Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

African National Congress

View on Wikipedia

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election resulted in Nelson Mandela being elected as President of South Africa. Cyril Ramaphosa, the incumbent national president, has served as president of the ANC since 18 December 2017.[15]

Key Information

Founded on 8 January 1912 in Bloemfontein as the South African Native National Congress, the organisation was formed to advocate for the rights of black South Africans. When the National Party government came to power in 1948, the ANC's central purpose became to oppose the new government's policy of institutionalised apartheid. To this end, its methods and means of organisation shifted; its adoption of the techniques of mass politics, and the swelling of its membership, culminated in the Defiance Campaign of civil disobedience in 1952–53. The ANC was banned by the South African government between April 1960 – shortly after the Sharpeville massacre – and February 1990. During this period, despite periodic attempts to revive its domestic political underground, the ANC was forced into exile by increasing state repression, which saw many of its leaders imprisoned on Robben Island. Headquartered in Lusaka, Zambia, the exiled ANC dedicated much of its attention to a campaign of sabotage and guerrilla warfare against the apartheid state, carried out under its military wing, uMkhonto weSizwe, which was founded in 1961 in partnership with the South African Communist Party (SACP). The ANC was condemned as a terrorist organisation by the governments of South Africa, the United States, and the United Kingdom. However, it positioned itself as a key player in the negotiations to end apartheid, which began in earnest after the ban was repealed in 1990. For much of that time, the ANC leadership, along with many of its most active members, operated from abroad. After the Soweto Uprising of 1976, the ANC remained committed to achieving its objectives through armed struggle. These circumstances significantly shaped the ANC during its years in exile.[15]

In the post-apartheid era, the ANC continues to identify itself foremost as a liberation movement, although it is also a registered political party. Partly due to its Tripartite Alliance with the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), it had retained a comfortable electoral majority at the national level and in most provinces, and has provided each of South Africa's five presidents since 1994. South Africa is considered a dominant-party state. However, the ANC's electoral majority has declined consistently since 2004, and in the 2021 local elections, its share of the national vote dropped below 50% for the first time ever.[16] Over the last decade, the party has been embroiled in a number of controversies, particularly relating to widespread allegations of political corruption among its members.

Following the 2024 general election, the ANC lost its majority in parliament for the first time in South Africa's democratic history. However, it still remained the largest party, with just over 40% of the vote.[17] The party also lost its majority in Kwa-Zulu Natal, Gauteng and Northern Cape. Despite these setbacks, the ANC retained power at the national level through a grand coalition referred to as the Government of National Unity, including parties which together have 72% of the seats in Parliament.[18]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

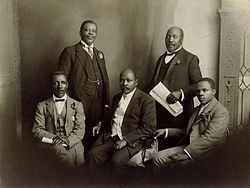

A successor of the Cape Colony's Imbumba Yamanyama organisation, the ANC was founded as the South African Native National Congress in Bloemfontein on 8 January 1912, and was renamed the African National Congress in 1923. Pixley ka Isaka Seme, Sol Plaatje, John Langalibalele Dube, and Walter Rubusana founded the organisation, who, like much of the ANC's early membership, were from the conservative, educated, and religious professional classes of black South African society.[19][20] Although they would not take part, Xhosa chiefs would show huge support for the organisation; as a result, King Jongilizwe donated 50 cows to it during its founding.[citation needed] Around 1920, in a partial shift away from its early focus on the "politics of petitioning",[21] the ANC developed a programme of passive resistance directed primarily at the expansion and entrenchment of pass laws.[20][22] When Josiah Gumede took over as ANC president in 1927, he advocated for a strategy of mass mobilisation and cooperation with the Communist Party, but was voted out of office in 1930 and replaced with the traditionalist Seme, whose leadership saw the ANC's influence wane.[19][21]

In the 1940s, Alfred Bitini Xuma revived some of Gumede's programmes, assisted by a surge in trade union activity and by the formation in 1944 of the left-wing ANC Youth League under a new generation of activists, among them Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, and Oliver Tambo.[19][20] After the National Party was elected into government in 1948 on a platform of apartheid, entailing the further institutionalisation of racial segregation, this new generation pushed for a Programme of Action which explicitly advocated African nationalism and led the ANC, for the first time, to the sustained use of mass mobilisation techniques like strikes, stay-aways, and boycotts.[20][23] This culminated in the 1952–53 Defiance Campaign, a campaign of mass civil disobedience organised by the ANC, the Indian Congress, and the coloured Franchise Action Council in protest of six apartheid laws.[24] The ANC's membership swelled.[21] In June 1955, it was one of the groups represented at the multi-racial Congress of the People in Kliptown, Soweto, which ratified the Freedom Charter, from then onwards a fundamental document in the anti-apartheid struggle.[21] The Charter was the basis of the enduring Congress Alliance, but was also used as a pretext to prosecute hundreds of activists, among them most of the ANC's leadership, in the Treason Trial.[25] Before the trial was concluded, the Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960. In the aftermath, the ANC was banned by the South African government. It was not unbanned until February 1990, almost three decades later.

Exile in Lusaka

[edit]After its banning in April 1960, the ANC was driven underground, a process hastened by a barrage of government banning orders, an escalation of state repression, and the imprisonment of senior ANC leaders pursuant to the Rivonia trial and Little Rivonia trial.[26] From around 1963, the ANC effectively abandoned much of even its underground presence inside South Africa and operated almost entirely from its external mission, with headquarters first in Morogoro, Tanzania, and later in Lusaka, Zambia.[27] For the entirety of its time in exile, the ANC was led by Tambo – first de facto, with president Albert Luthuli under house arrest in Zululand; then in an acting capacity, after Luthuli's death in 1967; and, finally, officially, after a leadership vote in 1985.[28] During the period there was an extremely close relationship between the ANC and the reconstituted South African Communist Party (SACP), which was also in exile.[28]

uMkhonto weSizwe

[edit]In 1961, partly in response to the Sharpeville massacre, leaders of the SACP and the ANC formed a military body, uMkhonto weSizwe (MK, Spear of the Nation), as a vehicle for armed struggle against the apartheid state. Initially, MK was not an official ANC body, nor had it been directly established by the ANC National Executive; it was considered an autonomous organisation until the ANC formally recognised it as its armed wing in October 1962.[29][26]

In the first half of the 1960s, MK was preoccupied with a campaign of sabotage attacks, especially bombings of unoccupied government installations.[29] As the ANC reduced its presence inside South Africa, however, MK cadres were increasingly confined to training camps in Tanzania and neighbouring countries – with such exceptions as the Wankie Campaign, a momentous military failure.[30] In 1969, Tambo was compelled to call the landmark Morogoro Conference to address the grievances of the rank-and-file, articulated by Chris Hani in a memorandum which depicted MK's leadership as corrupt and complacent.[31] Although MK's malaise persisted into the 1970s, conditions for armed struggle soon improved considerably, especially after the Soweto uprising of 1976 in South Africa saw thousands of students – inspired by Black Consciousness ideas – cross the borders to seek military training.[32] MK guerrilla activity inside South Africa increased steadily over this period, with one estimate recording an increase from 23 incidents in 1977 to 136 incidents in 1985.[33] In the latter half of the 1980s, a number of South African civilians were killed in these attacks, a reversal of the ANC's earlier reluctance to incur civilian casualties.[34][33] Fatal attacks included the 1983 Church Street bombing, the 1985 Amanzimtoti bombing, the 1986 Magoo's Bar bombing, and the 1987 Johannesburg Magistrate's Court bombing. Partly in retaliation, the South African Defence Force increasingly crossed the border to target ANC members and ANC bases, as in the 1981 raid on Maputo, 1983 raid on Maputo, and 1985 raid on Gaborone.[28]

During this period, MK activities led the governments of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan to condemn the ANC as a terrorist organisation.[35][36] In fact, neither the ANC nor Mandela were removed from the U.S. terror watch list until 2008.[37] The animosity of Western regimes was partly explained by the Cold War context, and by the considerable amount of support – both financial and technical – that the ANC received from the Soviet Union.[38][28]

Negotiations to end apartheid

[edit]From the mid-1980s, as international and internal opposition to apartheid mounted, elements of the ANC began to test the prospects for a negotiated settlement with the South African government, although the prudence of abandoning armed struggle was an extremely controversial topic within the organisation.[28] Following preliminary contact between the ANC and representatives of the state, business community, and civil society,[33][39] President F. W. de Klerk announced in February 1990 that the government would unban the ANC and other banned political organisations, and that Mandela would be released from prison.[40] Some ANC leaders returned to South Africa from exile for so-called "talks about talks", which led in 1990 and 1991 to a series of bilateral accords with the government establishing a mutual commitment to negotiations. Importantly, the Pretoria Minute of August 1990 included a commitment by the ANC to unilaterally suspend its armed struggle.[41] This made possible the multi-party Convention for a Democratic South Africa and later the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum, in which the ANC was regarded as the main representative of the interests of the anti-apartheid movement.

