Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

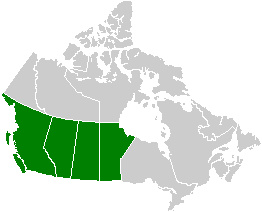

Western alienation

View on Wikipedia

Western alienation, in the context of Canadian politics, refers to the notion that the Western provinces—British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba—have been marginalized within Confederation, particularly compared to Central Canada, which consists of Canada's two most populous provinces, Ontario and Quebec. Expressions of western alienation frequently allege that Eastern Canada is politically over-represented and receives out-sized economic benefits at the expense of western Canadians.[1]

Western alienation has a long history within Canada, dating back to the nineteenth century. It has led to the establishment of many Western regional political parties at both the provincial and federal levels and from both the right and left sides of the political spectrum, although since the 1980s western alienation has been more closely associated with and espoused by conservative politicians. While such movements have tended to express a desire for a larger place for the west within Confederation, western alienation has at times resulted in calls for western separatism and independence. Given this long history, western alienation has had a profound impact on the development of Canadian politics.

According to a 2019 analysis by Global News, Western alienation is considered especially potent in Alberta and Saskatchewan politics.[2] However, alienation sentiments vary over time and place. For instance, a 2010 study published by the Canada West Foundation found that such sentiments had decreased across the region in the first decade of the twenty-first century.[3] More recently, a 2019 Ipsos poll found historically high levels of support for secession from Canada in both Alberta and Saskatchewan.[4]

Historical roots

[edit]Upon Confederation in 1867, the new Dominion of Canada consisted only of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. However, what was then known as the North-West—much of it officially Rupert's Land and owned by the Hudson's Bay Company—was already a significant factor in Canadian plans.[5][6] Among the country's founders, George Brown was particularly insistent that the North-West was the key to Canadian prosperity, offering resources, plentiful land for agricultural settlement, and the potential for a captive market for eastern manufacturers.[5][7] In 1869, HBC gave up its control of Rupert's Land, which became part of Canada in 1870 under the name North-West Territories.[8]

The National Policy

[edit]The first Canadian Prime Minister, John A. Macdonald, designed the National Policy to integrate the North-West Territories into Canada and to develop it economically as part of a Canadian economy. The key planks of the National Policy were the building of a trans-continental railway that would connect the east to British Columbia, help to settle and populate the west, and easily ship goods across the country (mostly grain and agricultural products grown in the Prairies, manufactured goods produced in central Canada); immigration to populate the Prairies with homesteaders; and tariffs to protect Canadian manufacturers.[9][10] The protectionist tariffs were an immediate issue in the North-West, as it effectively forced western farmers to purchase more expensive equipment from eastern Canadian manufacturers rather than less-expensive farm equipment from manufacturers in the United States, and it impacted prices for farm products—farmers of the North-West Territories therefore favoured free trade between Canada and the U.S.[11] This began a long battle between farmers on the prairies and the federal government and led to the establishment of farmers' organizations to help control grain shipping and marketing, and to agitate politically for free trade and economic protection for farmers as well.[12] Eventually, farmers entered the political sphere directly, forming United Farmers parties and the Progressive Party, both of which helped to lay a foundation for a national democratic-socialist party, Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF).[13][14]

Western provinces

[edit]The first province established in the North-West was Manitoba, and it entered Confederation under unusual circumstances. Negotiations were instigated at the behest of the Métis at Red River, who were wary of losing their land and rights as Canada encroached upon the territory. After the quelling of the Red River Resistance, Manitoba entered Confederation as a small province—it was jokingly derided as the "postage stamp province"—with limited rights, including a lack of control over its natural resources.[15]

British Columbia negotiated its own entry in 1871, but it was better positioned than the rest of the North-West and demanded and got a promise of the construction of a trans-continental railway.[16]

By the turn of the twentieth century, agitation for provincehood for the rest of the North-West increased as the land settlement grew. NWT premier Frederick Haultain proposed the creation of a large province between Manitoba and British Columbia, for which he favoured the name Buffalo.[17] However, some in the federal government, wary of creating too powerful of a province, opposed the creation of such a large province in the west.[18] The result was the 1905 establishment of the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, both of which were not given control of their resources, like Manitoba a generation earlier.[19] To protest this, Haultain led the Provincial Rights Party in Saskatchewan from 1905 until 1912.

While each of these provinces received federal grants as compensation for this lack of resource control, it remained a significant issue until 1930, when the Natural Resources Transfer Acts finally gave those provinces control of their own resources.[20]

The Great Depression

[edit]The Prairie provinces were by far the most impacted by the Great Depression. The economic depression was deepened on the Prairies by drought and dust bowl conditions, and all together farmers across the region were impoverished. Getting little in the way of relief from the federal government, the region was the slowest to recover from the Depression, which only passed with the arrival of the Second World War and the consequent revival in manufacturing, primarily benefiting business interests in Central Canada.[21] The depression caused the establishment of two parties that would dominate politics in Alberta and Saskatchewan for much of the next half-century- Social Credit and the CCF, both of which drew on the legacy of the United Farmer movements. The two new parties sought to transform economic and social conditions on the Prairies, albeit from different ideological positions, and their successes contributed to a tempering of western alienation for much of the middle of the twentieth century.[22] A related factor was an increased focus on resource development on the Prairies. This succeeded, filled provincial coffers and buoyed a recovery from the Depression.[23]

When John Diefenbaker became prime minister as the leader of a Progressive Conservative government in 1957, this also marked a shift in western relations. Diefenbaker, hailing from Saskatchewan, considered himself an unabashed champion of western interests, and his popularity helped to align conservatism at the federal level with the needs of Prairie farmers.[24]

Resource development

[edit]Before the Second World War, western alienation was principally rooted in a sense of being unequal in Confederation and held back in economic development—in a sense, the notion that the west was a colony of eastern Canada. This changed after the war, when the prairie provinces in particular became more prosperous, based largely on newfound resource wealth. Feelings of alienation returned in the 1970s, but by then were based principally on a sense of unjustified intrusion by the federal government into western economic interests. In part, this was an outcome of the expansion of the federal state in the postwar period, and in part this was due to the rising economic power of the prairie provinces. It had largely to do with debates over federalism versus decentralization in Canadian politics. The 1970s energy crises led to rapid increases in energy resource prices, which produced windfall profits in the energy-rich western provinces. The 1974 federal budget from Pierre Trudeau's Liberal government terminated the deduction of provincial natural resources royalties from federal tax. According to Roy Romanow—then Saskatchewan's attorney general—this move kicked off the "resource wars", a confrontation between Trudeau's federal government and the prairie provinces over the control of and revenues from natural resource extraction and energy production.[25]

Following an increase in the world price of oil between 1979 and 1980, Trudeau's government introduced the National Energy Program (NEP), which was designed to increase Canadian ownership in the oil industry, increase Canada's oil self-sufficiency, and redistribute the wealth generated by oil production with a greater share going to the federal government.[26] While the program was meant to mitigate the effect of higher gas prices in eastern Canada, it was extremely unpopular in the west due to the perception that the federal government was implementing unfair revenue sharing.[27] In response, a quote from future Alberta Premier Ralph Klein—then the mayor of Calgary—featured prominently on bumper stickers in that province: "Let the eastern bastards freeze in the dark".[28] The program was ultimately repealed in 1985.

