[1][10] The natural environment of the Jianghan Plain featured a humid subtropical monsoon climate with abundant rainfall, supporting rice cultivation in paddies amid a landscape of rivers, lakes, and wetlands. Surrounding hills and mountains, such as those in the Wushan range to the west, offered natural barriers and resources like timber, while extensive forests yielded lacquer for crafts unique to Chu culture. Large bodies of water, including the ancient Yunmeng Lake that once covered much of the plain during the Chu period, facilitated irrigation but also posed flood risks, shaping settlement patterns around elevated areas.[11][12][13] This geography enabled Chu's early economic self-sufficiency through wet-rice farming and exploitation of aquatic resources, fostering a population density higher than in northern regions by the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BCE). The diverse terrain—plains interspersed with marshes and forested uplands—supported a rich biodiversity, including species adapted to subtropical conditions, which influenced Chu's material culture and shamanistic practices.[1][11]Expansion and Annexed States

Chu's territorial expansion during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods involved the systematic annexation of smaller polities, enabling it to grow from a regional power in the Yangtze valley to one of the largest states in ancient China. Under King Wu (r. c. 740–690 BCE), Chu conquered the states of Xi (in modern Xixian, Henan), Shen (modern Nanyang, Henan), and Deng (modern Xiangfan, Hubei), securing control over the Han River valley and facilitating further northward pushes.[1] These annexations, part of a broader pattern, contributed to Chu subjugating approximately 48 polities overall, with most integrated directly into its administrative structure, providing a reservoir of manpower and resources.[14] In the Warring States period, Chu extended eastward by defeating and partitioning the state of Yue around 333 BCE, incorporating western Yue territories beyond the Yangtze River and advancing into regions now encompassing parts of Zhejiang and Jiangsu. This conquest followed Yue's earlier absorption of Wu and marked Chu's dominance in the lower Yangtze area. Additionally, Chu overran the state of Cai in 447 BCE, though northern expansions were often temporary due to coalitions of rival states.[5] By the mid-4th century BCE, these efforts had expanded Chu's domain to rival the combined size of northern states, though subsequent losses to Qin curtailed further gains.[15]Government and Administration

Bureaucratic Structure

The bureaucratic structure of Chu centered on a monarchical system where the king delegated authority to a small cadre of high officials, with the lingyin (令尹) serving as the chief minister responsible for civil administration, diplomacy, and policy execution, often acting as the king's primary advisor and de facto regent during campaigns.[16][3] This position, prominent from the Spring and Autumn period onward, was frequently held by members of influential clans like the Shen or Qu, reflecting a blend of merit, kinship, and royal favor rather than strict hereditary enfeoffment typical of northern Zhou states.[1] Examples include Zishang, lingyin under King Cheng of Chu (r. 671–626 BCE), who advised on military restraint, and later figures like Ziyu (active ca. 600 BCE), whose decisions influenced major state policies.[1] Complementing the lingyin were two other apex roles forming the core of Chu's elite administration: the mo'ao (莫敖), a senior civil official handling internal affairs and sometimes rivaling the lingyin in influence, and the sima (司馬), the military commander overseeing armed forces, logistics, and defense.[16] These three positions, collectively termed the san gong (三公, "three dukes"), managed the state's executive functions, with the sima also denoted as guozhu (國主, "pillar of state") in Chu, underscoring military centrality amid frequent expansions.[16] Appointments to these roles often sparked clan rivalries, as evidenced by the Ruo Ao clan's rebellion in the late 7th century BCE, quelled by King Zhuang of Chu (r. 613–591 BCE), who then restructured oversight of hydraulic works, taxation, and army buildup to consolidate central control.[17] Chu maintained ten ranks of nobility, higher than the typical Zhou five-grade system, allowing for finer gradations in official hierarchy and land grants, which supported administrative delegation across its vast, non-contiguous territories.[16] Local governance involved appointed prefects and district heads managing agriculture, corvée labor, and tribute collection, evolving toward jun (郡, commanderies) and xian (縣, counties) by the mid-Warring States period (ca. 4th century BCE) to integrate conquered regions like those of Yue and Wu, though clan loyalties persisted, contributing to inefficiencies compared to Qin's merit-based reforms.[16] This structure, less ritual-bound than Zhou orthodoxy, prioritized pragmatic control suited to Chu's southern ecology and shamanistic influences, enabling dominance until Qin's conquest in 223 BCE.Rulers and Dynastic Succession

