Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Decimal

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

The decimal numeral system (also called the base-ten positional numeral system and denary /ˈdiːnəri/[1] or decanary) is the standard system for denoting integer and non-integer numbers. It is the extension to non-integer numbers (decimal fractions) of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. The way of denoting numbers in the decimal system is often referred to as decimal notation.[2]

A decimal numeral (also often just decimal or, less correctly, decimal number), refers generally to the notation of a number in the decimal numeral system. Decimals may sometimes be identified by a decimal separator (usually "." or "," as in 25.9703 or 3,1415).[3] Decimal may also refer specifically to the digits after the decimal separator, such as in "3.14 is the approximation of π to two decimals".

The numbers that may be represented exactly by a decimal of finite length are the decimal fractions. That is, fractions of the form a/10n, where a is an integer, and n is a non-negative integer. Decimal fractions also result from the addition of an integer and a fractional part; the resulting sum sometimes is called a fractional number.

Decimals are commonly used to approximate real numbers. By increasing the number of digits after the decimal separator, one can make the approximation errors as small as one wants, when one has a method for computing the new digits. In the sciences, the number of decimal places given generally gives an indication of the precision to which a quantity is known; for example, if a mass is given as 1.32 milligrams, it usually means there is reasonable confidence that the true mass is somewhere between 1.315 milligrams and 1.325 milligrams, whereas if it is given as 1.320 milligrams, then it is likely between 1.3195 and 1.3205 milligrams. The same holds in pure mathematics; for example, if one computes the square root of 22 to two digits past the decimal point, the answer is 4.69, whereas computing it to three digits, the answer is 4.690. The extra 0 at the end is meaningful, in spite of the fact that 4.69 and 4.690 are the same real number.

In principle, the decimal expansion of any real number can be carried out as far as desired past the decimal point. If the expansion reaches a point where all remaining digits are zero, then the remainder can be omitted, and such an expansion is called a terminating decimal. A repeating decimal is an infinite decimal that, after some place, repeats indefinitely the same sequence of digits (e.g., 5.123144144144144... = 5.123144).[4] An infinite decimal represents a rational number, the quotient of two integers, if and only if it is a repeating decimal or has a finite number of non-zero digits.

Origin

[edit]

Many numeral systems of ancient civilizations use ten and its powers for representing numbers, possibly because there are ten fingers on two hands and people started counting by using their fingers. Examples are firstly the Egyptian numerals, then the Brahmi numerals, Greek numerals, Hebrew numerals, Roman numerals, and Chinese numerals.[5] Very large numbers were difficult to represent in these old numeral systems, and only the best mathematicians were able to multiply or divide large numbers. These difficulties were completely solved with the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system for representing integers. This system has been extended to represent some non-integer numbers, called decimal fractions or decimal numbers, for forming the decimal numeral system.[5]

Decimal notation

[edit]For writing numbers, the decimal system uses ten decimal digits, a decimal mark, and, for negative numbers, a minus sign "−". The decimal digits are 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9;[6] the decimal separator is the dot "." in many countries (mostly English-speaking),[7] and a comma "," in other countries.[3]

For representing a non-negative number, a decimal numeral consists of

- either a (finite) sequence of digits (such as "2017"), where the entire sequence represents an integer:

- or a decimal mark separating two sequences of digits (such as "20.70828")

- .

If m > 0, that is, if the first sequence contains at least two digits, it is generally assumed that the first digit am is not zero. In some circumstances it may be useful to have one or more 0's on the left; this does not change the value represented by the decimal: for example, 3.14 = 03.14 = 003.14. Similarly, if the final digit on the right of the decimal mark is zero—that is, if bn = 0—it may be removed; conversely, trailing zeros may be added after the decimal mark without changing the represented number; [note 1] for example, 15 = 15.0 = 15.00 and 5.2 = 5.20 = 5.200.

For representing a negative number, a minus sign is placed before am.

The numeral represents the number

- .

The integer part or integral part of a decimal numeral is the integer written to the left of the decimal separator (see also truncation). For a non-negative decimal numeral, it is the largest integer that is not greater than the decimal. The part from the decimal separator to the right is the fractional part, which equals the difference between the numeral and its integer part.

When the integral part of a numeral is zero, it may occur, typically in computing, that the integer part is not written (for example, .1234, instead of 0.1234). In normal writing, this is generally avoided, because of the risk of confusion between the decimal mark and other punctuation.

In brief, the contribution of each digit to the value of a number depends on its position in the numeral. That is, the decimal system is a positional numeral system.

Decimal fractions

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

Decimal fractions (sometimes called decimal numbers, especially in contexts involving explicit fractions) are the rational numbers that may be expressed as a fraction whose denominator is a power of ten.[8] For example, the decimal expressions represent the fractions 8/10, 1489/100, 79/100000, +1618/1000 and +314159/100000, and therefore denote decimal fractions. An example of a fraction that cannot be represented by a decimal expression (with a finite number of digits) is 1/3, 3 not being a power of 10.

More generally, a decimal with n digits after the separator (a point or comma) represents the fraction with denominator 10n, whose numerator is the integer obtained by removing the separator.

It follows that a number is a decimal fraction if and only if it has a finite decimal representation.

