Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Zurvanism

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2025) |

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

Zurvanism was a fatalistic religious movement of Zoroastrianism[1] in which the divinity Zurvan is a first principle (primordial creator deity) who engendered equal-but-opposite twins, Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu. Zurvanism is also known as "Zurvanite Zoroastrianism", and may be contrasted with Mazdaism.

In Zurvanism, Zurvan was perceived as the god of infinite time and space and also known as "one" or "alone." Zurvan was portrayed as a transcendental and neutral god without passion; one for whom there was no distinction between good and evil. The name Zurvan is a normalized rendition of the word, which in Middle Persian appears as either Zurvān, Zruvān or Zarvān. The Middle Persian name derives from Avestan (Avestan: 𐬰𐬭𐬎𐬎𐬁𐬥, romanized: zruuān, lit. 'time', a grammatically neuter noun).

Origins and background

[edit]Although the details of the origin and development of Zurvanism remain murky (for a summary of the three opposing opinions see § Ascent and acceptance below), it is generally accepted that Zurvanism was:

- (1) a branch of greater Zoroastrianism;[2]: 157–304

- (2) a sacerdotal response to resolve a perceived inconsistency in the sacred texts[3]: intro (see § The "twin brother" doctrine below);

- (3) probably introduced during the second half of the Achaemenid era.[4][2]: 157–304

Zurvanism enjoyed royal sanction during the Sasanian Empire (226–651 CE) but no traces of it remain beyond the 10th century. Although Sasanian-era Zurvanism was certainly influenced by Hellenic philosophy, any relationship between it and the Greek divinity of Chronos "Time" has not been conclusively established. Non-Zoroastrian accounts of typically Zurvanite beliefs were the first traces of Zoroastrianism to reach the west, leading European scholars to conclude that Zoroastrianism was a monist religion, an issue of controversy among both scholars and contemporary practitioners of the faith.

Evidence of the cult

[edit]The earliest evidence of the cult of Zurvan is found in the History of Theology, attributed to Eudemus of Rhodes (c. 370–300 BCE). As cited in Damascius's Difficulties and Solutions of First Principles (6th century CE), Eudemus describes a sect of the Medes that considered Space/Time to be the primordial "father" of the rivals Oromasdes "of light" and Arimanius "of darkness".[5]: 331–332

The principal evidence for Zurvanite doctrine occurs in the polemical Christian tracts of Armenian and Syriac writers of the Sasanian period (224–651 CE). Indigenous sources of information from the same period are the 3rd century Kartir inscription at Ka'ba-ye Zartosht and the early 4th-century edict of Mihr-Narseh, the mowbadān-mowbad or high priest under Yazdegerd I, the latter being the only native evidence from the Sasanian period that is frankly Zurvanite. The post-Sasanian Zoroastrian Middle Persian commentaries are primarily Mazdean and with only one exception (the 10th century Denkard 9.30[6]) do not mention Zurvan at all.

Of the remaining so-called Pahlavi books, only two, the Mēnōg-i Khrad and the Selections of Zādspram (both 9th century) reveal a Zurvanite tendency. The latter, in which the priest Zādspram chastises his brother's un-Mazdaean ideas,[7] is the last text in Middle Persian that provides any evidence of the cult of Zurvan. The 13th century Zoroastrian Ulema-i Islam ([Response] to Doctors of Islam), a New Persian apologetic text, is unambiguously Zurvanite and is also the last direct evidence of Zurvan as a First Principle.

There is no hint of any worship of Zurvan in any of the texts of the Avesta, even though the texts (as they exist today) are the result of a Sasanian era redaction. Robert Charles Zaehner proposed that this is because the individual Sasanian monarchs were not always Zurvanite and that Mazdean Zoroastrianism just happened to have the upper hand during the crucial period that the canon was finally written down.[3]: 48 [8]: 108 In the texts composed prior to the Sasanian period, Zurvan appears twice, as both an abstract concept and as a minor divinity, but there is no evidence of a cult. In Yasna 72.10 Zurvan is invoked in the company of Space and Air (Vata-Vayu) and in Yasht 13.56, the plants grow in the manner Time has ordained according to the will of Ahura Mazda and the Amesha Spentas. Two other references to Zurvan are also present in the Vendidad, but although these are late additions to the canon, they again do not establish any evidence of a cult. Zurvan does not appear in any listing of the Yazatas.[5]

History and development

[edit]Ascent and acceptance

[edit]The origins of the cult of Zurvan remain debated. One view[9][8][3]: intro considers Zurvanism to have developed out of Zoroastrianism as a reaction to the liberalization of the late Achaemenid-era form of the faith. Another view[a] proposes that Zurvan existed as a pre-Zoroastrian divinity that was incorporated into Zoroastrianism. The third view[11][4][2] is that Zurvanism is the product of the contact between Zoroastrianism and Babylonian–Akkadian religions (for a summary of opposing views see Boyce[2]: 304 ).

Certain however is that by the Sasanian Empire (226–651), the divinity "Infinite Time" was well established, and – as inferred from a Manichaean text presented to Shapur I, in which the name Zurvan was adopted for Manichaeism's primordial "Father of Greatness" [citation needed] – enjoyed royal patronage. It was during the reign of Sasanian Emperor Shapur I (241–272 CE) that Zurvanism appears to have developed as a cult and it was presumably in this period that Greek and Indic concepts were introduced to Zurvanite Zoroastrianism.

It is however not known whether Sasanian-era Zurvanism and Mazdaism were separate sects, each with their own organization and priesthood, or simply two tendencies within the same body. That Mazdaism and Zurvanism competed for attention has been inferred from the works of Christian and Manichaean polemicists, but the doctrinal incompatibilities were not so extreme "that they could not be reconciled under the broad aegis of an imperial church".[2]: 30 More likely is that the two sects served different segments of Sasanian society, with dispassionate Zurvanism primarily operating as a mystic cult and passionate Mazdaism serving the community at large.

Decline and disappearance

[edit]

Following the fall of the Sasanian Empire in the 7th century, Zoroastrianism was gradually supplanted by Islam. The former continued to exist but in an increasingly reduced state, and by the 10th century the remaining Zoroastrians appear to have more closely followed the orthodoxy as found in the Pahlavi books (see also § The legacy of Zurvanism below).

