Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cyprus problem

View on Wikipedia

| Cyprus problem | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Flag map showing the current division, with territory controlled by the internationally-recognised Cyprus and Turkish-backed Northern Cyprus separated by the UN buffer zone. UK bases (Akrotiri and Dhekelia) are also depicted. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Supported by: (with international community recognition) |

|

Supported by: | ||||||

| Part of a series on the Cyprus dispute |

| Cyprus peace process |

|---|

|

|

|---|

The Cyprus problem, also known as the Cyprus conflict, Cyprus issue, Cyprus dispute, or Cyprus question, is an ongoing dispute between the Greek Cypriot and the Turkish Cypriot community in the north of the island of Cyprus, where troops of the Republic of Turkey are deployed. This dispute is an example of a protracted social conflict. The Cyprus dispute began after the Greek Cypriot community challenged the British occupation of the island in 1955, the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état executed by the Cypriot National Guard and sponsored by the Greek military junta, and the ensuing Turkish military invasion of the island, and hence the presence of Turkish soldiers, despite a legal reinstatement of a stable government. The desire of some of the ethnic Turkish people for the partition of the island of Cyprus through Taksim, the desire of some of the ethnic Greek people for the unification with Greece (Enosis), and mainland Turkish nationalists settling in as a show of force as a supposed means of protecting their people from what they considered to be the threat of Greek Cypriots also plays a role in the dispute.

Initially, with the occupation of the island by the British Empire from the Ottoman Empire in 1878 and subsequent annexation in 1914, the "Cyprus dispute" referred to general conflicts between Greek and Turkish islanders.[1][2]

However, the current international complications of the dispute stretch beyond the boundaries of the island itself and involve the guarantor powers under the Zürich and London Agreement (namely Greece, Turkey and the United Kingdom), the United Nations, and the European Union. The now-defunct Czechoslovakia and Eastern Bloc had previously interfered politically.[3]

The problem entered its current phase in the aftermath of the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus, occupying the northern third of Cyprus. Although the invasion was triggered by the 1974 Cypriot coup d'état, Turkish forces refused to depart after the legitimate government was restored. The Turkish Cypriot leadership later declared independence as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, although only Turkey has considered the move legal, and there continues to be broad international opposition to Northern Cyprus independence. According to the European Court of Human Rights, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus should be considered a puppet state under effective Turkish occupation, and legitimately belongs to Cyprus.[4][5][6] The United Nations Security Council Resolution 550 of 1984 calls for members of the United Nations to not recognize the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

As a result of the two communities and the guarantor countries committing themselves to finding a peaceful solution to the dispute, the United Nations maintains a buffer zone (known as the "Green Line") to avoid further intercommunal tensions and hostilities. This zone separates the southern areas of the Republic of Cyprus (predominantly inhabited by Greek Cypriots), from the northern areas (where Turkish Cypriots and Turkish settlers now reside). There was a warming of relations between Greek and Turkish Cypriots in the 2010s, with a renewal of talks officially beginning in early 2014. The Crans-Montana negotiations raised hopes for a long-term solution, but they ultimately stalled.[7][8] UN-led talks in 2021 similarly failed.[9]

Historical background before 1960

[edit]

The island of Cyprus was first inhabited in 9000 BC, with the arrival of farming societies who built round houses with floors of terrazzo. Cities were first built during the Bronze Age and the inhabitants had their own Eteocypriot language until around the 4th century BC.[10] The island was part of the Hittite Empire as part of the Ugarit Kingdom[11] during the late Bronze Age until the arrival of two waves of Greek settlement.

Cyprus experienced an uninterrupted Greek presence on the island dating from the arrival of Mycenaeans around 1400 BC, when the burials began to take the form of long dromos.[12] The Greek population of Cyprus survived through multiple conquerors, including Egyptian and Persian rule. In the 4th century BC, Cyprus was conquered by Alexander the Great and then ruled by the Ptolemaic Egypt until 58 BC, when it was incorporated into the Roman Empire. In the division of the Roman Empire around the 4th century AD, the island was assigned to the predominantly Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire.

Roman rule in Cyprus was interrupted in 649, when the Arab armies of the Umayyad Caliphate invaded the island. Fighting over the island between the Muslims and Romans continued for several years, until in 668 the belligerents agreed to make Cyprus a condominium. This arrangement persisted for nearly 300 years, until a Byzantine army conquered the island in around 965. Cyprus would become a theme of the Byzantine Empire until the late 12th century.

After an occupation by the Knights Templar and the rule of Isaac Komnenos, the island in 1192 came under the rule of the Lusignan family, who established the Kingdom of Cyprus. In February 1489 it was seized by the Republic of Venice.[citation needed] Between September 1570 and August 1571 it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire,[citation needed] starting three centuries of Turkish rule over Cyprus.

Starting in the early 19th century, ethnic Greeks of the island sought to bring about an end to almost 300 years of Ottoman rule and unite Cyprus with Greece. The United Kingdom took administrative control of the island in 1878, to prevent Ottoman possessions from falling under Russian control following the Cyprus Convention, which led to the call for union with Greece (enosis) to grow louder.[citation needed] Under the terms of the agreement reached between Britain and the Ottoman Empire,[citation needed] the island remained an Ottoman territory.

The Christian Greek-speaking majority of the island welcomed the arrival of the British,[citation needed] as a chance to voice their demands for union with Greece.

When the Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers, Britain renounced the Agreement, rejected all Turkish claims over Cyprus and declared the island a British colony. In 1915, Britain offered Cyprus to Constantine I of Greece on the condition that Greece join the war on the side of the British, which he declined.[13]

1918 to 1955

[edit]

Under British rule in the early 20th century, Cyprus escaped the conflicts and atrocities that went on elsewhere between Greeks and Turks during the Greco-Turkish War and the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Meanwhile, Turkish Cypriots consistently opposed the idea of union with Greece.

In 1925, Britain declared Cyprus a crown colony. In the years that followed, the determination of Greek Cypriots to achieve enosis continued. In 1931 this led to open revolt. A riot resulted in the death of six civilians, injuries to others and the burning of Britain's Government House in Nicosia. In the months that followed, about 2,000 people were convicted of crimes in connection with the struggle for union with Greece. Britain reacted by imposing harsh restrictions. Military reinforcements were dispatched to the island and the constitution suspended.[14][15] A special "epicourical" (reserve) police force was formed consisting of only Turkish Cypriots, press restrictions were instituted[16][17] and political parties were banned. Two bishops and eight other prominent citizens directly implicated in the conflict were exiled.[18] Municipal elections were suspended, and until 1943 all municipal officials were appointed by the government.[citation needed] The governor was to be assisted by an Executive Council, and two years later an Advisory Council was established; both councils consisted only of appointees and were restricted to advising on domestic matters only. In addition, the flying of Greek or Turkish flags or the public display of visages of Greek or Turkish heroes was forbidden.[citation needed]

The struggle for enosis was put on hold during World War II. In 1946, the British government announced plans to invite Cypriots to form a Consultative Assembly to discuss a new constitution. The British also allowed the return of the 1931 exiles.[19] Instead of reacting positively, as expected by the British, the Greek Cypriot military hierarchy reacted angrily because there had been no mention of enosis.[citation needed] The Cypriot Orthodox Church had expressed its disapproval, and Greek Cypriots declined the British invitation, stating that enosis was their sole political aim. The efforts by Greeks to bring about enosis now intensified, helped by active support of the Church of Cyprus, which was the main political voice of the Greek Cypriots at the time. However, it was not the only organisation claiming to speak for the Greek Cypriots. The Church's main opposition came from the Cypriot Communist Party (officially the Progressive Party of the Working People; Ανορθωτικό Κόμμα Εργαζόμενου Λαού; or AKEL), which also wholeheartedly supported the Greek national goal of enosis. However the British military forces and colonial administration in Cyprus did not see the pro-Soviet communist party as a viable partner.[citation needed]

