Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

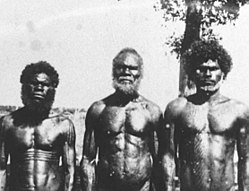

Aboriginal Australians

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia 50,000 to 65,000 years ago, and over time formed as many as 500 linguistic and territorial groups.[3] In the past, Aboriginal people lived over large sections of the continental shelf. They were isolated on many of the smaller offshore islands and Tasmania when the land was inundated at the start of the Holocene inter-glacial period, about 11,700 years ago. Despite this, Aboriginal people maintained extensive networks within the continent and certain groups maintained relationships with Torres Strait Islanders and the Makassar people of modern-day Indonesia.

Over the millennia, Aboriginal people developed complex trade networks, inter-cultural relationships, law and religions,[3][4] which make up some of the oldest continuous cultures in the world.[5] At the time of European colonisation of Australia, the Aboriginal people spoke more than 250 different languages,[6] possessed varying degrees of technology, and lived in various types of settlements. Languages (or dialects) and language-associated groups of people are connected with stretches of territory known as "Country", with which they have a profound spiritual connection.

Contemporary Aboriginal beliefs are shaped by traditional beliefs, the disruption of colonisation, religions brought to the continent by later migrants, and contemporary issues.[7][8][9] Just over half hold secular or other spiritual beliefs or no religious affiliation; about 40% are Christian; and about 1% adhere to a traditional Aboriginal religion.[10] Traditional cultural beliefs are passed down and shared through dancing, stories, songlines, and art that collectively weave an ontology of modern daily life and ancient creation known as the Dreaming.

Studies of Aboriginal groups' genetic makeup are ongoing, but evidence suggests that they have genetic inheritance from ancient Asian peoples. Aboriginal Australians and Papuans shared the same paleocontinent Sahul, but became genetically distinct about 37,000 years ago.[11] Aboriginal Australians have a broadly shared, complex genetic history, but only in the last 200 years have they been defined by others as, and started to self-identify as, a single group. Aboriginal identity has changed over time and place, with family lineage, self-identification, and community acceptance all of varying importance.

The 2021 census shows that there were over 944,000 Aboriginal people, comprising 3.7% of Australia's population.[1][note 1] Over 80% of Aboriginal people today speak English at home, and about 77,000 speak an Indigenous language at home. Aboriginal people, along with Torres Strait Islander people, suffer a number of severe health and economic deprivations in comparison with the wider Australian community.

Origins

[edit]Archeological evidence indicates that the ancestors of today's Aboriginal Australians first migrated to the continent 50,000 to 65,000 years ago.[13][14][15][16] Genomic studies suggest that the peopling of Australia happened between 43,000 and 60,000 years ago.[17][18][19][20]

Early human migration to Australia was achieved when it formed a part of the Sahul continent, connected to the island of New Guinea via a land bridge.[21] This would have nevertheless required crossing the sea at the Wallace Line.[22] It is also possible that people came by island-hopping via an island chain between Sulawesi and New Guinea, reaching North Western Australia via Timor.[23] As sea levels rose, the people on the Australian mainland and nearby islands became increasingly isolated, some on Tasmania and some of the smaller offshore islands when the land was inundated at the start of the Holocene, the inter-glacial period that started about 11,700 years ago.[24]

A 2021 study by researchers at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage has mapped the likely migration routes of the peoples as they moved across the Australian continent to its southern reaches of what is now Tasmania (then part of the mainland). The modelling is based on data from archaeologists, anthropologists, ecologists, geneticists, climatologists, geomorphologists, and hydrologists. The new models suggest that the first people may have landed in the Kimberley region in what is now Western Australia about 60,000 years ago, and had settled across the continent within 6,000 years.[25][26]

Aboriginal Australians may have one of the oldest continuous cultures on earth.[27] In Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, oral histories comprising complex narratives have been passed down by Yolngu people through hundreds of generations. The Aboriginal rock art, dated by modern techniques, shows that their culture has continued from ancient times.[28]

Genetics

[edit]Genetic studies have revealed that a population wave, termed East Eurasian Core, outgoing from the Iranian plateau during the Initial Upper Paleolithic period populated the Asia-Pacific region via a southern route dispersal. This wave is suggested to have expanded into the South and Southeast Asia region and subsequently diverged rapidly into the ancestors of Ancient Ancestral South Indians (AASI), Andamanese, East Asians, and Australasians, including Aboriginal Australians and Papuans.[29][30][31][32] Aboriginal Australians are genetically most closely related to other Oceanians, such as Papuans and Melanesians, who are collectively referred to as "Australasians" and which can be described as "a deeply branching East Asian lineage".[29][30][32][33][31]

While the commonly accepted date for the diversification of modern humans following the Out of Africa migration is placed at 60–50,000 years ago, there is, however, evidence that Aboriginal Australians may carry ancestry from an earlier human diaspora (xOoA) that originated 75,000 to 62,000 years ago. This earlier group has been estimated to have possibly contributed around 2% ancestry to modern Aboriginal Australians.[34][35]

Mallick et al. 2016 and Mark Lipson et al. 2017 found the bifurcation of Eastern Eurasians and Western Eurasians dates to at least 45,000 years ago, with indigenous Australians nested inside the Eastern Eurasian clade.[36][32] Aboriginal Australians, together with Papuans, may either form a sister clade to a single mainland Asian clade consisting of the AASI, Andamanese and East Asians, and to the exclusion of West Eurasians,[37] or alternatively are nested within the Eastern Eurasian cluster without a strong internal cladal structure against mainland Asian lineages.[32]

Genetic data on indigenous populations of Borneo and Malaysia showed them to be closer related to other mainland Asian groups, than compared to the groups from Papua New Guinea and Australia. This indicates that populations in Australia were isolated for a long time from the rest of Southeast Asia. They remained untouched by migrations and population expansions into that area, which can be explained by the Wallace line.[38]

Uniparentals

[edit]The most common Y-chromosome haplogroups among Aboriginal Australians is C1b2, followed by haplogroups S and M; these latter haplogroups are also very frequent among Papuans.[39]

Other studies

[edit]In a 2001 study, blood samples were collected from some Warlpiri people in the Northern Territory to study their genetic makeup (which is not representative of all Aboriginal peoples in Australia). The study concluded that the Warlpiri are descended from ancient Asians whose DNA is still somewhat present in Southeastern Asian groups, although greatly diminished. The Warlpiri DNA lacks certain information found in modern Asian genomes, and carries information not found in other genomes. This reinforces the idea of ancient Aboriginal isolation.[38]

Genetic data extracted in 2011 by Morten Rasmussen et al., who took a DNA sample from an early-20th-century lock of an Aboriginal person's hair, found that the Aboriginal ancestors probably migrated through South Asia and Maritime Southeast Asia, into Australia, where they stayed. As a result, outside of Africa, the Aboriginal peoples have occupied the same territory continuously longer than any other human populations. These findings suggest that modern Aboriginal Australians are the direct descendants of the eastern wave, who left Africa up to 75,000 years ago.[40][41]

The Rasmussen study also found evidence that Aboriginal peoples carry some genes associated with the Denisovans (a species of human related to but distinct from Neanderthals) of Asia; the study suggests that there is an increase in allele sharing between the Denisovan and Aboriginal Australian genomes, compared to other Eurasians or Africans. Examining DNA from a finger bone excavated in Siberia, researchers concluded that the Denisovans migrated from Siberia to tropical parts of Asia and that they interbred with modern humans in Southeast Asia 44,000 years BP, before Australia separated from New Guinea approximately 11,700 years BP. They contributed DNA to Aboriginal Australians and to present-day New Guineans and an indigenous tribe in the Philippines known as Mamanwa. This study confirms Aboriginal Australians as one of the oldest living populations in the world. They are possibly the oldest outside Africa, and they may have the oldest continuous culture on the planet.[42]