Why the cult of Zurvan vanished, while Mazdaism did not, remains an issue of scholarly debate. Arthur Christensen, one of the first proponents of the theory that Zurvanism was the state religion of the Sasanians, suggested that the rejection of Zurvanism in the post-conquest epoch was a response and reaction to the new authority of Islamic monotheism that brought about a deliberate reform of Zoroastrianism that aimed to establish a stronger orthodoxy.[2]: 305 Zaehner is of the opinion that the Zurvanite priesthood had a "strict orthodoxy which few could tolerate. Moreover, they interpreted the Prophet's message so dualistically that their God was made to appear very much less than all-powerful and all-wise. As reasonable as it might have appeared from a purely intellectual point of view, such an absolute dualism had neither the appeal of a real monotheism nor any mystical element with which to nourish its inner life."[12]

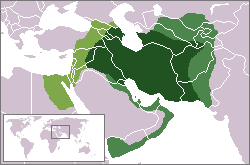

Another possible explanation postulated by Boyce[2]: 308–309 is that Mazdaism and Zurvanism were divided regionally; that is, with Mazdaism being the predominant tendency in the regions to the north and east (Bactria, Margiana, and other satrapies closest to Zoroaster's homeland), while Zurvanism was prominent in regions to the south and west (closer to Babylonian and Greek influence). This is supported by Manichaean evidence that indicates that 3rd century Mazdean Zoroastrianism had its stronghold in Parthia, to the northeast. Following the fall of the Persian Empire, the south and west were relatively quickly assimilated under the banner of Islam, while the north and east remained independent for some time before these regions too were absorbed.[2]: 308–309 This could also explain why Armenian/Syriac observations reveal a distinctly Zurvanite Zoroastrianism, and inversely, could explain the strong Greek and Babylonian connection and interaction with Zurvanism (see § Types of Zurvanism below).

The "twin brother" doctrine

[edit]"Classical Zurvanism" is a term coined by Zaehner[3]: intro to denote the movement to explain the inconsistency of Zoroaster's description of the "twin spirits" as they appear in Yasna 30.3–5 of the Avesta. According to Zaehner, this "Zurvanism proper" was

genuinely Iranian and Zoroastrian in that it sought to clarify the enigma of the twin spirits that Zoroaster left unsolved.[12]

As the priesthood sought to explain it, if the Malevolent Spirit (lit: Angra Mainyu) and the Benevolent Spirit (Spenta Mainyu, identified with Ahura Mazda) were twins, then they must have had a parent, who must have existed before them. The priesthood settled on Zurvan – the hypostasis of (Infinite) Time – as being "the only possible 'Absolute' from whom the twins could proceed" and which was the source of good in the one and the source of evil in the other.[12]

The Zurvanite "twin brother" doctrine is also evident in Zurvanism's cosmogonical creation myth; the classic form of the creation myth does not contradict the Mazdean model of the origin and evolution of the universe, which begins where the Zurvanite model ends. It may well be that the Zurvanite cosmogony was an adaptation of an antecedent Hellenic Chronos cosmogony that portrayed Infinite Time as the "Father of Time" (not to be confused with the Titan Cronus, father of Zeus) whom the Greeks equated with Oromasdes, i.e. Ohrmuzd / Ahura Mazda.[11]

Creation story

[edit]The classic Zurvanite model of creation, preserved only by non-Zoroastrian sources, proceeds as follows:

In the beginning, the great God Zurvan existed alone. Desiring offspring that would create "heaven and hell and everything in between", Zurvan sacrificed for a thousand years. Towards the end of this period, androgyne Zurvan began to doubt the efficacy of sacrifice and in the moment of this doubt Ohrmuzd and Ahriman were conceived: Ohrmuzd for the sacrifice and Ahriman for the doubt. Upon realizing that twins were to be born, Zurvan resolved to grant the first-born sovereignty over creation. Ohrmuzd perceived Zurvan's decision, which He then communicated to His brother. Ahriman then preempted Ohrmuzd by ripping open the womb to emerge first. Reminded of the resolution to grant Ahriman sovereignty, Zurvan conceded, but limited kingship to a period of 9,000 years, after which Ohrmuzd would rule for all eternity.[3]: 419–428

Christian and Manichaean missionaries considered this doctrine to be exemplary of the Zoroastrian faith and it was these and similar texts that first reached the west. Corroborated by Anquetil-Duperron's "erroneous rendering" of Vendidad 19.9, these led to the late 18th-century century conclusion that Infinite Time was the first Principle of Zoroastrianism and Ohrmuzd was therefore only "the derivative and secondary character". Ironically, the fact that no Zoroastrian texts contained any hint of the born-of-Zurvan doctrine was considered to be evidence of a latter-day corruption of the original principles. The opinion that Zoroastrianism was so severely dualistic that it was, in fact, ditheistic or even tritheistic would be widely held until the late 19th century.[5]: 490–492 [13]: 687

Zurvan wife

[edit]In some Zurvanite narratives, it is mentioned that Zurvan had a wife and had children with Ahura Mazda and Ahriman, later, Ahura Mazda married his mother and had children with her, including the sun, dogs, pigs, donkeys, and cattle.[14]

Types of Zurvanism

[edit]According to Zaehner,[3][12] the doctrine of the cult of Zurvan appears to have three schools of thought, each to a different degree influenced by alien philosophies, which he calls

- materialist Zurvanism,

- ascetic Zurvanism, and

- fatalistic Zurvanism.

These are described in the following subsections. Zaehner proposes that each of three arose out of the classical Zurvanism.

Materialist Zurvanism

[edit]Materialist Zurvanism was influenced by the Aristotelian and Empedoclean view of matter, and took "some very queer forms".[12]

While Zoroaster's Ormuzd created the universe with his thought, materialist Zurvanism challenged the concept that anything could be made out of nothing. This challenge was a patently alien idea, discarding core Zoroastrian tenets in favor of the position that the spiritual world – including heaven and hell, reward and punishment – did not exist.

The fundamental division of the material and spiritual is not altogether foreign to the Avesta; Geti and Mainyu (middle Persian: menog) are terms in Mazdaist tradition, where Ahura Mazda is said to have created all first in its spiritual, then later in its material form. But the material Zurvanites redefined menog to suit Aristotelian principles to mean "that which did not (yet) have matter", or alternatively, "that which was still the unformed primal matter". Even this is not necessarily a violation of orthodox Zoroastrian tradition, since the divinity Vayu is present in the middle space between Ormuzd and Ahriman, the void separating the kingdoms of light and darkness.

Ascetic Zurvanism

[edit]Ascetic Zurvanism, which was apparently not as popular as the materialistic kind, viewed Zurvan as undifferentiated Time, which, under the influence of desire, divided into reason (a male principle) and concupiscence (a female principle).

According to Duchesne-Guillemin, this division is "redolent of Gnosticism or – still better – of Indian cosmology". The parallels between Zurvan and Prajapati of Rig Veda 10.129 had been taken by Widengren to be evidence of a proto-Indo-Iranian Zurvan, but these arguments have since been questioned.[8] Nonetheless, there is a semblance of Zurvanite elements in Vedic texts, and, as Zaehner puts it, "Time, for the Indians, is the raw material, the materia prima of all contingent being."

