Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

| Millennia |

|---|

| 1st millennium |

| Centuries |

| Decades |

| Years |

|

| Categories |

The 0s began on January 1, AD 1 and ended on December 31, AD 9, covering the first nine years of the Common Era.

In Europe, the 0s saw the continuation of conflict between the Roman Empire and Germanic tribes in the Early Imperial campaigns in Germania. Vinicius, Tiberius and Varus led Roman forces in multiple punitive campaigns, before sustaining a major defeat at the hands of Arminius in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Concurrently, the Roman Empire fought the Bellum Batonianum against a rebelling alliance of native peoples led by Bato the Daesitiate in Illyricum, which was suppressed in AD 9. A conflict also took place in Korea, where Daeso, King of Dongbuyeo invaded Goguryeo with a 50,000-man army in AD 6. He was forced to retreat when heavy snow began to fall, stopping the conflict until the next decade. In China, the last ruler of the Chinese Western Han dynasty (Ruzi Ying) was deposed, allowing Wang Mang to establish the Xin dynasty.

Literary works from the 0s include works from the ancient Roman poet Ovid; the Ars Amatoria, an instructional elegy series in three books, Metamorphoses, a poem which chronicles the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar within a loose mythico-historical framework, and Ibis, a curse poem written during his years in exile across the Black Sea for an offense against Augustus. Nicolaus of Damascus wrote the 15-volume History of the World.

Estimates for the world population by AD 1 range from 170 to 300 million. A census was concluded in China in AD 2: final numbers showed a population of nearly 60 million (59,594,978 people in slightly more than 12 million households). The census is one of the most accurate surveys in Chinese history.

Calendar details

[edit]Because there is no year zero in the Gregorian calendar, this period is one of two "1-to-9" decade-like timespans that contain only nine years, along with the 0s BC. The Anno Domini (AD) calendar era which numbers these years 1-9 was devised by Dionysius Exiguus in 525, and became widely used in Christian Europe in the 9th century. Dionysius assigned BC 1 to be the year he believed Jesus was born (or according to at least one scholar, AD 1).[2][3] Modern scholars disagree with Dionysius' calculations, placing the event several years earlier (see Chronology of Jesus).

Errors applying leap years in the Julian Calendar affect parts of this 1-to-9 timespan. As a result, sources differ as to whether, for example, AD 1 was a common year starting on Saturday or Sunday. It was a common year starting on Saturday by the proleptic Julian calendar, and a common year starting on Monday by the proleptic Gregorian calendar. It is the epoch year for the Anno Domini (AD) Christian calendar era, and the 1st year of the 1st century and 1st millennium of the Christian or Common Era (CE).

Politics and wars

[edit]

Heads of state

[edit]For brevity, only the most powerful and hegemonic states of the period are included. See list of state leaders in the 1st century for a broader list. Furthermore, the last year of a reign is excluded from this table if it lasted multiple years.

| Polity | AD 1 | AD 2 | AD 3 | AD 4 | AD 5 | AD 6 | AD 7 | AD 8 | AD 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roman Empire | Augustus | ||||||||

| Chinese Empire | Ping | Ruzi Ying | Wang Mang | ||||||

| Parthian Empire[4] | Phraates IV | Phraates V and Musa | (none) | Orodes III | (none) | Vonones I | |||

Wars

[edit]| Start | Finish | Name of Conflict | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 AD | 9 AD | Bellum Batonianum | |

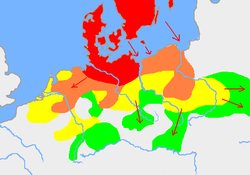

| 12 BC | AD 16 | Early imperial campaigns in Germania | By AD 1, the Roman Empire had been expanding its territories and exerting influence throughout Europe, including regions bordering the Rhine River. The Romans sought to consolidate their control over Germanic territories east of the Rhine and integrate them into the empire. Between 2 BC and AD 4, Vinicius commanded five legions in Germany, successfully leading them in the "vast war" against Germanic tribes. He was awarded the ornamenta triumphalia upon his return to Rome. In AD 4, Tiberius took command and waged campaigns in northern Germany, conquering several tribes and establishing alliances. The Cherusci tribe, including the influential Arminius, became friends with Rome. Tiberius built a winter base on the Lippe to monitor the Cherusci. By AD 6, most German tribes were pacified, and Rome planned an attack on the Marcomanni but made peace instead. Varus replaced Tiberius and imposed civic changes, but Arminius incited a revolt. In AD 9, Varus fell into an ambush by Arminius, suffering a devastating defeat as Roman forces were surrounded and overwhelmed. Varus took his own life, while a few survivors managed to return to Roman quarters. |

| 6 AD | 21 AD | Goguryeo-Dongbuyeo Wars |

Events

[edit]