A 2016 study at the University of Cambridge suggests that it was about 50,000 years ago that these peoples reached Sahul (the supercontinent consisting of present-day Australia and its islands and New Guinea). The sea levels rose and isolated Australia about 10,000 years ago, but Aboriginal Australians and Papuans diverged from each other genetically earlier, about 37,000 years BP, possibly because the remaining land bridge was impassable. This isolation makes the Aboriginal people the world's oldest culture. The study also found evidence of an unknown hominin group, distantly related to Denisovans, with whom the Aboriginal and Papuan ancestors must have interbred, leaving a trace of about 4% in most Aboriginal Australians' genome. There is, however, increased genetic diversity among Aboriginal Australians based on geographical distribution.[43][11]

Carlhoff et al. 2021 analysed a Holocene hunter-gatherer sample ("Leang Panninge") from South Sulawesi, which shares high amounts of genetic drift with Aboriginal Australians and Papuans. This suggests that a population split from the common ancestor of Aboriginal Australians and Papuans. The sample also shows genetic affinity with East Asians and the Andamanese people of South Asia. The authors note that this hunter-gatherer sample can be modelled with ~50% Australian/Papuan-related ancestry and either with ~50% East Asian or Andamanese Onge ancestry, highlighting the deep split between Leang Panninge and Aboriginal/Papuans.[44][note 2]

Two genetic studies by Larena et al. 2021 found that Philippines Negrito people split from the common ancestor of Aboriginal Australians and Papuans before the latter two diverged from each other, but after their common ancestor diverged from the ancestor of East Asian peoples.[45][46][47]

Changes about 4,000 years ago

[edit]The dingo reached Australia about 4,000 years ago. Near that time, there were changes in language (with the Pama-Nyungan language family spreading over most of the mainland), and in stone tool technology. Smaller tools were used. Human contact has thus been inferred, and genetic data of two kinds have been proposed to support a gene flow from India to Australia: firstly, signs of South Asian components in Aboriginal Australian genomes, reported on the basis of genome-wide SNP data; and secondly, the existence of a Y chromosome (male) lineage, designated haplogroup C∗, with the most recent common ancestor about 5,000 years ago.[48]

The first type of evidence comes from a 2013 study by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology using large-scale genotyping data from a pool of Aboriginal Australians, New Guineans, island Southeast Asians, and Indians. It found that the New Guinea and Mamanwa (Philippines area) groups diverged from the Aboriginal about 36,000 years ago (there is supporting evidence that these populations are descended from migrants taking an early "southern route" out of Africa, before other groups in the area).[citation needed] Also the Indian and Australian populations mixed long before European contact, with this gene flow occurring during the Holocene (c. 4,200 years ago).[49] The researchers had two theories for this: either some Indians had contact with people in Indonesia who eventually transferred those Indian genes to Aboriginal Australians, or a group of Indians migrated from India to Australia and intermingled with the locals directly.[50][51]

However, a 2016 study in Current Biology by Anders Bergström et al. excluded the Y chromosome as providing evidence for recent gene flow from India into Australia. The study authors sequenced 13 Aboriginal Australian Y chromosomes using recent advances in gene sequencing technology. They investigated their divergence times from Y chromosomes in other continents, including comparing the haplogroup C chromosomes. They found a divergence time of about 54,100 years between the Sahul C chromosome and its closest relative C5, as well as about 54,300 years between haplogroups K*/M and their closest haplogroups R and Q. The deep divergence time of 50,000-plus years with the South Asian chromosome and "the fact that the Aboriginal Australian Cs share a more recent common ancestor with Papuan Cs" excludes any recent genetic contact.[48]

The 2016 study's authors concluded that, although this does not disprove the presence of any Holocene gene flow or non-genetic influences from South Asia at that time, and the appearance of the dingo does provide strong evidence for external contacts, the evidence overall is consistent with a complete lack of gene flow, and points to indigenous origins for the technological and linguistic changes. They attributed the disparity between their results and previous findings to improvements in technology; none of the other studies had utilised complete Y chromosome sequencing, which has the highest precision. For example, use of a ten Y STRs method has been shown to massively underestimate divergence times. Gene flow across the island-dotted 150-kilometre-wide (93 mi) Torres Strait, is both geographically plausible and demonstrated by the data, although at this point it could not be determined from this study when within the last 10,000 years it may have occurred—newer analytical techniques have the potential to address such questions.[48]

Bergstrom's 2018 doctoral thesis looking at the population of Sahul suggests that other than relatively recent admixture, the populations of the region appear to have been genetically independent from the rest of the world since their divergence about 50,000 years ago. He writes "There is no evidence for South Asian gene flow to Australia .... Despite Sahul being a single connected landmass until [8,000 years ago], different groups across Australia are nearly equally related to Papuans, and vice versa, and the two appear to have separated genetically already [about 30,000 years ago]."[52]

Environmental adaptations

[edit]

Aboriginal Australians possess inherited abilities to adapt to a wide range of environmental temperatures in various ways. A study in 1958 comparing cold adaptation in the desert-dwelling Pitjantjatjara people compared with a group of European people showed that the cooling adaptation of the Aboriginal group differed from that of the white people, and that they were able to sleep more soundly through a cold desert night.[53] A 2014 Cambridge University study found that a beneficial mutation in two genes which regulate thyroxine, a hormone involved in regulating body metabolism, helps to regulate body temperature in response to fever. The effect of this is that the desert people are able to have a higher body temperature without accelerating the activity of the whole of the body, which can be especially detrimental in childhood diseases. This helps protect people to survive the side-effects of infection.[54][55]

Population growth and location

[edit]Based on the 2021 census, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates there were 901,655 Aboriginal Australians, and 42,515 who identified as both Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander. These groups comprise 3.7% of the total Australian population. About 39,540 people identified as Torres Strait Islander, which is a different ethnic group from Aboriginal Australian.[56]

| Census | Number of persons | Intercensal change (number) | Intercensal change (percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 455,028 | 45,025 | 11.0 |

| 2011 | 548,368 | 93,340 | 20.5 |

| 2016 | 649,171 | 100,803 | 18.4 |

| 2021 | 812,728 | 163,557 | 25.2 |

| *These are initial counts and differ from the final estimates which adjust for undercounting.[56][57] | |||

Based on initial 2021 census counts, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander population grew 25.2%, since the previous census in 2016.[57] Demographic factors – births, deaths and migration[note 3] – accounted for 43.5% of the increase (71,086 people). In turn, 76.2% of that increase was attributed to people aged 0–19 years in 2021, broken down as 52.5% for 0–4 year olds (births since 2016) and 23.7% for 5–19 year olds.[57]

Reasons for the increase in Aboriginal population also include non-demographic factors. These include changes in individuals' identification as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander in different censuses, and individuals completing a census form in 2021 but not in 2016. These factors accounted for 56.5% of the increase in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. The increase was higher than observed between 2011 and 2016 (39.0%) and 2006–2011 (38.7%).[57]

The distribution of the Aboriginal Australian population (including those who identify as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) by state and territory is: New South Wales (35.3%), Queensland (26.3%), Western Australia (12.5%), Victoria (8.1%), Northern Territory (8.0%), South Australia (5.4%), Tasmania (3.4%) and Australian Capital Territory (1.0%).[58]

Indigenous Australians (including Torres Strait Islanders) are less likely to live in the major Australian cities than are non-Indigenous Australians (41% compared with 73%). They are more likely to live in remote or very remote areas (15% compared with 1.4%)[58]

Languages

[edit]Although humans arrived in Australia 50,000 to 65,000 years ago,[59][60] it is possible that the ancestor language of existing Aboriginal languages is as recent as 12,000 years old.[61] Over 250 Australian Aboriginal languages are thought to have existed at the time of first European contact.[62]

As of 2021, 84% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders spoke only English at home.[63] The National Indigenous Languages Survey (NILS) for 2018-19 found that more than 120 Indigenous language varieties were in use or being revived, although 70 of those in use are endangered.[64] The 2021 census found that 167 Indigenous languages were spoken at home by 76,978 Indigenous Australians.[65] NILS and the Australian Bureau of Statistics use different classifications for Indigenous Australian languages.[66]

