Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Malayan Union

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

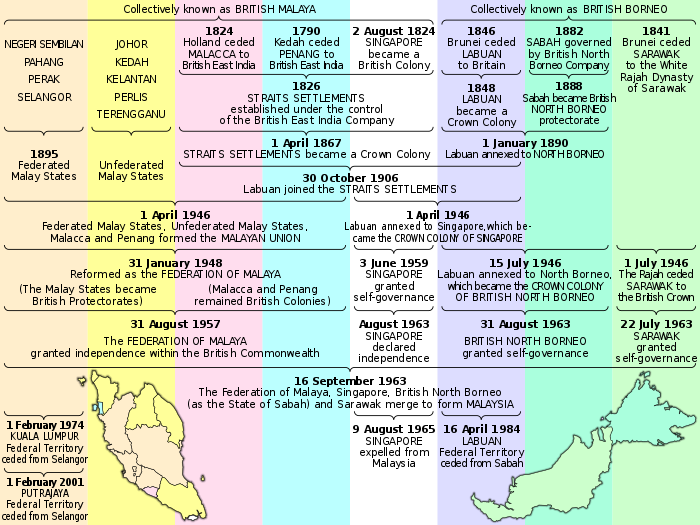

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

The Malayan Union (Malay: Kesatuan Malaya;[1] Jawi: كساتوان مالايا) was a union of the Malay states and the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca. It was the successor to British Malaya and was conceived to unify the Malay Peninsula under a single government to simplify administration. Following opposition by the ethnic Malays, the union was reorganised as the Federation of Malaya in 1948.

Formation of the Malayan Union

[edit]Prior to World War II, British Malaya consisted of three groups of polities: the protectorate of the Federated Malay States, five protected Unfederated Malay States and the crown colony of the Straits Settlements.

On 1 April 1946, the Malayan Union officially came into existence with Sir Edward Gent as its governor, combining the Federated Malay States, Unfederated Malay States and the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca under one administration. The capital of the Union was Kuala Lumpur. The former Straits Settlement of Singapore was administered as a separate crown colony.

The idea of the Union was first expressed by the British in October 1945 (plans had been presented to the War Cabinet as early as May 1944)[1] in the aftermath of the Second World War by the British Military Administration. Sir Harold MacMichael was assigned the task of gathering the Malay state rulers' approval for the Malayan Union in the same month. In a short period of time, he managed to obtain all the Malay rulers' approval. The reasons for their agreement, despite the loss of political power that it entailed for the Malay rulers, has been much debated; the consensus appears to be that the main reasons were that as the Malay rulers were resident during the Japanese occupation, they were open to the accusation of collaboration, and that they were threatened with dethronement.[2] Hence the approval was given, though it was with utmost reluctance.

When it was unveiled, the Malayan Union gave equal rights to people who wished to apply for citizenship. It was automatically granted to people who were born in any state in British Malaya or Singapore and were living there before 15 February 1942, born outside British Malaya or the Straits Settlements only if their fathers were citizens of the Malayan Union and those who reached 18 years old and who had lived in British Malaya or Singapore "10 out of 15 years before 15 February 1942". The group of people eligible for application of citizenship had to live in Singapore or British Malaya "for 5 out of 8 years preceding the application", had to be of good character, understand and speak the English or Malay language and "had to take an oath of allegiance to the Malayan Union". However, the citizenship proposal was never actually implemented. Due to opposition to the citizenship proposal, it was postponed then modified, which made it harder for many Chinese and Indian residents to obtain Malayan citizenship.[3]

The Sultans, the traditional rulers of the Malay states, conceded all their powers to the British Crown except in religious matters. The Malayan Union was placed under the jurisdiction of a British Governor, signalling the formal inauguration of British colonial rule in the Malay peninsula. Moreover, while the State Councils were still kept functioning in the former Federated Malay States, they lost the limited autonomy that they enjoyed, left to administer only some less important local aspects of government, and became an extended hand of the Federal government in Kuala Lumpur. Also, British Residents replacing the Sultans as the head of the State Councils meant that the political status of the Sultans was greatly reduced.[4]

A Supreme Court was established in 1946 of which Harold Curwen Willan was the only Chief Justice.[5]

Opposition, dissolution of the Malayan Union and the creation of the Federation of Malaya

[edit]

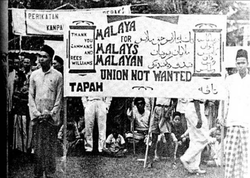

The Malays generally opposed the creation of the Union. The opposition was due to the methods Sir Harold MacMichael used to acquire the Sultans' approval, the reduction of the Sultans' powers, and easy granting of citizenship to immigrants.[6] The United Malays National Organisation or UMNO, a Malay political association formed by Dato' Onn bin Ja'afar on 10 May 1946, led the opposition against the Malayan Union.[7] Malays also wore white bands around their heads, signifying their mourning for the loss of the Sultans' political rights.

After the inauguration of the Malayan Union, the Malays, under UMNO, continued opposing the Malayan Union. They used civil disobedience as a means of protest by refusing to attend the installation ceremonies of the British governors.[6] They also refused to participate in the meetings of the Advisory Councils. The British recognised this problem and took measures to consider the opinions of the major races in Malaya before making amendments to the constitution. The Malayan Union was dissolved and replaced by the Federation of Malaya on 1 February 1948.[7]

List of member states

[edit]Evolution towards Malaysia

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]1. ^ Rarely used; often referred by its English name Malayan Union in textbooks and official material.