Expressed as fully reduced fractions, the decimal numbers are those whose denominator is a product of a power of 2 and a power of 5. Thus the smallest denominators of decimal numbers are

Approximation using decimal numbers

[edit]Decimal numerals do not allow an exact representation for all real numbers. Nevertheless, they allow approximating every real number with any desired accuracy, e.g., the decimal 3.14159 approximates π, being less than 10−5 off; so decimals are widely used in science, engineering and everyday life.

More precisely, for every real number x and every positive integer n, there are two decimals L and u with at most n digits after the decimal mark such that L ≤ x ≤ u and (u − L) = 10−n.

Numbers are very often obtained as the result of measurement. As measurements are subject to measurement uncertainty with a known upper bound, the result of a measurement is well-represented by a decimal with n digits after the decimal mark, as soon as the absolute measurement error is bounded from above by 10−n. In practice, measurement results are often given with a certain number of digits after the decimal point, which indicate the error bounds. For example, although 0.080 and 0.08 denote the same number, the decimal numeral 0.080 suggests a measurement with an error less than 0.001, while the numeral 0.08 indicates an absolute error bounded by 0.01. In both cases, the true value of the measured quantity could be, for example, 0.0803 or 0.0796 (see also significant figures).

Infinite decimal expansion

[edit]For a real number x and an integer n ≥ 0, let [x]n denote the (finite) decimal expansion of the greatest number that is not greater than x that has exactly n digits after the decimal mark. Let di denote the last digit of [x]i. It is straightforward to see that [x]n may be obtained by appending dn to the right of [x]n−1. This way one has

- [x]n = [x]0.d1d2...dn−1dn,

and the difference of [x]n−1 and [x]n amounts to

- ,

which is either 0, if dn = 0, or gets arbitrarily small as n tends to infinity. According to the definition of a limit, x is the limit of [x]n when n tends to infinity. This is written asor

- x = [x]0.d1d2...dn...,

which is called an infinite decimal expansion of x.

Conversely, for any integer [x]0 and any sequence of digits the (infinite) expression [x]0.d1d2...dn... is an infinite decimal expansion of a real number x. This expansion is unique if neither all dn are equal to 9 nor all dn are equal to 0 for n large enough (for all n greater than some natural number N).

If all dn for n > N equal to 9 and [x]n = [x]0.d1d2...dn, the limit of the sequence is the decimal fraction obtained by replacing the last digit that is not a 9, i.e.: dN, by dN + 1, and replacing all subsequent 9s by 0s (see 0.999...).

Any such decimal fraction, i.e.: dn = 0 for n > N, may be converted to its equivalent infinite decimal expansion by replacing dN by dN − 1 and replacing all subsequent 0s by 9s (see 0.999...).

In summary, every real number that is not a decimal fraction has a unique infinite decimal expansion. Each decimal fraction has exactly two infinite decimal expansions, one containing only 0s after some place, which is obtained by the above definition of [x]n, and the other containing only 9s after some place, which is obtained by defining [x]n as the greatest number that is less than x, having exactly n digits after the decimal mark.

Rational numbers

[edit]Long division allows computing the infinite decimal expansion of a rational number. If the rational number is a decimal fraction, the division stops eventually, producing a decimal numeral, which may be prolongated into an infinite expansion by adding infinitely many zeros. If the rational number is not a decimal fraction, the division may continue indefinitely. However, as all successive remainders are less than the divisor, there are only a finite number of possible remainders, and after some place, the same sequence of digits must be repeated indefinitely in the quotient. That is, one has a repeating decimal. For example,

- 1/81 = 0. 012345679 012... (with the group 012345679 indefinitely repeating).

The converse is also true: if, at some point in the decimal representation of a number, the same string of digits starts repeating indefinitely, the number is rational.

| For example, if x is | 0.4156156156... |

| then 10,000x is | 4156.156156156... |

| and 10x is | 4.156156156... |

| so 10,000x − 10x, i.e. 9,990x, is | 4152.000000000... |

| and x is | 4152/9990 |

or, dividing both numerator and denominator by 6, 692/1665.

Decimal computation

[edit]

Most modern computer hardware and software systems commonly use a binary representation internally (although many early computers, such as the ENIAC or the IBM 650, used decimal representation internally).[9] For external use by computer specialists, this binary representation is sometimes presented in the related octal or hexadecimal systems.

For most purposes, however, binary values are converted to or from the equivalent decimal values for presentation to or input from humans; computer programs express literals in decimal by default. (123.1, for example, is written as such in a computer program, even though many computer languages are unable to encode that number precisely.)

Both computer hardware and software also use internal representations which are effectively decimal for storing decimal values and doing arithmetic. Often this arithmetic is done on data which are encoded using some variant of binary-coded decimal,[10][11] especially in database implementations, but there are other decimal representations in use (including decimal floating point such as in newer revisions of the IEEE 754 Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic).[12]

Decimal arithmetic is used in computers so that decimal fractional results of adding (or subtracting) values with a fixed length of their fractional part always are computed to this same length of precision. This is especially important for financial calculations, e.g., requiring in their results integer multiples of the smallest currency unit for book keeping purposes. This is not possible in binary, because the negative powers of have no finite binary fractional representation; and is generally impossible for multiplication (or division).[13][14] See Arbitrary-precision arithmetic for exact calculations.