Africa

[edit]- AD 2 – Juba II of Mauretania joins Gaius Caesar in Armenia as a military advisor. It is during this period that he meets Glaphyra, a Cappadocian princess and the former wife of Alexandros of Judea, a brother of Herod Archelaus, ethnarch of Judea, and becomes enamoured with her.[5]

- AD 7 – The epoch of the Ethiopian calendar begins.

China

[edit]- AD 1 – Confucius is given his first royal title (posthumous name) of Baocheng Xuan Ni Gong.[6][7]

- AD 2 – Wang Mang begins a program of personal aggrandizement, restoring marquess titles to past imperial princes and introducing a pension system for retired officials. Restrictions are placed on the Emperor's mother, Consort Wei and members of the Wei Clan.[8]

- AD 2 – The first census is concluded in China after having begun the year before: final numbers show a population of nearly 60 million (59,594,978 people in slightly more than 12 million households). The census is one of the most accurate surveys in Chinese history.[8]

- AD 3 – Wang Mang foils a plot by his son, Wang Yu, his brother-in-law, Lu Kuan, and the Wei clan to oust him from the regent's position. Wang Yu and Lu Kuan are killed in the purge that follows.[9]

- AD 4 – Emperor Ping of Han marries Empress Wang (Ping), daughter of Wang Mang, cementing his influence.

- AD 4 – Wang Mang is given the title "superior duke".[10]: 64

- AD 6, January – Some Chinese fear for the life of the young, ailing Emperor Ping Di as the planet Mars disappears behind the moon this month.[10]

- AD 6, February 3 – The boy emperor, Ping Di, dies of unexpected causes at age 14; Wang Mang alone selects the new emperor, Ruzi Ying, age 2,[10] starting the Jushe era of the Han dynasty.

- AD 6 – Candidates for government office must take civil-service examinations.

- AD 6 – The imperial Liu clan suspects the intentions of Wang Mang and foment agrarian rebellions during the course of Ruzi Ying's reign. The first of these is led by Liu Chong, Marquess of Ang-Zong (a/k/a Marquis of An-chung), with a small force starting in May or June.[10]

- AD 7 – Zhai Yi, Governor of the Commandery of Dong (modern Puyang, Henan) declares Liu Zin, Marquess of Yang Xiang (modern Tai'an, Shandong), emperor. This proves to be the largest of the rebellions against Emperor Ruzi of Han.

- AD 7 – Wang Mang puts down the rebellion during the winter. Zhai is captured and executed while Liu Xin escapes.

- AD 8 – Start of Chushi era of the Chinese Han dynasty.

- AD 8 – Wang Mang crushes a rebellion by Chai I, and on the winter solstice (which has been dated January 10 of the following year) officially assumes the title emperor, establishing the short-lived Xin dynasty.[10]

- AD 9, January 10 – Wang Mang founds the short-lived Xin dynasty in China (until AD 25). Wang Mang names his wife, Wang, empress and his son, Wang Lin Crown Prince, heir to the throne.[citation needed]

- AD 9 – Empress Wang is given the title of Duchess Dowager of Ding'an, while Ruzi Ying, the former Emperor of Han, becomes the Duke of Ding'an. Ruzi Ying is placed under house arrest.[citation needed]

Europe

[edit]- AD 8 – Tincomarus, deposed king of the Atrebates, flees Britain for Rome; Eppillus becomes king.

Korea

[edit]- AD 4 – Namhae Chachaung succeeds Bak Hyeokgeose as king of the Korean kingdom of Silla (traditional date).

Persia

[edit]- AD 2 - Vonones I, who had been installed as king of the Parthian Empire after a period of exile in Rome, was deposed by the Mahestan, the Parthian noble council. His Romanized policies and mannerisms were unpopular among the Parthian aristocracy, prompting the council to replace him with Artabanus III, a more traditional Parthian ruler.[11]

- AD 4 – King Phraataces and Queen Musa of Parthia are overthrown and killed, the crown being offered to Orodes III of Parthia—the beginning of the interregnum.