References

[edit]- ^ CAB 66/50 'Policy in Regard to Malaya and Borneo'

- ^ Ariffin Omar, Bangsa Melayu: Malay Concepts of Democracy and Community, 1945–1950 (Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 46. Cited in Ken'ichi Goto, Tensions of Empire: Japan and Southeast Asia in the Colonial and Postcolonial World (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2003), p. 222

- ^ Carnell, Malayan Citizenship Legislation, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 1952

- ^ Lee Kam Hing. "Road to Independence (1): Birth of Umno and Malayan Union". CPI. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Ming Ho, Tak. Generations: The Story of Batu Gajah. p. 165.

- ^ a b Lapping, Brian (1985). End of empire. Internet Archive. New York : St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-25071-3.

- ^ a b "History of Malaysia – The impact of British rule | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 May 2025.

- Zakaria Haji Ahmad. Government and Politics (1940–2006). p.p 30–21. ISBN 981-3018-55-0.

- Marissa Champion. Odyssey: Perspectives on Southeast Asia – Malaysia and Singapore 1870–1971. ISBN 9971-0-7213-0

- Sejarah Malaysia [2]

Malayan Union

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context

Pre-War Colonial Administration

Prior to the Japanese invasion in December 1941, British colonial governance in Malaya operated through a decentralized structure comprising the Straits Settlements, the Federated Malay States, and the Unfederated Malay States, reflecting a policy of indirect rule in the peninsula's interior while exerting direct control in coastal trading hubs.[11] The Straits Settlements—Penang (established 1786), Singapore (1819), and Malacca—functioned as crown colonies under a governor based in Singapore after 1833, with administrative separation from India in 1867 placing them directly under the Colonial Office.[12] Governance featured executive and legislative councils dominated by British officials, though limited elected representation for European, Chinese, and Indian communities was introduced in the Legislative Council by the 1920s, totaling 12 unofficial members by 1933 alongside appointed officials.[13] The Federated Malay States (FMS), formed in 1895 through treaties with the sultans of Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, and Pahang, embodied indirect rule: British Residents advised rulers on administration, finance, and policy—excluding Islam and Malay customs—while a Resident-General in Kuala Lumpur coordinated federal functions such as railways, police, and land revenue, amassing over 80% of Malaya's tin and rubber output by the 1930s.[14][15] This federation centralized infrastructure and economic extraction but preserved nominal Malay sovereignty, with the High Commissioner overseeing all territories from the FMS capital. In the Unfederated Malay States—Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu—British influence was lighter, mediated by individual Advisers appointed from the 1900s onward, allowing rulers greater leeway in internal affairs amid ongoing treaty negotiations, such as Kedah's cession of sovereignty in 1909.[11] Malaya's pre-war economy centered on export commodities, with tin mining—yielding 30% of global supply by 1937—reliant on Chinese migrant labor organized through secretive kongsi networks, and rubber plantations, which expanded to 3.5 million acres by 1938, drawing over 600,000 Indian workers under indenture-like systems prone to exploitation and debt bondage.[16][17] Malays, comprising about 50% of the 4.4 million population in 1931, largely remained in subsistence rice farming and avoided wage labor, benefiting from land reservations and exemptions from income tax not extended to immigrants.[18] No overarching citizenship framework existed; Malays in the FMS and Unfederated States held subject status under their sultans as protected indigenous persons with customary privileges, while Straits-born residents of any ethnicity could claim British subjecthood, though non-Europeans faced de facto discrimination in civil service and land rights.[19]Japanese Occupation and Its Aftermath

The Japanese invasion of Malaya began on 8 December 1941, with the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, leading to the establishment of military administration under the banner of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which promised Asian liberation from Western colonialism but prioritized resource extraction for Japan's war effort.[20] Japanese firms seized control of plantations, mines, and industries, while introducing the military yen that fueled hyperinflation and absorbed surplus labor into forced projects by late 1943.[21] Rice imports, which supplied two-thirds of pre-war needs, were curtailed, prompting rationing, black markets, and a shift to subsistence crops like tapioca and sweet potatoes; this resulted in widespread malnutrition and elevated death rates during the 1943–1944 shortages.[21] Malay sultans were initially retained as nominal figureheads to secure local cooperation, with their religious authority respected to appeal to Muslim Malays, but their political power was systematically eroded by mid-1942 through coerced transfers of sovereignty in exchange for stipends and honors, such as the 48,000 yen paid to the Sultan of Johore by May 1942.[22] Some rulers collaborated, including radio appeals for support from Kedah's leadership in December 1941, which undermined their pre-war legitimacy amid perceptions of subservience to the occupiers.[22] Ethnic policies exacerbated divisions: Malays were initially positioned as equals in the anti-colonial narrative, while Chinese communities faced brutal purges like the Sook Ching operation in February–March 1942, with Japanese reports claiming 6,000 executions in Singapore alone and postwar estimates ranging up to 50,000 across Malaya due to suspected anti-Japanese sympathies.[23] Later Kempeitai repressions targeted resistors across groups, intensifying inter-ethnic mistrust that persisted beyond the occupation.[24] Japan's surrender on 15 August 1945 created a power vacuum filled temporarily by the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), a predominantly Chinese communist guerrilla force that seized territory, executed suspected collaborators, and administered justice in rural areas until British forces arrived.[25] The British Military Administration (BMA), established in September 1945, inherited an economy in collapse with ongoing hyperinflation, disrupted supply chains, and persistent food deficits, compounded by ineffective policing and illicit arms circulation.[26] Labor unrest surged, including general strikes led by communist-influenced unions—such as the February 1946 action marking Singapore's fall—demanding wage hikes amid rising costs, while MPAJA remnants fostered anti-colonial agitation among Chinese squatters and workers.[26] These conditions, alongside Malay anxieties over Chinese dominance and weakened sultanate prestige, amplified calls for administrative overhaul to restore order and address emerging nationalist sentiments.[3]British Post-War Reforms

