Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bandage

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

A bandage is a piece of material used either to support a medical device such as a dressing or splint, or on its own to provide support for the movement of a part of the body. When used with a dressing, the dressing is applied directly on a wound, and a bandage is used to hold the dressing in place. Other bandages are used without dressings, such as elastic bandages, which are used to reduce swellings or to provide support to a sprained joint. Tight bandages can be used to slow blood flow to an extremity, such as when a leg or arm is bleeding heavily.

Bandages are available in a wide range of types, from generic cloth strips to specially shaped bandages designed for a specific limb or part of the body. Bandages can often be improvised as the situation demands, using clothing, blankets or other material. In American English, the word bandage is often used to indicate a small gauze dressing attached to an adhesive bandage.

Types

[edit]Gauze bandage

[edit]

The most common type of bandage is the gauze bandage, a woven strip of material. A gauze bandage can come in any number of widths and lengths and can be used for almost any bandage application, including holding a dressing in place.

Adhesive bandage

[edit]Liquid bandage

[edit]Compression bandage

[edit]

The term "compression bandage" refers to a wide variety of bandages with many different applications:

- Short stretch compression bandages are applied to a limb (usually for treatment of lymphedema or venous ulcers).[citation needed] This type of bandage is capable of shortening around the limb after application and is therefore not exerting ever-increasing pressure during inactivity. This dynamic is called resting pressure and is considered safe and comfortable for long-term treatment. Conversely, the stability of the bandage creates a very high resistance to stretch when pressure is applied through internal muscle contraction and joint movement. This force is called working pressure.

- Long stretch compression bandages have long stretch properties, meaning that their high compressive power can be easily adjusted. However, they also have a very high resting pressure and must be removed at night or if the patient is in a resting position.

Triangular bandage

[edit]Also known as a cravat bandage, a triangular bandage is a piece of cloth put into a right-angled triangle, and often provided with safety pins to secure it in place. It can be used fully unrolled as a sling, folded as a normal bandage, or for specialized applications, such as on the head. One advantage of this type of bandage is that it can be makeshift and made from a fabric scrap or a piece of clothing. The Scouting movement popularized the use of this bandage in many of their first aid lessons, as a part of the uniform is a neckerchief which can easily be folded to form a cravat.

Tube bandage

[edit]A tube bandage is applied using an applicator, and is woven in a continuous circle. It is used to hold dressings or splints on to limbs, or to provide support to sprains and strains, so that it stops bleeding.

Kirigami bandage

[edit]A new type of bandage was invented in 2016; inspired by the art of kirigami, it uses parallel slits to better fit areas of the body that bend. The bandages have been produced with 3D-printed molds.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Paper-folding art inspires better bandages". MIT News Office. 27 March 2018.

External links

[edit]- "Use of Paper Dressings for Wounds", Popular Science, February 1919, page 68, scanned by Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=7igDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA68

- "A Mechanical Helper for the Red Cross, Popular Science, February 1919, page 74, scanned by Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=7igDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA74

Bandage

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Etymology

A bandage is a piece of material used to support a wound, injury, or body part, typically consisting of cloth, plastic, or other flexible substances applied to secure a dressing, provide compression, or immobilize an area.[12] Unlike a wound dressing, which is placed directly in contact with the injury to absorb fluids, protect against infection, and promote healing, a bandage serves primarily as an external layer to hold the dressing in place or offer structural support without direct wound contact.[13][14] The term "bandage" originates from the Middle French word bandage, denoting a strip of cloth, which entered English in the late 16th century to describe material for binding wounds.[4] It derives from the Old French bende or bande, meaning a band or strip, ultimately tracing back to a Frankish root related to binding or tying, with the verb form bander signifying "to bind."[12] The word's first documented medical application appears in 16th-century texts, reflecting its evolution from general binding tools to specialized wound care items.[4] Related terms include "plaster," which in British English refers to an adhesive bandage—a subset of bandages featuring a sticky backing for direct minor wound coverage—while a tourniquet differs as a device designed specifically to constrict blood flow in cases of severe arterial bleeding, rather than providing general support or protection.[15][16]Primary Functions

Bandages serve several core functions in medical care, primarily aimed at supporting the healing process and managing injury-related complications. One of the foremost roles is protection, where bandages act as a physical barrier to shield wounds from external contaminants such as dirt, bacteria, and mechanical trauma, thereby reducing the risk of infection and promoting an optimal environment for tissue repair.[5] This protective function is essential for both minor cuts and more significant injuries, as it helps maintain wound integrity during the initial healing stages.[17] Another critical function is compression, which involves applying controlled pressure to the injured area to minimize swelling, staunch bleeding, and enhance circulation, particularly in cases of sprains, strains, or venous ulcers. Elastic or specialized compression bandages achieve this by constricting blood vessels and facilitating venous return, which can significantly accelerate recovery when applied correctly.[18] For instance, in soft tissue injuries, compression reduces edema formation and supports the underlying structures without impeding overall blood flow.[19] Immobilization is a key function for bandages in stabilizing injured limbs, joints, or fractures, preventing further displacement or movement that could exacerbate damage and delay healing. By securing the affected area, bandages limit motion, reduce pain, and allow natural recovery processes to occur undisturbed, often in conjunction with splints for more severe cases.[18] Bandages also facilitate absorption by holding absorbent dressings in place to soak up exudate, blood, or other fluids from wounds, which prevents maceration of surrounding skin and maintains a clean wound bed conducive to healing.[17] This function is particularly vital for moderate to heavily draining injuries, where unchecked moisture could otherwise lead to infection or prolonged inflammation.[20]Historical Development

