Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

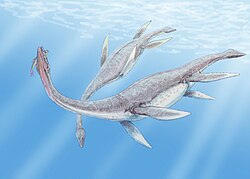

Plesiosauroidea

View on Wikipedia

| Plesiosauroids Temporal range: Late Triassic - Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Clade: | †Neoplesiosauria |

| Superfamily: | †Plesiosauroidea Gray, 1825 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Plesiosauroidea (/ˈpliːsiəsɔːr/; Greek: πλησιος plēsios 'near, close to' and σαυρος sauros 'lizard') is an extinct clade of carnivorous marine reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroids are known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. After their discovery, some plesiosauroids were said to have resembled "a snake threaded through the shell of a turtle",[1] although they had no shell.

Plesiosauroidea appeared at the Early Jurassic Period (late Sinemurian stage) and thrived until the K-Pg extinction, at the end of the Cretaceous Period. The oldest confirmed plesiosauroid is Plesiosaurus itself, as all younger taxa were recently found to be pliosauroids.[2] While they were Mesozoic diapsid reptiles that lived at the same time as dinosaurs, they did not belong to the latter. Gastroliths are frequently found associated with plesiosaurs.[3]

History of discovery

[edit]

The first complete plesiosauroid skeletons were found in England by Mary Anning, in the early 19th century, and were amongst the first fossil vertebrates to be described by science. Plesiosauroid remains were found by the Scottish geologist Hugh Miller in 1844 in the rocks of the Great Estuarine Group (then known as 'Series') of western Scotland.[4] Many others have been found, some of them virtually complete, and new discoveries are made frequently. One of the finest specimens was found in 2002 on the coast of Somerset (England) by someone fishing from the shore. This specimen, called the Collard specimen after its finder, was on display in Taunton Museum in 2007. Another, less complete, skeleton was also found in 2002, in the cliffs at Filey, Yorkshire, England, by an amateur palaeontologist. The preserved skeleton is displayed at Rotunda Museum in Scarborough.

Description

[edit]Plesiosauroids had a broad body and a short tail. They retained their ancestral two pairs of limbs, which evolved into large flippers.

It has been determined by teeth records that several sea-dwelling reptiles, including plesiosauroids, had a warm-blooded metabolism similar to that of mammals. They could generate endothermic heat to survive in colder habitats.[5]

Evolution

[edit]Plesiosauroids evolved from earlier, similar forms such as pistosaurs. There are a number of families of plesiosauroids, which retain the same general appearance and are distinguished by various specific details. These include the Plesiosauridae, unspecialized types which are limited to the Early Jurassic period; Cryptoclididae, (e.g. Cryptoclidus), with a medium-long neck and somewhat stocky build; Elasmosauridae, with very long, flexible necks and tiny heads; and the Cimoliasauridae, a poorly known group of small Cretaceous forms. According to traditional classifications, all plesiosauroids have a small head and long neck but, in recent classifications, one short-necked and large-headed Cretaceous group, the Polycotylidae, are included under the Plesiosauroidea, rather than under the traditional Pliosauroidea. Size of different plesiosaurs varied significantly, with an estimated length of Trinacromerum being three meters and Mauisaurus growing to twenty meters.

Relationships

[edit]

Within Plesiosauroidea, there is a more exclusive group, Cryptoclidia. Cryptoclidia was named and defined as a node clade in 2010 by Hilary Ketchum and Roger Benson: the group consisting of the last common ancestor of Cryptoclidus eurymerus and Polycotylus latipinnis; and all its descendants.[6]

The smaller group within Cryptoclidia was erected prior, in 2007 under the name "Leptocleidoidea".[7] Although established as a clade, the name Leptocleidoidea implies that it is a superfamily. Leptocleidoidea is placed within the superfamily Plesiosauroidea, so it was renamed Leptocleidia by Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson (2010) to avoid confusion with ranks. Leptocleidia is a node-based taxon which was defined by Ketchum and Benson as "Leptocleidus superstes, Polycotylus latipinnis, their most recent common ancestor and all of its descendants".[6] The following cladogram follows an analysis by Benson & Druckenmiller (2014).[8]

| Plesiosauroidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Behavior

[edit]