During the 1940s, politically charged Turkish and Turkish-Cypriot newspaper reports, poems, and stories, including those by Dursun Cevlâni, contributed to a concerted effort to deny any Greek identity of the island and foster a political movement in support of a Turkish Cyprus.[20] By the mid-1950s, the "Cyprus is Turkish" party, movement, and slogan gained force in both Cyprus and Turkey.[20] In a 1954 editorial, Turkish Cypriot leader Dr. Fazil Kuchuk expressed the sentiment that the Turkish youth had grown up with the idea that "as soon as Great Britain leaves the island, it will be taken over by the Turks", and that "Turkey cannot tolerate otherwise".[21] By 1954 a number of Turkish mainland institutions were also active in the Cyprus issue such as the National Federation of Students, the Committee for the Defence of Turkish rights in Cyprus, the Welfare Organisation of Refugees from Thrace and the Cyprus Turkish Association.[citation needed] Above all, the Turkish trade unions were to prepare the right climate for the then main Turkish goal, the division of the island (taksim) into Greek and Turkish parts, thus keeping the British military presence and installations on the island intact. By this time a special Turkish Cypriot paramilitary organisation Turkish Resistance Organisation (TMT) was also established which was to act as a counterbalance to the Greek Cypriot enosis fighting organisation of EOKA.[22]

In 1950, Michael Mouskos, Bishop Makarios of Kition (Larnaca), was elevated to Archbishop Makarios III of Cyprus. In his inaugural speech, he vowed not to rest until union with "mother Greece" had been achieved.[citation needed] In Athens, enosis was a common topic of conversation, and a Cypriot native, Colonel George Grivas, was becoming known for his strong views on the subject. In anticipation of an armed struggle to achieve enosis, Grivas visited Cyprus in July 1951. He discussed his ideas with Makarios but was disappointed by the archbishop's contrasting opinion as he proposed a political struggle rather than an armed revolution against the British. From the beginning, and throughout their relationship, Grivas resented having to share leadership with the archbishop. Makarios, concerned about Grivas's extremism from their very first meeting, preferred to continue diplomatic efforts, particularly efforts to get the United Nations involved. The feelings of uneasiness that arose between them never dissipated. In the end, the two became enemies. In the meantime, on 16 August [Papagos Government] 1954, Greece's UN representative formally requested that self-determination for the people of Cyprus be applied.[23] Turkey rejected the idea of the union of Cyprus and Greece. Turkish Cypriot community opposed Greek Cypriot enosis movement, as under British rule the Turkish Cypriot minority status and identity were protected. Turkish Cypriot identification with Turkey had grown stronger in response to overt Greek nationalism of Greek Cypriots, and after 1954 the Turkish government had become increasingly involved. In the late summer and early autumn of 1954, the Cyprus problem intensified. On Cyprus the colonial government threatened publishers of seditious literature with up to two years imprisonment.[24] In December the UN General Assembly announced the decision "not to consider the problem further for the time being, because it does not appear appropriate to adopt a resolution on the question of Cyprus". Reaction to the setback at the UN was immediate and violent, resulting in the worst rioting in Cyprus since 1931.[citation needed]

EOKA campaign and creation of TMT, 1955–1959

[edit]

In January 1955, Grivas founded the National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston – EOKA). On 1 April 1955, EOKA opened an armed campaign against British rule in a coordinated series of attacks on police, military, and other government installations in Nicosia, Famagusta, Larnaca, and Limassol. This resulted in the deaths of 387 British servicemen and personnel[25] and some Greek Cypriots suspected of collaboration.[26] As a result of this a number of Greek Cypriots began to leave the police. This however did not affect the Colonial police force as they had already created the solely Turkish Cypriot (Epicourical) reserve force to fight EOKA paramilitaries. At the same time, it led to tensions between the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities. In 1957 the Turkish Resistance Organisation (Türk Mukavemet Teşkilatı TMT), which had already been formed to protect the Turkish Cypriots from EOKA, took action. In response to the growing demand for enosis, a number of Turkish Cypriots became convinced that the only way to protect their interests and identity of the Turkish Cypriot population in the event of enosis would be to divide the island – a policy known as taksim ("partition" in Turkish borrowed from Taqsīm (تقسیم) in Arabic) – into a Greek sector in the south and a Turkish sector in the north.

Establishment of the constitution

[edit]By now the island was on the verge of civil war. Several attempts to present a compromise settlement had failed. Therefore, beginning in December 1958, representatives of Greece and Turkey, the so-called "mother lands" opened discussions of the Cyprus issue. Participants for the first time discussed the concept of an independent Cyprus, i.e., neither enosis nor taksim. Subsequent talks always headed by the British yielded a so-called compromise agreement supporting independence, laying the foundations of the Republic of Cyprus. The scene then naturally shifted to London, where the Greek and Turkish representatives were joined by representatives of the Greek Cypriots, the Turkish Cypriots (represented by Arch. Makarios and Dr Fazıl Küçük with no significant decision-making power), and the British. The Zürich-London agreements that became the basis for the Cyprus constitution of 1960 were supplemented with three treaties – the Treaty of Establishment, the Treaty of Guarantee, and the Treaty of Alliance. The general tone of the agreements was one of keeping the British sovereign bases and military and monitoring facilities intact. Some Greek Cypriots, especially members of organisations such as EOKA, expressed disappointment because enosis had not been attained. In a similar way some Turkish Cypriots especially members of organisations such as TMT expressed their disappointment as they had to postpone their target for taksim, however most Cypriots that were not influenced by the three so called guarantor powers (Greece, Turkey, and Britain), welcomed the agreements and set aside their demand for enosis and taksim. According to the Treaty of Establishment, Britain retained sovereignty over 256 square kilometres, which became the Dhekelia Sovereign Base Area, to the northeast of Larnaca, and the Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area to the southwest of Limassol.

Cyprus achieved independence on 16 August 1960.

Independence, constitutional breakdown, and intercommunal talks, 1960–1974

[edit]According to constitutional arrangements, Cyprus was to become an independent, non-aligned republic with a Greek Cypriot president and a Turkish Cypriot vice-president. General executive authority was vested in a council of ministers with a ratio of seven Greeks to three Turks. (The Greek Cypriots represented 78% of the population and the Turkish Cypriots 18%. The remaining 4% was made up by the three minority communities: the Latins, Maronites and Armenians.) A House of Representatives of fifty members, also with a seven-to-three ratio, were to be separately elected by communal balloting on a universal suffrage basis. In addition, separate Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot Communal Chambers were provided to exercise control in matters of religion, culture, and education. According to Article 78(2) "any law imposing duties or taxes shall require a simple majority of the representatives elected by the Greek and Turkish communities respectively taking part in the vote". Legislation on other subjects was to take place by simple majority but again the President and the vice-president had the same right of veto—absolute on foreign affairs, defence and internal security, delaying on other matters—as in the Council of Ministers. The judicial system would be headed by a Supreme Constitutional Court, composed of one Greek Cypriot and one Turkish Cypriot and presided over by a contracted judge from a neutral country. The Constitution of Cyprus, while establishing an independent and sovereign republic, was, in the words of de Smith, an authority on Constitutional Law, "Unique in its tortuous complexity and in the multiplicity of the safeguards that it provides for the principal minority; the Constitution of Cyprus stands alone among the constitutions of the world".[27] Within a short period of time the first disputes started to arise between the two communities. Issues of contention included taxation and the creation of separate municipalities. Because of the legislative veto system, this resulted in a lockdown in communal and state politics in many cases.