Fatalistic Zurvanism

[edit]The doctrine of Limited Time (allotted to Ahriman by Zurvan) implied that nothing could change this preordained course of the material universe, and the path of the astral bodies of the 'heavenly sphere' was representative of this preordained course. It followed that human destiny must then be decided by the constellations, stars and planets, who were divided between the good (the signs of the Zodiac) and the evil (the planets):

Ohrmazd allotted happiness to man, but if man did not receive it, it was owing to the extortion of these planets.

— Menog-i Khirad 38.4–5[full citation needed]

Fatalistic Zurvanism was evidently influenced by Chaldean astrology and perhaps also by Aristotle's theory of chance and fortune. The fact that Armenian and Syrian commentators translated Zurvan as "Fate" is highly suggestive.

Mistaken identity

[edit]

In his first manuscript of his book Zurvan, Zaehner identified the leontocephalic deity of the Roman Mithraic Mysteries as a representation of Zurvan. Zaehner later acknowledged this mis-identification as a "positive mistake",[16] due to Franz Cumont's late 19th century notion that the Roman cult was "Roman Mazdaism" transmitted to the west by Iranian priests. Mithraic scholars no longer follow this so-called 'continuity theory', but that has not stopped the fallacy (which Zaehner also attributes to Cumont) from proliferating on the Internet.

Negative view of women

[edit]Robert Charles Zaehner mentions that in Zurvanism fire and water are mentioned as male and female and water is considered a dark element and says that Zoroastrian texts in Pahlavi language mention two stories: the first is about women submitting to Ahriman, and the second is a long story about the harlot helping Ahriman fight Ahura Mazda and Keyumars.

After Ohrmazd gave women to righteous men, they fled and submitted to Ahriman; and when Ohrmazd gave righteous men peace and happiness, Ahriman also gave women happiness.” When Ahriman allowed women to ask for whatever they wanted, Ohrmazd feared that they would seek companionship with righteous men and be harmed by it. To prevent this, the god created Narseh (a youth) of fifteen years old. He placed him, naked, behind Ahriman, so that the women would see him, desire him, and ask him for him. The women raised their hands toward Satan and said, “O father Ahriman, give us the god Narseh as a gift.”

'When the Destructive Spirit saw that he himself and the demons were powerless on account of the Righteous Man, he swooned away. For three thousand years he lay in a swoon. And as he lay thus unconscious, the demons with monstrous heads cried out one by one [saying] :"Arise, O our father, for we would join a battle from which Ohrmazd and the Bounteous Immortals will suffer straitness and misery." And one by one they minutely related their own evil deeds. But the accursed Destructive Spirit was not comforted, nor he did arise out of his swoon for fear of the Righteous Man; till the accursed Whore came after the three thousand years had run their course, and she cried out [saying]: "Arise, O our father, for in the battle [to come] I shall let loose so much affliction on the Righteous Man and the toiling Bull that, because of my deeds, they will no be fit to live. I shall take away their dignity (khwarr): I shall afflict the water, I shall afflict the earth, I shall afflict the fire, I shall afflict the plants, I shall afflict all the creation which Ohrmazd has created." And she related her evil deeds so minutely that the Destructive Spirit was comforted, leapt up out of his swoon, and kissed the head of the Whore; and that pollution called menstruation appeared on the Whore. And the Destructive Spirit cried out to the demon Whore: "Whatsoever is thy desire, that do thou ask, that I may give it thee." Then Ohrmazd in his omniscience knew that at that time the Destructive Spirit could give whatever the demon Whore asked and that there would be great profit to him thereby. (The appearance of the body of the Destructive Spirit was in the form of a frog.) And [Ohrmazd] showed one like unto a young man of fifteen years of age to the demon Whore; and the demon Whore fastened her thoughts on him. And the demon Whore cried out to the Destructive Spirit [saying]: "Give me desire for man that I may seat him in the house as my lord." But the Destructive Spirit cried out unto her [saying]: "I do not bid thee ask for anything, for thou knowest [only] to ask for what is profitless and bad." But the time had passed when he could have refused to give what she asked.''[17]

The legacy of Zurvanism

[edit]No evidence of distinctly Zurvanite rituals or practices have been discovered, so followers of the cult are widely believed to have had the same rituals and practices as Mazdean Zoroastrians did. This is understandable, inasmuch as the Zurvanite doctrine of a monist First Principle did not preclude the worship of Ohrmuzd as the Creator (of the good creation). Similarly, no explicitly Zurvanite elements appear to have survived in modern Zoroastrianism.

Dhalla explicitly accepted a modern Western version of the old Zurvanite heresy, according to which Ahura Mazda himself was the hypothetical 'father' of the twin Spirits of Y 30.3 ... Yet though Dhalla thus, under foreign influences, abandoned the fundamental doctrine of the absolute separation of good and evil, his book still breathes the sturdy, unflinching spirit of orthodox Zoroastrian dualism.

— Mary Boyce[18]: 213

Zurvanism begins with a heterodox interpretation of Zarathushtra's Gathas:

Yes, there are two fundamental spirits, twins which are renowned to be in conflict. In thought and in word, in action they are two: the good and the bad.

— Y 30.3 (trans. Insler[full citation needed])

Then shall I speak of the two primal Spirits of existence, of whom the Very Holy thus spoke to the Evil One: "Neither our thoughts nor teachings nor wills, neither or words nor choices nor acts, not our inner selves nor our souls agree."

— Y 45.2[19][page needed]

A literal, anthropomorphic "twin brother" interpretation of these passages gave rise to a need to postulate a father for the postulated literal "brothers". Hence Zurvanism postulated a preceding parent deity that existed above the good and evil of his sons. This was an obvious usurpation of Zoroastrian dualism, a sacrilege against the moral preeminence of Ahura Mazda.[citation needed]

The pessimism evident in fatalistic Zurvanism existed in stark contradiction to the positive moral force of Mazdaism, and was a direct violation of one of Zoroaster's great contributions to religious philosophy: his uncompromising doctrine of free will. In Yasna 30.2 and 45.9, Ahura Mazda "has left to men's wills" to choose between doing good and doing evil. By leaving destiny in the hands of fate (an omnipotent deity), the cult of Zurvan distanced itself from the most sacred of Zoroastrian tenets: that of the efficacy of good thoughts, good words and good deeds.