- AD 7 – Vonones I becomes ruler of the Parthian Empire (approximate date).

- AD 8 – Vonones I becomes king (shah) of the Parthian Empire.

Roman Empire

[edit]- AD 1 – Tiberius, under order of Emperor Augustus, quells revolts in Germania (AD 1–5).[12]

- AD 1 – Gaius Caesar meets with Phraates V, the king of Parthia, on the Euphrates. Rather than invade the Parthians, Gaius Caesar concludes peace with them; Parthia recognizes Roman claims to Armenia.[13]

- AD 1 – Birth of Jesus, as assigned by Dionysius Exiguus in his anno Domini era according to at least one scholar.[2][3] However, most scholars think that Dionysius placed the birth of Jesus in the previous year, 1 BC.[2][3] Furthermore, most modern scholars do not consider Dionysius' calculations authoritative, placing the event several years earlier (see Chronology of Jesus).[14]

- AD 2 – Following the death of Lucius Caesar, Augustus allows his stepson Tiberius back into Rome as a private citizen, after six years of enforced retirement on Rhodes.[15]

- AD 3 – The rule of Emperor Augustus is renewed for a ten-year period.[16]

- AD 4 – Emperor Augustus summons Tiberius to Rome, and names him his heir and future emperor. At the same time, Agrippa Postumus, the last son of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, is also adopted and named as Augustus' heir.

- AD 4 – Tiberius also adopts Germanicus as his own heir.

- AD 4 – The Lex Aelia Sentia regulates the manumission of slaves.

- AD 4 – A pact of non-aggression and friendship is signed between the Roman Empire, represented by Tiberius, and the German tribe the Cherusci, represented by their King Segimer. Arminius and Flavus, sons of Segimer, are brought into the Roman army as leaders of the auxiliary troops.

- AD 4 – Julia the Elder returns from exile to live in Rhegium in disgrace.

- AD 4 – Livilla marries Drusus Julius Caesar, son of Tiberius.

- AD 4 – Nicolaus of Damascus writes the 15-volume History of the World.

- AD 5 – Rome acknowledges Cunobelinus, king of the Catuvellauni, as king of Britain.

- AD 5 – The Germanic tribes of Cimbri and Charydes send ambassadors to Rome.

- AD 5 – Tiberius conquers Germania Inferior.

- AD 5 – Agrippina the Elder marries Germanicus, her second cousin.

- AD 6 – Due to a catastrophic fire in Rome, the barracks system - the vigiles, initially manned only by freedmen - is created by the Princeps Augustus to allow quicker response to outbreaks of fire in the city.[17]

- AD 6 – Due to a food shortage in Rome, Augustus doubles the grain rations distributed to the people, sends away his slave retinue, and places the senate in recess indefinitely.[18]

- AD 6 – The Princeps Augustus sets up a treasury, the aerarium militare (170 million sestertii), with the specific purpose of paying bonuses to retiring legion veterans. This is financed by a 5% tax on inheritances, a system said to have been suggested in Julius Caesar's memoirs.[19]

- AD 6 – The Temple of Castor and Pollux is rededicated in Rome by Tiberius after being destroyed by fire in 14 BC.[20]

- AD 6 – A pamphletting campaign in Rome is quashed by the Princeps Augustus. Publius Plautius Rufus is accused but found innocent of the crime.[21]

- AD 6 – Princeps Augustus banishes Agrippa Postumus, one of his adopted sons, to the island of Planasia.

- AD 6 – Tiberius makes Carnuntum his base of operations against Maroboduus; The Roman legion XX Valeria Victrix fight with Tiberius against the Marcomanni.[22]

- AD 6 – The building of a Roman fort signifies the origin of the city of Wiesbaden.

- AD 6 – The Illyrian tribes in Dalmatia and Pannonia revolt and begin the Bellum Batonianum or Great Illyrian Revolt.[22][23]

- AD 6 – Troops are levied in Rome to send to Illyricum from freedmen and slaves freed specifically for the purpose.[23]

- AD 6 – Tiberius marches back from the northern border to Illyricum to commence operations against the Illyrians.[24][25]

- AD 6 – Gaius Caecina Severus is made governor of Moesia, and is heavily involved in the first battles of the Bellum Batonianum or Great Illyrian Revolt.[26][27]

- AD 6 – Marcus Plautius Silvanus is made governor of Galatia and Pamphylia and suppresses an uprising of the Isaurians in Pamphylia.[28]

- AD 6 – Herod Archelaus, ethnarch of Samaria, Judea, and Idumea, is deposed and banished to Vienne in Gaul.[21]

- AD 6 – Iudaea and Moesia become Roman provinces.

