Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Educational inequality

View on WikipediaThe examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2021) |

| Educational research |

|---|

| Disciplines |

| Curricular domains |

| Methods |

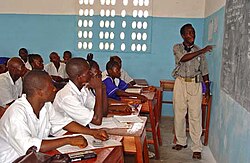

Educational Inequality is the unequal distribution of academic resources, including but not limited to school funding, qualified and experienced teachers, books, physical facilities and technologies, to socially excluded communities. These communities tend to be historically disadvantaged and oppressed. Individuals belonging to these marginalized groups are often denied access to schools with adequate resources and those that can be accessed are so distant from these communities. Inequality leads to major differences in the educational success or efficiency of these individuals and ultimately suppresses social and economic mobility. Inequality in education is broken down into different types: regional inequality, inequality by sex, inequality by social stratification, inequality by parental income, inequality by parent occupation, and many more.

Measuring educational efficacy varies by country and even provinces/states within the country. Generally, grades, GPA test scores, other scores, dropout rates, college entrance statistics, and college completion rates are used to measure educational success and what can be achieved by the individual. These are measures of an individual's academic performance ability. When determining what should be measured in terms of an individual's educational success, many scholars and academics suggest that GPA, test scores, and other measures of performance ability are not the only useful tools in determining efficacy.[1] In addition to academic performance, attainment of learning objectives, acquisition of desired skills and competencies, satisfaction, persistence, and post-college performance should all be measured and accounted for when determining the educational success of individuals. Scholars argue that academic achievement is only the direct result of attaining learning objectives and acquiring desired skills and competencies. To accurately measure educational efficacy, it is imperative to separate academic achievement because it captures only a student's performance ability and not necessarily their learning or ability to effectively use what they have learned.[2]

Much of educational inequality is attributed to economic disparities that often fall along racial lines, and much modern conversation about educational equity conflates the two, showing how they are inseparable from residential location and, more recently, language.[3] In many countries, there exists a hierarchy or a main group of people who benefit more than the minority people groups or lower systems in that area, such as with India's caste system for example. In a study about education inequality in India, authors, Majumbar, Manadi, and Jos Mooij stated "social class impinges on the educational system, educational processes and educational outcomes" (Majumdar, Manabi and Jos Mooij).[4]

However, there is substantial scientific evidence demonstrating that students’ socioeconomic status does not determine their academic success; rather, it is the actions implemented in schools that do. Successful Educational Actions (SEAs) previously identified and analysed in the INCLUD-ED project (2006-2011),[5] has proven to be an effective practice for addressing the inequalities in education faced by vulnerable populations.[6]

For girls who are already disadvantaged, having school available only for the higher classes or the majority of people group in a diverse place like South Asia can influence the systems into catering for one kind of person, leaving everyone else out. This is the case for many groups in South Asia. In an article about education inequality being affected by people groups, the organization Action Education claims that "being born into an ethnic minority group or linguistic minority group can seriously affect a child's chance of being in school and what they learn while there" (Action Education).[7] We see more and more resources only being made for certain girls, predominantly who speak the language of the city. In contrast, more girls from rural communities in South Asia are left out and thus not involved with school. Educational inequality between white students and minority students continues to perpetuate social and economic inequality.[1] Another leading factor is housing instability, which has been shown to increase abuse, trauma, speech, and developmental delays, leading to decreased academic achievement. Along with housing instability, food insecurity is also linked with reduced academic achievement, specifically in math and reading. Having no classrooms and limited learning materials negatively impacts the learning process for children. In many parts of the world, old and worn textbooks are often shared by six or more students at a time.[8]

Throughout the world, there have been continuous attempts to reform education at all levels.[9] With different causes that are deeply rooted in history, society, and culture, this inequality is difficult to eradicate. Although difficult, education is vital to society's movement forward. It promotes "citizenship, identity, equality of opportunity and social inclusion, social cohesion, as well as economic growth and employment," and equality is widely promoted for these reasons.[10] Global educational inequality is clear in the ongoing learning crisis, where over 91% of children across the world are enrolled in primary schooling; however, a large proportion of them are not learning. A World Bank study found that "53 percent of children in low- and middle-income countries cannot read and understand a simple story by the end of primary school."[11] The recognition of global educational inequality has led to the adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 which promotes inclusive and equitable quality education for all.

Unequal educational outcomes are attributed to several variables, including family of origin, gender, and social class. Achievement, earnings, health status, and political participation also contribute to educational inequality within the United States and other countries.[12] The ripple effect of this inequality are quite disastrous, they make education in Africa more of a theoretical rather than a practical experience majorly due to the lack of certain technological equipment that should accompany their education.

Family background

[edit]In Harvard's "Civil Rights Project," Lee and Orfield identify family background as the most influential factor in student achievement.[3] A correlation exists between the academic success of parents with the academic success of their children. Only 11% of children from the bottom fifth earn a college degree, while well over half of the top fifth earn one.[13] Linked with resources, White students tend to have more educated parents than students from minority families.[14] This translates to a home-life that is more supportive of educational success. This often leads to them receiving more at-home help, having more books in their home, attending more libraries, and engaging in more intellectually intensive conversations.[14] Children, then, enter school at different levels. Poor students are behind in verbal memory, vocabulary, math, and reading achievement and have more behavior problems.[15] This leads to their placement in different level classes that track them.[16] These courses almost always demand less from their students, creating a group that is conditioned to lack educational drive.[9] These courses are generally non-college bound and are taught by less-qualified teachers.[1]

Also, family background influences cultural knowledge and perceptions. Middle class중산층중산층 중산층 knowledge of norms and customs allows students with this background to navigate the school system better. Parents부모님부모 부모님모님 from this class and above also have social networks that are more beneficial than those based in lower classes. These connections may help students gain access to the right schools, activities, etc.[14] Additionally, children from poorer families, who are often minorities, come from families that distrust institutions.[14] America's history of racism and discrimination has created a perceived and/or existent ceiling on opportunities for many poor and minority citizens. This ceiling muffles academic inspirations and muffles growth.[14] Jonathan Wai concluded that during the COVID-19 pandemic, Harvard often provided more lip service than concrete measures to fully support students from minority and low-income communities. He also noted that poor students often faced greater disadvantages than wealthy students during the pandemic, exacerbating the existing economic inequalities at Harvard.[17]

The recent[when?] and drastic increase of Latino immigrants has created another major factor in educational inequality. As more and more students come from families where English is not spoken at home, they often struggle to overcome a language barrier and simply learn subjects.[3] They more frequently lack assistance at home because it is common for the parents not to understand the work that is in English.[16]

Furthermore, research reveals the summer months as a crucial time for the educational development of children. Students from disadvantaged families experience greater losses in skills during summer vacation.[15] Students from lower socioeconomic classes come disproportionately from single-parent homes and dangerous neighborhoods.[9] 15% of White children are raised in single-parent homes and 10% of Asian children are. 27% of Latinos are raised in single-parent homes and 54% of African-American children are.[16] Fewer resources, less parental attention, and more stress all influence children's performance in school.