That the Zurvanite view of creation was an apostasy even for medieval Zoroastrians is apparent from the 10th century Denkard,[6] which in a commentary on Yasna 30.3–5 turns what the Zurvanites considered the words of the prophet into Zoroaster recalling "a proclamation of the Demon of Envy to mankind that Ohrmuzd and Ahriman were two in one womb".[6]: 9.30.4

The fundamental goal of "classical Zurvanism" to bring the doctrine of the "twin spirits" in accord with what was otherwise understood of Zoroaster's teaching may have been excessive, but (according to Zaehner) it was not altogether misguided. In noting the emergence of an overtly dualistic doctrine during the Sasanian period, Zaehner[12] asserted that

[There must] have been a party within the Zoroastrian community which regarded the strict dualism between Truth and the Lie, the Holy Spirit and the Destructive Spirit, as being the essence of the Prophet's message. Otherwise the re-emergence of this strictly dualist form of Zoroastrianism some six centuries after the collapse of the Achaemenian Empire could not be readily explained. There must have been a zealous minority that busied itself with defining what they considered the Prophet's true message to be; there must have been an 'orthodox' party within the 'Church'. This minority, concerned now with theology no less than with ritual, would be found among the Magi, and it is, in fact, to the Magi that Aristotle and other early Greek writers attribute the fully dualist doctrine of two independent principles – Oromasdes and Areimanios. Further, the founder of the Magian order was now said to be Zoroaster himself. The fall of the Achaemenian Empire, however, must have been disastrous for the Zoroastrian religion, and the fact that the Magi were able to retain as much as they did and restore it in a form that was not too strikingly different from the Prophet's original message after the lapse of some 600 years proves their devotion to his memory. It is, indeed, true to say that the Zoroastrian orthodoxy of the Sasanian period is nearer to the spirit of Zoroaster than is the thinly disguised polytheism of the Yashts.[12][page needed]

Thus – according to Zaehner – while the direction that the Sasanians took was not altogether at odds with the spirit of the Gathas, the extreme dualism that accompanied a divinity that was remote and inaccessible made the faith less than attractive. Zurvanism was then truly heretical only in the sense that it weakened the appeal of Zoroastrianism.

Nonetheless, that Zurvanism was the predominant brand of Zoroastrianism during the cataclysmic years just prior to the fall of the empire, is, according to Duchesne-Guillemin, evident in the degree of influence that Zurvanism (but not Mazdaism) would have on the Iranian brand of Shi'a Islam. Writing in the historical present, he notes that "under Chosrau II (r. 590–628) and his successors, all kinds of superstitions tend to overwhelm the Mazdean religion, which gradually disintegrates, thus preparing the triumph of Islam." Thus, "what will survive in popular conscience under the Muslim varnish is not Mazdeism: it is Zervanite fatalism, well attested in Persian literature".[8]: 109 This is also a thought expressed by Zaehner, who observes that Ferdowsi, in his Shahnameh, "expounds views which seem to be an epitome of popular Zervanite doctrine".[3]: 241 Thus, according to Zaehner and Duchesne-Guillemin, Zurvanism's pessimistic fatalism was a formative influence on the Iranian psyche, paving the way (as it were) for the rapid adoption of Shi'a philosophy during the Safavid era.

According to Zaehner[12] and Shaki,[20] in Middle Persian texts of the 9th century, Dahri (from Arabic–Persian dahr, time, eternity) is the appellative term for adherents of the Zurvanite doctrine that the universe derived from Infinite Time.[20]: 35–44 "Dahri" In later Persian and Arabic literature, the term would come to be a derogatory term for 'atheist' or 'materialist'. The term also appears – in conjunction with other terms for skeptics – in Denkard 3.225[6] and in the Skand-gumanig wizar where "one who says god is not, who are called dahari, and consider themselves to be delivered from religious discipline and the toil of performing meritorious deeds".[20]: 587–588

A surviving Zurvanist myth describes him as "both male and female" and the one "god of time" who existed before all other things and gave birth to Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu.[21]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Zurvanism". Encyclopædia Iranica. 28 March 2014. Archived from the original on Apr 10, 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Boyce, Mary (1957). "Some reflections on Zurvanism". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 19 (2). London, UK: School of Oriental and African Studies: 304–316. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00133063. S2CID 161924982.

- ^ a b c d e f g h

Zaehner, R.C. (1955). Zurvan, a Zoroastrian Dilemma (Biblo-Moser ed.). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-8196-0280-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Henning (1951)[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Dhalla (1932)[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d Müller, F.M., ed. (1892). "Denkard 9.30". Sacred Books of the East (SBE). Vol. 37. Translated by West, E.W. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Zādspram" at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ a b c d Duchesne-Guillemin, J. (1956). "Notes on Zurvanism". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 15 (2). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press: 108–112. doi:10.1086/371319. S2CID 162213173.

- ^ Zaehner, R.C. (1940) [1939]. "A Zervanite apocalypse". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 10 (2). London, UK: School of Oriental and African Studies: 377–398. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00087577. S2CID 170841327.

- ^ Nyberg (1931) [full citation needed]

- ^ a b Cumont and Schaeder[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h

Zaehner, R.C. (2003) [1961]. The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism (reprint ed.). New York: Putnam / Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-165-0. "A section of the book is available online". Archived from the original on 2012-05-09.

Several other websites have duplicated this text, but include an "Introduction" section that is very obviously not by Zaehner.

- ^ Boyce (2002)[full citation needed]

- ^ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2025-03-23.

- ^ Vermaseren, Maarten Jozef (1960) [1956]. Corpus inscriptionum et monumentorum religionis mithriacae. 2 vols. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- ^ Zaehner (1972)[full citation needed]

- ^ "Iran Chamber Society: Religion in Iran: Zurvânism". www.iranchamber.com. Retrieved 2025-05-23.

- ^ Boyce, Mary (1979). Zoroastrians, Their Religious Beliefs and Practices.[full citation needed]

- ^ Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism. Translated by Boyce, Mary.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Shaki, Mansour (2002). Encyclopaedia Iranica. New York, NY: Mazda Publications.

- ^ Wilkinson, Philip (1999). Spilling, Michael; Williams, Sophie; Dent, Marion (eds.). Illustrated Dictionary of Religions (First American ed.). New York: DK. p. 21. ISBN 0-7894-4711-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Taraporewala, Irach, ed. (1977). "Yasna 30". The Divine Songs of Zarathushtra. Translated by Bartholomae, Christian. New York, NY: Ams. ISBN 0-404-12802-5.

- "The 'Ulema-i Islam]". The Persian rivayats of Hormazyar Framarz and others. Translated by Dhabhar, Bamanji Nasarvanji. Bombay, IN: K.R. Cama Oriental Institute. 1932.

- Frye, Richard (1959). "Zurvanism Again". The Harvard Theological Review. 52 (2). London, UK: Cambridge University Press: 63–73. doi:10.1017/s0017816000026687. S2CID 248817966.