Planning and Proposals

The British planning for post-war Malaya commenced in mid-1943 with the establishment of the Malayan Planning Unit by the Colonial Office and War Office, tasked with devising administrative reforms to address fragmented pre-war structures and facilitate economic recovery after Japanese occupation.[27] Internal deliberations, primarily within the Colonial Office's Eastern Department, accelerated that year in response to wartime strategic needs, emphasizing a unified administrative framework to streamline governance across the Malay states, Penang, and Malacca while excluding Singapore as a separate entity.[8] These proposals prioritized centralized control under a British Governor with executive powers, including authority over defense, external affairs, and internal security, supported by an appointed legislative council.[28] In August 1945, following Japan's surrender, the Colonial Office appointed Sir Harold MacMichael, formerly High Commissioner for Palestine, to secure legal basis for the scheme through new treaties with the nine Malay sultans.[29] MacMichael's mission, conducted between late August and early October 1945, involved rapid negotiations where sultans were pressed to cede sovereignty to the British Crown, retaining only ceremonial roles and advisory influence on Malay customs and Islam; the British leveraged recognition of rulers' legitimacy post-occupation as implicit pressure.[2] By October 11, 1945, MacMichael reported all sultans had signed, enabling the union's constitutional foundation, though the process's haste and secrecy later fueled accusations of duress.[8] The Malayan Union scheme was formally outlined in a White Paper (Cmd. 6724) published on January 22, 1946, proposing a welfare-infused administration with universal citizenship granted by birth in Malaya, parental origin, or long-term residence to integrate the predominantly immigrant Chinese and Indian populations into a multi-ethnic polity.[30] British rationale centered on efficiency gains from eliminating dual governance systems, promoting rubber and tin export recovery, and introducing social services like health and education under centralized funding, viewing traditional Malay state autonomies as obsolete barriers to modernization.[28] Planners in London, drawing on liberal democratic principles, dismissed potential Malay resistance as parochial, assuming economic benefits and inclusive citizenship would secure acquiescence without broad consultation.[8]Objectives and British Rationale

The British government, through the Colonial Office, sought to centralize authority in Malaya following the Japanese occupation's administrative chaos, proposing the Malayan Union on October 17, 1945, to consolidate the Federated Malay States, Unfederated Malay States, Penang, and Malacca under a single governor, thereby eliminating overlapping jurisdictions and reducing bureaucratic redundancies that had hampered pre-war governance.[3] This streamlining was intended to facilitate rapid post-war reconstruction, including infrastructure repair and resource mobilization, as the fragmented state system was deemed inefficient for coordinating emergency measures and long-term planning.[1] The rationale emphasized practical imperial reconfiguration amid Britain's depleted resources after World War II, prioritizing unified command to restore order without relying on disparate local rulers' capacities. A core objective involved extending citizenship to non-Malay immigrants, particularly Chinese and Indian laborers who comprised a significant portion of the workforce in tin mining and rubber plantations, to cultivate loyalty to the colonial administration and mitigate risks from communist agitation among these groups, who lacked ties to traditional Malay sultanates.[8] Economically, the Union aimed to stabilize labor supplies and attract British and international investment by presenting a cohesive territory with standardized policies, viewing the pre-existing divisions as obstacles to efficient extraction and export of Malaya's primary commodities, which had generated substantial revenue before 1942.[1] This approach reflected an implicit assumption that economic imperatives would override ethnic particularisms, with the plan projecting enhanced productivity through centralized fiscal controls and development funds. Under the Attlee Labour government, the proposal marked an ideological departure from pre-war indirect rule, which had preserved Malay rulers' privileges and restricted non-Malay rights, toward a more direct, unitary model influenced by domestic emphases on social welfare and modernization, though adapted to colonial needs for security and revenue.[8] British planners, including figures like Malcolm MacDonald, anticipated that inclusive citizenship and uniform administration would foster a multi-racial polity aligned with imperial interests, potentially countering both separatist tendencies and leftist threats without anticipating the depth of indigenous attachment to federal structures and sultanic authority.[8] This oversight prioritized immediate administrative and economic consolidation over sustained ethnic equilibrium, assuming short-term centralization would yield enduring stability.Establishment and Governance