The ruling house of Chu consisted of the Xiong clan, who traced their ancestry to Yuxiong, a minister under King Wen of Zhou, and ultimately to the mythical emperor Zhuanxu. Xiong Yi, the clan's founding figure, was enfeoffed as Viscount of Chu by King Cheng of Zhou in the early 11th century BCE, settling initially near Mount Jing and establishing a hereditary lordship under Zhou suzerainty. [1] Early rulers bore the title of viscount (zi), reflecting their subordinate status, but the house progressively consolidated power in the Yangtze River basin, adopting the royal title wang from Xiong Tong (posthumously King Wu, r. 741–690 BCE), who usurped the throne and rejected Zhou oversight to assert kingship. [1] Dynastic succession followed patrilineal principles, typically passing to the eldest or designated son, but was frequently disrupted by fraternal rivalries, noble intrigues, and external pressures, leading to short reigns and occasional depositions in the later periods. From the Spring and Autumn era onward, rulers often bore the surname Mi in official contexts while retaining Xiong as the clan name, symbolizing integration into broader Zhou nobility while preserving distinct identity. [1] Instability intensified during the Warring States period, with Qin incursions prompting capital relocations and puppet kings; the final king, Xiong Fuchu, was deposed in 223 BCE following Qin's conquest, ending the dynasty after over 800 years. [1] The following table enumerates the primary rulers, drawing from historical annals:| Personal Name | Posthumous Title | Reign Years (BCE) | Succession Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xiong Yi (熊繹) | (Viscount) | ca. 1040s | Enfeoffed by Zhou King Cheng; son of Xiong Zhong. |

| Xiong Qu (熊渠) | (Viscount) | ca. 10th cent. | Son of Xiong Yi. |

| Xiong Xun (熊徇) | - | 822–800 | Son of Xiong Shuang after disputed succession. |

| Xiong Tong (熊通) | King Wu | 741–690 | Usurped from Fen Mao; first to claim kingship. |

| Xiong Zi (熊貲) | King Wen | 690–677 | Son of King Wu; relocated capital to Ying. |

| Xiong Jian (熊艱) | Du Ao | 677–672 | Son of King Wen; overthrown by brother. |

| Mi Yun (芈惲) | King Cheng (楚成王) | 672–626 | Son of King Wen; brother of Du Ao. |

| Mi Shangchen (芈商臣) | King Mu | 626–614 | Son of King Cheng; forced father's suicide. |

| Mi Lü (芈侶) | King Zhuang | 614–591 | Son of King Mu; achieved hegemony. |

| Mi Shen (芈審) | King Gong | 591–560 | Son of King Zhuang. |

| Mi Zhao (芈招) | King Kang | 560–545 | Son of King Gong. |

| Mi Yuan (芈元) | Jia Ao | 545–541 | Son of King Kang; killed by brother. |

| Mi Qian (芈虔) | King Ling | 541–529 | Brother of Jia Ao. |

| Mi Ju (芈居) | King Ping | 527–516 | Nephew of King Ling. |

| Mi Zhen (芈軫) | King Zhao | 516–489 | Son of King Ping. |

| Mi Zhang (芈章) | King Hui | 489–432 | Son of King Zhao. |

| Mi Zhong (芈中) | King Jian | 432–408 | Son of King Hui; employed reformer Wu Qi. |

| Mi Dang (芈當) | King Sheng | 408–402 | Son of King Jian; assassinated by nobles. |

| Mi Yi (芈怡) | King Dao | 402–381 | Son of King Sheng. |

| Mi Zang (芈臧) | King Su | 381–370 | Son of King Dao. |

| Mi Liangfu (芈良夫) | King Xuan | 370–340 | Brother of King Su (no heirs). |

| Mi Shang (芈商) | King Wei | 340–329 | Son of King Xuan. |

| Mi Guai (芈槐) | King Huai | 329–299 | Son of King Wei; captured by Qin. |

| Mi Heng (芈橫) | King Qingxiang | 299–263 | Brother of King Huai. |

| Mi Wan (芈完) | King Kaolie | 263–238 | Son of King Qingxiang. |

| Mi Yu (芈猷) | King You | 238–228 | Son of King Kaolie. |

| Mi Hao (芈昊) | King Ai | 228 | Brother of King You; brief rule, overthrown. |

| Mi Fuchu (芈負芻) | - | 228–223 | Brother of King Ai; final ruler before Qin annexation. |

(简).png/250px-战国形势图(前350年)(简).png)

(简).png)