Ancient and Pre-Modern Uses

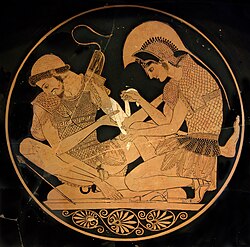

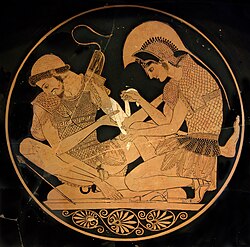

In ancient Egypt around 3000 BCE, bandages were primarily constructed from linen strips, which were soaked in resin or honey to treat wounds and immobilize injuries, a practice documented in early medical texts and evidenced by mummification techniques. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, dating to approximately 1600 BCE, describes the use of these linen wrappings for fracture management, such as splinting broken bones with padded wood or bark, where the bandages were stiffened by mixtures of honey, resins, and powdered grains to promote adhesion and provide a protective barrier. Honey served as a natural antiseptic, while resins added durability, reflecting an early understanding of wound closure and infection prevention through natural substances.[21] During the Greek and Roman eras, bandaging techniques advanced with contributions from physicians like Hippocrates around 400 BCE, who detailed methods for securing fractures using layered linen bandages reinforced with wax-based ointments, changed periodically to monitor swelling and ensure proper alignment. In the 2nd century CE, Galen of Pergamon expanded on these practices, employing wool for its absorbent and hemostatic properties in dressings and silk threads for ligatures to control bleeding during surgical interventions, marking a shift toward more specialized materials for wound stabilization and closure. These approaches emphasized immobilization and protection but were limited by the absence of systematic sterilization.[22] In medieval Europe and Asia, Islamic medicine, as outlined in Avicenna's Canon of Medicine from the 11th century, incorporated herbal-infused cloth bindings for wound care, utilizing bandages with two heads for secure application and integrating natural agents like boswellia and plantain to reduce inflammation and support healing. Concurrently, traditional Chinese practices employed silk fabrics for flexible wrappings and bamboo splints for rigid support in treating injuries, often combined with herbal poultices to aid recovery, as seen in historical trauma case records. These methods relied heavily on natural fibers such as linen, wool, silk, and bamboo, which, while readily available, lacked sterilization processes, frequently resulting in infections due to contamination from unprocessed materials and environmental exposure.[23][24][8]Modern Innovations

In the 19th century, advancements in rubber processing enabled the development of elastic bandages for compression therapy, with vulcanization of rubber in 1839 by Charles Goodyear providing a durable, stretchable material that improved wound support and circulation management.[25] This innovation marked a shift from rigid linen wrappings to flexible options that could conform to body contours without restricting movement. Concurrently, the standardization of first aid protocols began post-1860s through the International Red Cross, founded in 1863 following the Geneva Convention, which established uniform guidelines for battlefield dressings and training to ensure consistent wound care across nations.[26] The early 20th century saw pivotal inventions in adhesive technology, exemplified by Earle Dickson's creation of the first ready-made adhesive bandage in 1920 while employed at Johnson & Johnson; this prototype, refined and patented as the Band-Aid in 1921, combined sterile gauze with adhesive tape for convenient minor wound coverage.[27] World War I accelerated mass production of gauze bandages to meet wartime demands, with companies like Johnson & Johnson scaling up manufacturing to supply millions of sterile dressings, reducing infection rates among soldiers through accessible, hygienic materials.[28] By World War II, triangular bandages evolved as essential field tools, with military adaptations emphasizing compact, multifunctional designs for slings, compresses, and limb stabilization, as refined in British and Allied protocols for rapid deployment.[29] The late 20th century introduced tubular bandages in the 1960s, pioneered by innovations like Tubigrip in 1958 by Medlock Medical, which offered seamless, elastic netting for secure limb application without clips or tape, simplifying retention of dressings on irregular shapes.[30] Liquid bandages emerged in the 1970s based on cyanoacrylate adhesives, such as n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, providing a polymerizing film that sealed superficial cuts with minimal tissue toxicity and rapid bonding for outpatient use.[31] Entering the 21st century, antimicrobial coatings transformed bandages, with silver nanoparticle integrations gaining prominence in the 2000s; for instance, Acticoat dressings, launched around 2000, utilized nanocrystalline silver to release ions that inhibit bacterial growth, significantly lowering infection risks in chronic wounds.[32] More recently, prototypes of smart bandages incorporating sensors for real-time monitoring of moisture, pH, and infection markers have advanced into clinical testing by the 2020s, such as the USC-developed e-textile systems that wirelessly transmit data to guide targeted interventions and accelerate healing.[33]Materials and Composition