However, ongoing political violence, which the ANC attributed to a state-sponsored third force, led to recurrent tensions. Most dramatically, after the Boipatong massacre of June 1992, the ANC announced that it was withdrawing from negotiations indefinitely.[42] It faced further casualties in the Bisho massacre, the Shell House massacre, and in other clashes with state forces and supporters of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).[43] However, once negotiations resumed, they resulted in November 1993 in an interim Constitution, which governed South Africa's first democratic elections on 27 April 1994. In the elections, the ANC won an overwhelming 62.65% majority of the vote.[44] Mandela was elected president and formed a coalition Government of National Unity, which, under the provisions of the interim Constitution, also included the National Party and IFP.[45] The ANC has controlled the national government since then.

Breakaways

[edit]In the post-apartheid era, several significant breakaway groups have been formed by former ANC members. The first is the Congress of the People, founded by Mosiuoa Lekota in 2008 in the aftermath of the Polokwane elective conference, when the ANC declined to re-elect Thabo Mbeki as its president and instead compelled his resignation from the national presidency. The second breakaway is the Economic Freedom Fighters, founded in 2013 after youth leader Julius Malema was expelled from the ANC. Before these, the most important split in the ANC's history occurred in 1959, when Robert Sobukwe led a splinter faction of African nationalists to the new Pan Africanist Congress.

uMkhonto weSizwe rose to prominence in December 2023, when former president Jacob Zuma announced that, while planning to remain a lifelong member of the ANC, he would not be campaigning for the ANC in the 2024 South African general election, and would instead be voting for MK.[46] In July 2024, Jacob Zuma was expelled from the ANC, because of campaigning for a rival party (MK party) in the 29 May general election.[47]

Current structure and composition

[edit]

Leadership

[edit]Under the ANC constitution, every member of the ANC belongs to a local branch, and branch members select the organisation's policies and leaders.[48][49] They do so primarily by electing delegates to the National Conference, which is currently convened every five years. Between conferences, the organisation is led by its 86-member National Executive Committee, which is elected at each conference. The most senior members of the National Executive Committee are the so-called Top Six officials, the ANC president primary among them. A symmetrical process occurs at the subnational levels: each of the nine provincial executive committees and regional executive committees are elected at provincial and regional elective conferences respectively, also attended by branch delegates; and branch officials are elected at branch general meetings.[48]

Leagues

[edit]The ANC has three leagues: the Women's League, the Youth League and the Veterans' League. Under the ANC constitution, the leagues are autonomous bodies with the scope to devise their own constitutions and policies; for the purpose of national conferences, they are treated somewhat like provinces, with voting delegates and the power to nominate leadership candidates.[48]

Tripartite Alliance

[edit]The ANC is recognised as the leader of a three-way alliance, known as the Tripartite Alliance, with the SACP and Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU). The alliance was formalised in mid-1990, after the ANC was unbanned, but has deeper historical roots: the SACP had worked closely with the ANC in exile, and COSATU had aligned itself with the Freedom Charter and Congress Alliance in 1987.[50] The membership and leadership of the three organisations has traditionally overlapped significantly.[51] The alliance constitutes a de facto electoral coalition: the SACP and COSATU do not contest in government elections, but field candidates through the ANC, hold senior positions in the ANC, and influence party policy. However, the SACP, in particular, has frequently threatened to field its own candidates,[52] and in 2017 it did so for the first time, running against the ANC in by-elections in the Metsimaholo municipality, Free State.[53][54]

Electoral candidates

[edit]Under South Africa's closed-list proportional representation electoral system, parties have immense power in selecting candidates for legislative bodies. The ANC's internal candidate selection process is overseen by so-called "list committees" and tends to involve a degree of broad democratic participation, especially at the local level, where ANC branches vote to nominate candidates for the local government elections.[55][56] Between 2003 and 2008, the ANC also gained a significant number of members through the controversial floor crossing process, which occurred especially at the local level.[57][58]

The leaders of the executive in each sphere of government – the president, the provincial premiers, and the mayors – are indirectly elected after each election. In practice, the selection of ANC candidates for these positions is highly centralised, with the ANC caucus voting together to elect a pre-decided candidate. Although the ANC does not always announce whom its caucuses intend to elect,[59] the National Assembly has thus far always elected the ANC president as the national president.

Cadre deployment

[edit]The ANC has adhered to a formal policy of cadre deployment since 1985.[60] In the post-apartheid era, the policy includes but is not exhausted by selection of candidates for elections and government positions: it also entails that the central organisation "deploys" ANC members to various other strategic positions in the party, state, and economy.[61][62]

Ideology and policies

[edit]

The ANC prides itself on being a broad church,[63] and, like many dominant parties, resembles a catch-all party, accommodating a range of ideological tendencies.[64][65][66] As Mandela told The Washington Post in 1990:

The ANC has never been a political party. It was formed as a parliament of the African people. Right from the start, up to now, the ANC is a coalition, if you want, of people of various political affiliations. Some will support free enterprise, others socialism. Some are conservatives, others are liberals. We are united solely by our determination to oppose racial oppression. That is the only thing that unites us. There is no question of ideology as far as the odyssey of the ANC is concerned, because any question approaching ideology would split the organization from top to bottom. Because we have no connection whatsoever except at this one, of our determination to dismantle apartheid.[67]

The post-apartheid ANC continues to identify itself foremost as a liberation movement, pursuing "the complete liberation of the country from all forms of discrimination and national oppression".[48] It also continues to claim the Freedom Charter of 1955 as "the basic policy document of the ANC".[68][48] However, as NEC member Jeremy Cronin noted in 2007, the various broad principles of the Freedom Charter have been given different interpretations, and emphasised to differing extents, by different groups within the organisation.[66][69] Nonetheless, some basic commonalities are visible in the policy and ideological preferences of the organisation's mainstream.

Non-racialism

[edit]The ANC is committed to the ideal of non-racialism and to opposing "any form of racial, tribalistic or ethnic exclusivism or chauvinism".[48][65][70]

National Democratic Revolution

[edit]The 1969 Morogoro Conference committed the ANC to a "national democratic revolution [which] – destroying the existing social and economic relationship – will bring with it a correction of the historical injustices perpetrated against the indigenous majority and thus lay the basis for a new – and deeper internationalist – approach".[71] For the movement's intellectuals, the concept of the National Democratic Revolution (NDR) was a means of reconciling the anti-apartheid and anti-colonial project with a second goal, that of establishing domestic and international socialism – the ANC is a member of the Socialist International,[14] and its close partner the SACP traditionally conceives itself as a vanguard party.[65] Specifically, and as implied by the 1969 document, NDR doctrine entails that the transformation of the domestic political system (national struggle, in Joe Slovo's phrase) is a precondition for a socialist revolution (class struggle).[65][72] The concept remained important to ANC intellectuals and strategists after the end of apartheid.[73][74] Indeed, the pursuit of the NDR is one of the primary objectives of the ANC as set out in its constitution.[48] As with the Freedom Charter, the ambiguity of the NDR has allowed it to bear varying interpretations. For example, whereas SACP theorists tend to emphasise the anti-capitalist character of the NDR, some ANC policymakers have construed it as implying the empowerment of the black majority even within a market-capitalist scheme.[65]

Economic interventionism

[edit]We must develop the capacity of government for strategic intervention in social and economic development. We must increase the capacity of the public sector to deliver improved and extended public services to all the people of South Africa.