A broad range of factors contributes to the emergence of socioeconomic achievement gaps. The interaction of different aspects of socialization is outlined in the model of mediating mechanisms between social background and learning outcomes.[19][18] The model describes a multi-step mediation process. Socially privileged families have more economic, personal, and social resources available than socially disadvantaged families. Differences in family resources result in differences in the learning environments experienced by children. Children with various social backgrounds experience different home learning environments, attend different early childhood facilities, schools, school-related facilities, and recreational facilities, and have different peer groups. Due to these differences in learning environments, children with various social backgrounds carry out different learning activities and develop different learning prerequisites.

Gender

[edit]Throughout the world, educational achievement varies by gender. The exact relationship differs across cultural and national contexts.

Female disadvantage

[edit]Obstacles preventing females' ability to receive a quality education include traditional attitudes towards gender roles, poverty, geographical isolation, gender-based violence, early marriage and pregnancy.[20] Throughout the world, there is an estimated 7 million more girls than boys out of school. This "girls gap" is concentrated in several countries including Somalia, Afghanistan, Togo, the Central African Republic, and Democratic Republic of the Congo. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, girls are outnumbered two to one.[21] The gender constructs of Southeast Asia run deep into history and affect all spheres of the future lives of young women. Traditional gender roles placed upon girls results in the drop of women from school and the trend of less educated older women in Southeast Asia. In a journal about the women of the Devanga community in India, Pooja Haridarshan says that "70% [of] women in South Asia are married at a young age, which is coupled with early childbearing and a lack of decision-making abilities within the traditional family structures, further enhancing their "disadvantaged" position in society" (Haridarshan).[22] The women are expected to marry young, bear and raise children, leaving little to no room for them to receive an education, encouraging youngers girls to also follow in their footsteps. But the scary thing is that less educated women could become poor because of their lack of resources. This is an unjust situation where there is an evident divide between men's educational success and women's education success. This is where our one brainstorms a solution. In an article about the wellbeing of children in South Asia, authors Jativa Ximena and Michelle Mills states that "in societies and communities where girls' mobility is restricted, more opportunities need to be provided for girls to continue education and skills training" (Ximena and Mills).[23]

Socialized gender roles affect females' access to education. For example, in Nigeria, children are socialized into their specific gender roles as soon as their parents know their gender. Men are the preferred gender and are encouraged to engage in computer and scientific learning while women learn domestic skills. These gender roles are deep-rooted within the state, however, with the increase of westernized education within Nigeria, there has been a recent increase in women's ability to receive an equal education. There is still much to be changed, though. Nigeria still needs policies that encourage educational attainment for men and women based on merit, rather than gender.[24]

Females are shown to be at risk of being attacked in at least 15 countries.[25] Attacks can occur because individuals within those countries do not believe women should receive an education. Attacks include kidnappings, bombings, torture, rape, and murder. In Somalia, girls have been abducted. In Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Libya students were reported to have been raped and harassed.[25] In Pakistan and Afghanistan, schools and busses have been bombed and gassed.[25] Early marriage affects females' ability to receive an education.[26][citation needed]

"The gap separating men and women in the job market remains wide in many countries, whether in the North or the South. With marginal variables between most countries, women have a lower employment rate, are unemployed longer, are paid less, and have less secure jobs."[27] "Young women, particularly suffer double discrimination. First for being young, in the difficult phase of transition between training and working life, in an age group that has, on an average, twice the jobless rate or older workers and are at the mercy of employers who exploit them under the pretext of enabling them to acquire professional experience. Secondly, they are discriminated against for being women and are more likely to be offered low paying or low-status jobs."[27] "Discrimination is still very much in evidence and education and training policies especially targeting young women are needed to restore a balance."[27] "Although young women are increasingly choosing typically 'male' professions, they remain over-represented in traditionally female jobs, such as secretaries, nurses, and underrepresented in jobs with responsibility and the professions."[27]

In early grades, boys and girls perform equally in mathematics and science, but boys score higher on advanced mathematics assessments such as the SAT college entrance examination.[28] Girls are also less likely to participate in class discussions and more likely to be silent in the classroom.[28] Some believe that females have a way of thinking and learning differently from males. Belenky and colleagues (1986) conducted research that found an inconsistency between the kind of knowledge appealing to women and the kind of knowledge being taught in most educational institutions.[28] Another researcher, Gilligan (1982), found that the knowledge appealing to females was caring, interconnection, and sensitivity to the needs of others, while males found separation and individualism appealing.[28] Females are more field-dependent, or group-oriented than males, which could explain why they may experience problems in schools that primarily teach using an individualistic learning environment.[28] As Teresa Rees finds, the variance of women in mathematics and science fields can be explained by the lack of attention paid to the gender dimension in science.[29]

Regarding gender differences in academic performance, Buchmann, DiPrete, and McDaniel claim that gender-based accomplishments on standardized tests show the continuation of the "growing male advantage in mathematics scores and growing female advantage in reading scores as they move through school".[30] Ceci, Williams and Barnett's research about women's underrepresentation in science reinforces this claim by saying that women experience "stereotype threat [which] impedes working memory" and as a result receive lower grades in standardized or mathematics tests.[31] Nonetheless, Buchmann, DiPrete and McDaniel claim that the decline of traditional gender roles, alongside the positive changes in the labor market that now allow women to get "better-paid positions in occupational sectors" may be the cause for a general incline in women's educational attainment.

Male disadvantage

[edit]

In 51 countries, girls are enrolled at higher rates than boys. Particularly in Latin America, the difference is attributed to the prominence of gangs and violence attracting male youth. The gangs pull the males in, distracting them from school and causing them to drop out.[25]

In some countries, female high school and graduation rates are higher than for males.[28] In the United States, for example, 33% more bachelor's degrees were conferred on females than males in 2010–2011.[32] This gap is projected to increase to 37% by 2021–2022 and is over 50% for masters and associate degrees. Dropout rates for males have also increased over the years in all racial groups, especially in African Americans. They have exceeded the number of high school and college dropout rates than any other racial ethnicity for the past 30 years. Most of the research found that males were primarily the most "left behind" in education because of higher graduation dropout rates, lower test scores, and failing grades. They found that as males get older, primarily from ages 9 to 17, they are less likely to be labeled "proficient" in reading and mathematics than girls were.