Resource rights were prominent in negotiations of the Patriation of the Canadian Constitution in the early 1980s. Alberta and Saskatchewan premiers Peter Lougheed and Allan Blakeney negotiated to ensure that provincial resource rights were enshrined in Section 92A of the Constitution.[29]

The Reform Party

[edit]Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservatives replaced the Liberals with an historic majority in the 1984 election. However, Mulroney was seen as similarly neglectful of western Canada, which led to the establishment of the conservative Reform Party in 1987.[30] Led by Preston Manning—son of former Alberta Social Credit premier Ernest Manning—Reform campaigned on the slogan "The West Wants In". Despite controversy over the party's social conservatism, it surged to third party status in 1993, winning 52 seats—all but one of them in Western Canada—in the fall election while the PCs were reduced to just 2. In the 1997 election, Reform became the Official Opposition. In 2000, Reform rebranded as the Canadian Alliance in an attempt to appeal to voters beyond Western Canada; in 2003, the party merged with the PCs to form the Conservative Party of Canada, the power base of which has since resided in the west.[31]

Contemporary western alienation

[edit]

The twenty-first century has seen a resurgence of western alienation sentiments, which coincided again with the boom and bust of commodity prices.[32] Paul Martin stated that addressing western alienation was one of his two priorities when he became prime minister in 2003.[33] In 2007, he said he had learned that the phenomenon ebbs and flows, and by the end of that decade such sentiments were reported to have decreased.[3][33] However, particularly since the 2015 election of a Liberal federal government under the leadership of Justin Trudeau—the son of Pierre Trudeau—western alienation has reached heights not seen since the 1980s.[34][35] This has largely to do with perceptions of federal overreach by a governing party that has frequently been shut out of much of the Prairies. In particular, federal environmental policy and efforts at addressing climate change, such as the Pan-Canadian Framework, have been at the core of contemporary western alienation, stoking fears of a forced economic downturn for key resource industries. However, this resurgence of western alienation also coincided with a major downturn in commodity prices after 2014.[36]

Governments in both Alberta and Saskatchewan have characterized federal environmental policy as an attack on their respective resource industries, and therefore as a threat to their provinces' economic stability. The Saskatchewan Party, especially under the leadership of Scott Moe since 2018, and since its formation in 2017 Alberta's United Conservative Party—currently under the leadership of Danielle Smith—have positioned themselves in opposition to Ottawa, and sought greater autonomy within Canada. At the same time, polling has consistently suggested that Alberta and Saskatchewan residents perceive the federal government as harmful to their province's interests.[2][4][35] Moreover, residents in British Columbia and Manitoba have also indicated a sense of rising resentment towards Ottawa, and residents in all four western provinces indicated that they would support a new "Western Canada Party" at the federal level to advocate for the region's interests.[37]

Also at question is the degree to which westerners identify more with their region or province than with the country. 2018 polling suggested that 76% of western Canadians felt a sense of "unique western Canadian identity", the same percentage that said so in 2001.[38] Governments have at times contributed to such sentiments. For example, Scott Moe in 2021 called for recognition of Saskatchewan as a "nation within a nation"—drawing on terminology frequently employed by Quebec nationalists—and argued that the province has its own "cultural identity".[39] In 2023, Saskatchewan made it mandatory for schools in the province to fly the provincial flag, which the government indicated was meant to increase pride in provincial identity.[40]

Legal and policy challenges

[edit]The federal effort to institute a carbon tax across the country has been a significant point of contention. Saskatchewan—which was later joined by Alberta along with Ontario—challenged the constitutionality of the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act in court. The challenge was first launched in April 2018, and in March 2021 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the Act is constitutional.[41] The western provinces found some success in their constitutional challenge against federal environmental impact assessment legislation, as the Supreme Court ruled in October 2023 that portions of the 2019 Impact Assessment Act dealing with "designated projects" outside of federal jurisdiction were unconstitutional.[42] An amended Impact Assessment Act received royal assent in June 2024.[43]

In 2022, both Alberta and Saskatchewan passed new legislation to affirm their control over natural resources and to try and mitigate the encroachment of federal power. The Alberta Sovereignty Act and the Saskatchewan First Act were both introduced in November 2022.[44][45]

Alberta and Saskatchewan have made other efforts to distance themselves from Ottawa. Both have frequently criticized the equalization payment scheme as unfair. In his call for "A New Deal with Canada", Moe has signaled a desire for more control over taxation and immigration, and Saskatchewan has introduced plans to create a provincial police force.[46][47] Smith has opened discussions about Alberta withdrawing from the Canada Pension Plan and starting its own.[48]

Convoy protests

[edit]Since 2019, a number of popular protests have organized convoys to Ottawa to take demands directly to the federal government, something that has a long tradition in western Canada dating back to the early twentieth century, including the attempted On-to-Ottawa Trek during the Great Depression. In particular, large convoy protests in 2018 and 2022 have received international attention.[36][49][50] The first of these convoys was organized by the "yellow vests movement", which drew inspiration from the 2018 French yellow vests protests. The Canadian protest demanded, among other things, the elimination of the federal carbon tax. The second was the self-styled "freedom convoy", which purported to be focused on protesting COVID-19 vaccine mandates, but shared many of the same organizers and resources as the 2018 protest. In both cases, the extent to which the convoys were supported by western Canadians was a subject of debate; for example, a 2022 study suggested that fewer than 20% of Albertans thought positively of the convoy protest.[51] Moreover, several studies have indicated that these protests included a high degree of far-right political elements, including xenophobic and conspiratorial elements.[52][53][54]

Western separatism

[edit]Particularly since the 1970s, when the resource-based economies of Alberta and Saskatchewan began to see rapid growth, the idea of separatism and independence for western provinces—on their own or in some combination together—has at times gained political traction and led to the creation of new movements and parties working towards that end. Such sentiment did not arise in a vacuum, with agitation for Quebec sovereignty reaching new heights in the 1970s. The extent to which agitation for western sovereignty has merely been a "bargaining tool" for the west, as former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau characterized it in 1980, has been debated, and western Premiers, including Peter Lougheed, have tended to downplay any push for secession.[55] Parties advocating for western secession have tended to fare poorly at the polls.

1980s

[edit]

While movements like the Reform Party stated that they were dedicated to realizing a bigger role for the west within Canada, other movements, like the Western Canada Concept, founded in 1980, argued that the west would be better off carving out its own nation, and was politically and economically capable of doing so.[56] Although envisioned as a federal movement, Western Canada Concept never ran candidates in a federal election. However, it did field provincial branches in each of the western provinces. It found its biggest success in Alberta, where Gordon Kesler won a 1982 by-election under the WCC banner; in that year's general election, the party was one candidate short of a full slate and earned 12% of the vote, although none of its candidates were elected.[57] During Saskatchewan's 20th Legislature, two sitting MLAs—Bill Sveinson and Lloyd Hampton—took up the WCC banner. However, the party failed to have any candidates elected in the 1986 election.