- AD 6 – Quirinius conducts a census in Judea (according to Josephus), which results in a revolt in the province, led by Judas of Galilee, and supported by the Pharisee Zadok. The revolt is repressed, and the rebels are crucified, but it results in the birth of the Zealot movement, the members of which regard the God of Judaism as their only master.

- AD 7 – Illyrian tribes in Pannonia and Dalmatia continue the Great Illyrian Revolt against Roman rule.[29]

- AD 7 – Publius Quinctilius Varus is appointed governor of Germania, charged with organizing Germania between the Rhine and Elbe rivers. He carries out a census, devises tributes and recruits soldiers, all of which creates dissension among the Germanic tribes.

- AD 7 – Abgarus of Edessa is deposed as king of Osroene.

- AD 7 – Construction of the Temple of Concord begins.

- AD 8, August 3 – Roman general Tiberius defeats the Illyrians in Dalmatia on the River Bathinus, but the Great Illyrian Revolt continues.

- AD 8 – Vipsania Julia is exiled. Lucius Aemilius Paullus and his family are disgraced. Augustus breaks off the engagement of Claudius to Paullus' daughter Aemilia Lepida. An effort is made to betroth Claudius to Livia Medullina Camilla.

- AD 8 – After completing Metamorphoses, Ovid begins the Fasti (Festivals), 6 books that detail the first 6 months of the year and provide valuable insights into the Roman calendar.

- AD 8 – Roman poet Ovid is banished from Rome and exiled to the Black Sea near Tomis (modern-day Constanța).

- AD 9, c. September 9 – Battle of the Teutoburg Forest: Legio XVII, XVIII and XIX are lured by Arminius into an ambush and defeated by his tribe, the Cherusci, and their Germanic allies. The Roman aquilae are lost and the Roman general and governor Publius Quinctilius Varus dies by suicide. Legio II Augusta, XX Valeria Victrix, and XIII Gemina move to Germany to replace the lost legions.

- AD 9 – The Bellum Batonianum (Great Illyrian Revolt) in Dalmatia is suppressed.

- AD 9 – First record of the subdivision of the province of Illyricum into lower (Pannonia) and upper (Dalmatia) regions.

- AD 9 – In order to increase the number of marriages, and ultimately the population, the Lex Papia Poppaea is adopted in Italy. This law prohibits celibacy and childless relationships.

- AD 9 – Roman finances become strained following the Danubian insurrection and the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, resulting in the levying of two new taxes: five percent on inheritances, and one percent on sales.

- AD 9 – Cunobeline is first recorded to be king of the Catuvellauni at Camulodunum (modern-day Colchester) in Britain.

- AD 9 – Ovid completes the curse poem Ibis.

Demographics

[edit]Estimates for the world population in 1 AD range from 150 to 300 million. The below table summarizes estimates by various authors.

| PRB

(1973–2016)[30] |

UN

(2015)[31] |

Maddison

(2008)[32] |

HYDE

(2010)[33] |

Tanton

(1994)[34] |

Biraben

(1980)[35] |

McEvedy &

Jones (1978)[36] |

Thomlinson

(1975)[37] |

Durand

(1974)[38] |

Clark

(1967)[39] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300M[40] | 300M | 231M[41] | 188M[42] | 150M | 255M | 170M | 200M | 270–330M | 256M[43] |

Significant people

[edit]- Erato, Artaxiad dynasty Queen of Armenia, 8–5 BC, 2 BC – 2 AD, 6–11

- Ariobarzan of Atropatene, Client King of Armenia, r. 1 BC – 2 AD

- Artavazd V, Client King of Armenia, r. 2–11

- Tigranes V, Artaxiad dynasty King of Armenia, r. 2–6

- Ping Di, Emperor of Han dynasty China, r. 1 BC – 5 AD

- Ruzi Ying, Emperor of Han dynasty China, r. 6–9

- Wang Mang, Usurper Emperor of the short-lived Xin dynasty in China r. 9–23

- Antiochus III, King of Commagene, r. 12 BC – 17 AD

- Arminius, German war chief

- Arshak II, King of Caucasian Iberia, r. 20 BC-1 AD

- Pharasmanes I, King of Caucasian Iberia, r. 1-58

- Strato II and Strato III, co-kings of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, r. 25 BC – 10 AD