History

[edit]

Many ancient cultures calculated with numerals based on ten, perhaps because two human hands have ten fingers.[15] Standardized weights used in the Indus Valley Civilisation (c. 3300–1300 BCE) were based on the ratios: 1/20, 1/10, 1/5, 1/2, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500, while their standardized ruler – the Mohenjo-daro ruler – was divided into ten equal parts.[16][17][18] Egyptian hieroglyphs, in evidence since around 3000 BCE, used a purely decimal system,[19] as did the Linear A script (c. 1800–1450 BCE) of the Minoans[20][21] and the Linear B script (c. 1400–1200 BCE) of the Mycenaeans. The Únětice culture in central Europe (2300-1600 BC) used standardised weights and a decimal system in trade.[22] The number system of classical Greece also used powers of ten, including an intermediate base of 5, as did Roman numerals.[23] Notably, the polymath Archimedes (c. 287–212 BCE) invented a decimal positional system in his Sand Reckoner which was based on 108.[23][24] Hittite hieroglyphs (since 15th century BCE) were also strictly decimal.[25]

The Egyptian hieratic numerals, the Greek alphabet numerals, the Hebrew alphabet numerals, the Roman numerals, the Chinese numerals and early Indian Brahmi numerals are all non-positional decimal systems, and required large numbers of symbols. For instance, Egyptian numerals used different symbols for 10, 20 to 90, 100, 200 to 900, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, 4,000, to 10,000.[26] The world's earliest positional decimal system was the Chinese rod calculus.[27]

Upper row vertical form

Lower row horizontal form

History of decimal fractions

[edit]

Starting from the 2nd century BCE, some Chinese units for length were based on divisions into ten; by the 3rd century CE these metrological units were used to express decimal fractions of lengths, non-positionally.[28] Calculations with decimal fractions of lengths were performed using positional counting rods, as described in the 3rd–5th century CE Sunzi Suanjing. The 5th century CE mathematician Zu Chongzhi calculated a 7-digit approximation of π. Qin Jiushao's book Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections (1247) explicitly writes a decimal fraction representing a number rather than a measurement, using counting rods.[29] The number 0.96644 is denoted

Historians of Chinese science have speculated that the idea of decimal fractions may have been transmitted from China to the Middle East.[27]

Al-Khwarizmi introduced fractions to Islamic countries in the early 9th century CE, written with a numerator above and denominator below, without a horizontal bar. This form of fraction remained in use for centuries.[27][30]

Positional decimal fractions appear for the first time in a book by the Arab mathematician Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi written in the 10th century.[31] The Jewish mathematician Immanuel Bonfils used decimal fractions around 1350 but did not develop any notation to represent them.[32] The Persian mathematician Jamshid al-Kashi used, and claimed to have discovered, decimal fractions in the 15th century.[31]

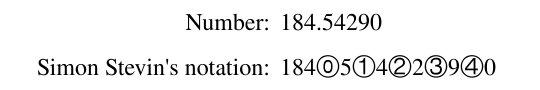

A forerunner of modern European decimal notation was introduced by Simon Stevin in the 16th century. Stevin's influential booklet De Thiende ("the art of tenths") was first published in Dutch in 1585 and translated into French as La Disme.[33]

John Napier introduced using the period (.) to separate the integer part of a decimal number from the fractional part in his book on constructing tables of logarithms, published posthumously in 1620.[34]: p. 8, archive p. 32

Natural languages

[edit]A method of expressing every possible natural number using a set of ten symbols emerged in India.[35] Several Indian languages show a straightforward decimal system. Dravidian languages have numbers between 10 and 20 expressed in a regular pattern of addition to 10.[36]

The Hungarian language also uses a straightforward decimal system. All numbers between 10 and 20 are formed regularly (e.g. 11 is expressed as "tizenegy" literally "one on ten"), as with those between 20 and 100 (23 as "huszonhárom" = "three on twenty").

A straightforward decimal rank system with a word for each order (10 十, 100 百, 1000 千, 10,000 万), and in which 11 is expressed as ten-one and 23 as two-ten-three, and 89,345 is expressed as 8 (ten thousands) 万 9 (thousand) 千 3 (hundred) 百 4 (tens) 十 5 is found in Chinese, and in Vietnamese with a few irregularities. Japanese, Korean, and Thai have imported the Chinese decimal system. Many other languages with a decimal system have special words for the numbers between 10 and 20, and decades. For example, in English 11 is "eleven" not "ten-one" or "one-teen".

Incan languages such as Quechua and Aymara have an almost straightforward decimal system, in which 11 is expressed as ten with one and 23 as two-ten with three.

Some psychologists suggest irregularities of the English names of numerals may hinder children's counting ability.[37]

Other bases

[edit]|

Units of information |

| Information-theoretic |

|---|

| Data storage |

| Quantum information |

Some cultures do, or did, use other bases of numbers.

- Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures such as the Maya used a base-20 system (perhaps based on using all twenty fingers and toes).