The short-lived Unionest Party in Saskatchewan offered another separatist option in that province. Former Progressive Conservative leader Dick Collver founded the party in 1980, and advocated for a secession of western provinces and a subsequent union with the United States—Unionest was a contraction of "best" and "union". This was seen as "traitorous" by some, and somewhat ironic given that one factor in Canada's acquisition of the west was to avoid its annexation by the US.[58]

Other such movements that arose to advocate for secession include the Western Independence Party, which fielded candidates in federal and provincial elections from 1988 into the twenty-first century, and the Western Block Party.[59]

Wexit (2019–)

[edit]Separatist sentiment began to re-emerge ahead of the 2019 federal election, with one study indicating record levels of separatist sentiment in Alberta and Saskatchewan.[18][34] In the wake of the 2019 election—which saw the governing Liberal Party shut out from both Alberta and Saskatchewan—the "Wexit" movement consolidated this new wave of separatist sentiment.[36] A play on the British "Brexit" movement, Wexit established federal and provincial branches to advocate for western secession, and adopted a reversed version of Preston Manning's slogan: "The West Wants Out".[60] In 2020, Wexit Canada rebranded as the Maverick Party;[61] Wexit Alberta merged with the Freedom Conservative Party to form the Wildrose Independence Party;[62] and Wexit Saskatchewan rebranded as the Buffalo Party.[63] Wexit BC was de-registered in 2022.[64]

In the 2020 Saskatchewan provincial election, the Buffalo Party ran just 17 candidates but received 2.6% of the popular vote, more than any other third party, and finished second in a handful of rural ridings.[65] The result prompted Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe to state that his Saskatchewan Party—which handily won a majority government—"share your frustrations", and to call for more "independence" from Ottawa, although he downplayed talk of secession.[66] Ahead of the 2021 federal election, the Maverick Party stated that it was trying to emulate the model laid out by the Bloc Québécois.[67] However, the party failed to gain traction in the election, earning just over 1% of the vote in each of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Then-interim leader Jay Hill acknowledged after the election that focusing on separatism created "a certain degree of discomfort with most westerners who aren’t prepared at this point to go that far."[68] Although Maverick did not officially endorse the 2022 convoy protest that occupied Ottawa, many of its members supported it and one of the party's secretaries, Tamara Lich, was a key convoy organizer.[69] The party ultimately lost momentum and was de-registered in 2025.[70] There are also signs of the movement losing traction in Saskatchewan. After its surprising 2020 performance, the Buffalo Party fell to sixth place in the 2024 provincial election, earning less than 1% of the popular vote.[71]

In the wake of the 2025 Canadian federal election, which resulted in the Liberal Party being re-elected to a fourth term, this time under the leadership of Mark Carney, United Conservative Party members reignited agitation for Alberta separatism.[72] The day after the election, Danielle Smith introduced legislative changes to make it easier for citizens to trigger a referendum.[73]

Impact of Quebec separatism

[edit]It was revealed in 2014 that Roy Romanow's New Democratic Party government in Saskatchewan held secret meetings to discuss contingencies for the event of a successful secession vote in the 1995 Quebec referendum, including the possibility of following suit and potentially courting annexation by the United States. Romanow stated that Allan Blakeney had held similar discussions ahead of the 1980 Quebec referendum. He further explained that, in his view, secession for Saskatchewan "would not make sense economically and socially".[74]

Responses to western alienation

[edit]Federal government

[edit]In the 1980s, Pierre Trudeau called talk of western alienation and separatism a "bargaining tool" for the west, and urged the west to find ways to get more representation in the federal government.[55] For his part, given the lack of Liberal representation in the west—his party won only two seats west of Ontario, both of them in Manitoba—Trudeau took the uncommon step of appointing western senators to his cabinet.[75][76]

Amidst criticism that the federal government was inhibiting pipeline development, Justin Trudeau's Liberals purchased the Trans Mountain pipeline in 2018 to try and help ensure the completion of its expansion project, which has before and since been mired in financial uncertainty.[77][78]

First Nations

[edit]First Nations leaders have often asserted that they have been forgotten in discussions of western alienation. Given that First Nations in Canada have direct relationships with the federal government, and the large number of First Nations in western Canada, such assertions complicate those discussions. This is particularly true in British Columbia, where a large number of First Nations have never entered into treaty agreements with the federal government.[79]

In recent years, Indigenous leaders have pushed back against talk of western alienation, particularly talk of western separatism. In 2019, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde said that First Nations consent would be required for any secession, given that "provincial boundaries came after treaty territories", further adding that western leaders "have to be careful when you go down that road of Western alienation... We have inherent rights... and those are international agreements with the Crown."[80] Saskatoon Tribal Council Chief Marc Arcand added that any western province "does not have the authority to decide if they want to separate".[80] First Nations chiefs from Treaty 8 territory also released a statement in 2019, declaring that they were "strongly opposed to the idea of separation from Canada."[81] In 2025, two First Nations chiefs in Alberta again pushed back against separatist rhetoric, addressing a letter to Danielle Smith, urging the Premier to respect Treaty rights and stop stoking separatist sentiments.[82] First Nations leaders have been similarly vocal in their opposition to the 2022 Alberta Sovereignty and Saskatchewan First Acts, arguing that they infringe on treaty rights and circumvent their relationship with the Crown. Both Acts were drafted without consultation with Indigenous communities.[83]

Political parties

[edit]The following is a list of federal and provincial political parties that were founded in response to western alienation, to advance western interests within Canada, or to promote western independence. Some such parties, like the CCF and Reform, have merged with other entities to become truly national parties.

| Party name | Founded | Level | Political position | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial Rights Party | 1905 | Provincial (SK) | Right-wing | Advocated for equal rights for the province within Confederation. Became the provincial Conservative Party in 1912. | |

| United Farmers | 1919 | Provincial | Left-wing | Agrarian parties that formed government in Alberta (1921) and Manitoba (1922); also formed government in Ontario (1919). Parties played roles in forming the Progressive Party and CCF. | |

| Progressive Party | 1920 | Federal/provincial | Left-wing | Outgrowth of the agrarian United Farmers movement. Won the second most seats in the 1921 election, but declined to form the Official Opposition | |

| Co-operative Commonwealth Federation | 1932 | Federal/provincial | Left-wing | Democratic socialist party formed out of a union of labour and agrarian interests. Formed government in Saskatchewan in 1944. Merged with Canadian Labour Congress in 1961 to form the NDP. | |

| Social Credit Party | 1935 | Federal/provincial | Right-wing | A mix of social credit monetary reform theory and Christian right social conservatism. Formed government in Alberta in 1935. | |

| Western Canada Concept | 1980 | Federal/provincial | Right-wing | Separatist party. | |

| Unionest Party | 1980 | Provincial (SK) | Right-wing | Advocated for Western Canada to join the United States. | |

| Alberta Party | 1985 | Provincial (AB) | Centrist | Originally a separatist party; especially since 2009, seen as centrist and Alberta-focused. | |