Fabrics and Textiles

Cotton gauze serves as one of the most common fabric materials in bandages due to its high absorbency and breathability, allowing it to effectively manage wound exudate while permitting air circulation to promote healing.[34] Typically woven or non-woven from 100% cotton yarns, it exhibits low adherence to wounds, making it suitable for packing and dressing applications without disrupting tissue during removal.[35] Its soft texture minimizes irritation, particularly in sensitive areas.[36] Elastic fabrics, often incorporating spandex or latex blends with cotton or synthetics, provide essential stretch properties for bandages requiring compression and conformability.[37] These materials can achieve up to 200% elongation, enabling secure application over contoured body parts while maintaining consistent pressure to support circulation and reduce swelling.[38] The elasticity ensures durability during repeated use without permanent deformation.[39] Synthetic textiles such as polyester and nylon offer advantages in durability and hypoallergenicity, making them ideal for environments demanding repeated sterilization and minimal skin reactions.[40] Polyester, in particular, provides strength and resistance to abrasion, while nylon contributes elasticity and quick-drying properties, often rendering these fabrics non-absorbent to maintain a clean, dry barrier.[41] Their inert nature reduces the risk of allergic responses compared to some natural fibers.[42] Among natural alternatives, silk is valued for its biocompatibility and suitability for sensitive skin, exhibiting anti-inflammatory properties that aid in wound healing without causing irritation.[35] Linen, derived from flax, provides rigid support in both historical and modern contexts due to its strength and breathability, though it is less flexible than other options.[43] These materials are selected for applications where gentleness or structural integrity is paramount. Weave types significantly influence bandage performance; plain weaves, common in gauze, enhance flexibility and conformability for easy application over irregular surfaces.[44] Tubular weaves create seamless, cylindrical structures that facilitate uniform pressure distribution and simplify securing dressings without edges that could cause discomfort.[45] Some elastic fabrics may integrate adhesives for enhanced adhesion, though the weave primarily determines the base structure.Adhesives, Liquids, and Coatings

Adhesives in bandages primarily consist of pressure-sensitive formulations designed to secure the dressing to the skin without causing excessive trauma upon removal. Common types include acrylic-based adhesives, which provide strong and long-lasting adhesion suitable for extended wear, and rubber-based adhesives, offering high initial tack for quick application on various skin types. [47] [48] Hypoallergenic variants, such as silicone-based adhesives, are formulated to minimize skin irritation and are particularly gentle, exhibiting lower peel adhesion forces that reduce pain and tissue damage during removal. [47] [49] Liquid bandages, also known as tissue adhesives, utilize cyanoacrylate polymers, such as 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, which rapidly polymerize upon contact with moisture from the skin or wound to form a strong, flexible, and waterproof seal that approximates wound edges and protects against microbial invasion. [50] This polymerization process typically achieves initial drying and sufficient strength within 30 to 60 seconds, allowing for immediate use without traditional wrapping, though full curing may take slightly longer for thicker applications. [51] Coatings applied to bandage surfaces enhance protective and therapeutic properties beyond basic adhesion. Antimicrobial agents, such as silver ions, are incorporated into these coatings to provide broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against common wound pathogens, including MRSA, by releasing ions that disrupt bacterial cell functions over several days. [52] Waterproof silicone coatings, often vapor-permeable, offer moisture resistance while allowing excess exudate to pass through, maintaining a balanced wound environment and preventing maceration. [53] Iodine-based coatings, like those using povidone-iodine, serve as antiseptics to reduce infection risk in minor wounds, though they are less common in modern dressings due to potential staining and sensitization. [31] Hypoallergenic considerations are integral to adhesive and coating design, with many products formulated as latex-free to mitigate allergy risks; natural rubber latex sensitivity affects approximately 1% to 6% of the general population, manifesting as contact dermatitis or more severe reactions upon exposure. [54] Silicone and synthetic alternatives address these concerns by avoiding latex proteins while maintaining efficacy. [55] In response to environmental concerns, biodegradable adhesives have emerged in eco-friendly bandage designs since the 2010s, utilizing polymers like polyesters or hydrogels derived from natural sources such as chitosan and hyaluronic acid, which degrade harmlessly in the body or environment without leaving residues. [56] [57] These developments prioritize sustainability while ensuring biocompatibility and adhesion performance comparable to traditional materials. [58]Types of Bandages

Roller and Gauze Bandages

Roller and gauze bandages consist of a continuous roll made from absorbent gauze, typically a plain-woven cloth composed of cotton or a blend of cotton and up to 53 percent rayon by weight.[59] These bandages are available in widths ranging from 2 to 6 inches and lengths of 4 to 10 yards, often supplied in sterile, individually wrapped packaging to maintain hygiene during medical use.[60] They serve primarily to secure primary wound dressings in place, provide light compression to minimize swelling, and support injured areas such as limbs or joints through wrapping techniques like the figure-eight pattern, which allows for secure coverage around angular body parts.[61] Key advantages include their ability to conform flexibly to body contours, ensuring even coverage without bunching, and their low cost, approximately $0.10 to $0.20 per yard in bulk non-sterile forms, making them accessible for widespread clinical and first-aid applications.[62][63] Conforming variants incorporate stretchy materials like rayon or polyester knits, enhancing adaptability to movement while maintaining breathability.[64] Standardization is governed by United States Pharmacopeia (USP) requirements for absorbent gauze, including a minimum absorbency of eight times the material's weight in water to ensure effective fluid management without degradation.[65] Limitations include the potential for slippage on curved or mobile areas if not anchored with tape or clips, as they lack self-adherent properties, which can compromise coverage during activity.[66]Adhesive Bandages