- The Yuki language in California and the Pamean languages[38] in Mexico have octal (base-8) systems because the speakers count using the spaces between their fingers rather than the fingers themselves.[39]

- The existence of a non-decimal base in the earliest traces of the Germanic languages is attested by the presence of words and glosses meaning that the count is in decimal (cognates to "ten-count" or "tenty-wise"); such would be expected if normal counting is not decimal, and unusual if it were.[40][41] Where this counting system is known, it is based on the "long hundred" = 120, and a "long thousand" of 1200. The descriptions like "long" only appear after the "small hundred" of 100 appeared with the Christians. Gordon's Introduction to Old Norse[42] gives number names that belong to this system. An expression cognate to 'one hundred and eighty' translates to 200, and the cognate to 'two hundred' translates to 240. Goodare[43] details the use of the long hundred in Scotland in the Middle Ages, giving examples such as calculations where the carry implies i C (i.e. one hundred) as 120, etc. That the general population were not alarmed to encounter such numbers suggests common enough use. It is also possible to avoid hundred-like numbers by using intermediate units, such as stones and pounds, rather than a long count of pounds. Goodare gives examples of numbers like vii score, where one avoids the hundred by using extended scores. There is also a paper by W.H. Stevenson, on 'Long Hundred and its uses in England'.[44][45]

- Many or all of the Chumashan languages originally used a base-4 counting system, in which the names for numbers were structured according to multiples of 4 and 16.[46]

- Many languages[47] use quinary (base-5) number systems, including Gumatj, Nunggubuyu,[48] Kuurn Kopan Noot[49] and Saraveca. Of these, Gumatj is the only true 5–25 language known, in which 25 is the higher group of 5.

- Some Nigerians use duodecimal systems.[50] So did some small communities in India and Nepal, as indicated by their languages.[51]

- The Huli language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have base-15 numbers.[52] Ngui means 15, ngui ki means 15 × 2 = 30, and ngui ngui means 15 × 15 = 225.

- Umbu-Ungu, also known as Kakoli, is reported to have base-24 numbers.[53] Tokapu means 24, tokapu talu means 24 × 2 = 48, and tokapu tokapu means 24 × 24 = 576.

- Ngiti is reported to have a base-32 number system with base-4 cycles.[47]

- The Ndom language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have base-6 numerals.[54] Mer means 6, mer an thef means 6 × 2 = 12, nif means 36, and nif thef means 36×2 = 72.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "denary". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Yong, Lam Lay; Se, Ang Tian (April 2004). Fleeting Footsteps. World Scientific. 268. doi:10.1142/5425. ISBN 978-981-238-696-0. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Weisstein, Eric W. (March 10, 2022). "Decimal Point". Wolfram MathWorld. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ The vinculum (overline) in 5.123144 indicates that the '144' sequence repeats indefinitely, i.e. 5.123144144144144....

- ^ a b Lockhart, Paul (2017). Arithmetic. Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97223-0.

- ^ In some countries, such as Arabic-speaking ones, other glyphs are used for the digits

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Decimal". mathworld.wolfram.com. Archived from the original on 2020-03-18. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- ^ "Decimal Fraction". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Archived from the original on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ "Fingers or Fists? (The Choice of Decimal or Binary Representation)", Werner Buchholz, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 2 #12, pp. 3–11, ACM Press, December 1959.

- ^ Schmid, Hermann (1983) [1974]. Decimal Computation (1 (reprint) ed.). Malabar, Florida: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89874-318-4.

- ^ Schmid, Hermann (1974). Decimal Computation (1st ed.). Binghamton, New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-76180-X.

- ^ Decimal Floating-Point: Algorism for Computers, Cowlishaw, Mike F., Proceedings 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic, ISBN 0-7695-1894-X, pp. 104–11, IEEE Comp. Soc., 2003

- ^ "Decimal Arithmetic – FAQ". Archived from the original on 2009-04-29. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ^ Decimal Floating-Point: Algorism for Computers Archived 2003-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, Cowlishaw, M. F., Proceedings 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic (ARITH 16 Archived 2010-08-19 at the Wayback Machine), ISBN 0-7695-1894-X, pp. 104–11, IEEE Comp. Soc., June 2003

- ^ Dantzig, Tobias (1954), Number / The Language of Science (4th ed.), The Free Press (Macmillan Publishing Co.), p. 12, ISBN 0-02-906990-4

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Sergent, Bernard (1997), Genèse de l'Inde (in French), Paris: Payot, p. 113, ISBN 2-228-89116-9

- ^ Coppa, A.; et al. (2006). "Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry: Flint tips were surprisingly effective for drilling tooth enamel in a prehistoric population". Nature. 440 (7085): 755–56. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..755C. doi:10.1038/440755a. PMID 16598247. S2CID 6787162.

- ^ Bisht, R. S. (1982), "Excavations at Banawali: 1974–77", in Possehl, Gregory L. (ed.), Harappan Civilisation: A Contemporary Perspective, New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., pp. 113–24

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp. 200–13 (Egyptian Numerals)

- ^ Graham Flegg: Numbers: their history and meaning, Courier Dover Publications, 2002, ISBN 978-0-486-42165-0, p. 50

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp. 213–18 (Cretan numerals)

- ^ Krause, Harald; Kutscher, Sabrina (2017). "Spangenbarrenhort Oberding: Zusammenfassung und Ausblick". Spangenbarrenhort Oberding. Museum Erding. pp. 238–243. ISBN 978-3-9817606-5-1.

- ^ a b "Greek numbers". Archived from the original on 2019-07-21. Retrieved 2019-07-21.