- Crimthann Nia Náir, Legendary High King of Ireland, r. 8 BC – AD 9

- Cairbre Cinnchait, Legendary High King of Ireland, r. 9–14

- Suinin, Legendary Emperor of Japan, r. 29 BC – 70 AD

- Natakamani, King of Kush, r. (1 BC – AD 20)

- Abgar V of Edessa, King of Osroene, 4 BC–AD 7, 13–50

- Ma'nu IV, King of Osroene, 7–13

- Phraates V, King of the Parthian Empire, r. 2 BC – 4 AD

- Musa of Parthia, mother and co-ruler with Phraates V, r. 2 BC – 4 AD

- Orodes III, King of the Parthian Empire, r. 4–6

- Vonones I, King of the Parthian Empire, r. 8–12

- Artabanus of Parthia, pretender to the Parthian throne and future King of Parthia

- Caesar Augustus, Roman Emperor (27 BC – AD 14)

- Gaius Caesar, Roman general

- Livy, Roman historian

- Ovid, Roman poet

- Quirinius, Roman nobleman and politician

- Hillel the Elder, Jewish scholar and Nasi of the Sanhedrin, in office c. 31 BC – 9 AD

- Shammai, Jewish scholar and Av Beit Din of the Sanhedrin, in office 20 BC – 20 AD

- Tiberius, Roman general, statesman, and future emperor

- Hyeokgeose, King of Silla, r. 57 BC – 4 AD

- Namhae, King of Silla, r. 4–24

Births

[edit]- AD 1 – Sextus Afranius Burrus, Roman praetorian prefect (d. AD 62)

- AD 1 – Izates II, King of Adiabene (d. AD 54)

- AD 1 – Seneca the Younger, Roman stoic philosopher was born in Cordoba (d. AD 65)[44]

- AD 2 – Deng Yu, Chinese general and statesman (d. AD 58)[45]

- AD 3 – Ban Biao, Chinese historian and official (d. AD 54)[46]

- AD 3 – Geng Yan, Chinese general of the Han dynasty (d. AD 58)

- AD 3 – Tiberius Claudius Balbilus, Roman politician and astrologer (d. AD 79)

- AD 4 – Columella, Roman Latin writer (d. AD 70)

- AD 4 – Daemusin, Korean king of Goguryeo (d. AD 44)

- AD 4 – Publius Quinctilius Varus the Younger, Roman nobleman (d. AD 27)

- AD 4 – Possible date – Jesus, Jewish preacher and religious leader (executed c. AD 30/33)[47]

- AD 5 – Habib the Carpenter, Syrian disciple, martyr

- AD 5 – Paul the Apostle, Jewish leader of the Christians

- AD 5 – Ruzi Ying, great-grandson of Xuan of Han (d. AD 25)

- AD 5 – Yin Lihua, empress of the Han dynasty (d. AD 64)

- AD 6 – Gaius Manlius Valens, Roman senator and consul (d. AD 96)

- AD 6 – John the Apostle, Jewish Christian mystic (d. AD 100)

- AD 6 – Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Roman politician (d. AD 39)

- AD 6 – Milonia Caesonia, Roman empress (d. AD 41)

- AD 6 – Nero Julius Caesar, son of Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder (d. AD 30)

- AD 7 – Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, Roman general (d. AD 67)

- AD 7 – Julia, daughter of Drusus Julius Caesar and Livilla (d. AD 43)

- AD 8 – Drusus Caesar, member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (d. AD 33)

- AD 8 – Titus Flavius Sabinus, Roman consul and brother of Vespasian (d. AD 69)

- AD 9, November 17 – Vespasian, Roman emperor (d. AD 79)[48]

Deaths

[edit]- AD 1 – Amanishakheto, queen of Kush (Nubia)

- AD 2, August 20 – Lucius Caesar, son of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder (b. 17 BC)[49]

- AD 2 – Gaius Marcius Censorinus, Roman consul (approximate date)

- AD 3 – Bao Xuan, Chinese politician of the Han dynasty

- AD 4 – February 21 – Gaius Caesar, son of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder (b. 20 BC)[50]