- Müller, F.M., ed. (1880). "Selections of Zadspram". Sacred Books of the East (SBE). Vol. 5. Translated by West, E.W. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- "The Kartir Inscription". Henning Memorial Volume. Translated by MacKenzie, David Niel. Lund Humphries. 1970. ISBN 0-85331-255-9.

- Zaehner, R.C. (1975). Teachings of the Magi: Compendium of Zoroastrian beliefs. New York, NY: Sheldon. ISBN 0-85969-041-5.

Zurvanism

View on GrokipediaZurvanism was a theological variant within Zoroastrianism that posited Zurvan, the deity embodying infinite time, as the primordial entity whose doubt during a thousand-year sacrifice led to the birth of twin sons: Ohrmazd (Ahura Mazda), the spirit of light and good, and Ahreman (Angra Mainyu), the spirit of darkness and evil.[1] This cosmogony served as a prequel to the standard Zoroastrian creation narrative, introducing a monistic framework where good and evil originate from a single neutral source, contrasting with orthodox Zoroastrian dualism that maintains their independent and eternal opposition.[1] The movement likely emerged in the early Sasanian period (3rd century CE) and reached its height in the 5th century as a court-supported interpretation among Zoroastrian priests, possibly reflecting elite theological speculations rather than widespread popular belief.[1][2] Evidence for Zurvanism derives chiefly from secondary, non-Zoroastrian sources, including polemical accounts by Armenian and Syriac Christian authors like Eznik of Kołb and Ełišē, as well as Greek, Arabic, and later Muslim writings, with scant direct affirmation in Zoroastrian texts such as the Denkard or Bundahišn, which mention Zurvan only peripherally.[1] Scholarly consensus views it as an alternative cosmogony rather than a formal heresy, though debates persist over its prevalence and authenticity, with some arguing it represents a hypothetical construct amplified by hostile external observers rather than a dominant Sasanian orthodoxy.[1] By the 6th century, following the codification of the Avesta and suppression of heterodox movements like Mazdakism, Zurvanism appears to have waned, leaving a legacy primarily in philosophical interpretations of time and causality within Iranian religious thought.[1][2]

Theological Foundations

Core Doctrine and Zurvan as First Principle

Zurvanism elevates Zurvan, conceptualized as zruvan akarana ("infinite time" or "boundless duration" in Avestan-derived terminology), to the status of the ultimate first principle, a neutral and transcendent entity that precedes the dualistic opposition of good and evil.[1] This foundational tenet diverges from orthodox Zoroastrianism by positing Zurvan not as a subordinate abstraction but as the primordial source from which the twin spirits—Ahura Mazda (the principle of light and order) and Angra Mainyu (the principle of darkness and chaos)—emerge as offspring, thereby framing cosmic duality as a secondary development within an overarching temporal framework.[3] In this schema, Zurvan embodies neither benevolence nor malevolence but an impersonal, inexorable process akin to fate or eternity, serving as the causal origin of all existence without inherent moral valuation.[2] The core doctrine manifests in a recurring cosmogonic narrative preserved across Armenian, Greek, and Middle Persian sources, wherein Zurvan undertakes a protracted ritual sacrifice—typically enduring for 1,000 years—to engender a singular progeny capable of world-creation.[4] Doubt or impatience intrudes during this rite, prompting Zurvan to vow that if a female child results from his spilled seed, it would unite with him, or if male, it would rule; this ambivalence yields twins, with Ahura Mazda bursting forth from Zurvan's side or armpit (symbolizing purity) and Angra Mainyu from the womb or buttocks (denoting impurity).[1] Despite their fraternal origin, the twins embody irreconcilable essences—good by nature in Mazda, evil in Mainyu—though Zurvan's pact grants the destructive spirit temporary dominion over the material world for 9,000 years before ultimate rectification.[5] This myth underscores Zurvan's role as the unmotivated generator of duality, where time's infinity neutralizes ethical primacy, introducing fatalistic undertones absent in traditions prioritizing Ahura Mazda's uncreated sovereignty.[6] Philosophically, Zurvan functions as a supersubstantival substrate, with the universe's matter and events unfolding as modalities of infinite time rather than autonomous creations of a willful deity.[2] Proponents viewed this as resolving the "problem of evil" by subordinating moral conflict to temporal necessity, though it rendered Ahura Mazda non-omnipotent, as his victory depends on Zurvan-ordained chronology rather than intrinsic supremacy.[5] Theological texts distinguish zurvan akarana (infinite, acausal time) from zurvan derang (finite, measured time), the former as the eternal first principle and the latter as its manifested derivative, aligning Zurvanism with a deterministic ontology where human agency intersects predestined cycles.[1] This framework, while influential in Sasanian-era speculations (circa 224–651 CE), drew critique from orthodox sources for diluting divine wisdom in favor of mechanistic inevitability.[3]Distinctions from Orthodox Zoroastrianism

In Zurvanism, Zurvan—personified as infinite Time—serves as the uncreated first principle and supreme deity, who through a thousand-year sacrifice and subsequent doubt begets the twin spirits Ohrmazd (Ahura Mazda) and Ahriman (Angra Mainyu) from divided semen, positioning duality as derivative from a neutral, singular origin.[7][2] This contrasts sharply with orthodox Zoroastrianism, where Ahura Mazda stands as the self-existent, uncreated Wise Lord and sole creator of all beneficent order, without subordination to a higher entity or reliance on a sacrificial act marred by doubt.[7][8] Consequently, Zurvanism subordinates Ahura Mazda to a paternal role under Zurvan, rendering the good spirit one of two co-engendered divinities, whereas orthodoxy upholds Ahura Mazda's supremacy and independence, with Ahriman as an adversarial force rather than a fraternal twin.[2][8] The cosmogonic myth in Zurvanism further diverges by attributing the material world's creation to Zurvan's decree, establishing a predetermined cosmic timeline wherein Ahriman gains temporary dominion over the world for 9,000 years due to Zurvan's binding promise, thus embedding fatalism into the ontology of time as an inexorable arbiter.[7][8] Orthodox Zoroastrianism, by contrast, frames creation as Ahura Mazda's willful act of spiritual and material order (asha), invaded by Ahriman's independent choice of destruction, emphasizing moral agency and the ultimate triumph of good without a neutral temporal sovereign dictating outcomes.[7][2] This introduces in Zurvanism a supersubstantival view where time encompasses and substantiates all processes, reducing divine action to stretches within Zurvan's infinity, opposed to orthodoxy's focus on Ahura Mazda's ethical dualism unmediated by deified time.[2] These differences engendered tensions, with Zurvanism often labeled a heresy in Pahlavi texts for diluting Ahura Mazda's unalloyed goodness and introducing materialist or deterministic strains that orthodox doctrine condemned as incompatible with Zoroaster's emphasis on free choice between truth and lie.[7][8] While Zurvanism preserved Zoroastrian ritual and ethical binaries, its prioritization of Zurvan elevated a neutral eternity over the moral primacy of Ahura Mazda, fostering philosophical speculation on evil's origins that orthodoxy resolved through eternal opposition rather than unified parentage.[2][7]Historical Origins and Evidence