In general, males arrive in kindergarten much less ready and prepared for schooling than females. This creates a gap that continually increases over time into middle and high school. Nationally, there are 113 boys in 9th grade for every 100 girls, and among African-American males, there are 123 boys for every 100 girls. States have discovered that 9th grade has become one of the biggest dropout years.[33] Whitmire and Bailey continued their research and looked at the potential for any gender gap change when males and females were faced with the decision of potentially going to college. Females were more likely to go to college and receive bachelor's degrees than males were. From 1971 to about 1981, women were the less fortunate and had lower reported numbers of bachelor's degrees. However, since 1981, males have been at a larger disadvantage, and the gap between males and females keeps increasing.[33]

Boys are more likely to be disciplined than girls, and are also more likely to be classified as learning disabled.[28] Males of color, especially African-American males, experience a high rate of disciplinary actions and suspensions. In 2012, one in five African-American males received an out of school suspension.[34]

In Asia, males are expected to be the main financial contributor of the family. So many of them go to work right after they become adults physically, which means at the age of around 15 to 17. This is the age they should obtain a high school education.

Males get worse grades than females do regardless of year or country examined in most subjects.[35] In the U.S. women are more likely to have earned a bachelor's degree than men by the age of 29.[36] Female students graduate high school at a higher rate than male students. In the U.S. in 2003, 72 percent of female students graduated, compared with 65 percent of male students. The gender gap in graduation rates is particularly large for minority students.[37] Men are under-represented among both graduate students and those who successfully complete masters and doctoral degrees in the U.S.[38] Proposed causes include boys having worse self-regulation skills than girls and being more sensitive to school-quality and home environment than girls.[39][40] Boys perceiving education as feminine and lacking educated male role-models may also contribute to males being less likely to complete college.[41] It has been suggested that male students in the U.S. perform worse on reading tests and read less than their female counterparts in part because males are more physically active, more aggressive, less compliant, and because school reading curricula do not match their interests.[42] It has also been suggested that teacher bias in grading may account for up to 21% of the male deficit in grades.[43] One study found that male disadvantage in education is independent of inequality in social and economic participation.[44]

Race

[edit]In the United States

[edit]During the early 18th century, African-American students and Mexican-American students were barred from attending schools with white students in most states. This was due to the court case Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), in which it was decided that educational facilities were allowed to segregate white students from students of color as long as the educational facilities were considered equal. Educational facilities did not follow the federal mandate: a study covering the period 1890 to 1950 of the Southern states' per-pupil expenditures on instruction found that, on average, white students received 17 to 70 percent more educational expenditures than their Black counterparts.[45] The first federal legal challenge of these unequal segregated educational systems occurred in California – Mendez v. Westminster in 1947, followed by Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. The decision in Brown v. Board of Education led to the desegregation of schools by federal law, but decades of inferior education, segregation of household salaries between whites and people of color, and racial wealth gaps have left people of color at a disadvantage. According to the EdBuild report from 2019, non-white school districts receive 23 billion dollars less than white school districts, even though they serve the same number of students. School districts rely heavily on local taxes, so districts in white communities, which tend to be wealthier, receive more money per student than nonwhite districts: $13,908 per student, compared to $11,682 per student, respectively.[46]

Differences of academic skills in children of different races start at an early age. According to National Assessment of Educational Progress, there is a remaining gap[quantify] showing Black and Latino children being able to demonstrate cognitive proficiency compared to their Asian and White counterparts. In the data, 89 percent of Asian and White children presented the ability to understand written and spoken words while only 79 and 78 percent of Black and Latino children were able to comprehend written and spoken words the trend would continue into ages 4–6.[47]

Studies exploring the U.S. education systems' racial achievement disparities typically investigate factors like where students live, where they go to school,[48] family socioeconomic status (SES), and broader influences like structural racism.[49] Genetic and cultural explanations for social outcome disparities between racial groups are not supported,[50][51][52][53] increasingly disputed by educators,[54] and may indirectly contribute to inequitable outcomes by impacting expectations for students of color or distracting from policy-addressable issues by "blaming the victim."[55][56] For example, "debunked" theories attributing achievement disparities to "fear of acting white" may undermine policy support for addressing systemic issues such as economic inequality, implicit racial bias, and school discipline disparities.[57]

Immigration status

[edit]The Immigrant paradox states that "immigrants, who are disadvantaged by inequality, may use their disadvantages as a source of motivation". A study based in New York suggested that children of immigrant descent outperformed their native student counterparts. The paradox explains that the gratefulness of immigrant children allows them to enjoy academic advantages that may not have been accessible at one time. This in turn, allows for more effort and better outcomes from these students. This was also evident in the National Education Longitudinal Study which showed that immigrant children often achieved higher scores on math and science tests. It has been reported that "evidence of the immigrant advantage was stronger from Asian immigrant families than for youth from Latin American", which may cause some inequality in itself. This may vary depending on differences between pre and post-migration conditions.[58]

In 2010, researchers from Brown University published their results on how immigrant children are thriving in school. Some of their conclusions were that first-generation immigrant children show lower levels of delinquency and bad behaviors than generations beyond. This implies that first-generation immigrant children often start behind American-born children in school, but they progress quickly and have elevated rates of learning growth.[59] In the U.S., having more immigrant peers appears to increase U.S.-born students' chances of high school completion. Low-skilled immigration, in particular, is strongly associated with more years of schooling and improved academic performance by third-plus generation students.[60]

Many people[weasel words] assume that enough life skills will be presented to immigrant children to succeed. This is not always true as there is more to life than just getting through high school. The International Student Services Association (ISSA) has a goal to help foreign born students to succeed. The way they do this by providing two different programs within school hours, which can be adapted to accommodate each school and individual. Theses programs are called The Career Readiness Program and The College Readiness Program. The author Haowen Ge mentions, "Since their beginning in 2019, both programs have been extremely successful with 90% of ISSA students continuing to certification programs, college and/or internships."[61]

Just because these students have begun their enrollment in the education system does not mean they will remain there. According to SOS Children's Villages, "68 million people worldwide have fled their homes because of conflict, unrest or disaster. Children account for more than half of this total. Child refugees face incredible risks and dangers – including disease, malnutrition, violence, labor exploitation and trafficking."[62] People flee their homes because of anti-immigrant policies, which take tolls on the national school system of the United States. A national study's results show that "Ninety percent of administrators in this study observed behavioral or emotional problems in their immigrant students. And 1 in 4 said it was extensive."[63] This proves that the immigration policies within the United States takes a toll on these immigrant children in our education system.[64]

Latino students and college preparedness

[edit]Latino migration

[edit]In the United States, Latinos are the largest growing population. As of 1 July 2016, Latinos make up 17.8 percent of the U.S. population, making them the largest minority.[65] People from Latin America migrate to the United States due to their inability to obtain stability, whether it is financial stability or refugee. Their homeland is either dealing with an economic crisis or is involved in a war. The United States capitalizes on the migration of Latin American migrants. With the disadvantage of their legal status, American businesses employ them and pay them an extremely low wage.[66] As of 2013, 87% of undocumented men and 57% undocumented women were a part of the U.S. economy.[67] Diaspora plays a role in Latinos migrating to the United States. Diaspora is the dispersion of any group from their original homeland.[68]