According to the 2021 census, the classifiable Aboriginal languages with the most speakers are Kriol (7,403), Djambarrpuyngu (3,839), Pitjantjatjara (3,399), Warlpiri (2,592), Murrinh Patha (2,063) and Tiwi (2,053). There were also over 10,000 people who spoke an Indigenous language which could not be further defined or classified.[67]

Creoles

[edit]A number of English-based creoles have arisen in Australia after European contact, of which Kriol is among the strongest and fastest-growing Aboriginal languages. Kriol is spoken in the Northern Territory and Western Australia. It is estimated that there are 20,000 to 30,000 speakers of Indigenous creole languages.[68]

Tasmanian languages

[edit]Before British colonisation, there were perhaps five to sixteen languages on Tasmania,[69] possibly related to one another in four language families.[70] The last speaker of a traditional Tasmanian language, Fanny Cochrane Smith, died in 1905.[71] Palawa kani is an in-progress constructed language, built from a composite of surviving words from various Tasmanian Aboriginal languages.[72]

Indigenous sign languages

[edit]Traditional Indigenous languages often incorporated sign systems to aid communication with the hearing impaired, to complement verbal communication, and to replace verbal communication when the spoken language was forbidden for cultural reasons. Many of these sign systems are still in use.[73]

Groups and sub-groups

[edit]Dispersing across the Australian continent over time, the ancient people expanded and differentiated into distinct groups, each with its own language and culture.[74] More than 400 distinct Australian Aboriginal peoples have been identified, distinguished by names designating their ancestral languages, dialects, or distinctive speech patterns.[75] According to noted anthropologist, archaeologist and sociologist Harry Lourandos, historically, these groups lived in three main cultural areas, the Northern, Southern and Central cultural areas. The Northern and Southern areas, having richer natural marine and woodland resources, were more densely populated than the Central area.[74]

Geographically-based names

[edit]There are various other names from Australian Aboriginal languages commonly used to identify groups based on geography, known as demonyms, including:

- Anangu in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory

- Goorie (variant pronunciation and spelling of Koori) in South East Queensland and some parts of northern New South Wales

- Koori (or Koorie) in New South Wales and Victoria (Aboriginal Victorians)

- Murri in Central and Northern Queensland, sometimes referring to all Aboriginal Queenslanders

- Nunga in southern South Australia

- Noongar in southern Western Australia

- Palawah (or Pallawah) in Tasmania

- Tiwi on Tiwi Islands off Arnhem Land (NT)

A few examples of sub-groups

[edit]Other group names are based on the language group or specific dialect spoken. These also coincide with geographical regions of varying sizes. A few examples are:

- Anindilyakwa on Groote Eylandt (off Arnhem Land), NT

- Arrernte in central Australia[76]

- Bininj in Western Arnhem Land (NT)[77]

- Gunggari in south-west Queensland[78]

- Muruwari people in New South Wales

- Luritja (Kukatja), an Anangu sub-group based on language

- Ngunnawal in the Australian Capital Territory and surrounding areas of New South Wales

- Pitjantjatjara, an Anangu sub-group based on language

- Wangai in the Western Australian Goldfields

- Warlpiri (Yapa) in western central Northern Territory

- Yamatji in central Western Australia

- Yolngu in eastern Arnhem Land (NT)

Difficulties defining groups

[edit]However, these lists are neither exhaustive nor definitive, and there are overlaps. Different approaches have been taken by non-Aboriginal scholars in trying to understand and define Aboriginal culture and societies, some focusing on the micro-level (tribe, clan, etc.), and others on shared languages and cultural practices spread over large regions defined by ecological factors. Anthropologists have encountered many difficulties in trying to define what constitutes an Aboriginal people/community/group/tribe, let alone naming them. Knowledge of pre-colonial Aboriginal cultures and societal groupings is still largely dependent on the observers' interpretations, which were filtered through colonial ways of viewing societies.[79]

Some Aboriginal peoples identify as one of several saltwater, freshwater, rainforest or desert peoples.

Aboriginal identity

[edit]Terminology

[edit]The term Aboriginal Australians includes many distinct peoples who have developed across Australia for over 50,000 years.[80][81] These peoples have a broadly shared, though complex, genetic history,[82][51] but it is only in the last two hundred years that they have been defined and started to self-identify as a single group, socio-politically.[83][84] While some preferred the term Aborigine to Aboriginal in the past, as the latter was seen to have more directly discriminatory legal origins,[83] use of the term Aborigine has declined in recent decades, as many consider the term an offensive and racist hangover from Australia's colonial era.[85][86]

The definition of the term Aboriginal has changed over time and place, with family lineage, self-identification and community acceptance all being of varying importance.[87][88][89]

The term Indigenous Australians refers to Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the term is conventionally only used when both groups are included in the topic being addressed, or by self-identification by a person as Indigenous. (Torres Strait Islanders are ethnically and culturally distinct,[90] despite extensive cultural exchange with some of the Aboriginal groups,[91] and the Torres Strait Islands are mostly part of Queensland but have a separate governmental status.) Some Aboriginal people object to being labelled Indigenous, as an artificial and denialist term, because some non-Aboriginal people have referred to themselves as indigenous because they were born in Australia.[84]

Culture and beliefs

[edit]As of 2021, 51% of Indigenous people stated that they held a secular or other spiritual belief or no religious affiliation; 41% were affiliated to Christianity; and 1% were affiliated to a traditional Aboriginal religion.[92]

Australian Indigenous people have beliefs unique to each mob (tribe) and have a strong connection to the land.[93][5] Contemporary Indigenous Australian beliefs are a complex mixture, varying by region and individual across the continent.[7] They are shaped by traditional beliefs, the disruption of colonisation, religions brought to the continent by Europeans, and contemporary issues.[7][8][9] Traditional cultural beliefs are passed down and shared by dancing, stories, songlines and art—especially Papunya Tula (dot painting)—collectively telling the story of creation known as The Dreamtime.[94][93] Additionally, traditional healers were also custodians of important Dreaming stories as well as their medical roles (for example the Ngangkari in the Western desert).[95] Some core structures and themes are shared across the continent with details and additional elements varying between language and cultural groups.[7] For example, in The Dreamtime of most regions, a spirit creates the earth then tells the humans to treat the animals and the earth in a way which is respectful to land. In Northern Territory this is commonly said to be a huge snake or snakes that weaved its way through the earth and sky making the mountains and oceans. But in other places the spirits who created the world are known as wandjina rain and water spirits. Major ancestral spirits include the Rainbow Serpent, Baiame, Dirawong and Bunjil. Similarly, the Arrernte people of central Australia believed that humanity originated from great superhuman ancestors who brought the sun, wind and rain as a result of breaking through the surface of the Earth when waking from their slumber.[76]

Health and economic deprivations

[edit]Taken as a whole, Aboriginal Australians, along with Torres Strait Islander people, have a number of health and economic deprivations in comparison with the wider Australian community.[96][97]

Due to the aforementioned disadvantage, Aboriginal Australian communities experience a higher rate of suicide, as compared to non-indigenous communities. These issues stem from a variety of different causes unique to indigenous communities, such as historical trauma,[98] socioeconomic disadvantage, and decreased access to education and health care.[99] Also, this problem largely affects indigenous youth, as many indigenous youth may feel disconnected from their culture.[100]

To combat the increased suicide rate, many researchers have suggested that the inclusion of more cultural aspects into suicide prevention programs would help to combat mental health issues within the community. Past studies have found that many indigenous leaders and community members, do in fact, want more culturally-aware health care programs.[101] Similarly, culturally-relative programs targeting indigenous youth have actively challenged suicide ideation among younger indigenous populations, with many social and emotional wellbeing programs using cultural information to provide coping mechanisms and improving mental health.[102][103]

Viability of remote communities

[edit]

The outstation movement of the 1970s and 1980s, when Aboriginal people moved to tiny remote settlements on traditional land, brought health benefits,[104][105] but funding them proved expensive, training and employment opportunities were not provided in many cases, and support from governments dwindled in the 2000s, particularly in the era of the Howard government.[106][107][108]