Adhesive bandages, also known as sticking plasters or Band-Aids, are self-adhesive patches specifically designed for covering and protecting minor cuts, scrapes, and abrasions on the skin. They consist of a central absorbent pad, typically made of gauze or foam, attached to a strip of adhesive-backed fabric or plastic that adheres directly to the surrounding skin, providing a barrier against dirt and bacteria while allowing the wound to breathe. The standard size for these bandages is 1 inch by 3 inches, though they are available in various dimensions to suit different wound sizes and body locations. Butterfly bandages, also known as Steri-Strips, are a variant of adhesive bandages designed as narrow strips to approximate the edges of minor lacerations without the need for stitches.[67][68][1] The invention of the adhesive bandage is credited to Earle Dickson, a cotton buyer at Johnson & Johnson, who created the prototype in 1920 to help his wife Josephine, a homemaker prone to kitchen cuts, by combining adhesive tape with a gauze pad for easy application. Johnson & Johnson trademarked the product as Band-Aid in 1921 and began mass production shortly thereafter, initially offering handmade versions measuring 3 inches wide by 18 inches long that users could cut to size. Over the following decades, the design evolved, with the introduction of flexible fabric versions in the 1930s to better conform to joints and moving body parts, enhancing comfort and adhesion during daily activities.[69][70][71] Variations of adhesive bandages cater to specific needs, such as waterproof models featuring a plastic backing to repel moisture during swimming or showering, sheer or translucent options made from breathable plastic for discreet coverage, and antibiotic-impregnated types with ointments like bacitracin or Neosporin embedded in the pad to help prevent infection. These antibiotic versions provide a no-mess application of topical medication directly on the wound site, sealing out germs with a four-sided adhesive border. For application, the wound should first be cleaned with soap and water, patted dry, and the bandage pressed firmly onto the skin starting from the center pad outward to ensure full adhesion; removal involves gently peeling from one end while applying a solvent like rubbing alcohol or baby oil to loosen the adhesive and minimize residue or skin irritation.[72][73][74] The global medical tape and bandage market, including adhesive bandages, produces approximately 10 billion units annually, reflecting their widespread use in first aid kits, households, and medical settings for everyday minor injuries.[75]Liquid Bandages

Liquid bandages, also known as liquid adhesives or skin glues, are topical formulations applied directly to superficial wounds to form a thin, protective polymeric film that seals the injury and promotes healing. These products are particularly suited for minor cuts, abrasions, and lacerations where traditional bandages may be cumbersome or less effective. Unlike fabric-based dressings, liquid bandages provide seamless coverage without the need for additional materials, making them ideal for hard-to-bandage areas like joints or fingers.[76] The primary composition of modern liquid bandages consists of monomer liquids such as 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, a sterile, low-viscosity formulation that is applied via brush, dropper, or spray applicator. Upon application, the liquid rapidly polymerizes through anionic polymerization initiated by contact with moisture from the skin or wound exudate, forming a strong, flexible polymer film within seconds. This film creates a waterproof barrier that adheres to the skin, typically lasting 5 to 10 days before naturally sloughing off as the underlying skin regenerates. Earlier formulations, such as those based on nitrocellulose and solvents, originated in the 1960s with products like New-Skin, which dry to form a protective coating without polymerization.[50][77][76][78] Key advantages of liquid bandages include their ease of use, as they require no removal and minimize interference with daily activities due to their flexibility and water resistance. They also reduce the risk of scarring by maintaining a moist healing environment and providing a microbial barrier, with studies showing comparable or superior cosmetic outcomes to sutures for superficial wounds. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 2-octyl cyanoacrylate-based liquid bandages, such as Dermabond, for topical skin closure in 1998, establishing them as a safe alternative for minor wound management in clinical settings.[76][79][50] However, liquid bandages have limitations and are not suitable for deep wounds, puncture injuries, or areas with high bleeding, as they do not provide hemostasis or absorb exudate effectively. Potential adverse effects include rare instances of allergic contact dermatitis, occurring in less than 1.4% of users, typically manifesting as localized redness or irritation upon exposure to cyanoacrylate components. Medical-grade brands like Dermabond are used in surgical settings for precise closure, while over-the-counter options like New-Skin offer accessible protection for everyday minor injuries.[76][80][81]Compression Bandages

