Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

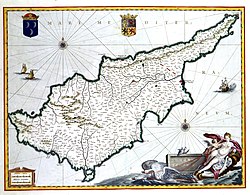

British Cyprus

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2025) |

British Cyprus (Greek: Βρετανική Κύπρος; Turkish: Britanya Kıbrısı) was the island of Cyprus under the dominion of the British Empire, administered sequentially from 1878 to 1914 as a British protectorate, from 1914 to 1925 as a unilaterally annexed military occupation, and from 1925 to 1960 as a Crown colony. Following the London and Zürich Agreements of 19 February 1959, Cyprus became an independent republic on 16 August 1960.

Key Information

History

[edit]

Formation

[edit]Cyprus was a territory of the Ottoman Empire, lastly as part of the Vilayet of the Archipelago, since it was conquered from the Republic of Venice in 1570–71.

A British protectorate under nominal Ottoman suzerainty was established over Cyprus by the Cyprus Convention of 4 June 1878, following the Russo-Turkish War, in exchange for British support of the Ottomans during the Congress of Berlin.[3] Cyprus was then proclaimed a British protectorate and was informally integrated into the British Empire. This remained in place until 5 November 1914, when after the Ottomans joined the Central Powers, in turn entering World War I, Britain declared the complete annexation of Cyprus into the British Empire, albeit under a military administration status. The Crown Colony of Cyprus was proclaimed a decade later, in 1925, after Britain's annexation of Cyprus was verified twice, firstly in the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, which was never implemented, and then confirmed again in the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.[4]

Proposed union with Greece

[edit]King Pávlos of the Hellenes declared that Cyprus desired union with the Kingdom of Greece in 1948. A referendum was presented by the Orthodox Church of Cyprus in 1950, according to which around 97% of the Greek Cypriot population wanted the union. The Greek petition and enosis became an international issue when it was accepted by the United Nations (UN).

Cyprus Emergency

[edit]The Cyprus Emergency was a military action that took place in Cyprus from 1955 to 1959. The Cyprus Emergency primarily consisted of a campaign by the Greek Cypriot military group EOKA to remove the British from Cyprus so it could be unified with Greece.

Independence

[edit]| History of Cyprus |

|---|

|

|

|

Signed on 19 February 1959, the London and Zurich Agreements started the process for the constitution of an independent Cyprus. The United Kingdom granted independence to Cyprus on 16 August 1960 and formed the Republic of Cyprus. Archbishop Makarios III, a charismatic religious and political leader, was elected as the first president of independent Cyprus. As part of the independence agreement, the United Kingdom retained possession of the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia as a British Overseas Territory.

In March 1961 at the 1961 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference, Cyprus became an independent republic in the Commonwealth of Nations, and Archbishop Makarios III became both a Commonwealth head of state and a Commonwealth head of government.

In 1961, the Republic of Cyprus became the 99th member of the United Nations.

Notable residents

[edit]- Fred Harrison (born 1944), British author and economist, was born in British Cyprus.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ as High Commissioner

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The British Empire in 1924". The British Empire. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Cyprus Population". Worldometers. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ Solsten, Eric. (ed.) Cyprus: A country study (1991).

- ^ Xypolia, Ilia (2017). British Imperialism and Turkish Nationalism in Cyprus, 1923–1939 Divide, Define and Rule. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138221291.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cyprus under British rule at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cyprus under British rule at Wikimedia Commons- British Rule in Cyprus (1878–1960) – cypnet.co.uk

.svg/250px-Flag_of_Cyprus_(1922–1960).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Flag_of_Cyprus_(1922–1960).svg.png)