Proclamation and Initial Implementation

The Malayan Union was formally established on 1 April 1946, with Sir Edward Gent appointed as its first Governor and the administrative territories of the nine Malay states, Penang, and Malacca unified under centralized British authority.[31][2] Prior to the launch, treaties had been concluded between the British Crown and the nine Malay rulers—covering Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Selangor, and Terengganu—transferring their executive and legislative powers to the Governor, while retaining only nominal religious and customary roles for the sultans.[7] The inauguration ceremony in Kuala Lumpur was boycotted by the Malay rulers, signaling early discord, though Gent proceeded to assume control amid a framework that dissolved pre-existing state councils and replaced them with advisory bodies where sultans held ceremonial influence without substantive authority.[2][32] Implementation encountered prompt operational hurdles, including resistance from entrenched bureaucratic elements accustomed to decentralized colonial structures, which slowed the integration of disparate administrative systems. Economic strains intensified through widespread labor unrest, as strikes across industries resulted in approximately 713,000 man-days lost in the ensuing year, equivalent to nearly two days per employee and disrupting tin mining, rubber plantations, and port operations critical to post-war recovery.[33] These disruptions compounded supply shortages and inflation inherited from the Japanese occupation, testing the Union's capacity for cohesive governance.[34] Among non-Malays, particularly Chinese and Indian communities comprising over half the population, there was tentative initial acceptance of the Union due to its provisions for broad citizenship eligibility based on residency and loyalty oaths, which promised equal political rights and economic participation absent under prior fragmented administrations.[8][35] This contrasted with Malay elite grievances but underscored the scheme's appeal to immigrant-descended groups seeking formalized status, though practical rollout faced delays in registration and verification processes.[9] Overall, these early dynamics exposed flaws in rapid centralization, paving the way for escalating challenges that curtailed the Union's viability to under two years before its replacement by the Federation of Malaya in February 1948.[31]Administrative Structure

The Malayan Union implemented a highly centralized administrative system under a single British Governor, who exercised supreme executive, legislative, and judicial authority over the entire territory, encompassing the nine Malay states and the settlements of Penang and Malacca. Sir Edward Gent was appointed as the inaugural Governor, assuming office on 1 April 1946. This structure vested all key powers—including finance, defense, internal security, and foreign relations—in the central government based in Kuala Lumpur, markedly differing from the pre-war decentralized arrangement of semi-autonomous states under Residents or Advisers and a separate Straits Settlements administration.[9][36] Governance operated through a classic colonial hierarchy: the Governor, supported by an appointed Executive Council for policy advice and a Legislative Council for enacting laws, both dominated by British officials with overriding gubernatorial veto power. The Legislative Council initially comprised approximately 22 official members (including departmental heads) and 21 unofficial nominees, selected by the Governor without public elections or proportional communal representation. Traditional Malay state councils were demoted to advisory roles, with executive functions transferred to centrally appointed State Secretaries, effectively sidelining local autonomy.[36][37] Administratively, the Union divided the peninsula into states and settlements, subdivided into districts overseen by British District Officers responsible for local implementation of central directives, such as revenue collection and law enforcement. This bypassed pre-war intermediaries like state executives, aiming for streamlined control but imposing uniform policies across varied rural and urban terrains, from coastal settlements to inland highlands. Sultans retained ceremonial titles and formed a consultative Council of Rulers, yet lacked veto or substantive decision-making powers, rendering them figureheads in the new framework.[36][38]Citizenship Provisions and Legal Framework

The citizenship provisions of the Malayan Union were enshrined in the Malayan Union Order in Council, promulgated on 1 April 1946, which established a uniform status applicable across the nine Malay states and the Settlements of Penang and Malacca.[39] This framework marked a departure from pre-war colonial distinctions, where Malays were subjects of their rulers and non-Malays held varying degrees of British subject status or foreign nationality, by introducing a civic-based model prioritizing birthplace and residency over ethnic or ascriptive ties.[40] The Order aimed to foster a singular Malayan identity through equal legal entitlements, including access to public services, voting in local elections, and land ownership rights, for those meeting the criteria.[41] Eligibility for automatic citizenship extended jus soli principles to all individuals born within the Union's territory after its establishment, irrespective of parental origin, thereby encompassing children of Chinese, Indian, and other immigrant communities alongside Malays.[41] Naturalization was available to those ordinarily resident in Malaya for a qualifying period—typically five years out of the preceding ten—subject to an oath of allegiance to the British Crown and the Union, as well as payment of a nominal registration fee.[39] These criteria applied without ethnic qualifications, potentially granting status to approximately 2.5 million non-Malays out of a total population of around 4.9 million in 1947, many of whom dominated urban commerce and formed a numerical plurality in key economic sectors.[40] The legal framework integrated citizenship with governance by linking it to participation in the Union's Legislative and Executive Councils, where only citizens could hold certain offices or vote in restricted elections, though initial implementation saw limited registrations among non-Malays due to the oath requirement and administrative hurdles.[42] This structure implied a shift toward demographic proportionality in political influence and resource allocation, as non-citizen status previously confined many immigrants to transient labor roles without equivalent claims to territory or sovereignty.[41] The provisions were revoked in 1948 upon the Union's dissolution, replaced by the more restrictive Federation of Malaya citizenship under the 1948 Order in Council, which reintroduced ethnic preferences for Malays.[43]Opposition and Resistance