- ^ Menninger, Karl: Zahlwort und Ziffer. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Zahl, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 3rd. ed., 1979, ISBN 3-525-40725-4, pp. 150–53

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp. 218f. (The Hittite hieroglyphic system)

- ^ Lam Lay Yong et al. The Fleeting Footsteps pp. 137–39

- ^ a b c Lam Lay Yong, "The Development of Hindu–Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic", Chinese Science, 1996 p. 38, Kurt Vogel notation

- ^ Joseph Needham (1959). "19.2 Decimals, Metrology, and the Handling of Large Numbers". Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. III, "Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth". Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–90.

- ^ Jean-Claude Martzloff, A History of Chinese Mathematics, Springer 1997 ISBN 3-540-33782-2

- ^ Lay Yong, Lam. "A Chinese Genesis, Rewriting the history of our numeral system". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 38: 101–08.

- ^ a b Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". In Katz, Victor J. (ed.). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- ^ Gandz, S.: The invention of the decimal fractions and the application of the exponential calculus by Immanuel Bonfils of Tarascon (c. 1350), Isis 25 (1936), 16–45.

- ^ B. L. van der Waerden (1985). A History of Algebra. From Khwarizmi to Emmy Noether. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ Napier, John (1889) [1620]. The Construction of the Wonderful Canon of Logarithms. Translated by Macdonald, William Rae. Edinburgh: Blackwood & Sons – via Internet Archive.

In numbers distinguished thus by a period in their midst, whatever is written after the period is a fraction, the denominator of which is unity with as many cyphers after it as there are figures after the period.

- ^ "Indian numerals". Ancient Indian mathematics.

- ^ "Appendix:Cognate sets for Dravidian languages", Wiktionary, the free dictionary, 2024-09-25, retrieved 2024-11-09

- ^ Azar, Beth (1999). "English words may hinder math skills development". APA Monitor. 30 (4). Archived from the original on 2007-10-21.

- ^ Avelino, Heriberto (2006). "The typology of Pame number systems and the limits of Mesoamerica as a linguistic area" (PDF). Linguistic Typology. 10 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1515/LINGTY.2006.002. S2CID 20412558. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-07-12.

- ^ Marcia Ascher. "Ethnomathematics: A Multicultural View of Mathematical Ideas". The College Mathematics Journal. JSTOR 2686959.

- ^ McClean, R. J. (July 1958), "Observations on the Germanic numerals", German Life and Letters, 11 (4): 293–99, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0483.1958.tb00018.x,

Some of the Germanic languages appear to show traces of an ancient blending of the decimal with the vigesimal system

. - ^ Voyles, Joseph (October 1987), "The cardinal numerals in pre-and proto-Germanic", The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 86 (4): 487–95, JSTOR 27709904.

- ^ Gordon's Introduction to Old Norse Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine p. 293

- ^ Goodare, Julian (November 1994). "The long hundred in medieval and early modern Scotland". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 123: 395–418. doi:10.9750/psas.123.395.418.

- ^ Stevenson, W.H. (1890). "The Long Hundred and its uses in England". Archaeological Review. December 1889: 313–22.

- ^ Poole, Reginald Lane (2006). The Exchequer in the twelfth century : the Ford lectures delivered in the University of Oxford in Michaelmas term, 1911. Clark, NJ: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 1-58477-658-7. OCLC 76960942.

- ^ There is a surviving list of Ventureño language number words up to 32 written down by a Spanish priest ca. 1819. "Chumashan Numerals" by Madison S. Beeler, in Native American Mathematics, edited by Michael P. Closs (1986), ISBN 0-292-75531-7.

- ^ a b Hammarström, Harald (17 May 2007). "Rarities in Numeral Systems". In Wohlgemuth, Jan; Cysouw, Michael (eds.). Rethinking Universals: How rarities affect linguistic theory (PDF). Empirical Approaches to Language Typology. Vol. 45. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter (published 2010). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2007.

- ^ Harris, John (1982). Hargrave, Susanne (ed.). "Facts and fallacies of aboriginal number systems" (PDF). Work Papers of SIL-AAB Series B. 8: 153–81. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-31.

- ^ Dawson, J. "Australian Aborigines: The Languages and Customs of Several Tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria (1881), p. xcviii.

- ^ Matsushita, Shuji (1998). Decimal vs. Duodecimal: An interaction between two systems of numeration. 2nd Meeting of the AFLANG, October 1998, Tokyo. Archived from the original on 2008-10-05. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ Mazaudon, Martine (2002). "Les principes de construction du nombre dans les langues tibéto-birmanes". In François, Jacques (ed.). La Pluralité (PDF). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 91–119. ISBN 90-429-1295-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-28. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- ^ Cheetham, Brian (1978). "Counting and Number in Huli". Papua New Guinea Journal of Education. 14: 16–35. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

- ^ Bowers, Nancy; Lepi, Pundia (1975). "Kaugel Valley systems of reckoning" (PDF). Journal of the Polynesian Society. 84 (3): 309–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-04.