Crisis of 1963–1964

[edit]Repeated attempts to solve the disputes failed. Eventually, on 30 November 1963, Makarios put forward to the three guarantors a thirteen-point proposal designed, in his view, to eliminate impediments to the functioning of the government. The thirteen points involved constitutional revisions, including the abandonment of the veto power by both the president and the vice-president. Turkey initially rejected it (although later in future discussed the proposal). A few days later, on Bloody Christmas, 21 December 1963, fighting erupted between the communities in Nicosia. In the days that followed it spread across the rest of the island, resulting in the death of 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots, and the forced displacement of 25,000 Turkish Cypriots. At the same time, the power-sharing government collapsed. How this happened is one of the most contentious issues in modern Cypriot history. The Greek Cypriots argue that the Turkish Cypriots withdrew to form their own administration. The Turkish Cypriots maintain that they were forced out. Many Turkish Cypriots chose to withdraw from the government. However, in many cases those who wished to stay in their jobs were prevented from doing so by the Greek Cypriots. Also, many of the Turkish Cypriots refused to attend because they feared for their lives after the recent violence that had erupted. There was even some pressure from the TMT as well. In any event, in the days that followed the fighting a frantic effort was made to calm tensions. In the end, on 27 December 1963, an interim peacekeeping force, the Joint Truce Force, was put together by Britain, Greece and Turkey. After the partnership government collapsed, the Greek Cypriot led administration was recognised as the legitimate government of the Republic of Cyprus at the stage of the debates in New York in February 1964.[28] The Joint Truce Force held the line until a United Nations peacekeeping force, UNFICYP, was formed following United Nations Security Council Resolution 186, passed on 4 March 1964.

Peacemaking efforts, 1964–1974

[edit]At the same time as it established a peacekeeping force, the Security Council also recommended that the Secretary-General, in consultation with the parties and the guarantor powers, designate a mediator to take charge of formal peacemaking efforts. U Thant, then the UN Secretary-General, appointed Sakari Tuomioja, a Finnish diplomat. While Tuomioja viewed the problem as essentially international in nature and saw enosis as the most logical course for a settlement, he rejected union on the grounds that it would be inappropriate for a UN official to propose a solution that would lead to the dissolution of a UN member state. The United States held a differing view. In early June, following another Turkish threat to intervene, Washington launched an independent initiative under Dean Acheson, a former Secretary of State. In July he presented a plan to unite Cyprus with Greece. In return for accepting this, Turkey would receive a sovereign military base on the island. The Turkish Cypriots would also be given minority rights, which would be overseen by a resident international commissioner. Makarios rejected the proposal, arguing that giving Turkey territory would be a limitation on enosis and would give Ankara too strong a say in the island's affairs. A second version of the plan was presented that offered Turkey a 50-year lease on a base. This offer was rejected by the Greek Cypriots and by Turkey. After several further attempts to reach an agreement, the United States was eventually forced to give up its effort.

Following the sudden death of Ambassador Tuomioja in August, Galo Plaza was appointed Mediator. He viewed the problem in communal terms. In March 1965 he presented a report criticising both sides for their lack of commitment to reaching a settlement. While he understood the Greek Cypriot aspiration of enosis, he believed that any attempt at union should be held in voluntary abeyance. Similarly, he considered that the Turkish Cypriots should refrain from demanding a federal solution to the problem. Although the Greek Cypriots eventually accepted the report, despite its opposition to immediate enosis, Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots rejected the plan, calling on Plaza to resign on the grounds that he had exceeded his mandate by advancing specific proposals. He was simply meant to broker an agreement. But the Greek Cypriots made it clear that if Galo Plaza resigned they would refuse to accept a replacement. U Thant was left with no choice but to abandon the mediation effort. Instead he decided to make his Good Offices available to the two sides via resolution 186 of 4 March 1964 and a Mediator was appointed. In his Report (S/6253, A/6017, 26 March 1965), the Mediator, now rejected by the Turkish Cypriot community, Dr Gala Plaza, criticized the 1960 legal framework, and proposed major amendments which were rejected by Turkey and Turkish Cypriots.

The end of the mediation effort was effectively confirmed when, at the end of the year, Plaza resigned and was not replaced.

In March 1966, a more modest attempt at peacemaking was initiated under the auspices of Carlos Bernades, the Secretary-General's Special Representative for Cyprus. Instead of trying to develop formal proposals for the parties to bargain over, he aimed to encourage the two sides agree to settlement through direct dialogue. However, ongoing political chaos in Greece prevented any substantive discussions from developing. The situation changed the following year.

On 21 April 1967, a coup d'état in Greece brought to power a military administration. Just months later, in November 1967, Cyprus witnessed its most severe bout of intercommunal fighting since 1964. Responding to a major attack on Turkish Cypriot villages in the south of the island, which left 27 dead, Turkey bombed Greek Cypriot forces and appeared to be readying itself for an intervention. Greece was forced to capitulate. Following international intervention, Greece agreed to recall General George Grivas, the Commander of the Greek Cypriot National Guard and former EOKA leader, and reduce its forces on the island.[29] Capitalising on the weakness of the Greek Cypriots, the Turkish Cypriots proclaimed their own provisional administration on 28 December 1967. Makarios immediately declared the new administration illegal. Nevertheless, a major change had occurred. The Archbishop, along with most other Greek Cypriots, began to accept that the Turkish Cypriots would have to have some degree of political autonomy. It was also realised that unification of Greece and Cyprus was unachievable under the prevailing circumstances.

In May 1968, intercommunal talks began between the two sides[30] under the auspices of the Good Offices of the UN Secretary-General. Unusually, the talks were not held between President Makarios and Vice-president Kucuk. Instead they were conducted by the presidents of the communal chambers, Glafcos Clerides and Rauf Denktaş. Again, little progress was made. During the first round of talks, which lasted until August 1968, the Turkish Cypriots were prepared to make several concessions regarding constitutional matters, but Makarios refused to grant them greater autonomy in return. The second round of talks, which focused on local government, was equally unsuccessful. In December 1969 a third round of discussion started. This time they focused on constitutional issues. Yet again there was little progress and when they ended in September 1970 the Secretary-General blamed both sides for the lack of movement. A fourth and final round of intercommunal talks also focused on constitutional issues, but again failed to make much headway before they were forced to a halt in 1974.

1974 Greek coup d'état and Turkish Intervention

[edit]The intercommunal strife was partly overshadowed by the division of the Greeks between the pro-independence Makarios, and the enosist National Front supported by the military junta of Greece. Grivas returned in 1971 and founded the EOKA-B, a militant enosist group, to oppose Makarios. Greece demanded Cyprus submit to its influence and the dismissal of the Cypriot foreign minister. Makarios survived an assassination attempt and retained enough popular support to remain in power. Enosist pressure continued to mount; although Grivas died suddenly in January 1974, a new junta had formed in Greece in September 1973.

In July 1974, the Cypriot National Guard launched a coup d'état that installed the pro-enosis Nikos Sampson as president. Makarios fled the country with British help. Faced with Greek control of the island, Turkey demanded that Greece dismiss Sampson, withdraw its armed forces, and respect Cyprus' independence; Greece refused. From the United States, envoy Joseph Sisco could not persuade Greece to accept Ecevit's Cyprus settlement which included Turkish-Cypriot control of a coastal region in the north and negotiations for a federal solution. The Soviet Union did not support enosis as it would strengthen NATO and weaken the left in Cyprus.

The Turkish invasion was driven by the assertive foreign policy of Bülent Ecevit, its prime minister, who was supported by his coalition partner Necmettin Erbakan. Turkey decided upon unilateral action after an invitation for joint action, made under the Treaty of Guarantee, was declined by Britain. On 20 July, Turkey invaded Cyprus with limited forces. The invasion achieved limited initial success, resulting in Greek forces occupying Turkish-Cypriot enclaves across the island. Within two days, Turkey secured a narrow corridor linking the northern coast with Nicosia, and on 23 July agreed to a cease-fire after securing a satisfactory bridgehead.

In Greece, the Turkish invasion caused political turmoil. On 23 July, the military junta collapsed and was replaced by Konstantinos Karamanlis's civilian government. On Cyprus the same day, Sampson was replaced by Acting President Glafcos Clerides in the absence of Makarios.

Formal peace talks convened two days later in Geneva, Switzerland, between Greece, Turkey and Britain. During the next five days, Turkey agreed to halt its advance on the condition that it would remain on the island until a political settlement was reached. Meanwhile, Turkish forces continued to advance as Greek forces occupied more Turkish-Cypriot enclaves. A new cease-fire line was agreed. On 30 July, the powers declared that the withdrawal of Turkish forces should be linked to a "just and lasting settlement acceptable to all parties concerned", with mentions of "two autonomous administrations – that of Greek-Cypriot community and that of the Turkish-Cypriot community".