Reactions from Malay Rulers

The Malay rulers signed treaties with Sir Harold MacMichael between 20 October and 21 December 1945, formally ceding sovereignty over their states to the British Crown and revoking pre-war protections that had preserved their autonomy in internal affairs.[44][45] These agreements were concluded amid post-occupation instability, with rulers facing implicit threats of dethronement for perceived Japanese collaboration, rendering the process coercive and lacking genuine consent.[46][7] In response, the rulers repudiated the treaties' legitimacy, declaring them invalid due to duress and incompatibility with longstanding pacts like the 1874 Pangkor Treaty, which had established advisory roles for British residents while upholding sultanic authority in Perak and influencing similar arrangements elsewhere.[7][47] The Sultan of Perak explicitly protested the Union on 5 February 1946, highlighting the erosion of traditional governance structures.[3] Appeals invoked the rulers' roles as defenders of Islam and Malay adat, positioning the Union as a direct assault on their custodianship over cultural and religious sovereignty, absent from pre-war colonial compacts.[48] Sultan Ibrahim of Johor emerged as a leading voice in defiance, with Johor signing first yet spearheading resistance by refusing formal recognition of the Union's governor, Sir Edward Gent.[45] The rulers collectively boycotted Gent's installation on 1 April 1946, signaling unified rejection of the centralized authority that subordinated their historic prerogatives to a unitary British administration.[49][50] This stance underscored their perception of the Union as colonial overreach, prioritizing administrative efficiency over the federated balance that had maintained Malay political identity.[3]Emergence of Malay Nationalism

The threat posed by the Malayan Union scheme, which proposed centralizing authority and extending citizenship to non-Malays, galvanized pre-existing Malay elite sentiments toward unified political action, transforming latent ideas of kesatuan Melayu—emphasizing Malay unity and primacy—into organized resistance. Pre-war associations, such as the Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) formed in 1938, had laid intellectual foundations by advocating for Malay solidarity amid economic marginalization and colonial policies favoring immigrant communities, though these efforts remained fragmented and often suppressed during the Japanese occupation.[51][52] The Union's provisions, including diminished sovereignty for Malay rulers and demographic shifts diluting Malay political dominance, amplified these concepts, prompting elites to prioritize the preservation of bangsa Melayu identity and traditional state structures over passive deference to British administration.[53] In March 1946, the Pan-Malayan Malay Congress convened in Kuala Lumpur, uniting representatives from over 40 Malay organizations to articulate demands for restoring pre-war state autonomies and rejecting the Union's centralization.[47] This gathering marked a pivotal coalescence of disparate regional associations, shifting Malay elites from episodic petitions to a coordinated front emphasizing ketuanan Melayu—Malay overlordship—as essential to countering existential threats to land rights, cultural hegemony, and monarchical legitimacy. The congress's resolutions underscored a causal link between British reforms and the erosion of Malay privileges, framing opposition as a defense of historical entitlements rather than mere reactionism.[51] This momentum culminated in the formation of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) on May 11, 1946, at an annual general meeting in Johor Bahru's Istana Besar, with Dato' Onn bin Jaafar elected as its inaugural president.[53] UMNO consolidated the congress's elite networks into a national entity, explicitly tasked with opposing the Union while fostering assertive Malay nationalism that prioritized ethnic self-preservation and state rights restoration. By institutionalizing these efforts, it represented a departure from pre-war parochialism, channeling ruler-elite alliances into a modern political vehicle that viewed the Union as a catalyst for broader independence aspirations grounded in Malay-centric governance.[54]Grassroots Protests and Organizations

Grassroots opposition to the Malayan Union intensified through mass demonstrations, petitions, and organized gatherings across Malay states in 1946. Local Malay associations coordinated protests, including public marches where participants voiced concerns over the erosion of Malay sovereignty and special rights. These actions amplified elite-led resistance by mobilizing ordinary Malays, with events such as the first All-Malay Congress in March 1946 uniting 41 organizations to demand rejection of the Union.[45][9] Religious leaders, particularly ulama from the Kaum Tua tradition, played a pivotal role by framing the protests as a defense of Islamic principles and Malay adat against centralization that threatened religious authority. Their involvement lent moral and communal legitimacy, encouraging participation in non-violent actions like boycotts and public rallies. Ulama-led gatherings emphasized the Union's potential to undermine sultanates' roles as protectors of Islam, galvanizing rural and urban communities.[55][56] Women and youth expanded the movement's base, with Malay women defying traditional seclusion to join marches and carry placards, while emerging youth groups within broader nationalist networks contributed to sustained mobilization. This grassroots engagement sustained pressure through 1946-1947, contributing causally to British policy reversal by demonstrating widespread Malay unity and non-compliance risks. The non-violent tactics, avoiding escalation to violence, highlighted empirical effectiveness in forcing concessions without alienating potential allies.[9][9]Controversies and Criticisms

Ethnic and Demographic Concerns

The Malayan Union's proposed citizenship framework, which extended automatic rights to all individuals born within the territory irrespective of ethnic origin or parental allegiance, intensified fears among Malays that their narrow demographic majority would be politically overwhelmed by non-Malay groups. The 1947 census recorded Peninsular Malaya's population at approximately 4.9 million, with Malays comprising about 50%, Chinese around 38%, and Indians roughly 10%.[57] These proportions underscored Malay apprehensions that universal suffrage under centralized governance would enable economically ascendant immigrant communities—predominantly Chinese merchants and Indian laborers—to dominate elections, land policies, and resource allocation, eroding indigenous Malay claims rooted in historical residency and customary law.[3] Such concerns reflected a pragmatic recognition of integration challenges: many Chinese maintained extraterritorial loyalties to China, exemplified by their overrepresentation in the Malayan Communist Party, which launched insurgencies shortly after the Union's formation, while Indians often retained ties to British India.[58] Malay elites argued that equating recent arrivals with natives ignored settlement patterns, where non-Malays clustered in urban enclaves and plantations with minimal assimilation into rural Malay society, potentially leading to governance capture without reciprocal cultural or security commitments. Non-Malay responses to these provisions were generally muted, with Chinese and Indian associations largely welcoming the citizenship expansions as avenues for legal equality and property rights, though some Peranakan Chinese voiced caution over escalating interethnic tensions from Malay boycotts and protests.[59] This asymmetry highlighted the policy's oversight of loyalty disparities, prioritizing abstract equity over verifiable stakes in Malaya's sovereignty.[8]Debates on Sovereignty and Centralization