| Reform Party | 1987 | Federal | Right-wing | Populist party with Christian right influences. In 2000, became Canadian Alliance, and in 2003 merged with the Progressive Conservatives to form the modern Conservative Party. | |

| Western Independence Party | 1988 | Federal/provincial | Right-wing | Separatist party. | |

| Saskatchewan Party | 1997 | Provincial (SK) | Right-wing | Although initially focused on Saskatchewan politics, especially since 2015 seen as increasingly focused on provincial independence. | |

| Alberta First Party | 1999 | Provincial (AB) | Right-wing | Separatist party. | |

| Western Block Party | 2005 | Federal | Right-wing | Separatist party. | |

| Wildrose Party | 2007 | Provincial (AB) | Right-wing | Autonomist party. | |

| Independence Party | 2017 | Provincial (AB) | Right-wing | Separatist party. In 2018, became the Freedom Conservative Party. | |

| Freedom Conservative Party | 2018 | Provincial (AB) | Right-wing | Separatist party. In 2018, merged into the Wildrose Independence Party. | |

| Maverick Party | 2020 | Federal | Right-wing | Originally Wexit Canada. Separatist party. | |

| Buffalo Party | 2020 | Provincial (SK) | Right-wing | Originally Wexit Saskatchewan. Separatist party. | |

| Wildrose Independence Party | 2020 | Provincial (AB) | Right-wing | Originally Wexit Alberta and the Freedom Conservative Party. Separatist party. | |

| Republican Party | 2022 | Provincial (AB) | Right-wing | Originally Buffalo Party of Alberta. Pro-American party. | |

| Wildrose Loyalty Coalition | 2023 | Provincial (AB) | Right-wing | Separatist party. | |

See also

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Canada |

|---|

References

[edit]- ^ Berdahl, Loleen (June 9, 2021). "The past, present, and future of western alienation". Policy Options. Institute for Research on Public Policy. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Sorensen, Eric (October 25, 2019). "Analysis: Western alienation is very real in Alberta and Saskatchewan". Global News. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Berdahl, Loleen (2010). Whither Western Alienation? Shifting Patterns of Western Canadian Discontent with the Federal Government. Calgary: Canada West Foundation. p. 1. ISBN 9781897423707.

- ^ a b Shah, Maryam (November 5, 2019). "Separatist sentiment in Alberta, Saskatchewan at 'historic' highs: Ipsos poll". Global News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Belshaw, John Douglas (2020). "Canada Captures The West: 1867–70". Canadian History: Post-Confederation (2nd ed.). Victoria, British Columbia: BCcampus. ISBN 9781774200650.

- ^ Conway, John F. (2014). The Rise of the New West: The History of a Region in Confederation. Toronto: James Lorimer & Co. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9781459406247.

- ^ Ajzenstat, Janet; Romney, Paul; Gentles, Ian; Gairdner, William D., eds. (2003). Canada's founding debates. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 133–137. ISBN 9780802086075.

- ^ Conrad, Margaret (2012). A Concise History of Canada. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–155. ISBN 9780521744430.

- ^ Conrad. Concise History of Canada. pp. 158–159.

- ^ "Building a Nation". Canada: A People's History. CBC Learning. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ Brown, Robert Craig. "National Policy". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 29, 2012. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ Conway. Rise of the New West. pp. 42–47.

- ^ Conway. Rise of the New West. pp. 61–63.

- ^ Friesen, Gerald (1984). The Canadian Prairies: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 374–381. ISBN 0802025137.

- ^ Goldsborough, Gordon (Summer 2015). "The Postage Stamp Province". Manitoba History (78). Manitoba Historical Society.

- ^ Belshaw (2020). "British Columbia and the Terms of Union". Canadian History.

- ^ Waiser, Bill (2005). Saskatchewan: A New History. Calgary: Fifth House. pp. 5–7. ISBN 9781894856492.

- ^ a b Eneas, Bryan (September 20, 2019). "Disenfranchisement and disappointment: Idea of western Canadian separation has deep roots in Prairies". CBC News. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Payne, Michael, ed. (October 18, 2013). "Redrawing the West: The Politics of Provincehood in 1905". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Editorial. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Sommers, Javed (June 19, 2023). "Legislating Broken Promises: Canada's Natural Resources Transfer Agreement Today". NiCHE | Network in Canadian History & Environment. Archived from the original on June 19, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Belshaw (2020). "The Great Depression". Canadian History.

- ^ "Striking Back". Canada: A People's History. CBC Learning. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ Owram, Doug (2020). "The New Economy". In Belshaw, JD (ed.). Canadian History.

- ^ Martin, Joseph (June 11, 2007). "Let's be honest about 'Honest John'". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Back to Blakeney: Revitalizing the Democratic State. McGrane, David,, Romanow, Roy J.,, Whyte, John D.,, Isinger, Russell, 1965-. Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. August 24, 2019. ISBN 978-0-88977-641-8. OCLC 1090178443.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bregha, Francois. "National Energy Program". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ "Canadian Energy Overview 2010 – Energy Briefing Note". National Energy Board. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ Martin, Sandra (March 29, 2013). "Ralph Klein, 70: The man who ruled Alberta". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Romanow, Roy (2019). "Principled Pragmatism: Allan Blakeney and Saskatchewan's 'Resource Wars'". In Isinger, Russel; Whyte, John D.; Romanow, Roy; McGrane, David (eds.). Back to Blakeney: Revitalizing the Democratic State. Regina: University of Regina Press. pp. 6–12. ISBN 9780889776821.

- ^ Nossal, Kim Richard (June 1, 2003). "The Mulroney Years: Transformation and Tumult". Policy Options. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ Grenier, Eric (February 10, 2021). "Why Conservatives can't turn their backs on their western base". CBC News. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "Alienating the west". The Economist. Special report. The Canadian Press. December 1, 2005. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ a b MacGregor, Roy (July 28, 2007). "Paul Martin's new mission". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Soloducha, Alex (May 10, 2019). "Survey suggests Sask. residents want Western Canada to separate". CBC News. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Anderson, Drew (October 28, 2019). "The anger is real, but is western separatism?". CBC News. Archived from the original on October 31, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c Levinson-King, Robin (October 11, 2019). "Wexit: Why some Albertans want to separate from Canada". BBC News. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "Decades after Reform's rise, voters open to a new 'Western Canada Party'". Angus Reid Institute. February 5, 2019. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Vomiero, Jessica (October 8, 2018). "Western Canadians still feel more connected to their province than to country as a whole: Ipsos". Global News. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ Hunter, Adam (November 9, 2021). "Premier Moe wants Saskatchewan to be a 'nation within a nation' by increasing autonomy". CBC News. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "Saskatchewan flag legally required to be flown at schools as part of parental rights' bill". CBC News. October 22, 2023. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Tasker, John Paul (March 25, 2021). "Supreme Court rules Ottawa's carbon tax is constitutional". CBC News. Archived from the original on March 25, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Gowling, Jordan (October 13, 2023). "Supreme Court rules against federal environmental impact assessment law". CTV News. Archived from the original on October 14, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "Amended Impact Assessment Act now in force". Government of Canada. June 21, 2024. Archived from the original on June 21, 2024. Retrieved May 11, 2025.