- AD 4 – June 26 – Ariobarzanes II, Roman client king of Armenia (b. 40 BC)

- AD 4 – Gaius Asinius Pollio, Roman orator, poet and historian (b. 65 BC)[51]

- AD 4 – Hyeokgeose, Korean king of Silla (b. 75 BC)

- AD 4 – Lucius Cornelius Lentulus, Roman consul

- AD 6, February 3 – Ping, Chinese emperor of the Han dynasty (b. 9 BC)

- AD 6 – Cleopatra Selene II, Egyptian ruler of Cyrenaica and Libya (b. 40 BC)

- AD 6 – Orodes III, king (shah) of the Parthian Empire

- AD 6 – Terentia, wife of Marcus Tullius Cicero (b. 98 BC)

- AD 7 – Athenodoros Cananites, Stoic philosopher (b. 74 BC)

- AD 7 – Aulus Licinius Nerva Silianus, Roman consul

- AD 7 – Glaphyra, daughter of Archelaus of Cappadocia (approximate date)

- AD 7 – Lucius Sempronius Atratinus, Roman politician

- AD 8 – Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus, Roman general (b. 64 BC)[52]

- AD 9, September 15 – Publius Quinctilius Varus, Roman general (b. 46 BC)

- AD 9 – Marcus Caelius, Roman centurion (b. c. 45 BC)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Murdoch, Adrian (2004). "Germania Romana". In Murdoch, Brian; Read, Malcolm (eds.). Early Germanic Literature and Culture. Boydell & Brewer. p. 57. ISBN 157113199X.

- ^ a b c Declercq, Georges (2000). Anno Domini: The origins of the Christian Era. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. pp. 143–147. ISBN 978-2503510507.

- ^ a b c Declercq, Georges (2002). "Dionysius Exiguus and the introduction of the Christian Era". Sacris Erudiri. 41. Brussels: Brepols: 165–246. doi:10.1484/J.SE.2.300491. ISSN 0771-7776.

Annotated version of a portion of Anno Domini

- ^ Going by Daryaee (2012) Daryaee, Touraj (2012). "Appendix: Ruling Dynasties of Iran". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–432. ISBN 978-0199875757.

- ^ Roller, Duane W (2003). The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Thomas A. Wilson (2003), in Xinzhong Yao (Ed.), RoutledgeCurzon Encyclopedia of Confucianism, "Baocheng Xuan Ni Gong", p. 26.

- ^ Book of Han, 12.351

- ^ a b Klingaman, William K. (1991). The first century : emperors, gods and everyman. Internet Archive. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-12887-9.

- ^ "Wang Mang | emperor of Xin dynasty". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- ^ a b c d e Klingaman, William K. (1990). The First Century: Emperors, Gods and Everyman. Harper-Collins. ISBN 978-0785822561.

- ^ "Kingship ii. Parthian Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 5 August 2025.

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, The Roman History, Book II. p 271.

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj. The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History Oxford University Press, 2012, p. 173

- ^ Dunn, James D. G. (2003). Jesus Remembered. Christianity in the Making. Vol. 1. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 324. ISBN 978-0802839312.

- ^ "Cassius Dio - Book 55". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2023-06-12.

- ^ "Augustus". HISTORY. Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- ^ Cassius Dio, The Roman Histories, Book 55, ch 26.

- ^ Cassius Dio, The Roman Histories, Book 55, ch 26-27.

- ^ Cassius Dio, The Roman Histories, Book 55, ch 25.

- ^ Parker, John Henry (1879). The Archaeology of Rome: Forum romanum et magnum. Vol. 5 (2nd ed.).

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, The Roman Histories, Book 55, ch 27.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, The Roman Histories, Book 55, ch 29.

- ^ a b Velleius Paterculus, Book 2, Ch 110.

- ^ Cassius Dio, The Roman Histories, Book 55, ch 30.

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, Book 2, Ch 111.

- ^ Cassius Dio, The Roman Histories, Book 55, ch 25-30.

- ^ Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, Tiberius, ch 9 & ch 16.

- ^ Cassius Dio, The Roman Histories, Book 55, ch 28.