Since 1994, consecutive ANC governments have held a strong preference for a significant degree of state intervention in the economy. The ANC's first comprehensive articulation of its post-apartheid economic policy framework was set out in the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) document of 1994, which became its electoral manifesto and also, under the same name, the flagship policy of Nelson Mandela's government. The RDP aimed both to redress the socioeconomic inequalities created by colonialism and apartheid, and to promote economic growth and development; state intervention was judged a necessary step towards both goals.[75] Specifically, the state was to intervene in the economy through three primary channels: a land reform programme; a degree of economic planning, through industrial and trade policy; and state investments in infrastructure and the provision of basic services, including health and education.[75][76] Although the RDP was abandoned in 1996, these three channels of state economic intervention have remained mainstays of subsequent ANC policy frameworks.

Neoliberal turn

[edit]In 1996, Mandela's government replaced the RDP with the Growth Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) programme, which was maintained under President Thabo Mbeki, Mandela's successor. GEAR has been characterised as a neoliberal policy,[77][78] and it was disowned by both COSATU and the SACP.[79][80] While some analysts viewed Mbeki's economic policy as undertaking the uncomfortable macroeconomic adjustments necessary for long-term growth,[65] others – notably Patrick Bond – viewed it as a reflection of the ANC's failure to implement genuinely radical transformation after 1994.[81] Debate about ANC commitment to redistribution on a socialist scale has continued: in 2013, the country's largest trade union, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, withdrew its support for the ANC on the basis that "the working class cannot any longer see the ANC or the SACP as its class allies in any meaningful sense".[82] It is evident, however, that the ANC never embraced free-market capitalism, and continued to favour a mixed economy: even as the debate over GEAR raged, the ANC declared itself (in 2004) a social-democratic party,[83] and it was at that time presiding over phenomenal expansions of its black economic empowerment programme and the system of social grants.[84][85]

Developmental state

[edit]As its name suggests, the RDP emphasised state-led development – that is, a developmental state – which the ANC has typically been cautious, at least in its rhetoric, to distinguish from the neighbouring concept of a welfare state.[86][85][76] In the mid-2000s, during Mbeki's second term, the notion of a developmental state was revived in South African political discourse when the national economy worsened;[76] and the 2007 National Conference whole-heartedly endorsed developmentalism in its policy resolutions, calling for a state "at the centre of a mixed economy... which leads and guides that economy and which intervenes in the interest of the people as a whole".[86] The proposed developmental state was also central to the ANC's campaign in the 2009 elections,[76] and it remains a central pillar of the policy of the current government, which seeks to build a "capable and developmental" state.[87][88] In this regard, ANC politicians often cite China as an aspirational example.[63][89] A discussion document ahead of the ANC's 2015 National General Council proposed that:

China['s] economic development trajectory remains a leading example of the triumph of humanity over adversity. The exemplary role of the collective leadership of the Communist Party of China in this regard should be a guiding lodestar of our own struggle.[90]

Radical economic transformation

[edit]Towards the end of Jacob Zuma's presidency, an ANC faction aligned to Zuma pioneered a new policy platform referred to as radical economic transformation (RET). Zuma announced the new focus on RET during his February 2017 State of the Nation address,[91] and later that year, explaining that it had been adopted as ANC policy and therefore as government policy, defined it as entailing "fundamental change in the structures, systems, institutions and patterns of ownership and control of the economy, in favour of all South Africans, especially the poor".[92] Arguments for RET were closely associated with the rhetorical concept of white monopoly capital.[93][94] At the 54th National Conference in 2017, the ANC endorsed a number of policy principles advocated by RET supporters, including their proposal to pursue land expropriation without compensation as a matter of national policy.[95][96][97]

Foreign policy and relations

[edit]The ANC has long had close ties with China and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), with the CCP having supported ANC's struggle of apartheid since 1961.[98] In 2008, the two parties signed a memorandum of understanding to train ANC members in China.[99]

President Cyril Ramaphosa and the ANC have not condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and have faced criticism from opposition parties,[100][101][102] public commentators,[103][104] academics,[105][106] civil society organisations,[107][108][109] and former ANC members[110] due to this. The ANC youth wing has meanwhile condemned sanctions against Russia and denounced NATO's eastward expansion as "fascistic".[111][112] Officials representing the ANC Youth League acted as international observers for Russia's staged referendum to annex Ukrainian territory claimed during the war.[113] In February 2024 ANC Secretary-General Fikile Mbalula attend a "forum on combating Western neocolonialism"[114] hosted by Russia, thereby drawing further criticism for the party's perceived support for Russia's invasion.[114][115]

The ANC had received large donations from the Putin linked Russian oligarch Viktor Vekselberg, whilst the party's investment arm, Chancellor House, has a joint investment with Vekselberg in a South African manganese mine.[116][117]

Symbols and media

[edit]

Flag and logo

[edit]The logo of the ANC incorporates a spear and shield – symbolising the historical and ongoing struggle, armed and otherwise, against colonialism and racial oppression – and a wheel, which is borrowed from the 1955 Congress of the People campaign and therefore symbolises a united and non-racial movement for freedom and equality.[118] The logo uses the same colours as the ANC flag, which comprises three horizontal stripes of equal width in black, green and gold. The black symbolises the native people of South Africa; the green represents the land of South Africa; and the gold represents the country's mineral and other natural wealth.[118] The black, green and gold tricolour also appeared on the flag of the KwaZulu bantustan and appears on the flag of the ANC's rival, the IFP; and all three colours appear in the post-apartheid South African national flag.

Publications

[edit]Since 1996, the ANC Department of Political Education has published the quarterly Umrabulo political discussion journal; and ANC Today, a weekly online newsletter, was launched in 2001 to offset the alleged bias of the press.[119] In addition, since 1972, it has been traditional for the ANC president to publish annually a so-called January 8 Statement: a reflective letter sent to members on 8 January, the anniversary of the organisation's founding.[120] In earlier years, the ANC published a range of periodicals, the most important of which was the monthly journal Sechaba (1967–1990), printed in the German Democratic Republic and banned by the apartheid government.[121][122] The ANC's Radio Freedom also gained a wide audience during apartheid.[123]

Amandla

[edit]"Amandla ngawethu", or the Sotho variant "Matla ke arona", is a common rallying call at ANC meetings, roughly meaning "power to the people".[118] It is also common for meetings to sing so-called struggle songs, which were sung during anti-apartheid meetings and in MK camps. In the case of at least two of these songs – Dubula ibhunu and Umshini wami – this has caused controversy in recent years.[124]

Criticism and controversy

[edit]The ANC has received criticism from both internal and external sources. Internally Mandela publicly criticized the party, following the conclusion of his presidency, for ignoring instances of corruption and mismanagement, whilst allowing for the growth of a culture of racial and ideological intolerance.[125][126]

Corruption controversies

[edit]The most prominent corruption case involving the ANC relates to a series of bribes paid to companies involved in the ongoing R55 billion Arms Deal saga, which resulted in a long term jail sentence to then Deputy President Jacob Zuma's legal adviser Schabir Shaik. Zuma, the former South African President, was charged with fraud, bribery and corruption in the Arms Deal, but the charges were subsequently withdrawn by the National Prosecuting Authority of South Africa due to their delay in prosecution.[127] The ANC has also been criticised for its subsequent abolition of the Scorpions, the multidisciplinary agency that investigated and prosecuted organised crime and corruption, and was heavily involved in the investigation into Zuma and Shaik. Tony Yengeni, in his position as chief whip of the ANC and head of the Parliaments defence committee has recently been named as being involved in bribing the German company ThyssenKrupp over the purchase of four corvettes for the SANDF.[citation needed]