Indigenous communities in remote Australia are often small, isolated towns with basic facilities, on traditionally owned land. These communities have between 20 and 300 inhabitants and are often closed to outsiders for cultural reasons. The long-term viability and resilience of Aboriginal communities in desert areas has been discussed by scholars and policy-makers. A 2007 report by the CSIRO stressed the importance of taking a demand-driven approach to services in desert settlements, and concluded that "if top-down solutions continue to be imposed without appreciating the fundamental drivers of settlement in desert regions, then those solutions will continue to be partial, and ineffective in the long term."[109]

See also

[edit]- Aboriginal Centre for the Performing Arts (ACPA)

- Aboriginal cultures of Western Australia

- Aboriginal South Australians

- Australian Aboriginal culture

- Australian Aboriginal kinship

- Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology

- Climate change in Australia

- First Nations Media Australia

- Indigenous Australian art

- Indigenous Australian music

- Indigenous land rights in Australia

- List of Aboriginal missions in New South Wales

- List of Indigenous Australian firsts

- List of Indigenous Australian politicians

- List of Indigenous Australians in politics and public service

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Lists of Indigenous Australians

- National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Art Award

- Native title in Australia

- Stolen Generations

- Supply Nation

Notes

[edit]- ^ This includes those who identified as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

- ^ The qpGraph analysis confirmed this branching pattern, with the Leang Panninge individual branching off from the Near Oceanian clade after the Denisovan gene flow. The most supported topology indicates around 50% of a basal East Asian component contributing to the Leang Panninge genome (fig. 3c, supplementary figs. 7–11).

- ^ Population change due to overseas migration continued to account for less than 2 per cent of the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander population.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians". Australian Bureau of Statistics. June 2023.

- ^ "2021 Census of Population and Housing, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Profile, Table I01". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ a b Berndt, Ronald M.; Tonkinson, Robert (2023). "Traditional sociocultural patterns". Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Berndt, Ronald M.; Tonkinson, Robert (2023). "Australian Aboriginal peoples". Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ a b Tonkinson, Robert (2011), "Landscape, Transformations, and Immutability in an Aboriginal Australian Culture", Cultural Memories, Knowledge and Space, vol. 4, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 329–345, doi:10.1007/978-90-481-8945-8_18, ISBN 978-90-481-8944-1

- ^ "Community, identity, wellbeing: The report of the Second National Indigenous Languages Survey". AIATSIS. 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d Cox, James Leland (2016). Religion and non-religion among Australian Aboriginal peoples. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4724-4383-0. OCLC 951371681.

- ^ a b Harvey, Arlene; Russell-Mundine, Gabrielle (18 August 2019). "Decolonising the curriculum: using graduate qualities to embed Indigenous knowledges at the academic cultural interface". Teaching in Higher Education. 24 (6): 789–808. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1508131. ISSN 1356-2517. S2CID 149824646.

- ^ a b Fraser, Jenny (25 January 2012). "The digital dreamtime: A shining light in the culture war". Te Kaharoa. 5 (1). doi:10.24135/tekaharoa.v5i1.77. ISSN 1178-6035.

- ^ "2021 Census of Population and Housing, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Profile, Table I01". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ a b Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; Westaway, Michael C.; Muller, Craig; Sousa, Vitor C.; Lao, Oscar; Alves, Isabel; Bergström, Anders; et al. (13 October 2016). "A genomic history of Aboriginal Australia". Nature. 538 (7624): 207–214. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..207M. doi:10.1038/nature18299. hdl:10754/622366. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 7617037. PMID 27654914.

- ^ Graves, Randin (2 June 2017). "Yolngu are People 2: They're not Clip Art". Yidaki History. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ Williams, Martin A. J.; Spooner, Nigel A.; McDonnell, Kathryn; O'Connell, James F. (January 2021). "Identifying disturbance in archaeological sites in tropical northern Australia: Implications for previously proposed 65,000-year continental occupation date". Geoarchaeology. 36 (1): 92–108. Bibcode:2021Gearc..36...92W. doi:10.1002/gea.21822. ISSN 0883-6353. S2CID 225321249. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley; Smith, Mike; Roberts, Richard G.; Hayes, Elspeth; Lowe, Kelsey; Carah, Xavier; Florin, S. Anna; McNeil, Jessica; Cox, Delyth; Arnold, Lee J.; Hua, Quan; Huntley, Jillian; Brand, Helen E. A.; Manne, Tiina; Fairbairn, Andrew; Shulmeister, James; Lyle, Lindsey; Salinas, Makiah; Page, Mara; Connell, Kate; Park, Gayoung; Norman, Kasih; Murphy, Tessa; Pardoe, Colin (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- ^ Veth, Peter; O'Connor, Sue (2013). "The past 50,000 years: an archaeological view". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-1070-1153-3.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (2018). People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory. Taylor & Francis. pp. 250–253. ISBN 978-1-3517-5764-5. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Allen, Jim; O'connell, James F. (2020). "A different paradigm for the initial colonisation of Sahul". Archaeology in Oceania. 55 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1002/arco.5207. ISSN 1834-4453.

Y-chromosome data show parallel patterns, with deeply rooted Sahul-specific haplogroups C and K diverging from the most closely related non-Sahul lineages c.54 ka and dividing into Australia- and New Guinea-specific lineages c.48–53 ka (Bergstrom et al. 2016)." p5 ... While the chronology of Sahul colonisation remains important, we see no arguable cause-and-effect nexus between when Sahul colonisation first occurred and AMH ability to achieve it (cf. Davidson & Noble 1992). If we exclude the extreme age claimed for Madjedbebe (Clarkson et al. 2017) the increasing consensus of available evidence currently puts this event in the range 47–51 ka.

- ^ Tobler, Ray; Rohrlach, Adam; Soubrier, Julien; Bover, Pere; Llamas, Bastien; Tuke, Jonathan; Bean, Nigel; Abdullah-Highfold, Ali; Agius, Shane; O'Donoghue, Amy; O'Loughlin, Isabel; Sutton, Peter; Zilio, Fran; Walshe, Keryn; Williams, Alan N. (8 April 2017). "Aboriginal mitogenomes reveal 50,000 years of regionalism in Australia". Nature. 544 (7649): 180–184. Bibcode:2017Natur.544..180T. doi:10.1038/nature21416. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 28273067.

The timing of human arrival in Australia was estimated using the age of the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) for the different Australian-only haplogroups, calculated using a molecular clock with substitution rates calibrated with ancient European and Asian mitogenomes18. Although these TMRCA values are likely to be minimal estimates given the limited sampling, they group in a narrow window of time from approximately 43–47 ka (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Figs 2, 3), consistent with previous studies (Supplementary Information). ... The resulting independent estimate for initial colonization of Sahul, 48.8 ± 1.3 ka, is a close match to the genetic age estimates (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 4).

- ^ Taufik, Leonard; Teixeira, João C.; Llamas, Bastien; Sudoyo, Herawati; Tobler, Raymond; Purnomo, Gludhug A. (16 December 2022). "Human Genetic Research in Wallacea and Sahul: Recent Findings and Future Prospects". Genes. 13 (12): 2373. doi:10.3390/genes13122373. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 9778601. PMID 36553640.

Genetic inferences suggest that the initial peopling of the region occurred around 50–60 kya, with the separation of Aboriginal Australian and New Guinea populations occurring around the same time [p 6].

- ^ Hublin, Jean-Jacques (9 March 2021). "How old are the oldest Homo sapiens in Far East Asia?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (10) e2101173118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11801173H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2101173118. PMC 7958237. PMID 33602727.

Dating the diversification of present-day lineages of mitochondrial DNA—a part of our genome maternally transmitted—supports a single and rapid dispersal of all ancestral non-African populations less than 55,000 y ago (9).