The British colonial administration proposed the Malayan Union in 1946 as a centralized entity that would transfer sovereignty from the nine Malay sultans to the British Crown, reducing the rulers to ceremonial roles focused on Islam and Malay customs while establishing a single governor with broad executive powers.[3] This structure aimed to consolidate the fragmented pre-war system of Federated and Unfederated Malay States plus Penang and Malacca, enabling streamlined decision-making for post-Japanese occupation recovery.[8] Proponents within the Colonial Office argued that centralization would enhance administrative efficiency by eliminating overlapping state-level bureaucracies, facilitating uniform economic policies for key industries like rubber and tin, and promoting coordinated welfare initiatives such as education and health services across the peninsula.[3] These measures were presented as pragmatic responses to wartime disruptions, where decentralized authority had hindered rapid reconstruction; for instance, the plan envisioned a central legislature to enact consistent laws, ostensibly modernizing governance beyond what the sultans' advisory roles under 19th-century treaties had allowed.[8] However, such arguments rested on a legalistic interpretation of the 1945 MacMichael Treaties, hastily negotiated between October and December amid post-surrender instability, which the British viewed as superseding earlier pacts like the 1874 Pangkor Treaty for Perak or similar agreements that preserved sultans' sovereignty while granting British "advice" on administration.[3] Opponents, including Malay elites and emerging nationalists, contended that the scheme violated the spirit of those historical treaties, which positioned sultans as sovereign anchors of Malay identity and social stability rather than mere figureheads.[44] They emphasized that sultans embodied customary legitimacy (adat) intertwined with religious authority, serving as causal bulwarks against fragmentation; eroding their powers risked destabilizing Malay society by severing ties to pre-colonial traditions that had endured British indirect rule.[8] This perspective highlighted a British miscalculation in prioritizing imposed legal reforms over entrenched cultural norms, where sultans' roles extended beyond symbolism to mediating community cohesion in a multi-ethnic context.[3] Empirically, the centralization effort faltered within months of the Union's April 1, 1946, proclamation, as sultan boycotts and widespread non-cooperation exposed cultural mismatches between top-down efficiency drives and local reliance on ruler-mediated legitimacy.[8] While the plan introduced some paternalistic welfare provisions, such as centralized land and labor reforms intended for equitable development, these were critiqued as overreaching impositions that disregarded sultans' traditional oversight, ultimately necessitating reversal by February 1948 in favor of the Federation of Malaya to restore state autonomies.[3] The episode underscored the causal primacy of customary institutions in maintaining order, as legal fiat alone proved insufficient against rooted opposition.[8]Non-Malay Perspectives and Limited Support

The Chinese community in Malaya exhibited limited engagement with the Malayan Union proposal, prioritizing post-war economic recovery over political reorganization. Many Chinese, particularly recent immigrants, maintained strong ties to China and viewed Malaya primarily as an economic base rather than a homeland, leading to widespread apathy toward the citizenship provisions despite their potential to grant equal rights based on residence.[60] Chambers of commerce, representing business interests, pragmatically accepted the citizenship framework for its promise of legal security for investments and property, but refrained from active endorsement amid fears of alienating British authorities essential for trade restoration.[61] The Malayan Communist Party (MCP), influential among segments of the Chinese working class, displayed ambivalence, critiquing the Union as insufficiently radical for proletarian control while exploiting labor unrest for broader anti-colonial aims rather than focusing on its constitutional aspects.[62] Indian perspectives were similarly divided, with pragmatic support for equality provisions tempered by internal cleavages and loyalty to British imperial structures. A majority within the Indian community favored the Union's jus soli citizenship model, which would formalize residency rights for laborers and traders displaced by wartime disruptions, aligning with demands for non-discriminatory access to land and services.[63] However, the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC), formed in August 1946, opposed the Union despite these benefits, reflecting leadership concerns over centralized authority diminishing communal representation and potential backlash from Malay elites.[60] Splits arose from divided allegiances—some Indians prioritized ties to independent India, others sought accommodation with Britain for economic patronage—resulting in minimal organized advocacy.[64] Overall, non-Malay mobilization remained negligible, as communities focused on rebuilding livelihoods amid inflation and supply shortages following Japanese occupation, rather than contesting the Union's form. This apathy stemmed from causal factors including extraterritorial loyalties, economic dependence on British reconstruction, and recognition that demographic concentrations in urban-rural enclaves necessitated stable protections over risky political advocacy.[65] Unlike Malay resistance rooted in existential threats to sovereignty, non-Malays perceived aligned incentives with British administration for commerce and residency security, limiting support to passive acceptance without grassroots campaigns.[62]Dissolution and Transition