Other corruption issues in the 2000s included the sexual misconduct and criminal charges of Beaufort West municipal manager Truman Prince,[128] and the Oilgate scandal, in which millions of Rand in funds from a state-owned company were funnelled into ANC coffers.[129]

The ANC has also been accused of using government and civil society to fight its political battles against opposition parties such as the Democratic Alliance. The result has been a number of complaints and allegations that none of the political parties truly represent the interests of the poor.[130][131] This has resulted in the "No Land! No House! No Vote!" Campaign which became very prominent during elections.[132][133] In 2018, The New York Times reported on the killings of ANC corruption whistleblowers.[134]

During an address on 28 October 2021, former president Thabo Mbeki commented on the history of corruption within the ANC. He reflected that Mandela had already warned in 1997 that the ANC was attracting individuals who viewed the party as "a route to power and self-enrichment." He added that the ANC leadership "did not know how to deal with this problem."[135] During a lecture on 10 December, Mbeki reiterated concerns about "careerists" within the party, and stressed the need to "purge itself of such members".[136]

In May 2024, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in association with amaBhungane showed in documents that R200 million in the ANC's election fund was siphoned off to the church of controversial archbishop Bheki Lukhele in Eswatini; the Chief Financial Officer of the ANC, Bongani Mahlalela along with the Ambassador of Eswatini to Belgium, Sibusisiwe Mngomezulu, were implicated in the scheme.[137][138][139]

Condemnation over Secrecy Bill

[edit]In late 2011, the ANC was heavily criticised over the passage of the Protection of State Information Bill, which opponents claimed would improperly restrict the freedom of the press.[140] Opposition to the bill included otherwise ANC-aligned groups such as COSATU. Notably, Nelson Mandela and other Nobel laureates Nadine Gordimer, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and F. W. de Klerk have expressed disappointment with the bill for not meeting standards of constitutionality and aspirations for freedom of information and expression.[141]

Role in the Marikana killings

[edit]The ANC have been criticised for its role in failing to prevent 16 August 2012 massacre of Lonmin miners at Marikana in the Northwest. Some[who?] allege that Police Commissioner Riah Phiyega and Police Minister Nathi Mthethwa gave the go ahead for the police action against the miners on that day.[142]

Commissioner Phiyega of the ANC came under further criticism as being insensitive and uncaring when she was caught smiling and laughing during the Farlam Commission's video playback of the massacre.[143]

In 2014, Archbishop Desmond Tutu announced that he could no longer bring himself to vote for the ANC, as it was no longer the party that he and Nelson Mandela fought for. He stated that the party had lost its way, and was in danger of becoming a corrupt entity in power.[144]

Financial mismanagement

[edit]Since at least 2017, the ANC has encountered significant problems related to financial mismanagement. According to a report filed by the former treasurer-general Zweli Mkhize in December 2017, the ANC was technically insolvent as its liabilities exceeded its assets.[145] These problems continued into the second half of 2021. By September 2021, the ANC had reportedly amassed a debt exceeding R200-million, including over R100-million owed to the South African Revenue Service.[146]

Beginning in May 2021, the ANC failed to pay monthly staff salaries on time. Having gone without pay for three consecutive months, workers planned a strike in late August 2021.[147] In response, the ANC initiated a crowdfunding campaign to raise money for staff salaries.[148] By November 2021, its Cape Town staff was approaching their fourth month without salaries, while medical aid and provident fund contributions had been suspended in various provinces.[149] The party has countered that the Political Party Funding Act, which prohibits anonymous contributions, has dissuaded some donors who previously injected money for salaries.[150]African National Congress failed to pay Ezulweni investments R150 million rand historic debt.[151]

State capture

[edit]In January 2018, then-President Jacob Zuma established the Zondo Commission to investigate allegations of state capture, corruption, and fraud in the public sector.[152] Over the following four years, the Commission heard testimony from over 250 witnesses and collected more than 150,000 pages of evidence.[153] After several extensions, the first part of the final three-part report was published on 4 January 2022.[154][155]

The report found that the ANC, including Zuma and his political allies, had benefited from the extensive corruption of state enterprises, including the South African Revenue Service.[156] It also found that the ANC "simply did not care that state entities were in decline during state capture or they slept on the job – or they simply didn't know what to do."[157]

Election results

[edit]

National Assembly elections

[edit]| Election | Party leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Position | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Nelson Mandela | 12,237,655 | 62.65% | 252 / 400

|

ANC–NP–IFP coalition | ||

| 1999 | Thabo Mbeki | 10,601,330 | 66.35% | 266 / 400

|

ANC–IFP coalition | ||

| 2004 | 10,880,915 | 69.69% | 279 / 400

|

Majority | |||

| 2009 | Jacob Zuma | 11,650,748 | 65.90% | 264 / 400

|

Majority | ||

| 2014 | 11,436,921 | 62.15% | 249 / 400

|

Majority | |||

| 2019 | Cyril Ramaphosa | 10,026,475 | 57.50% | 230 / 400

|

Majority | ||

| 2024 | 6,459,683 | 40.18%[a] | 159 / 400

|

National Unity coalition |

- ^ From 2024, seats in the National Assembly are determined by a combination of the national ballot, and the nine regional ballots. Only the national ballot figures are shown here.

National Council of Provinces elections

[edit]| Election | Party leader | Seats | +/– | Position | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Nelson Mandela | 60 / 90

|

ANC–NP–IFP coalition | ||

| 1999 | Thabo Mbeki | 63 / 90

|

ANC–IFP coalition | ||

| 2004 | 65 / 90

|

Majority | |||

| 2009 | Jacob Zuma | 62 / 90

|

Majority | ||

| 2014 | 60 / 90

|

Majority | |||

| 2019 | Cyril Ramaphosa | 54 / 90

|

Majority | ||

| 2024 | 43 / 90

|

National Unity coalition |

Provincial legislatures

[edit]| Election[158] | Eastern Cape | Free State | Gauteng | KwaZulu-Natal | Limpopo | Mpumalanga | North-West | Northern Cape | Western Cape | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | |

| 1994 | 84.35 | 48/56 | 76.65 | 24/30 | 57.60 | 50/86 | 32.23 | 26/81 | 91.63 | 38/40 | 80.69 | 25/30 | 83.33 | 26/30 | 49.74 | 15/30 | 33.01 | 14/42 |

| 1999 | 73.80 | 47/63 | 80.79 | 25/30 | 67.87 | 50/73 | 39.38 | 32/80 | 88.29 | 44/49 | 84.83 | 26/30 | 78.97 | 27/33 | 64.32 | 20/30 | 42.07 | 18/42 |

| 2004 | 79.27 | 51/63 | 81.78 | 25/30 | 68.40 | 51/73 | 46.98 | 38/80 | 89.18 | 45/49 | 86.30 | 27/30 | 80.71 | 27/33 | 68.83 | 21/30 | 45.25 | 19/42 |

| 2009 | 68.82 | 44/63 | 71.10 | 22/30 | 64.04 | 47/73 | 62.95 | 51/80 | 84.88 | 43/49 | 85.55 | 27/30 | 72.89 | 25/33 | 60.75 | 19/30 | 31.55 | 14/42 |

| 2014 | 70.09 | 45/63 | 69.85 | 22/30 | 53.59 | 40/73 | 64.52 | 52/80 | 78.60 | 39/49 | 78.23 | 24/30 | 67.39 | 23/33 | 64.40 | 20/30 | 32.89 | 14/42 |

| 2019 | 68.74 | 44/63 | 61.14 | 19/30 | 50.19 | 37/73 | 54.22 | 44/80 | 75.49 | 38/49 | 70.58 | 22/30 | 61.87 | 21/33 | 57.54 | 18/30 | 28.63 | 12/42 |

| 2024[159] | 62.16 | 45/73 | 51.87 | 16/30 | 34.76 | 28/80 | 16.99 | 14/80 | 73.30 | 48/64 | 51.31 | 27/51 | 57.73 | 21/38 | 49.34 | 15/30 | 19.55 | 8/42 |

Municipal elections

[edit]| Election | Votes | % | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995–96 | 5,033,855 | 58% | |

| 2000 | None released | 59.4% | |

| 2006 | 17,466,948 | 66.3% | |

| 2011 | 16,548,826 | 61.9% | |

| 2016[160] | 21,450,332 | 55.7% | |

| 2021 | 14,531,908 | 47.5% |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harper, Paddy (18 December 2022). "Existential crisis-ANC membership drops by more than one third in five years". Mail and Guardian. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "South Africa • Africa Elects".