Compression bandages are specialized dressings designed to apply sustained pressure to affected areas, primarily to reduce edema, control bleeding, and promote venous return in conditions such as venous leg ulcers and lymphedema.[82] These bandages work by counteracting hydrostatic pressure in the veins, thereby facilitating wound healing and preventing fluid accumulation.[83] The primary types of compression bandages are short-stretch and long-stretch variants, distinguished by their extensibility and pressure profiles. Short-stretch bandages, with low extensibility (typically less than 100% elongation), provide high working pressure during muscle contraction (e.g., 40-60 mmHg) but low resting pressure (around 20 mmHg), making them ideal for sustained compression in immobile patients or for managing chronic edema.[84] In contrast, long-stretch bandages exhibit high elasticity (greater than 140% elongation), delivering more uniform pressure that varies with activity, which suits mobile patients but may offer less consistent support at rest.[84][85] Pressure levels in compression therapy are classified as light (20-30 mmHg), moderate (30-40 mmHg), or high (over 40 mmHg), with moderate levels recommended for optimal healing of venous ulcers by improving venous outflow without excessive strain on arterial circulation.[83] These gradients are achieved through bandage tension and layering, ensuring higher pressure at the distal end (e.g., ankle) tapering proximally to mimic physiological venous pumping.[86] Construction of compression bandages often involves crepe or cohesive materials for durability and self-adherence, applied in multiple layers to distribute pressure evenly. A common four-layer system includes: an inner absorbent layer (such as orthopaedic wool or paste-impregnated gauze like zinc oxide paste on Melolin), a crepe bandage for smoothing and absorbency, a medium-stretch elastic layer for primary compression, and an outer cohesive bandage for secure fixation via friction without adhesives. This layered approach allows customization, with the crepe layer preventing slippage and the cohesive outer layer maintaining shape during movement.[82] In clinical practice, four-layer compression systems are widely used for chronic wounds like venous leg ulcers, where Cochrane reviews indicate that compression bandages improve healing rates compared to no compression, with faster resolution of edema in multilayer applications. A meta-analysis confirms that four-layer bandaging shortens healing time (hazard ratio approximately 1.3) relative to short-stretch alternatives in some contexts, particularly for mixed-etiology wounds.[88][89] However, improper application poses risks, including ischemia from over-tightening, which can compress arteries and lead to tissue necrosis if pressures exceed 60 mmHg or if arterial insufficiency is present.[90] Clinicians must monitor for signs like pallor, pain, or reduced pulses, and contraindications include severe peripheral artery disease to avoid such complications.[90]Triangular Bandages

Triangular bandages are versatile first-aid tools designed as right-angled isosceles triangles, typically measuring 40 inches on the two equal sides and 56 inches on the hypotenuse, constructed from durable, absorbent materials such as 100% cotton muslin or calico fabric.[91][92][93] This shape allows the bandage to be folded into various configurations, including a narrow cravat by repeatedly folding along the length to create a strip approximately 4 inches wide, enabling it to serve multiple purposes without requiring specialized equipment.[94][95] The triangular bandage originated in early 19th-century military medicine, with Swiss surgeon Mathias Mayor credited for its invention in 1831 as a simple, improvisational dressing for battlefield wounds.[96] It gained widespread adoption through the efforts of Prussian surgeon Johann Friedrich August von Esmarch, who in the 1860s integrated it into soldiers' first-aid kits during the Franco-Prussian War, emphasizing its multifunctional role in hemorrhage control and limb support amid resource-scarce conditions.[97][98] By the late 19th century, illustrated versions of the bandage, printed with folding instructions, became standard in European and American military protocols, promoting self-aid and reducing reliance on medical personnel.[99][100] In modern applications, triangular bandages are essential components of standardized first-aid kits, such as those recommended by the American Red Cross, where they function as arm slings to immobilize upper limb injuries, head dressings to secure gauze over scalp wounds, and padding under tourniquets to prevent skin damage during severe bleeding control.[101][102] Their adaptability extends to retaining dressings on hands, feet, or joints, making them ideal for emergency improvisation in civilian and professional settings.[103] Application techniques involve specific folding methods to match the injury: a broad fold, achieved by folding the triangle in half along its midline to form a 4- to 6-inch wide band, provides compression for larger wounds or elevation in slings; whereas a narrow fold, created by additional lengthwise folds into a cravat, secures splints or ties dressings tightly without excessive bulk.[95][104] These techniques ensure even pressure distribution and stability, with safety pins often included to fasten the bandage securely.[105] Key advantages of triangular bandages include their compact storage, which allows multiple units to fit efficiently in portable kits while supporting a range of uses, and their reusability after washing and sterilization, as the cotton material withstands boiling or autoclaving without losing integrity.[106][107] This versatility and durability have sustained their role as a high-impact, low-cost essential in first aid since their military inception.[29][108]Tubular Bandages

Tubular bandages are seamless, elastic tubes designed to provide even pressure distribution on cylindrical body parts such as limbs or digits. They are typically constructed from knitted fabrics combining natural and synthetic materials, including cotton, viscose, elastane, and polyamide, which offer elasticity and breathability while containing natural rubber latex that may trigger allergies in sensitive individuals.[109] These bandages are sized according to a standardized diameter system ranging from A (smallest, for infant limbs or digits) to Z (largest, for adult thighs or trunks), allowing precise fitting to the circumference of the targeted area. To facilitate application without stretching or tearing the bandage, specialized applicator rods—available in metal or plastic and sized to match the bandage—are used to slide the tube over the limb.[110][111] Invented in the late 1950s, tubular bandages emerged as an innovation in medical support, with the seminal Tubigrip product developed by Ivor Stoller for Seton Products (now part of Mölnlycke Health Care), and commercialized by his son Norman Stoller in 1958, revolutionizing the application of compression without traditional wrapping techniques.[30] This design addressed the need for consistent radial pressure, drawing on compression principles to promote venous return and reduce edema, similar to those in wrap-style bandages but adapted for pre-formed tubular use on uniform shapes. Primary applications include securing absorbent dressings over wounds on arms, legs, or fingers; providing post-surgical support to stabilize tissues; and delivering uniform compression to manage swelling or strains without the need for clips, tapes, or pins.[112] Key advantages of tubular bandages lie in their efficiency and patient comfort: they can be applied in under one minute using the applicator, are reusable after washing, and distribute pressure radially to avoid hotspots, enhancing circulation while remaining breathable to prevent skin maceration from moisture buildup.[113][114] Variants include double-layered configurations, which provide enhanced support for more severe edema or joint instability by increasing compression without altering the basic tubular form.[109]Specialty Bandages