New York City holds a substantial quota of the Latino population. More than 2.4 million Latinos inhabit New York City,[69] its largest Latino population being Puerto Ricans followed by Dominicans.[69] A large number of Latinos contributes to the statistic of at least four million of the United States born children having one immigrant parent.[70] Children of immigrant origin are the fastest growing population in the United States. One in every four children come from immigrant families.[71] Many Latino communities are constructed around immigrant origins in which play a big part in society. The growth in children of immigrant parents does not go unaware, in a way society and the government accepts it. For example, many undocumented/immigrants can file taxes, children who attend college can provide parents information to obtain financial aid, parent(s) may be eligible for government help through the child, etc. Yet, the lack of knowledge regarding post-secondary education financial help increases the gap of Latino children to restrain from obtaining higher education.[citation needed]

Education

[edit]In New York City, Mayor De Balsio has implemented 3-K for All, which every child can attend pre-school at the age of three, free of charge.[72] Although children's education is free from K-12 grade, many children with immigrant parents do not take advantage of all the primary education benefits. Children who come from a household that contains at least one immigrant parent, are less likely to attend childhood or preschool programs.[70]

College preparation

[edit]The preparation of college access to children born in America from immigrant parents pertaining to Latino communities is a complex process. The beginning of the junior year through senior year in high school consists of preparation for college research and application process. For government help towards college tuition such as Financial Aid and Taps, parents or guardian's personal information is needed, this is where doubt and anticipation unravels. The majority of immigrant parents/guardians do not have most of the qualifications required for the application. The focus is to portray the way immigrants and their American born children work around the education system to attain a college education. Due to the influx of the Latino population, there amount of Latino high school students graduates has increased as well.[73] Latino students are mainly represented in two-year rather than four-year institutions.[73] This can occur for two reasons: the cost reduction of attending a two-year institution or its close proximity to home.[74] Young teens with a desire to obtain a higher education clash with some limitations due to parent's/guardian's personal information.[70]

Many children lack public assistance due to lack of English proficiency of parents which is difficult to fill out forms or applications or simply due to the parent's fear of giving personal information that could identify their status, the same concept applies to Federal Student Aid. Federal Student Aid comes from the federal government in which helps a student pay for educational expenses of college in three possible formats, grant, work-study, and loan. One step of the Federal Aid application requires one or both parent/guardian personal information as well as financial information. This may limit the continuance of the application due to the fear of providing personal information. The chances of young teens entering college reduce when personal information from parents are not given. Many young teens with immigrant parents are part of the minority group in which income is not sufficient to pay college tuition or repay loans with interest. The concept of college as highly expensive makes Latino students less likely to attend a four-year institution or even attend postsecondary education. Approximately 50% of Latinos received financial aid in 2003–2004, but they are still the minority who received the lowest average of the federal awards.[75] In addition, loans are not typically granted to them.[75]

Standardized tests

[edit]In addition to finance scarcity, standardized tests are required when applying to a four-year post educational institution. In the United States, the two examinations that are normally taken are the SATs and ACTs. Latino students do generally take the exam, but from 2011 to 2015, there has been a 50% increase in the number of Latino students taking the ACTs.[76] As for the SATs, in 2017, 24% of the test takers were identified with Latino/Hispanic. Out of that percentage, only 31 percent met the college-readiness benchmark for both portions of the test (ERW and Math).[77]

Native American students and higher education

[edit]This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (September 2023) |

Economic disparity and representation

[edit]Economic disparity is a significant issue faced by Native American students that influences their placement in high-poverty and rural elementary and high schools, resulting in disadvantageous conditions for them to access higher education.[78] This disadvantage is further exacerbated by the underrepresentation of Native American students in gifted and talented programs, with lower identification rates compared to their White counterparts.[79] The scarcity of usable data on Native American students in gifted programming also mirrors a broader underrepresentation of this demographic within educational research.[79] This issue has been extensively scrutinized through peer-reviewed research, with an emphasis on its prevalence within various scholarly articles. Smith et al.'s (2014) study concentrated on the representation of Native American students in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) disciplines. Their research unearthed a notable underrepresentation of these students within STEM fields, contributing to both personal and societal disadvantages.[80]

Cultural values, identity, and support programs

[edit]Further insights emerge[editorializing] from Smith et al.'s (2014) study, highlighting the strong ties that many Native American students maintain with their tribal cultures and communities, along with their high regard for education's instrumental significance. This finding suggests that Native American students exhibit a proclivity towards endorsing individualistic goals, a potential asset for supporting their academic and career aspirations.[80] Moreover, specialized support programs have been shown to effectively address challenges faced by Native American students. These programs foster cultural identity, create a sense of community, and mitigate the negative impacts of racism experienced by these students. By enhancing belonging and reducing the racial/ethnic achievement gap, these initiatives play a vital role in promoting the academic success of Native American students in STEM fields.[80]

Cultural identity and academic persistence

[edit]Jackson et al. (2003) conducted a separate study exploring factors that influence the academic persistence of Native American college students. Their research highlighted the pivotal role of confidence in academic success and persistence. Confidence and competence emerged as key motivating factors for Native American students striving for academic achievement.[81] The study also emphasized the importance of accommodating Native American culture within educational institutions and addressing instances of racism, as these factors significantly impact students' persistence in higher education.[81]

Qualitative interviews with successful Native American college students identified themes related to their persistence in college, including dealing with racism and developing independence and assertiveness.[81] Lack of academic persistence among Native American students has been attributed to colleges' failure to accommodate Native American culture.[81] Furthermore, the personal experience of racism has been found to negatively impact Native American students' persistence in higher education.[81]

Early education racial inequality

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2022) |

Racial inequality affects students from a young age. High quality early childhood education programs, known as ECE, are offered to children, to help them enter kindergarten with a good understanding of how to succeed throughout school. There has been a noticeable difference in the quality of education, with Black or Hispanic groups being provided with less effective preschool learning programs than White non-Hispanic groups in the preschool setting. This causes White children to achieve a higher level of education than Black or Hispanic children. White children are more likely to enter into higher level ECE programs than Black or Hispanic children, with the latter being in cheaper and less effective education programs. The American Psychological Association said that "Research shows that compared with white students, black students are more likely to be suspended or expelled, less likely to be placed in gifted programs and subject to lower expectations from their teachers."[82]

In 2001–2004, eleven states conducted a study on the education quality gap between races in ECE programs and found that Black children were more likely to attend lower quality programs than Whites. A study of Black children entering kindergarten in 2016 found that they were behind in math and English by up to nine months, compared to White children. Kids who are behind in kindergarten are projected to stay behind throughout most of their career.[83] The 2016 study found that there still is a gap between races in ECE programs.[83] "Strikingly, minority students are about half as likely to be assigned to the most effective teachers and twice as likely to be assigned to the least effective."[84] As of 2016, 24% of White children are enrolled in high quality early education, whereas only 15% of Black children fall into that category. Tests run in 2016 proved that if Black and Hispanic children were to attend high quality early education for one year, the education gap in English, between them and White children, would nearly disappear, and for the gap in math to drop to around five months going into kindergarten.[83]

Rural and inner-city education

[edit]There are large scales systemic inequalities within rural and inner-city education systems. The study of these differences, especially within rural areas, is relatively new and distinct from the study of educational inequality which focuses on individuals within an educational system.