- ^ Bennett, Dean (December 8, 2022). "Alberta passes Sovereignty Act, but first strips out sweeping powers for cabinet". CBC News. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on December 11, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Bamford, Allison; Prisciak, David (November 1, 2022). "'Saskatchewan First Act' aims to assert constitutional jurisdiction: province". CTV News. Archived from the original on November 10, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Wiens, Colton; Solomon, Michaela (October 22, 2019). "'New deal with Canada': Premier Scott Moe calls on Prime Minister to support Sask". CTV News. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Simes, Jeremy (August 16, 2023). "As Sask. forms new police service; critics question lack of oversight". CTV News. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Heydari, Anis (November 2, 2023). "What is the CPP anyway? And why is Alberta leaving it different from Quebec?". CBC News. Archived from the original on November 3, 2023. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Newton, Paula (February 11, 2022). "They are protesting Covid restrictions and support is growing. This is what could happen in the Canada protests next". CNN. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Murphy, Jessica (January 29, 2022). "Freedom Convoy: Why Canadian truckers are protesting in Ottawa". BBC News. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Climenhaga, David (October 17, 2022). "Think the Convoy Had Big Support in Alberta? Hardly". The Tyee. Archived from the original on October 25, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Mosleh, Omar (January 4, 2019). "Canada's yellow vest movement looks like it's here to stay — but what is it really about?". StarMetro Edmonton. Archived from the original on November 4, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2023 – via Toronto Star.

- ^ "The 'Freedom Convoy' is nothing but a vehicle for the Far Right". Canadian Anti-Hate Network. January 27, 2022. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ MacDonald, Fiona (February 16, 2022). "The 'freedom convoy' protesters are a textbook case of 'aggrieved entitlement'". The Conversation. Archived from the original on February 19, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ a b "In the '70s and '80s, some wanted Alberta to separate from Canada". CBC Archives. October 24, 2019. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "What is the Western Canada Concept?". Western Canada Concept. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "Alberta separatism was a thing in the early 1980s". CBC Archives. April 15, 2019. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Waiser. Saskatchewan. p. 428.

- ^ Edmiston, Jake (January 28, 2014). "Dream of 'free and independent Western Canada' ends as separatist party officially deregistered". National Post. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Bartko, Karen (November 5, 2019). "The West Wants Out: Alberta separatist group Wexit Canada seeking federal political party status". Global News. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Dryden, Joel (September 17, 2020). "Seeking broader appeal, separatist Wexit Canada party changes its name to the Maverick Party". CBC News. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "Wexit Alberta and Freedom Conservative Party vote to merge as Wildrose Independence Party of Alberta". CBC News. June 30, 2020. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Zinchuk, Brian (July 26, 2020). "Provincial separatist party rebrands, appoints new interim leader". Estevan Mercury. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2025 – via Humboldt Journal.

- ^ "DEREGISTRATIONS". The British Columbia Gazette. 162 (28). Victoria, British Columbia: Queen's Printer. July 14, 2022. Archived from the original on October 21, 2023. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Kliem, Theresa (October 26, 2020). "Buffalo Party runs fraction of candidates, yet outdraws Greens in preliminary election count". CBC News. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ White-Crummey, Arthur (October 27, 2020). "Scott Moe walks 'fine line' by backing independence, not separation". Regina Leader-Post. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Graveland, Bill (September 12, 2021). "Maverick Party looks to Bloc Québécois as inspiration to ensure western interests". CBC News. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Graveland, Bill (October 2, 2021). "Maverick Party planning to up its game after poor election results". Global news. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Climenhaga, David (January 26, 2022). "A BC Ex-MP, Western Separatists and that Truck Protest". The Tyee. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ Kurjata, Andrew (March 24, 2025). "Maverick Party, which pushed for Wexit and western autonomy, will not run in federal election". CBC News. Archived from the original on March 25, 2025. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ Bykhovskaia, Anastasiia; Willberg, David (October 29, 2024). "Buffalo Party leader, others react to Estevan-Big Muddy results". Sask Today. Archived from the original on November 11, 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Markusoff, Jason (April 16, 2025). "Alberta separatists getting organized — a unity challenge for Canada and Danielle Smith's party". CBC News. Archived from the original on April 16, 2025. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ Bellefontaine, Michelle (April 29, 2025). "Alberta overhauls election laws to allow corporate donations, change referendum thresholds". CBC News. Archived from the original on April 30, 2025. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ Warren, Jeremy (August 26, 2014). "Secret Romanow group mulled secession". The StarPhoenix. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "How Pierre Trudeau ensured western cabinet representation in 1980". CBC Archives. February 27, 2020. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Lang, Eugene (November 1, 2019). "The Trudeaus and western alienation". Policy Options. Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ MacCharles, Tonda; Campion-Smith, Bruce; Ballingall, Alex (May 29, 2018). "Liberal government to buy Trans Mountain pipeline project, seek new investors". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on November 5, 2023. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Thurton, David (May 13, 2023). "The overbudget Trans Mountain pipeline project is carrying $23B in debt — and needs to borrow more". CBC News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2023. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ McIntosh, Emma (January 24, 2020). "What we mean when we say Indigenous land is 'unceded'". Canada's National Observer. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Barrera, Jorge (October 30, 2019). "Western separatism would have to face treaty nations, say First Nations leaders". CBC News. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Heidenreich, Phil (November 6, 2019). "Treaty 8 chiefs call Wexit a 'bad idea' as support for separating from Canada grows in Alberta". Global News. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "Indigenous chiefs accuse Alberta Premier Smith of stoking separatism talk". Edmonton Journal. The Canadian Press. May 1, 2025. Archived from the original on May 1, 2025. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ Ghania, Yasmine; Kliem, Theresa (December 7, 2022). "First Nations demand withdrawal of proposed Alberta Sovereignty, Saskatchewan First acts". CBC News. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Berdahl, Loleen (May 27, 2021). "The Persistence of Western Alienation". Institute for Research on Public Policy. Inaugural Essay Series. Centre of Excellence on the Canadian Federation. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- Berdahl, Loleen. "Western Alienation". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- Braid, Don (1990). Breakup: why the West feels left out of Canada. Toronto: Key Porter Books. ISBN 978-1-55013-256-4.

- Janigan, Mary (2013). Let the Eastern Bastards Freeze in the Dark: The West Versus the Rest Since Confederation. Toronto: Knopf Canada. ISBN 9780307400628.

- Melnyk, George (1993). Beyond alienation: political essays on the West. Calgary: Detselig Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-55059-060-9.

- Young, Lisa; Archer, Keith, eds. (2002). Regionalism and party politics in Canada. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-541599-5.