Primary Sources and Archaeological Traces

The earliest textual reference to Zurvan appears in the History of Theology attributed to Eudemus of Rhodes (c. 370–300 BCE), who described Persian beliefs positing three primordial principles: time (identified with Zurvan), light (Oromasdes, or Ahura Mazda), and darkness (Areimanios, or Angra Mainyu), with the twins emerging from time as a unifying source.[9] This Greek account, preserved through later citations like Damascius, represents the oldest external evidence but relies on second-hand reporting of Achaemenid-era Iranian cosmology, potentially influenced by Hellenistic interpretations.[1] Subsequent non-Zoroastrian sources from the Sasanian period provide more detailed cosmogonic myths. The Armenian theologian Eznik of Kolb (5th century CE), in his polemical Refutation of Sects, critiqued what he termed a Persian heresy wherein Zurvan, as infinite time, sacrificed for a thousand years to produce a son but, gripped by doubt, inadvertently birthed twins—Ohrmazd (good) from semen on his arm and Ahriman (evil) from menstruation—granting Ahriman a pact for temporary dominion.[10] Similarly, the Syriac scholar Theodore bar Konai (8th century CE) recorded a variant myth in his Book of Scholia, attributing to magi the view of Zurvan as a neutral progenitor of the dual principles, with Ahriman's aggression stemming from envy after Ohrmazd's favored creation of the world.[5] Arabic authors like al-Shahrastani (d. 1153 CE) echoed these narratives, framing Zurvanism as a fatalistic sect among Zoroastrians, though filtered through Islamic theological lenses.[1] Manichaean texts, such as Mani's Shabuhragan (3rd century CE), equated Zurvan with the Father of Greatness, suggesting early Sasanian syncretism, but these derive from a rival faith hostile to orthodox Zoroastrianism.[1] Zoroastrian Pahlavi texts offer indirect traces rather than explicit doctrine. The Denkard (9th–10th century CE compilation) portrays Zurvan as "infinite time" in cosmological stages—becoming, mixture, separation, and permanence—without elevating it to supremacy, while the Selections of Zadspram (9th century) depicts Zurvan as an arbiter imposing a pact between Ohrmazd and Ahriman, hinting at neutralism but aligning with dualist orthodoxy.[5] The Bundahishn briefly lists Zurvan among deities, and Menog-i Khrad invokes its blessing on creation, yet later orthodox works like Shkand-gumanik Vichar explicitly oppose Zurvanite fatalism as deviant.[5] These Middle Persian references, redacted post-Sasanian conquest, show conceptual integration of time but no sectarian endorsement, leading scholars to debate whether they reflect purged Zurvanite influences or mere metaphorical usage.[1] Archaeological traces remain scant and interpretive. The 1st-century BCE inscriptions of Antiochus I of Commagene invoke chronos apeiros ("boundless time") alongside Iranian deities, speculated by some to reflect Zurvanite syncretism in a Hellenistic-Iranian context, though direct linkage is tenuous.[1] No Sasanian-era temples, seals, or reliefs unequivocally depict Zurvan as a supreme figure; orthodox iconography favors Ahura Mazda, with Zurvan's role confined to abstract temporal motifs in texts rather than material cult objects.[9] This paucity underscores reliance on textual polemics from external, often adversarial sources, rendering Zurvanism's prevalence hypothetical absent confirmatory artifacts.[1]Scholarly Debates on the Extent of Zurvanism

R. C. Zaehner, in his 1955 work Zurvan: A Zoroastrian Dilemma, posited that Zurvanism constituted the prevailing theological framework among Sasanian Zoroastrian clergy and possibly the state doctrine during the early Sasanian period (circa 224–651 CE), drawing on Armenian, Syriac, and Greek sources that depict Zurvan as the primordial entity from which Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu emanated.[11] He argued this based on references in texts like Eznik of Kolb's Refutation of the Sects (5th century CE), which describe Zurvanite cosmogony as normative among Persians, and Manichaean fragments portraying Zurvan (as Zurwan or *Zurvakan) in a supratemporal role.[1] Subsequent scholars, including Mary Boyce, challenged Zaehner's assessment of Zurvanism's dominance, contending in her 1968 article "Some Further Reflections on Zurvanism" that it represented a philosophical heresy rather than a widespread orthodoxy, confined largely to speculative priestly circles and lacking endorsement in core Pahlavi texts like the Denkard (9th century CE compilation), which explicitly condemns Zurvanite fatalism as deviant.[12] Boyce emphasized the scarcity of direct epigraphic evidence, noting that Sasanian inscriptions, such as those of high priest Kartir (late 3rd century CE), invoke Zurvan alongside Ahura Mazda in a subordinate capacity as "boundless time" (zurvan akarana) without elevating it to a monistic first principle, suggesting regional or interpretive variations rather than systemic adoption.[9] Further critiques, advanced by Gherardo Gnoli and Shaul Shaked in the late 20th century, highlight the interpretive overreach in reconstructing Zurvanism from adversarial non-Zoroastrian sources—such as Theodore bar Konai's 8th-century Syriac Scholia—which may exaggerate its prevalence to underscore orthodox dualism's triumph.[1] These scholars point to the absence of distinct Zurvanite rituals, temples, or iconography in archaeological records from Sasanian sites like Naqsh-e Rostam, arguing that purported evidence often stems from Hellenistic influences or Manichaean adaptations rather than indigenous mass belief.[4] Contemporary consensus, as reflected in syntheses like the Encyclopaedia Iranica (2014 update), leans toward Zurvanism as an influential but marginal strain, potentially prominent at the Sasanian court under rulers like Shapur I (r. 240–270 CE) due to exposure to Greek and Indian fatalistic ideas, yet ultimately subordinated to Ahura Mazda-centric orthodoxy by the 5th century CE amid mobeds' (priests') efforts to codify texts against it.[1] This view accounts for textual survivals in heresiological polemics, which indicate debate but not ubiquity, with empirical traces limited to linguistic epithets rather than doctrinal hegemony.[13]Cosmogonic Myths and Variants