Rural and inner-city students in the United States under-perform academically compared to their suburban peers. Factors that influence this under-performance include funding, classroom environment, and the lessons taught.[85][86] Inner-city and rural students are more likely to live in low-income households and attend schools with fewer resources compared to suburban students.[87][88][89] They have also shown to have a less favorable view of education which stems from the values held in their communities and families regarding school, work, and success.[87][86]

When compared to suburban students, rural and inner-city students face similar achievement issues.[85] Teacher-student interactions, the lessons taught, and knowledge about the surrounding community have shown to be important factors in helping offset the deficits faced in inner-city and urban schools.[85][86] However, drop-out rates are still high within both communities, as a more substantial number of minority students, who often live in these areas, drop-out of high school.[85] A study on inner-city, high school students showed that academic competency during freshman year has a positive impact on graduation rates, meaning that a students' early high school performance can be an indicator of how successful they will be in high school and if they will graduate.[90] With the correct knowledge and understanding of the issues faced by these students, the deficits they face can be overcome.

Standardized tests

[edit]Achievement in the United States is often measured using standardized tests. Studies have shown that low performance on standardized tests can have a negative effect on the funding the school receives from the government, and low-income students have been shown to underperform on standardized tests at higher rates than their peers.[91][92] A study looking at how low test performance affected schools, found that schools that perform below average and are in low income areas can face repercussions that affect school funding and resources.[93] The study also found that the material taught to students is affected by test performance, as schools that have low test scores will often change their curriculum to teach to the test.[93]

School resources

[edit]In the same way, some regions of the world have so-called "brain drain", or the loss of wealthy, skilled, and educated individuals and their families to other countries through immigration, rural and inner-city regions of the United States experience brain drain to sub-urban regions.[94][89] It has been shown that people become more likely to leave rural areas as their education level increases and less likely as they increase in age.[94] Urban inner-city areas have been decentralizing since the 1950s, losing their human capital. This flight of human capital leaves only the poor and disadvantaged behind to contribute to school funding resulting in school systems that have very limited resources and financial difficulty.[89]

The American public school system is one in which the amount of wealth in a school district shapes the quality of the school because schools are primarily funded by local property taxes.[95] As the school system's funding decreases, they are forced to do more with less. This frequently results in decreased student faculty ratios and increased class sizes. Many schools are also forced to cut funding for the arts and enrichment programs which may be vital to academic success. Additionally, with decreased budgets, access to specialty and advanced classes for students who show high potential frequently decreases. A less obvious consequence of financial difficulty is difficulty in attracting new teachers and staff, especially those who are experienced.[89] According to an article written in The Washington Post, students are reportedly taking 112 standardized tests over the course of K-12 with the most standardized tests per grade being tenth graders that take on average 11 standardized tests over one school year.[96] This became such a problem that in 2015 and 2016, the Department of Education put in action plans that would reduced the number of standardized tests that can be given as well as capping the percent of class time that can be dedicated to standardized tests at 2%. This amount of testing is still more than other countries like Finland that has less standardized tests but still far less than other countries like South Korea which not only has more standardized tests but they are also considered to be more rigorous.[citation needed]

Family resources

[edit]It has been shown that the socioeconomic status of the family has a large correlation with both the academic achievement and attainment of the student. "The income deficits for inner-city students is approximately $14,000 per year and $10,000 per year for the families of those living in the respective areas compared to the average income of families in suburban areas."[89][94]

We see more and more girls being taken out of school in South Asia to provide for their families through work. A frightening statistic is that over 12% of children in South Asia are engaged in child labor" (UNICEF).[97] Sadly, we see many children are out of school and uneducated but working for money to go back to their families. This is also a segway into the rise of child slavery and sex trafficking in Asia. The economy of certain areas may prove to be the reason more children are in or out of school, and we also see favor in the more well off communities in forms of educational resources. Employing children takes them out of school and it destroys their future opportunities and skills attained for their adult life, leaving them vulnerable to poverty and other poverty related issues.

Money can also have effects on whether a child finishes high school. In data given by the NCES, it was shown that 20% of students that were considered to be low income would drop out before they get to graduation while only 5% of middle income students will drop out. And only 3% of high income students would drop out.[98]

More well off sub-urban families can afford to spend money on their children's education in forms such as private schools, private tutoring, home lessons, and increased access to educational materials such as computers, books, educational toys, shows, and literature.[89] Kids from poorer families are shown to have lower average SAT scores with a difference of almost 400 points when comparing families with an annual income of $40,000 to families with an annual income of $200,000.[99]

Sub-urban families are also frequently able to provide larger amounts of social capital to their kids, such as increased use of "proper English", exposure to plays and museums, and familiarity with music, dance, and other such programs. Even more, inner-city students are more likely to come from single-parent homes and rural students are more likely to have siblings than their suburban peers decreasing the amount of investment per child their families are able to afford. This notion is called resource dilution which posits that families have finite levels of resources, such as time, energy, and money. When sibship (amount of siblings) increases, resources for each child become diluted.[100][89]

In college, the family's resources are even more important. In a study done by the National Center for Education Statistics, students were said to be more likely to attend college within 3 years of leaving high school just by thinking their family could financially support it.[clarification needed] The same study asked a large group of eleventh grade students if they wanted to go to college and 32% of students agreed that even if they did get accepted to college, they wouldn't go because their family could not afford it.[101]

Family values

[edit]The investment a family puts into their child's education is largely reflective of the value the parent puts on education. The value placed on education is largely a combination of the parent's education level and the visual returns on education in the community the family lives in.