Unlike their pliosauroid cousins, plesiosauroids (with the exception of the Polycotylidae) were probably slow swimmers.[9] It is likely that they cruised slowly below the surface of the water, using their long flexible neck to move their head into position to snap up unwary fish or cephalopods. Their four-flippered swimming adaptation may have given them exceptional maneuverability, so that they could swiftly rotate their bodies as an aid to catching prey.

Contrary to many reconstructions of plesiosauroids, it would have been impossible for them to lift their head and long neck above the surface, in the "swan-like" pose that is often shown.[1][10] Even if they had been able to bend their necks upward to that degree (which they could not), gravity would have tipped their body forward and kept most of the heavy neck in the water.

On 12 August 2011, researchers from the U.S. described a fossil of a pregnant plesiosaur found on a Kansas ranch in 1987.[11] The plesiosauroid, Polycotylus latippinus, has confirmed that these predatory marine reptiles gave birth to single, large, live offspring—contrary to other marine reptile reproduction which typically involves a large number of small babies. Before this study, plesiosauroids had sometimes been portrayed crawling out of water to lay eggs in the manner of sea turtles, but experts had long suspected that their anatomy was not compatible with movement on land. The adult plesiosaur measures 4 m (13 ft) long and the juvenile is 1.5 m (4.9 ft) long.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Everhart, Mike (2005-10-14). "A Snake Drawn Through the Shell of a Turtle". Oceans of Kansas Paleontology. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ^ Ketchum, Hilary F.; Benson, Roger B. J. (2011). "A new pliosaurid (Sauropterygia, Plesiosauria) from the Oxford Clay Formation (Middle Jurassic, Callovian) of England: evidence for a gracile, longirostrine grade of Early-Middle Jurassic pliosaurids". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 109–129.

- ^ "Occurrence of Gastroliths in Mesozoic Taxa," in Sanders et al. (2001). Page 168.

- ^ Trewin, N. H., ed. (2002). The Geology of Scotland. The Geological Society of London. p. 339.

- ^ Bernard, A.; Lecuyer, C.; Vincent, P.; Amiot, R.; Bardet, N.; Buffetaut, E.; Cuny, G.; Fourel, F.; Martineau, F.; Mazin, J.-M.; Prieur, A. (2010-06-15). "Warm-blooded marine reptiles at the time of the dinosaurs". Science. 328 (5984). Sciencedaily.com: 1379–1382. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1379B. doi:10.1126/science.1187443. PMID 20538946. S2CID 206525584. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ^ a b Ketchum, H.F.; Benson, R.B.J. (2010). "Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role of taxon sampling in determining the outcome of phylogenetic analyses". Biological Reviews. 85 (2): 361–392. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00107.x. PMID 20002391. S2CID 12193439.

- ^ Druckenmiller, P.S.; Russel, A.P. (2007). "A phylogeny of Plesiosauria (Sauropterygia) and its bearing on the systematic status of Leptocleidus Andrews, 1922" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1863: 1–120. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1863.1.1. ISBN 978-1-86977-262-8. ISSN 1175-5334. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-04.

- ^ Benson, R. B. J.; Druckenmiller, P. S. (2013). "Faunal turnover of marine tetrapods during the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition". Biological Reviews. 89 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1111/brv.12038. PMID 23581455. S2CID 19710180.

- ^ Massare, J. A. (1988). "Swimming capabilities of Mesozoic marine reptiles: Implications for method of predation". Paleobiology. 14 (2): 187–205. Bibcode:1988Pbio...14..187M. doi:10.1017/s009483730001191x. S2CID 85810360.