- ^ Crabtree, Stefani; Williams, Alan N; Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; White, Devin; Saltré, Frédérik; Ulm, Sean (30 April 2021). "We mapped the 'super-highways' the First Australians used to cross the ancient land". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Russell, Lynette; Bird, Michael; Roberts, Richard 'Bert' (5 July 2018). "Fifty years ago, at Lake Mungo, the true scale of Aboriginal Australians' epic story was revealed". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Lourandos, Harry. Continent of Hunter-Gatherers: New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory (Cambridge University Press, 1997) p.81

- ^ Rebe Taylor (2002). Unearthed: The Aboriginal Tasmanians of Kangaroo Island. Kent Town: Wakefield Press. ISBN 978-1-86254-552-6.

- ^ Morse, Dana (30 April 2021). "Researchers demystify the secrets of ancient Aboriginal migration across Australia". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Crabtree, S. A.; White, D. A.; et al. (29 April 2021). "Landscape rules predict optimal superhighways for the first peopling of Sahul". Nature Human Behaviour. 5 (10): 1303–1313. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01106-8. PMID 33927367. S2CID 233458467. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "DNA confirms Aboriginal culture one of Earth's oldest". Australian Geographic. 23 September 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ "Discover the oldest continuous living culture on Earth". The Telegraph. 22 December 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b Bennett, E. Andrew; Liu, Yichen; Fu, Qiaomei (3 December 2024). "Reconstructing the Human Population History of East Asia through Ancient Genomics". Elements in Ancient East Asia. doi:10.1017/9781009246675. ISBN 978-1-009-24667-5.

Australasian, one of three deeply branching East Asian lineages (with AASI and ESEA). AA includes modern-day Papuans and Aboriginal Australians.

- ^ a b Aoki, Kenichi; Takahata, Naoyuki; Oota, Hiroki; Wakano, Joe Yuichiro; Feldman, Marcus W. (30 August 2023). "Infectious diseases may have arrested the southward advance of microblades in Upper Palaeolithic East Asia". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 290 (2005) 20231262. doi:10.1098/rspb.2023.1262. PMC 10465978. PMID 37644833.

A single major migration of modern humans into the continents of Asia and Sahul was strongly supported by earlier studies using mitochondrial DNA, the non-recombining portion of Y chromosomes, and autosomal SNP data [42–45]. Ancestral Ancient South Indians with no West Eurasian relatedness, East Asians, Onge (Andamanese hunter–gatherers) and Papuans all derive in a short evolutionary time from the eastward dispersal of an out-of-Africa population [46,47]

- ^ a b Yang, Melinda A. (6 January 2022). "A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia". Human Population Genetics and Genomics. 2 (1): 1–32. doi:10.47248/hpgg2202010001. ISSN 2770-5005.

Mallick et al. found that a well-fitting admixture graph (qpGraph, Box 1) grouped Papuans, Australians, and the Andamanese Onge with East Asians, with additional Denisovan admixture into Papuans and Australians [15]. ... Though present-day Asians and Australasians are more closely related to each other than to present-day Europeans, genetic comparisons highlight deep separations between mainland East and Southeast Asians, island Southeast Asians, and Australasians.

- ^ a b c d Lipson, Mark; Reich, David (1 April 2017). "A Working Model of the Deep Relationships of Diverse Modern Human Genetic Lineages Outside of Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 34 (4): 889–902. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw293. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 5400393. PMID 28074030.

- ^ Vallini, Leonardo; Zampieri, Carlo; Shoaee, Mohamed Javad; Bortolini, Eugenio; Marciani, Giulia; Aneli, Serena; Pievani, Telmo; Benazzi, Stefano; Barausse, Alberto; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Petraglia, Michael D.; Pagani, Luca (25 March 2024). "The Persian plateau served as hub for Homo sapiens after the main out of Africa dispersal". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 1882. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.1882V. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-46161-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 10963722. PMID 38528002.

- ^ Taufik, Leonard; Teixeira, João C.; Llamas, Bastien; Sudoyo, Herawati; Tobler, Raymond; Purnomo, Gludhug A. (16 December 2022). "Human Genetic Research in Wallacea and Sahul: Recent Findings and Future Prospects". Genes. 13 (12): 2373. doi:10.3390/genes13122373. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 9778601. PMID 36553640.

Genomic data have repeatedly demonstrated that all contemporary non-African AMH populations have diversified from an ancestral AMH group that left Africa between 60–50 kya [28]; however, the initial results from a single deeply sequenced Aboriginal Australian genome derived from a ~100-year-old hair sample proposed that Indigenous Australians also carry substantial AMH ancestry from an earlier African diaspora that originated 75–62 kya [29]. ... though notably a small contribution (~2%) from a deeper AMH source cannot be entirely ruled out [30].

- ^ Hublin, Jean-Jacques (9 March 2021). "How old are the oldest Homo sapiens in Far East Asia?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (10) e2101173118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11801173H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2101173118. PMC 7958237. PMID 33602727.

However, it has often been argued that pioneer groups could have been totally replaced by later demographically dominant waves and thereby, left no genetic trace in extant populations. ... and unless it documents a failed early colonization of Australia, its age is difficult to reconcile with the genetic evidence (9, 12).

- ^ Mallick, Swapan; Li, Heng; Lipson, Mark; Mathieson, Iain; Patterson, Nick; Reich, David (13 October 2016). "The Simons Genome Diversity Project: 300 genomes from 142 diverse populations". Nature. 538 (7624): 201–206. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..201M. doi:10.1038/nature18964. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5161557. PMID 27654912.

- ^ Mondal, Mayukh; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Lao, Oscar (16 January 2019). "Approximate Bayesian computation with deep learning supports a third archaic introgression in Asia and Oceania". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 246. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..246M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08089-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6335398. PMID 30651539.

OOA origin of modern humans, with a Eurasian split between Europeans and the group comprising two subgroups, East Asians, Indian and Andamanese on one hand, and Papuans and Australians on the other.

- ^ a b Huoponen, Kirsi; Schurr, Theodore G.; et al. (1 September 2001). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in an Aboriginal Australian population: evidence for genetic isolation and regional differentiation". Human Immunology. 62 (9): 954–969. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00294-4. PMID 11543898.

- ^ Nagle, Nano; Ballantyne, Kaye N.; van Oven, Mannis; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Xue, Yali; Taylor, Duncan; Wilcox, Stephen; Wilcox, Leah; Turkalov, Rust; van Oorschot, Roland A. H.; McAllister, Peter; Williams, Lesley; Kayser, Manfred; Mitchell, Robert J.; Genographic Consortium (30 March 2016). "Antiquity and diversity of aboriginal Australian Y-chromosomes". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 159 (3): 367–381. Bibcode:2016AJPA..159..367N. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22886. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 26515539.

- ^ Rasmussen, Morten; Guo, Xiaosen; et al. (7 October 2011). "An Aboriginal Australia Genome Reveals Separate Human Dispersals into Asia". Science. 334 (6052). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 94–98. Bibcode:2011Sci...334...94R. doi:10.1126/science.1211177. PMC 3991479. PMID 21940856.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (2011). "First Aboriginal genome sequenced". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.551. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "DNA confirms Aboriginal culture is one of the Earth's oldest". Australian Geographic. 23 September 2011.

- ^ Klein, Christopher (23 September 2016). "DNA Study Finds Aboriginal Australians World's Oldest Civilization". History. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

Updated Aug 22, 2018

- ^ Carlhoff, Selina; Duli, Akin; Nägele, Kathrin; Nur, Muhammad; Skov, Laurits; Sumantri, Iwan; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Hakim, Budianto; Burhan, Basran; Syahdar, Fardi Ali; McGahan, David P. (2021). "Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea". Nature. 596 (7873): 543–547. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 8387238. PMID 34433944.

- ^ Larena, M (March 2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (13) e2026132118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11826132L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512.

- ^ Larena M, McKenna J, Sanchez-Quinto F, Bernhardsson C, Ebeo C, Reyes R, et al. (October 2021). "Philippine Ayta possess the highest level of Denisovan ancestry in the world". Current Biology. 31 (19): 4219–4230.e10. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E4219L. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.07.022. PMC 8596304. PMID 34388371.