Another round of talks was held on 8 August, this time including Cypriot representatives. Turkish Cypriots, supported by Turkey, demanded geographical separation from the Greek Cypriots; it was rejected by Makarios, who was committed to a unitary state. Deadlock ensued. On 14 August, Turkey demanded that Greece accept a Cypriot federal state, which would have resulted in the Turkish Cypriots - making up 18% of the population and 10% of land ownership – receiving 34% of the island. The talks ended when Turkey refused Clerides' request for 36 to 48 hours to consult the Cypriot and Greek governments. Within hours, Turkey launched a second offensive.[citation needed] Turkey controlled 36%[31] of the island by the time of the last ceasefire on 16 August 1974. The area between the combatants became a United Nations-administered buffer zone, or "green line".[32]

The Greek coup and Turkish invasion resulted in thousands of Cypriot casualties.[citation needed] The Government of Cyprus reported providing for 200,000 refugees.[33] 160,000[31] Greek Cypriots living in the Turkish-occupied northern region fled before Turkish forces or were evicted[citation needed]; they had made up 82% of the region's population. The United Nations approved the voluntary resettlement of the remaining 51,000 Turkish Cypriots in the south in the northern area; many had fled to the British areas and awaited permission to migrate to the Turkish-controlled area.

The divided island, 1974–1997

[edit]

At the second Geneva Conference beginning 9 August 1974, Turkey pressed for a federal solution to the problem against stiffening Greek resistance. While Turkish Cypriots wanted a bi-zonal federation, Turkey, under American advice, submitted a cantonal plan involving separation of Turkish-Cypriot areas from one another.[34] For security reasons Turkish-Cypriots did not favour cantons. Each plan embraced about thirty-four per cent of the territory.

These plans were presented to the conference on 13 August by the Turkish Foreign Minister, Turan Güneş. Clerides wanted thirty-six to forty-eight hours to consider the plans, but Güneş demanded an immediate response. This was regarded as unreasonable by the Greeks, the British, and the Americans, who were in close consultation.[35] Nevertheless, the next day, the Turkish forces extended their control to some 36 per cent of the island, afraid that delay would turn international opinion strongly against them.

Turkey's international reputation suffered as a result of the precipitous move of the Turkish military to extend control to a third of the island. The British prime minister regarded the Turkish ultimatum as unreasonable since it was presented without allowing adequate time for study. In Greek eyes, the Turkish proposals were submitted in the full awareness that the Greek side could not accept them, and reflected the Turkish desire for a military base in Cyprus. The Greek side went some way in their proposals by recognising Turkish 'groups' of villages and Turkish administrative 'areas'. But they stressed that the constitutional order of Cyprus should retain its bi-communal character based on the co-existence of the Greek and Turkish communities within the framework of a sovereign, independent and integral republic. Essentially the Turkish side's proposals were for geographic consolidation and separation and for a much larger measure of autonomy for that area, or those areas, than the Greek side could accept.

1975–1979

[edit]On 28 April 1975, Kurt Waldheim, the UN Secretary-General, launched a new mission of good offices. Starting in Vienna, over the course of the following ten months Clerides and Denktaş discussed a range of humanitarian issues relating to the events of the previous year. However, attempts to make progress on the substantive issues – such as territory and the nature of the central government – failed to produce any results. After five rounds, the talks fell apart in February 1976. In January 1977, the UN succeeded in organising a meeting in Nicosia between Makarios and Denktaş. This led to a major breakthrough. On 12 February, the two leaders signed a four-point agreement confirming that a future Cyprus settlement would be based on a federation. The size of the states would be determined by economic viability and land ownership. The central government would be given powers to ensure the unity of the state. Various other issues, such as freedom of settlement and freedom of movement, would be settled through discussion. Just months later, in August 1977, Makarios died. He was replaced by Spyros Kyprianou, the foreign minister.

In 1979 the ABC plan was presented by the US, as a proposal for a permanent solution of the Cyprus problem. It projected a Bicommunal Bizonal Federation with a strong central government. It was first rejected by the Greek Cypriot leader Spyros Kyprianou and later by Turkey.[36][37]

In May 1979, Waldheim visited Cyprus and secured a further ten-point set of proposals from the two sides. In addition to re-affirming the 1977 High-Level Agreement, the ten points also included provisions for the demilitarisation of the island and a commitment to refrain from destabilising activities and actions. Shortly afterwards a new round of discussions began in Nicosia. Again, they were short-lived. For a start, the Turkish Cypriots did not want to discuss Varosha, a resort quarter of Famagusta that had been vacated by Greek Cypriots when it was overrun by Turkish troops. This was a key issue for the Greek Cypriots. Second, the two sides failed to agree on the concept of 'bicommunalism'. The Turkish Cypriots believed that the Turkish Cypriot federal state would be exclusively Turkish Cypriot and the Greek Cypriot state would be exclusively Greek Cypriot. The Greek Cypriots believed that the two states should be predominantly, but not exclusively, made up of a particular community.

Turkish Cypriots' declaration of independence

[edit] |

|---|

| Constitution |

In May 1983, an effort by Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, then UN Secretary-General, foundered after the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the withdrawal of all occupation forces from Cyprus. The Turkish Cypriots were furious at the resolution, threatening to declare independence in retaliation. Despite this, in August, Pérez de Cuéllar gave the two sides a set of proposals for consideration that called for a rotating presidency, the establishment of a bicameral assembly along the same lines as previously suggested, and 60:40 representation in the central executive. In return for increased representation in the central government, the Turkish Cypriots would surrender 8–13 per cent of the land in their possession. Both Kyprianou and Denktaş accepted the proposals. However, on 15 November 1983, the Turkish Cypriots took advantage of the post-election political instability in Turkey and unilaterally declared independence. Within days the Security Council passed a resolution, no.541 (13–1 vote: only Pakistan opposed) making it clear that it would not accept the new state and that the decision disrupted efforts to reach a settlement. Denktaş denied this. In a letter informing the Secretary-General of the decision, he insisted that the move guaranteed that any future settlement would be truly federal in nature. Although the 'Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus' (TRNC) was soon recognised by Turkey, the rest of the international community condemned the move. The Security Council passed another resolution, no.550[38] (13–1 vote: again only Pakistan opposed) condemning the "purported exchange of ambassadors between Turkey and the Turkish Cypriot leadership".

The Restart of the Cyprus talks

[edit]In September 1984, talks resumed. After three rounds of discussions it was again agreed that Cyprus would become a bi-zonal, bi-communal, non-aligned federation. The Turkish Cypriots would retain 29 per cent for their federal state and all foreign troops would leave the island. In January 1985, the two leaders met for their first face-to-face talks since the 1979 agreement. However, while the general belief was that the meeting was being held to agree to a final settlement, Kyprianou insisted that it was a chance for further negotiations. The talks collapsed. In the aftermath, the Greek Cypriot leaders came in for heavy criticism, both at home and abroad. After that Denktaş announced that he would not make so many concessions again. Undeterred, in March 1986, de Cuéllar presented the two sides with a Draft Framework Agreement Archived 18 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Again, the plan envisaged the creation of an independent, non-aligned, bi-communal, bi-zonal state in Cyprus. However, the Greek Cypriots were unhappy with the proposals. They argued that the questions of removing Turkish forces from Cyprus was not addressed, nor was the repatriation of the increasing number of Turkish settlers on the island. Moreover, there were no guarantees that the full three freedoms would be respected. Finally, they saw the proposed state structure as being confederal in nature. Further efforts to produce an agreement failed as the two sides remained steadfastly attached to their positions.

The "Set of Ideas"

[edit]In August 1988, Pérez de Cuéllar called upon the two sides to meet with him in Geneva in August. There the two leaders – George Vasiliou and Rauf Denktaş – agreed to abandon the Draft Framework Agreement and return to the 1977 and 1979 High Level Agreements. However, the talks faltered when the Greek Cypriots announced their intention to apply for membership of the European Community (EC, subsequently EU), a move strongly opposed by the Turkish Cypriots and Turkey. Nevertheless, in June 1989, de Cuellar presented the two communities with the "Set of Ideas". Denktaş quickly rejected them as he not only opposed the provisions, he also argued that the UN Secretary-General had no right to present formal proposals to the two sides. The two sides met again, in New York, in February 1990. However, the talks were again short lived. This time Denktaş demanded that the Greek Cypriots recognise the existence of two peoples in Cyprus and the basic right of the Turkish Cypriots to self-determination.