Specialty bandages encompass advanced designs tailored for complex wound management, incorporating innovative materials and structures to address limitations of conventional types, such as poor adaptability to movement or infection risks.[115] Kirigami bandages utilize laser-cut patterns inspired by the Japanese art of paper cutting to enable exceptional stretchability, achieving 200-400% elongation while preserving full coverage and adhesion on dynamic surfaces like joints. Developed in the 2010s, these bandages feature slits in thin, stretchy polymer films that allow conformal fitting without slippage, as demonstrated in research fabricating prototypes for elbows and knees.[116][115] Hydrogel bandages, particularly for burns, consist of moisture-retentive gels that provide cooling, absorb exudate, and maintain a hydrated environment to promote epithelialization and reduce scarring. These dressings, often composed of polymers like polyvinyl alcohol or alginate, adhere gently to tissue and can be transparent for monitoring, with studies showing accelerated healing in second-degree burns by delivering water and protecting against dehydration.[117][118] Integrations with negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) feature vacuum-sealed dressings that apply sub-atmospheric pressure to enhance perfusion, remove fluids, and contract the wound bed, commonly using foam or gauze sealed by adhesive films connected to a pump. This specialty approach is effective for chronic or large wounds, reducing bacterial load and hastening granulation tissue formation.[119][120] Antimicrobial chitosan-based bandages promote hemostasis by activating platelets and aggregating red blood cells through electrostatic interactions, independent of the host's coagulation cascade, leading to rapid clot formation at bleeding sites. Derived from crustacean shells, these dressings exhibit inherent antibacterial properties and have been validated in controlling severe hemorrhage in preclinical models.[121][122] Emerging 3D-printed custom bandages, prototyped in the 2020s, enable patient-specific fabrication using biocompatible hydrogels or polymers extruded layer-by-layer to match wound contours, incorporating antimicrobials or sensors for targeted therapy. These prototypes support irregular surfaces and chronic conditions, such as diabetic ulcers, by optimizing fit and drug release to prevent infection and aid re-epithelialization.[123][124]Application Techniques

General Principles

Proper hand hygiene is essential before applying any bandage to prevent the introduction of pathogens into the wound site. Healthcare providers should perform thorough handwashing with soap and water or use an alcohol-based hand rub covering all hand surfaces until dry, in accordance with World Health Organization guidelines. [125] For open wounds, a sterile technique must be employed, utilizing single-use sterile bandages and gloves to maintain an aseptic field and minimize infection risk. [126] Bandages should be applied with firm tension to provide support and compression without constricting blood flow, ensuring the wrap feels snug but allows easy movement of fingers or toes distal to the site. [127] A key assessment involves checking the pulse distal to the bandage immediately after application and periodically thereafter; if the pulse diminishes or is absent, the bandage must be loosened promptly to restore circulation. [128] When wrapping bandages, each layer should overlap the previous one by approximately 50% to achieve even coverage and prevent gaps that could lead to uneven pressure. [129] Additional padding, such as soft foam or orthopedic wool, is recommended under bony prominences like the ankles or elbows to distribute pressure and reduce the risk of pressure sores or skin breakdown. [130] Bandages on wounds should generally be changed every 24 to 48 hours or sooner if they become soiled, wet, or loose, to promote healing and prevent bacterial growth. [131] Ongoing monitoring of circulation is critical, with capillary refill time assessed by pressing on the nail bed or skin distal to the bandage; a refill of less than 2 seconds indicates adequate perfusion, while delays signal potential compromise requiring immediate adjustment. [132] Essential tools for bandage application include clean or sterile scissors for cutting materials, adhesive tape to secure edges, and disposable gloves to maintain hygiene during the process. [133] Contraindications for bandage application, particularly compression types, include severe peripheral arterial occlusive disease, where reduced blood flow could be exacerbated by any external pressure. [82]Type-Specific Methods

