Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

World3

View on WikipediaThe World3 model is a system dynamics model for computer simulation of interactions between population, industrial growth, food production and limits in the ecosystems of the earth. It was originally produced and used by a Club of Rome study that produced the model and the book The Limits to Growth (1972). The creators of the model were Dennis Meadows, project manager, and a team of 16 researchers.[1]: 8

The model was documented in the book Dynamics of Growth in a Finite World. It added new features to Jay Wright Forrester's World2 model. Since World3 was originally created, it has had minor tweaks to get to the World3/91 model used in the book Beyond the Limits, later improved to get the World3/2000 model distributed by the Institute for Policy and Social Science Research and finally the World3/2004 model used in the book Limits to Growth: the 30 year update.[2]

World3 is one of several global models that have been generated throughout the world (Mesarovic/Pestel Model, Bariloche Model, MOIRA Model, SARU Model, FUGI Model) and is probably the model that generated the spark for all later models [citation needed].

Model

[edit]The model consisted of several interacting parts. Each of these dealt with a different system of the model. The main systems were

- the food system, dealing with agriculture and food production

- the industrial system

- the population system

- the non-renewable resources system

- the pollution system

Agricultural system

[edit]The simplest useful view of this system is that land and fertilizer are used for farming, and more of either will produce more food. In the context of the model, since land is finite, and industrial output required to produce fertilizer and other agricultural inputs can not keep up with demand, there necessarily will be a food collapse at some point in the future.

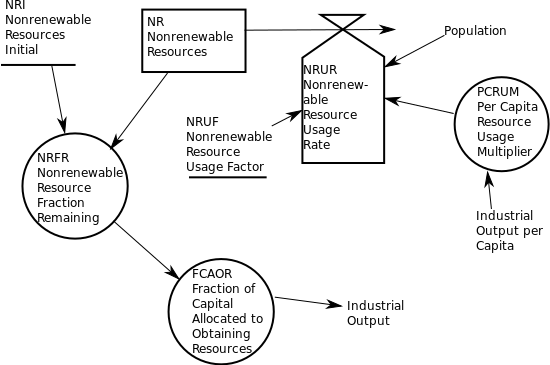

Nonrenewable resources system

[edit]The nonrenewable resource system starts with the assumption that the total amount of resources available is finite (about 110 times the consumption at 1990s rates for the World3/91 model). These resources can be extracted and then used for various purposes in other systems in the model. An important assumption that was made is that as the nonrenewable resources are extracted, the remaining resources are increasingly difficult to extract, thus diverting more and more industrial output to resource extraction.

The model combines all possible nonrenewable resources into one aggregate variable, nonrenewable_resources.[3]: 387 This combines both energy resources and non-energy resources. Examples of nonrenewable energy resources would include oil and coal. Examples of material nonrenewable resources would include aluminum and zinc. This assumption allows costless substitution between any nonrenewable resource. The model ignores differences between discovered resources and undiscovered resources.[3]: 381

The model assumes that as greater percentages of total nonrenewable resources are used, the amount of effort used to extract the nonrenewable resources will increase.

The way this cost is done is as a variable fraction_of_capital_allocated_to_obtaining_resources, or abbreviated fcaor.[3]: 393–8 The way this variable is used is in the equation that calculates industrial output. Basically, it works as effective_output = industrial_capital*other_factors*(1-fcaor). This causes the amount of resources expended to depend on the amount of industrial capital, and not on the amount of resources consumed.[3]: 390–3

The consumption of nonrenewable resources is determined by a nonlinear function of the per capita industrial output. The higher the per capita industrial output, the higher the nonrenewable resource consumption.

Reference run predictions

[edit]The Dynamics of Growth in a Finite World provides several different scenarios. The "reference run" is the one that "represent the most likely behavior mode of the system if the process of industrialization in the future proceeds in a way very similar to its progress in the past, and if technologies and value changes that have already been institutionalized continue to evolve."[4]: 502 In this scenario, in 2000, the world population reaches six billion, and then goes on to peak at seven billion in 2030. After that population declines because of an increased death rate. In 2015, both industrial output per capita and food per capita peak at US$375 per person (1970s dollars, about $2,820 today) and 500 vegetable-equivalent kilograms/person. Persistent pollution peaks in the year 2035 at 11 times 1970s levels.[4]: 500

Criticism of the model

[edit]There has been criticism of the World3 model. Some has come from the model creators themselves, some has come from economists and some has come from other places.