On 4 July 1990, Cyprus formally applied to join the EC. The Turkish Cypriots and Turkey, which had applied for membership in 1987, were outraged. Denktaş claimed that Cyprus could only join the Community at the same time as Turkey and called off all talks with UN officials. Nevertheless, in September 1990, the EC member states unanimously agreed to refer the Cypriot application to the commission for formal consideration. In retaliation, Turkey and the TRNC signed a joint declaration abolishing passport controls and introducing a customs union just weeks later. Undeterred, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar continued his search for a solution throughout 1991. He made no progress. In his last report to the Security Council, presented in October 1991 under United Nations Security Council Resolution 716, he blamed the failure of the talks on Denktaş, noting the Turkish Cypriot leader's demand that the two communities should have equal sovereignty and a right to secession.

On 3 April 1992, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the new UN Secretary-General, presented the Security Council with the outline plan for the creation of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation that would prohibit any form of partition, secession or union with another state. While the Greek Cypriots accepted the Set of Ideas as a basis for negotiation, Denktaş again criticised the UN Secretary-General for exceeding his authority. When he did eventually return to the table, the Turkish Cypriot leader complained that the proposals failed to recognise his community. In November, Ghali brought the talks to a halt. He now decided to take a different approach and tried to encourage the two sides to show goodwill by accepting eight confidence building measures (CBMs). These included reducing military forces on the island, transferring Varosha to direct UN control, reducing restrictions on contacts between the two sides, undertaking an island-wide census and conducting feasibility studies regarding a solution. The Security Council endorsed the approach.

On 24 May 1993, the Secretary-General formally presented the two sides with his CBMs. Denktaş, while accepting some of the proposals, was not prepared to agree to the package as a whole. Meanwhile, on 30 June, the European Commission returned its opinion on the Cypriot application for membership. While the decision provided a ringing endorsement of the case for Cypriot membership, it refrained from opening the way for immediate negotiations. The Commission stated that it felt that the issue should be reconsidered in January 1995, taking into account "the positions adopted by each party in the talks". A few months later, in December 1993, Glafcos Clerides proposed the demilitarisation of Cyprus. Denktaş dismissed the idea, but the next month he announced that he would be willing to accept the CBMs in principle. Proximity talks started soon afterwards. In March 1994, the UN presented the two sides with a draft document outlining the proposed measures in greater detail. Clerides said that he would be willing to accept the document if Denktaş did, but the Turkish Cypriot leader refused on the grounds that it would upset the balance of forces on the island. Once again, Ghali had little choice but to pin the blame for another breakdown of talks on the Turkish Cypriot side. Denktas would be willing to accept mutually agreed changes, but Clerides refused to negotiate any further changes to the March proposals. Further proposals put forward by the Secretary-General in an attempt to break the deadlock were rejected by both sides.

Deadlock and legal battles, 1994–1997

[edit]At the Corfu European Council, held on 24–25 June 1994, the EU officially confirmed that Cyprus would be included in the Union's next phase of enlargement. Two weeks later, on 5 July, the European Court of Justice imposed restrictions on the export of goods from Northern Cyprus into the European Union. Soon afterwards, in December, relations between the EU and Turkey were further damaged when Greece blocked the final implementation of a customs union. As a result, talks remained completely blocked throughout 1995 and 1996.

In December 1996, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) delivered a landmark ruling that declared that Turkey was an occupying power in Cyprus. The case – Loizidou v. Turkey – centred on Titina Loizidou, a refugee from Kyrenia, who was judged to have been unlawfully denied the control of her property by Turkey. The case also had severe financial implications as the Court later ruled that Turkey should pay Mrs Loizidou US$825,000 in compensation for the loss of use of her property. Ankara rejected the ruling as politically motivated.

After twenty years of talks, a settlement seemed as far off as ever. However, the basic parameters of a settlement were by now internationally agreed. Cyprus would be a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation. A solution would also be expected to address the following issues:

- Constitutional framework

- Territorial adjustments

- Return of property to pre-1974 owners and/or compensation payments

- Return of displaced persons

- Demilitarisation of Cyprus

- Residency rights/repatriation of Turkish settlers

- Future peacekeeping arrangements

August 1996 incidents

[edit]In August 1996, Greek Cypriot refugees demonstrated with a motorcycle protest in Deryneia against the Turkish occupation of Cyprus. The ‘Motorcyclists March’ involved 2000 bikers from European countries and was organised by the Motorcyclists’ Federation of Cyprus.[39] The rally begun from Berlin to Kyrenia (a city in Occupied Cyprus) in commemoration of the twenty-second year of Cyprus as a divided country and aimed to cross the border using peaceful means.[39] The demonstrators' demand was the complete withdrawal of Turkish troops and the return of Cypriot refugees to their homes and properties. Among them was Tassos Isaac who was beaten to death.[40]

Another man, Solomos Solomou, was shot to death by Turkish troops while he was climbing to a flagpole to strike Turkish Flag during the same protests on 14 August 1996.[41] An investigation by authorities of the Republic of Cyprus followed, and the suspects were named as Kenan Akin and Erdan Emanet. International legal proceedings were instigated and arrest warrants for both were issued via Interpol.[42] During the demonstrations on 14 August 1996, two British soldiers were also shot by the Turkish forces: Neil Emery and Jeffrey Hudson, both from 39th Regiment Royal Artillery. Bombardier Emery was shot in his arm, whilst Gunner Hudson was shot in the leg by a high velocity rifle round and was airlifted to hospital in Nicosia then on to RAF Akrotiri.

Missile crisis

[edit]The situation took another turn for the worse at the start of 1997 when the Greek Cypriots announced that they intended to purchase the Russian-made S-300 anti-aircraft missile system.[43] Soon afterwards, the Cyprus Missile Crisis started.[44] The crisis effectively ended in December 1998 with the decision of the Cypriot government to transfer the S-300s to Crete, in exchange for alternative weapons from Greece.

EU accession and the settlement process, 1997–present

[edit]

In 1997 the basic parameters of the Cyprus Dispute changed. A decision by the European Union to open up accession negotiations with the Republic of Cyprus created a new catalyst for a settlement. Among those who supported the move, the argument was made that Turkey could not have a veto on Cypriot accession and that the negotiations would encourage all sides to be more moderate. However, opponents of the move argued that the decision would remove the incentive of the Greek Cypriots to reach a settlement. They would instead wait until they became a member and then use this strength to push for a settlement on their terms. In response to the decision, Rauf Denktaş announced that he would no longer accept federation as a basis for a settlement. In the future he would only be prepared to negotiate on the basis of a confederal solution. In December 1999 tensions between Turkey and the European Union eased somewhat after the EU decided to declare Turkey a candidate for EU membership, a decision taken at the Helsinki European Council. At the same time a new round of talks started in New York. These were short lived. By the following summer they had broken down. Tensions started to rise again as a showdown between Turkey and the European Union loomed over the island's accession.

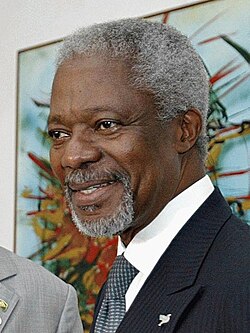

Perhaps realising the gravity of the situation, and in a move that took observers by surprise, Rauf Denktaş wrote to Glafcos Clerides on 8 November 2001 to propose a face-to-face meeting. The offer was accepted. Following several informal meetings between the two men in November and December 2001 a new peace process started under UN auspices on 14 January 2002. At the outset the stated aim of the two leaders was to try to reach an agreement by the start of June that year. However, the talks soon became deadlocked. In an attempt to break the impasse, Kofi Annan, the UN Secretary-General visited the island in May that year. Despite this no deal was reached. After a summer break Annan met with the two leaders again that autumn, first in Paris and then in New York. As a result of the continued failure to reach an agreement, the Security Council agreed that the Secretary-General should present the two sides with a blueprint settlement. This would form the basis of further negotiations. The original version of the UN peace plan was presented to the two sides by Annan on 11 November 2002. A little under a month later, and following modifications submitted by the two sides, it was revised (Annan II). It was hoped that this plan would be agreed by the two sides on the margins of the European Council, which was held in Copenhagen on 13 December. However, Rauf Denktaş, who was recuperating from major heart surgery, declined to attend. After Greece threatened to veto the entire enlargement process unless Cyprus was included in the first round of accession,[45] the EU was forced to confirm that Cyprus would join the EU on 1 May 2004, along with Malta and eight other states from Central and Eastern Europe.