- ^ Lipson, Mark; Reich, David (April 2017). "A Working Model of the Deep Relationships of Diverse Modern Human Genetic Lineages Outside of Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 34 (4): 889–902. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw293. PMC 5400393. PMID 28074030.

- ^ a b c Bergström, Anders; Nagle, Nano; Chen, Yuan; McCarthy, Shane; Pollard, Martin O.; Ayub, Qasim; Wilcox, Stephen; Wilcox, Leah; van Oorschot, Roland A. H.; McAllister, Peter; Williams, Lesley; Xue, Yali; Mitchell, R. John; Tyler-Smith, Chris (21 March 2016). "Deep Roots for Aboriginal Australian Y Chromosomes". Current Biology. 26 (6): 809–813. Bibcode:2016CBio...26..809B. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.028. PMC 4819516. PMID 26923783.

- ^ Pugach, Irina; Delfin, Frederick; Gunnarsdóttir, Ellen; Kayser, Manfred; Stoneking, Mark (29 January 2013). "Genome-wide data substantiate Holocene gene flow from India to Australia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (5): 1803–1808. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1803P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211927110. PMC 3562786. PMID 23319617.

- ^ Sanyal, Sanjeev (2016). The ocean of churn: how the Indian Ocean shaped human history. Gurgaon, Haryana, India: Penguin UK. p. 59. ISBN 978-93-86057-61-7. OCLC 990782127.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Anna (15 January 2013). "Research shows ancient Indian migration to Australia". ABC News.

- ^ Bergström, Anders (20 July 2018). Genomic insights into the human population history of Australia and New Guinea (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/CAM.20837.

- ^ Scholander, P. F.; Hammel, H. T.; et al. (1 September 1958). "Cold Adaptation in Australian Aborigines". Journal of Applied Physiology. 13 (2): 211–218. doi:10.1152/jappl.1958.13.2.211. PMID 13575330.

- ^ Caitlyn Gribbin (29 January 2014). "Genetic mutation helps Aboriginal people survive tough climate, research finds" (text and audio). ABC News.

- ^ Qi, Xiaoqiang; Chan, Wee Lee; Read, Randy J.; Zhou, Aiwu; Carrell, Robin W. (22 March 2014). "Temperature-responsive release of thyroxine and its environmental adaptation in Australians". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 281 (1779) 20132747. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2747. PMC 3924073. PMID 24478298.

- ^ a b "Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, Estimated resident population, Indigenous status – 30 June 2021". Australian Bureau of Statistics. June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Understanding change in counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: Census". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4 April 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians". Australian Bureau of Statistics. June 2023.

- ^ Flood, Josephine (2019). The Original Australians. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. p. 217. ISBN 9781760527075.

- ^ Veth, Peter; O'Connor, Sue (2013). "The past 50,000 years: an archaeological view". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 9781107011533.

- ^ Marchese, David (28 March 2018). "Indigenous languages come from just one common ancestor, researchers say". ABC news. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Australian Government, Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications (2020). National Indigenous Languages Report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. p. 13.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "2021 Census of Population and Housing, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Profile, Table I05". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ National Indigenous Language Report (2020). pp. 42, 65

- ^ "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Census". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 28 June 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ National Indigenous Languages Report (2020). p. 46

- ^ "Language Statistics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 25 October 2022.

- ^ National Indigenous Languages Report (2020). pp. 42, 54-55

- ^ Crowley, Field Linguistics, 2007:3

- ^ Claire Bowern, September 2012, "The riddle of Tasmanian languages", Proc. R. Soc. B, 279, 4590–4595, doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1842

- ^ NJB Plomley, 1976b. Friendly mission: the Tasmanian journals of George Augustus Robinson 1829–34. Kingsgrove. pp. xiv–xv.

- ^ "T16: Palawa kani". 26 July 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Fiona (19 June 2021). "Aboriginal sign languages have been used for thousands of years". ABC News online. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ a b Lourandos, Harry. New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom (1997) ISBN 0-521-35946-5

- ^ Horton, David (1994) The Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History, Society, and Culture, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra. ISBN 0-85575-234-3.

- ^ a b Read, Peter; Broome, Richard (1982). "Aboriginal Australians". Labour History (43): 125–126. doi:10.2307/27508560. ISSN 0023-6942. JSTOR 27508560.

- ^ Garde, Murray. "bininj". Bininj Kunwok Dictionary. Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "General Reference". Life and Times of the Gunggari People, QLD (Pathfinder). Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Monaghan, Paul (2017). "Chapter 1: Structures of Aboriginal life at the time of colonisation". In Brock, Peggy; Gara, Tom (eds.). Colonialism and its Aftermath: A history of Aboriginal South Australia. Wakefield Press. pp. 10, 12. ISBN 978-1-74305-499-4. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; et al. (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- ^ Walsh, Michael; Yallop, Colin (1993). Language and Culture in Aboriginal Australia. Aboriginal Studies Press. pp. 191–193. ISBN 978-0-85575-241-5.

- ^ Edwards, W. H. (2004). An Introduction to Aboriginal Societies (2nd ed.). Social Science Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-876633-89-9.

- ^ a b Fesl, Eve D. (1986). "'Aborigine' and 'Aboriginal'". Aboriginal Law Bulletin. (1986) 1(20) Aboriginal Law Bulletin 10 Accessed 19 August 2011

- ^ a b "Don't call me indigenous: Lowitja". The Age. Melbourne. Australian Associated Press. 1 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Solonec, Tammy (9 August 2015). "Why saying 'Aborigine' isn't OK: 8 facts about Indigenous people in Australia". Amnesty.org. Amnesty International. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "Why do media organisations like News Corp, Reuters and The New York Times still use words like 'Aborigines'?". NITV. 5 March 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "Aboriginality and Identity: Perspectives, Practices and Policies" (PDF). New South Wales AECG Inc. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Blandy, Sarah; Sibley, David (2010). "Law, boundaries and the production of space". Social & Legal Studies. 19 (3): 275–284. doi:10.1177/0964663910372178. S2CID 145479418. "Aboriginal Australians are a legally defined group" (p. 280).

- ^ Malbon, Justin (2003). "The Extinguishment of Native Title—The Australian Aborigines as Slaves and Citizens". Griffith Law Review. 12 (2): 310–335. doi:10.1080/10383441.2003.10854523. S2CID 147150152. Aboriginal Australians have been "assigned a separate legally defined status" (p 322).

- ^ "About the Torres Strait". Torres Strait Shire Council. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Australia Now – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples". 8 October 2006. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ "2021 Census of Population and Housing, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Profile, Table I01". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ a b "Behind the dots of Aboriginal Art". Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Green, Jennifer (2012). "The Altyerre Story-'Suffering Badly by Translation': The Altyerre Story". The Australian Journal of Anthropology. 23 (2): 158–178. doi:10.1111/j.1757-6547.2012.00179.x.

- ^ Traditional healers of central Australia: Ngangkari. Broome, Western Australia: Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjar Yankunytjatjara Women's Council Aboriginal Corporation, Magabala Books Aboriginal Corporation. 2013. ISBN 978-1-921248-82-5. OCLC 819819283.

- ^ "4704.0 - The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Oct 2010". Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Government. 17 February 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ "Indigenous Socioeconomics Indicators, Benefits and Expenditure". Parliament of Australia. 7 August 2001. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Elliott-Farrelly, Terri (January 2004). "Australian Aboriginal suicide: The need for an Aboriginal suicidology?". Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health. 3 (3): 138–145. doi:10.5172/jamh.3.3.138. ISSN 1446-7984. S2CID 71578621.

- ^ Marrone, Sonia (July 2007). "Understanding barriers to health care: a review of disparities in health care services among indigenous populations". International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 66 (3): 188–198. doi:10.3402/ijch.v66i3.18254. ISSN 2242-3982. PMID 17655060. S2CID 1720215.

- ^ Isaacs, Anton; Sutton, Keith (16 June 2016). "An Aboriginal youth suicide prevention project in rural Victoria". Advances in Mental Health. 14 (2): 118–125. doi:10.1080/18387357.2016.1198232. ISSN 1838-7357. S2CID 77905930.