The Twin Brothers Creation Narrative

In the Zurvanite cosmogonic myth, Zurvan, conceptualized as infinite time and the primordial deity, performs sacrifices for one thousand years in order to produce a son who would create the world.[14] During this prolonged rite, as the period approached its conclusion, Zurvan experienced a momentary doubt regarding the efficacy of his sacrifices.[14] This doubt resulted in the conception of twin sons within Zurvan's womb: Ohrmazd (Ahura Mazda), emerging from the positive essence of the sacrifices and embodying goodness and light, and Ahriman (Angra Mainyu), arising from the doubt and representing evil and darkness.[14] The twins, antagonistic from inception, contended within the womb, with Ohrmazd perceiving the spiritual realm and discerning good from evil, while Ahriman detected only material corruption and malice.[14] Aware of their conflict, Zurvan decreed that the first-born son would receive sovereignty over the creation.[14] Intending this dominion for Ohrmazd, Zurvan nonetheless bound himself to the oath; Ahriman, cunningly aware of the promise, forcibly tore through the womb to emerge first, thereby claiming the right to rule.[14] Reluctantly honoring the vow, Zurvan granted Ahriman temporary dominion over the material world for nine thousand years, after which Ohrmazd would ultimately prevail and restore order, confining Ahriman to defeat.[14] This narrative underscores Zurvan's neutrality as a higher principle beyond good and evil, with the twins' opposition predestined yet resolved in favor of good through temporal limitation.[14] The myth survives primarily in non-Zoroastrian heresiological accounts, such as the fifth-century Armenian Christian text Refutation of the Sects by Eznik of Kolb, who critiques it as a Persian doctrine, alongside Syriac, Greek, and Arabic sources; no direct Zoroastrian texts endorse it, suggesting its transmission through polemical filters.[14] [15] Variants exist in the precise mechanism of the twins' origins, but the core elements of sacrifice, doubt, and fraternal rivalry remain consistent across attestations.[14]Alternative Interpretations of Zurvan's Role

In certain renditions of Zurvanite cosmogony, Zurvan functions not merely as the sacrificial progenitor of twin spirits but as an androgynous entity whose essence directly materializes the cosmos, encompassing both paternal and maternal attributes in the generative act. This interpretation, preserved in Armenian theological critiques like those of Eznik of Kolb (5th century CE), posits that Zurvan's prolonged sacrifice yields a seminal essence that first forms a female figure—often linked to a covenant or intermediary deity—before the antagonistic twins emerge through Ahriman's violent self-extraction from the womb, thereby emphasizing Zurvan's role as a bisexual origin rather than a strictly paternal one.[1] Such a depiction underscores a mythic mechanism where gender duality precedes ethical opposition, diverging from orthodox Zoroastrian primacy of moral spirits.[4] Alternative scholarly reconstructions highlight Zurvan as a transcendental neutral principle, unbound by ethical valuation, who oversees the dualistic conflict as an impartial arbiter of infinite time and fate, rather than an active originator tainted by doubt. In this framework, drawn from Pahlavi and Manichaean-influenced texts, Zurvan precedes and encompasses Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu as emanations or sons without implying Zurvan's moral ambiguity; instead, the deity embodies boundless duration (zorvan akarana), ensuring the predetermined resolution of cosmic struggle after 9,000 years, thus prioritizing temporal inevitability over volitional creation.[9] This neutral Zurvan contrasts with dualistic Zoroastrianism's unoriginated good, as critiqued in later orthodox sources for subordinating ethical agency to mechanistic eternity.[8] Some variants, particularly in materialist strains of Zurvanism, reframe Zurvan's role as the substantival substrate of space, time, and matter, from which the twins arise dialectically without a sacrificial narrative, positioning Zurvan as the undifferentiated "all" that fragments into opposition. This interpretation, inferred from Sassanian-era philosophical texts and later exegeses, aligns Zurvan with a pre-dualistic totality, where creation emerges from inherent contradiction rather than ritual intent, potentially reflecting influences from Mesopotamian or Hellenistic cosmologies.[2] However, primary evidence remains fragmentary, with such views often reconstructed from polemical accounts by Armenian and Syriac authors who attribute monistic tendencies to Zurvanites, though these may exaggerate to highlight deviations from Zoroaster's teachings.[16]Types and Philosophical Strains

Materialist and Ascetic Forms

Materialist Zurvanism, often linked to the heretical Zandiks sect, conceived of Zurvan as infinite space-time from which all creation emanated materially, without intervention by a transcendent creator god or ethical dualism.[5][17] This strand rejected core Zoroastrian elements such as heaven, hell, posthumous rewards, and spiritual resurrection, positing instead an eternal, self-sustaining cosmos akin to dialectical materialism.[5] Influenced by Aristotelian notions of prime matter and possibly Empedoclean cosmology, as well as Indian concepts from texts like the Maitri Upanishad, it diverged sharply from orthodox Zoroastrianism's emphasis on Ahura Mazda's willed creation ex nihilo.[5] Scholar R. C. Zaehner described this form as uncharacteristic of Iranian religious traditions, viewing it as a philosophical import that undermined ethical accountability and free will.[18] Ascetic Zurvanism, less prevalent than its materialist counterpart, portrayed Zurvan as primordial undifferentiated time that, compelled by desire or doubt, fractionated into opposing principles of reason (associated with the good, Ohrmazd) and concupiscence or lust (linked to evil, Ahriman).[18] This cosmogonic split engendered a pessimistic ontology, deeming the material world a flawed product of base impulses and thus warranting ascetic renunciation over worldly engagement.[5] Zaehner identified this ethical variant as fostering an ascetic orientation atypical of Zoroastrianism, which affirmed life's goodness and ritual participation rather than withdrawal or world-denial.[18] Drawing from Pahlavi texts like the Selections of Zādspram, it retained some dualistic tension but subordinated it to Zurvan's neutral eternity, potentially aligning with fatalistic undertones that diminished human agency.[5] While Zaehner attributed these traits to broader Zurvanite tendencies, later scholars such as Mary Boyce contested the prominence of such ascetic strains, arguing they represented marginal innovations rather than dominant Sasanian practice.[18]Fatalistic Elements and Their Implications