Western alienation

View on GrokipediaWestern alienation denotes the persistent sentiment in Canada's western provinces—primarily Alberta, Saskatchewan, and to varying degrees Manitoba and British Columbia—of political marginalization and economic disadvantage imposed by a federal system oriented toward the interests of Central Canada, encompassing Ontario and Quebec.[1][2] This perception arises from structural imbalances in federal representation, where the West's parliamentary influence remains limited despite its economic contributions, compounded by policies that redirect resource revenues eastward without equitable reciprocity.[3] Historically rooted in the post-Confederation era, western alienation intensified under the National Policy of 1879, which imposed protective tariffs benefiting Eastern manufacturers while burdening Prairie farmers with higher costs for imported goods and restricted market access.[4] Subsequent flashpoints, such as the 1980 National Energy Program, exemplified federal intervention in provincial resource sectors, aiming to nationalize oil and gas revenues and impose price controls that disproportionately harmed Alberta's economy, evoking widespread resentment over lost sovereignty and fiscal autonomy.[5] Central to these grievances is the federal equalization program, under which high-revenue provinces like Alberta—never a recipient since the program's inception in 1957—effectively subsidize transfers to lower-fiscal-capacity regions through general tax revenues, fostering perceptions of systemic wealth extraction without corresponding infrastructure or policy concessions for contributors.[6][7] Defining characteristics include advocacy for institutional reforms, such as an elected Senate to amplify regional voices, and the emergence of protest movements and parties like the Reform Party, which channeled alienation into demands for decentralization and fiscal federalism.[2] In contemporary contexts, regulatory hurdles to energy projects and carbon pricing have sustained these tensions, underscoring causal links between federal centralization and regional discontent.[8][3]

Definition and Core Concepts

Scope and Regional Boundaries

Western alienation refers to the persistent sense of political, economic, and cultural disconnection experienced by residents of Canada's four westernmost provinces: British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. This regional discontent stems from perceptions that federal policies disproportionately benefit Central Canada—Ontario and Quebec—at the expense of Western interests, particularly in resource development and fiscal transfers.[2] Geographically, the scope is bounded by Manitoba's eastern edge, adjacent to Ontario, and extends westward to the Pacific coast of British Columbia, encompassing approximately 2.9 million square kilometers or about 29% of Canada's land area. While the three Prairie provinces—Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta—form the historical core due to shared agrarian and resource-based economies, British Columbia's inclusion reflects common grievances over federal overreach in areas like energy pipelines and environmental regulations, despite its more diverse urban and coastal profile. The sentiment is less pronounced in the northern territories (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), which face distinct Indigenous and resource challenges but lack the same provincial autonomy and population scale.[9][10] Regional boundaries are not rigidly fixed, as alienation's intensity fluctuates; for instance, post-2015 federal policies intensified feelings in Alberta and Saskatchewan, narrowing focus to these oil-dependent provinces amid pipeline delays and carbon taxes, while Manitoba and British Columbia exhibit more variable alignment with national politics. Surveys indicate that in 2019, over 50% of Albertans and Saskatchewan residents expressed strong alienation, compared to lower rates elsewhere in the West. This variability underscores that Western alienation operates as a fluid political identity rather than a uniform geographic bloc, often amplified during federal elections where Western seats yield disproportionate policy influence relative to population.[10][3]Fundamental Grievances and Causal Factors

Western alienation arises from a perception of systemic economic disadvantage, wherein resource-producing provinces in Western Canada, particularly Alberta, generate substantial federal revenues from oil, gas, and minerals but experience net fiscal outflows that subsidize other regions. Alberta, for example, has not received equalization payments since the program's start in 1957 and contributed an estimated $3.3 billion to the $24 billion in total equalization entitlements in 2023, representing a per capita drain exceeding $700 annually when accounting for broader federal transfers.[11][12] This dynamic stems from the federal tax system's aggregation of resource royalties and corporate taxes, which flow eastward to fund programs like healthcare and infrastructure in recipient provinces such as Quebec and the Maritimes, fostering resentment over unequal burden-sharing in a federation where Western per capita GDP significantly outpaces the national average—Alberta's at $78,000 in 2023 versus Canada's $59,000.[11] Federal energy policies have historically amplified these economic grievances by prioritizing national objectives over regional interests, as exemplified by the National Energy Program (NEP) implemented on October 28, 1980, which imposed federal taxes on petroleum revenues, mandated Canadian ownership quotas, and controlled domestic prices to benefit Eastern consumers. The NEP triggered an exodus of foreign investment from Alberta, with over $100 billion in capital flight by 1982, job losses exceeding 100,000 in the energy sector, and a provincial GDP contraction of 5.5% in 1982 alone, events widely interpreted as deliberate extraction of Western wealth to offset Eastern manufacturing declines amid global oil price volatility.[13][14] Subsequent policies, including regulatory delays and vetoes on pipelines like Energy East (cancelled in 2017) and Northern Gateway (denied in 2016), have restricted market diversification, leaving Alberta's oil sands output—peaking at 3.4 million barrels per day in 2019—vulnerable to Western Canadian Select discounts averaging $15–20 per barrel below Brent crude from 2018–2023 due to limited export infrastructure.[3] Politically, underrepresentation exacerbates alienation, as Western provinces hold only 106 of 338 House of Commons seats despite comprising 30% of Canada's population in 2021, a disparity rooted in the electoral quotient formula that caps Western growth relative to slower-growing Atlantic provinces.[15] The unelected Senate's equal provincial allocation fails to counterbalance this, as its ineffectiveness—evident in stalled Western-initiated bills—reinforces perceptions of Central Canadian dominance, where Ontario and Quebec control 198 seats and shape policies favoring urban and manufacturing priorities over rural resource economies. Causal factors include Canada's quasi-federal structure, which centralizes fiscal and regulatory power in Ottawa, geographic isolation breeding cultural divergence (e.g., Western emphasis on self-reliance versus Eastern reliance on transfers), and resource curse dynamics amplifying vulnerability to federal interventions that ignore local comparative advantages.[3][16]Historical Development

National Policy and Early Exploitation (1867–1910s)