- ^ Ridani, Rebecca; Shand, Fiona L.; Christensen, Helen; McKay, Kathryn; Tighe, Joe; Burns, Jane; Hunter, Ernest (16 September 2014). "Suicide Prevention in Australian Aboriginal Communities: A Review of Past and Present Programs". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 45 (1): 111–140. doi:10.1111/sltb.12121. ISSN 0363-0234. PMID 25227155.

- ^ Skerrett, Delaney Michael; Gibson, Mandy; Darwin, Leilani; Lewis, Suzie; Rallah, Rahm; De Leo, Diego (30 March 2017). "Closing the Gap in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth Suicide: A Social-Emotional Wellbeing Service Innovation Project". Australian Psychologist. 53 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1111/ap.12277. ISSN 0005-0067. S2CID 151609217.

- ^ Murrup-Stewart, Cammi; Searle, Amy K.; Jobson, Laura; Adams, Karen (16 November 2018). "Aboriginal perceptions of social and emotional wellbeing programs: A systematic review of literature assessing social and emotional wellbeing programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians perspectives". Australian Psychologist. 54 (3): 171–186. doi:10.1111/ap.12367. ISSN 0005-0067. S2CID 150362243.

- ^ Morice, Rodney D. (1976). "Woman Dancing Dreaming: Psychosocial Benefits of the Aboriginal Outstation Movement". Medical Journal of Australia. 2 (25–26). AMPCo: 939–942. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1976.tb115531.x. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 1035404. S2CID 28327004.

- ^ Ganesharajah, Cynthia (April 2009). Indigenous Health and Wellbeing: The Importance of Country (PDF). Native Title Research Report Report No. 1/2009. AIATSIS. Native Title Research Unit. ISBN 978-0-85575-669-7. Retrieved 17 August 2020. AIATSIS summary Archived 4 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Myers, Fred; Peterson, Nicolas (January 2016). "1. The origins and history of outstations as Aboriginal life projects". In Peterson, Nicolas; Myers, Fred (eds.). Experiments in self-determination: Histories of the outstation movement in Australia. Monographs in Anthropology. ANU Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-925022-90-2. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Palmer, Kingsley (January 2016). "10. Homelands as outstations of public policy". In Peterson, Nicolas; Myers, Fred (eds.). Experiments in self-determination: Histories of the outstation movement in Australia. Monographs in Anthropology. ANU Press. ISBN 978-1-925022-90-2. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Altman, Jon (25 May 2009). "No movement on the outstations". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Smith, M. S.; Moran, M.; Seemann, K. (2008). "The 'viability' and resilience of communities and settlements in desert Australia". The Rangeland Journal. 30 (1): 123. Bibcode:2008RangJ..30..123S. doi:10.1071/RJ07048.

![]() This article incorporates text by Anders Bergström et al. available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Anders Bergström et al. available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

Further reading

[edit]- "Start exploring Australian Aboriginal culture". Creative Spirits. 24 December 2018.

- "Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies". AIATSIS.

- "Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies". AIATSIS.

- "Aboriginal Art of Australia: Understanding its History". ARTARK. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

External links

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

Media related to Aboriginal Australians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aboriginal Australians at Wikimedia Commons

Aboriginal Australians

View on GrokipediaAboriginal Australians are the indigenous peoples of mainland Australia and Tasmania, descendants of one of the earliest successful migrations of anatomically modern humans out of Africa, arriving on the continent around 65,000 years ago via land bridges and short sea crossings during lowered sea levels.[1][2] Genomic studies reveal they form a deeply structured genetic lineage basal to many East Eurasian populations, with limited later admixture except for up to 11% Indian-related ancestry in northern groups from ~4,000 years ago, reflecting distinct evolutionary isolation and adaptation to Australia's diverse ecosystems.[3][4] Pre-contact populations are estimated to have numbered in the hundreds of thousands to possibly over a million, organized into hundreds of distinct tribal groups speaking more than 250 languages and dialects, sustaining complex hunter-gatherer societies without agriculture through intimate knowledge of fire-stick farming, seasonal resource cycles, and oral traditions encoding environmental and social laws.[5][6] European colonization from 1788 led to massive demographic collapse from introduced diseases, violence, and dispossession, reducing numbers to tens of thousands by the early 20th century, though cultural resilience persists amid ongoing debates over land rights, health disparities, and recognition of pre-colonial achievements like continent-wide ecological management.[7] Today, approximately 900,000 people identify as Aboriginal Australians, comprising about 3.2% of the national population, with genetic continuity affirmed but cultural practices varying widely due to historical disruptions and modern integrations.[8]

Origins and Prehistory

Genetic and Archaeological Evidence

Archaeological evidence indicates that Aboriginal Australians represent one of the earliest successful dispersals of anatomically modern humans beyond Africa, with the oldest securely dated site at Madjedbebe rock shelter in Arnhem Land, northern Australia, yielding occupation layers dated to approximately 65,000 years ago through optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) on single grains of quartz.[9] This site contains ground-edge stone axes, edge-ground axe fragments, and evidence of ochre processing and plant grinding, artifacts more advanced than those from contemporaneous Eurasian sites, suggesting rapid technological adaptation upon arrival.[9] Earlier estimates placed initial settlement around 40,000–50,000 years ago based on radiocarbon dating, but revised OSL methods have pushed the timeline back, though some researchers question the 65,000-year date due to potential sediment mixing or post-depositional disturbance.[10] Other Pleistocene sites across Sahul—the Pleistocene landmass comprising Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania—corroborate widespread early occupation, including Widgingarri 1 in the Kimberley region with dates exceeding 50,000 years and evidence of coastal resource use preserved by geological uplift.[11] Devil's Lair in southwest Australia provides dates around 48,000 years ago, while sites like Puritjarra rock shelter in central Australia show continuous occupation from at least 35,000 years ago through the Last Glacial Maximum, demonstrating resilience to arid conditions.[12] Submerged landscapes on the Northwest Shelf, now underwater due to post-glacial sea-level rise around 12,000–7,000 years ago, likely hosted significant populations, with modeling estimating up to 500,000 people in refugia during low sea stands.[13] These findings refute later-arrival hypotheses and align with a single founding migration via island-hopping across Wallacea. Genetic studies confirm deep ancestry divergence, with Aboriginal Australian genomes clustering basal to other Eurasians and sharing a common origin with Papuans from an early out-of-Africa wave around 51,000–72,000 years ago, followed by isolation with minimal gene flow until European contact.[1] Key evidence includes a 2016 Nature study analyzing Aboriginal and Papuan genomes, confirming early divergence from Out-of-Africa migrants 50,000–70,000 years ago, and a 2011 genome sequenced from historical Aboriginal hair indicating descent from migrants up to 75,000 years ago.[3][14] Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups such as S, M42, and P dominate, tracing to founder events with coalescent ages exceeding 50,000 years, while Y-chromosome haplogroup C-M130 variants exhibit antiquity and low diversity indicative of small founding populations; these support arrival in Sahul around 50,000–65,000 years ago from the same Out-of-Africa population.[15][16] Aboriginal Australians carry 3–5% Denisovan admixture, higher than in mainland Eurasians but less than in some Papuans, likely acquired en route through Southeast Asia, alongside Neanderthal introgression; this archaic DNA includes adaptive variants for immunity and metabolism suited to island environments.[1][17] Whole-genome analyses reveal no substantial Holocene admixture from South Asia despite isolated Y-chromosome signals, underscoring genetic continuity despite cultural exchanges.[18] Principal component analysis positions Aboriginal samples distinct from East Asians, nearest to Oceanian groups, reflecting geographic isolation post-Sahul formation around 65,000–50,000 years ago.[19]