- ^ Radman-Livaja, I., Dizda, M., Archaeological Traces of the Pannonian Revolt 6–9 AD: Evidence and Conjectures, Veröffentlichungen der Altertumskommiion für Westfalen Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe, Band XVIII, p. 49

- ^ Data from Population Reference Bureau Archived 2008-05-20 at the Wayback Machine. 2016 estimate: (a) "2016 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2017-08-28 at the Wayback Machine 2015 estimate: (b) Toshiko Kaneda, 2015, "2015 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2018-02-19 at the Wayback Machine. 2014 estimate: (c) Carl Haub, 2014, "2014 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2018-02-18 at the Wayback Machine. 2013 estimate: (d) Carl Haub, 2013, "2013 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2015-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. 2012 estimate: (e) Carl Haub, 2012, "2012 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2014-05-21 at the Wayback Machine. 2011 estimate: (f) Carl Haub, 2011, "2011 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2017-11-18 at the Wayback Machine. 2010 estimate: (g) Carl Haub, 2010, "2010 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2018-01-09 at the Wayback Machine. 2009 estimate: (h) Carl Haub, 2009, "2009 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2010-04-22 at the Wayback Machine. 2008 estimate: (i) Carl Haub, 2008, "2008 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2017-12-19 at the Wayback Machine. 2007 estimate: (j) Carl Haub, 2007, "2007 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2011-02-24 at the Wayback Machine. 2006 estimate: (k) Carl Haub, 2006, "2006 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2010-12-22 at the Wayback Machine. 2005 estimate: (l) Carl Haub, 2005, "2005 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2011-04-14 at the Wayback Machine. 2004 estimate: (m) Carl Haub, 2004, "2004 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2017-03-29 at the Wayback Machine. 2003 estimate: (n) Carl Haub, 2003, "2003 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2019-08-19 at the Wayback Machine. 2002 estimate: (o) Carl Haub, 2002, "2002 World Population Data Sheet" Archived 2017-12-09 at the Wayback Machine. 2001 estimate: (p) Carl Haub, 2001, "2001 World Population Data Sheet". 2000 estimate: (q) 2000, "9 Billion World Population by 2050" Archived 2018-02-01 at the Wayback Machine. 1997 estimate: (r) 1997, "Studying Populations". Estimates for 1995 and prior: (s) Carl Haub, 1995, "How Many People Have Ever Lived on Earth?" Population Today, Vol. 23 (no. 2), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Data from United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 1950–2100 estimates (only medium variants shown): (a) World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision. Archived 2011-05-11 at the Wayback Machine Estimates prior to 1950: (b) "The World at Six Billion", 1999. Estimates from 1950 to 2100: (c) "Population of the entire world, yearly, 1950 - 2100", 2013. Archived November 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine 2014: (d) http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/Highlights/WUP2014-Highlights.pdf "2014 World Urbanization Prospects", 2014.] 2015: (e) http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/Key_Findings_WPP_2015.pdf"2015 World Urbanization Prospects", 2015.] Archived March 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Angus Maddison, 2003, The World Economy: Historical Statistics, Vol. 2, OECD, Paris Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine ISBN 92-64-10412-7. "Statistical Appendix" (2008, ggdc.net) "The historical data were originally developed in three books: Monitoring the World Economy 1820-1992, OECD, Paris 1995; The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective, OECD Development Centre, Paris 2001; The World Economy: Historical Statistics, OECD Development Centre, Paris 2003. All these contain detailed source notes. Figures for 1820 onwards are annual, wherever possible. For earlier years, benchmark figures are shown for 1 AD, 1000 AD, 1500, 1600 and 1700." "OECD countries GDP revised and updated 1991-2003 from National Accounts for OECD Countries, vol. I, 2006. Norway 1820-1990 GDP from Ola Grytten (2004), "The Gross Domestic Product for Norway, 1830-2003" in Eitrheim, Klovland and Qvigstad (eds), Historical Monetary Statistics for Norway, 1819-2003, Norges Bank, Oslo. Latin American GDP 2000-2003 revised and updated from ECLAC, Statistical Yearbook 2004 and preliminary version of the 2005 Yearbook supplied by Andre Hofman. For Chile, GDP 1820-2003 from Rolf Lűders (1998), "The Comparative Economic Performance of Chile 1810-1995", Estudios de Economia, vol. 25, no. 2, with revised population estimates from Diaz, J., R. Lűders, and G. Wagner (2005) Chili 1810-2000: la Republica en Cifras, mimeo, Instituto de Economia, Universidad Católica de Chile. For Peru, GDP 1896-1990 and population 1896-1949 from Bruno Seminario and Arlette Beltran, Crecimiento Economico en el Peru 1896-1995, Universidad del Pacifico, 1998. " "For Asia there are amendments to the GDP estimates for South and North Korea, 1911-74, to correct an error in Maddison (2003). Estimates for the Philippines, 1902-1940 were amended in line with Richard Hooley (2005), 'American Economic Policy in the Philippines, 1902-1940', Journal of Asian Economics, 16. 1820 estimates were amended for Hong Kong, the Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan and Thailand." "Asian countries GDP revised and updated 1998-2003 from AsianOutlook, April 2005. Population estimates for all countries except China and Indonesia revised and updated 1950-2008 and 2030 from International Data Base, International Programs Center, Population Division, US Bureau of the Census, April 2005 version. China's population 1990-2003 from China Statistical Yearbook 2005, China Statistics Press, Beijing. Indonesian population 1950-2003 kindly supplied by Pierre van der Eng. The figures now include three countries previously omitted: Cook Islands, Nauru and Tuvalu."