- ^ "How Democratic is the African National Congress? | Request PDF". Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ [2][3]

- ^ Lissoni, Arianna; Soske, JON; Erlank, Natasha; Nieftagodien, Noor; Badsha, Omar, eds. (2012). One Hundred Years of the ANC. doi:10.18772/22012115737. ISBN 978-1-77614-287-3. JSTOR 10.18772/22012115737.

- ^ Fatton, Robert (2 February 1984). "The African National Congress of South Africa: The Limitations of a Revolutionary Strategy". Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des Études Africaines. 18 (3): 593–608. doi:10.1080/00083968.1984.10804082. JSTOR 484771.

- ^ [5][6]

- ^ De Beus, Jos; Koelble, Tom (2001). "The Third Way diffusion of social democracy: Western Europe and South Africa compared". South African Journal of Political Studies. 28 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1080/02589340120091646.

- ^ "South Africa" (PDF). European Social Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Winning, Alexander; Roelf, Wendell; Toyana, Mfuneko (6 May 2019). "South Africa's Ramaphosa faces obstacles to reform". Reuters. Retrieved 30 August 2025.

- ^ Gumede, William. "How the EFF has shifted SA politics to the left". University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ a b Burke, Jason (18 December 2017). "Cyril Ramaphosa chosen to lead South Africa's ruling ANC party". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ Cele, S'thembile (4 November 2021). "ANC Support Falls Below 50% for First Time in South African Vote". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "In a historic election, South Africa's ANC loses majority for the first time". NPR. 1 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Chothia, Farouk; Kupemba, Danai Kesta; Plett-Usher, Barbra (14 June 2024). "ANC and DA agree on South Africa unity government". BBC News. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Lodge, Tom (1983). "Black protest before 1950". Black Politics in South Africa Since 1945. Ravan Press. pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-0-86975-152-7. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d Butler, Anthony (2012). The Idea of the ANC. Jacana Media. ISBN 978-1-4314-0578-7. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d Suttner, Raymond (2012). "The African National Congress centenary: a long and difficult journey". International Affairs. 88 (4): 719–738. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01098.x. ISSN 0020-5850. JSTOR 23255615. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Clark, Nancy L.; Worger, William H. (2016). South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid (3rd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-12444-8. OCLC 883649263.

- ^ "38th National Conference: Programme Of Action: Statement of Policy Adopted". African National Congress. 17 December 1949. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Lodge, Tom (1983). "The creation of a mass movement: strikes and defiance, 1950-1952". Black Politics in South Africa Since 1945. Ravan Press. pp. 33–66. ISBN 978-0-86975-152-7. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Lodge, Tom (1983). "African political organisations, 1953-1960". Black Politics in South Africa Since 1945. Ravan Press. pp. 67–90. ISBN 978-0-86975-152-7.

- ^ a b Ellis, Stephen (1991). "The ANC in Exile". African Affairs. 90 (360): 439–447. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098442. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 722941. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ African National Congress (1997). "Appendix: ANC structures and personnel". Further submissions and responses by the African National Congress to questions raised by the Commission for Truth and Reconciliation. Pretoria: Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Ellis, Stephen (2013). External Mission: The ANC in Exile, 1960–1990. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933061-4. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b Stevens, Simon (1 November 2019). "The Turn to Sabotage by The Congress Movement in South Africa". Past & Present (245): 221–255. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtz030. hdl:1814/75043. ISSN 0031-2746.

- ^ Houston, Gregory; Ralinala, Rendani Moses (2004). "The Wankie and Sipolilo Campaigns". The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Vol. 1. Zebra Press. pp. 435–492. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Macmillan, Hugh (1 September 2009). "After Morogoro: the continuing crisis in the African National Congress (of South Africa) in Zambia, 1969–1971". Social Dynamics. 35 (2): 295–311. doi:10.1080/02533950903076386. ISSN 0253-3952. S2CID 143455223. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ Ellis, Stephen (1994). "Mbokodo: Security in ANC Camps, 1961–1990". African Affairs. 93 (371): 279–298. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098712. hdl:1887/9075. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 723845. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Lodge, Tom (1987). "State of Exile: The African National Congress of South Africa, 1976–86". Third World Quarterly. 9 (1): 1, 282–310. doi:10.1080/01436598708419960. ISSN 0143-6597. JSTOR 3991845. PMID 12268882. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Williams, Rocky (2000). "The other armies: A brief historical overview of Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK), 1961–1994". Military History Journal. 11 (5). Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Waxman, Olivia B. (18 July 2018). "The U.S. Government Had Nelson Mandela on Terrorist Watch Lists Until 2008. Here's Why". Time. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ McSmith, Andy (10 December 2013). "Margaret Thatcher branded ANC 'terrorist' while urging Nelson Mandela's release". The Independent. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Windrem, Robert (7 December 2013). "US government considered Nelson Mandela a terrorist until 2008". NBC News. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Shubin, Vladimir (1996). "The Soviet Union/Russian Federation's Relations with South Africa, with Special Reference to the Period since 1980". African Affairs. 95 (378): 5–30. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007713. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 723723. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Brits, J. P. (2008). "Thabo Mbeki and the Afrikaners, 1986–2004". Historia. 53 (2): 33–69. ISSN 0018-229X. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Ottaway, David (3 February 1990). "S. Africa Lifts Ban on ANC, Other Groups". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ Simpson, Thula (2009). "Toyi-Toyi-ing to Freedom: The Endgame in the ANCs Armed Struggle, 1989–1990". Journal of Southern African Studies. 35 (2): 507–521. doi:10.1080/03057070902920015. hdl:2263/14707. ISSN 0305-7070. JSTOR 40283245. S2CID 145785746.

- ^ Keller, Bill (24 June 1992). "Mandela, Stunned by Massacre, Pulls Out of Talks on Black Rule". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Van Baalen, Sebastian (2014). "The Microdynamics of Conflict Escalation : The Case of ANC-IFP Fighting in South Africa in 1990". Pax et Bellum Journal. 1 (1): 14–20. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ "Elections '94". Independent Electoral Commission. 28 June 2008. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ Drogin, Bob (7 May 1994). "Ex-Guerrillas, Exiles Named to Mandela Cabinet". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ ""The battle for the soul of uMkhonto weSizwe"".

- ^ "South Africa's ex-President Jacob Zuma expelled from ANC". www.bbc.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "African National Congress Constitution, as amended and adopted by the 54th National Conference" (PDF). African National Congress. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Darracq, V. (18 August 2008). "The African National Congress (ANC) organization at the grassroots". African Affairs. 107 (429): 589–609. doi:10.1093/afraf/adn059. ISSN 0001-9909.

- ^ Twala, Chitja; Kompi, Buti (1 June 2012). "The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the Tripartite Alliance: a marriage of (in)convenience?". Journal for Contemporary History. 37 (1): 171–190. hdl:10520/EJC133152. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Buhlungu, Sakhela; Ellis, Stephen (1 January 2013). "The trade union movement and the Tripartite Alliance: a tangled history". Cosatu's Contested Legacy: 259–282. doi:10.1163/9789004214606_013. ISBN 9789004214606. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Bandile, Dineo (15 July 2017). "SACP resolves to contest state power independently of the ANC". The Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Mailovich, Claudi (29 November 2017). "SACP breaks alliance ranks in local election". Business Day. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "SACP governs its first municipality". News24. 21 December 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Mac Giollabhui, Shane (18 August 2018). "Battleground: candidate selection and violence in Africa's dominant political parties". Democratization. 25 (6): 978–995. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1451841. ISSN 1351-0347. S2CID 218523954.