Roller and gauze bandages are applied using techniques that ensure even coverage and secure fixation while promoting circulation. The spiral wrap method involves starting at the distal end of the limb (farthest from the body) and wrapping the bandage with overlapping turns progressing proximally (toward the body) to create a uniform layer over the wound dressing, typically with 50% overlap to avoid gaps or excessive pressure.[134] For joints like the ankle or knee, a figure-8 wrap is preferred, beginning with a circular turn around the distal joint, then crossing the bandage in an "8" pattern to anchor and support the area without restricting movement, again directing from distal to proximal.[135] Once applied, the bandage is secured with adhesive tape at the proximal end to prevent unraveling, ensuring the wrap is snug but allows two fingers to slide underneath for comfort.[136] Adhesive bandages, often featuring a central absorbent pad, require thorough cleaning of the surrounding skin with soap and water or an antiseptic to remove debris and promote adhesion. The protective backing is peeled away, and the pad is centered directly over the wound to fully cover it without touching the injury itself, followed by firm pressure on the adhesive edges to secure the bond and minimize lifting.[137] This step ensures the bandage remains in place during daily activities while allowing the skin to breathe through the porous adhesive material.[138] Liquid bandages form a flexible, waterproof seal through a simple painting application. The applicator is shaken vigorously to mix the contents, then a thin, even layer is painted over the cleaned, approximated wound edges using short strokes, avoiding buildup that could delay drying or cause cracking.[139] One or more coats may be applied, allowing each to dry before the next for extra protection, creating a seamless barrier.[140] Compression bandages employ a multi-layer system to deliver graduated pressure, highest at the distal end and decreasing proximally for optimal venous return. The inner layer uses absorbent padding or wadding to cushion the skin and absorb exudate, applied with light tension in a spiral or figure-8 pattern; this is followed by intermediate layers of crepe or light compression for conformity, and an outer cohesive bandage that adheres to itself without sticking to skin, providing sustained pressure.[85] Limb circumference is measured at multiple points to tailor the wrap, ensuring a pressure gradient of 35-40 mmHg at the ankle for effective edema reduction without impeding arterial flow.[141][142] Triangular bandages serve versatile roles, such as slings or pressure dressings, leveraging their broad triangular shape for support. For a sling, the bandage is folded diagonally to form a cradle, slid under the injured arm with the point at the elbow, then the ends are brought over the shoulder and tied in a reef knot at the neck for secure immobilization without slippage.[143] As a pressure dressing, the corners are knotted together to create handles for tightening, and the bandage is broadly folded into a thick pad placed over the wound, then wrapped and secured to apply direct compression.[144] Tubular bandages provide easy, adjustable support via a seamless elastic tube. Using a specialized applicator tool, the bandage is slid over the limb starting distally, with the applicator maintaining even tension to avoid bunching; it is then doubled back over itself for enhanced compression and stability, overlapping by 2-3 cm to secure dressings or joints.[145] This double-layer application ensures moderate support for sprains or edema while allowing easy removal without skin irritation.[146] Specialty bandages incorporate advanced designs for specific needs, such as kirigami structures that enhance stretchability. In kirigami bandages, strategic cuts in the film are aligned parallel to the direction of anticipated movement (e.g., along joint flexion lines) to allow expansion up to 200% without delamination, applied by pressing the adhesive side onto clean skin for conformal coverage.[147] Hydrogel bandages, often in sheet form, are peeled from their backing and stuck directly onto the wound bed due to inherent adhesive properties from polymer networks, providing a moist environment while conforming to irregular surfaces without secondary fixation in many cases.[148]Medical Applications

Wound Dressing and Protection

Bandages play a crucial role in wound dressing by providing a barrier against external contaminants, absorbing exudate, and maintaining a moist environment conducive to healing. For acute wounds such as lacerations, bandages are applied after cleaning and applying an antiseptic to prevent infection by keeping the site clean and protected from bacteria. Gauze or adhesive bandages placed over antibiotic ointment are commonly used, as they allow for moisture retention while minimizing scarring and promoting epithelialization.[5] In managing chronic wounds like venous leg ulcers, compression bandages enhance venous return and reduce edema, significantly improving healing outcomes. Studies show that outpatient compression therapy results in healing rates of 57% at 10 weeks and 75% at 16 weeks, with overall success approaching 96% in suitable patients. These bandages, often multilayered, sustain pressure levels of 30-40 mmHg to optimize tissue perfusion without compromising arterial flow.[149] For burn care, non-stick dressings such as hydrogels and foams are preferred to cover partial-thickness burns, as they adhere minimally to the wound bed and facilitate painless removal during changes. These materials hydrate necrotic tissue, promote autolytic debridement, and reduce pain associated with dressing removal by avoiding disruption of newly formed granulation tissue. Hydrogels, in particular, donate moisture to dry eschar while absorbing excess exudate, supporting a balanced wound microenvironment.[150] Postoperative bandages secure surgical incisions by providing mechanical support and preventing shear forces that could lead to separation. Incisional negative-pressure wound therapy dressings have been shown to reduce the risk of dehiscence by approximately 29%, lowering incidence from 17.4% to 12.8% compared to standard dressings. This protective effect stems from even pressure distribution and removal of fluid accumulations that might otherwise promote bacterial growth or tissue stress.[151] World Health Organization guidelines on surgical site infection prevention underscore the use of layered dressings to create an optimal wound microenvironment, incorporating an interface layer (e.g., hydrocolloid) against the wound and an absorbent secondary layer to manage exudate effectively. This approach promotes moist healing, minimizes infection risk, and supports re-epithelialization without excessive moisture buildup.[152]Support and Immobilization