Sub-urban families tend to have parents with a much larger amount of education than families in rural and inner-city locations. This allows sub-urban parents to have personal experience with returns on education as well as familiarity with educational systems and processes. In addition, parents can invest and transmit their own cultural capital to their children by taking them to museums, enrolling them in extra-curriculars, or even having educational items in the house. In contrast, parents from rural and urban areas tend to have less education and little personal experience with their returns. The areas they live in also put very little value on education and reduce the incentive to gain it. This leads to families that could afford to invest greater resources in their children's education not to.[89]

Gifted and talented education

[edit]There is a disproportionate percentage of middle and upper-class White students labeled as gifted and talented compared to lower-class, minority students.[28] Similarly, Asian American students have been over-represented in gifted education programs.[102] In 1992, African Americans were underrepresented in gifted education by 41%, Hispanic American students by 42%, and American Indians by 50%. Conversely, White students were over-represented in gifted education programs by 17% and Asian American minority students being labeled as gifted and talented, but research shows that there is a growing achievement gap between White students and non-Asian students of color. There is also a growing gap between gifted students from low-income backgrounds and higher-income backgrounds.[103]

The reasons for the under-representation of African-American, Hispanic-American, and American-Indian students in gifted and talented programs can be explained by recruitment issues/screening and identifying; and personnel issues.[102] Most states use a standardized achievement and aptitude test, which minority students have a history of performing poorly on, to screen and identify gifted and talented students. Arguments against standardized tests claim that they are culturally biased, favoring White students, require a certain mastery of the English language, and can lack cultural sensitivity in terms of format and presentation.[102] In regards to personnel issues, forty-six states use teacher nominations, but many teachers are not trained in identifying or teaching gifted students. Teachers also tend to have lower expectations of minority students, even if they are identified as gifted. 45 states allow for parental nominations, but the nomination form is not sensitive to cultural differences and minority parents can have difficulty understanding the form. Forty-two states allow self-nomination, but minority students tend not to self nominate because of social-emotional variables like peer pressure or feeling isolated or rejected by peers.[102] Additionally, some students are identified as gifted and talented simply because they have parents with the knowledge, political skills, and power to require schools to classify their child as gifted and talented. Therefore, providing their child with special instruction and enrichment.[28]

Special education

[edit]In addition to the unbalanced scale of gender disproportionality in formal education, students with "special needs" comprise yet another facet of educational inequality. Prior to the 1975 passing of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (currently known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)) approximately 2 million children with special needs were not receiving sufficient public education. Of those that were within the academic system, many were reduced to lower standards of teaching, isolated conditions, or even removal from school buildings altogether and relocated out of peer circulation.[104] The passing of this bill effectively changed the lives of millions of special needs students, ensuring that they have free access to quality public education facilities and services. And while there are those that benefit from the turning of this academic tide, there are still many students (most of which are minorities with disabilities) that find themselves in times of learning hardship due to the unbalanced distribution of special education funding.

In 1998 1.5 million minority children were identified with special learning needs in the US, out of that 876,000 were African American or Native American. African-American students were three times as likely to be labeled as special needs than that of Caucasians. Students who both are special education students and of a minority face unequal chances for quality education to meet their personal needs. Special education referrals are, in most cases in the hands of the general education teacher, this is subjective and because of differences, disabilities can be overlooked or unrecognized. Poorly trained teachers at minority schools, poor school relationships, and poor parent-to-teacher relationships play a role in this inequality. With these factors, minority students are at a disadvantage because they are not given the appropriate resources that would in turn benefit their educational needs.[104]

US Department of Education data shows that in 2000–2001 at least 13 states exhibited more than 2.75% of African-American students enrolled in public schools with the label of "mental retardation". At that time national averages of Caucasians labeled with the same moniker came in at 0.75%. During this period no Individual state rose over 2.32% of Caucasian students with special needs.[104]

According to Tom Parrish, a senior research analyst with the American Institutes for Research, African-American children are 2.88 times more likely to be labeled as "mentally retarded", and 1.92 times more likely to be labeled as emotionally disturbed than Caucasian children. This information was calculated by data gathered from the US Department of Education.[104]

Researchers Edward Fierros and James Conroy, in their study of district-level data regarding the issue of minority over-representation, have suggested that many states may be mistaken with their current projections and that disturbing minority-based trends may be hidden within the numbers. According to the Individuals with Disabilities Act students with special needs are entitled to facilities and support that cater to their individual needs, they should not be automatically isolated from their peers or from the benefits of general education. However, according to Fierros and Conroy, once minority children such as African Americans and Latinos are labeled as students with special needs they are far less likely than Caucasians to be placed in settings of inclusive learning and often receive less desirable treatment overall.[104]

History of educational oppression

[edit]United States

[edit]The historical relationships in the United States between privileged and marginalized communities play a major role in the administering of unequal and inadequate education to these socially excluded communities. The belief that certain communities in the United States were inferior in comparison to others has allowed these disadvantages to foster into the great magnitude of educational inequality that we see apparent today.

For African Americans, deliberate systematic education oppression dates back to enslavement, more specifically in 1740. In 1740, North Carolina passed legislation that prohibited slave education. While the original legislature prohibited African Americans from being taught how to write, as other States adopted their own versions of the law, southern anti-literacy legislatures banned far more than just writing. Varying Southern laws prohibited African Americans from learning how to read, write, and assembling without the presence of slave owners. Many states as far as requiring free African Americans to leave in fear of them educating their enslaved brethren. By 1836, the public education of all African-Americans was strictly prohibited.

The enslavement of African Americans removed the access to education for generations.[105] Once the legal abolishment of slavery was enacted, racial stigma remained. Social, economic, and political barriers held Blacks in a position of subordination.[14] Although legally African Americans had the ability to be learning how to read and write, they were often prohibited from attending schools with White students. This form of segregation is often referred to as de jure segregation.[106] The schools that allowed African-American students to attend often lacked financial support, thus providing inadequate educational skills for their students. Freedmen's schools existed but they focused on maintaining African Americans in servitude, not enriching academic prosperity.[105] The United States then experienced legal separation in schools between Whites and Blacks. Schools were supposed to receive equal resources but there was an undoubted inequality. It was not until 1968 that Black students in the South had universal secondary education.[105] Research reveals that there was a shrinking of inequality between racial groups from 1970 to 1988, but since then the gap has grown again.[1][105]

Latinos and American Indians experienced similar educational repression in the past, which effects are evident now. Latinos have been systematically shut out of educational opportunities at all levels. Evidence suggests that Latinos have experienced this educational repression in the United States as far back as 1848.[105] Despite the fact that it is illegal to not accept students based on their race, religion, or ethnicity, in the Southwest of the United States Latinos were often segregated through the deliberate practice of school and public officials. This form of segregation is referred to as de facto segregation.[106] American Indians experienced the enforcement of missionary schools that emphasized the assimilation into White culture and society. Even after "successful" assimilation, those American Indians experienced discrimination in White society and often rejected by their tribe.[105] It created a group that could not truly benefit even if they gained an equal education.