- ^ Henderson, D. M. (2006). "Floating point: a computational study of buoyancy, equilibrium, and gastroliths in plesiosaurs" (PDF). Lethaia. 39 (3): 227–244. Bibcode:2006Letha..39..227H. doi:10.1080/00241160600799846.

- ^ F. R. O’Keefe1,*, L. M. Chiappe2 (2011). "Viviparity and K-Selected Life History in a Mesozoic Marine Plesiosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia)". Science. 333 (6044). Sciencemag.org: 870–873. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..870O. doi:10.1126/science.1205689. PMID 21836013. S2CID 36165835. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Anthony King. "Ancient sea dragons had a caring side". Cosmosmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

Sources

[edit]- Carpenter, K (1996). "A review of short-necked plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior, North America" (PDF). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 201 (2): 259–287. doi:10.1127/njgpa/201/1996/259.

- Carpenter, K. 1997. "Comparative cranial anatomy of two North American Cretaceous plesiosaurs". Pp. 91–216, in Calloway J. M. and E. L. Nicholls, (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, San Diego.

- Carpenter, K (1999). "Revision of North American elasmosaurs from the Cretaceous of the western interior". Paludicola. 2 (2): 148–173.

- Cicimurri, D. J.; Everhart, M. J. (2001). "An elasmosaur with stomach contents and gastroliths form the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous) of Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 104 (3–4): 129–143. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2001)104[0129:aewsca]2.0.co;2. S2CID 86037286.

- Cope, E. D. (1868). "Remarks on a new enaliosaurian, Elasmosaurus platyurus". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 20: 92–93.

- Ellis, R. 2003. Sea Dragons' (Kansas University Press)

- Everhart, M. J. (2000). "Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member of the Pierre Shale (Late Cretaceous), western Kansas". Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 103 (1–2): 58–69. doi:10.2307/3627940. JSTOR 3627940.

- Everhart, M. J. (2002). "Where the elasmosaurs roam...". Prehistoric Times. 53: 24–27.

- Everhart, M. J. (2004). "Plesiosaurs as the food of mosasaurs; new data on the stomach contents of a Tylosaurus proriger (Squamata; Mosasauridae) from the Niobrara Formation of western Kansas". The Mosasaur. 7: 41–46.

- Everhart, M. J. (2005). "Bite marks on an elasmosaur (Sauropterygia; Plesiosauria) paddle from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) as probable evidence of feeding by the lamniform shark, Cretoxyrhina mantelli". PalArch. 2 (2): 14–24.

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. "Where the Elasmosaurs roamed", Chapter 7 in Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 322 p.

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. "Gastroliths associated with plesiosaur remains in the Sharon Springs Member (Late Cretaceous) of the Pierre Shale, Western Kansas" (on-line, updated from article in Kansas Acad. Sci. Trans. 103(1-2):58-69)

- Everhart, M. J. (2005). "Probable plesiosaur gastroliths from the basal Kiowa Shale (Early Cretaceous) of Kiowa County, Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 108 (3/4): 109–115. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2005)108[0109:ppgftb]2.0.co;2. S2CID 86124216.

- Everhart, M. J. (2005). "Elasmosaurid remains from the Pierre Shale (Upper Cretaceous) of western Kansas. Possible missing elements of the type specimen of Elasmosaurus platyurus Cope 1868?". PalArch. 4 (3): 19–32.

- Everhart, M. J. (2006). "The occurrence of elasmosaurids (Reptilia: Plesiosauria) in the Niobrara Chalk of Western Kansas". Paludicola. 5 (4): 170–183.

- Everhart, M. J. (2007). "Use of archival photographs to rediscover the locality of the Holyrood elasmosaur (Ellsworth County, Kansas)". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 110 (1/2): 135–143. doi:10.1660/0022-8443(2007)110[135:uoaptr]2.0.co;2. S2CID 86051586.

- Everhart, M. J. 2007. Sea Monsters: Prehistoric Creatures of the Deep. National Geographic, 192 p. ISBN 978-1-4262-0085-4.