The acquisition of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870 for £300,000 (£300,000 equivalent to approximately $1.5 million CAD at the time) marked the federal government's initial thrust into prairie expansion following Confederation in 1867.[17] This purchase, ratified by the Rupert's Land Act 1868 and Deed of Surrender, transferred roughly 1.5 million square miles to Canadian control, but implementation involved surveys and treaties that prioritized settler interests over Indigenous land rights, setting a precedent for centralized resource oversight from Ottawa. The Manitoba Act, passed on May 12, 1870, then carved out the small province of Manitoba—initially just 18 townships in area—from this territory, admitting it as Canada's fifth province on July 15, 1870, amid the Red River Resistance led by Louis Riel, whose provisional government's demands for larger boundaries and protections were partially unmet, fueling early regional tensions.[18] British Columbia's entry into Confederation on July 20, 1871, further exemplified federal inducements to Western integration, with the Terms of Union stipulating a cash subsidy, responsible government, and crucially, completion of a transcontinental railway within ten years to link the Pacific coast eastward.[19] Delayed beyond the 1881 deadline due to fiscal constraints and engineering challenges, this commitment highlighted the West's peripheral status: provinces joined on conditions favoring national connectivity over local autonomy, with British Columbia receiving 400,000 acres annually for public works but reliant on Ottawa's timeline and financing. Immigration policies complemented these efforts, drawing over 1.5 million settlers to the prairies by 1911, yet federal control of land sales and surveys often directed revenues eastward, reinforcing perceptions of the West as an undeveloped frontier for Central Canadian benefit. John A. Macdonald's National Policy, unveiled in the 1879 budget after the Conservative victory in 1878, formalized this dynamic through three interlocking elements: protective tariffs averaging 17.5–20% on manufactured goods (rising the weighted average from 14% pre-policy to 21%), transcontinental railway construction, and aggressive Western settlement via immigration.[20][21] For prairie farmers, who exported grain and livestock tariff-free but imported binders, plows, and other machinery at elevated costs—often 30–50% higher on key items—the policy acted as a regressive tax, transferring wealth to protected factories in Ontario and Quebec without insulating Western agriculture from global price volatility. Empirical data from the era show wheat prices fluctuating between $0.70–$1.00 per bushel in Winnipeg markets (1880–1900), while tariff-induced input costs eroded margins, prompting farmers' associations like the Manitoba and North-West Farmers' Union (founded 1883) to decry the system as colonial extraction.[20] The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), incorporated in 1881 and spanning 3,000 miles upon completion in November 1885, epitomized policy-driven exploitation, subsidized by $25 million in cash and 25 million acres of fertile land grants—equivalent to one-eighth of Canada's arable territory at the time.[22] These incentives enabled construction amid labor shortages (including 15,000 Chinese workers paid $1.00 daily), but the CPR's legal monopoly until the early 1900s allowed freight rates as high as $0.20–$0.30 per hundredweight on grain from Regina to Montreal, capturing up to 40% of export values and directing surpluses to bondholders and Eastern ports rather than reinvesting locally. By the 1910s, as wheat production surged to 200 million bushels annually in the prairies, these rates and tariffs had entrenched a staple-export model where Western output financed national infrastructure—such as the $50 million+ in total railway subsidies—while yielding minimal political or fiscal reciprocity, crystallizing the causal roots of alienation through demonstrable economic subordination.[20]Settlement Era and Great Depression (1920s–1930s)

The settlement of the Prairie provinces accelerated in the 1920s following the post-World War I wheat boom, with over 500,000 immigrants arriving in Western Canada between 1920 and 1930, primarily to farm the region's vast grasslands.[23] This era saw initial prosperity driven by high global demand for Canadian wheat, enabling rapid expansion of agricultural infrastructure and rural communities in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.[24] However, underlying structural issues emerged, as the region's export-oriented grain economy clashed with federal policies inherited from the National Policy, including high protective tariffs averaging 20-30% on manufactured imports, which inflated costs for prairie farmers needing affordable machinery and goods while shielding Ontario and Quebec industries.[20] Freight rate structures exacerbated these tensions, with the Crow's Nest Pass Agreement of 1897 providing subsidized eastbound grain rates but imposing higher westbound charges for imports, effectively subsidizing Central Canadian consumers at the expense of prairie producers.[25] Prairie farmers and organizations like the Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association repeatedly lobbied for tariff reductions and freer trade to access larger markets, arguing that Ottawa's protectionism prioritized industrial heartland interests over western agricultural needs; these demands gained traction through the Progressive Party, which secured 65 federal seats in 1921 on a platform of agrarian reform.[24] In Alberta, the United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) captured provincial power in 1921, implementing policies to address local grievances but facing federal resistance to broader changes.[25] The Great Depression, beginning with the 1929 stock market crash, devastated the prairies more severely than other regions, as wheat prices collapsed from $1.05 per bushel in 1929 to $0.31 by 1932 amid overproduction, global surpluses, and the Dust Bowl droughts that eroded topsoil across southern Saskatchewan and Alberta, displacing over 100,000 farmers.[26] Unemployment soared to 30% in prairie urban centers, and federal relief under Prime Ministers Mackenzie King and R.B. Bennett—limited to work camps and minimal direct aid—was criticized as inadequate and oriented toward eastern industrial recovery rather than agricultural relief, fueling perceptions of systemic neglect.[27] Political dissent intensified, with groups like the Ginger Group of Progressive MPs breaking from the Liberals to advocate for monetary reform and tariff abolition, laying groundwork for later autonomy movements as westerners viewed federal policies as perpetuating economic extraction without equitable support.[25]Post-War Resource Expansion and National Energy Program (1940s–1980s)

The discovery of a major oil deposit at Leduc No. 1 on February 13, 1947, marked the onset of Alberta's post-war petroleum boom, shifting the province's economic base toward fossil fuel extraction after decades of limited success in earlier drilling efforts.[28] This find in the Devonian Nisku Formation prompted widespread exploration, drawing American capital and expertise that expanded production across central Alberta and beyond, with initial flows exceeding 1,400 barrels per day from the well.[29] By the 1950s, Alberta had emerged as Canada's leading oil producer, supporting infrastructure like the Interprovincial Pipeline (completed 1950) to deliver crude to refineries in Ontario and Quebec.[28] The 1970s amplified this resource expansion amid global oil shocks, as OPEC embargoes drove prices from $3 per barrel in 1973 to over $30 by 1980, fueling Alberta's GDP growth at rates averaging 5-6% annually and positioning the province as a net exporter of energy wealth to federal coffers via taxes and royalties.[30] Natural gas developments paralleled oil, with Saskatchewan and Alberta pipelines feeding eastern markets, yet provincial governments under leaders like Alberta's Peter Lougheed (premier 1971-1985) asserted ownership rights under the 1930 Natural Resources Transfer Acts, resisting federal encroachments on resource rents.[31] This era underscored Western Canada's causal role in national energy security, as domestic production offset imports and generated fiscal transfers eastward, though without proportional political influence in Ottawa. Tensions peaked with the National Energy Program (NEP), unveiled on October 28, 1980, by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau's Liberal government, which imposed federal price ceilings on oil, escalated taxes on provincial resource revenues to capture up to 50% of industry profits, and mandated Petro-Canada's back-in rights for new projects to promote "Canadianization."[13] Alberta officials, including Lougheed, condemned the NEP as unconstitutional expropriation, arguing it violated provincial jurisdiction and deterred $60 billion in planned investments by hiking effective tax rates to 75% on oil sands projects.[32] The policy accelerated capital outflows, with foreign firms divesting assets and drilling rigs declining 40% by 1982, contributing to Alberta's unemployment surge from under 4% in 1980 to over 12% by 1984 amid concurrent global price collapses.[32] These measures crystallized Western alienation, evoking perceptions of deliberate federal bias favoring Ontario-Quebec manufacturing subsidies over prairie resource economies, as NEP revenues funded eastern job creation while Alberta bore disproportionate regulatory and fiscal burdens.[33] Lougheed's retaliatory production cuts in 1982 forced negotiations, yielding partial concessions like reduced back-in rights, but the program's 1985 repeal under Brian Mulroney's Progressive Conservatives followed electoral backlash, including Liberal wipeouts in Western ridings.[13] Empirical analyses attribute 20-30% of early-1980s western job losses directly to NEP distortions, beyond oil price drops, reinforcing long-term distrust of centralized energy policymaking.[34]Reform Party Emergence (1990s)