- ^ Owens, Kay (2001), "The Work of Glendon Lean on the Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania", Mathematics Education Research Journal, 13 (1): 47–71, Bibcode:2001MEdRJ..13...47O, doi:10.1007/BF03217098, S2CID 161535519, archived from the original on 2015-09-26

Decimal

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Origin

The term "decimal" originates from the Late Latin decimalis, meaning "of tenths" or "pertaining to a tenth," derived from decimus ("tenth") and ultimately from decem ("ten").[6][7] This etymology directly links to the base-10 structure of the decimal system, where place values represent powers of ten. The conceptual roots of the base-10 system trace back to ancient human counting practices, likely influenced by the anatomy of the hands with ten fingers, facilitating tallying in groups of ten.[8] Early evidence of advanced numeral systems appears in Mesopotamian cuneiform records, where a base-60 (sexagesimal) system was used. The Babylonians developed positional notation in this base around the 2nd millennium BCE.[9] The positional decimal numeral system, incorporating zero as a placeholder, emerged in ancient India during the Gupta period (c. 320–550 CE), with significant formalization by the mathematician Brahmagupta in his 628 CE treatise Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta.[10] In this work, Brahmagupta not only described the decimal place-value system but also defined arithmetic operations involving zero, such as 0 + a = a and a - a = 0, establishing its mathematical rigor.[11] This Indian innovation built on earlier numeral traditions, enabling efficient representation of large numbers and fractions through positional values. The decimal system was transmitted from India to the Islamic world in the 9th century through the Persian scholar Al-Khwarizmi's treatise On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals (c. 825 CE), which detailed the Hindu-Arabic digits and their use in computation.[12] From there, it reached Europe via the Italian mathematician Fibonacci's Liber Abaci in 1202, which popularized the system among merchants and scholars by demonstrating its superiority for practical calculations.[13] This dissemination laid the foundation for the decimal system's adoption as the global standard in mathematics and everyday use.Basic Principles

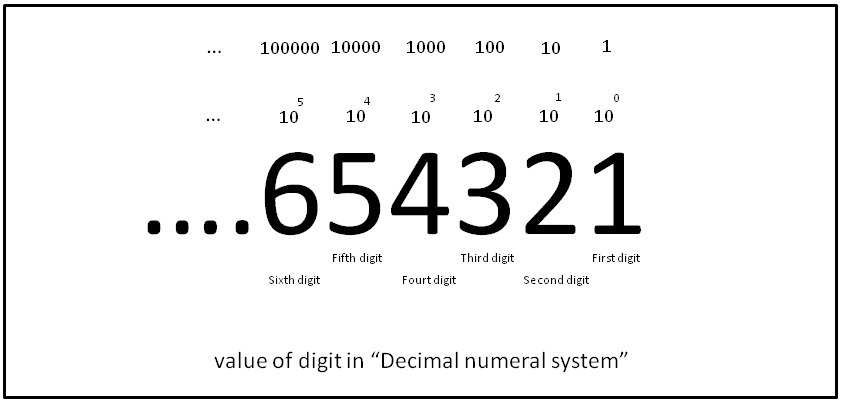

The decimal system, also known as the base-10 numeral system, is a positional notation where the value of each digit is determined by its position relative to the others, with each position representing a successive power of 10 starting from the rightmost digit as .[14] In this system, the digits range from 0 to 9, and the position of a digit multiplies its face value by the corresponding power of 10, enabling compact representation of numbers.[15] Place values in the decimal system are structured as follows: the rightmost position is the units place (), the next is the tens place (), followed by the hundreds place (), and so on for higher powers.[16] For example, the number 123 is expressed mathematically as .[16] This positional weighting allows for efficient encoding of numerical values without requiring unique symbols for each quantity. The digit zero plays a dual role in the decimal system: it represents the additive identity (the number zero itself) and serves as a placeholder to indicate the absence of value in a given position, thereby distinguishing between numbers like 10 (one ten and zero units) and 100 (one hundred and zero tens and units).[17] Without zero as a placeholder, the system's ability to denote varying magnitudes through position alone would be compromised, as seen in the differentiation between 10 and 100.[18] Compared to non-positional systems like Roman numerals, which rely on additive and subtractive combinations of symbols without fixed place values, the decimal system offers greater efficiency for representing and manipulating large numbers, as it requires fewer symbols and supports straightforward arithmetic operations.[19] This positional efficiency contributed to the widespread adoption of decimal notation following its development in ancient India around the 5th to 7th centuries.[17]Notation and Representation

Integer Notation

In the decimal system, integers are represented using digits from 0 to 9 arranged in a sequence, with the value determined by reading the digits from left to right and assigning increasing place values based on powers of 10 starting from the rightmost digit. The rightmost position holds the units place (10^0), the next to the left is the tens place (10^1), followed by the hundreds place (10^2), thousands place (10^3), and so on. For example, the integer 456 is calculated as .[20] For a larger number, the integer 4567 is calculated as , which equals four thousand five hundred sixty-seven.[21][22] Leading zeros in integer notation are insignificant and do not alter the numerical value, functioning only as placeholders to maintain alignment or fixed-width formatting; thus, 04567 is equivalent to 4567.[23] Trailing zeros, in contrast, are integral to the representation in context, explicitly indicating that the integer is a multiple of the corresponding power of 10 and contributing to its exact magnitude; for instance, 45670 includes two trailing zeros, signifying it is 4567 multiplied by 100.[24] For readability, especially with large integers, thousand separators such as commas or spaces are commonly inserted every three digits from the right, grouping the digits into thousands; 1,000,000 (or 1 000 000) denotes one million.[25] Very large integers are often expressed in scientific notation as , where and is a non-negative integer exponent, to compactly convey scale; for example, 300,000,000 is written as .[26] This integer-focused notation extends to fractional representations by placing a decimal point after the units digit.Fractional Notation

In the decimal system, the decimal point serves to separate the integer part from the fractional part of a number, allowing for the representation of values between whole numbers. For instance, the number 3.14 indicates 3 units plus a fractional component, expressed mathematically as . This notation extends the place-value system to the right of the point, where each position represents a negative power of 10.[27] Decimal fractions (also called decimal numbers) represent parts of a unit using the base-10 system. Each position after the decimal point corresponds to a fraction of a whole:- The first place is tenths ( or décimas in Spanish), representing 1/10.