Negotiations and Policy Reversal

The British authorities, confronted with unified opposition from the Malay rulers and the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), established a Working Committee in October 1946 to revise the Malayan Union's constitutional framework.[53] The committee included representatives from the British government, the nine Malay sultans, and UMNO leaders such as Dato Onn bin Jaafar, focusing on restoring the rulers' traditional sovereignty over Malay states and Malay reservations while addressing citizenship provisions.[60] These deliberations reflected Britain's pragmatic assessment that enforcing the Union's centralization amid boycotts and petitions risked escalating administrative costs and post-war instability, outweighing the anticipated efficiencies of unified governance.[8] The Working Committee's report, released on 24 December 1946, proposed key reversals: reinstating the sultans' authority in internal matters, excluding the Straits Settlements from a peninsular federation, and restricting automatic citizenship to those with demonstrable Malay ties or long-term residency under stricter jus soli criteria.[60] British officials conceded these points after empirical evidence of resistance— including over 100,000 signatures on anti-Union petitions and the rulers' collective abdication threats—demonstrated the scheme's untenability without coercive measures that could undermine colonial legitimacy.[53] The negotiations prioritized causal stability factors, such as averting ethnic polarization and securing Malay cooperation for economic reconstruction, over the original policy's demographic equalization aims. Further conferences in January 1947 between Governor Sir Edward Gent, the rulers, and UMNO refined these concessions, leading to the White Paper on constitutional proposals issued on 5 March 1947.[8] By recognizing the opposition's organizational cohesion—evident in UMNO's rapid mobilization of 400 branches by mid-1946—the British shifted from unilateral imposition to collaborative reform, calculating that adaptation preserved imperial interests more effectively than suppression.[53] The policy reversal culminated in the announcement of the Malayan Union's dissolution effective 1 February 1948, following ratification by the Malay rulers and parliamentary approval in London.[8] This timeline underscored Britain's response to the opposition's demonstrated leverage, as sustained non-cooperation threatened revenue collection and security in a region recovering from Japanese occupation and facing communist insurgency precursors.[66]Creation of the Federation of Malaya

The Federation of Malaya was established effective 1 February 1948, succeeding the Malayan Union via the Federation of Malaya Agreement signed on 21 January 1948 between the British Crown and the nine Malay Rulers.[67][68] This compromise centralized federal administration for economic and security coordination while devolving powers to state level, including restoration of executive authority for the Rulers over Islamic affairs, Malay adat (customs), and land reservations exclusively for Malay use.[69] State councils, comprising Rulers and appointed members, were revived in each Malay state to advise on local matters, reversing the Union's direct British governance model.[70] Provisions enshrined special Malay privileges, designating Malay as the national language, Islam as the religion of the Federation, and according Malays preferential access to public scholarships, civil service positions, and business licenses to counterbalance demographic pressures from non-Malay immigration.[69] Of the approximately five million residents in 1948, around 3.1 million qualified for automatic federal citizenship—predominantly Malays (78 percent of qualifiers)—with the remainder facing barriers.[71] Non-automatic applicants, typically recent Chinese or Indian arrivals, needed 15 years' continuous residence, proficiency in Malay or English, good character certification, and a declaration of permanent intent, imposing de facto tests that limited mass naturalization.[72] Penang and Malacca, formerly Straits Settlements, were integrated as federal territories rather than states, retaining distinct administrative safeguards such as protections for non-Malay land rights and commercial interests to mitigate local secessionist sentiments.[70] The Federation's constitutional framework outlined incremental steps toward self-rule, including municipal elections from 1952 and nationwide polls for the Federal Legislative Council on 27 July 1955, which elected 52 members and paved the way for internal autonomy negotiations.[73]Territories and Membership

Included States and Settlements

The Malayan Union, established on 1 April 1946, encompassed the nine Malay states of Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Selangor, and Terengganu, together with the former Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca.[4][74] These states included both the previously Federated Malay States (Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang) and the Unfederated Malay States (Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, Terengganu). Penang and Malacca, detached from the dissolved Straits Settlements, were integrated as settlements without traditional rulers.[75] Singapore was excluded from the Union and reconstituted as a separate Crown Colony effective 1 April 1946.[74] The Union's territory spanned the Malay Peninsula, featuring geographic diversity from coastal enclaves and northern paddy fields to central highlands and southern ports, supporting varied economies centered on agriculture, mining, and trade.[76] The 1947 census recorded a total population of approximately 4.9 million inhabitants across these territories.[76]Legacy and Impacts

Catalyst for Malay Political Unity

The Malayan Union proposal, outlined in the British White Paper Cmd. 6724 released on 21 January 1946, threatened to diminish the sovereignty of the Malay rulers and extend citizenship rights to non-Malays on equal terms, thereby diluting the special position of the Malay population amid rapid demographic changes from immigration. This existential challenge unified previously fragmented state-level Malay associations, which had operated in isolation, into a coordinated pan-peninsular resistance.[53][9] In response, the Pan-Malayan Malay Congress convened in March 1946, building on earlier rallies such as the February 1946 gathering in Johore that drew 15,000 participants, and directly led to the founding of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) on 11 May 1946 under Dato' Onn bin Jaafar. UMNO orchestrated widespread mobilization, including petitions, mass demonstrations, and boycotts—such as Malay civil servants refusing to perform duties and the sultans absenting themselves from the Union's inauguration on 1 April 1946—transforming elite concerns into a popular movement that engaged grassroots elements like the women's wing Kaum Ibu, which grew to 20,000 members by 1947.[53][9] Far from mere reactionary impulses, the opposition reflected a pragmatic recognition of causal risks to Malay identity and political dominance in a multi-ethnic context, evidenced by UMNO's strategic co-optation of the rulers and negotiation leverage that compelled British concessions through a dedicated Malay delegation led by Dato' Onn in mid-1946. This empirical success in collective bargaining not only reversed the policy but entrenched UMNO as the preeminent Malay political entity, averting fragmentation into rival ethnic factions by channeling disparate loyalties into a singular, enduring structure.[53]Influence on Path to Independence