- ^ Klein Goldewijk, K., A. Beusen, M. de Vos and G. van Drecht (2011). The HYDE 3.1 spatially explicit database of human induced land use change over the past 12,000 years, Global Ecology and Biogeography20(1): 73-86. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00587.x (pbl.nl). HYDE (History Database of the Global Environment), 2010. HYDE 3.1 gives estimates for 5000 BC, 1000 BC and "AD 0". HYDE estimates are higher than those by Colin McEvedy (1978) but lower than those by Massimo Livi Bacci (1989, 2012). (graphs (itbulk.org)).

- ^ Slightly updated data from original paper in French: (a) Jean-Noël Biraben, 1980, "An Essay Concerning Mankind's Evolution", Population, Selected Papers, Vol. 4, pp. 1–13. Original paper in French: (b) Jean-Noël Biraben, 1979, "Essai sur l'évolution du nombre des hommes", Population, Vol. 34 (no. 1), pp. 13–25.

- ^ Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones, 1978, Atlas of World Population History, Facts on File, New York, ISBN 0-7139-1031-3.

- ^ Ralph Thomlinson, 1975, Demographic Problems: Controversy over population control, 2nd Ed., Dickenson Publishing Company, Ecino, CA, ISBN 0-8221-0166-1.

- ^ John D. Durand, 1974, "Historical Estimates of World Population: An Evaluation", University of Pennsylvania, Population Center, Analytical and Technical Reports, Number 10.

- ^ Colin Clark, 1967, Population Growth and Land Use, St. Martin's Press, New York, ISBN 0-333-01126-0.

- ^ Haub (1995): "By 1 A.D., the world may have held about 300 million people. One estimate of the population of the Roman Empire, from Spain to Asia Minor, in 14 A.D. is 45 million. However, other historians set the figure twice as high, suggesting how imprecise population estimates of early historical periods can be."

- ^ "The present figures are a revision and update of those presented on this website in 2003. The most significant changes are in the entries for the year 1, where gaps in previous tables have been filled with the new estimates for the Roman Empire in Maddison (2007). The estimates are in fact for 14 AD"

- ^ Data from History Database of the Global Environment. K. Klein Goldewijk, A. Beusen and P. Janssen, "HYDE 3.1: Long-term dynamic modeling of global population and built-up area in a spatially explicit way", from table on pg. 2, Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (MNP), Bilthoven, The Netherlands.

- ^ The estimates are in fact for 14 AD"

- ^ Vogt, Katja (February 13, 2024). "Seneca". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ Fan, Ye. Book of the Later Han. Vol. 16.

- ^ "Ban Biao - Chinese official". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. (1993). The Historical Figure of Jesus (1st ed.). London: Allen Lane. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0713990591.

- ^ Kamm, Antony (August 13, 2008). The Romans: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-134-04799-4.

- ^ Suetonius (2000). Lives of the Caesars. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-953756-3.

- ^ Mommsen, Theodor (1996). Demandt, Alexander (ed.). A History of Rome Under the Emperors. Routledge (UK). p. 107. ISBN 978-0415101134.

- ^ Jerome (Chronicon 2020) says he died in AD 4 in the 70th year of his life, which would place the year of his birth at 65 BC.

- ^ Roberts, John. The Oxford dictionary of the classical world. Oxford University Press. p. 799. ISBN 9780192801463.