American universities are separated into various classes, with a few institutions, such as the Ivy League schools, much more exclusive than the others. Among these exclusive institutions, educational inequality is extreme, with only 6% and 3% of their students coming from the bottom two income quintiles.[107]

Resources

[edit]Access to resources plays an important role in educational inequality. In addition to the resources from the family mentioned earlier, access to proper nutrition and health care influences the cognitive development of children.[15] Children who come from poor families experience this inequality, which puts them at a disadvantage from the start. Not only important are resources students may or may not receive from family, but schools themselves vary greatly in the resources they give their students. On 2 December 2011, the U.S. Department of Education released that school districts are unevenly distributing funds, which are disproportionately underfunding low-income students.[108] This is holding back money from the schools that are in great need. High poverty schools have less-qualified teachers with a much higher turnover rate.[3] In every subject area, students in high poverty schools are more likely than other students to be taught by teachers without even a minor in their subject matter.[9]

Better resources allow for the reduction of classroom size, which research has proven improves test scores.[15] It also increases the number of after school and summer programs—these are very beneficial to poor children because it not only combats the increased loss of skill over the summer but keeps them out of unsafe neighborhoods and combats the drop-out rate.[15] There is also a difference in the classes offered to students, specifically advanced mathematics and science courses. In 2012, Algebra II was offered to 82% of the schools (in diverse districts) serving the fewest Hispanic and African-American students, while only 65% of the schools serving the most African-American and Hispanic students offered students the same course. Physics was offered to 66% of the schools serving the fewest Hispanic and African-American students, compared to 40% serving the most. Calculus was offered to 55% of the schools serving the fewest Hispanic and African-American students, compared to 29% serving the most.[34]

This lack of resources is directly linked to ethnicity and race. Black and Latino students are three times more likely than Whites to be in high poverty schools and twelve times as likely to be in schools that are predominantly poor.[3] Also, in schools that are composed of 90% or above of minorities, only one half of the teachers are certified in the subjects they teach.[9] As the number of White students increases in a school, funding tends to increase as well.[105] Teachers in elementary schools serving the most Hispanic and African-American students are paid on average $2250 less per year than their colleagues in the same district working at schools serving the fewest Hispanic and African-American students.[34] From the family resources side, 10% of White children are raised in poverty, while 37% of Latino children are and 42% of African-American children are.[16] Research indicates that when resources are equal, Black students are more likely to continue their education into college than their White counterparts.[109]

State conflicts

[edit]Within fragile states, children may be subject to inadequate education. The poor educational quality within these states is believed to be a result of four main challenges. These challenges include coordination gaps between the governmental actors, the policy maker's low priority on educational policy, limited financing, and lack of educational quality.[110]

Measurement

[edit]In the last decade, various tests have been administered throughout the world to gather information about students, the schools they attend, and their educational achievements. These tests include the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's Programme for International Student Assessment and the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement's Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. To calculate the different test parameters in each country and calculate a standard score, the scores of these tests are put through item response theory models. Once standardized, analysts can begin looking at education through the lens of achievement rather than looking at attainment. Through looking at achievement, the analysts can objectively examine educational inequality throughout the globe.[111]

Besides the use of achievement, analysts are able to use a few other methods, including but not exclusive to the Living Standard Measurement Study and the Index of Regional Education Advantage. China implemented the IREA to better understand regional differences from East to West in their country over a period of three years while Albania took a look at individual households to better understand their education differences.

Albania Educational Inequality Study

[edit]In an effort to better understand home welfare, the World Bank Organization has created a Living Standard Measurement Study program that helps analyze poverty in developing countries and allows for utilization in various empirical analysis studies. A study done by Nathalie Picard and Francois Wolff in Albania utilized the LSMS framework to further their study into educational inequalities within Albania. With the data presented from the LSMS models, Picard and Wolff were able to use empirical methods to determine that nearly 40% of educational differences in the country were due to household differences between families.[112] The LSMS framework is composed of household and individual well being questions that assess the welfare state of the house. Data for various regions can be viewed on their public website.[113] Within the survey are questions related to educational background that help the analytics team better relate the household state and region to the existing education levels. Through the Albania study, Picard and Wolff were able to utilize these statistics to help illustrate the educational levels between various households and different income levels in Albania. This practice can be implemented in many locations worldwide.

China Regional Educational Inequality Study

[edit]China incorporated an index called the Index of Regional Education Advantage or IREA to help analyze the effects that new policies had on their countries education system throughout their various regions. This multidimensional index includes a higher comprehensive list of dimensions than the Gini index in relation to education and therefore brings a greater understanding of the disparities in education. Founding off three core values of provision, enrollment, and attainment within the education system the IREA index is able to utilize conversion factors to create a capability set to diagnose the education levels of their different regions.[114] Since all three are not independent variables it is critical to utilize items like geometric means when calculating values like enrollment and attainment. Due to the IREA being a composite summary index it is common to utilize weighted indicators to show importance of each core value.[114] When evaluating the finalized scores of the regions China produced spatial pattern diagrams with data over three years to reflect any changes over the associated time period. The scores give a visual of the regional inequalities in their education. A change to a darker color indicated that the education had worsened in score. This comprehensive IREA score reflects the true condition of the area in question.[114]

Effects

[edit]Social mobility

[edit]Social mobility refers to the movement in class status from one generation to another. It is related to the "rags to riches" notion that anyone, with hard work and determination, has the ability to move upward no matter what background they come from. Contrary to that notion, however, sociologists and economists have concluded that, although exceptions are heard of, social mobility has remained stagnant and even decreased over the past thirty years.[115] From 1979 through 2007 the wage income for lower- and middle-class citizens has risen by less than 17 percent while the one percent has grown by approximately 156 percent sharply contrasting the "postwar period up through the 1970s when income growth was broadly shared".[116]

Some of the decreases in social mobility may be explained by the stratified educational system. Research has shown that since 1973, men and women with at least a college degree have seen an increase in hourly wages, while the wages for those with less than a college degree have remained stagnant or have decreased during the same period of time.[117] Since the educational system forces low-income families to place their children into less-than-ideal school systems, those children are typically not presented with the same opportunities and educational motivation as are students from well-off families, resulting in patterns of repeated intergenerational educational choices for parent and child, also known as decreased or stagnant social mobility.[115]

Remedies

[edit]There are a variety of efforts by countries to assist in increasing the availability of quality education for all children.

Assessment

[edit]Based on input from more than 1,700 individuals in 118 countries, UNESCO and the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution have co-convened the Learning Metrics Task Force.[118] The task force aims to shift the focus from access to access plus learning.[118] They discovered through assessment, the learning and progress of students in individual countries can be measured.[118] Through the testing, governments can assess the quality of their education programs, refine the areas that need improvement, and ultimately increase their student's success.[118]

Education for All Act

[edit]The Education For All act or EFA is a global commitment to provide quality basic education for all children, youth, and adults. In 2000, 164 governments pledged to achieve education for all at the World Education Forum. There are six decided-upon goals designed to reach the goal of Education for All by 2015. The entities working together to achieve these goals include governments, multilateral and development agencies, civil society, and the private sector. UNESCO is responsible for coordinating the partnerships. Although progress has been made, some countries are providing more support than others. Also, there is a need to strengthen overall political commitment as well as strengthening the needed resources.[119]