- The second place is hundredths ( or centésimas), representing 1/100.

- The third place is thousandths ( or milésimas), representing 1/1000.

- 0.5 = 5 tenths = 5/10 = 1/2

- 0.75 = 75 hundredths = 75/100 = 3/4

- 2.3 = 2 units + 3 tenths = 2 + 3/10 = 23/10

Approximations and Rounding

In practical contexts such as measurements and calculations, finite decimal approximations are essential for representing irrational numbers or lengthy decimals with sufficient accuracy while simplifying computations and reporting./04:_The_Basics_of_Chemistry/4.06:_Significant_Figures_and_Rounding) This process minimizes the impact of infinite expansions typical of irrational numbers, enabling efficient use in fields like engineering and science.[32] Rounding is the primary method for decimal approximation, where a number is adjusted to a specified place value based on the digit immediately following it. The standard rule, known as "round half up," instructs that if this digit is 5 or greater, the preceding digit is increased by one, while digits less than 5 are discarded; for example, 3.1416 rounded to two decimal places becomes 3.14. This applies similarly to rounding to the nearest integer (e.g., 4.7 ≈ 5) or tenth (e.g., 2.34 ≈ 2.3), ensuring the approximation is the closest value at the desired precision.[33] Truncation, in contrast, simply discards digits beyond the specified place without adjustment, resulting in a consistently lower approximation for positive numbers compared to rounding. For instance, the value of π ≈ 3.14159 truncated to two decimal places yields 3.14, the same as rounding in this case, but truncating 3.149 to two decimals gives 3.14 while rounding gives 3.15.[32] Truncation introduces a systematic bias toward smaller values, making rounding preferable for balanced accuracy in most applications. Approximations often incorporate significant figures, which count the meaningful digits in a number to reflect measurement precision; trailing zeros after the decimal point are significant if explicitly indicated. For example, 2.998 approximated to three significant figures becomes 3.00, preserving the implied precision.[34] This approach ensures that reported decimals align with the reliability of the original data, avoiding overstatement of accuracy./04:_The_Basics_of_Chemistry/4.06:_Significant_Figures_and_Rounding)Expansions and Properties

Terminating and Repeating Decimals

Decimal expansions of rational numbers are classified as either terminating or repeating, depending on the prime factorization of the denominator when the fraction is expressed in lowest terms.[35] A terminating decimal ends after a finite number of digits after the decimal point, equivalent to a fraction where the denominator's prime factors are solely 2 and/or 5. For instance, , since 4 = , terminates after two places. This occurs because the base-10 system aligns with powers of 10, which factor as , allowing exact representation without remainder.[36] Repeating decimals, in contrast, feature a sequence of digits that cycles indefinitely and arise when the denominator in lowest terms includes prime factors other than 2 or 5. These are subdivided into pure repeating decimals, where the repetition begins immediately after the decimal point, and mixed (or eventually repeating) decimals, where a non-repeating prefix precedes the cycle. A pure repeating example is , with the single digit 3 repeating from the start, as 3 is coprime to 10. For a mixed case, , the non-repeating digit 1 follows from the factor of 2 in 6 = 2 × 3, after which 6 repeats.[37] Standard notation for repeating decimals employs a vinculum (horizontal bar) over the repeating sequence to denote the cycle, such as for 0.333... or for the mixed form. Alternatively, parentheses with dots may indicate repetition, like 0.3̇ for pure or 0.16̇ for mixed, though the bar is more common in formal mathematical writing.[38] The period length, or number of digits in the repeating block, is the smallest positive integer such that , where is the part of the denominator coprime to 10 (after removing factors of 2 and 5). This multiplicative order of 10 modulo determines the cycle's duration; for example, in , the period is 6, as the order of 10 modulo 7 is 6.[39]Rational and Irrational Numbers