Although it had been expected that talks would be unable to continue, discussions resumed in early January 2003. Thereafter, a further revision (Annan III) took place in February 2003, when Annan made a second visit to the island. During his stay he also called on the two sides to meet with him again the following month in The Hague, where he would expect their answer on whether they were prepared to put the plan to a referendum. While the Greek Cypriot side, which was now led by Tassos Papadopoulos, agreed to do so, albeit reluctantly, Rauf Denktaş refused to allow a popular vote. The peace talks collapsed. A month later, on 16 April 2003, Cyprus formally signed the EU Treaty of Accession at a ceremony in Athens.

Throughout the rest of the year there was no effort to restart talks. Instead, attention turned to the Turkish Cypriot elections, which were widely expected to see a victory by moderate pro-solution parties. In the end, the assembly was evenly split. A coalition administration was formed that brought together the pro-solution CTP and the Democrat Party, which had traditionally taken the line adopted by Rauf Denktaş. This opened the way for Turkey to press for new discussions. After a meeting between Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Kofi Annan in Switzerland, the leaders of the two sides were called to New York. There they agreed to start a new negotiation process based on two phases: phase one, which would just involve the Greek and Turkish Cypriots, being held on the island and phase two, which would also include Greece and Turkey, being held elsewhere. After a month of negotiations in Cyprus, the discussions duly moved to Burgenstock, Switzerland. The Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktaş rejected the plan outright and refused to attend these talks. Instead, his son Serdar Denktaş and Mehmet Ali Talat attended in his place. There a fourth version of the plan was presented. This was short-lived. After final adjustments, a fifth and final version of the Plan was presented to the two sides on 31 March 2004.

The UN plan for settlement (Annan Plan)

[edit]

Under the final proposals, the Republic of Cyprus would become the United Cyprus Republic. It would be a loose federation composed of two component states. The northern Turkish Cypriot constituent state would encompass about 28.5% of the island, the southern Greek Cypriot constituent state would be made up of the remaining 71.5%. Each part would have had its own parliament. There would also be a bicameral parliament on the federal level. In the Chamber of Deputies, the Turkish Cypriots would have 25% of the seats. (While no accurate figures are currently available, the split between the two communities at independence in 1960 was approximately 80:20 in favour of the Greek Cypriots.) The Senate would consist of equal parts of members of each ethnic group. Executive power would be vested in a presidential council. The chairmanship of this council would rotate between the communities. Each community would also have the right to veto all legislation.

One of the most controversial elements of the plan concerned property. During Turkey's military intervention/invasion in 1974, many Greek Cypriots (who owned 70% of the land and property in the north) were forced to abandon their homes. (Thousands of Turkish Cypriots were also forced to abandon their homes in the South.) Since then, the question of restitution of their property has been a central demand of the Greek Cypriot side. However, the Turkish Cypriots argue that the complete return of all Greek Cypriot properties to their original owners would be incompatible with the functioning of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federal settlement. To this extent, they have argued compensation should be offered. The Annan Plan attempted to bridge this divide. In certain areas, such as Morphou (Güzelyurt) and Famagusta (Gazimağusa), which would be returned to Greek Cypriot control, Greek Cypriot refugees would have received back all of their property according to a phased timetable. In other areas, such as Kyrenia (Girne) and the Karpass Peninsula, which would remain under Turkish Cypriot control, they would be given back a proportion of their land (usually one third assuming that it had not been extensively developed) and would receive compensation for the rest. All land and property (that was not used for worship) belonging to businesses and institutions, including the Church, the largest property owner on the island, would have been expropriated. While many Greek Cypriots found these provisions unacceptable in themselves, many others resented the fact that the Plan envisaged all compensation claims by a particular community to be met by their own side. This was seen as unfair as Turkey would not be required to contribute any funds towards the compensation.

Apart from the property issue, there were many other parts of the plan that sparked controversy. For example, the agreement envisaged the gradual reduction in the number of Greek and Turkish troops on the island. After six years, the number of soldiers from each country would be limited to 6,000. This would fall to 600 after 19 years. Thereafter, the aim would be to try to achieve full demilitarisation, a process that many hoped would be made possible by Turkish accession to the European Union. The agreement also kept in place the Treaty of Guarantee – an integral part of the 1960 constitution that gave Britain, Greece and Turkey a right to intervene militarily in the island's affairs. Many Greek Cypriots were concerned that the continuation of the right of intervention would give Turkey too large a say in the future of the island. However, most Turkish Cypriots felt that a continued Turkish military presence was necessary to ensure their security. Another element of the plan the Greek Cypriots objected to was that it allowed many Turkish citizens who had been brought to the island to remain. (The exact number of these Turkish 'settlers' is highly disputed. Some argue that the figure is as high as 150,000 or as low as 40,000. They are seen as settlers illegally brought to the island in contravention of international law. However, while many accepted Greek Cypriot concerns on this matter, there was a widespread feeling that it would be unrealistic – and legally and morally problematic – to forcibly remove every one of these settlers, especially as many of them had been born and raised on the island.)

Referendums, 24 April 2004

[edit]Under the terms of the plan, the Annan plan would only come into force if accepted by the two communities in simultaneous referendums. These were set for 24 April 2004. In the weeks that followed there was intense campaigning in both communities. However, and in spite of opposition from Rauf Denktaş, who had boycotted the talks in Switzerland, it soon became clear that the Turkish Cypriots would vote in favour of the agreement. Among Greek Cypriots opinion was heavily weighted against the plan. Tassos Papadopoulos, the president of Cyprus, in a speech delivered on 7 April called on Greek Cypriots to reject the plan. His position was supported by the centrist Diko party and the socialists of EDEK as well as other smaller parties. His major coalition partner AKEL, one of the largest parties on the island, chose to reject the plan bowing to the wishes of the majority of the party base. Support for the plan was voiced by Democratic Rally (DISY) leadership, the main right-wing party, despite opposition to the plan from the majority of party followers, and the United Democrats, a small centre-left party led by George Vasiliou, a former president. Glafcos Clerides, now retired from politics, also supported the plan. Prominent members of DISY who did not support the Annan plan split from the party and openly campaigned against it. The Greek Cypriot Church also opposed the plan in line with the views of the majority of public opinion.