In the book Groping in the Dark: The First Decade of Global Modelling,[5]: 129 Donella Meadows (a Limits author) writes:

We have great confidence in the basic qualitative assumptions and conclusions about the instability of the current global socioeconomic system and the general kinds of changes that will and will not lead to stability. We have relatively great confidence in the feedback-loop structure of the model, with some exceptions which I list below. We have a mixed degree of confidence in the numerical parameters of the model; some are well-known physical or biological constants that are unlikely to change, some are statistically derived social indices quite likely to change, and some are pure guesses that are perhaps only of the right order of magnitude. The structural assumptions in World3 that I consider most dubious and also sensitive enough to be of concern are:

- the constant capital-output ratio (which assumes no diminishing returns to capital)

- the residual nature of the investment function

- the generally ineffective labour contribution to output

A detailed criticism of the model is in the book Models of Doom: A Critique of the Limits to Growth.[6]: 905–908

Czech-Canadian scientist and policy analyst Vaclav Smil disagreed with the combination of physically different processes into simplified equations:

But those of us who knew the DYNAMO language in which the simulation was written and those who took the model apart line-by-line quickly realized that we had to deal with an exercise in misinformation and obfustication rather than with a model delivering valuable insights. I was particularly astonished by the variables labelled Nonrenewable Resources and Pollution. Lumping together (to cite just a few scores of possible examples) highly substitutable but relatively limited resources of liquid oil with unsubstitutable but immense deposits of sedimentary phosphate rocks, or short-lived atmospheric gases with long-lived radioactive wastes, struck me as extraordinarily meaningless.[7]: 168

He does however consider continuous growth in world GDP a problem:

Only the widespread scientific illiteracy and innumeracy—all you need to know in this case is how to execute the equation —prevents most of the people from dismissing the idea of sustainable growth at healthy rates as an oxymoronic stupidity whose pursuit is, unfortunately, infinitely more tragic than comic. After all, even cancerous cells stop growing once they have destroyed the invaded tissues.[7]: 338–339

Others have put forth criticisms, such as Henshaw, King, and Zarnikau who in a 2011 paper, Systems Energy Assessment[8] point out that the methodology of such models may be valid empirically as a world model, but might not then also be useful for decision making. The impact data being used is generally collected according to where the impacts are recorded as occurring, following standard I/O material processes accounting methods. It is not reorganized according to who pays for or profits from the impacts, so who is actually responsible for economic impacts is never determined. In their view

- The economic motives causing the impacts, that might also control them, would then not be reflected in the model.

- As a seeming technicality, it could bring into question the use of many kinds of economic models for sustainability decision-making.

The authors of the book Surviving 1,000 Centuries consider some of the predictions too pessimistic, but some of the overall message correct.[9]: 4–5

...[We] come to the well-known study, Limits to Growth, published under the sponsorship of the 'Club de Rome' - an influential body of private individuals. A first attempt was made to make a complete systems analysis of the rapidly growing human-biological-resource-pollution system. In this analysis the manifold interactions between the different parts were explicitly taken into account. The conclusion was that disaster was waiting around the corner in a few decades because of resource exhaustion, pollution and other factors. Now, 35 years later, our world still exists, ... So the 'growth lobby' has laughed and proclaimed that Limits to Growth and, by extension, the environmental movements may be forgotten. This entirely misses the point. Certainly the timescale of the problems was underestimated in Limits to Growth, giving us a little more time than we thought. Moreover, during the last three decades a variety of national or collaborative international measures have been taken that have forced reductions in pollution, as we shall discuss. A shining example of this is the Montreal Protocol (1987) that limited the industrial production of fluorocarbons that damage the ozone layer and generated the 'ozone hole' over Antarctica. The publication of Limits to Growth has greatly contributed towards creating the general willingness of governments to consider such issues. Technological developments have also lead to improvements in the efficiency of the use of energy and other resources, but, most importantly, the warnings from Malthus onward have finally had their effect as may be seen from the population-limiting policies followed by China and, more hesitantly, by India. Without such policies all other efforts would be in vain. However, the basic message of Limits to Growth, that exponential growth of our world civilization cannot continue very long and that a very careful management of the planet is needed, remain as valid as ever.