Global Partnership for Education

[edit]Global Partnership for Education, or GPE, functions to create a global effort to reduce educational inequality with a focus on the poorest countries. GPE is the only international effort with its particular focus on supporting countries' efforts to educate their youth from primary through secondary education. The main goals of the partnership include providing educational access to each child, ensuring each child masters basic numeracy and literacy skills, increasing the ability for governments to provide quality education for all, and providing a safe space for all children to learn in. They are a partnership of donor and developing countries but the developing countries shape their own educational strategy based upon their personal priorities. When constructing these priorities, GPE serves to support and facilitate access to financial and technical resources. Successes of GPE include helping nearly 22 million children get to school, equipping 52,600 classrooms, and training 300,000 teachers.[120]

Massive online classes

[edit]There is a growing shift away from traditional higher education institutions to massive open online courses (MOOC). These classes are run through content sharing, videos, online forums, and exams. The MOOCs are free which allows for many more students to take part in the classes, however, the programs are created by global north countries, therefore inhibiting individuals in the global south from creating their own innovations.[121]

Trauma-informed education

[edit]Trauma-informed education is a pedagogical approach that acknowledges the impacts of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on a child's learning and behavior. The efficacy of trauma-informed approaches has been studied in a variety of settings, including communities in areas that have experienced natural disasters, terrorism or political instability, students of refugee or asylum status, and students who are marginalized as a result of language, ethnicity or culture. ACEs are associated with poorer attendance at school, educational attainment, and worse mental health outcomes.[122] Trauma-informed education has been termed a social justice imperative by some academics owing to the disproportionate impact of childhood trauma on marginalized communities including low-income communities, communities of color, sexual and gender minorities, and immigrants.[123]

The expansion of the definition of trauma as encompassing interpersonal forms of violence and perceived threat or harm, especially in the experiences of vulnerable and marginalized communities was formally recognized by the U.S.-based Center for Substance Abuse Treatment in 2014.[124] Thereafter, the adoption of trauma-informed approaches in public service provisions including education has led to developing practices and policies that take trauma histories into consideration.

In 2016, the American Institutes for Research published a trauma-informed care curriculum centered around five domains - supporting staff development, creating a safe and supportive environment, assessing needs and planning services, involving consumers, and adapting practices. Similarly, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network defines a trauma-sensitive approach as:[125]

- "Realizing the widespread impact of trauma and pathways to recovery

- Recognizing traumas signs and symptoms

- Responding by integrating knowledge about trauma into all facets of the system

- Resisting re-traumatization of trauma-impacted individuals by decreasing the occurrence of unnecessary triggers (i.e., trauma and loss reminders) and by implementing trauma-informed policies, procedures, and practices."

A number of barriers to the implementation of trauma-informed approaches have been identified, including communication gaps between providers and parents, stigmatization of mental health concerns, lack of supportive school environments and competing teacher responsibilities.[126]

Policy implications

[edit]With the knowledge that early educational intervention programs, such as extended childcare during preschool years, can significantly prepare low-income students for educational and life successes, comes a certain degree of responsibility. One policy change that seems necessary to make is that quality child care is available to every child in the United States at an affordable rate. This has been scientifically proven to push students into college, and thus increase social mobility. The ultimate result of such a reality would be that the widely stratified educational system that exists in the U.S. today would begin to equalize so that every child born, regardless of socioeconomic status, would have the same opportunity to succeed. Many European countries are already exercising such successful educational systems.

Based on historical evidence, an increase in general schooling not only improves numeracy and literacy skills in the population overall, but also tends to result in a narrowing the educational gender gap.[127]

Global evidence

[edit]

Albania

[edit]Household income in Albania is very low. Many families are unable to provide a college education for their kids, with the money they make. Albania is one of the poorest countries in Europe with a large population of people under the age of 25. This population of students needs a path to higher education. Nothing is being done for all the young adults who are smart enough to go to college but cannot afford to.

Bangladesh

[edit]The Bangladesh education system includes more than 100,000 schools run by public, private, NGO, and religious providers.[128] The schools are overseen by a national ministry. Their system is centralized and overseen by the sub-districts also known as upazilas.[128] During the past two decades, the system expanded through new national policies and pro-poor spending. The gross enrollment rate in the poorest quintile of upazilas is 101 percent.[128] Also, the poorest quintile spending per child was 30 percent higher than the wealthiest quintile.[128]

Educational inequalities continue despite the increased spending. They do not have consistent learning outcomes across the upazilas. In almost 2/3 of upazilas, the dropout rate is over 30 percent.[128] They have difficulty acquiring quality teachers and 97 percent of preprimary and primary students are in overcrowded classrooms.[128]

India

[edit]According to the 2011 census of India, the literacy rate for males was 82%, as compared to the literacy rate of 65% for females. Despite the provisions of the Right to Education, 40% of girls between the ages of 15 and 18 are out of school, primarily to either supplement family income in the informal sector, or to work within the household.[129] It is estimated that up to 23% of girls leave school at the onset of puberty due to the stigmatization of menstruation, lack of access to menstrual products and sanitation.[130] Menstrual inequity is also a leading cause of absenteeism.

The Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan, set up by the Indian central government in 2021 to improve access to education, saw an increase in the Gross Enrollment Ratio among girls across all school levels. This scheme has sanctioned 5,627 Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalayas, residential schools for girls from disadvantaged communities.[131]

Urban areas have historically reported higher rates of literacy. In 2018, rural areas had a literacy rate of 73.5%, as compared to the urban literacy rate of 87.7 per cent. Although 83% of the total schools are located in rural India,[132] learning outcomes and dropout rates remain disproportionately high. This has been attributed to high rural poverty rates and lack of quality teaching.[133]

Educational inequalities are also exacerbated by the caste system. In the 2011 census, Scheduled Castes had an average literacy rate of 66.1 per cent with an all-India literacy rate of 73 per cent.[134]

Under the National Education Policy 2020, marginalized gender identities, sociocultural identities, geographical identities, disabilities, and socioeconomic conditions have been grouped under Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Groups (SEDGs). Specific provisions have been recommended for SEDGs including targeted scholarships, conditional cash transfers to parents, and providing bicycles for transportation.[135]

South Africa

[edit]Inequality in higher education

[edit]Africa, in general, has suffered from decreased spending on higher education programs. As a result, they are unable to obtain moderate to high enrollment and there is minimal research output.[121]

Within South Africa, there are numerous factors that affect the quality of tertiary education. The country inherited class, race, and gender inequality in the social, political, and economic spheres during the Apartheid. The 1994 constitution emphasizes higher education as useful for human resource development and of great importance to any economic and social transitions. However, they are still fighting to overcome the colonialism and racism in intellectual spaces.[121]

Funding from the government has a major stake in the educational quality received. As a result of declining government support, the average class size in South Africa is growing. The increased class size limits student–teacher interactions, therefore further hindering students with low problem solving and critical thinking skills. In an article by Meenal Shrivastava and Sanjiv Shrivastava, the argument is made that in large class sizes "have ramifications for developing countries where higher education where higher education is a core element in the economic and societal development". These ramifications are shown to include lower student performance and information retention.[121]

United Kingdom