The United Kingdom (a guarantor power) and the United States came out in favour of the plan. Turkey signalled its support for the plan. The Greek Government decided to remain neutral. However, Russia was troubled by an attempt by Britain and the US to introduce a resolution in the UN Security Council supporting the plan and used its veto to block the move. This was done because they believed that the resolution would provide external influence to the internal debate, which they did not view as fair.[46]

In 24 April referendum the Turkish Cypriots endorsed the plan by a margin of almost two to one. However, the Greek Cypriots resoundingly voted against the plan, by a margin of about three to one.

| Referendum result | Yes | No | Turnout | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | Total | % | ||

| Turkish Cypriot community | 50,500 | 64.90% | 14,700 | 35.09% | 87% |

| Greek Cypriot Community | 99,976 | 24.17% | 313,704 | 75.83% | 88% |

| Total legitimate ballots in all areas | 150,500 | 31.42% | 328,500 | 68.58% | |

The Cyprus dispute after the referendum

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (October 2016) |

In 2004, the Turkish Cypriot community was awarded "observer status" in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), as part of the Cypriot delegation. Since then, two Turkish Cypriot representatives of PACE have been elected in the Assembly of Northern Cyprus.[47][48]

On 1 May 2004, a week after the referendum, Cyprus joined the European Union. Under the terms of accession the whole island is considered to be a member of the European Union. However, the terms of the acquis communautaire, the EU's body of laws, have been suspended in Northern Cyprus.[49]

After the referendum, in June 2004, the Turkish Cypriot community, despite the objection of the Cypriot government, had its designation at the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, of which it has been an observer since 1979, changed to the "Turkish Cypriot State".[50]

Despite initial hopes that a new process to modify the rejected plan would start by autumn, most of the rest of 2004 was taken up with discussions over a proposal by the European Union to open up direct trade with the Turkish Cypriots and provide €259,000,000 in funds to help them upgrade their infrastructure. This provoked considerable debate. The Greek Cypriots stated that there can be no direct trade via ports and airports in Northern Cyprus as these are unrecognised and said that Turkish Cypriots should use Greek Cypriot facilities in the south are they are internationally recognised. This was rejected by the Turkish Cypriots as insincere and mocking by Papadopoulos and his government. At the same time, attention turned to the question of the start of Turkey's future membership of the European Union. At a European Council held on 17 December 2004, and despite earlier Greek Cypriot threats to impose a veto, Turkey was granted a start date for formal membership talks on condition that it signed a protocol extending the customs union to the new entrants to the EU, including Cyprus. Assuming this was done, formal membership talks would begin on 3 October 2005.

Following the defeat of the UN plan in the referendum there has been no attempt to restart negotiations between the two sides. While both sides have reaffirmed their commitment to continuing efforts to reach an agreement, the UN Secretary-General has not been willing to restart the process until he can be sure that any new negotiations will lead to a comprehensive settlement based on the plan he put forward in 2004. To this end, he asked the Greek Cypriots to present a written list of the changes they would like to see made to the agreement. This was rejected by President Tassos Papadopoulos on the grounds that no side should be expected to present their demands in advance of negotiations. However, it appears as though the Greek Cypriots would be prepared to present their concerns orally. Another Greek Cypriot concern centres on the procedural process for new talks. Mr. Papadopoulos said that he would not accept arbitration or timetables for discussions. The UN fears that this would lead to another open-ended process that could drag on indefinitely.

In October 2012, Northern Cyprus became an "observer member" country of the Economic Cooperation Organization under the name "Turkish Cypriot State".

According to Stratis Efthymiou, even though defeated, the referendum had a formative impact on the Greek Cypriot community;[51] Greek Cypriots felt that reunification is a touchable reality, and this undermined the nationalist struggle and ideas of military defence. According to Efthymiou, since the referendum, the phenomenon of draft dodging has become prevalent and the defence budget has turned into a trivial amount.[51]

Formula One and the Cyprus dispute

[edit]The podium display after the 2006 Turkish Grand Prix caused a controversy, when winner Felipe Massa received the trophy from Mehmet Ali Talat, who was referred to as the "President of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus". The government of the Republic of Cyprus filed an official complaint with the FIA. After investigating the incident, the FIA fined the organisers of the Grand Prix $5 million on 19 September 2006.[52] The Turkish Motorsports Federation (TOSFED) and the organisers of the Turkish Grand Prix (MSO) agreed to pay half the fined sum pending an appeal to be heard by the FIA International Court of Appeal on 7 November 2006.[53] TOSFED insisted the move was not planned and that Talat did fit FIA's criteria for podium presentations as a figure of world standing. It is likely that the FIA wanted to repair their impartiality in international politics, the FIA stood their ground forcing the appeal to be withdrawn.[54]

2008 elections in the Republic of Cyprus

[edit]

In the 2008 presidential elections, Papadopoulos was defeated by AKEL candidate Dimitris Christofias, who pledged to restart talks on reunification immediately.[55] Speaking on the election result, Mehmet Ali Talat stated that "this forthcoming period will be a period during which the Cyprus problem can be solved within a reasonable space of time – despite all difficulties – provided that there is will".[56] Christofias held his first meeting as president with the Turkish Cypriot leader on 21 March 2008 in the UN buffer zone in Nicosia.[57] At the meeting, the two leaders agreed to launch a new round of "substantive" talks on reunification, and to reopen Ledra Street, which has been cut in two since the intercommunal violence of the 1960s and has come to symbolise the island's division.[58] On 3 April 2008, after barriers had been removed, the Ledra Street crossing was reopened in the presence of Greek and Turkish Cypriot officials.[59]

2008–2012 negotiations and tripartite meetings

[edit]A first meeting of the technical committees was set to take place on 18 April 2008.[60] Talat and Christofias met socially at a cocktail party on 7 May 2008,[61] and agreed to meet regularly to review the progress of the talks so far.[62] A second formal summit was held on 23 May 2008 to review the progress made in the technical committees.[63] At a meeting on 1 July 2008, the two leaders agreed in principle on the concepts of a single citizenship and a single sovereignty,[64] and decided to start direct reunification talks very soon;[65] on the same date, former Australian foreign minister Alexander Downer was appointed as the new UN envoy for Cyprus.[66] Christofias and Talat agreed to meet again on 25 July 2008 for a final review of the preparatory work before the actual negotiations would start.[67] Christofias was expected to propose a rotating presidency for the united Cypriot state.[68] Talat stated he expected they would set a date to start the talks in September, and reiterated that he would not agree to abolishing the guarantor roles of Turkey and Greece,[69][70] with a reunification plan would be put to referendums in both communities after negotiations.[71]

In December 2008, the Athenian socialist daily newspaper To Vima described a "crisis" in relations between Christofias and Talat, with the Turkish Cypriots beginning to speak openly of a loose "confederation",[72][clarification needed] an idea strongly opposed by South Nicosia. Tensions were further exacerbated by Turkey's harassment of Cypriot vessels engaged in oil exploration in the island's Exclusive Economic Zone, and by the Turkish Cypriot leadership's alignment with Ankara's claim that Cyprus has no continental shelf.

On 29 April 2009, Talat stated that if the Court of Appeal of England and Wales (that will put the last point in Orams' case) makes a decision in the same spirit as the decision of European Court of Justice (ECJ) then the negotiation process in Cyprus will be damaged[73] in such a way that it will never be repaired once more.[74][full citation needed] The European Commission warned the Republic of Cyprus not to turn Orams' legal fight to keep their holiday home into a political battle over the divided island.[citation needed]

On 31 January 2010, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon arrived in Cyprus to accelerate talks aimed at reuniting the country.[75] The election of nationalist Derviş Eroğlu of the National Unity Party as president in Northern Cyprus on was expected to complicate reunification negotiations;[76] however, Eroǧlu stated that he was now also in favour of a federal state, a change from his previous positions.[77]

A series of five tripartite meetings took place from 2010 to 2012, with Ban, Christofias and Eroǧlu negotiating, but without any agreement on the main issues. When asked about the process in March 2011, Ban replied "The negotiations cannot be an open-ended process, nor can we afford interminable talks for the sake of talks".[78] That month saw the 100th negotiation since April 2008 without any agreement over the main issues- a deadlock that continued through the next year and a half despite a renewed push for Cyprus to unite and take over the EU presidency in 2012.[79]

Talks began to fall apart in 2012, with Ban Ki-moon stating that "there is not enough progress on core issues of reunification talks for calling an international conference".[80][full citation needed] Special Advisor of the Secretary-General Alexander Downer further commented that "If the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot Leaders cannot agree with each other on a model for a united Cyprus, then United Nations cannot make them".[81][full citation needed] Eroglu stated that joint committees with the Greek Cypriot side had been set up to take confidence-building measures in September that year, but negotiations were suspended in early 2013 because of a change of government in the Greek Cypriot community of Cyprus.[82][full citation needed] On 11 February 2014, Alexander Downer, UN Secretary-General's special adviser, stepped down.[83] The Greek and Turkish Cypriot leaders declared a Joint Communique.[7][84]

2014 renewed talks

[edit]

In February 2014, renewed negotiations to settle the Cyprus dispute began after several years of warm relations between the north and the south. On 11 February 2014, the leaders of Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities, Nicos Anastasiades and Derviş Eroğlu, respectively, revealed the following joint declaration:[85]

- The status quo is unacceptable and its prolongation will have negative consequences for the Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. The leaders affirmed that a settlement would have a positive impact on the entire region, while first and foremost benefiting Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots, respecting democratic principles, human rights and fundamental freedoms, as well as each other's distinct identity and integrity and ensuring their common future in a united Cyprus within the European Union.