The opposition to the Malayan Union galvanized Malay elites and masses, prompting the British to replace it with the Federation of Malaya on 1 February 1948, which restored the sovereignty of the nine Malay sultans and restricted automatic citizenship primarily to those of Malay descent or with longstanding residency ties, thereby embedding ethnic safeguards into the federal structure.[77][57] This 1948 framework served as the foundational template for the independent Federation's constitutional monarchy, influencing the Reid Commission's 1956-1957 deliberations by prioritizing federalism with reserved Malay privileges in land, language, and public service to counterbalance non-Malay demographic majorities in urban areas stemming from pre-war immigration.[57] The Union's failure accelerated demands for self-governance, as evidenced by the United Malays National Organisation's (UMNO) post-1946 campaigns, which evolved into the Alliance Party's 1952 coalition with the Malayan Chinese Association and Malayan Indian Congress, securing a landslide in the 1955 federal elections with 51 of 52 seats and prompting London to initiate independence talks.[78] This political consolidation enabled negotiations yielding the 20 February 1956 constitutional blueprint, ratified for Merdeka on 31 August 1957.[78] Central to this trajectory was the citizenship compromise: non-Malays gained pathways to federal citizenship under Article 14 of the 1957 Constitution—via birth, descent, or registration after 10-15 years' residence—while Malays secured Article 153's special rights, including quotas in education and employment, to rectify economic disparities where non-Malays dominated commerce amid Malays' rural poverty.[57] This quid pro quo, forged in the Federation era, preempted ethnic violence by institutionally addressing causal imbalances from colonial labor policies, enabling a negotiated transition absent the civil strife seen in partitioned India or Algeria.[57]Long-Term Effects on Ethnic Policies

The failure of the Malayan Union in 1948, driven by widespread Malay opposition to its provisions for unrestricted citizenship and equal rights for non-indigenous residents, reinforced the principle of safeguarding indigenous primacy in subsequent governance structures. This opposition, led by newly formed groups like UMNO, compelled British authorities to replace the Union with the Federation of Malaya Agreement, which explicitly preserved Malay special privileges in land reservation, public service quotas, and economic protections.[9] These concessions formed the foundational template for ethnic policy frameworks that prioritized demographic stability over unqualified equality, recognizing the numerical majority of Malays (approximately 50% of the population in the 1947 census) alongside the economic dominance of Chinese immigrants.[79] This legacy directly informed Article 153 of the 1957 Federal Constitution, which entrenches the Yang di-Pertuan Agong's duty to protect the special position of Malays and natives of Sabah and Sarawak through quotas in civil service, education, and business permits, while balancing interests of other communities. The article's origins trace to post-Union negotiations under the Reid Commission, where Malay leaders insisted on formal protections to avert marginalization amid rapid urbanization and immigrant labor influxes that had already skewed economic control—Malays held under 2% of corporate equity pre-independence.[80] Article 153's entrenchment, requiring two-thirds parliamentary approval and sultans' consent for amendments, underscores a deliberate long-term commitment to these arrangements as a causal mechanism for federal cohesion in a multi-ethnic state.[81] Subsequent expansions, such as the 1971 New Economic Policy (NEP), built on this framework by institutionalizing Bumiputera preferences to restructure society, targeting 30% Malay ownership in enterprises and poverty eradication irrespective of race, but with explicit ethnic quotas to address post-colonial disparities. Empirical data post-NEP implementation show Bumiputera household incomes growing at the highest rate among ethnic groups from 1970 to 2019, lifting Malay poverty from 49% in 1970 to under 1% by 2020, while averting escalation of tensions seen in the 1969 riots that killed over 140.[82] Critics argue these policies have entrenched ethnic silos and fostered dependency, with non-Bumiputera groups facing barriers in public sector employment (over 80% reserved) and university admissions, potentially hindering merit-based integration.[83] Yet, causal analysis reveals they empirically forestalled Yugoslavia-like fragmentation in a polity with comparable ethnic pluralism and historical grievances, by aligning policy with demographic realities rather than abstract egalitarianism—Malaysia's GDP per capita rose from $1,000 in 1970 to $11,000 by 2020 without state collapse.[84] In contemporary Malaysia, Union-era precedents continue shaping debates on federalism and affirmative action, with calls for needs-based reforms clashing against entrenched safeguards; for instance, the 2021 Shared Prosperity Vision 2030 proposed diluting quotas but retained Bumiputera targets amid fears of renewed polarization. This persistence reflects a realist acknowledgment that assimilationist pressures on indigenous majorities risk backlash, as evidenced by sustained UMNO dominance in coalitions prioritizing ethnic balance over universalism.[85]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cabinet_Memorandum._Policy_in_regard_to_Malaya_and_Borneo._Memorandum_by_the_Secretary_of_State_for_the_Colonies._29_August_1945

.svg/250px-Flag_of_Malaya_(1896–1950).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Flag_of_Malaya_(1896–1950).svg.png)