- Everhart, M. J. "Marine Reptile References" and scans of "Early papers on North American plesiosaurs"

- Hampe, O., 1992: Courier Forsch.-Inst. Senckenberg 145: 1-32.

- Lingham-Soliar, T (1995). "in". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 347: 155–180.

- O'Keefe, F. R. (2001). "A cladistic analysis and taxonomic revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia);". Acta Zool. Fennica. 213: 1–63.

- Massare, J. A. (1988). "Swimming capabilities of Mesozoic marine reptiles: Implications for method of predation". Paleobiology. 14 (2): 187–205. Bibcode:1988Pbio...14..187M. doi:10.1017/s009483730001191x. S2CID 85810360.

- Massare, J. A. 1994. Swimming capabilities of Mesozoic marine reptiles: a review. pp. 133–149 In Maddock, L., Bone, Q., and Rayner, J. M. V. (eds.), Mechanics and Physiology of Animal Swimming, Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, A. S. 2008. Fossils explained 54: plesiosaurs. Geology Today. 24, (2), 71-75 PDF document on the Plesiosaur Directory

- Storrs, G. W., 1999. An examination of Plesiosauria (Diapsida: Sauropterygia) from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of central North America, University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions, (N.S.), No. 11, 15 pp.

- Welles, S. P. 1943. Elasmosaurid plesiosaurs with a description of the new material from California and Colorado. University of California Memoirs 13:125-254. figs. 1-37., pls. 12–29.

- Welles, S. P. 1952. A review of the North American Cretaceous elasmosaurs. University of California Publications in Geological Science 29:46-144, figs. 1-25.

- Welles, S. P. 1962. A new species of elasmosaur from the Aptian of Columbia and a review of the Cretaceous plesiosaurs. University of California Publications in Geological Science 46, 96 pp.

- White, T (1935). "in". Occasional Papers Boston Soc. Nat. Hist. 8: 219–228.

- Williston, S. W. (1890). "A new plesiosaur from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 12: 174–178. doi:10.2307/3623798. JSTOR 3623798., 2 fig.

- Williston, S. W. 1902. Restoration of Dolichorhynchops osborni, a new Cretaceous plesiosaur. Kansas University Science Bulletin, 1(9):241-244, 1 plate.

- Williston, S. W. 1903. North American plesiosaurs. Field Columbian Museum, Publication 73, Geology Series 2(1): 1-79, 29 pl.

- Williston, S. W. (1906). "North American plesiosaurs: Elasmosaurus, Cimoliasaurus, and Polycotylus". American Journal of Science. 4. 21 (123): 221–234. Bibcode:1906AmJS...21..221W. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-21.123.221., 4 pl.

- Williston, S. W. (1908). "North American plesiosaurs: Trinacromerum". Journal of Geology. 16 (8): 715–735. Bibcode:1908JG.....16..715W. doi:10.1086/621573. S2CID 129889740.

- ( ), 1997: in Reports of the National Center for Science Education, 17.3 (May/June 1997) pp 16–28.

External links

[edit]- Fox News: Possibly Complete Plesiosaur Skeleton Found in Arctic

- The Plesiosaur Site. Richard Forrest.

- The Plesiosaur Directory. Dr Adam Stuart Smith.

- The name game: plesiosaur-ia, -oidea, -idae, or -us?.

- Oceans of Kansas Paleontology. Mike Everhart.

- Where the elasmosaurs roam: Separating fact from fiction. Mike Everhart.

- Triassic reptiles had live young

- The Filey (Yorkshire) Plesiosaur 2002 (part 1)

- The Filey (Yorkshire) Plesiosaur 2002 (part 2)

- Antarctic Researchers to Discuss Difficult Recovery of Unique Juvenile Plesiosaur Fossil, from the National Science Foundation, December 6, 2006.

- "Fossil hunters turn up 50-ton monster of prehistoric deep". Allan Hall and Mark Henderson. Times Online, December 30, 2002. (Monster of Aramberri)