Bandages are essential for providing structural support and immobilization in musculoskeletal injuries, enabling non-surgical stabilization to facilitate healing and reduce pain. By limiting excessive movement, these dressings help prevent further damage while allowing controlled motion to maintain joint function. This approach is particularly valuable in acute settings, where immediate application can bridge the gap until professional medical evaluation and more definitive treatments, such as casting, are available.[153] In the treatment of sprains and strains, elastic wraps are a cornerstone of the RICE protocol—rest, ice, compression, and elevation—applied to compress the injured area and minimize swelling. These wraps, typically made from extensible materials, provide gentle pressure to support ligaments and muscles without restricting blood flow, aiding in the reduction of inflammation during the initial 48-72 hours post-injury. For example, in ankle sprains, an elastic bandage is wrapped snugly from the foot upward to promote stability and comfort during weight-bearing activities.[19][154] For suspected fractures, triangular bandages are often improvised into slings to immobilize the upper limb, supporting the arm against the chest to alleviate strain on the shoulder and elbow until radiographic confirmation and casting.[155] Tubular bandages, with their seamless cylindrical design, serve as temporary splints for limb fractures, such as those in the hand or forearm, by conforming closely to the contours and providing even compression to maintain alignment during transport or early recovery. These methods ensure provisional stability, reducing the risk of displacement prior to definitive orthopedic intervention.[156] Compression bandages offer joint support during arthritis flare-ups by applying consistent pressure to limit synovial inflammation and reduce effusion, thereby improving mobility and alleviating discomfort in affected areas like the knee or elbow. In sports medicine, kinesiology tape—a specialized elastic variant—is frequently used to enhance proprioception by stimulating skin receptors, potentially aiding in injury prevention and performance; however, clinical evidence on its efficacy remains inconsistent and debated, with some studies showing limited benefits over placebo.[157][158][159] In long-term orthopedic care, techniques such as the figure-8 wrapping for ankles provide sustained support to stabilize the joint, promoting gradual rehabilitation and helping to maintain muscle function during extended recovery periods. This method, involving crisscross application around the foot and lower leg, distributes pressure evenly to support ligament healing while allowing progressive weight-bearing exercises.[160][161][162]Complications and Best Practices

Potential Risks

Improper application of bandages, particularly when they are wrapped too tightly, can lead to circulation issues such as compartment syndrome, a condition where increased pressure within muscle compartments impairs blood flow and tissue perfusion.[163] This may manifest as the "5 Ps" of symptoms: severe pain disproportionate to the injury, pallor of the skin, pulselessness, paresthesia (numbness or tingling), and paralysis.[164] If untreated, compartment syndrome can result in permanent muscle and nerve damage.[165] Infections represent another significant risk, especially when non-sterile bandages are used on open wounds, allowing bacterial contamination and subsequent wound infection.[166] For instance, non-sterile elastic bandages have been linked to Clostridium perfringens infections in surgical sites.[167] Additionally, allergies to materials like latex or adhesives in bandages can cause contact dermatitis, characterized by itching, redness, and rash at the application site.[168][80] Prolonged bandage use can contribute to skin damage, including the development of pressure sores (also known as pressure ulcers) due to sustained localized pressure that restricts blood flow and leads to tissue breakdown.[169] Occlusive bandages, which trap moisture against the skin, may also cause maceration, where the skin becomes overly softened, whitened, and prone to breakdown from excessive hydration.[170] Allergic reactions to ingredients in antibiotic-impregnated bandages, such as neomycin, are relatively common, with an incidence of allergic contact dermatitis estimated at 1% to 10% among patch-tested individuals exposed to topical antibiotics.[171] These reactions typically present as localized inflammation, itching, or rash. Rarely, absorbent bandages left in place for extended periods on infected wounds can facilitate bacterial overgrowth, potentially leading to toxic shock syndrome, a life-threatening condition caused by toxins from Staphylococcus aureus or other pathogens.[172] Such cases have been reported in association with occlusive or absorbent dressings in burn or surgical wounds.[173]Guidelines for Use

In emergency situations involving bandaging for bleeding or trauma, healthcare providers and first responders must first assess the patient's airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) to ensure life-threatening issues are addressed before applying any dressing, as per standard first aid protocols.[174] This initial evaluation prevents exacerbation of conditions like shock or respiratory compromise during wound management.[175] Bandages and dressings should be inspected daily for signs of loosening, soiling, or moisture, with replacement occurring at least once every 24 hours or more frequently if the bandage becomes wet, loose, or saturated with exudate to maintain a clean healing environment and minimize infection risk.[6] For non-emergency wounds, evidence supports changing dressings every 1 to 2 days initially, adjusting based on wound characteristics, though proactive daily checks help identify issues early.[176] Patient education is essential for effective bandage care, including instructions to monitor for warning signs such as increased pain, numbness, tingling, swelling, redness, or discharge, which may indicate complications like impaired circulation or infection.[176] In diverse populations, such as pediatrics, bandages should be applied with a looser fit to accommodate smaller limbs and growing tissues, reducing the risk of pressure-related neurovascular compromise while ensuring security.[177] Caregivers should be taught to avoid tight wrapping and to seek prompt medical advice if symptoms arise. Professional standards for bandaging emphasize adherence to guidelines from organizations like the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which recommend selecting appropriate bandage types based on wound type and compression needs, and the American Heart Association (AHA), which integrates bandaging into broader first aid protocols.[178] Training for safe application is typically obtained through certified CPR and first aid courses, which include hands-on practice in bandaging techniques as required by OSHA standards to ensure competency in physical skills.[179] Used bandages, particularly those contaminated with blood or bodily fluids, must follow biohazard disposal protocols to prevent pathogen transmission; this involves placing them in securely closed, leak-proof red or labeled biohazard bags, avoiding double-bagging unless necessary for containment, and arranging for regulated medical waste collection rather than household disposal.[180] These measures complement efforts to mitigate risks such as infection by ensuring proper handling throughout the care process.[6]References

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/[engineering](/page/Engineering)/elastic-fabric

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/[engineering](/page/Engineering)/compression-bandage