- ^ Giollabhuí, Shane Mac (2013). "How things fall apart: Candidate selection and the cohesion of dominant parties in South Africa and Namibia". Party Politics. 19 (4): 577–600. doi:10.1177/1354068811407599. ISSN 1354-0688. S2CID 145444345.

- ^ Booysen, Susan (2006). "The Will of the Parties Versus the Will of the People?: Defections, Elections and Alliances in South Africa". Party Politics. 12 (6): 727–746. doi:10.1177/1354068806068598. ISSN 1354-0688. S2CID 145011059.

- ^ McLaughlin, Eric (2012). "Electoral regimes and party-switching: Floor-crossing in South Africa's local legislatures". Party Politics. 18 (4): 563–579. doi:10.1177/1354068810389610. ISSN 1354-0688. S2CID 143948206.

- ^ Myburgh, James (6 March 2009). "The ANC's secret premier candidates". PoliticsWeb. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Cadre Policy and Deployment Strategy" (PDF). Umrabulo. 6. 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Twala, Chitja (2014). "The African National Congress (ANC) and the Cadre Deployment Policy in the Postapartheid South Africa: A Product of Democratic Centralisation or a Recipe for a Constitutional Crisis?". Journal of Social Sciences. 41 (2): 159–165. doi:10.1080/09718923.2014.11893352. ISSN 0971-8923. S2CID 73526447.

- ^ Swanepoel, Cornelis F. (14 December 2021). "The slippery slope to State capture: cadre deployment as an enabler of corruption and a contributor to blurred party-State lines". Law, Democracy and Development. 25: 1–23. doi:10.17159/2077-4907/2021/ldd.v25.15. S2CID 245698431.

- ^ a b Duarte, Jessie (30 October 2018). "ANC policy remains the broad church for all South Africans". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Southall, Roger (2005). "The 'Dominant Party Debate' in South Africa". Africa Spectrum. 40 (1): 61–82. ISSN 0002-0397. JSTOR 40175055.

- ^ a b c d e f Butler, Anthony (2005). "How Democratic Is the African National Congress?". Journal of Southern African Studies. 31 (4): 719–736. doi:10.1080/03057070500370472. ISSN 0305-7070. JSTOR 25065043. S2CID 144481513.

- ^ a b Darracq, Vincent (2008). "Being a 'Movement of the People' and a Governing Party: Study of the African National Congress Mass Character". Journal of Southern African Studies. 34 (2): 429–449. doi:10.1080/03057070802038090. ISSN 0305-7070. JSTOR 40283147. S2CID 143326762.

- ^ "'We'll never fold our arms in the face of the evil of... apartheid'". The Washington Post. 27 June 1990. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Who We Are". African National Congress. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Suttner, Raymond (2015). "The Freedom Charter @ 60: Rethinking its democratic qualities". Historia. 60 (2): 1–23. doi:10.17159/2309-8392/2015/V60N2A1. S2CID 148443043.

- ^ Ndebele, Nhlanhla (1 November 2002). "The African National Congress and the policy of non-racialism: A study of the membership issue". Politikon. 29 (2): 133–146. doi:10.1080/0258934022000027763. ISSN 0258-9346. S2CID 154036222.

- ^ "Report on the Strategy and Tactics of the African National Congress" (PDF). African National Congress. 26 April 1969. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Slovo, Joe (1988). "The South African Working Class and the National Democratic Revolution" (PDF). Umsebenzi Discussion Pamphlet. South African Communist Party. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Netshitenzhe, Joel. "Understanding the tasks of the moment". Umrabulo. 25. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008.

- ^ Marwala, T. "The anatomy of capital and the national democratic revolution". Umrabulo. 29. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011.

- ^ a b "The Reconstruction and Development Programme: A Policy Framework" (PDF). African National Congress. 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Seekings, Jeremy (2015). "The 'Developmental' and 'Welfare' State in South Africa: Lessons for the Southern African Region" (PDF). Centre for Social Science Research Working Paper (358). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Adelzadeh, Asghar (1996). "From the RDP to GEAR: The Gradual embracing of Neo-liberalism in economic policy". Occasional Paper Series No. 3. Johannesburg: National Institute for Economic Policy. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Narsiah, Sagie (2002). "Neoliberalism and privatisation in South Africa". GeoJournal. 57 (1–2): 3–13. Bibcode:2002GeoJo..57....3N. doi:10.1023/A:1026022903276. S2CID 144352281. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Ngonyama, Percy (16 October 2006). "The ideological differences within the Tripartite Alliance: What now for the left?". Independent Media Centre. Archived from the original on 24 June 2008.

- ^ Southall, Roger J.; Wood, Geoffrey (1999). "COSATU, the ANC and the Election: Whither the Alliance?". Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa (38): 68–81.

- ^ Bond, Patrick (2000). The Elite Transition: From Apartheid to Neoliberalism in South Africa. London: Pluto Press. p. 53.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (20 December 2013). "South Africa's Biggest Trade Union Pulls Its Support for A.N.C." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022.

- ^ The Mail & Guardian A-Z of South African Politics by Barbara Ludman, Paul Stober, and Ferial Haffagee

- ^ Seekings, Jeremy (2021), "(Re)formulating the Social Question in Post-apartheid South Africa: Zola Skweyiya, Dignity, Development and the Welfare State", in Leisering, Lutz (ed.), One Hundred Years of Social Protection: The Changing Social Question in Brazil, India, China, and South Africa, Global Dynamics of Social Policy, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 263–300, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-54959-6_8, ISBN 978-3-030-54959-6, S2CID 230608172.

- ^ a b Bundy, Colin (6 September 2016). "The ANC and Social Security: The Good, the Bad and the Unacknowledged" (PDF). Poverty & Inequality Initiative. University of Cape Town. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b "52nd National Conference: Resolutions". African National Congress. 20 December 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Ramaphosa, Cyril (14 February 2022). "To grow our economy we need both a developmental state AND vibrant private sector". News24. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Khambule, Isaac (2021). "Capturing South Africa's developmental state: State-society relations and responses to state capture". Public Administration and Development. 41 (4): 169–179. doi:10.1002/pad.1912. ISSN 0271-2075. S2CID 236273471.

- ^ "My Chinese dream: ANC brass put ideas to work". The Mail & Guardian. 23 August 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "International Relations: A Better Africa In A Better And Just World" (PDF). Umrabulo. 2015. p. 161. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ^ Merten, Marianne (29 June 2017). "ANC policy, radical economic transformation and ideological proxy battles for control". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Paton, Carol (7 December 2017). "Foreign investors in energy sector will have to partner with locals, Zuma says". Business Day. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Rudin, Jeff (25 April 2017). "Zuma's plan for radical economic transformation is just BEE on steroids". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Desai, Ashwin (2 October 2018). "The Zuma moment: between tender-based capitalists and radical economic transformation". Journal of Contemporary African Studies. 36 (4): 499–513. doi:10.1080/02589001.2018.1522424. ISSN 0258-9001. S2CID 158520517.