- The leaders expressed their determination to resume structured negotiations in a results-oriented manner. All unresolved core issues will be on the table, and will be discussed interdependently. The leaders will aim to reach a settlement as soon as possible, and hold separate simultaneous referenda thereafter.

- The settlement will be based on a bi-communal, bi-zonal federation with political equality, as set out in the relevant Security Council Resolutions and the High Level Agreements. The united Cyprus, as a member of the United Nations and of the European Union, shall have a single international legal personality and a single sovereignty, which is defined as the sovereignty which is enjoyed by all member States of the United Nations under the UN Charter and which emanates equally from Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. There will be a single united Cyprus citizenship, regulated by federal law. All citizens of the united Cyprus shall also be citizens of either the Greek-Cypriot constituent state or the Turkish-Cypriot constituent state. This status shall be internal and shall complement, and not substitute in any way, the united Cyprus citizenship.

The powers of the federal government, and like matters that are clearly incidental to its specified powers, will be assigned by the constitution. The Federal constitution will also provide for the residual powers to be exercised by the constituent states. The constituent states will exercise fully and irrevocably all their powers, free from encroachment by the federal government. The federal laws will not encroach upon constituent state laws, within the constituent states' area of competences, and the constituent states' laws will not encroach upon the federal laws within the federal government's competences. Any dispute in respect thereof will be adjudicated finally by the Federal Supreme Court. Neither side may claim authority or jurisdiction over the other.

- The united Cyprus federation shall result from the settlement following the settlement's approval by separate simultaneous referenda. The Federal constitution shall prescribe that the united Cyprus federation shall be composed of two constituent states of equal status. The bi-zonal, bi-communal nature of the federation and the principles upon which the EU is founded will be safeguarded and respected throughout the island. The Federal constitution shall be the supreme law of the land and will be binding on all the federation's authorities and on the constituent states. Union in whole or in part with any other country or any form of partition or secession or any other unilateral change to the state of affairs will be prohibited.

- The negotiations are based on the principle that nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.

- The appointed representatives are fully empowered to discuss any issue at any time and should enjoy parallel access to all stakeholders and interested parties in the process, as needed. The leaders of the two communities will meet as often as needed. They retain the ultimate decision making power. Only an agreement freely reached by the leaders may be put to separate simultaneous referenda. Any kind of arbitration is excluded.

- The sides will seek to create a positive atmosphere to ensure the talks succeed. They commit to avoiding blame games or other negative public comments on the negotiations. They also commit to efforts to implement confidence building measures that will provide a dynamic impetus to the prospect for a united Cyprus.

The governments of both Greece and Turkey expressed their support for renewed peace talks.[86] The declaration was also welcomed by the European Union.[87]

On 13 February 2014, Archbishop Chrysostomos lent Anastasiades his backing on the Joint Declaration.[88]

On 14 February 2014, the Greek Cypriot negotiator Andreas Mavroyiannis and Turkish Cypriot negotiator Kudret Özersay held their first meeting and agreed to visit Greece and Turkey respectively.[89]

Reactions among the Greek Cypriot political parties were mixed. The opposition AKEL party declared its support for the declaration.[86] However, Nicolas Papadopoulos, the leader of DIKO, the main partner to Anastasiades' party DISY in the governing coalition, opposed the declaration, and DIKO's executive committee voted on 21 February to recommend to the party's central committee that the party withdraw from the coalition from 4 March.[90] On 27 February, DIKO decided to leave the coalition government, with the explanation that the Joint Declaration had conceded separate sovereignty to Turkish Cypriots.[91]

On 15 May 2015, in the first Akıncı–Anastasiades negotiation meeting, Northern Cyprus lifted visa requirements for Greek Cypriots, and Anastasiades presented maps of 28 minefields in the north, near the mountainous region of Pentadaktilos.[92]

2015–2017 talks

[edit]The President of the Republic of Cyprus, Nicos Anastasiades, and President of Northern Cyprus, Mustafa Akıncı, met for the first time and restarted peace talks on 12 May 2015. On 7 July 2017, the UN-sponsored talks which had been held in the Swiss Alps for the previous 10 days were brought to a halt after negotiations broke down.[93] Cyprus talks in Crans-Montana ended without a peace and reunification deal.[94]

On 1 October 2017, former British foreign secretary Jack Straw stated that only a partitioned island would bring the dispute between Turkish and Greek Cypriots to an end.[95] On 2 October, Turkish Cypriot FM Tahsin Ertugruloglu said federation on island is impossible.[96]

In late 2017, Business Monitor International, part of the Fitch Group, downgraded its assessment of a new Cyprus unification deal from slim to extremely remote.[97][98]

2018–2024 stalemate

[edit]In June 2018, in an attempt to jump-start the talks, UN Secretary-General António Guterres appointed Jane Holl Lute as his new adviser for Cyprus. Her mission was to consult the two Cypriot leaders, Nicos Anastasiades and Mustafa Akıncı, and the three guarantor parties (Greece, Turkey, and the United Kingdom) to determine if favourable conditions existed to resume UN-hosted negotiations and, if so, to prepare comprehensive "terms of reference". Lute conducted a first round of consultations in September 2018, a second in October 2018, a third in January 2019, and a fourth and final round on 7 April 2019, and found that both sides were seemingly farther apart.[99]

On 12 November 2018, the Dherynia checkpoint on the island's east coast and the Lefka-Aplikli checkpoint 52 km west of Nicosia were opened that brought the total crossing points to nine along the island's 180 km long buffer zone.[100]

On 5 February 2019, Greece and Turkey stated they wanted to defuse tensions between them through dialogue, including regarding the Cyprus dispute. Another dispute over oil and gas explorations in the waters of Cyprus' exclusive economic zone between the different parties is however keeping them from renewing talks.[101][102]

On 25 November 2019, Guterres, Anastasiades and Akıncı came together at an informal dinner in Berlin and discussed the next steps on the Cyprus issue. Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots could not however agree "terms of reference" to restart phased, meaningful, and results-oriented Cyprus negotiations.[103]

On 20 January 2020, the United Nations special envoy for Cyprus said that "there's growing scepticism as to whether reunification is still possible" as negotiations remained deadlocked.[104]

In February 2020, Mustafa Akıncı, the President of Northern Cyprus, said in an interview with The Guardian that if the reunification efforts in Cyprus failed then northern Cyprus would grow increasingly dependent on Turkey and could end up being swallowed up, as a de facto Turkish province, adding that the prospect of a Crimea-style annexation would be "horrible".[105] Turkish officials condemned him. Turkey's vice-president Fuat Oktay said: "I condemn the remarks that target Republic of Turkey which stands with TRNC in all conditions and protect its rights and interests." Communications Director Fahrettin Altun said that Akıncı does not deserve to be president, adding that many Turkish Cypriots and Turkish soldiers lost their lives (for Cyprus) and that Turkey has no designs on the soil of any country. Justice Minister Abdulhamit Gül criticised Akıncı's remarks, which he said hurt the ancestors and martyrs. In addition, Turkish Cypriot Prime Minister Ersin Tatar criticised Akıncı.[106]

No Cyprus unity talks breakthrough were seen in 2020. Nicos Rolandis (foreign minister of Cyprus 1978–1983 and commerce minister 1998–2003) said a political settlement to Cyprus dispute is almost impossible for now.[107] Prime Minister Ersin Tatar, who supports a two-state solution, won the 2020 Northern Cypriot presidential election.[108]

After the election of Ersin Tatar, both Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots insisted a two-state solution was the only option. Greece, Cyprus, the EU and the United Nations maintained a federation as the only solution which led to a freeze in talks after 2020.