The Reform Party of Canada arose in the late 1980s as a populist response to deepening western alienation, particularly after the Progressive Conservative government's 1988 election victory failed to deliver on commitments to Senate reform and regional equity, leaving Western provinces feeling sidelined in federal policy-making. Founded in November 1987 in Winnipeg with Preston Manning—son of former Alberta Premier Ernest Manning—as its inaugural leader, the party drew from earlier grassroots efforts like the 1987 Western Assembly on Canada's Economic Future, which highlighted grievances over economic exploitation and underrepresentation. Initial support was concentrated in Alberta and British Columbia, where voters sought alternatives to established parties perceived as beholden to Central Canadian interests.[35][36] The party's platform directly targeted core elements of western alienation, including demands for a "Triple-E" Senate (elected, equal per province, and effective in checking House legislation) to counter the appointed upper chamber's bias toward Ontario and Quebec, alongside fiscal conservatism aimed at eliminating federal deficits through spending cuts and reduced equalization payments that transferred Western resource revenues eastward. In the 1993 federal election on October 25, Reform secured a dramatic breakthrough, winning 52 seats—all in the West except for two in Ontario—with 18.7% of the national popular vote amid the Progressive Conservatives' collapse to just 2 seats. This outcome reflected widespread discontent with incoming Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chrétien's policies, which prioritized deficit reduction but maintained federal interventions in energy and transfers that exacerbated perceptions of Western subsidization of other regions.[37][38][39] Reform's 1997 election gains further entrenched it as the West's dominant conservative force, capturing 60 seats (20.5% of the vote) and official opposition status, primarily by consolidating rural, small-business, and resource-sector voters alienated by federal regulatory burdens and the absence of democratic reforms. Manning's "The West Wants In" slogan emphasized inclusion over independence, advocating citizen-initiated referendums and provincial autonomy to address causal factors like disproportionate seat representation—where Western provinces held only 28% of Commons seats despite 32% of population—and policy biases in areas such as trade and immigration. While the party's Western-centric focus limited national appeal, it pressured mainstream parties toward fiscal restraint and decentralization, though critics noted its social conservatism occasionally alienated urban moderates.[38][40][35]Economic Underpinnings

Fiscal Transfers and Equalization Payments

Canada's equalization program, enacted in 1957 under the Constitution Act, 1982, transfers federal funds to provinces unable to generate sufficient revenue for comparable public services at average tax rates, calculated based on fiscal capacity from five revenue sources excluding equalized transfers.[41] The formula assesses per capita fiscal capacity against a national standard, with payments to provinces below that threshold; non-renewable resource revenues are partially excluded (50 percent since 2009) to mitigate disincentives for extraction.[42] In fiscal year 2024-25, total equalization payments reached $25.3 billion, distributed solely to "have-not" provinces including Quebec ($13.56 billion), Manitoba, and the Atlantic provinces, while Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia received none due to their resource-driven fiscal capacities exceeding the standard.[43][44] Alberta, a consistent net contributor, has received no equalization payments since 1964-65, despite its residents paying disproportionately high federal taxes relative to population due to elevated per capita GDP from oil and gas.[12] Estimates indicate Alberta taxpayers have funded approximately $67 billion of the program since 1957, equivalent to $20,200 per Albertan, through pooled federal revenues where high-income provinces implicitly subsidize recipients.[45] From 2000 to 2019, Alberta's net fiscal outflow—federal spending received minus taxes paid—totaled $324 billion across all transfers, or $79,870 per capita, far exceeding contributions from other donor provinces like Ontario.[46] Broader net contributions to federal finances from 2007 to 2022 amounted to $244.6 billion for Alberta, over five times British Columbia's $46.9 billion and reflecting resource sector volatility not fully offset by per capita transfers like the Canada Health Transfer ($52.2 billion nationally in 2024-25).[47][48] This fiscal asymmetry exacerbates Western alienation, as Alberta and Saskatchewan perceive equalization as a one-way extraction of resource wealth to finance services in recipient provinces—particularly Quebec, which has received payments annually since inception—without mechanisms for donor input or reciprocity.[44] Critics, including the Fraser Institute, argue the program's growth amid converging provincial capacities (e.g., resource exclusions shielding recipients from full fiscal accountability) perpetuates imbalances, with Alberta's oil sands revenues funding transfers despite federal policies constraining domestic production.[43][49] Proponents counter that transfers are population-based for non-equalization programs and formula-driven, not targeted extraction, though net donor status persists due to economic structure rather than deliberate bias.[42] Empirical data on net flows, however, substantiate grievances of fiscal exploitation, fueling demands for reform such as a cap on payments or resource revenue exemptions.[46]Resource Revenue Disparities

The equalization program's treatment of non-renewable resource revenues underscores fiscal disparities affecting Western provinces, where high provincial royalties from oil, natural gas, and minerals inflate fiscal capacity calculations, disqualifying Alberta and Saskatchewan from receiving payments despite their outsized contributions to national energy production. Under the formula, 50% of actual non-renewable resource revenues—defined as royalties, rents, bonuses, and provincial shares of resource taxes—are incorporated into a province's representative tax system to assess revenue-raising potential against a national standard.[50] This mechanism, adjusted in 2007 to include only half of such revenues (up from full inclusion previously), partially mitigates disincentives for resource extraction but ensures that booming sectors in Western Canada, which account for over 80% of national oil sands output in Alberta alone, systematically elevate fiscal capacity beyond the threshold.[51][52] In practice, these dynamics result in zero equalization entitlements for Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia in recent years, including the 2023-24 fiscal year, while provinces like Quebec received the largest share of the $24 billion total program outlay. Alberta has not qualified for payments since the early 1960s, when resource revenues were first fully integrated into capacity assessments, leading to persistent net fiscal outflows estimated at $3.3 billion from Albertan federal tax contributions in 2023 alone. Saskatchewan similarly reports no receipts over the past 15 years as of 2024, with resource-driven fiscal strength—bolstered by potash and oil—positioning it among "have" provinces despite per capita spending pressures from volatile commodity prices.[53][11][51] Critics, including analyses from independent think tanks, argue that the formula's resource component creates moral hazard by capping upside for high-output provinces without reciprocal infrastructure or development support, fostering alienation as federal policies like pipeline restrictions further constrain revenue potential. For example, equalization's reliance on federal general revenues—disproportionately sourced from higher-income resource economies—effectively transfers Western gains eastward, with Alberta's net contribution exceeding $2.9 billion in 2021 amid subdued global prices. This structure, while constitutionally entrenched under section 36(2) of the Constitution Act, 1982, amplifies grievances by linking provincial prosperity to national redistribution without opt-out provisions or resource-specific offsets.[54][45][55]| Province | Equalization Entitlement (2023-24, CAD billions) | Receives Payment? | Primary Resource Influence on Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | No | High oil/gas royalties exclude eligibility[53] |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | No | Oil, potash revenues boost capacity above standard[51] |

| Quebec | ~13 (largest recipient) | Yes | Lower resource base yields entitlement[53] |

| Total Program | 24 | N/A | Resource formula at 50% inclusion[41] |