- ^ "Zuma 'reminds' ANC what they 'resolved' about the Reserve Bank at Nasrec". The Citizen. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Merten, Marianne (31 May 2021). "Expropriation without compensation: ANC & EFF toenadering on state land custodianship — it's all about the politics". Daily Maverick. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Madia, Tshidi (30 June 2019). "ANC resolutions on Sarb, land and other matters will be my legacy – Ace Magashule on party policies". News24. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ "How the political seeds of China's growing Africa ties were planted long ago". South China Morning Post. 25 December 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Sun, Yun (5 July 2016). "Political party training: China's ideological push in Africa?". Brookings. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine: Someone needs to speak for SA". Democratic Alliance. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Tonder, Anthony van (23 March 2022). "SA Government's Position on Russia's Invasion of Ukraine Does Not Reflect the Views of ALL South Africans". ActionSA. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Makhafola, Getrude (15 March 2022). "'Yes, I studied in Russia' – MPs heckle during debate on Russia war in Ukraine". The Citizen. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Feldman, Howard. "Howard Feldman | Ukraine crisis: The ANC is standing on the wrong side of history". News24. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Polakow-Suransky, Sasha; McKaiser, Eusebius (18 March 2022). "South Africa's Self-Defeating Silence on Ukraine". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Nathan, Laurie (13 April 2022). "Russia's war in Ukraine: how South Africa blew its chance as a credible mediator". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Hamill, James (16 March 2022). "South Africa Has Clearly Chosen a Side on the War in Ukraine". World Politics Review. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Mills, Ray Hartley and Greg (6 March 2022). "WAR IN EUROPE OP-ED: Cries of pain and anguish — why the ANC is on the wrong side of history over Ukraine". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Fritz, Nicole. "ANC mirrors Poland's Law & Justice party in flirting with tyranny". BusinessLIVE. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Jurgens, Richard (4 July 2022). "Russia in Ukraine: South Africa's unprincipled stance". Good Governance Africa. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Jurgens, Richard (5 July 2022). "Foreign Relations Op-Ed: ANC government's position on Ukraine invasion unprincipled, inconsistent with SA values". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "German Embassy slaps down Russian claim its troops are fighting Nazism". The Independent. 7 March 2022. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Fabricius, Peter (6 March 2022). "INTERVIEW WITH US DEPUTY SECRETARY OF STATE: United States slaps down Ramaphosa's criticism of Biden's pre-war Russia diplomacy". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Fabricius, Peter (25 September 2022). "WAR IN EUROPE: ANC Youth League lends credibility to sham Moscow referendums in Ukraine". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ a b Masuabi, Queenin (13 February 2024). "Fikile Mbalula off to Moscow for forum on combating Western neocolonialism". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Capa, Siyamtanda. "Senior ANC delegation jets off to Moscow to join fight against 'new manifestation of colonialism'". News24. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ Gerber, Jan. "Lady R's cargo manifest is 'classified' claims ANC as opposition wants answers". News24. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "South African ties to Russia shadow Ukraine peace mission". France 24. 15 June 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "The Logo, Colours and Flag of the African National Congress". African National Congress. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Fourie, Pieter J. (2008). Media Studies Volume 2: Policy, Management and Media Representation (2nd ed.). Cape Town: Juta and Company. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7021-7675-3.

- ^ "ANC January 8th Statements". South African History Online. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Editorial: A Friend to Sechaba". Sechaba. 24 (12). 1990.

- ^ "Quoting the A.N.C." The New York Times. 29 December 1987. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Uhlig, Mark A. (12 October 1986). "Inside the African National Congress". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Langa, Retha (2 January 2018). "A 'Counter-Monument' to the Liberation Struggle: The Deployment of Struggle Songs in Post-Apartheid South Africa". South African Historical Journal. 70 (1): 215–233. doi:10.1080/02582473.2018.1439523. ISSN 0258-2473. S2CID 149388558.

- ^ "Mandela accuses ANC of racism and corruption". The Telegraph. 3 March 2001. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ "Mandela says ANC racist and corrupt". Irish Independent. 3 March 2001. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ "Opposition hails challenge to ANC rule". 9 October 2008.

- ^ Bester, Ronel (5 May 2005). "Action against Prince 'a farce'". Die Burger. Archived from the original on 7 May 2005.

- ^ "Special Report: Oilgate". Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ^ "DA councillor's role in Delft is 'criminal'". Cape Argus. 20 February 2008.

- ^ "DA's Delft councillor denies claims". Cape Argus. 28 February 2008.

- ^ "The 'No Land, No House, No Vote' campaign still on for 2009". Abahlali baseMjondolo. 5 May 2005.

- ^ "IndyMedia Presents: No Land! No House! No Vote!". Anti-Eviction Campaign. 12 December 2005. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009.

- ^ Norimitsu Onishi; Selam Gebrekidan (30 September 2018). "Hit Men and Power: South Africa's Leaders Are Killing One Another". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

"If you understand the Cosa Nostra, you don't only kill the person, but you also send a strong message," said Thabiso Zulu, another A.N.C. whistle-blower who, fearing for his life, is now in hiding. "We broke the rule of omertà," he added, saying that the party of Nelson Mandela had become like the Mafia.

- ^ Maphanga, Canny; Gerber, Jan (29 October 2021). "ANC has failed to keep people seeking 'self-enrichment' out of party". News24. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Maphanga, Canny (11 December 2021). "Many see their ANC membership as a ticket to power and resources – Thabo Mbeki". News24. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ Tshwane, Tebogo (30 April 2024). "The ANC, the megachurch and the mystery of the R200-million money flows". amaBhungane. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ Tshwane, Tebogo (8 May 2024). "The ANC, the megachurch, and the mystery money flows – Part Two: 'God's Laundry'". amaBhungane. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Millions in suspicious transactions tie South Africa's ruling party to a controversial Swazi archbishop, documents show – ICIJ". 26 May 2024. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ du Plessis, Charl (22 November 2011). "Secrecy bill opposition reaching fever pitch". Times Live.

- ^ AFP (22 November 2011). "Mandela's office comments on S Africa's secrecy bill". Dawn.

- ^ "Who gave permission to kill?: Bizos". Business Report. IOL. 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Marikana families horrified at Phiyegas behaviour". M&G. 24 October 2012.

- ^ Smith, David (25 April 2014). "Desmond Tutu: why I won't vote ANC". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Paton, Carol (20 December 2017). "ANC is technically insolvent, financial report shows". BusinessLIVE. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Mahlaka, Ray (12 September 2021). "The ANC, a tax evader? Massive debt, unpaid salaries, dry donation taps". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Madisa, Kgothatso (25 August 2021). "ANC offices shut down as unpaid staff go on 'wildcat strike'". Times LIVE. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Mthethwa, Cebelihle (28 August 2021). "ANC resorts to crowdfunding to raise money to pay staff". News24. Archived from the original on 13 September 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Ludidi, Velani (15 November 2021). "ANC staff picket over unpaid salaries". IOL. Weekend Argus. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Tebele, Karabo (28 July 2022). "ANC staff members to continue picket at Nasrec over unpaid salaries". CapeTalk 567AM. Archived from the original on 4 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ Mavuso, Sihle (11 August 2025). "ANC 'breaches' agreement to pay Ezulweni Investment's R150m historic debt". Sunday World. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Judicial Commission of Inquiry Into Allegations of State Capture (Call for evidence/information)". PMG. 22 June 2018. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Amashabalala, Mawande (21 December 2020). "'He was the president': Zondo says there's no place to hide for Zuma". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Mahlati, Zintle (31 December 2021). "Zondo to hand deliver State Capture Inquiry report to Ramaphosa on Tuesday". News24. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Judicial Commission of Inquiry into State Capture Report: Part 1" (PDF). 4 January 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Ferreira, Emsie (6 January 2022). "Zondo: ANC was either incompetent or asleep on capture". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Hunter, Qaanitah (6 January 2022). "ANC 'did not care or they slept on the job or they had no clue what to do' – Zondo Commission report". News24. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ "Results Dashboard". elections.org.za. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "NPE Results Dashboard 2024". results.elections.org.za. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Results Summary – All Ballots p" (PDF). elections.org.za. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Sechaba archive at JSTOR

- Mayibuye archive at JSTOR

- Attacks attributed to the ANC on the START terrorism database

- List of articles & videos about the ANC Archived 15 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Response by the ANC General Secretary to COSATU's assessment, 2004

- Finding aid for the African National Congress Oral History Transcripts Collection at the University of Connecticut Archives and Special Collections

African National Congress

View on GrokipediaHistory

Founding and Pre-Apartheid Activism (1912–1948)