Settlement and Migration Patterns

Archaeological evidence, including stone tools and ochre from sites like Madjedbebe rock shelter in northern Australia, indicates human occupation as early as 65,000 years ago, suggesting initial settlement during a period of lower sea levels that connected Southeast Asia to Sahul (the combined landmass of Australia and New Guinea).[20] However, ancient DNA analyses conflict with these dates, estimating divergence from Asian populations and arrival around 50,000 years ago, implying that older archaeological layers may reflect natural deposition rather than human activity or that genetic models better account for isolation and drift in small founding populations.[21][22] This discrepancy highlights tensions between material evidence and genomic clocks calibrated against out-of-Africa migrations, with genetics privileging a single major wave from Southeast Asia rather than multiple early pulses.[23] Migration likely occurred via short sea crossings from island Southeast Asia (Wallacea), requiring watercraft capable of navigating 50-100 km gaps, as no continuous land bridge existed even at glacial maxima; northern routes through Sulawesi and West Papua or southern paths via Timor are both plausible, with recent cave finds in Timor supporting rapid coastal dispersal around 44,000 years ago.[10][24][25] Maternal lineages (mtDNA) trace a swift expansion southward and eastward from northern entry points, diverging from Papuan ancestors by 25,000-37,000 years ago despite ongoing land connections until sea levels rose ~10,000 years ago, indicating behavioral or ecological separation prior to physical isolation.[26][27] Populations spread rapidly across diverse biomes, reaching southeastern Australia and Tasmania by ~40,000 years ago—before the latter's isolation via Bass Strait flooding—with evidence of adaptation to arid interiors and coastal zones within millennia of arrival, forming territorially distinct groups by 30,000-40,000 years ago.[22][10] A later gene flow event ~4,000 years ago, introducing dingo ancestry and possibly bow-and-arrow technology from Indian Ocean contacts, overlaid this foundational pattern without displacing core lineages.[28] These dynamics reflect causal drivers like climate-driven resource patches and low population densities enabling unchecked range expansion, rather than coordinated mass movements.Environmental Adaptations and Cultural Developments

Upon arriving in Sahul approximately 65,000 years ago, Aboriginal Australians encountered a continent with diverse and often harsh environments, including arid interiors and variable climates, necessitating rapid adaptations in subsistence and mobility. Archaeological evidence from sites like Madjedbebe reveals early use of grinding stones for processing seeds, dating back 65,000 years, indicating exploitation of plant resources in fluctuating conditions.[29] These adaptations involved seasonal movements to track water and food sources, with groups maintaining intimate knowledge of over 100 plant species and ephemeral water points in arid zones.[30] A key environmental management practice was fire-stick farming, involving frequent low-intensity burns to create mosaics of vegetation that enhanced biodiversity, facilitated hunting by attracting game to regrowth, and reduced fuel for wildfires. Sediment core analysis from western Victoria demonstrates this practice persisted at least from 11,000 years ago, shaping floral and faunal distributions across the continent.[31] Quantitative studies confirm that such anthropogenic fires increased grassland extent and prey availability, supporting population densities without domesticated agriculture.[32] In arid regions, fires also aided in locating water by exposing soakages and promoting fire-adapted species.[33] Technological innovations included the development of edge-ground stone axes, with fragments from Nawarla Gabarnmang dated to 49,000–44,000 years ago, among the earliest globally, used for woodworking, tool hafting, and resource processing suited to Australia's timber-scarce landscapes.[34] Boomerangs and spears optimized hunting efficiency, while seed-grinding techniques produced nutrient-dense flours, evidencing multi-purpose microlithic tools by 30,000 years ago.[35] Water management entailed constructing wells, dams, and using spinifex resin for sealing containers, with ethnographic and archaeological records showing sophisticated locating of subterranean sources via behavioral cues of animals and plants.[36] Cultural developments intertwined with these adaptations through songlines, oral narratives encoding navigational, ecological, and resource knowledge across vast distances, corroborated by alignments with submerged paleolandscapes off northwest Australia.[37] This system facilitated intergenerational transmission of survival strategies, including ritual continuity evidenced at sites like Cloggs Cave, where ochre processing for ceremonies dates continuously from 30,000 years ago to recent times.[38] Such knowledge systems emphasized empirical observation of environmental cues, enabling sustained hunter-gatherer economies without permanent settlements or intensive agriculture, aligned with the continent's unpredictable hydrology and soils.[39]Traditional Society and Culture

Social Organization and Kinship Systems

Aboriginal Australian societies were organized into small, nomadic bands or local descent groups typically comprising 20 to 50 individuals, with membership fluid based on kinship ties, resource availability, and seasonal movements across defined territories linked to totemic affiliations.[40] These bands lacked centralized political authority or hereditary chiefs; instead, decision-making occurred through consensus among senior elders, who held influence derived from knowledge, age, and demonstrated wisdom rather than coercion.[41] Leadership roles were often gender-specific, with men directing hunting and ritual matters and women managing gathering and child-rearing, though both participated in communal governance.[40] Kinship systems formed the core of social structure, employing classificatory terminology that grouped relatives into broad categories beyond biological ties, thereby extending obligations of reciprocity, avoidance, and alliance across bands.[42] These systems integrated matrilineal or patrilineal descent with totemic identities, where individuals inherited spiritual connections to specific animals, plants, or landscapes that prescribed behaviors and reinforced territorial claims.[43] Marriage rules emphasized exogamy to prevent incest and foster intergroup ties, prohibiting unions within the same moiety or section while mandating specific compatible categories.[44] Many groups divided society into moieties—two complementary halves such as "sun side" and "shade side"—which determined primary marriage partners and ritual divisions, with descent patrilineal in some regions like central Australia.[43] More complex arrangements featured sections (four groups) or subsections (eight "skin names"), unique to Aboriginal Australia, where each category prescribed not only spouses but also roles in ceremonies and prohibitions like mother-in-law avoidance to maintain social harmony.[42] For instance, in subsection systems prevalent in northern Australia, an individual from one skin name marries only from prescribed others, with children inheriting the father's skin, ensuring cyclical alliances.[44] These categories extended beyond kinship to regulate all social interactions, embedding causal links between genealogy, land tenure, and cultural continuity.[40]Economy, Technology, and Subsistence Practices

Aboriginal Australians maintained a hunter-gatherer economy prior to European contact, relying on foraging, hunting, and fishing for subsistence without domesticated crops or livestock, except for the introduced dingo around 4,000 years ago.[45] This system supported populations estimated at 300,000 to 1 million across the continent, with practices adapted to diverse environments from arid interiors to coastal regions.[46] Men typically hunted large game using spears and boomerangs, while women gathered seeds, roots, fruits, and small animals, often providing the majority of caloric intake through plant foods.[45] Regional variations included intensive fishing with weirs and nets in riverine areas and shellfish harvesting along coasts.[47] Technological adaptations emphasized portability and multi-functionality, featuring hafted stone tools such as microliths for spear tips, knives, and scrapers, hafted with plant resins.[48] Wooden implements included spears (up to 3 meters long), boomerangs for hunting and warfare, and the woomera spear-thrower to extend throwing range and force.[49] Grinding stones processed seeds into flour, while digging sticks and nets facilitated gathering; bark canoes enabled fishing in northern and eastern waters.[35] Absent were metallurgy, pottery, or the bow and arrow, with stone flaking techniques persisting for over 65,000 years.[50] Land management through fire-stick farming shaped ecosystems, with frequent low-intensity burns creating mosaic landscapes that promoted regrowth of grasses to attract herbivores and reduce wildfire risks, evidenced by charcoal records dating to at least 11,000 years ago in northern Australia.[31] Quantitative studies confirm this practice enhanced foraging efficiency by increasing plant and animal patchiness rather than depleting resources.[32] Subsistence emphasized seasonal mobility, with groups following resource cycles in territories defined by kinship and lore. Economic exchanges occurred via extensive trade networks along Dreaming paths, distributing materials like red ochre from northern mines to southeastern coasts over 1,500 kilometers, alongside tools, shells, and cultural knowledge, without formalized currency but through reciprocity and ceremonial gifting.[51] These systems mitigated local shortages and fostered intergroup alliances, integrating economic with spiritual dimensions.[52] Overall, the economy prioritized sustainability and social obligations over accumulation, yielding nutritional self-sufficiency in pre-contact conditions.[53]Spiritual Beliefs, Rituals, and Mythology