In Zurvanite cosmogony, fatalistic elements arise from the foundational myth wherein Zurvan, doubting the efficacy of his prolonged sacrifice, inadvertently engenders both Ohrmazd (the principle of light and good) and Ahreman (the principle of darkness and evil) as twin offspring, with their rivalry and the cosmic struggle predetermined by Zurvan's prior pact to grant dominion to the firstborn.[1] This narrative, preserved in Armenian, Syriac, and Greek sources dating to the Sasanian period (circa 224–651 CE), posits that the sequence of creation and conflict stems from Zurvan's own temporal limitations rather than independent moral agency, rendering the dualistic opposition inevitable.[1] Zurvan's identification as infinite Time (Zūrvān akaranā) further reinforces determinism, portraying the deity as an impartial arbiter whose essence encompasses boundless duration, within which all events—including human actions and eschatological outcomes—unfold inexorably, independent of ethical striving.[1] Scholar R.C. Zaehner describes Zurvan in this strain as the "God of Fate," a neutral force dyed with both good and evil, subordinating the powers of Ohrmazd and Ahreman to temporal mechanics and thereby diminishing divine volition to mere participants in a preordained cycle.[19] This view echoes Babylonian astrological influences, where celestial patterns dictate terrestrial affairs, introducing a mechanistic predestination alien to core Zoroastrian tenets.[20] The implications of such fatalism profoundly challenged orthodox Zoroastrianism's emphasis on human free will and active choice in the cosmic battle between good and evil, as articulated in Avestan texts like the Gathas, where individuals bear responsibility for aligning with asha (truth/order) through deliberate deeds.[1] By attributing salvation to the inexorable workings of fate rather than personal merit or ritual efficacy, Zurvanism risked fostering ethical passivity, with adherents potentially viewing adversity as unalterable destiny rather than a call to moral exertion.[21] Orthodox critiques, exemplified by Sasanian priest Aturpat i Mahrspend (fl. 3rd–4th century CE), confined fate's influence to mundane aspects like lifespan or wealth—limiting it to five of twenty-five existential factors—while insisting that spiritual progress depends on individual resolve and good thoughts, words, and deeds.[20] This tension contributed to Zurvanism's marginalization, as its deterministic framework undermined the religion's motivational core, prompting accusations of heresy for eroding the dualistic imperative of free moral combat against Angra Mainyu.[1] Zaehner contends that extreme fatalism, incompatible with Zoroastrian sanity and resilience in misfortune, likely permeated the tradition via Zurvanite channels but was ultimately rejected in favor of an activism-preserving orthodoxy.[20] Scholarly assessments, including those by Shaul Shaked, frame these elements not as a unified sect's dogma but as interpretive variants within broader Zoroastrian discourse, though their deterministic leanings highlight ongoing philosophical friction over agency versus inevitability.[1]Historical Trajectory

Emergence in Pre-Sasanian Periods

The concept of Zurvan, denoting "time," first emerges in the Avesta, Zoroastrianism's foundational texts composed orally between approximately 1500 and 500 BCE, where it functions primarily as an abstract principle of infinite duration rather than a supreme deity. In Yasna 45.2, for instance, it appears as zruuānąm akaranąm, or "boundless time," invoked in a cosmological context without implying paternity over divine twins Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu. Similarly, in later Avestan sections like the Yashts, Zurvan is occasionally personified as a minor yazata (beneficent spirit) associated with oaths and fate, but lacks the hierarchical supremacy characteristic of mature Zurvanism. These references suggest an early Iranian conceptualization of time as eternal and impersonal, potentially rooted in Indo-Iranian traditions, though they do not constitute a systematic theology elevating Zurvan above Ohrmazd (Ahura Mazda).[22] By the late Achaemenid period (c. 550–330 BCE), Greek observers reported more developed Zurvanite-like ideas among Persian Magi. Eudemus of Rhodes (c. 370–300 BCE), in his History of Theology, describes a Persian doctrine wherein Time (Chronos, equated with Zurvan) generates the principles of light (Oromasdes, i.e., Ahura Mazda) and darkness (Areimanios, i.e., Angra Mainyu) as primordial offspring, followed by their creation of further divinities. This account, preserved through later Neoplatonist citations like Damascius, represents the earliest external attestation of a Zurvanite cosmogony, implying its circulation in western Iranian elite circles during the empire's final centuries. However, scholars caution that Eudemus's interpretation may reflect Hellenistic philosophical lenses projecting Greek notions of boundless time onto Iranian beliefs, rather than verbatim Magian doctrine, as no corroborating Achaemenid inscriptions or artifacts explicitly endorse Zurvan's supremacy.[22][12] In the subsequent Parthian (Arsacid) era (247 BCE–224 CE), Zurvanism likely gained traction amid cultural syncretism with Hellenistic influences, though direct evidence remains elusive. Historical analyses posit that exposure to Greek Chronos and Babylonian astral fatalism during Parthian cosmopolitanism fostered materialist strains emphasizing time's deterministic oversight of cosmic struggle, potentially bridging Avestan abstractions to Sasanian formulations. Armenian and Syriac sources from this period allude to divergent Zoroastrian sects, but without naming Zurvanism explicitly; instead, they highlight theological tensions over fate versus free will that align with proto-Zurvanite motifs. The scarcity of indigenous Parthian texts precludes firm attribution, leading experts to view this phase as preparatory rather than definitive for Zurvanism's institutional emergence.[4]Prominence and State Support in Sasanian Era

Zurvanism attained significant prominence within Sasanian court and priestly circles during the 5th century CE, emerging as a variant cosmogony that interpreted Zoroastrian creation myths through Zurvan as the primordial source of the twin spirits, Ohrmazd and Ahreman. This theological framework likely originated among early Sasanian court priests, drawing on interpretations of Yasna 30.3, and gained traction as a means to reconcile dualistic elements under a unifying temporal principle. Evidence from non-Zoroastrian sources, including Armenian and Syriac texts, attests to its influence, though it remains absent from canonical Zoroastrian literature, suggesting it functioned as an elite interpretive tradition rather than a mass doctrine.[14] State support manifested indirectly through high-ranking officials rather than explicit royal endorsement or imposition as official orthodoxy. The wuzurg-framādār Mihr-Narseh, serving under Yazdegerd II (r. 438–457 CE) from circa 421–439 CE, invoked the Zurvan myth in official correspondence urging Zoroastrian conversion among Armenians, framing it as a rationale for religious unity ahead of the Battle of Avarayr in 451 CE. This usage indicates court-level acceptance and deployment in imperial religious policy, corroborated by Armenian accounts such as Ełišē's History of Vardan. However, no Sasanian inscriptions or Zoroastrian texts affirm Zurvanism as state doctrine; high priests like Kerdir (3rd century CE) emphasized orthodox Mazdaean purity without reference to it, implying selective elite patronage amid broader promotion of standardized Zoroastrianism.[14] [23] Modern scholarship, including analyses by Shaul Shaked, rejects earlier claims—such as those by Arthur Christensen positing Zurvanism as the dominant Sasanian religion—as overstated, viewing it instead as a non-sectarian cosmogonic option influential at court but not universally enforced or heretical in its era. Manichaean texts like the Šābuhragān (early Sasanian) reflect awareness of Zurvanite elements, likely in polemic or adaptation, underscoring its cultural visibility without evidencing widespread institutional backing. This limited prominence waned with later orthodox revivals, as Pahlavi compilations favored dualistic primacy over Zurvan's neutral paternity.[14]