At least one study disagrees with the criticism. Writing in the journal Global Environmental Change, Turner notes that "30 years of historical data compare favorably with key features of the 'business-as-usual' scenario called the 'standard run' produced by the World3 model".[10]

Validation

[edit]A number of researchers have attempted to test the predictions of the World3 model against observed data, with varying conclusions. Recent results published in Yale's Journal of Industrial Ecology[11][12] found that current empirical data is broadly consistent with the 1972 projections, and that if major changes to the consumption of resources are not undertaken, economic growth will peak and then rapidly decline by around 2040.[13][14]

References

[edit]- ^ Meadows, Donella H; Meadows, Dennis L; Randers, Jørgen; Behrens III, William W (1972). The Limits to Growth; A Report for the Club of Rome's Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books. ISBN 0876631650. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Meadows, Donella; Randers, Jorgen; Meadows, Dennis. "A Synopsis: Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update". Donella Meadows Project. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d Meadows, Dennis L.; Behrens, III, William W.; Meadows, Donella H.; Naill, Roger F.; Randers, Jørgan; Zahn, Erich (1974). Dynamics of Growth in a Finite World. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Wright-Allen Press, Inc. ISBN 0-9600294-4-3.

- ^ a b Meadows, Dennis L.; et al. (1974). Dynamics of Growth in a Finite World. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0262131420. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Meadows, Donella H. (1982). Groping in the dark: the first decade of global modelling. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471100277. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Cole, H. S. D.; Freeman, Christopher (1973). Models of Doom: A Critique of the Limits to Growth. Vhps Rizzoli. ISBN 0876639058.

- ^ a b Smil, Vaclav (2005). Energy at the Crossroads; Global Perspectives and Uncertainties. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262693240. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Henshaw, King, Zarnikau, 2011 Systems Energy Assessment. Sustainability, 3(10), 1908-1943; doi:10.3390/su3101908

- ^ Bonnet, Roger-Maurice; Woltjer, Lodewijk (2008). Surviving 1,000 Centuries; Can we do it?. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 9780387746333. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Turner, G. (2008). "A comparison of the Limits to Growth with 30 years of reality". Global Environmental Change. 18 (3): 397–411. Bibcode:2008GEC....18..397T. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.05.001.

- ^ Herrington, Gaya (2020). "Update to limits to growth: Comparing the World3 model with empirical data". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 25 (3). Wiley: 614–626. doi:10.1111/jiec.13084. S2CID 226019712.

- ^ Nebel, Arjuna; Kling, Alexander; Willamowski, Ruben; Schell, Tim (November 2023). "Recalibration of limits to growth: An update of the World3 model". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 28: 87–99. doi:10.1111/jiec.13442., published online 13 Nov 2023

- ^ Ahmed, Nafeez (14 July 2021). "MIT Predicted in 1972 That Society Will Collapse This Century. New Research Shows We're on Schedule". Vice.com. Study also available here

- ^ Rosane, Olivia (26 July 2021). "1972 Warning of Civilizational Collapse Was on Point, New Study Finds". Ecowatch. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

External links and references

[edit]- "Basic Literature" : selected bibliography on limits to growth with short summary on each publication - published by All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG)

- Dynamics of Growth in a Finite World, by Dennis L. Meadows, William W. Behrens III, Donella H. Meadows, Roger F. Naill, Jorgen Randers, and Erich K.O. Zahn. 1974 ISBN 0-9600294-4-3

- World Dynamics, by Jay Wright Forrester. 1973 ISBN 0-262-56018-6

- The Limits to Growth (Abstract, 8 pages, by Eduard Pestel. A Report to The Club of Rome (1972), by Donella H. Meadows, Dennis l. Meadows, Jorgen Randers, William W. Behrens III)

- Limits to Growth, The 30-Year Update, by Dennis Meadows and Eric Tapley. 2004 CDRom with World3-2004 model. ISBN 1-931498-85-7

- WorldChange Model. This adds a change resistance subsystem to World3 in order to more correctly analyze and simulate why sustainability science has so far been unable to solve the sustainability problem.

Model implementations

[edit]- Javascript world 3 simulator

- Interactive online World3 simulation

- pyworld3 on GitHub - Python version of World3

- MyWorld3 on GitHub - A second Python version of World3

- Macintosh version of the Simulation by Kenneth L. Simons

- Implementation of the World3 model in the simulation language Modelica

- WorldDynamics.jl on GitHub - Julia version of World3 and World2