The South African Native National Congress (SANNC) was established on 8 January 1912 in Bloemfontein by African chiefs, educators, and professionals responding to the political exclusion embedded in the 1910 Union of South Africa constitution, which denied voting rights to most Africans and entrenched white dominance.[4] Key founders included John Langalibalele Dube, elected as the first president; Pixley ka Isaka Seme, a Columbia-educated lawyer who organized the inaugural conference and served as treasurer; and Sol Plaatje, appointed secretary.[4][1] The organization sought to consolidate elite African voices from tribal, mission, and urban backgrounds to advocate for civil rights, focusing initially on uniting fragmented groups rather than mobilizing the broader populace.[5] Early SANNC strategies emphasized constitutional petitions to South African authorities and deputations to Britain, aiming to leverage imperial ties for redress against laws like urban pass requirements and rural land restrictions.[6] A 1914 delegation to London protested the impending Natives Land Act, which limited African land ownership to 7% of the territory, but received no substantive concessions from the British government.[6] Renamed the African National Congress (ANC) in 1923 to broaden its appeal beyond "native" connotations, the group maintained a moderate, petition-based approach through the 1920s and 1930s, submitting memoranda on issues like the Colour Bar Bill and achieving minor adjustments, such as exemptions for certain educated Africans from pass laws.[1] Membership remained small, numbering around 3,000 by the mid-1920s, reflecting its elite character and limited grassroots penetration.[4] The ANC's advocacy yielded partial reforms but failed to avert deepening segregation. The Representation of Natives Act of 1936 removed approximately 20,000 qualified African voters from the Cape Province's common roll— a franchise dating to 1853—and substituted indirect representation via three white MPs and a Natives Representative Council with advisory powers only.[7] Despite ANC-led protests and alliances with Indian and Coloured groups, the Act passed with Hertzog's National Party support, entrenching separate development and diminishing African parliamentary influence.[8] In the 1940s, amid World War II urbanization and labor shortages, ANC leaders like J.B. Marks—a mineworkers' union organizer—pushed for expanded alliances with the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) and non-European trade unions, such as the Council of Non-European Trade Unions, which Marks chaired from 1941.[9] These ties, involving CPSA members infiltrating ANC branches, introduced class-oriented tactics and prepared the ground for mass-oriented strategies, though the organization still prioritized legalism over confrontation by 1948.[10][11] This shift reflected growing frustration with petition failures but retained the ANC's non-violent framework during the pre-apartheid era.[6]Mass Resistance and Defiance Campaigns (1949–1960)

In December 1949, the ANC adopted the Programme of Action at its 38th National Conference, marking a strategic shift from petitions to mass mobilization through non-violent methods such as strikes, boycotts, and civil disobedience aimed at challenging discriminatory laws.[12][13] This policy, influenced by the ANC Youth League's advocacy for assertive African nationalism, sought national liberation by withdrawing cooperation from state institutions enforcing racial segregation.[14] The Programme guided the 1952 Defiance Campaign, launched on 26 June in coordination with the South African Indian Congress, where over 8,000 volunteers deliberately violated apartheid regulations like pass laws and segregation rules, courting arrest to overwhelm the judicial system.[15][16] The campaign, peaking with more than 2,000 arrests in October, spurred ANC membership growth from around 20,000 to 100,000, particularly in the Eastern Cape, demonstrating the efficacy of mass action in expanding organizational reach despite government suppression.[17][18] By 1955, the ANC, through the Congress Alliance—a coalition including the South African Indian Congress, Coloured Congress, and white Congress of Democrats with underground ties to banned communists—convened the Congress of the People in Kliptown on 25–26 June, where approximately 3,000 delegates adopted the Freedom Charter.[19][20] The Charter demanded universal suffrage, land redistribution, and economic equality, including nationalization of key industries, but its multiracial framework and collectivist provisions fueled internal ideological friction, as African nationalists in the Youth League viewed the alliance with Marxist-oriented elements as compromising pure African self-determination.[21] These tensions manifested in the 1959 formation of the Pan Africanist Congress by ANC dissidents rejecting the Congress Alliance's influence, yet mass defiance persisted into 1960 with protests against pass laws.[22] The Sharpeville shootings on 21 March, where police killed 69 unarmed demonstrators, triggered a national crisis, leading to the ANC's banning on 8 April alongside the PAC, curtailing legal non-violent operations and prompting a reevaluation of strategy.[22][23]Banning, Exile, and Internal Underground (1960–1970s)

Following the Sharpeville massacre on March 21, 1960, the South African government banned the ANC on April 8, 1960, under the Unlawful Organizations Act, declaring it unlawful and driving its activities underground or into exile.[24][1] Oliver Tambo, appointed acting president in the absence of imprisoned leaders, escaped to establish an external mission, initially based in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) and later relocating to Tanzania and Zambia.[25] By 1964, the ANC headquarters shifted to Lusaka, Zambia, where Tambo coordinated operations amid host country support from President Kenneth Kaunda.[26] In exile, the ANC prioritized diplomatic isolation of the apartheid regime, lobbying the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and United Nations for economic and arms sanctions, though comprehensive measures faced resistance from Western powers in the 1960s.[27] Efforts included establishing missions in Europe and Africa to garner international solidarity and funding, while navigating rivalries with the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) for limited liberation movement resources.[28] Internally, post-Rivonia Trial arrests in 1963–1964 decimated visible structures, but clandestine networks facilitated recruit exfiltration for training abroad, with over 300 cadres sent by mid-1963, primarily to Soviet-aligned countries and African states.[29] The 1970s saw gradual rebuilding of domestic underground cells amid severe repression, focusing on political mobilization rather than overt action, as state security dismantled early sabotage units.[30] Resource scarcity in exile exacerbated tensions, with dependence on Soviet military aid and OAU logistics straining the ANC's non-aligned stance and fostering internal debates over strategy, though Tambo's leadership maintained organizational cohesion.[31] The 1976 Soweto uprising, sparked by Afrikaans-language education policies, radicalized youth and swelled exile ranks, injecting new energy into Lusaka operations despite logistical strains from regional instabilities.[32] Factional undercurrents persisted, including SACP influence on policy, but did not fracture the core exile apparatus during this period.[33]Intensified Struggle and uMkhonto weSizwe (1970s–1980s)

Following the Soweto uprising on June 16, 1976, which resulted in hundreds of deaths primarily among black youth protesting Afrikaans-language instruction in schools, the African National Congress (ANC) experienced a significant recruitment surge into its armed wing, uMkhonto weSizwe (MK). Thousands of students and activists fled into exile, forming groups like the "June 16th Detachment" to join MK training camps in Angola, Mozambique, and Zambia, revitalizing the organization's military capacity after a period of dormancy in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[34] By the late 1970s, MK cadres numbered in the thousands, with operations shifting from sporadic sabotage to more frequent attacks on economic infrastructure, though apartheid security forces' infiltration—via agents and informants—led to numerous arrests and operational disruptions.[35] MK's intensified campaign in the 1980s focused on sabotage to disrupt the apartheid economy and state apparatus, with annual operations rising from approximately 20 in 1980 to 61 by 1984, targeting power stations, oil refineries, and military sites. Notable actions included the June 1, 1980, bombing of the Sasol oil refinery in Secunda, which damaged facilities but caused no immediate fatalities, and the May 20, 1983, Church Street car bomb in Pretoria near South African Air Force headquarters, which killed 19 people (including civilians of both racial groups) and injured over 200.[36][29][37] These attacks aimed to impose economic costs and signal vulnerability, but empirical assessments reveal limited strategic military success; MK achieved no territorial gains or conventional victories against the South African Defence Force, with most efforts confined to hit-and-run sabotage hampered by high infiltration rates and internal mutinies in exile camps.[35][38] The civilian toll from MK operations drew criticism for indiscriminate elements, as Truth and Reconciliation Commission findings later indicated that ANC attacks disproportionately affected non-combatants, including black workers and bystanders, despite directives to minimize such losses. For instance, landmine campaigns in rural areas from 1985–1987 resulted in at least 23 deaths, mostly civilians, while urban bombings like Church Street blurred lines between military and populated targets, fueling debates over proportionality.[39] Although MK actions correlated with escalating township unrest—such as the widespread 1984–1986 uprisings that rendered some areas ungovernable—and contributed to international isolation through heightened violence visibility, causal analysis suggests internal mass mobilization and economic grievances played larger roles in sustaining pressure on the regime than MK's tactical outputs, which suffered from logistical failures and a low success rate in evading security countermeasures.[40]Negotiations, Unbanning, and Transition to Democracy (1980s–1994)