A decimal expansion is terminating if it ends after a finite number of digits, such as 0.5 for 1/2, and repeating if a sequence of digits recurs indefinitely, such as 0.333... for 1/3. All numbers with terminating or repeating decimal expansions are rational, meaning they can be expressed as a fraction p/q where p and q are integers and q ≠ 0.[40] This follows from the long division process used to compute the decimal expansion of p/q: the remainders at each step are integers between 0 and q-1, a finite set, so by the pigeonhole principle, either a remainder of 0 is reached (terminating) or a remainder repeats (causing the digits to repeat from that point).[41] Conversely, every rational number has a decimal expansion that is either terminating or eventually repeating, establishing the equivalence: a real number is rational if and only if its decimal expansion terminates or repeats.[42] Terminating decimals can be viewed as repeating with an infinite sequence of zeros, aligning with this characterization. Irrational numbers, by contrast, have decimal expansions that are non-terminating and non-repeating, continuing infinitely without any periodic pattern.[43] Classic examples of irrationals include the square root of 2, with expansion √2 ≈ 1.414213562373095..., proven irrational by contradiction assuming it equals p/q leads to an integer being both even and odd.[44] Similarly, π ≈ 3.141592653589793... is irrational, as established by Johann Lambert in 1761 via continued fractions showing it cannot be rational.[43] The base of the natural logarithm, e ≈ 2.718281828459045..., is also irrational, with its non-repeating expansion derived from the infinite series ∑(1/n!) for n=0 to ∞.[45] Continued fraction approximations provide a method to generate successively better rational estimates for irrationals like these, revealing their infinite, non-periodic nature.[41]Infinite Series Representation

Any infinite decimal expansion of a real number between 0 and 1 can be expressed as an infinite series: , where each is a digit from 0 to 9.[46] This representation leverages the place-value system, allowing the decimal to be analyzed as a sum of terms with decreasing powers of 10.[46] For repeating decimals, this series takes the form of a geometric series, enabling exact summation. Consider the repeating decimal , which corresponds to the fraction ; it can be written as the infinite sum , a geometric series with first term and common ratio . The sum is .[47] In general, for a pure repeating decimal with a block of length , the value is given by the formula , where is the integer formed by the repeating block. This derives directly from the geometric series sum .[47] Such series representations extend to irrational numbers, whose non-repeating decimal expansions arise from infinite series without periodic structure. For instance, the Leibniz formula provides a series for : , which can be used to compute successive decimal digits of by partial sums in base 10.[48] This approach, though slowly convergent, illustrates how infinite series facilitate decimal approximations of transcendental constants like .[49]Computation and Applications

Arithmetic Operations

Addition and subtraction of decimal numbers follow procedures similar to those for integers, with the key step of aligning the decimal points to ensure place value accuracy. To add or subtract, write the numbers in a vertical column with their decimal points lined up, adding zeros to the right of shorter decimals if necessary to match lengths. Then, perform the addition or subtraction column by column from right to left, carrying or borrowing as needed just as with whole numbers, and place the decimal point in the result directly below the aligned points in the addends or minuend. For example, adding 2.3 and 1.45 involves rewriting 2.3 as 2.30 and aligning as follows: 2.30

+ 1.45

------

3.75

2.30

+ 1.45

------

3.75

Decimal Arithmetic in Computing

In computer systems, decimal arithmetic is primarily handled through floating-point representations defined by the IEEE 754 standard, which predominantly uses binary formats for efficiency. These binary floating-point formats, such as single-precision (32-bit) and double-precision (64-bit), encode numbers with a sign bit, an exponent, and a significand in base-2, but many decimal fractions like 0.1 cannot be represented exactly because they do not terminate in binary. For instance, 0.1 in double-precision IEEE 754 approximates to 0.1000000000000000055511151231257827021181583404541015625, introducing small rounding errors that accumulate in calculations.[57][58] A well-known consequence of these inexact representations is that simple operations like 0.1 + 0.2 do not yield exactly 0.3 in binary floating-point arithmetic, resulting instead in approximately 0.30000000000000004 due to the summation of approximation errors. This issue arises because both operands are inexact, and the addition propagates the discrepancies, which is particularly problematic in applications requiring precise decimal results, such as financial computations where even minor errors can lead to significant discrepancies over many transactions.[59][57] To address these limitations, the IEEE 754-2008 revision introduced dedicated decimal floating-point formats, including decimal32 (32 bits, 7 decimal digits of precision), decimal64 (64 bits, 16 digits), and decimal128 (128 bits, 34 digits), which use base-10 encoding to represent decimal numbers exactly where possible and perform arithmetic directly in decimal radix. These formats mitigate binary rounding errors by avoiding conversions between bases, making them suitable for financial and commercial applications that demand exact decimal handling, such as currency calculations compliant with regulatory standards.[58][60] Software libraries provide practical implementations of precise decimal arithmetic, often supporting arbitrary precision beyond fixed hardware formats. For example, Python'sdecimal module implements decimal floating-point arithmetic with user-configurable precision (defaulting to 28 significant digits) and rounding modes, ensuring exact representations for decimals like 0.1 and correct results for operations such as 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.3, while signaling inexact results when they occur; it draws from IEEE 754 decimal formats for interoperability. Alternative solutions include fixed-point arithmetic, where numbers are scaled by a fixed power of 10 (e.g., storing cents as integers for dollar amounts) to preserve exact decimal fractions without floating exponents, though this requires manual scaling and is limited by integer overflow risks.[61][62]

![{\displaystyle \left\vert \left[x\right]_{n}-\left[x\right]_{n-1}\right\vert =d_{n}\cdot 10^{-n}<10^{-n+1}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fa97ac58d939553b57b29422c01a1925a436028e)

![{\textstyle \;x=\lim _{n\rightarrow \infty }[x]_{n}\;}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4726bcc43d70340455e0f0340fa72d52ee7e420d)

![{\textstyle \;([x]_{n})_{n=1}^{\infty }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b1ebb69f79147f59b60a7fc1079add44c50c1331)